Contents

- Intracerebral hemorrhage

- Intracerebral hemorrhage causes

- Intracerebral hemorrhage symptoms

- Intracerebral hemorrhage diagnosis

- Intracerebral hemorrhage treatment

- Intracerebral hemorrhage recovery

Intracerebral hemorrhage

Intracerebral hemorrhage is defined as bleeding within the brain, it is a type of stroke and is a serious life-threatening medical emergency. Intracerebral hemorrhage occurs when a diseased blood vessel within the brain bursts, allowing blood to leak inside the brain. The sudden increase in pressure within the brain can cause damage to the brain cells surrounding the blood. If the amount of blood increases rapidly, the sudden buildup in pressure can lead to unconsciousness or death. Intracerebral hemorrhage usually occurs in selected parts of the brain, including the basal ganglia, cerebellum, brain stem, or cortex. Causes of intracerebral hemorrhage include a bleeding aneurysm, an arteriovenous malformation (AVM), or an artery wall that breaks open. Intracerebral hemorrhage is a major public health problem 1 with an annual incidence of 10–30 per 100 000 population 2, accounting for 2 million (10–15%) 3 of about 15 million strokes worldwide each year 4.

There are two types of stroke – ischemic stroke and hemorrhagic stroke. Hemorrhagic stroke is the less common type. Hemorrhagic strokes make up about 13 percent of stroke cases 5. Hemorrhagic stroke is caused by a weakened vessel that ruptures and bleeds into the surrounding brain. The blood accumulates and compresses the surrounding brain tissue. The two types of hemorrhagic strokes are intracerebral hemorrhage or subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Intracerebral hemorrhage while accounting for just 10 to 25% of total strokes, is responsible for greater than half of stroke-related deaths, and less than half of intracerebral hemorrhage patients survive for 1 year 6. Survivors of intracerebral hemorrhage often suffer severe morbidity, with just 20% living independently at 6 months 7. Despite efforts to improve therapy and develop new treatments for the disease, the overall mortality rate for intracerebral hemorrhage has not declined in the past 10 years, and many recent clinical trials for novel surgical or pharmaceutical interventions have failed to show substantial benefit 6.

Hospital admissions for intracerebral hemorrhage have in creased by 18% in the past 10 years 8, probably because of increases in the number of elderly people 9, many of whom lack adequate blood-pressure control, and the increasing use of anticoagulants, thrombolytics, and antiplatelet agents. Mexican Americans, Latin Americans, African Americans, Native Americans, Japanese people, and Chinese people have higher incidences than do white Americans 10. These differences are mostly seen in the incidence of deep intracerebral hemorrhage and are most prominent in young and middle-aged people. Incidence might have decreased in some populations with improved access to medical care and blood-pressure control 11.

Symptoms of stroke are:

- Sudden numbness or weakness of the face, arm or leg (especially on one side of the body)

- Sudden confusion, trouble speaking or understanding speech

- Sudden trouble seeing in one or both eyes

- Sudden trouble walking, dizziness, loss of balance or coordination

- Sudden severe headache with no known cause

The main symptoms of stroke can be remembered with the word FAST:

- Face – the face may have dropped on 1 side, the person may not be able to smile, or their mouth or eye may have dropped. Does one side of the face droop or is it numb? Ask the person to smile. Is the person’s smile uneven or lopsided?

- Arms – the person with suspected stroke may not be able to lift both arms and keep them there because of weakness or numbness in 1 arm. Is one arm weak or numb? Ask the person to raise both arms. Does one arm drift downward?

- Speech – their speech may be slurred or garbled, or the person may not be able to talk at all despite appearing to be awake; they may also have problems understanding what you’re saying to them. Is speech slurred? Is the person unable to speak or hard to understand? Ask the person to repeat a simple sentence.

- Time – it’s time to dial your local emergency number immediately if you see any of these signs or symptoms.

It is important to treat strokes as quickly as possible. With an intracerebral hemorrhage, the first steps are to find the cause of bleeding in the brain and then control it. Surgery may be needed. Post-stroke rehabilitation can help people overcome disabilities caused by stroke damage.

If you’re having a stroke, it’s critical that you get medical attention right away. Immediate treatment may minimize the long-term effects of a stroke and even prevent death. Thanks to recent advances, stroke treatments and survival rates have improved greatly over the last decade.

The main symptoms of stroke can be remembered with the word F.A.S.T.:

- Face – the face may have dropped on one side, the person may not be able to smile, or their mouth or eye may have dropped.

- Arms – the person with suspected stroke may not be able to lift both arms and keep them there because of weakness or numbness in one arm.

- Speech – their speech may be slurred or garbled, or the person may not be able to talk at all despite appearing to be awake.

- Time – it’s time to dial your local emergency number immediately if you see any of these signs or symptoms.

If you have any of these symptoms or if you suspect someone else is having a stroke, you must get to a hospital quickly to begin treatment. Acute stroke therapies try to stop a stroke while it is happening by quickly dissolving the blood clot or by stopping the bleeding.

Post-stroke rehabilitation helps individuals overcome disabilities that result from stroke damage. Drug therapy with blood thinners is the most common treatment for stroke.

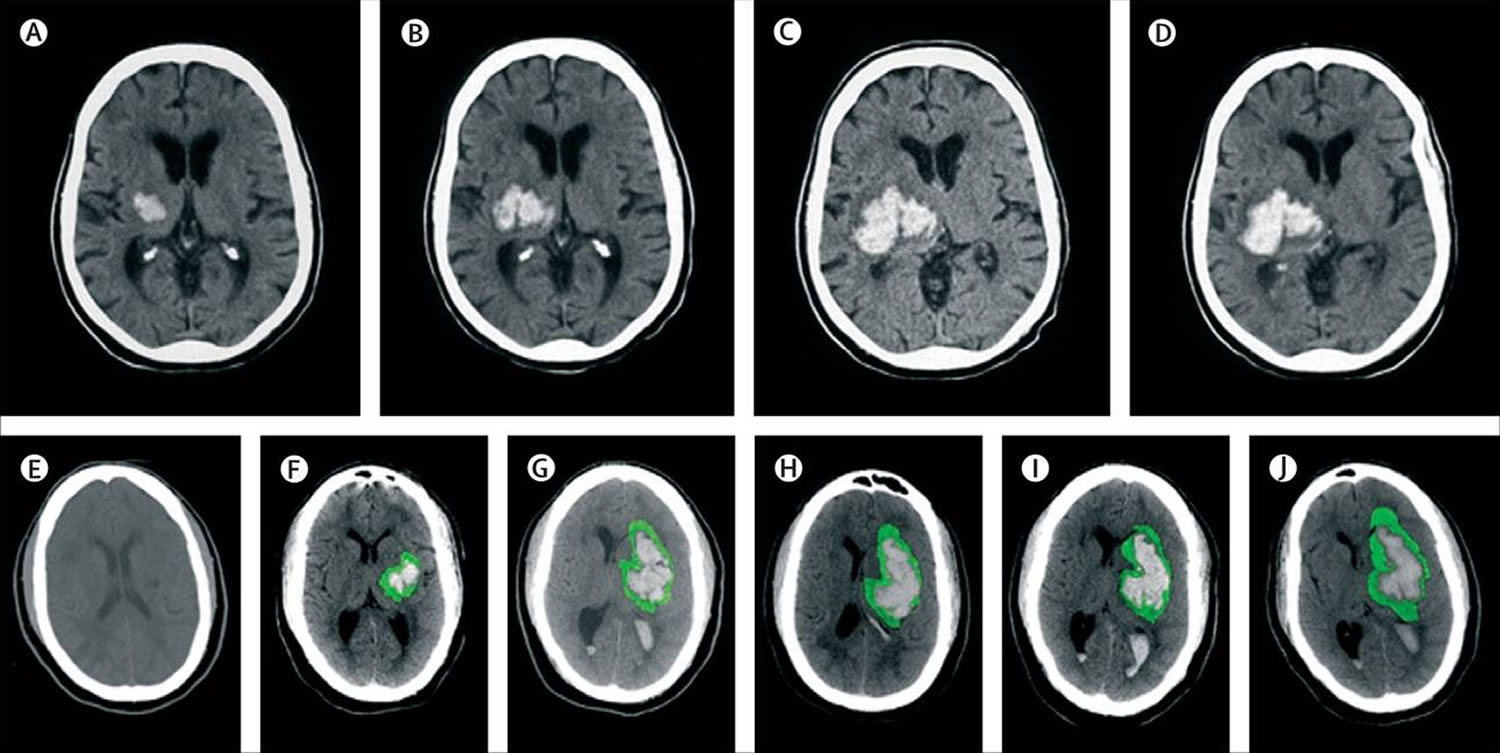

Figure 1. Hemorrhagic stroke

Figure 2. Intracerebral haemorrhage on serial CT scans

Footnote: Top: hyperacute expansion of hematoma in a patient with intracerebral hemorrhage on serial CT scans. Small hematoma detected in the basal ganglia and thalamus (A). Expansion of hematoma after 151 min (B). Continued progression of hematoma after another 82 min (C). Stabilisation of hematoma after another 76 min (D).

Bottom: progression of hematoma and perihematomal edema in a patient with intracerebral hemorrhage on serial CT scans. The first scan (E) was acquired before the intracerebral hemorrhage. Perihematoma edema is highlighted in green to facilitate recognition of progression of edema. At 4 h after symptom onset there is a small hematoma in the basal ganglia (F). Expansion of hematoma with extension into the lateral ventricle and new mass-effect and midline shift at 14 h (G). Worsening hydrocephalus and early perihematomal edema at 28 hours (H). Continued mass-effect with prominent perihematomal edema at 73 hours (I). Resolving hematoma with more prominent perihematomal edema at 7 days (J).

[Source 4 ]Intracerebral hemorrhage causes

The most common cause of intracerebral hemorrhage is high blood pressure (hypertension). Since high blood pressure by itself often causes no symptoms, many people with intracranial hemorrhage are not aware that they have high blood pressure, or that it needs to be treated. Less common causes of intracerebral hemorrhage include trauma, bleeding associated with amyloid angiopathy, infections, tumors, blood clotting deficiencies, hemorrhagic conversion of ischemic stroke, dural venous sinus thrombosis, vasculitis and vascular malformations such as cavernous angiomas, arteriovenous fistulae, arteriovenous malformations (AVMs), venous angiomas, and aneurysms 1. Intracerebral hemorrhage is considered primary if there is not an identifiable underlying structural lesion that is likely to be responsible for the hemorrhage. It is most commonly associated with arteriosclerosis as a result of hypertension and amyloid angiopathy 12.

Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage, i.e., intracerebral hemorrhage that is not related to trauma, most frequently occurs secondary to hypertension, with up to 70% of patients with intracerebral hemorrhage having a history of hypertension 13. Hypertension is a significant contributory factor for intracerebral hemorrhage and is associated with morbidity and mortality in all age groups 14. Chronic hypertension induces degenerative changes in small arterioles, making them prone to rupture. Treatment of hypertension therefore reduces the annual risk of hemorrhage in hypertensive patients. In the elderly, amyloid angiopathy is a significant cause of bleeding. The presence of either the e2 or the e4 allele of the apolipoprotien E gene also increases the risk of intracerebral hemorrhage through β-amyloid deposition and fibrinoid necrosis in the vessel wall, rendering it more likely to rupture 15.

An arteriovenous malformation (AVM) is tangle of blood vessels in the brain that bypasses normal brain tissue and directly diverts blood from the arteries to the veins. A brain arteriovenous malformation (AVM) contains abnormal; therefore, “weakened” blood vessels that direct blood away from normal brain tissue. These abnormal and weak blood vessels dilate over time. Eventually, they may burst from the high pressure of blood flow from the arteries. The chance of a brain arteriovenous malformation bleeding is 1% to 3% per year 16. The risk of recurrent intracranial bleeding is slightly higher for a short time after the first bleed. People who are between 11 to 35 years old and who have an arteriovenous malformation are at a slightly higher risk of bleeding. The risk of death related to each bleed is 10 to 15%. The chance of permanent brain damage is 20 to 30%. Each time blood leaks into the brain, normal brain tissue is damaged. This results in loss of normal function, which may be temporary or permanent.

Brain arteriovenous malformations are usually congenital, meaning someone is born with one. But they’re usually not hereditary. People probably don’t inherit an arteriovenous malformation from their parents, and they probably won’t pass one on to their children. Brain arteriovenous malformations occur in less than 1 percent of the general population. Arteriovenous malformations are more common in males than in females. Brain arteriovenous malformations can occur anywhere within the brain or on its covering. Most arteriovenous malformations don’t grow or change much, although the vessels involved may dilate (widen).

Symptoms of a brain arteriovenous malformation (AVM) may vary depending on where the arteriovenous malformation is located:

- More than 50% of patients with an arteriovenous malformation have an intracranial hemorrhage.

- Among arteriovenous malformation patients, 20 to 25% have focal or generalized seizures.

- Patients may have localized pain in the head due to increased blood flow around an arteriovenous malformation.

- 15% may have difficulty with movement, speech and vision.

Intracerebral haemorrhage commonly affects cerebral lobes, the basal ganglia, the thalamus, the brain stem (predominantly the pons), and the cerebellum as a result of ruptured blood vessels affected by hypertension-related degenerative changes or cerebral amyloid angiopathy 1. Most bleeding in hypertension-related intracerebral haemorrhage is at or near the bifurcation of small penetrating arteries that originate from basilar arteries or the anterior, middle, or posterior cerebral arteries 17. Small artery branches of 50–700 μm in diameter often have multiple sites of rupture; some are associated with layers of platelet and fibrin aggregates. These lesions are characterized by breakage of elastic lamina, atrophy and fragmentation of smooth muscle, dissections, and granular or vesicular cellular degeneration 18. Severe atherosclerosis including lipid deposition can affect elderly patients in particular. Fibrinoid necrosis of the subendothelium with subsequent focal dilatations (micro aneurysms) leads to rupture in a small proportion of patients 17.

Post-partum intracerebral hemorrhage is a rare, but increasingly recognized, cause of hemorrhage in young women and is thought to be due to angiopathy in the post-partum period 19. The overall incidence of intracerebral hemorrhage in pregnancy and the post-partum period is 4.6-53/100,000 and is associated with significant maternal mortality 20.

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy is characterized by the deposition of amyloid-β peptide and degenerative changes (microaneurysm formation, concentric splitting, chronic inflammatory infiltrates, and fibrinoid necrosis) in the capillaries, arterioles, and small and medium sized arteries of the cerebral cortex, leptomeninges, and cerebellum 21. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy leads to sporadic intracerebral haemorrhage in elderly people, commonly associated with variations in the gene encoding apolipoprotein E, and a familial syndrome in young patients, typically associated with mutations in the gene encoding amyloid precursor protein 22. White-matter abnormalities (eg, leukoariosis) seem to increase the risk of both sporadic and familial intracerebral haemorrhage, suggesting a shared vascular pathogenesis 23.

Risk of intracerebral hemorrhage also is increased by the use of anticoagulants. Intracerebral haemorrhage associated with the taking of oral anticoagulants typically affects patients with vasculopathies related to either chronic hypertension or cerebral amyloid angiopathy, which might represent exacerbation of an existing risk of clinical and subclinical disease 24. In the United States, approximately 20% of patients with intracerebral hemorrhage use anticoagulants. Additional risk factors include greater age, male sex, cigarette smoking, and heavy use of alcohol 25, whereas high cholesterol is associated with a decreased risk of intracerebral hemorrhage 25.

It is still controversial whether statin therapy is a potential risk factor of intracerebral hemorrhage. Evidence suggests cholesterol lowering drugs result in hemorrhagic stroke 26. However, recent analyses of randomized controlled trials showed statin therapy are not associated with brain hemorrhage 27.

Intracerebral hemorrhage symptoms

The main symptoms of stroke can be remembered with the word FAST:

- Face – the face may have dropped on 1 side, the person may not be able to smile, or their mouth or eye may have dropped. Does one side of the face droop or is it numb? Ask the person to smile. Is the person’s smile uneven or lopsided?

- Arms – the person with suspected stroke may not be able to lift both arms and keep them there because of weakness or numbness in 1 arm. Is one arm weak or numb? Ask the person to raise both arms. Does one arm drift downward?

- Speech – their speech may be slurred or garbled, or the person may not be able to talk at all despite appearing to be awake; they may also have problems understanding what you’re saying to them. Is speech slurred? Is the person unable to speak or hard to understand? Ask the person to repeat a simple sentence.

- Time – it’s time to dial your local emergency number immediately if you see any of these signs or symptoms.

Additional symptoms of stroke

If someone shows any of these symptoms, call your local emergency medical services number immediately.

- Sudden NUMBNESS or weakness of face, arm, or leg, especially on one side of the body

- Sudden CONFUSION, trouble speaking or understanding speech

- Sudden TROUBLE SEEING in one or both eyes

- Sudden TROUBLE WALKING, dizziness, loss of balance or coordination

- Sudden SEVERE HEADACHE with no known cause.

Warning signs in posterior circulation strokes

Posterior circulations strokes (a stroke that occurs in the back part of the brain) occurs when a blood vessel in the back part of the brain is blocked causing the death of brain cells (called an infarction) in the area of the blocked blood vessel. This type of stroke can also be caused by a ruptured blood vessel in the back part of the brain. When this type of stroke happens several symptoms occur and they can be very different than the symptoms that occur in the blood circulation to the front part of the brain (called anterior circulation strokes).

Symptoms include:

- Vertigo, like the room, is spinning.

- Imbalance

- One-sided arm or leg weakness.

- Slurred speech or dysarthria

- Double vision or other vision problems

- A headache

- Nausea and or vomiting

If someone shows any of these signs and symptoms, immediately call your local emergency medical services number straight away.

Intracerebral hemorrhage diagnosis

To determine the most appropriate treatment for your stroke, your emergency team needs to evaluate the type of stroke you’re having and the areas of your brain affected by the stroke. They also need to rule out other possible causes of your symptoms, such as a brain tumor or a drug reaction. Your doctor may use several tests to determine your risk of stroke, including:

Physical examination. Your doctor will ask you or a family member what symptoms you’ve been having, when they started and what you were doing when they began. Your doctor then will evaluate whether these symptoms are still present. Your doctor will want to know what medications you take and whether you have experienced any head injuries. You’ll be asked about your personal and family history of heart disease, transient ischemic attack or stroke.

Your doctor will check your blood pressure and use a stethoscope to listen to your heart and to listen for a whooshing sound (bruit) over your neck (carotid) arteries, which may indicate atherosclerosis. Your doctor may also use an ophthalmoscope to check for signs of tiny cholesterol crystals or clots in the blood vessels at the back of your eyes.

- Blood tests. You may have several blood tests, which tell your care team how fast your blood clots, whether your blood sugar is abnormally high or low, whether critical blood chemicals are out of balance, or whether you may have an infection. Managing your blood’s clotting time and levels of sugar and other key chemicals will be part of your stroke care.

- Computerized tomography (CT) scan. A CT scan uses a series of X-rays to create a detailed image of your brain. A CT scan can show a hemorrhage, tumor, stroke and other conditions. Doctors may inject a dye into your bloodstream to view your blood vessels in your neck and brain in greater detail (computerized tomography angiography).

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). An MRI uses powerful radio waves and magnets to create a detailed view of your brain. An MRI can detect brain tissue damaged by an ischemic stroke and brain hemorrhages. Your doctor may inject a dye into a blood vessel to view the arteries and veins and highlight blood flow (magnetic resonance angiography, or magnetic resonance venography).

- Carotid ultrasound. In this test, sound waves create detailed images of the inside of the carotid arteries in your neck. This test shows buildup of fatty deposits (plaques) and blood flow in your carotid arteries.

- Cerebral angiogram. In this test, your doctor inserts a thin, flexible tube (catheter) through a small incision, usually in your groin, and guides it through your major arteries and into your carotid or vertebral artery. Then your doctor injects a dye into your blood vessels to make them visible under X-ray imaging. This procedure gives a detailed view of arteries in your brain and neck.

- Echocardiogram. An echocardiogram uses sound waves to create detailed images of your heart. An echocardiogram can find a source of clots in your heart that may have traveled from your heart to your brain and caused your stroke. You may have a transesophageal echocardiogram. In this test, your doctor inserts a flexible tube with a small device (transducer) attached into your throat and down into the tube that connects the back of your mouth to your stomach (esophagus). Because your esophagus is directly behind your heart, a transesophageal echocardiogram can create clear, detailed ultrasound images of your heart and any blood clots.

Intracerebral hemorrhage treatment

Emergency treatment of intracerebral hemorrhage or hemorrhagic stroke focuses on controlling your bleeding and reducing pressure in your brain. Surgery also may be performed to help reduce future risk.

Emergency measures

If you take warfarin (Coumadin) or anti-platelet drugs such as clopidogrel (Plavix) to prevent blood clots, you may be given drugs or transfusions of blood products to counteract the blood thinners’ effects. You may also be given drugs to lower pressure in your brain (intracranial pressure), lower your blood pressure, prevent vasospasm or prevent seizures.

Once the bleeding in your brain stops, treatment usually involves supportive medical care while your body absorbs the blood. Healing is similar to what happens while a bad bruise goes away. If the area of bleeding is large, your doctor may perform surgery to remove the blood and relieve pressure on your brain.

Surgical blood vessel repair

Surgery may be used to repair blood vessel abnormalities associated with hemorrhagic strokes. Your doctor may recommend one of these procedures after a stroke or if an aneurysm or arteriovenous malformation (AVM) or other type of vascular malformation caused your hemorrhagic stroke:

- Surgical clipping. A surgeon places a tiny clamp at the base of the aneurysm, to stop blood flow to it. This clamp can keep the aneurysm from bursting, or it can prevent re-bleeding of an aneurysm that has recently hemorrhaged.

- Coiling (endovascular embolization). In this procedure, a surgeon inserts a catheter into an artery in your groin and guides it to your brain using X-ray imaging. Your surgeon then guides tiny detachable coils into the aneurysm (aneurysm coiling). The coils fill the aneurysm, which blocks blood flow into the aneurysm and causes the blood to clot.

- Surgical arteriovenous malformation (AVM) removal. Surgeons may remove a smaller AVM if it’s located in an accessible area of your brain, to eliminate the risk of rupture and lower the risk of hemorrhagic stroke. However, it’s not always possible to remove an AVM if its removal would cause too large a reduction in brain function, or if it’s large or located deep within your brain.

- Intracranial bypass. In some unique circumstances, surgical bypass of intracranial blood vessels may be an option to treat poor blood flow to a region of the brain or complex vascular lesions, such as aneurysm repair.

- Stereotactic radiosurgery. Using multiple beams of highly focused radiation, stereotactic radiosurgery is an advanced minimally invasive treatment used to repair vascular malformations.

Intracerebral hemorrhage recovery

Following emergency treatment, stroke care focuses on helping you regain your strength, recover as much function as possible and return to independent living. The impact of your stroke depends on the area of the brain involved and the amount of tissue damaged.

If your stroke affected the right side of your brain, your movement and sensation on the left side of your body may be affected. If your stroke damaged the brain tissue on the left side of your brain, your movement and sensation on the right side of your body may be affected. Brain damage to the left side of your brain may cause speech and language disorders.

In addition, if you’ve had a stroke, you may have problems with breathing, swallowing, balancing and vision.

People who survive a stroke are often left with long-term problems caused by injury to their brain.

Some people need a long period of rehabilitation before they can recover their former independence, while many never fully recover and need support adjusting to living with the effects of their stroke.

Most stroke survivors receive treatment in a rehabilitation program. Your doctor will recommend the most rigorous therapy program you can handle based on your age, overall health and your degree of disability from your stroke. Your doctor will take into consideration your lifestyle, interests and priorities, and the availability of family members or other caregivers.

Your rehabilitation program may begin before you leave the hospital. It may continue in a rehabilitation unit of the same hospital, another rehabilitation unit or skilled nursing facility, an outpatient unit, or your home.

Every person’s stroke recovery is different. Depending on your condition, your treatment team may include:

- Doctor trained in brain conditions (neurologist)

- Rehabilitation doctor (physiatrist)

- Nurse

- Dietitian

- Physical therapist

- Occupational therapist

- Recreational therapist

- Speech therapist

- Social worker

- Case manager

- Psychologist or psychiatrist

- Chaplain

Psychological impact

Two of the most common psychological problems that can affect people after a stroke are:

- Depression – many people experience intense bouts of crying, and feel hopeless and withdrawn from social activities

- Anxiety – where people experience general feelings of fear and anxiety, sometimes punctuated by intense, uncontrolled feelings of anxiety (anxiety attacks)

Feelings of anger, frustration and bewilderment are also common.

You’ll receive a psychological assessment from a member of your healthcare team soon after your stroke to check if you’re experiencing any emotional problems.

Advice should be given to help deal with the psychological impact of stroke. This includes the impact on relationships with other family members and any sexual relationship.

There should also be a regular review of any problems of depression and anxiety, and psychological and emotional symptoms generally.

These problems may settle down over time, but if they are severe or last a long time, doctors can refer people for expert healthcare from a psychiatrist or clinical psychologist.

For some people, medicines and psychological therapies, such as counselling or cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), can help. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a therapy that aims to change the way you think about things to produce a more positive state of mind.

Cognitive impact

Cognitive is a term used by scientists to refer to the many processes and functions our brain uses to process information.

One or more cognitive functions can be disrupted by a stroke, including:

- Communication – both verbal and written

- Spatial awareness – having a natural awareness of where your body is in relation to your immediate environment

- Memory

- Concentration

- Executive function – the ability to plan, solve problems and reason about situations

- Praxis – the ability to carry out skilled physical activities, such as getting dressed or making a cup of tea

As part of your treatment, each one of your cognitive functions will be assessed and a treatment and rehabilitation plan will be created.

You can be taught a wide range of techniques that can help you relearn disrupted cognitive functions, such as recovering your communication skills through speech and language therapy.

There are many ways to compensate for any loss of cognitive function, such as using memory aids, diaries and routines to help plan daily tasks.

Most cognitive functions will return after time and rehabilitation, but you may find they don’t return to the way they were before.

The damage a stroke causes to your brain also increases the risk of developing vascular dementia. This may happen immediately after a stroke or may develop some time after the stroke occurred.

Movement problems

Strokes can cause weakness or paralysis on one side of the body, and can result in problems with co-ordination and balance.

Many people also experience extreme tiredness (fatigue) in the first few weeks after a stroke, and may also have difficulty sleeping, making them even more tired.

As part of your rehabilitation, you should be seen by a physiotherapist, who will assess the extent of any physical disability before drawing up a treatment plan.

Physiotherapy will often involve several sessions a week, focusing on areas such as exercises to improve your muscle strength and overcome any walking difficulties.

The physiotherapist will work with you by setting goals. At first, these may be simple goals, such as picking up an object. As your condition improves, more demanding long-term goals, such as standing or walking, will be set.

A careworker or carer, such as a member of your family, will be encouraged to become involved in your physiotherapy. The physiotherapist can teach you both simple exercises you can carry out at home.

If you have problems with movement and certain activities, such as getting washed and dressed, you may also receive help from an occupational therapist. They can find ways to manage any difficulties.

Occupational therapy may involve adapting your home or using equipment to make everyday activities easier, and finding alternative ways of carrying out tasks you have problems with.

Communication problems

After having a stroke, many people experience problems with speaking and understanding, as well as reading and writing.

If the parts of the brain responsible for language are damaged, this is called aphasia, or dysphasia. If there is weakness in the muscles involved in speech as a result of brain damage, this is known as dysarthria.

You should see a speech and language therapist as soon as possible for an assessment and to start therapy to help you with your communication.

This may involve:

- exercises to improve your control over your speech muscles

- using communication aids – such as letter charts and electronic aids

- using alternative methods of communication – such as gestures or writing

Swallowing problems

The damage caused by a stroke can interrupt your normal swallowing reflex, making it possible for small particles of food to enter your windpipe.

Problems with swallowing are known as dysphagia. Dysphagia can lead to damage to your lungs, which can trigger a lung infection (pneumonia).

You may need to be fed using a feeding tube during the initial phases of your recovery to prevent any complications from dysphagia.

The tube is usually put into your nose and passed into your stomach (nasogastric tube), or it may be directly connected to your stomach in a minor surgical procedure carried out using local anesthetic (percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy, or PEG).

In the long term, you’ll usually see a speech and language therapist several times a week for treatment to manage your swallowing problems.

Treatment may involve tips to make swallowing easier, such as taking smaller bites of food and advice on posture, and exercises to improve control of the muscles involved in swallowing.

Visual problems

Stroke can sometimes damage the parts of the brain that receive, process and interpret information sent by the eyes.

This can result in losing half the field of vision – for example, only being able to see the left- or right hand side of what’s in front of you.

Strokes can also affect the control of the movement of the eye muscles. This can cause double vision.

If you have any problems with your vision after a stroke, you’ll be referred to an eye specialist called an orthoptist, who can assess your vision and suggest possible treatments.

For example, if you’ve lost part of your field of vision, you may be offered eye movement therapy. This involves exercises to help you look to the side with the reduced vision.

You may also be given advice about particular ways to perform tasks that can be difficult if your vision is reduced on one side, such as getting dressed.

Bladder and bowel control

Some strokes damage the part of the brain that controls bladder and bowel movements. This can result in urinary incontinence and difficulty with bowel control.

Some people may regain bladder and bowel control quite quickly, but if you still have problems after leaving hospital, help is available from the hospital, your GP, and specialist continence advisers.

Don’t be embarrassed – seek advice if you have a problem, as there are lots of treatments that can help.

These include:

- bladder retraining exercises

- medications

- pelvic floor exercises

- using incontinence products

Sex after a stroke

Having sex won’t put you at higher risk of having a stroke. There’s no guarantee you won’t have another stroke, but there’s no reason why it should happen while you’re having sex.

Even if you’ve been left with a severe disability, you can experiment with different positions and find new ways of being intimate with your partner.

Be aware that some medications can reduce your sex drive (libido), so make sure your doctor knows if you have a problem – there may be other medicines that can help.

Some men may experience erectile dysfunction after having a stroke. Speak to your GP or rehabilitation team if this is the case, as there are a number of treatments available that can help.

Driving after a stroke

If you’ve had a stroke or TIA, you can’t drive for one month. Whether you can return to driving depends on what long-term disabilities you may have and the type of vehicle you drive.

It’s often not physical problems that can make driving dangerous, but problems with concentration, vision, reaction time and awareness that can develop after a stroke.

Your doctor can advise you on whether you can start driving again a month after your stroke, or whether you need further assessment at a mobility center.

Preventing further strokes

If you’ve had a stroke, your chances of having another one are significantly increased.

You’ll usually require long-term treatment with medications aimed at improving the underlying risk factors for your stroke.

For example:

- medication – to help lower your blood pressure

- anticoagulants or antiplatelets – to reduce your risk of blood clots

- statins – to lower your cholesterol levels

You’ll also be encouraged to make lifestyle changes to improve your general health and lower your stroke risk, such as:

- eating a healthy diet

- exercising regularly

- stopping smoking if you smoke

- cutting down on the amount of alcohol you drink

Caring for someone who’s had a stroke

There are many ways you can provide support to a friend or relative who’s had a stroke to speed up their rehabilitation process.

These include:

- helping them practise physiotherapy exercises in between their sessions with the physiotherapist

- providing emotional support and reassurance their condition will improve with time

- helping motivate them to reach their long-term goals

- adapting to any needs they may have, such as speaking slowly if they have communication problems

Caring for somebody after a stroke can be a frustrating and lonely experience. The advice outlined below may help.

Be prepared for changed behavior

Someone who’s had a stroke can often seem as though they’ve had a change in personality and appear to act irrationally at times. This is the result of the psychological and cognitive impact of a stroke.

They may become angry or resentful towards you. Upsetting as it may be, try not to take it personally.

It’s important to remember they’ll often start to return to their old self as their rehabilitation and recovery progresses.

Try to remain patient and positive

Rehabilitation can be a slow and frustrating process, and there will be periods of time when it appears little progress has been made.

Encouraging and praising any progress, no matter how small it may appear, can help motivate someone who’s had a stroke to achieve their long-term goals.

Make time for yourself

If you’re caring for someone who’s had a stroke, it’s important not to neglect your own physical and psychological wellbeing. Socializing with friends or pursuing leisure interests will help you cope better with the situation.

Ask for help

There are a wide range of support services and resources available for people recovering from strokes, and their families and carers. This ranges from equipment that can help with mobility, to psychological support for carers and families.

The hospital staff involved with the rehabilitation process can provide advice and relevant contact information.

- Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Qureshi AI, Tuhrim S, Broderick JP, Batjer HH, Hondo H, Hanley DF. N Engl J Med. 2001 May 10; 344(19):1450-60.[↩][↩][↩]

- The incidence of deep and lobar intracerebral hemorrhage in whites, blacks, and Hispanics. Labovitz DL, Halim A, Boden-Albala B, Hauser WA, Sacco RL. Neurology. 2005 Aug 23; 65(4):518-22.[↩]

- Comparable studies of the incidence of stroke and its pathological types: results from an international collaboration. International Stroke Incidence Collaboration. Sudlow CL, Warlow CP. Stroke. 1997 Mar; 28(3):491-9.[↩]

- Qureshi AI, Mendelow AD, Hanley DF. Intracerebral haemorrhage. Lancet. 2009;373(9675):1632–1644. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60371-8 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3138486[↩][↩]

- Hemorrhagic Stroke (Bleeds). https://www.stroke.org/en/about-stroke/types-of-stroke/hemorrhagic-strokes-bleeds[↩]

- The clinical management of acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Aiyagari V. Expert Rev Neurother. 2015; 15(12):1421-32.[↩][↩]

- Intracerebral haemorrhage. Qureshi AI, Mendelow AD, Hanley DF. Lancet. 2009 May 9; 373(9675):1632-44.[↩]

- Changes in cost and outcome among US patients with stroke hospitalized in 1990 to 1991 and those hospitalized in 2000 to 2001. Qureshi AI, Suri MF, Nasar A, Kirmani JF, Ezzeddine MA, Divani AA, Giles WH. Stroke. 2007 Jul; 38(7):2180-4.[↩]

- Stroke epidemiology: a review of population-based studies of incidence, prevalence, and case-fatality in the late 20th century. Feigin VL, Lawes CM, Bennett DA, Anderson CS. Lancet Neurol. 2003 Jan; 2(1):43-53.[↩]

- Incidence and trends of stroke and its subtypes in China: results from three large cities. Jiang B, Wang WZ, Chen H, Hong Z, Yang QD, Wu SP, Du XL, Bao QJ. Stroke. 2006 Jan; 37(1):63-8.[↩]

- Change in stroke incidence, mortality, case-fatality, severity, and risk factors in Oxfordshire, UK from 1981 to 2004 (Oxford Vascular Study). Rothwell PM, Coull AJ, Giles MF, Howard SC, Silver LE, Bull LM, Gutnikov SA, Edwards P, Mant D, Sackley CM, Farmer A, Sandercock PA, Dennis MS, Warlow CP, Bamford JM, Anslow P, Oxford Vascular Study. Lancet. 2004 Jun 12; 363(9425):1925-33.[↩]

- Role of cerebral amyloid angiopathy in intracerebral hemorrhage in hypertensive patients. Ritter MA, Droste DW, Hegedüs K, Szepesi R, Nabavi DG, Csiba L, Ringelstein EB. Neurology. 2005 Apr 12; 64(7):1233-7.[↩]

- Xi G, Strahle J, Hua Y, Keep RF. Progress in translational research on intracerebral hemorrhage: is there an end in sight?. Prog Neurobiol. 2014;115:45–63. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.09.007 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3961535[↩]

- Intracerebral hemorrhage in young people: analysis of risk factors, location, causes, and prognosis. Ruíz-Sandoval JL, Cantú C, Barinagarrementeria F. Stroke. 1999 Mar; 30(3):537-41.[↩]

- Apolipoprotein E genotype and the risk of recurrent lobar intracerebral hemorrhage. O’Donnell HC, Rosand J, Knudsen KA, Furie KL, Segal AZ, Chiu RI, Ikeda D, Greenberg SM. N Engl J Med. 2000 Jan 27; 342(4):240-5.[↩]

- What is an Arteriovenous Malformation. https://www.stroke.org/en/about-stroke/types-of-stroke/hemorrhagic-strokes-bleeds/what-is-an-arteriovenous-malformation[↩]

- Electron microscopic studies of ruptured arteries in hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage. Takebayashi S, Kaneko M. Stroke. 1983 Jan-Feb; 14(1):28-36.[↩][↩]

- Arterial dissections of penetrating cerebral arteries causing hypertension-induced cerebral hemorrhage. Mizutani T, Kojima H, Miki Y. J Neurosurg. 2000 Nov; 93(5):859-62.[↩]

- Intracerebral hemorrhage in pregnancy: frequency, risk factors, and outcome. Bateman BT, Schumacher HC, Bushnell CD, Pile-Spellman J, Simpson LL, Sacco RL, Berman MF. Neurology. 2006 Aug 8; 67(3):424-9.[↩]

- Haemorrhagic strokes in pregnancy and puerperium. Khan M, Wasay M. Int J Stroke. 2013 Jun; 8(4):265-72.[↩]

- Warfarin-associated hemorrhage and cerebral amyloid angiopathy: a genetic and pathologic study. Rosand J, Hylek EM, O’Donnell HC, Greenberg SM. Neurology. 2000 Oct 10; 55(7):947-51.[↩]

- The genetic architecture of intracerebral hemorrhage. Rost NS, Greenberg SM, Rosand J. Stroke. 2008 Jul; 39(7):2166-73.[↩]

- White matter lesions, cognition, and recurrent hemorrhage in lobar intracerebral hemorrhage. Smith EE, Gurol ME, Eng JA, Engel CR, Nguyen TN, Rosand J, Greenberg SM. Neurology. 2004 Nov 9; 63(9):1606-12.[↩]

- What causes intracerebral hemorrhage during warfarin therapy? Hart RG. Neurology. 2000 Oct 10; 55(7):907-8.[↩]

- Risk factors for intracerebral hemorrhage in the general population: a systematic review. Ariesen MJ, Claus SP, Rinkel GJ, Algra A. Stroke. 2003 Aug; 34(8):2060-5.[↩][↩]

- Hemorrhagic stroke in the Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels study. Goldstein MR, Mascitelli L, Pezzetta F. Neurology. 2009 Apr 21; 72(16):1448; author reply 1448-9.[↩]

- Statin therapy and the risk of intracerebral hemorrhage: a meta-analysis of 31 randomized controlled trials. McKinney JS, Kostis WJ. Stroke. 2012 Aug; 43(8):2149-56.[↩]