What is Pseudomyxoma Peritonei

Pseudomyxoma peritonei also known as PMP is a very rare cancer that causes a buildup of jelly-like mucus or gelatinous deposits in your abdomen and pelvis (the peritoneal cavity), leading to symptoms like abdominal swelling, pain, and constipation 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14. Pseudomyxoma peritonei typically originates from a polyp (a small growth) in the appendix but can also start in other organs like your ovary, large intestine or from other abdominal tissues. Mucus-secreting cells may attach to the peritoneal lining and continue to secrete mucus. The majority of people with pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP) develop a “jelly belly” and need surgery to remove the tumors, often combined with chemotherapy called cytoreductive surgery (CRS) with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherap (HIPEC). However, your treatment depends on the size of the cancer and your general health. Your doctor might decide to closely monitor your cancer if it’s small, slow growing and you don’t currently need treatment. Pseudomyxoma peritonei is considered a rare condition, affecting 1 to 4 people per million each year 15, 16, 6. Pseudomyxoma peritonei incidence is higher in females, approximately 2 to 3 times that of males 17, 18, 19.

The name pseudomyxoma peritonei literally means “false mucinous tumor of the peritoneum”. Doctors call pseudomyxoma peritonei a false tumor because the cancer doesn’t form a tumor that can spread. Instead, pseudomyxoma peritonei usually starts as a cancerous polyp in your appendix. Pseudomyxoma peritonei commonly begins when a polyp in your appendix bursts, releasing mucin-producing cells into the peritoneum (the lining of your abdomen). When the polyp breaks through your appendix. It triggers a flood of mucin-producing cancer cells that, over time, affect your digestive system. That flood of jelly-like mucin is why some people call pseudomyxoma peritonei “jelly belly”.

Pseudomyxoma peritonei can also start in other organs like your ovary, large intestine or from other abdominal tissues.

Pseudomyxoma peritonei symptoms tend to be mild and may feel like common issues like constipation or indigestion. Sometimes,doctor detect pseudomyxoma peritonei early on while doing your annual exam or while checking for another medical condition. If you’re like most people, however, you’ll find out you have pseudomyxoma peritonei because your belly issues don’t go away or get worse.

In order to diagnose pseudomyxoma peritonei, your doctor will ask questions about your symptoms, like when you first noticed them or if they’re getting worse. Your doctor will do a physical examination and order blood tests and imaging tests to exclude other conditons.

Blood tests. Your doctor may order a complete blood count (CBC) and blood tests to look for tumor markers. Tumor markers are substances in your body that may indicate signs of cancer.

Imaging tests.

Your doctor may order the following imaging tests to look for issues like enlarged organs, fluid buildup in your abdomen (ascites) or mucin deposits in your belly (jelly belly): abdominal ultrasound, CT scan or MRI.

- Imaging tests. Imaging tests such as abdominal ultrasound, CT, MRI and PET scans. These scans help identify visible tumor spread, fluid buildup or organ involvement. However, imaging is often not sensitive enough to detect smaller cancers or early peritoneal disease.

- Biopsy of tissue from the peritoneum. A peritoneal biopsy is a procedure to remove a tissue sample from the peritoneum, the lining of your abdomen, for microscopic examination. It is used to diagnose conditions like peritoneal mesothelioma and can be performed using techniques such as a laparoscopy (keyhole surgery) or a CT-guided/ultrasound-guided core biopsy. The chosen method depends on your health, the location of the suspicious tissue, and the suitability for sampling.

- Peritoneal washing cytology. In this test, fluid from the abdominal cavity is surgically collected during a minor procedure. It’s then examined under a microscope. Doctors use peritoneal washing cytology to check for cancer cells floating in the peritoneal fluid. A medical pathologist will examine fluid or tissue cells under a microscope (cytology).

- Laparoscopy. Laparoscopy (keyhole surgery) is a safe, minimally invasive surgical procedure used to look directly inside your belly using a small camera. It allows your doctor to inspect the peritoneum, find hidden tumors, and take tissue or fluid samples for analysis.

- Tumor marker tests. Tumor marker tests use a sample of blood to look for chemicals made by cancer cells e.g. CEA, CA 199, CA 125.

Your treatment will depend on your situation, including your health. The main treatment for pseudomyxoma peritonei involves surgically removing as much of the tumor as possible, followed by chemotherapy delivered directly into your abdomen during the surgery called cytoreductive surgery (CRS) with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) 20, 21.

- Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) also known as debulking surgery: Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) is a surgical procedure to remove cancerous tumors from the abdomen and pelvic cavity that have spread to the peritoneum. Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) is often performed alongside heated intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC), where hot chemotherapy is circulated in the abdomen to kill any remaining microscopic cancer cells. The goal of cytoreductive surgery (CRS) is to completely remove all visible tumors, and the surgery may involve removing other affected organs as well.

- Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC): Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) is a two-stage cancer treatment for advanced abdominal cancers that combines surgery to remove tumors with the administration of heated chemotherapy drugs directly into your abdominal cavity. After visible tumors are surgically removed, a heated chemotherapy solution is circulated throughout your abdomen for a short period, typically 90 minutes to two hours to kill any remaining microscopic cancer cells, reducing the risk of recurrence.

Your surgeon will only do cytoreductive surgery (CRS) with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) if the surgery removes all or almost all of the cancerous tissue or mucin. Your surgeon will make that decision during your surgery.

Other types of surgery treat pseudomyxoma peritonei may include:

- Bowel resection if you have mucin in your small or large intestine

- Cholecystectomy to remove your gallbladder.

- Hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy to remove your fallopian tubes, ovaries and uterus.

- Liver capsulectomy to remove part of the surface of your liver.

- Omenectomy, which is removing the layer of fat that covers the front of your belly.

- Peritonectomy to remove your peritoneum. This is the membrane that lines the inside of your abdomen and pelvis.

- Splenectomy to remove your spleen.

Other treatments may include active surveillance, radiation therapy, systemic chemotherapy, or palliative care.

- Your doctor may recommend active surveillance if you have early or slow-growing pseudomyxoma peritonei and the risks of surgery outweigh the current risks of the disease. In active surveillance, your doctor will make regular checks on your overall health. Your doctor may do imaging tests and blood tests to see if pseudomyxoma peritonei is spreading.

- Palliative care. If you can’t have surgery, your doctor may recommend treatments like chemotherapy or radiation therapy that will slow down pseudomyxoma peritonei and ease your symptoms.

Doctor are investigating small bowel transplantation as treatment when you have pseudomyxoma peritonei in your small intestine.

Regular follow-up is necessary due to the risk of recurrence, even after successful treatment. In some cases, your doctor can treat and often cure pseudomyxoma peritonei. In some cases, surgery to remove all the cancer cells in your peritoneal cavity successfully controls pseudomyxoma peritonei for a long time 22, 23, 24. Other treatments may help you to live longer with it.

Figure 1. Pseudomyxoma peritonei

[Source 3 ]Figure 2. Pseudomyxoma peritonei umbilical nodule

[Source 8 ]Figure 3. Pseudomyxoma Peritonei CT

Footnotes: (A) Scattered accumulations on liver (arrows in A). (B) Sign of liver scalloping (red arrow in B) and deformation of spleen (arrows in B). (C) Omental cake: floccus soft tissue density masses diffused inside the greater omentum and shaped it like biscuits (arrows in C). (D) Massive mucus implanted in the abdominal cavity (arrows in D).

[Source 4 ]Figure 4. Pseudomyxoma Peritonei CT image

Footnotes: Typical computed tomography (CT) characteristics of pseudomyxoma peritonei. Computed tomography (CT) shows the following: (a) Enlargement of the appendiceal cavity and calcification of the appendiceal wall; (b) Abdominal girth enlargement caused by a large volume of intraperitoneal mucus deposits presenting as a “jelly belly”; (c) Thickened greater omentum presenting as an “omental cake”; (d) Small intestines compressed by mucus causing “central displacement”; (e) Scallop impression on the surface of the liver; (f) Contour deformation of the spleen

[Source 25 ]Figure 5. Pseudomyxoma peritonei pathological classification

Footnotes: Pathological classification of pseudomyxoma peritonei in the 2016 consensus of the Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International (PSOGI). (a, b) Acellular mucin, without identifiable tumor cells in the disseminated peritoneal mucinous deposits; (c, d) Low-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei, with tumor cells forming band-, island-, wave- or cluster-shaped tissue. Cancer cells present with a monolayer or pseudostratified arrangement, with slight nucleus atypia and rare mitotic figures; (e, f) High-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei, with a complex structure presenting band-, island-, gland-, cribriform-shaped tissue, abundant cellularity, and at least local regional severe atypia; (g, h) High-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei with signet ring cells, with abundant signet ring cells floating in the mucous pools. All sections were stained with H&E

[Source 25 ]What is the peritoneum and peritoneal cavity?

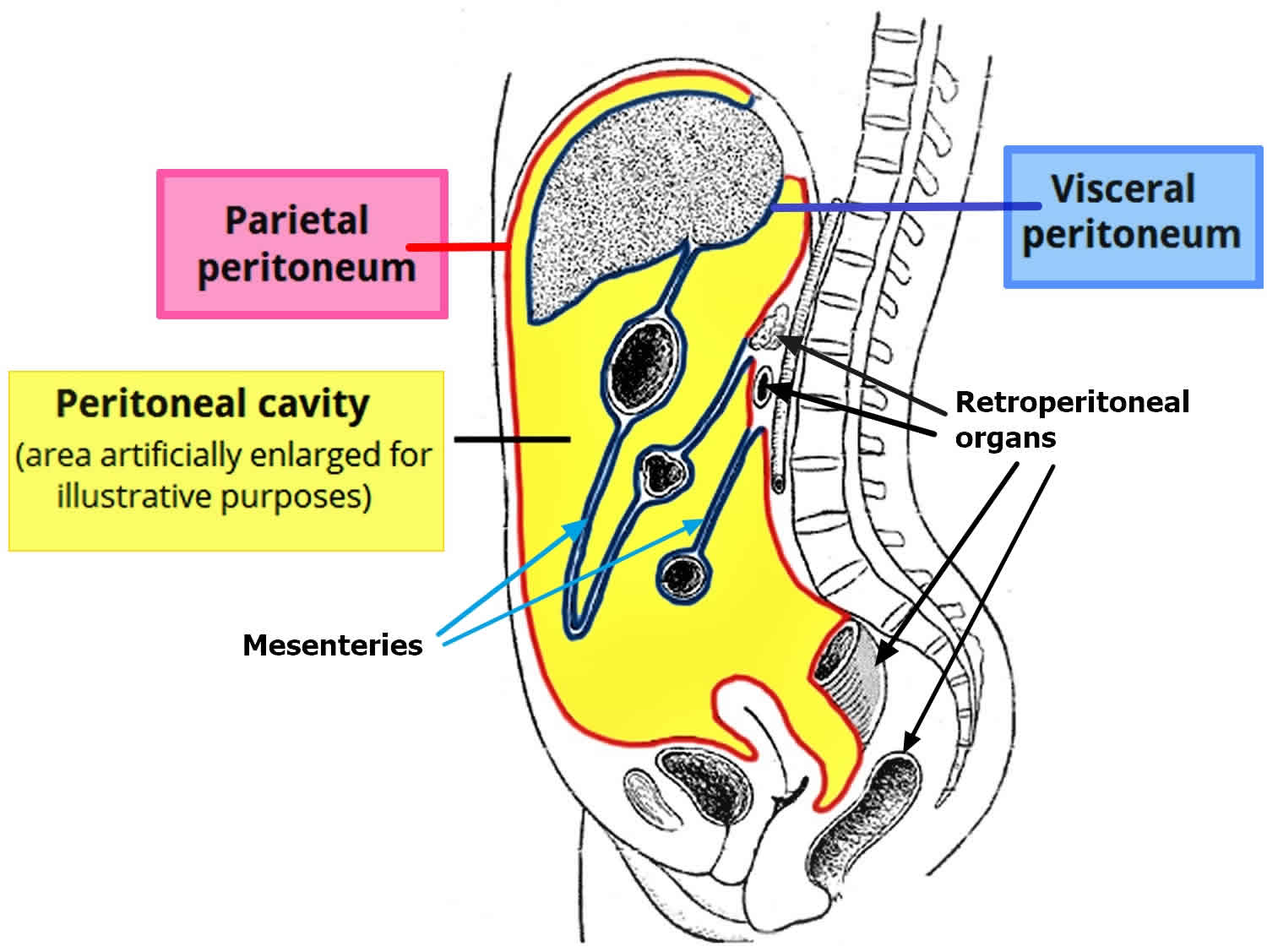

The peritoneum covers all of the organs within your tummy (abdomen), such as the bowel and the liver. The peritoneum protects the organs and acts as a barrier to infection. The peritoneum has 2 layers. One layer lines the abdominal wall and is called the parietal layer. The other layer covers the organs and is called the visceral layer.

There is a small amount of fluid between the two layers, which separates them and allows them to slide over each other. This fluid allows us to move around without causing any friction on the layers. This fluid also contains antibodies to fight infection.

The peritoneal cavity is the space within your tummy (abdomen) that is lined by the peritoneum. The peritoneal cavity contains folds of the peritoneum like the omentum (which hangs down from the stomach) and the mesentery (which supports the intestines). The peritoneal cavity normally contains a small amount of lubricating fluid and is the space where many abdominal organs, such as the liver, stomach, and intestines, are located. Organs located entirely or mostly within the cavity are called intraperitoneal organs, including the stomach, liver, spleen, and parts of the intestines. The peritoneal cavity’s function is to support and protect these organs, allow for their free movement, and provide an entry point for the immune system. The peritoneal cavity contains specialized immune cells, such as macrophages, that are part of the body’s defense system and play a role in tissue homeostasis.

When excess fluid accumulates in the peritoneal cavity, it is a condition known as ascites. The peritoneal cavity can become inflamed or infected, a condition known as peritonitis, often caused by a rupture of an abdominal organ.

Footnotes: Drawing of the peritoneal cavity illustrating the flow of peritoneal fluid (arrows) and frequent locations for peritoneal seeding (closed stars).

Abbreviations: L = liver; LS = lesser sac; S = spleen; TC = transverse mesocolon; PCL = phrenicocolic ligament; AC = ascending colon; DC = descending colon; SM = small bowel mesentery; SC = sigmoid mesocolon; R = rectum.

[Source 26 ]Figure 7. Mesentery anatomy

Footnotes: Anterior and sagittal sections of the abdominal cavity. The mesentery is a double fold of the peritoneum. There are true and specialized mesenteries. The true mesenteries connect to the posterior peritoneal wall. These are small bowel mesentery, transverse mesocolon and sigmoid mesentery (or mesosigmoid). The specialized mesenteries do not connect to the posterior peritoneal wall. These are greater omentum, lesser omentum and mesoappendix. The omentum is divided into the greater and lesser omentum. The greater omentum is subdivided into: gastrocolic ligament, gastrosplenic ligament and gastrophrenic ligament. The lesser omentum is subdivided into gastrohepatic ligament and hepatoduodenal ligament.

Pseudomyxoma peritonei causes

The cause of pseudomyxoma peritonei is unknown. Researchers know most pseudomyxoma peritonei starts with a mucinous tumor or polyp in your appendix that rupture, followed by massive colonization of tumor cells in the peritoneal cavity and continued production of mucus. Cases of pseudomyxoma peritonei caused by mucinous tumors originating from organs such as the ovaries, colon, pancreas, and urachus have also been reported 27, 28, 29, 30. Patients with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) demonstrate an increased risk of developing mucinous adenocarcinoma of the appendix. KRAS mutation has also been present in 70 % of appendiceal adenomas 31. Pseudomyxoma peritonei is more common in women than men. In women, this type of cancer can sometimes be confused with ovarian cancer. Ovarian cancer may also cause a swollen abdomen. Some types of ovarian cancer cells also produce mucin.

The main feature of pseudomyxoma peritonei is the extensive dissemination of copious mucus-containing tumor cells in the abdominal cavity. Mucus accumulation causes progressive abdominal distention, intestinal obstruction, malnutrition, cachexia, and ultimately death.

Pseudomyxoma peritonei pathological classification criteria and diagnostic terminology are confusing because there are multiple classification systems in the world (Table 1). This confusion is indicative of the diverse clinical manifestations, variable pathological characteristics, and elusive features of pseudomyxoma peritonei. The commonly used pathological classification methods in the literature include the Ronnett three-tier system 32, the Bradley two-tier system 33, and the WHO two-tier system 34. The simultaneous use of different classification systems may have the following disadvantages: (1) the research results of different centers are heterogeneous and are thus not conducive to the comparison of identical or similar studies; (2) as a rare disease, it is not conducive to the organization of relatively scarce research resources for collaborative studies; (3) Ronnett’s three-tier system includes non-appendiceal pseudomyxoma peritonei; and (4) both the Bradley and WHO systems leave out the classification of signet ring cells.

At the 12th International Conference on Peritoneal Carcinoma in Berlin in 2012, experts had heated discussions on pseudomyxoma peritonei pathological classification and diagnostic terminology. It was not until 2016 that a written consensus by the Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International (PSOGI) on pseudomyxoma peritonei pathology classification and diagnostic terminology was published 35. Currently, the 2016 Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International (PSOGI) classification system is widely recognized by peritoneal carcinomatosis experts around the world.

According to the Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International (PSOGI) consensus, pseudomyxoma peritonei is divided into 4 categories:

- Acellular mucin;

- Low-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei (LMCP) or disseminated peritoneal adenomucinosis (DPAM);

- High-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei (HMCP) or peritoneal mucinous carcinomatosis (PMCA); and

- High-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei with signet ring cells (HMCP-S) or peritoneal mucinous carcinomatosis with signet ring cells (PMCA⁃S).

It should be noted that DPAM and PMCA are synonyms for LMCP and HMCP, respectively, which are no longer recommended as standard pathological terminology 36.

Table 1. Histologic Classifications of Pseudomyxoma Peritonei

| Classification | Description | |

| Oscar Polano 1921 37 | The cystadenoma mucinosum peritonei simplex | Superficial implantation on the peritoneum |

| The cystadenoma malignum pseudomucinosum peritonei | Aggressive and destructive features with malignant performance of penetrating abdominal cavity in greater size, spreading to more sites and even perforating the intestines | |

| Ronnett et al 32 | Disseminated peritoneal adenomucinosis (DPAM) | DPAM comprised peritoneal lesions composed of numerous extracellular mucin-containing scant simple to focally proliferative mucinous epithelium with minimal-to-moderate cytologic atypia and inapparent mitotic activity, with or without an associated appendiceal mucinous adenoma |

| Peritoneal mucinous carcinomatosis (PMCA) | Peritoneal lesions that accord with morphologic and cytologic characteristics of carcinoma as more abundant epithelium proliferate in glands, nests, or individual cells, with or without an associated primary mucinous adenocarcinoma | |

| Hybrid tumors | Peritoneal mucinous adenocarcinoma with intermediate features | |

| Bradley et al 33 | Low-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei (MCP-L) | Cases have a significant adenoma-like or well-differentiated component and should lack a poorly differentiated component including Signet ring cells |

| High-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei (MCP-H) | Cases with moderately or any poorly differentiated component, that includes all cases with a well-developed signet-ring cell component | |

| AJCC and WHO 2010 38 | Low-grade pseudomyxoma peritonei | Mucin pools with low cellularity (<10%), bland cytology and nonstratified cuboidal epithelium |

| High-grade pseudomyxoma peritonei | Mucin pools with high cellularity, moderate/severe cytologic atypia and cribriform/signet ring morphology with desmoplastic stroma | |

| Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International (PSOGI) 2016 35 | Acellular mucin (AC) | Mucin without epithelial cells |

| Low-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei/disseminated peritoneal adenomucinosis (DPAM) | Pseudomyxoma peritonei with low-grade histologic features | |

| High-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei/peritoneal mucinous carcinomatosis (PMCA) | Pseudomyxoma peritonei with high-grade histologic features | |

| High-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei with signet ring cells/Peritoneal mucinous carcinomatosis with signet ring cells (PMCA-S) | Pseudomyxoma peritonei with signet ring cells |

Abbreviations: PMP = pseudomyxoma peritonei; PSOGI = Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International; AJCC = American Joint Committee on Cancer; WHO = World Health Organization.

[Source 4 ]Table 2. Pathological classification and terminology of the pseudomyxoma peritonei

| 2016 Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International (PSOGI) classification | Counterparts | |

|---|---|---|

| 2017 American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system, 8th edition (TNM) | 2019 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of tumors, 5th edition | |

| Acellular mucin: (1) Mucin without neoplastic epithelium; (2) Confined to or distant from organ surface | M1a | pM1a |

| Low-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei (LMCP): (1) Low-grade cytology; (2) Rare mitosis; (3) Few tumoral mucinous epithelium (< 20% of tumor volume) | M1b. G1, well-differentiated | pM1b, Grade 1: (1) Hypocellular mucinous deposits; (2) Neoplastic epithelial elements have low-grade cytology; (3) No infiltrative-type invasion |

| High-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei (HMCP): Features of one or more of the following (At least focally): (1) high-grade cytology; (2) Infiltration of adjacent tissues; (3) Invasion of vascular lymphatic vessels or surrounding nerves; (4) Cribriform growth; (5) Neoplastic mucinous epithelium (> 20% of tumor volume); Sub-classification based on differentiation (1) well-differentiated: Mainly composed of single- tubular glands; Tumor cell polarity exists; Obvious tumor cell atypia; Infiltrative components; (2) Moderately-differentiated: Solid sheet tumor cells mixed with adenoid structures; Minimal or no polarity; (3) Poorly-differentiated: Highly irregular to no adenoid differentiation Cell polarity disappears | M1b. G2 or G3, moderately- or poorly-differentiated | pM1b, Grade 2: (1) Hypercellular mucinous deposits as judged at 20 × magnification; (2) High-grade cytological features; (3) Infiltrative-type invasion characterized by jagged or angulated glands in a desmoplastic stroma, or a small mucin pool pattern with numerous mucin pools containing clusters of tumor cells |

| High-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei with signet ring cells (HMCP-S): Tumor with signet ring cell component (signet ring cells ≥ 10%) | M1b. G3, poorly- differentiated; PMCA-S (peritoneal mucinous carcinomatosis with signet ring cells) | pM1b, Mucinous tumor deposits with signet-ring cells |

Abbreviations: PMP = pseudomyxoma peritonei; PSOGI = Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International; AJCC = American Joint Committee on Cancer. AM = acellular mucin; LMCP = low-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei; HMCP = high-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei; HMCP-S = high-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei with signet ring cells; DPAM, disseminated peritoneal adenomucinosis; PMCA-I, peritoneal mucinous carcinomatosis with intermediate feature; PMCA, peritoneal mucinous carcinomatosis; NA, not applicable

[Source 25 ]How does pseudomyxoma peritonei spread?

Pseudomyxoma peritonei doesn’t act like most cancers. It rarely spreads through the bloodstream or the lymphatic system to any other part of the body. Instead, it spreads inside your abdomen. The cancer cells generally spread by following the peritoneal fluid flow. They attach to the peritoneum at particular sites. Here they produce mucus which collects inside the abdomen and eventually causes symptoms. Without treatment, it will take over the peritoneal cavity. It can press on the bowel and other organs.

Pseudomyxoma peritonei develops very slowly. It might be years before you have any symptoms of this type of cancer. Because of this, it has usually spread beyond the appendix before diagnosis.

Pseudomyxoma peritonei signs and symptoms

Pseudomyxoma peritonei symptoms develop slowly and you may not notice them or assume your symptoms are from a common illness. Some people won’t have any symptoms of pseudomyxoma peritonei.

Pseudomyxoma peritonei symptoms may include:

- Swollen abdomen (abdominal distension). This is when your abdomen is noticeably swollen.

- Abdominal pain. This may feel like general discomfort or pain as mucin builds up in your belly.

- Constipation. Abdominal swelling may block your large intestine so you can’t pass poop.

- Difficulty getting pregnant. Pressure from mucin buildup or inflammation in your reproductive organs can make it difficult to conceive, especially for women.

- Hernias. Mucin buildup may push one of your organs through a gap in your muscle wall. Inguinal hernia is one of the most common pseudomyxoma peritonei signs in men.

- Loss of appetite.

- Feeling of fullness.

- Changes in bowel habits.

- Nausea.

Often, doctors can only diagnose pseudomyxoma peritonei properly after an operation to look into the abdomen. This operation is called a laparotomy.

Pseudomyxoma peritonei diagnosis

Pseudomyxoma peritonei symptoms tend to be mild and may feel like common issues like constipation or indigestion. Sometimes,doctor detect pseudomyxoma peritonei early on while doing your annual exam or while checking for another medical condition. If you’re like most people, however, you’ll find out you have pseudomyxoma peritonei because your belly issues don’t go away or get worse.

In order to diagnose pseudomyxoma peritonei, your doctor will ask questions about your symptoms, like when you first noticed them or if they’re getting worse. Your doctor will do a physical examination and order blood tests and imaging tests to exclude other conditons.

Blood tests. Your doctor may order a complete blood count (CBC) and blood tests to look for tumor markers. Tumor markers are substances in your body that may indicate signs of cancer.

Imaging tests.

Your doctor may order the following imaging tests to look for issues like enlarged organs, fluid buildup in your abdomen (ascites) or mucin deposits in your belly (jelly belly): abdominal ultrasound, CT scan or MRI.

Pseudomyxoma peritonei diagnosis may include:

- Imaging tests. Imaging tests such as CT, MRI and PET scans are typically the first step in looking for suspected peritoneal carcinomatosis. These scans help identify visible tumor spread, fluid buildup or organ involvement. However, imaging is often not sensitive enough to detect smaller cancers or early peritoneal disease. Therefore, a negative scan does not rule out peritoneal carcinomatosis.

- Biopsy of tissue from the peritoneum. A peritoneal biopsy is a procedure to remove a tissue sample from the peritoneum, the lining of your abdomen, for microscopic examination. It is used to diagnose conditions like peritoneal mesothelioma and can be performed using techniques such as a laparoscopy (keyhole surgery) or a CT-guided/ultrasound-guided core biopsy. The chosen method depends on your health, the location of the suspicious tissue, and the suitability for sampling.

- Peritoneal washing cytology. In this test, fluid from the abdominal cavity is surgically collected during a minor procedure. It’s then examined under a microscope. Doctors use peritoneal washing cytology to check for cancer cells floating in the peritoneal fluid. Even when no visible cancer is present, a positive cytology result is a strong sign that peritoneal spread has happened.

- Laparoscopy. Laparoscopic exploration (keyhole surgery) is a safe, minimally invasive surgical procedure used to look directly inside the abdominal cavity using a small camera. It allows your doctor to inspect the peritoneum, find hidden tumors, and take tissue or fluid samples. This test is especially valuable for finding peritoneal metastases that are too small to be seen with imaging.

- Tumor marker tests. Tumor marker tests use a sample of blood to look for chemicals made by cancer cells e.g. CEA, CA 199, CA 125.

- Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA). This is a newer blood test that looks for small pieces of DNA from cancer cells in the blood. It can help find peritoneal cancer that doesn’t show up on scans. However, the role of ctDNA in diagnosis is still uncertain.

Sometimes metastatic cancer to the peritoneum is diagnosed during surgery for another issue or for another abdominal cancer.

A consensus on the preoperative evaluation for pseudomyxoma peritonei was reached in the 2008 PSOGI Consensus, which greatly facilitated patient diagnosis and selection, mainly including 4 aspects 39.

- Serum tumor markers, which mainly combined testing of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), carbohydrate antigen 125 (CA125), and carbohydrate antigen 199 (CA199). CEA, CA125, and CA199 are helpful indicators for evaluating the degree of tumor invasion, ascites production and tumor burden, and the proliferation of cancer cells, respectively.

- A computed tomography (CT) examination + 3D reconstruction is the optimal choice for routine preoperative examination. Typically, CT scan of pseudomyxoma peritonei revealed a right lower abdominal cystic or cystic-solid mass frequently with calcification; copious mucinous ascites in the abdominal cavity; extensive organ invasion or compression;

- Laparoscopic exploration and exfoliative cytology are both optional.

Imaging Studies

Several imaging studies may be utilized to evaluate patients with suspected or known peritoneal carcinomatosis 40. Although regular CT has been chosen as the preferred technique in the follow-up, omitting recurrence could happen when both peritoneum and omentum resections have been done and tumor infiltration comes along the small bowel 41. It is appropriate for low-grade pseudomyxoma peritonei patients to get annual CT scan of abdomen and pelvis in the first 6 years, chest examination and the frequency should be added if meets high-grade lesion 42. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) owns particular advantages in high sensitivity of the assessment of pseudomyxoma peritonei, as gelatinous implants that consist of plenty of water molecules show high signal intensity on T2-weighted images 43. It is deemed a normal phenomenon if peritoneal enhancement is equivalent to muscle enhancement 44. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides tough evidence of metastasis in the liver and perihepatic region for its favorable soft tissue contrast which is related to poor prognosis 41.

Computed tomography (CT)

A contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis is the primary imaging modality for evaluating patients with suspected or known peritoneal carcinomatosis 45. A contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis provides detailed anatomic information, suggesting tumor deposits along the peritoneal reflections, the greater and lesser omenta, mesentery, and serosal surfaces of abdominal organs. Features that raise suspicion for peritoneal carcinomatosis include soft-tissue nodules on the peritoneal surfaces, focal or diffuse peritoneal thickening, omental caking, and ascites. CT can also help identify mucinous components by revealing low-attenuation masses, characteristic of pseudomyxoma peritonei (see Image. Pseudomyxoma Peritonei) secondary to appendiceal or ovarian neoplasms. However, sensitivity may be limited for detecting smaller lesions (<5 mm), and the disease burden in the small bowel or mesentery is frequently underestimated due to overlapping loops of bowel and variable bowel distension 46.

Several radiologic signs can predict a high likelihood of nonresectability, eg, a large solitary mass in the upper abdomen (often >5 cm), diffuse small bowel wall thickening, or the “smudge” sign where small bowel loops appear matted together, findings sometimes referred to collectively as “Sugarbaker’s Criteria” or the Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI). Although CT is routinely used to approximate the Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI), studies suggest it can either underestimate or overestimate the true extent of disease by up to 20% to 30% 47.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) plays an increasingly vital role in evaluating peritoneal carcinomatosis, offering superior soft-tissue contrast and multi-planar capabilities without the risks associated with ionizing radiation. In particular, diffusion-weighted imaging enhances the detection of small peritoneal deposits and mucinous lesions, which are critical for assessing conditions, such as pseudomyxoma peritonei. When combined with contrast-enhanced sequences, MRI further refines staging by clearly delineating the extent of disease, a key factor in planning cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy 48.

Recent studies have demonstrated that MRI can achieve sensitivity values of approximately 90% to 95% and specificity values of around 85% to 92% for detecting peritoneal metastases, particularly for lesions larger than 5 mm 49.

Positron emission tomography (PET)

Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET), typically combined with computed tomography (PET/CT), can reveal hypermetabolic foci within peritoneal surface cancers and detect extraperitoneal metastases that may alter therapeutic decision-making. Its sensitivity, however, is limited in low-cellularity mucinous neoplasms, including pseudomyxoma peritonei, where radiotracer uptake can be insufficient for accurate detection. Moreover, inflammatory changes or surgical manipulation can yield false-positive signals. Therefore, PET/CT is generally regarded as an adjunct to contrast-enhanced CT or MRI, most valuable for ruling out distant metastatic disease or clarifying ambiguous findings rather than serving as the principal staging modality 50, 51.

Diagnostic Laparoscopy

Diagnostic laparoscopy provides the most accurate assessment of peritoneal disease burden and distribution, while also allowing for the collection of biopsies 52. A diagnostic laparoscopy is a “keyhole” surgery that uses a thin, lighted camera to examine the abdominal and pelvic organs when other tests are inconclusive. A surgeon makes a small incision, often near the belly button, to insert the laparoscope and inflatable gas to get a clear view. Diagnostic laparoscopy should be performed in all patients for whom cytoreduction and intraperitoneal chemotherapy are considered, and is often also performed in cases where imaging is unclear 52. By permitting real-time assessment of tumor distribution and burden, particularly in areas prone to underestimation on CT or MRI, laparoscopy enables a more precise estimation of the Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) and aids in evaluating resectability (see Figure 8. Peritoneal Cancer Index below) 53, 54, 55.

Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) is a standardized quantitative tool for estimating the extent and distribution of peritoneal carcinomatosis. It partitions the abdominal cavity into 13 discrete anatomical regions (0 through 12) and assigns each region a lesion size (LS) score ranging from 0 to 3. The Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) is then calculated by summing the lesion size scores across all areas, with a maximum possible value of 39 reflecting extensive disease. Notably, lesion size 3 (>5 cm or confluence of disease) is associated with a poor prognosis 56, 57.

In clinical practice, the Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) is a robust surrogate for tumor burden, correlates strongly with both resectability and survival outcomes, and often dictates eligibility for cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC). While radiologic estimates of the PCI using CT or MRI can guide patient selection for surgery, definitive scoring typically occurs intraoperatively via either laparotomy or, in selected centers, laparoscopic exploration. Accurate scoring is paramount, as patients with a PCI exceeding a certain threshold—commonly 20 for high-grade appendiceal or colorectal cancer, for example—are more likely to have incomplete cytoreduction and diminished survival benefits from aggressive surgical intervention. Consequently, the Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) is integral to risk stratification, surgical planning, and counseling regarding prognosis in the interprofessional management of peritoneal carcinomatosis 56.

Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI)

The Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) is a numerical score used to quantify the extent of cancer spread throughout the abdomen and pelvis 56, 57. The Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) is determined during surgery by dividing the abdomen into 13 regions, scoring each from 0 to 3 based on tumor size, and summing the scores for a total Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) value 58, 59, 60. A lower Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) indicates less extensive disease and is associated with a better prognosis and a higher likelihood of successful complete cytoreductive surgery, while a higher Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) suggests more widespread disease.

How Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) is calculated 59, 60, 61:

- The abdomen and pelvis are divided into 13 regions:

- 0. Central.

- 1. Right upper.

- 2. Epigastrium.

- 3. Left upper.

- 4. Left flank.

- 5. Left lower.

- 6. Pelvis.

- 7. Right lower.

- 8. Right flank.

- 9. Upper jejunum.

- 10. Lower jejunum.

- 11. Upper ileum.

- 12. Lower ileum.

- Each region is assigned a score from 0 to 3, based on the size of the largest tumor in that region:

- 0: No tumor

- 1: Tumor implants up to 0.5 cm

- 2: Tumor implants between 0.5 cm and 5 cm

- 3: Tumor implants larger than 5 cm or clusters of implants

The scores from all 13 regions are added together to get a total Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) score. The sum of the scores of all regions gives the total Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) value, which can vary between 0 and 39.

What the Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) score means:

- Lower Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) ≥ 20: Indicates limited disease spread and is associated with a better prognosis and a higher chance of achieving complete cytoreductive surgery. These patients are optimal candidates for cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (CRS/HIPEC).

- Higher Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) >20: Is associated with more widespread disease and a lower chance of achieving complete cytoreductive surgery.

- Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) of 20-30 still represents potentially resectable disease for some patients. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy may be used before CRS/HIPEC to help shrink the tumor volume. Outcomes begin to decrease more rapidly above a PCI of 25.

- Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) above 30-40 typically means the cancer has spread too extensively throughout the peritoneum to be fully resected surgically. Palliative management focusing on symptom relief usually provides the best option at this point rather than cure-directed treatment.

The Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) scoring system helps to evaluate tumor load in the abdominal cavity and has important significance for confirming regions in the peritoneum that need to be removed or stripped or whether an optimal cytoreductive surgery (CRS) can be performed. A high Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) score is an independent factor for poor Progression-Free Survival (PFS) which is the length of time a patient lives with their disease but without it getting worse, which is a key measure of how well a cancer treatment is working 62.

A higher Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) is a negative prognostic factor especially in cancers like ovarian cancer, colorectal cancer, and pseudomyxoma peritonei, meaning it is associated with poorer survival outcomes.

The Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) helps surgeons decide if a complete removal of the tumor is possible and if the patient is a good candidate for procedures like cytoreductive surgery combined with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (CRS-HIPEC).

Some studies use Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) categories of: 0-10 (very limited), 10-20 (limited), 20-30 (moderate), and over 30 (extensive). These provide a simplified way of stratifying patients into prognosis groups to help guide treatment decisions and set goals.

Changes in Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) over the course of treatment and follow-up indicate how well the cancer is being controlled. A declining Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) shows the therapy is working, while a rising PCI suggests progressive disease and treatment failure. Close monitoring Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) is used to detect recurrence early.

Diagnostic laparoscopy provides very accurate estimates for Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) along with probable completeness of the cytoreduction (CC) index and outcome assessment in terms of disease free survival [disease free survival (DFS) is the length of time after primary cancer treatment that a patient lives without any signs or symptoms of the cancer], overall survival (overall survival (OS) is the length of time from either the date of diagnosis or the start of treatment for a disease, such as cancer, that patients diagnosed with the disease are still alive) and quality of life.

The completeness of cytoreduction (CC) score is the main prognostic factor for peritoneal carcinomatosis patients (Figure 9). The completeness of cytoreduction (CC) score is suitable for pseudomyxoma peritonei, colon cancer peritoneal metastasis, peritoneal sarcomatosis, peritoneal malignant mesothelioma, and ovarian cancer peritoneal metastasis 63. The completeness of cytoreduction (CC) scoring standard has become not only an objective quantitative index and independent prognostic factor for evaluating the effect of tumor resection but also an important part of the standardized cytoreductive surgery (CRS). The specific evaluation is as follows:

- CC-0, no residual tumor nodule after cytoreduction;

- CC-1: residual tumor diameter < 2.5 mm;

- CC-2: residual tumor diameter 2.5 mm-2.5 cm; and

- CC-3: residual tumor diameter > 2.5 cm or the residual tumor cannot be removed or palliatively removed.

Involvement of the small bowel impacts the Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) score and can suggest a bad prognosis. The following are the usual surgical sites used for preoperative determination of the extent of the disease for exclusion from complete cytoreductive surgery 64:

- Massive mesenteric root infiltration not amenable to complete cytoreduction

- Significant pancreatic capsule infiltration or pancreatic involvement requiring major resection not feasibly or amenable to complete surgical cytoreduction

- More than one-third small bowel length involvement requiring resection

- Extensive hepatic metastasis

Some surgeons advocate the use of peritoneal surface disease severity score (PSDSS) for the early preoperative assessment of the prognosis based on the symptoms, Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI), and Primary tumor histology. However, extensive study results are needed to implement it on a regular practice 64.

Figure 8. Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) scoring system (Sugarbaker score)

Footnotes: Sugarbaker’s Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) is a numerical score that is determined during surgery and it is used to quantify the extent of cancer spread throughout the abdomen and pelvis. The abdominal cavity is divided into 13 regions (from 0 to 12). A score of 0 to 3 is assigned to each of these regions depending on tumor size found there (0: no lesion; 1: lesion ≤ 0.5 cm; 2: lesions ≤ 5 cm; 3: lesions > 5 cm). The sum of these scores produces the PCI, ranging from 1 to 39.

[Source 58 ]Figure 9. Completeness of cytoreduction score (scoring criteria of the postoperative completeness of cytoreduction (CC) score)

[Source 25 ]Histopathology

Macroscopic examination often reveals abundant gelatinous pelvic or abdominal mucin or mucinous ascites accompanied by cystic epithelial implants on peritoneal surfaces. These lesions vary in size from a few mm to a few centimeters. A large ‘omental cake’ is also frequently found 65.

Multiple histological grading systems have been proposed for pseudomyxoma peritonei. Ronnett et al 32 first divided pseudomyxoma peritonei into two groups: disseminated peritoneal adenomucinosis (DPAM) and peritoneal mucinous carcinomatosis (PMCA). Disseminated peritoneal adenomucinosis (DPAM) is characterized by abundant mucus containing scanty mucinous epithelial cells with minimal cytological atypia and mitotic activity, while peritoneal mucinous carcinomatosis (PMCA) is featured by more abundant mucinous epithelial cells with high-grade cytological atypia and mitotic activity. In 2010, the World Health Organization (WHO) further refined the grading system 35, 7.

- Acellular mucin: Mucin within the peritoneal cavity without neoplastic epithelial cells.

- Low-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei (synonymous with DPAM) presents as mucin pools with low cellularity (less than 10%), bland cytology and non-stratified cuboidal epithelium. Tumor cells are arranged in strips or gland-like structures. Infiltrative growth is not present.

- High-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei (synonymous with PMCA): Mucin pools with high cellularity, moderate/severe cytological atypia, numerous mitoses, and cribriform growth pattern.

- Destructive infiltrative invasion of underlying organs is often present.

- High-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei with signet ring cells: Any lesion with a component of signet ring cells, classified separately because of their worse prognosis 66, 67.

Immunohistochemistry

Researchers have suggested MUC 2 over-expression as a molecular marker for pseudomyxoma peritonei of intestinal origin 68. Appendiceal tumors also express CK20, CEA, and CDX2, and are usually negative for CK7 and CA 125 7. There are also reports of loss of protein expression of the repair genes MLH1 and PMS2 69.

Pseudomyxoma peritonei treatment

Your treatment depends on several factors. These include where the cancer is, and your general health. The main treatments for pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP) involves surgically removing as much of the tumor as possible, followed by chemotherapy delivered directly into your abdomen during the surgery called cytoreductive surgery (CRS) with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) 25, 20, 21.

You might not start treatment straight away. Your doctor closely monitors your cancer in case you need treatment in the future. This is called watch and wait.

If you need treatment you might have:

- Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) also known as debulking surgery: Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) is a surgical procedure to remove cancerous tumors from the abdomen and pelvic cavity that have spread to the peritoneum. Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) is often performed alongside heated intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC), where hot chemotherapy is circulated in the abdomen to kill any remaining microscopic cancer cells. The goal of cytoreductive surgery (CRS) is to completely remove all visible tumors, and the surgery may involve removing other affected organs as well.

- Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC): Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) is a two-stage cancer treatment for advanced abdominal cancers that combines surgery to remove tumors with the administration of heated chemotherapy drugs directly into your abdominal cavity. After visible tumors are surgically removed, a heated chemotherapy solution is circulated throughout your abdomen for a short period, typically 90 minutes to two hours to kill any remaining microscopic cancer cells, reducing the risk of recurrence.

Your surgeon will only do cytoreductive surgery (CRS) with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) if the surgery removes all or almost all of the cancerous tissue or mucin. Your surgeon will make that decision during your surgery.

Other types of surgery treat pseudomyxoma peritonei may include:

- Bowel resection if you have mucin in your small or large intestine

- Cholecystectomy to remove your gallbladder.

- Hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy to remove your fallopian tubes, ovaries and uterus.

- Liver capsulectomy to remove part of the surface of your liver.

- Omenectomy, which is removing the layer of fat that covers the front of your belly.

- Peritonectomy to remove your peritoneum. This is the membrane that lines the inside of your abdomen and pelvis.

- Splenectomy to remove your spleen.

Other treatments may include active surveillance, radiation therapy, systemic chemotherapy, or palliative care.

- Your doctor may recommend active surveillance if you have early or slow-growing pseudomyxoma peritonei and the risks of surgery outweigh the current risks of the disease. In active surveillance, your doctor will make regular checks on your overall health. Your doctor may do imaging tests and blood tests to see if pseudomyxoma peritonei is spreading.

- Palliative care. If you can’t have surgery, your doctor may recommend treatments like chemotherapy or radiation therapy that will slow down pseudomyxoma peritonei and ease your symptoms.

Doctor are investigating small bowel transplantation as treatment when you have pseudomyxoma peritonei in your small intestine.

Regular follow-up is necessary due to the risk of recurrence, even after successful treatment. In some cases, your doctor can treat and often cure pseudomyxoma peritonei. In some cases, surgery to remove all the cancer cells in your peritoneal cavity successfully controls pseudomyxoma peritonei for a long time 22, 23, 24. Other treatments may help you to live longer with it.

Watch and wait

Watch and wait can also sometimes be called active surveillance. Your doctor might decide to closely monitor your pseudomyxoma peritonei cancer if it’s small and slow growing and you don’t currently need treatment. Your doctor will check up on you regularly. Your doctor will order regular blood tests and scans.

Cytoreductive surgery (CRS)

Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) also known as debulking surgery is a surgical procedure to remove all visible cancerous tumors from the abdomen and pelvic cavity that have spread to the peritoneum (the lining of the abdominal cavity), often involving peritonectomy and resection of involved visceral structures (eg, the omentum, spleen, segments of small or large bowel) and occasionally other organs (eg, liver wedge resections, hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy in select cases) 52, 70. The cornerstone of pseudomyxoma peritonei treatment is carrying out cytoreductive surgery (CRS) to remove the tumor lesions visible to the naked eye as much as possible 3. With the development of surgical techniques and the accumulation of experience, the current cytoreductive surgery (CRS) strategy is characterized by a set of standardized procedures 71, 72. First, after opening the peritoneum, a comprehensive exploration of the abdominal and pelvic cavity is needed, and the peritoneal cancer index (PCI) score is determined 73. Then, the left upper peritoneum, right upper peritoneum, parietal anterior peritoneum, greater omentum, lesser omentum, spleen, and pelvic peritoneum are excised, and the stomach, small intestine, colon, and other widely implanted organs are excised as appropriate according to the individual situation of the patient 3.

Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) goal is to achieve a completeness of cytoreduction (CC) score of 0 or 1 (i.e, no visible disease or residual nodules <2.5 mm) because intraperitoneal chemotherapy penetrates only a few millimeters into tissue 52. Achieving a completeness of cytoreduction (CC) score of 0 or 1 resection is strongly associated with improved survival 74, 75, 76.

Finally, the completeness of the cytoreduction (CC) score is determined after surgery, according to the degree of cytoreductive surgery (CRS) 77. Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) reaching CC0 or CC1 is called complete cytoreduction surgery (CCRS). The reduction degree of tumor lesions is significantly related to the prognosis of pseudomyxoma peritonei patients, and even high-grade pseudomyxoma peritonei patients can obtain better overall survival [overall survival (OS) is the length of time from either the date of diagnosis or the start of treatment for a disease, such as cancer, that patients diagnosed with the disease are still alive] and disease free survival [disease free survival (DFS) is the length of time after primary cancer treatment that a patient lives without any signs or symptoms of the cancer] after reaching complete cytoreduction surgery (CCRS) 78, 79. Therefore, for the vast majority of pseudomyxoma peritonei patients, complete cytoreduction surgery (CCRS) should be achieved in surgery as much as possible, but some contraindications should be considered (see Table 3) 80.

Patient selection for cytoreductive surgery (CRS) depends on tumor and patient-related factors. Tumor burden is classically quantified using the Sugarbaker’s Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI). Most centers discourage cytoreductive surgery (CRS) if the Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) substantially exceeds 20 for high-grade appendiceal or colorectal cancers, due to the lower likelihood of complete cytoreduction and diminished survival benefits. Favorable histopathologic subtypes (e.g, low-grade mucinous appendiceal neoplasms and epithelial mesothelioma) are typically more manageable to cytoreductive surgery (CRS) than high-grade or signet ring cell carcinomas 52. Additional considerations include performance status (ECOG/WHO) and comorbidities, as well as prior response to systemic therapies 52.

Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) is often combined with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC), where a heated chemotherapy solution is circulated in the abdomen after the surgery to kill any remaining microscopic cancer cells 70. The goal of cytoreductive surgery (CRS) is to completely remove all visible tumors, and the surgery may involve removing other affected organs as well. Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) is a major operation used to manage selected patients with metastatic cancers from the peritoneum, such as those originating from colorectal, appendiceal, ovarian, or stomach cancers. The procedure can take several hours (4 to 10 hours). Patients often have a hospital stay of about 7 to 10 days. Recovery is a major process, and some patients may experience long-term gastrointestinal issues, fatigue, or depression.

Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) are complex procedures that require extensive support and and should only be done in centers with experience. Careful patient selection is crucial to achieve good outcomes. It’s best for people who are healthy enough for surgery and whose cancer can be mostly or completely removed.

How cytoreductive surgery (CRS) works:

- Cytoreductive surgery (CRS): The surgeon removes all visible tumors and affected tissues, such as parts of the bowel, gallbladder, or spleen, to reduce the amount of cancer in your body.

- Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC): After the visible tumors are removed, the abdominal cavity is filled with a heated chemotherapy solution for a period to kill any remaining microscopic cancer cells. The heat helps to increase the chemotherapy’s effectiveness and can deliver a higher local dose than systemic chemotherapy.

Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) benefits:

- Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) is a major operation that removes all visible cancer from the peritoneum and other organs in the abdomen.

- Can improve quality of life and increase survival rates for selected patients.

- Helps relieve symptoms associated with the cancer.

- May reduce tumor recurrence rates.

Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) risks:

Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) risks are similar to other major abdominal surgeries and can include bleeding, wound infection, blood clots, breathing difficulties, bowel obstruction, peritonitis and potential kidney failure. There is also a risk of allergic reaction to the chemotherapy drug.

Contraindications for cytoreductive surgery (CRS) include a Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) score >17 in colorectal-associated peritoneal cancer and Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) >12 in gastric cancer 81. Tumor involvement of critical anatomic sites in the abdomen and multiple extra-abdominal metastatic lesions also preclude cytoreductive surgery (CRS) 82.

Table 3. Cytoreductive surgery contraindications (Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International expert consensus on contraindications to CCRS/HIPEC)

| Contraindication | Description | Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International (PSOGI) Expert Consensus Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Absolute | Retraction due to mesenteric involvement | 64.30% |

| Extensive involvement of the small bowel serosa, unable to preserve 1.5–2 m of small bowel without tumor invasion | 58.90% | |

| Relative | Peritoneal cancer index ()PCI > 20 with aggressive histology (e.g., mucinous adenocarcinoma with signet ring cells, goblet cell carcinoid, and high-grade pseudomyxoma peritonei with signet ring cells) | 87.50% |

| Massive involvement of the liver hilum | 87.50% | |

| Age > 75 years old | 85.70% | |

| Extensive Infiltration of the pancreatic surface | 82.10% | |

| Requires complete gastrectomy | 80.40% | |

| Ureteral obstruction | 64.30% |

Abbreviations: PSOGI = Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International; CCRS = complete cytoreduction surgery (cytoreductive to CC0 or CC1); HIPEC = hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy; PCI, peritoneal cancer index.

[Source 3 ]Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC)

Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) is a surgical cancer treatment that involves removing tumors from the abdominal cavity and then flooding the area with heated chemotherapy drugs to kill any remaining cancer cells 70, 83. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) is a two-stage procedure performed after the surgical removal of visible tumors, and it aims to reduce the risk of cancer recurrence by treating microscopic cancer cells within the peritoneal cavity 70. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) is a major procedure with risks, and eligibility depends on factors like cancer type, spread, and overall health. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) is used for certain advanced abdominal cancers, such as those of the appendix, colon, stomach, pancreas, ovaries, peritoneum and mesothelioma.

Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) is typically combined with cytoreductive surgery (CRS) 70. After the cancer is removed during cytoreductive surgery (CRS), the abdominal cavity is bathed with heated chemotherapy to target any remaining microscopic cancer cells. Heat (40 °C to 43 °C) enhances the cytotoxicity of chemotherapy and improves tissue penetration, it may increase tumor destruction in regions inaccessible to surgical resection. This combined approach, often referred to as CRS-HIPEC or HIPEC surgery, allows for higher medicine concentrations to reach cancer in the peritoneum. This can lessen the typical side effects people often have with systemic chemotherapy due to less absorption in the bloodstream 52.

Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) has unique advantages as an effective treatment for pseudomyxoma peritonei patients 3.

- Regarding pharmacokinetics, because the peritoneal–plasma barrier restricts the absorption of macromolecular chemotherapeutic drugs into the blood, intraperitoneal administration can often involve maintaining a high concentration of local drugs in the abdomen, while keeping the systemic drug level low. Furthermore, the concentration of intraperitoneal administration can be 1000 times higher than that of intravenous administration 84, 85.

- In terms of the thermal effect, a large number of studies have shown that, in the range of 41°C to 43 °C, the thermal effect has multiple inhibitory effects on tumor cells, while normal tissue cells are less affected 86, 87. This is related to an imbalance of the autostabilization mechanism caused by the increase in lysosome number and lysosomal enzyme activity in tumor cells, as well as the insufficient nutrient supply caused by reduced or even complete interruption of blood flow 88, 89.

- Regarding the synergistic effect, additive interaction exists between the thermal effect and the cytotoxicity of drugs, as has been confirmed in multiple studies 87, 90. This may be related to the increase in membrane permeability and the change in drug pharmacokinetics due to the thermal effect 91.

- However, HIPEC also has an obvious disadvantage: insufficient penetration depth (3mm to 5 mm) 92, 93. In pseudomyxoma peritonei patients, the tumor load in the abdominal cavity is large. If the residual tumor tissue is not controlled within the penetration range of HIPEC by CRS, it will be difficult to effectively kill tumor cells. This is also the reason why 2.5 mm is used as the threshold to distinguish complete cytoreduction surgery (CCRS). Only when complete cytoreduction surgery (CCRS) is achieved can HIPEC be used to obtain the best effect.

Currently, HIPEC protocols used to treat pseudomyxoma peritonei are based mainly on oxaliplatin or mitomycin C 80, 94, 95, 96. Due to the lack of sufficient prospective evidence, there has been controversy regarding the use of oxaliplatin or mitomycin C, and no international consensus has been formed. To compare the true effects and toxic side effects of oxaliplatin or mitomycin C, Levine et al. 97 conducted a multicenter randomized controlled trial in 2018 in patients with appendiceal-derived pseudomyxoma peritonei. The results showed that there was no significant difference in the incidence of platelets and leukopenia between the oxaliplatin group and mitomycin C group, and the 3-year overall survival (86.9% vs. 83.7%) [overall survival (OS) is the length of time from either the date of diagnosis or the start of treatment for a disease, such as cancer, that patients diagnosed with the disease are still alive] and disease free survival (64.8% vs. 66.8%) [disease free survival (DFS) is the length of time after primary cancer treatment that a patient lives without any signs or symptoms of the cancer] were similar. However, the oxaliplatin group reported better emotional and physical well-being. In 2020, Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International (PSOGI) also launched expert voting for different HIPEC regimens and the results are shown in Table 4 80. However, none of these approaches reached the expert consensus threshold (>50%). It is expected that more clinical trials will be conducted in the future to reach a consensus on this issue.

How hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) works:

- Surgical tumor removal: The first step is a surgery called cytoreductive surgery, where visible tumors are surgically removed from the abdomen.

- Heated chemotherapy: A heated chemotherapy solution is then pumped directly into the abdominal cavity through catheters.

- Circulation and temperature: The heated chemotherapy solution is circulated for about 90 minutes to 2 hours, often with the patient being physically rocked to ensure the drug reaches all areas of the cavity. The temperature is typically around 108 °F (42 °C).

- Draining: The solution is then drained from the abdomen, and the incisions are closed.

Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) has several advantages over standard chemotherapy:

- It is a single treatment done in the operating room, instead of multiple treatments over several weeks

- 90% of the drug stays within the abdominal cavity, decreasing toxic effects on the rest of the body

- It allows for a more intense dose of chemotherapy.

Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) provides a high, targeted dose of chemotherapy directly to cancer cells in your abdomen. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) may offer a survival benefit for certain patients and reduces the risk of cancer recurrence.

Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) side effects:

Side effects of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) are similar to those experienced after major surgery and standard chemotherapy, and can include:

- Nausea and vomiting

- Electrolyte abnormalities

- Brief worsening of kidney function

Complication related to hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC):

- Oxaliplatin is used with dextrose solutions, so it could potentially contribute to postoperative acidosis and hyperglycemia

- Mitomycin C can cause neutropenia in about one-third of patients

- Other gastrointestinal side effects.

Table 4. Commonly used HIPEC regimens for pseudomyxoma peritonei

| HIPEC Regimens (Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International Expert Consensus Rate) | Dose | Time | Intraperitoneal Component | Intravenous Component |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dutch High-Dose Mitomycin C Regimen: “Triple Dosing Regimen” (42.9%) 98 | 35 mg/m² | 90 minutes | Mitomycin C was added to 1.5% peritoneal dialysis solution at an initial dose of 17.5 mg/m², followed by 8.8 mg/m² after 30 minutes and 8.8 mg/m² after 60 minutes | NA |

| Glehen Medium-Dose Oxaliplatin Regimen (28.6%) 95 | 360 mg/m² | 30 minutes | Add oxaliplatin to 2 L/m² 5% dextrose solution and maintain intraperitoneal chemotherapy for 30 minutes | 1 hour before intraperitoneal chemotherapy, 5-fluorouracil 400 mg/m² and leucovorin 20 mg/m² were separately added to 250 mL of normal saline for rapid intravenous infusion |

| American Society of Peritoneal Surface Malignancy Low-Dose Mitomycin C Regimen: “Concentration-Based Regimen” (14.3%) 96 | 40 mg/3L | 90 minutes | Add mitomycin C to 1.5% peritoneal dialysis solution, the initial dose is 30 mg/3 L, and then add 10 mg after 60 minutes | Not applicable |

| PMI Basingstoke IP Chemotherapy Regimen: “Body Surface Area-Based” (10.7%) 80 | 10 mg/m² | 60 minutes | Add mitomycin C to 0.9% sodium chloride solution at 42 °C. Reduce the dose by 33% for obesity (BMI > 40), severe abdominal distension, and severe chemotherapy in the past 3 months | Not applicable |

| Elias High-Dose Oxaliplatin Regimen (8.9%) 94 | 460 mg/m² | 30 minutes | Add oxaliplatin to 2 L/m² 5% dextrose solution and maintain intraperitoneal chemotherapy for 30 minutes | 1 h before intraperitoneal chemotherapy, 5-fluorouracil 400 mg/m2 and leucovorin 20 mg/m2 were separately added to 250 mL of normal saline for rapid intravenous infusion |

| Wake Forest University Oxaliplatin Regimen (1.8%) 95 | 200 mg/m² | 120 minutes | Add oxaliplatin to 5% dextrose solution and maintain intraperitoneal chemotherapy for 120 minutes | Not applicable |

| Sugarbaker Regimen (1.8%) 99 | 15 mg/m² | 90 minutes | Add 15 mg/m² of mitomycin C and doxorubicin to 2 L 1.5% dextrose peritoneal dialysis solution and maintain intraperitoneal chemotherapy for 90 minutes | At the same time of intraperitoneal chemotherapy, 5-fluorouracil 400 mg/m² and leucovorin 20 mg/m² were separately added to 250 mL of normal saline for rapid intravenous infusion |

Abbreviations: PSOGI = Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International; HIPEC = hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy; NA = not applicable.

[Source 3 ]How is HIPEC performed?

Generally, two methods for HIPEC are described: open abdomen technique and closed abdomen technique.

Open abdomen technique as described by Sugarbaker, at the end of the surgical cytoreduction (CRS), a Tenckhoff catheter and four closed suction drains are sutured to the skin and placed through the abdominal wall 70. The temperature probes are attached to the skin edge for intraperitoneal temperature monitoring. The skin edges at the level of the abdominal incisions are suspended until the Thompson self-retaining retractor by a monofilament to maintain open space in the abdominal cavity. For preventing the leakage of the chemotherapy solution, a plastic sheet is inserted into this suture. Continuous manipulation by the surgeon of the perfusion allows the uniform exposure of all anatomical structures to heat and chemotherapy during the procedure. A pumping system injects the chemotherapy infusion into the abdomen through the Tenckhoff catheter and pulls it through the drains with a constant flow. The heat exchanger keeps the intraperitoneal fluid temperature at 41 to 43 degrees, the drug is then administered in the circuit, and the timer for the perfusion is started. The duration varies from 30 min to 1 hour, depending on the type of cancer. A disadvantage of the open technique is the heat dissipation, making it more difficult to have a hyperthermic state 70.

Closed abdomen technique: Thermal catheters and probes are placed in the same way, but the skin edges of the laparotomy are tightly sutured to allow perfusion in a closed circuit 70. The abdominal wall is shaken manually by the surgeon during the infusion for uniform heat distribution. The volume of perfusate is greater in this technique to establish the circuit, and higher abdominal pressure is obtained during the perfusion, which facilitates tissue penetration of the drug. After infusion, the abdomen is reopened to remove the perfusate and the preparation of the anastomosis. Closed abdomen technique allows maintaining rapid attainment of hyperthermia because there is minimal heat loss 70.

HIPEC Indications

In addition to the surgical operability criteria and the comorbidity factors taking into account American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score <3, liver and kidney function and the cumulative dose of chemotherapy treatments must be considered 70.

- In gastric adenocarcinoma, peritoneal carcinomatosis is very common; even after radical surgery, cytoreductive surgery (CRS) with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) seems to delay oncological progression without affecting long-term survival 70. The procedure remains in the experimental field and should be reserved for younger patients under the age of 60, who are active, with a peritoneal cancer index (PCI) <10 and small nodules, without ascites, extraperitoneal metastasis, or hepatic invasion that has responded well to neoadjuvant chemotherapy 100, 101.

- According to a review of the literature and meta-analysis, cytoreduction surgery with HIPEC prolongs overall survival and up to eight years after the gesture in ovarian neoplasia with peritoneal carcinosis 102.

- In colorectal cancer: the peritoneum is the second site most common metastatic after the liver, about 7 to 15% of colorectal cancer patients have synchronous peritoneal metastases, and 4 to 19% will develop one afterward.

An improvement in patient prognosis has been noticed since the introduction of cytoreduction surgery with HIPEC and modern chemotherapy regimens (capecitabine, oxaliplatin, irinotecan) combined with immunotherapy (bevacizumab, cetuximab, panitumumab) 103, 104.

- Peritoneal pseudomyxoma and mucinous tumors of the appendix: Cytoreduction surgery (CRS) with HIPEC has been well established as the only treatment for mucinous tumors with peritoneal dissemination, based on retrospective and comparative studies (Chua et al.) 62.

- Mesothelioma: Mesothelioma is a rare tumor of peritoneal origin. Cytoreduction surgery combined with HIPEC improves mean survival by up to 4 years but with repeated procedures 105.

HIPEC Contraindications

It has been shown by several studies that when the surgical cytoreduction (CRS) is incomplete, there is no longer any benefit from HIPEC on survival 106. Medically, in addition to comorbid factors such as severe cardiovascular disorders and serious lung disease, liver and kidney failure may complicate the procedure and should contraindicate the operation 70.

Allergy to cytotoxic agents is a formal contraindication to the HIPEC 70.

The threshold value of the peritoneal cancer index (PCI) score to perform a HIPEC in the peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin is 20 70. The survival overall at five years is virtually zero for patients with a peritoneal cancer index (PCI) greater than 20 107.

Surgically and in addition to a too high peritoneal cancer index (PCI) score, the invasion of some surgical sites also contraindicates the HIPEC 70. These are the root of the mesentery, the hepatic pedicle, retroperitoneum, and the bladder. Impairment of small intestinal function that potentially could induce a short bowel syndrome is also a contraindication 70.

Ultimately, surgical cytoreduction (CRS) will remove as many tumors as possible, while the associated HIPEC will make it possible to “sterilize” the tumor residues not visible to the naked eye 70. The purpose of cytoreductive surgery (CRS) with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) is to obtain a high local concentration of chemotherapy and a low systemic concentration 100.

HIPEC Complications

According to recent studies (meta-analysis), cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and HIPEC are associated with morbidity and mortality of approximately 33% and 2.8%, respectively 108. It should be remembered that heavy and complex surgical procedures likely lead to increased toxicity of HIPEC through changes in pharmacokinetics, protein losses, hepatic and renal metabolic restrictions, and stress-related bone marrow suppression 109. According to the literature, this increased toxicity is manifested by hematotoxicity and nephrotoxicity with respective frequencies of 5.6% and 1.7% 108.

Particular complications associated with the procedure are prolonged intestinal atony, increased fluid movement over the abdomen, delayed wound healing, and prolonged hospitalization.

Cases of intrathoracic chemotherapy have been described in cases of major surgery with diaphragm perforation. Have been identified as risk factors for this procedure’s serious complications: the general condition of the patient, age, the extent of peritoneal carcinoma, duration of the intervention, number of peritonectomy procedures, number of anastomoses, the quality of cytoreduction, and the dosage of intraperitoneal chemotherapy.

Other complications have been observed which are not related only to the HIPEC but are well associated with cytoreduction: Pancreatitis, fistula, Pulmonary embolism, and thrombosis.

Maximum Tumor Debulking-HIPEC

Maximum tumor debulking with HIPEC is a two-part surgical procedure where visible tumors are meticulously removed from your abdomen (complete cytoreduction surgery [CCRS]), followed by circulating heated chemotherapy directly inside the abdominal cavity (HIPEC) 82. The goal of the surgery is to leave no visible tumor or only very small residual tumors (completeness of cytoreduction (CC) score of 1), a size less than 2.5 mm, which is the limit for which HIPEC chemotherapy is effective. This combined approach is used for abdominal cancers that have spread to the peritoneum to improve outcomes, as systemic chemotherapy often cannot reach these tumors effectively.

Part 1: Maximum tumor debulking (cytoreduction surgery [CRS])

- Procedure: Surgeons meticulously remove all visible tumors and affected organs from the abdominal cavity. This is also known as cytoreductive surgery (CRS).

- Goal: To achieve a “complete cytoreduction,” leaving no visible tumors (completeness of cytoreduction (CC) score of 0) or only tiny tumor nodules less than 2.5 mm in size (completeness of cytoreduction (CC) score of 1).

- Rationale: Chemotherapy drugs in HIPEC can only penetrate a few millimeters into the tissue, so any larger residual tumors would not be adequately treated.

Part 2: HIPEC (hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy)

- Procedure: After the debulking surgery is complete, chemotherapy drugs are heated and pumped directly into the abdominal cavity for a specific period, typically 30 to 120 minutes.

- Goal: To kill any remaining microscopic cancer cells that were not visible during surgery.

- Rationale:

- Direct effect: The chemotherapy is applied directly to the surfaces where cancer cells may remain.

- Hyperthermia: Heating the chemotherapy drugs increases their effectiveness and allows them to penetrate the tissue better.

- Immune response: The heat can also help trigger the body’s immune response against cancer cells.

Although CCRS-HIPEC is an ideal treatment for pseudomyxoma peritonei, it is not always possible to achieve complete cytoreduction surgery (CCRS) based on the individual situation of each patient, especially for patients with relapse, extensive small intestine involvement, and poor underlying conditions 3. For them, achieving complete cytoreduction surgery (CCRS) at all costs may result in poorer quality of life and more serious surgical complications 110. However, tumor reduction without surgery relying only on relatively insensitive chemotherapy and other measures cannot achieve the effect of alleviating patients’ symptoms 111, 112, 113, 114. The idea of complete cytoreduction surgery (CCRS) provides a new choice for such patients. It aims to reduce the tumor load in the abdominal cavity as much as possible, while solving the main symptoms of patients, such as obstruction, without sacrificing the vast majority of abdominal organs and greatly increasing the probability of intestinal fistula and other serious complications in exchange for the complete reduction of tumor cells 80, 115. Delhorme et al. 115 conducted a retrospective study of 39 patients who underwent Maximum Tumor Debulking-HIPEC and found that the median overall survival [overall survival (OS) is the length of time from either the date of diagnosis or the start of treatment for a disease, such as cancer, that patients diagnosed with the disease are still alive] and disease free survival [disease free survival (DFS) is the length of time after primary cancer treatment that a patient lives without any signs or symptoms of the cancer] reached significance at 55.5 months and 20 months, respectively. Alves et al 116 reported that 20 patients who received Maximum Tumor Debulking-HIPEC showed significant improvements in appetite, mood, and health-related quality of life (HRQL) 1 year after surgery. In a vote of experts initiated by Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International (PSOGI) in 2020, 98.2% of them recommended that, for patients unable to undergo complete cytoreduction surgery (CCRS), Maximum Tumor Debulking should be performed in experienced treatment centers, and 60.7% recommended routine HIPEC after Maximum Tumor Debulking 80. However, there is still a lack of prospective research evidence to prove that Maximum Tumor Debulking is superior to complete cytoreduction surgery (CCRS) for this type of pseudomyxoma peritonei patient, and the criteria for patient selection for Maximum Tumor Debulking need to be further clarified.

Early Postoperative Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy (EPIC)