Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma also known as NHL or just lymphoma, is a cancer that starts when a type of white blood cell, called lymphocyte (T cell or B cell), becomes abnormal. About 85-90 percent of NHL cases start in the B cells 1. In non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, lymphocytes undergo a malignant (cancerous) change and then multiplies, eventually crowding out healthy cells and creating tumors. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma generally develop in the lymph nodes or in lymphatic tissue found in organs such as the stomach, intestines or skin. Furthermore, these abnormal cells can spread to almost any other part of the body. In some cases, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma involves blood and the bone marrow (the spongy tissue in the hollow, central cavity of bones, where blood cell formation occurs). Lymphoma cells may develop in just one place or in many sites in the body. Most of the time, doctors don’t know why a person gets non-Hodgkin lymphoma. You are at increased risk if you have a weakened immune system or have certain types of infections.

More than 60 specific non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) subtypes have been identified and assigned names, so classifying it can be quite confusing (even for doctors). Several different systems have been used, but the most recent system is the World Health Organization (WHO) classification 2. The Revised European American Lymphoma and World Health Organization (REAL/WHO) classification of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma categorizes non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma subtypes by the characteristics of the lymphoma cells, including their appearance, the presence of proteins on the surface of the cells and their genetic features. One way that non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma subtypes are classified is by cell type. Some non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma subtypes, such as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and follicular lymphoma (FL), involve lymphocytes called “B cells.” Other subtypes, such as peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL) and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), involve lymphocytes called “T cells” or “natural killer (NK) cells.”

Specialists further classify the non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma subtypes according to the rate of disease progression, either fast growing (aggressive) or slow growing (indolent). Aggressive lymphoma subtypes also called “high-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma”, account for about 60 percent of all non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma cases. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is the most common aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma subtype. Slow-growing (indolent) subtypes account for about 40 percent of all non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma cases. Follicular lymphoma (FL) is the most common subtype of indolent non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. When indolent lymphomas are first diagnosed, patients have fewer signs and symptoms than patients with aggressive lymphoma subtypes. Whether the diagnosed subtype is aggressive or indolent determines the appropriate treatment, so getting an accurate diagnosis is very important. In some cases, indolent forms of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma later transform into an aggressive form of the disease.

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) is one of the most common cancers in the United States, accounting for about 4.2% of all cancers. The American Cancer Society’s most recent estimates for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma are for 2022 3:

- New cases: About 80,470 people (44,120 males and 36,350 females) will be diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. This includes both adults and children.

- Deaths: About 20,250 people will die from non-Hodgkin lymphoma (11,700males and 8,550 females).

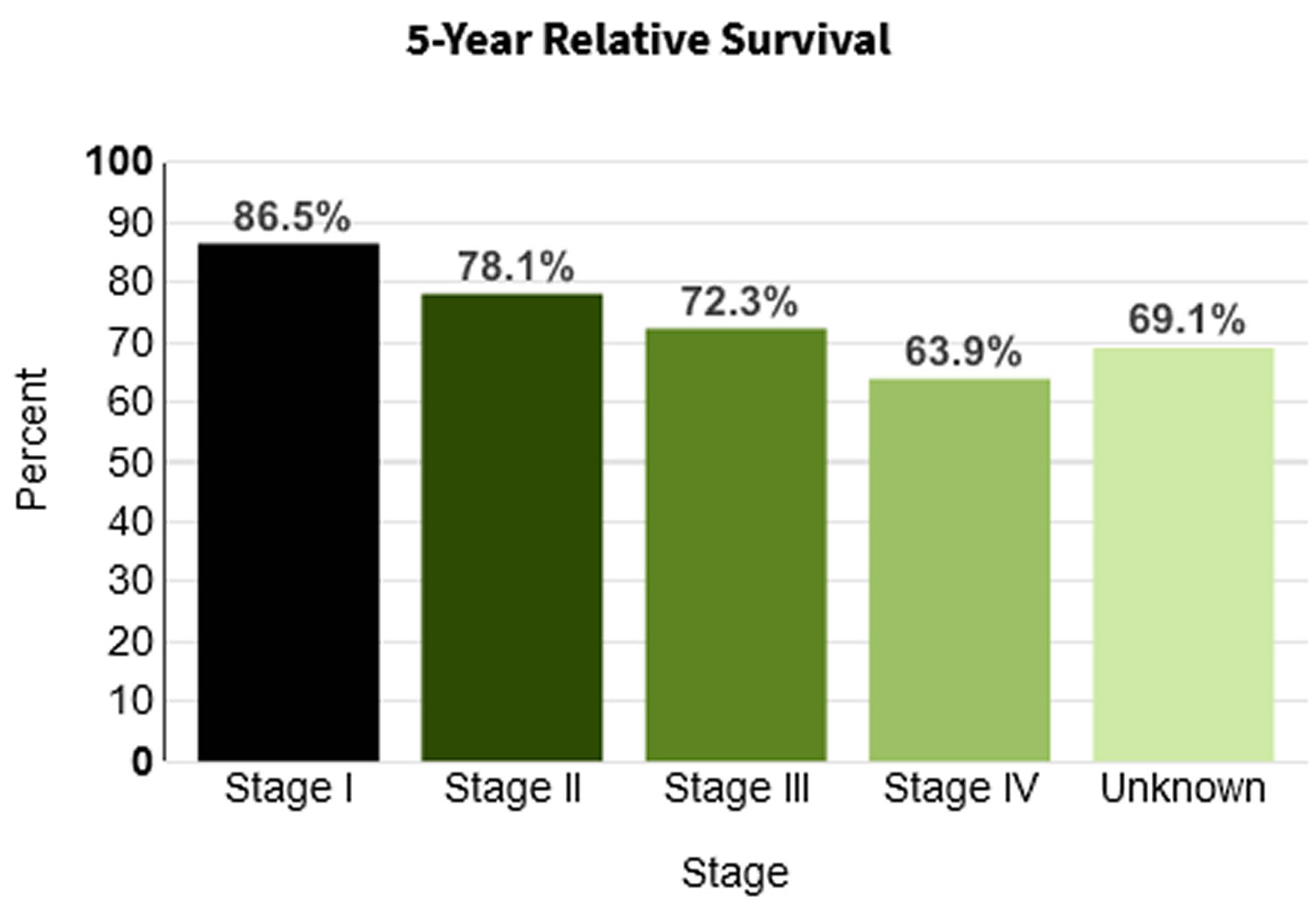

- 5-Year Relative Survival: 73.8%. Relative survival is an estimate of the percentage of patients who would be expected to survive the effects of their cancer. It excludes the risk of dying from other causes. Because survival statistics are based on large groups of people, they cannot be used to predict exactly what will happen to an individual patient. No two patients are entirely alike, and treatment and responses to treatment can vary greatly.

- Percentage of All Cancer Deaths: 3.3%.

- Rate of New Cases and Deaths per 100,000: The rate of new cases of non-Hodgkin lymphoma was 19.0 per 100,000 men and women per year. The death rate was 5.3 per 100,000 men and women per year. These rates are age-adjusted and based on 2015–2019 cases and deaths.

- Lifetime Risk of Developing Cancer: Approximately 2.1 percent of men and women will be diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma at some point during their lifetime, based on 2017–2019 data.

- In 2019, there were an estimated 763,400 people living with non-Hodgkin lymphoma in the United States.

The average American’s risk of developing non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma during a man’s lifetime is about 1 in 42; for a woman, the risk is about 1 in 52 4. But each person’s risk can be affected by a number of risk factors.

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma can occur at any age. In fact, it is one of the more common cancers among children, teens, and young adults. Still, the risk of developing non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma increases throughout life, and more than half of patients are 65 or older at the time of diagnosis. The aging of the American population is likely to lead to an increase in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma cases during the coming years.

Treatment for non-Hodgkin lymphoma depends on which type it is, so it’s important for doctors to find out the exact type of lymphoma you have. The type of lymphoma depends on what type of lymphocyte is affected (B cells or T cells), how mature the cells are when they become cancerous, and other factors.

The prognosis and treatment approach for different non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma subtypes are influenced by findings from studying the diseased cells and tissues under a microscope, so biopsy samples should be examined by a hematopathologist (a doctor who specializes in the diagnosis of blood disorders and blood cancers).

The Lymphatic System

To understand what lymphoma is, it helps to know about the lymph system (also known as the lymphatic system). The lymph system is part of the immune system, which helps fight infections and some other diseases. The lymphatic system plays a role in:

- fighting bacteria and other infections

- destroying old or abnormal cells, such as cancer cells

The lymphatic system also helps the flow of fluids in the body.

The lymph system is made up mainly of cells called lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell. There are 3 main types of lymphocytes:

- B lymphocytes (B cells): B cells make proteins called antibodies to help protect the body from germs (bacteria and viruses).

- T lymphocytes (T cells): There are several types of T cells. Some T cells destroy germs or abnormal cells in the body. Other T cells help boost or slow the activity of other immune system cells.

- Natural killer (NK) cells, which attack virus-infected cells or tumor cells

The lymphatic system is a vast collection of cells and biochemicals that travel in lymphatic vessels, and the organs and glands that produce them. The lymphatic system includes a network of vessels (like the arteries and veins that carry blood) that assist in circulating body fluids (a colorless liquid called lymph), so it is closely associated with your cardiovascular system. Lymphatic vessels transport excess fluid away from interstitial spaces in most tissues and return it to the bloodstream (Figure 3). This fluid carries food to the cells and bathes the body tissues to form tissue fluid. The fluid then collects waste products, bacteria, and damaged cells. It also collects any cancer cells if these are present. This fluid then drains into the lymph vessels. Without the lymphatic system, this fluid would accumulate in tissue spaces. Special lymphatic capillaries, called lacteals, are located in the lining of the small intestine. They absorb digested fats and transport them to the venous circulation.

The lymphatic system is a system of thin tubes and lymph nodes that run throughout the body. Lymph nodes are bean shaped glands. The thin tubes are called lymph vessels or lymphatic vessels. Tissue fluid called lymph circulates around the body in these vessels and flows through the lymph nodes.

The lymph system is an important part of your immune system. It plays a role in fighting bacteria and other infections and destroying old or abnormal cells, such as cancer cells.

The major sites of lymphoid tissue are:

- Lymph nodes: Lymph nodes are bean-sized collections of lymphocytes and other immune system cells throughout the body, including inside the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. They are connected to each other by a system of lymphatic vessels.

- Spleen: The spleen is an organ under the lower ribs on your left side. The spleen makes lymphocytes and other immune system cells. It also stores healthy blood cells and filters out damaged blood cells, bacteria, and cell waste.

- Bone marrow: The bone marrow is the spongy tissue inside certain bones. New blood cells (including some lymphocytes) are made there.

- Thymus: The thymus is a small organ behind the upper part of the breastbone and in front of the heart. Thymus is an organ in which T lymphocytes mature and multiply.

- Adenoids and tonsils: These are collections of lymphoid tissue in the back of your throat. They help make antibodies against germs that are breathed in or swallowed.

- Digestive tract: The stomach, intestines, and many other organs also have lymph tissue.

The lymphatic system has a second major function— it enables you to live in a world with different types of organisms. Some of them live in or on the human body and in some circumstances may cause infectious diseases. Cells and biochemicals of the lymphatic system launch both generalized and targeted attacks against “foreign” particles, enabling the body to destroy infectious agents. This immunity against disease also protects against toxins and cancer cells. When the immune response is abnormal, persistent infection, cancer, allergies, and autoimmune disorders may result.

The larger lymphatic vessels lead to specialized organs called lymph nodes. After leaving the lymph nodes, the vessels merge to form still larger lymphatic trunks.

Figure 1. Locations of major lymph nodes

Figure 2. Functions of lymph nodes in the lymphatic system

Figure 3. Schematic representation of lymphatic vessels transporting fluid from interstitial spaces to the bloodstream. Depending on its origin, lymph enters the right or left subclavian vein.

Types of Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma

More than 60 specific non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) subtypes have been identified and assigned names, so classifying it can be quite confusing (even for doctors). Several different systems have been used, but the most recent system is the World Health Organization (WHO) classification.

The WHO system groups lymphomas based on:

- The type of lymphocyte the lymphoma starts in

- How the lymphoma looks under a microscope

- The chromosome features of the lymphoma cells

- The presence of certain proteins on the surface of the cells

The more common types of lymphoma are listed below according to whether they start in B lymphocytes (B cells) or T lymphocytes (T cells) with B-cell lymphomas being the most common. Some rarer forms of non-Hodgkin lymphoma are not listed here.

Specialists further classify the non-Hodgkin lymphoma subtypes according to the rate of disease progression, either fast growing (aggressive) or slow growing (indolent).

- Indolent non-Hodgkin lymphomas also called “low-grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma”, are slow-moving and tend to grow more slowly and have fewer signs and symptoms when first diagnosed. Some indolent lymphomas might not need to be treated right away, but can be watched closely instead. Slow-growing (indolent) subtypes account for about 40 percent of all non-Hodgkin lymphoma cases. The most common type of indolent lymphoma in the United States is follicular lymphoma (FL).

- Aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphomas also called “high-grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma”, grow and spread quickly, and usually need to be treated right away. Aggressive lymphoma subtypes account for about 60 percent of all non-Hodgkin lymphoma cases. The most common type of aggressive lymphoma in the United States is diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

- Some types of lymphoma, like mantle cell lymphoma, don’t fit neatly into either of these categories.

When indolent lymphomas are first diagnosed, patients have fewer signs and symptoms than patients with aggressive lymphoma subtypes. Whether the diagnosed subtype is aggressive or indolent lymphoma determines the appropriate treatment, so getting an accurate diagnosis is very important. In some cases, indolent forms of non-Hodgkin lymphoma later transform into an aggressive form of the disease 5.

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma Subtypes

Mature B-cell lymphomas (about 85%-90% of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma cases)

- Aggressive lymphomas (high-grade non-Hodgkin lymphomas)

- Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) (31%)

- Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) (can present as aggressive or indolent) (6%)

- Lymphoblastic lymphoma (2%)

- Burkitt lymphoma (BL) (2%)

- Primary mediastinal (thymic) large B-cell lymphoma (PMBCL) (2%)

- Transformed follicular and transformed mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas

- High-grade B-cell lymphoma with double or triple hits (HBL)

- Primary cutaneous DLBCL, leg type

- Primary DLBCL of the central nervous system

- Primary central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma

- Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-associated lymphoma

- Indolent lymphomas

- Follicular lymphoma (FL) (22%)

- Marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) (8%)

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small-cell lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL) (6%)

- Gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma (5%)

- Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (1%)

- Waldenström macroglobulinemia (WM)

- Nodal marginal zone lymphoma (NMZL) (1%)

- Splenic marginal zone lymphoma (SMZL)

Mature T-cell and natural killer (NK)-cell lymphomas (about 10%-15% of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma cases)

- Aggressive lymphomas (high-grade non-Hodgkin lymphomas)

- Peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL), not otherwise specified (6%)

- Systemic anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL) (2%)

- Lymphoblastic lymphoma (2%)

- Hepatosplenic gamma/delta T-cell lymphoma

- Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (SPTCL)

- Enteropathy-type intestinal T-cell lymphoma

- Primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma

- Indolent lymphomas

- Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) (4%)

- Mycosis fungoides (MF)

- Sézary syndrome (SS)

- Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL)

- Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma

- Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma (ENK/TCL), nasal type

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma Grades

Doctors sometimes put non-Hodgkin lymphoma into 2 groups, depending on how quickly they are likely to grow and spread. The 2 groups are low grade and high grade. The different grades of non-Hodgkin lymphoma are treated in slightly different ways.

- Low grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma also called indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma tends to grow very slowly. Follicular lymphoma is the most common type of low grade lymphoma. Other types of non Hodgkin’s lymphomas include:

- Mantle cell lymphoma

- Marginal zone lymphoma

- Small lymphocytic lymphoma

- Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma

- Skin lymphoma

- Over time, low grade lymphomas may change into a high grade type lymphoma.

- High grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma also called aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma tends to grow more quickly than low grade lymphomas. Because they grow quickly your doctor might call your lymphoma an aggressive type. Diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common type of high grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Other types of high grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma are:

- Burkitt lymphoma

- Peripheral T cell lymphoma

- Lymphoblastic lymphoma

- Blastic NK cell lymphoma

- Enteropathy associated T cell lymphoma (EATL)

- Hepatosplenic gamma delta T cell lymphoma

- Treatment related T cell lymphoma

- Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL)

B-cell lymphomas

B-cell lymphomas make up most (about 85%) of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in the United States. These are types of lymphoma that affect B lymphocytes. The most common types of B-cell lymphomas are listed below.

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL)

This is the most common type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in the United States, accounting for about 1 out of every 3 lymphomas. The lymphoma cells look fairly large when seen with a microscope.

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) can affect people of any age, but it occurs mostly in older people. The average age at the time of diagnosis is mid-60s. It usually starts as a quickly growing mass in a lymph node deep inside the body, such as in the chest or abdomen, or in a lymph node you can feel, such as in the neck or armpit. It can also start in other areas such as the intestines, bones, or even the brain or spinal cord.

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) tends to be a fast-growing (aggressive) lymphoma, but it often responds well to treatment. Overall, about 3 out of 4 people will have no signs of disease after the initial treatment, and many are cured.

A common subtype of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma. This type of lymphoma occurs mostly in young women. It starts in the mediastinum (the area in the middle of the chest behind the breastbone). It can grow quite large and can cause trouble breathing because it often presses on the windpipe (trachea) leading into the lungs. It can also block the superior vena cava (the large vein that returns blood to the heart from the arms and head), which can make the arms and face swell. This is a fast-growing lymphoma, but it usually responds well to treatment.

There are several other subtypes of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, but these are rare.

Follicular lymphoma

About 1 out of 5 lymphomas in the United States is a follicular lymphoma. This is usually a slow-growing (indolent) lymphoma, although some follicular lymphomas can grow quickly.

The average age for people with follicular lymphoma is about 60. It’s rare in very young people. Usually, follicular lymphoma occurs in many lymph node sites throughout the body, as well as in the bone marrow.

Follicular lymphomas often respond well to treatment, but they are hard to cure. These lymphomas may not need to be treated when they are first diagnosed. Instead, treatment may be delayed until the lymphoma starts causing problems. Over time, some follicular lymphomas turn into a fast-growing diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) /small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL)

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) are closely related diseases. In fact, many doctors consider them different versions of the same disease. The same type of cancer cell (known as a small lymphocyte) is seen in both chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL). The only difference is where the cancer cells are found. In chronic lymphocytic leukemia, most of the cancer cells are in the blood and bone marrow. In small lymphocytic lymphoma, the cancer cells are mainly in the lymph nodes and spleen.

Both chronic lymphocytic leukemia and small lymphocytic lymphoma are usually slow-growing (indolent) diseases, although chronic lymphocytic leukemia, which is much more common, tends to grow more slowly. Treatment is the same for chronic lymphocytic leukemia and small lymphocytic lymphoma. They are usually not curable with standard treatments, but many people can live a long time (even decades) with them. Sometimes, these can turn into a more aggressive (fast-growing) type of lymphoma over time.

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL)

About 5% of lymphomas are mantle cell lymphomas (MCL). Mantle cell lymphoma is much more common in men than in women, and it most often appears in people older than 60. When mantle cell lymphoma is diagnosed, it is usually widespread in the lymph nodes, bone marrow, and often the spleen.

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) can be challenging to treat. It tends to grow faster than indolent (slow-growing) lymphomas, but it doesn’t usually respond to treatment as well as aggressive (fast-growing) lymphomas. But newer treatments might offer a better chance for long-term survival for patients now being diagnosed.

Marginal zone lymphomas

Marginal zone lymphomas account for about 5% to 10% of lymphomas. They tend to be slow-growing (indolent). The cells in these lymphomas look small under the microscope. There are 3 main types of marginal zone lymphomas:

- Extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma, also known as mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma: This is the most common type of marginal zone lymphoma. It starts in places other than the lymph nodes (extranodal). Most MALT lymphomas start in the stomach and are linked to infection by Helicobacter pylori (the bacteria that causes many stomach ulcers). MALT lymphoma might also start in the lung, skin, thyroid, salivary glands, or tissues surrounding the eye. Usually the lymphoma stays in the area where it begins and is not widespread. Many of these other MALT lymphomas have also been linked to infections with bacteria or viruses. The average age of people with MALT lymphoma at the time of diagnosis is about 60. This lymphoma tends to grow slowly and is often curable if found early. Doctors often use antibiotics as the first treatment for MALT lymphoma of the stomach, because treating the Helicobacter pylori infection often cures the lymphoma.

- Nodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma: This is a rare disease, found mainly in older women. It starts and usually stays in the lymph nodes, although lymphoma cells can also sometimes be found in the bone marrow. Nodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma tends to be slow-growing (although not usually as slow as MALT lymphoma), and is often curable if found early.

- Splenic marginal zone B-cell lymphoma: This is a rare lymphoma. Most often the lymphoma is found only in the spleen and bone marrow. Splenic marginal zone B-cell lymphoma is most common in older men, and often causes fatigue and discomfort due to an enlarged spleen. Because the disease is slow-growing, it might not need to be treated unless the symptoms become troublesome. This type of lymphoma has been linked to infection with the hepatitis C virus. Sometimes treating the hepatitis C virus can also treat this lymphoma.

Burkitt lymphoma

Burkitt lymphoma is a fast-growing lymphoma is named after the doctor who first described this disease in African children and young adults. Burkitt lymphoma makes up about 1% to 2% of all lymphomas. It is rare in adults, but is more common in children. It’s also much more common in males than in females.

The cells in Burkitt lymphoma are medium-sized. A similar kind of lymphoma, Burkitt-like lymphoma, has slightly larger cells. Because it is hard to tell these lymphomas apart, the WHO classification combines them.

Different varieties of Burkitt lymphoma are seen in different parts of the world:

- In the African (or endemic) variety, Burkitt lymphoma often starts as a tumor of the jaw or other facial bones. It is often linked to infection with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV, which can also cause infectious mononucleosis or “mono”). This type of Burkitt lymphoma is rare in the United States.

- In the type seen more often in the United States, the lymphoma usually starts in the abdomen (belly), where it forms a large tumor. It can also start in the ovaries, testicles, or other organs, and can spread to the brain and spinal fluid. It is not usually linked to EBV infection.

- Another type (immunodeficiency-associated) of Burkitt lymphoma is associated with immune system problems, such as in people with HIV or AIDS or who have had an organ transplant.

Burkitt lymphoma grows very quickly, so it needs to be treated right away. But more than half of patients can be cured by intensive chemotherapy.

Lymphoplasmacytic Lymphoma and Waldenström Macroglobulinemia

Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma and Waldenström macroglobulinemia are both slow-growing types of lymphoma that originate in a B-lymphocyte precursor. Waldenström macroglobulinemia is a type of lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma. It is when a monoclonal immunoglobulin M (IgM) protein is identified in the blood, along with lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma in the bone marrow, that the disease is referred to as Waldenström macroglobulinemia. The immunoglobulin M (IgM) protein makes the blood thicker.

Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma and Waldenström macroglobulinemia is a slow-growing lymphoma is not common, accounting for only 1% to 2% of lymphomas. Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia) is rare, with an incidence rate of about 3 cases per million people per year in the United States. About 1,000 to 1,500 people are diagnosed with lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia) each year in the United States. Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia) is more common in men than it is in women and it is much more common among Whites than African Americans.

There are few cases of lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia) in younger people, but the chance of developing this disease goes up as people get older. The average age of people when they are diagnosed with lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia) is 70.

Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia) cells make large amounts of a certain type of antibody (immunoglobulin M, or IgM), which is known as a macroglobulin. Each antibody (protein) made by the lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia) cells is the same, so it is called a monoclonal protein or just an M protein. The buildup of this M protein in the body can lead to many of the symptoms of Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia, including excess bleeding, problems with vision, and nervous system problems.

The lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia) cells grow mainly in the bone marrow, where they can crowd out the normal cells that make the different types of blood cells. This can lead to low levels of red blood cells (called anemia), which can make people feel tired and weak. It can also cause low numbers of white blood cells, which makes it hard for the body to fight infection. The numbers of platelets in the blood can also drop, leading to increased bleeding and bruising.

Hairy cell leukemia

Despite the name, hairy cell leukemia (HCL) is sometimes considered to be a type of lymphoma. Hairy cell leukemia (HCL) is rare – about 700 people in the United States are diagnosed with it each year. Men are much more likely to get hairy cell leukemia (HCL) than women, and the average age at diagnosis is around 50.

Hairy cell leukemia (HCL) cells are small B lymphocytes with projections coming off them that give them a “hairy” appearance. They are typically found in the bone marrow and spleen and in the blood.

Hairy cell leukemia is slow-growing, and some people may never need treatment. An enlarging spleen or low blood cell counts (due to cancer cells invading the bone marrow) are the usual reasons to begin treatment. If treatment is needed, it’s usually very effective.

Primary central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma

This lymphoma involves the brain or spinal cord (the central nervous system, or CNS). The lymphoma is also sometimes found in tissues around the spinal cord or the eye. Over time, it tends to become widespread in the central nervous system.

Primary CNS lymphoma is rare overall, but it’s more common in older people and in people with immune system problems, such as those who have had an organ transplant or who have AIDS. Most people develop headaches and confusion. They can also have vision problems; weakness or altered sensation in the face, arms, or legs; and in some cases, seizures.

Historically, the outlook for patients with primary CNS lymphoma has not been as good as for many other lymphomas, but this is at least partly because people with CNS lymphoma tend to be older or have other serious health problems. However, the outlook for patients with primary CNS lymphoma has improved over the years mainly due to advances in treatment.

Primary intraocular lymphoma (lymphoma of the eye)

This is a rare type of lymphoma that starts in the eyeball and is often seen along with primary CNS lymphoma. It is the second most common cancer of the eye in adults, with ocular melanoma (eye melanoma) being the first. Most people with primary intraocular lymphoma are elderly or have immune system problems which may be due to AIDS or anti-rejection drugs after an organ or tissue transplant.

People may notice bulging of the eyeball without pain, vision loss, or a blurry vision. Many of the tests done to diagnose ocular melanoma are the same used to diagnose lymphoma of the eye.

The main treatment for lymphoma of the eye is external radiation therapy if the cancer is limited to the eye. Chemotherapy (chemo) or chemotherapy in combination with radiation may be used depending on the type of lymphoma and how far it has spread outside of the eye.

T-cell lymphomas

T-cell lymphomas make up less than 15% of non-Hodgkin lymphomas in the United States. These are types of lymphoma that affect T lymphocytes. There are many types of T-cell lymphoma, but they are all fairly rare.

T-lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia

T-lymphoblastic lymphoma accounts for about 1% of all lymphomas. It can be considered either a lymphoma or a type of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), depending on how much of the bone marrow is involved (leukemias have more bone marrow involvement). The cancer cells are very early forms of T cells.

T-lymphoblastic lymphoma often starts in the thymus (a small organ behind the breastbone and in front of the heart, which is where many T cells are made), and can grow into a large tumor in the mediastinum (the area between the lungs). This can cause trouble breathing and swelling in the arms and face.

T-lymphoblastic lymphoma is most common in teens or young adults, with males being affected more often than females.

T-lymphoblastic lymphoma is fast-growing, but if it hasn’t spread to the bone marrow when it is first diagnosed, the chance of cure with chemotherapy is quite good.

Often, the lymphoma form of this disease is treated in the same way as the leukemia form. For more information, see Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia.

Peripheral T-cell lymphomas

Peripheral T-cell lymphomas are uncommon types of lymphomas that develop from more mature forms of T cells.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (mycosis fungoides, Sezary syndrome, and others)

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas start in the skin. Skin lymphomas account for about 5% of all lymphomas.

- Mycosis fungoides (MF): Nearly half of all skin lymphomas are mycosis fungoides. Mycosis fungoides can occur in people of any age, but most who get it are in their 50s or 60s. Men are almost twice as likely as women to develop this lymphoma. The first sign of mycosis fungoides is one or more patchy, scaly, red lesions (abnormal areas) on the skin. Mycosis fungoides lesions can be very itchy. Often these lesions are the only symptom of mycosis fungoides. But in some people the disease can progress to more solid, raised tumors on the skin (called plaques). Because mycosis fungoides can be confused with other skin problems, it can be hard to diagnose at first. Several biopsies of the lesions might be needed before the diagnosis is confirmed. Over time, mycosis fungoides can spread across the skin or invade lymph nodes and organs like the liver. In many people this disease grows slowly, but it can sometimes grow more quickly, especially in older people. Some people with mycosis fungoides go on to develop Sezary syndrome. Rare variants of mycosis fungoides include folliculotropic mycosis fungoides, pagetoid reticulosis, and granulomatous slack skin.

- Sezary syndrome (SS): This is often thought of as an advanced form of mycosis fungoides, but these are actually different diseases. In Sezary syndrome, most or all of the skin is affected, instead of just patches of skin. People with Sezary syndrome typically have a very itchy, scaly red rash that can look like a severe sunburn. This is called generalized erythroderma. The skin is often thickened. Lymphoma cells, called Sezary cells, can be found in the blood (as well as in the lymph nodes). Whereas mycosis fungoides. is usually slow growing, Sezary syndrome tends to grow and spread faster, and is harder to treat. People with Sezary syndrome also often have further weakened immune systems, which increases their risk of serious infections.

- Adult T cell leukemia-lymphoma (ATLL): This rare type of T-cell lymphoma is more likely to start in other parts of the body, but it can sometimes be confined to the skin. It is linked to infection with the HTLV-1 virus (although most people infected with this virus do not get lymphoma). It is much more common in Japan and the Caribbean islands than other parts of the world. Adult T cell leukemia-lymphoma often grows quickly, but in some cases it advances slowly, or even shrinks on its own for a time.

- Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (C-ALCL): This lymphoma usually starts as one or a few tumors on the skin, which can vary in size. Some of these may break open (ulcerate). Most people with this disease are in their 50s or 60s, but it can also occur in children. It is found at least twice as often in men as in women. In most cases it does not spread beyond the skin, and the prognosis (outlook) is very good.

- Lymphomatoid papulosis: This is a benign, slow-growing disease that often comes and goes on its own, even without treatment. In fact, some doctors think of it not as a lymphoma, but rather as an inflammatory disease that might progress to a lymphoma. But under a microscope, it has features that look like primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (C-ALCL). Lymphomatoid papulosis often begins as several large pimple-like lesions that may break open in the middle. Lymphomatoid papulosis is seen in younger people more often than other T-cell skin lymphomas, with an average age of around 45. Men get this disease more often than women. Lymphomatoid papulosis often goes away without treatment, but it can take anywhere from a few months to many years to go away completely. Lymphomatoid papulosis doesn’t spread to internal organs and is not fatal. Rarely, some people with this skin disorder develop another, more serious type of lymphoma.

- Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma: Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma is a rare lymphoma that invades the deepest layers of the skin, where it causes nodules (lumps) to form. Most often these are on the legs, but they can occur anywhere on the body. Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma affects all ages and both sexes equally. It usually grows slowly and tends to have a good outlook.

- Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type: Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type is a rare type of lymphoma can start in T-cells or in other lymphocytes known as natural killer (NK) cells. It typically starts in the nose or sinuses, but sometimes it can start in the skin. Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type has been linked to infection with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and is more common in Asia and Central and South America. It tends to grow quickly.

- Primary cutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), rare subtypes: This is a group of rare skin lymphomas that don’t fit into any of the above categories. There are several types.

- Primary cutaneous gamma/delta T-cell lymphoma develops as thickened plaques (raised lesions) or actual tumors, mainly on skin of the arms and legs, but sometimes in the intestines or lining of the nose. This type of lymphoma tends to grow and spread quickly.

- Primary cutaneous CD8+ aggressive epidermotropic cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma develops as widespread patches, nodules and tumors that often break open in the middle. This type of lymphoma can sometimes look like mycosis fungoides, but a biopsy can tell them apart. This lymphoma tends to grow and spread quickly.

- Primary cutaneous acral CD8+ T-cell lymphoma is very rare, and typically starts as a nodule on the ear, although it can also start on other parts of the body, such as the nose, hand, or foot. It tends to grow slowly and can often be cured with treatment.

- Primary cutaneous CD4+ small/medium T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder often starts as a single area of thickening of the skin or a tumor on the head, neck, or upper body. This disease tends to grow slowly and can often be cured with treatment.

Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma

Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma is caused by infection with a virus called HTLV-1. It is rare in the United States, and much more common in Japan, the Caribbean, and parts of Africa – where infection with HTLV-1 is more common. It can affect the bone marrow (where new blood cells are made), lymph nodes, spleen, liver, skin, and other organs. There are 4 subtypes:

- The smoldering subtype tends to grow slowly and has a good prognosis.

- The chronic subtype also grows slowly and has a good prognosis.

- The acute subtype is the most common. It grows quickly like acute leukemia, so it needs to be treated right away.

- The lymphoma subtype grows more quickly than the chronic and smoldering types, but not as fast as the acute type.

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma accounts for about 4% of all lymphomas. It is more common in older adults. It tends to involve the lymph nodes as well as the spleen or liver, which can become enlarged. People with this lymphoma usually have fever, weight loss, and skin rashes and often develop infections. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma often progresses quickly. Treatment is often effective at first, but the lymphoma tends to come back (recur).

Extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type

Extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type is a rare type often involving the upper airway passages, such as the nose and upper throat, but it can also invade the skin, digestive tract, and other organs. Extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type is much more common in parts of Asia and South America. Cells of this lymphoma are similar in some ways to natural killer (NK) cells, another type of lymphocyte.

Enteropathy-associated intestinal T-cell lymphoma (EATL)

Enteropathy-associated intestinal T-cell lymphoma (EATL) is a lymphoma that occurs in the lining of the intestine. This lymphoma is most common in the small intestine, but can also occur in the colon. Symptoms can include severe abdominal (belly) pain, nausea, and vomiting. There are 2 subtypes of enteropathy-associated intestinal T-cell lymphoma (EATL):

- Type I enteropathy-associated intestinal T-cell lymphoma (EATL) occurs in some people with celiac disease also called gluten-sensitive enteropathy. Celiac disease is an autoimmune disease in which eating gluten, a protein found mainly in wheat and barley, causes the immune system to attack the lining of the intestine and other parts of the body. Type I EATL is rare among people who have had celiac disease since childhood, and is more common in people diagnosed as older adults. This lymphoma is more common in men than women.

- Type II enteropathy-associated intestinal T-cell lymphoma (EATL) is not linked to celiac disease and is less common than type I.

Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL)

About 2% of lymphomas are of anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL). It is more common in young people (including children), but it can also affect older adults. Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) tends to be fast-growing, but many people with this lymphoma can be cured.

There are different forms of anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL):

- Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) only affects the skin. This is discussed in more detail in Lymphoma of the Skin.

- Systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) can affect the lymph nodes and other organs, including the skin. Systemic ALCL is divided into 2 types based on whether the lymphoma cells have a change in the ALK gene. ALK-positive ALCL is more common in younger people and tends to have a better prognosis (outlook) than the ALK-negative type.

- Breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) is a rare type of ALCL that can develop in the breasts of women who have had implants. It seems to be more likely to occur if the implant surfaces are textured (as opposed to smooth).

Peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified (PTCL, NOS)

This name is given to T-cell lymphomas that don’t readily fit into any of the groups above. Most people diagnosed with these lymphomas are in their 60s. These lymphomas often involve the lymph nodes, but they can affect the skin, bone marrow, spleen, liver, and digestive tract, as well. As a group, these lymphomas tend to be widespread and grow quickly. Some patients respond well to chemotherapy, but over time these lymphomas tend to become harder to treat.

Non hodgkin’s lymphoma signs and symptoms

The most common symptom of non-Hodgkin lymphoma is a painless swelling in a lymph node (also known as lymphadenopathy), usually in the neck, armpit or groin.

Some people have no symptoms and the disease may only be discovered during a routine medical examination or while the patient is under care for an unrelated condition.

B Symptoms. Fever, drenching night sweats and loss of more than 10 percent of body weight over six months are sometimes termed “B symptoms” and are significant to the prognosis and staging of the disease. Other non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma symptoms, such as itching and fatigue, do not have the same prognostic importance as the symptoms designated as B symptoms. Furthermore, they are not considered to be B symptoms.

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma can cause many symptoms, such as:

- Painless swelling in one or more lymph node(s)

- Unexplained weight loss

- Fever

- Soaking night sweats

- Coughing, trouble breathing or chest pain

- Weakness and tiredness that don’t go away

- Loss of appetite

- Pain, swelling or a feeling of fullness in the abdomen (due to an enlarged spleen)

- Itchy skin

- Enlargement of the spleen or liver

- Rashes or skin lumps

The signs and symptoms of non-Hodgkin lymphoma are also associated with a number of other, less serious diseases.

A person who has signs or symptoms that suggest the possibility of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) is usually referred to a blood cancer specialist called a hematologist-oncologist. The doctor will order additional tests and a tissue biopsy to make a diagnosis.

A few people with lymphoma have abnormal cells in their bone marrow when they’re diagnosed.

This may lead to:

- persistent tiredness or fatigue

- an increased risk of infections

- excessive bleeding, such as nosebleeds, heavy periods and spots of blood under the skin.

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma complications

Life-threatening emergent complications of NHL should be considered during the initial workup and evaluation. Early recognition and prompt therapy are critical for these situations, which may interfere with and delay treatment of the underlying non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. These can include:

- Febrile neutropenia

- Hyperuricemia and tumor lysis syndrome – Presents with fatigue, nausea, vomiting, decreased urination, numbness, and tingling of legs and joint pain. Laboratory findings include an increase in uric acid, potassium, creatinine, phosphate, and a decrease in calcium level. This can be prevented with vigorous hydration and allopurinol.

- Spinal cord or brain compression

- Focal compression depending on the location and type of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma – airway obstruction (mediastinal lymphoma), intestinal obstruction and intussusception, ureteral obstruction

- Superior or inferior vena cava obstruction

- Hyperleukocytosis

- Adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma can cause hypercalcemia.

- Pericardial tamponade

- Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma with Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia can cause hyperviscosity syndrome.

- Hepatic dysfunction 6

- Venous thromboembolic disease 7

- Autoimmune hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia – can be observed with small lymphocytic lymphoma

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma causes

The exact cause of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma is not known but there are risk factors that may increase a person’s likelihood of developing the disease. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma is caused by a change (mutation) in the DNA of a type of white blood cell called lymphocytes, although the exact reason why this happens isn’t known. Non-Hodgkin lymphomas may be associated with various factors, including infections, environmental factors, immunodeficiency states, and chronic inflammation 8.

Various viruses have been attributed to different types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma 8:

- Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), a DNA virus, is associated with the causation of certain types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, including an endemic variant of Burkitt lymphoma.

- Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) causes adult T-cell lymphoma. It induces chronic antigenic stimulation and cytokine dysregulation, resulting in uncontrolled B- or T-cell stimulation and proliferation.

- Hepatitis C virus (HCV) results in clonal B-cell expansions. Splenic marginal zone lymphoma and diffuse large B cell lymphoma are some subtypes of NHL due to the Hepatitis C virus.

- Helicobacter pylori infection is associated with an increased risk of gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas, a primary gastrointestinal lymphoma.

Drugs like phenytoin, digoxin, TNF antagonist are also associated with non-Hodgkin lymphoma 8. Moreover, organic chemicals, pesticides, phenoxy-herbicides, wood preservatives, dust, hair dye, solvents, chemotherapy, and radiation exposure are also associated with the development of non-Hodgkin lymphoma 9, 10.

Congenital immunodeficiency states associated with increased risk of NHL are Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, severe combined immunodeficiency disease (SCID), and induced immunodeficiency states like immunosuppressant medications. Patients with AIDS (Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome) can have primary central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) lymphoma.

The autoimmune disorders like Sjögren syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and Hashimoto thyroiditis are associated with an increased risk of NHL. Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is associate with primary thyroid lymphomas 11. Celiac disease is also associated with an increased risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma can occur at any age, but a third cases are diagnosed in people 60 or over. Overall, non-Hodgkin lymphoma is common in age 65 to 74, the median age being 67 years. And the condition is slightly more common in men than women.

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma usually starts with an abnormal change in a white cell in a lymph node or lymphoid tissue called a lymphocyte. It can start in one of three major types of lymphocytes:

- B lymphocytes (B cells): B cells normally help protect the body against germs (bacteria or viruses) by making proteins called antibodies. The antibodies attach to the germs, marking them for destruction by other parts of the immune system.

- T lymphocytes (T cells): There are several types of T cells. Some T cells destroy germs or abnormal cells in the body. Other T cells help boost or slow the activity of other immune system cells.

- Natural killer (NK) cells, which attack virus-infected cells or tumor cells

About 85 percent of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma cases start in the B cells. Your doctor plans your treatment according to the type of cell your non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma developed in.

The abnormal lymphocyte grows out of control and produces more abnormal cells like it.

- These abnormal lymphocytes (lymphoma cells) accumulate and form masses (tumors). If non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma isn’t treated, the cancerous cells crowd out normal white cells, and the immune system can’t guard against infection effectively.

- Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma that develops in or spreads to other areas of the body where lymphoid tissue is found, such as the spleen, digestive tract and bone marrow, is called primary extranodal lymphoma.

- Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma is classified into more than 60 different subtypes. Doctors classify the non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma subtypes into categories that describe how rapidly or slowly the disease is progressing:

- Aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

- Indolent (slow-growing) non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

Risk Factors non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

A risk factor is anything that increases your chance of getting a disease like cancer. However, most people diagnosed with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma don’t have any obvious risk factors. And many people who have risk factors for the disease never develop it.

Researchers have found several factors that can affect a person’s chance of getting non-Hodgkin lymphoma. There are many types of lymphoma, and some of these factors have been linked only to certain types.

Immune suppression or having a weakened immune system is one of the most clearly established risk factors for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. People with autoimmune disease, acquired immunodeficiencies including human immunodeficiency virus infection (HIV) and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), and organ transplant recipients have an elevated risk for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. In some genetic (inherited) syndromes, such as ataxia-telangiectasia and Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, children are born with a deficient immune system. Along with an increased risk of serious infections, these children also have a higher risk of developing non-Hodgkin lymphoma. In addition, factors that suppress the immune system, such as chemical exposures or treatments for autoimmune diseases, may contribute to the development of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Autoimmune diseases. Some autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE or lupus), Sjogren (Sjögren) disease, celiac disease (gluten-sensitive enteropathy), and others have been linked with an increased risk of NHL. In autoimmune diseases, the immune system mistakenly sees the body’s own tissues as foreign and attacks them, as it would a germ. Lymphocytes (the cells from which lymphomas start) are part of the body’s immune system. The overactive immune system in autoimmune diseases may make lymphocytes grow and divide more often than normal. This might increase the risk of them developing into lymphoma cells.

Exposure to certain chemicals and drugs. Some studies have suggested that chemicals such as benzene and certain herbicides and insecticides (weed- and insect-killing substances) may be linked to an increased risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Research to clarify these possible links is still in progress.

Farming communities have a higher incidence of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Some studies suggest that specific ingredients in herbicides and pesticides such as organochlorine, organophosphate and phenoxy acid compounds, are linked to lymphoma. The number of lymphoma cases caused by such exposures has not been determined. More studies are needed to understand these associations.

Some chemotherapy drugs used to treat other cancers may increase the risk of developing non-Hodgkin lymphoma many years later. For example, patients who have been treated for Hodgkin lymphoma have an increased risk of later developing NHL. But it’s not totally clear if this is related to the disease itself or if it is an effect of the treatment.

Some studies have suggested that certain drugs used to treat rheumatoid arthritis, such as methotrexate and the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, might increase the risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. But other studies have not found an increased risk. Determining if these drugs increase risk is complicated by the fact that people with rheumatoid arthritis, which is an autoimmune disease, already have a higher risk of NHL.

Exposure to certain viruses and bacteria is associated with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. It is thought that infection with either a virus or a bacterium can lead to intense lymphoid cell proliferation, increasing the probability of a cancer-causing event in a cell. Here are some examples:

- Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection. Infection with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is an important risk factor for Burkitt lymphoma in some parts of Africa. In developed countries such as the United States, EBV is more often linked with lymphomas in people also infected with HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. EBV has also been linked with some less common types of lymphoma.

- Human T-cell lymphotropic virus-1 (HTLV-1). Human T-cell lymphotropic virus (HTLV-1) is most common in some parts of Japan and in the Caribbean region, but it’s found throughout the world. In the United States, it causes less than 1% of lymphomas. HTLV-1 spreads through sex and contaminated blood and can be passed to children through breast milk from an infected mother.

- Human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS). Infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), also known as the AIDS virus, can weaken the immune system. HIV infection is a risk factor for developing certain types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, such as primary central nervous system lymphoma, Burkitt lymphoma, and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

- Human herpes virus 8 (HHV-8) can also infect lymphocytes, leading to a rare type of lymphoma called primary effusion lymphoma. This lymphoma is most often seen in patients who are infected with HIV. HHV-8 infection is also linked to another cancer, Kaposi sarcoma. For this reason, another name for this virus is Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpes virus (KSHV).

- The bacterium Helicobacter Pylori (H Pylori). Helicobacter pylori, a type of bacteria known to cause stomach ulcers, has also been linked to mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma of the stomach.

- Hepatitis C. Long-term infection with the hepatitis C virus (HCV) seems to be a risk factor for certain types of lymphoma, such as splenic marginal zone lymphoma.

- Chlamydophila psittaci (formerly known as Chlamydia psittaci) is a type of bacteria that can cause a lung infection called psittacosis. It has been linked to MALT lymphoma in the tissues around the eye (called ocular adnexal marginal zone lymphoma).

- Infection with the bacterium Campylobacter jejuni has been linked to a type of MALT lymphoma called immunoproliferative small intestinal disease. This type of lymphoma, which is also sometimes called Mediterranean abdominal lymphoma, typically occurs in young adults in eastern Mediterranean countries.

Other conditions, such as Sjögren syndrome, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome and Klinefelter syndrome can predispose individuals to later development of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Age. Getting older is a strong risk factor for lymphoma overall, with most cases occurring in people in their 60s or older. But some types of lymphoma are more common in younger people.

Gender. Overall, the risk of NHL is higher in men than in women, but there are certain types of NHL that are more common in women. The reasons for this are not known.

Race, ethnicity, and geography. In the United States, whites are more likely than African Americans and Asian Americans to develop non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Worldwide, non-Hodgkin lymphoma is more common in developed countries, with the United States and Europe having some of the highest rates. Some types of lymphoma are linked to certain infections that are more common in some parts of the world.

Radiation exposure. Studies of survivors of atomic bombs and nuclear reactor accidents have shown they have an increased risk of developing several types of cancer, including NHL, leukemia,and thyroid cancer. Patients treated with radiation therapy for some other cancers, such as Hodgkin lymphoma, have a slightly increased risk of developing non-Hodgkin lymphoma later in life. This risk is greater for patients treated with both radiation therapy and chemotherapy.

Being overweight or obese. Some studies have suggested that being overweight or obese might increase your risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. More research is needed to confirm these findings. In any event, staying at a healthy weight, keeping physically active, and following a healthy eating pattern that includes plenty of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, and that limits or avoids red and processed meats, sugary drinks, and highly processed foods has many known health benefits outside of the possible effect on lymphoma risk.

Breast implants. Although it is rare, some women with breast implants develop a type of anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) in their breast. This seems to be more likely with implants that have textured (rough) surfaces (as opposed to smooth surfaces).

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma isn’t infectious and isn’t thought to run in families, although your risk may be slightly increased if a first-degree relative (such as a parent or sibling) has had lymphoma.

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma prevention

There is no sure way to prevent non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Most people with NHL have no risk factors that can be changed, so there is no way to protect against these lymphomas. But there are some things you can do that might lower your risk for non-Hodgkin lymphoma, such as limiting your risk of certain infections and doing what you can to maintain a healthy immune system.

Infection with HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, is known to increase the risk non-Hodgkin lymphoma, so one way to limit your risk is to avoid known risk factors for HIV, such as intravenous drug use or unprotected sex with many partners.

Preventing the spread of the human T-cell lymphotropic virus (HTLV-1) could have a great impact on non-Hodgkin lymphoma in areas of the world where this virus is common, such as Japan and the Caribbean region. The virus is rare in the United States but seems to be increasing in some areas. The same strategies used to prevent HIV spread could also help control HTLV-1.

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection has been linked to some lymphomas of the stomach. Treating H. pylori infections with antibiotics and antacids may lower this risk, but the benefit of this strategy has not been proven yet. Most people with H. pylori infection have no symptoms, and some have only mild heartburn. More research is needed to find the best way to detect and treat this infection in people without symptoms.

Some lymphomas are caused by treatment of other cancers with radiation and chemotherapy or by the use of immune-suppressing drugs to avoid rejection of transplanted organs. Doctors are trying to find better ways to treat cancer and organ transplant patients without increasing the risk of lymphoma as much. But for now, the benefits of these treatments still usually outweigh the small risk of developing lymphoma many years later.

Some studies have suggested that being overweight or obese may increase your risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Staying at a healthy weight, keeping physically active, and following a healthy eating pattern that includes plenty of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, and that limits or avoids red and processed meats, sugary drinks, and highly processed foods may help protect against lymphoma, but more research is needed to confirm this.

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma diagnosis

Most people with non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) see their doctor because they have felt a lump that hasn’t gone away, they develop some of the other symptoms of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, or they just don’t feel well and go in for a check-up.

Your doctor will likely ask you about your personal and family medical history. He or she may then have you undergo tests and procedures used to diagnose non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, including:

- Physical exam. Your doctor checks for swollen lymph nodes, including in your neck, underarm and groin, as well as for a swollen spleen or liver.

- Blood and urine tests. Blood and urine tests may help rule out an infection or other disease.

- Imaging tests. Your doctor may recommend imaging tests to look for signs of lymphoma cells elsewhere in your body. Tests may include CT, MRI and positron emission tomography (PET).

- Lymph node test. Your doctor may recommend a lymph node biopsy procedure to remove all or part of a lymph node for laboratory testing. Analyzing lymph node tissue in a lab may reveal whether you have non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and, if so, which type.

- Bone marrow test. A bone marrow biopsy and aspiration procedure involves inserting a needle into your hipbone to remove a sample of bone marrow. The sample is analyzed to look for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma cells.

- Lumbar puncture (spinal tap). If there’s a concern that the lymphoma may affect the fluid around your spinal cord, your doctor might recommend a procedure to remove some of the fluid for testing. During a spinal tap, the doctor inserts a small needle into the spinal canal in your lower back.

Other tests and procedures may be used depending on your situation.

The only way to confirm a diagnosis of non-Hodgkin lymphoma is by carrying out a lymph node biopsy. This is a minor surgical procedure where a sample of affected lymph node tissue is removed and studied in a laboratory. But a lymph node biopsy is not always done right away because many symptoms of non-Hodgkin lymphoma can also be caused by other problems, like an infection, or by other kinds of cancer. For example, enlarged lymph nodes are more often caused by infections than by lymphoma. Because of this, doctors often prescribe antibiotics and wait a few weeks to see if the lymph nodes shrink. If the nodes stay the same or continue to grow, the doctor might order a biopsy.

A lymph node biopsy might be needed right away if the size, texture, or location of a lymph node or the presence of other symptoms strongly suggests lymphoma.

Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma can develop in parts of the body that do not involve lymph nodes, such as the lung or bone. When lymphoma is detected exclusively outside of the lymph nodes, it is called “primary extranodal lymphoma,” and the biopsy specimen is taken from that involved tissue.

Lymph Node Biopsy

Diagnosing non-Hodgkin lymphoma usually involves performing a lymph node biopsy. If the biopsy confirms that you have non-Hodgkin lymphoma, your doctor performs additional tests to stage the lymphoma.

The purpose of a lymph node biopsy is to:

- Confirm a diagnosis

- Identify your non-Hodgkin lymphoma subtype

- Develop a treatment plan.

There are several types of biopsies. Doctors choose which one to use based on each person’s situation.

Excisional or incisional lymph node biopsy

This is the preferred and most common type of lymph node biopsy if lymphoma is suspected, because it almost always provides enough of a sample to diagnose the exact type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

In this procedure, a surgeon cuts through the skin to remove the lymph node.

- If the doctor removes the entire lymph node, it is called an excisional biopsy.

- If a small part of a larger tumor or node is removed, it is called an incisional biopsy.

If the enlarged node is just under the skin, this is a fairly simple operation that can often be done with local anesthesia (numbing medicine). But if the node is inside the chest or abdomen, you will be sedated (given drugs to make you drowsy and relaxed) or given general anesthesia (drugs to put you into a deep sleep).

Needle lymph node biopsy

Needle biopsies are less invasive than excisional or incisional biopsies, but the drawback is that they might not remove enough of a sample to diagnose lymphoma (or to determine which type it is). Most doctors do not use needle biopsies to diagnose lymphoma. But if the doctor suspects that your lymph node is enlarged because of an infection or by the spread of cancer from another organ (such as the breast, lungs, or thyroid), a needle biopsy may be the first type of biopsy done. An excisional biopsy might still be needed even after a needle biopsy has been done, to diagnose and classify lymphoma.

There are 2 main types of needle biopsies:

- In a fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy, the doctor uses a very thin, hollow needle attached to a syringe to withdraw (aspirate) a small amount of tissue from an enlarged lymph node or a tumor mass.

- For a core needle biopsy, the doctor uses a larger needle to remove a slightly larger piece of tissue.

To biopsy an enlarged node just under the skin, the doctor can aim the needle while feeling the node. If the node or tumor is deep inside the body, the doctor can guide the needle using a computed tomography (CT) scan or ultrasound (see descriptions of imaging tests later in this section).

If lymphoma has already been diagnosed, needle biopsies are sometimes used to check abnormal areas in other parts of the body that might be from the lymphoma spreading or coming back after treatment.

Lab Tests to Confirm a Diagnosis

After your doctor takes samples of your lymph node and tissues, a hematopathologist examines them under a microscope to look for identifying characteristics of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. He or she confirms a diagnosis and identifies the NHL subtype. A hematopathologist is a specialist who studies blood cell diseases by looking at samples of blood and bone marrow cells and other tissues.

The hematopathologist uses one or more lab tests such as those below to examine your cells:

- Immunophenotyping and flow cytometry: For both flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry, the biopsy samples are treated with antibodies that stick to certain proteins on cells. The cells are then looked at in the lab (immunohistochemistry) or with a special machine (for flow cytometry), to see if the antibodies attached to them. These tests can help determine whether a lymph node is swollen because of lymphoma, some other cancer, or a non-cancerous disease. The tests can also be used for immunophenotyping – determining which type of lymphoma a person has, based on certain proteins in or on the cells. Different types of lymphocytes have different proteins on their surface, which correspond to the type of lymphocyte and how mature it is.

- Chromosome tests: Normal human cells have 23 pairs of chromosomes (strands of DNA), each of which is a certain size and looks a certain way in the lab. But in some types of lymphoma, the cells have changes in their chromosomes, such as having too many, too few, or abnormal chromosomes. These changes can often help identify the type of lymphoma.

- Cytogenetic analysis: In this lab test, the cells are checked for any abnormalities in the chromosomes.

- Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH): This test looks more closely at lymphoma cell DNA using special fluorescent dyes that only attach to specific genes or parts of chromosomes. FISH can find most chromosome changes that can be seen in standard cytogenetic tests, as well as some gene changes too small to be seen with cytogenetic testing. FISH is very accurate and can usually provide results within a couple of days.

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR): PCR is a very sensitive DNA test that can find gene changes and certain chromosome changes too small to be seen with a microscope, even if very few lymphoma cells are present in a sample.

Since non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma is a difficult disease to diagnose, you may want to get a second medical opinion by an experienced hematopathologist before you begin treatment. Some types of NHL can be confused with each other. The appropriate treatment depends on having the correct diagnosis.

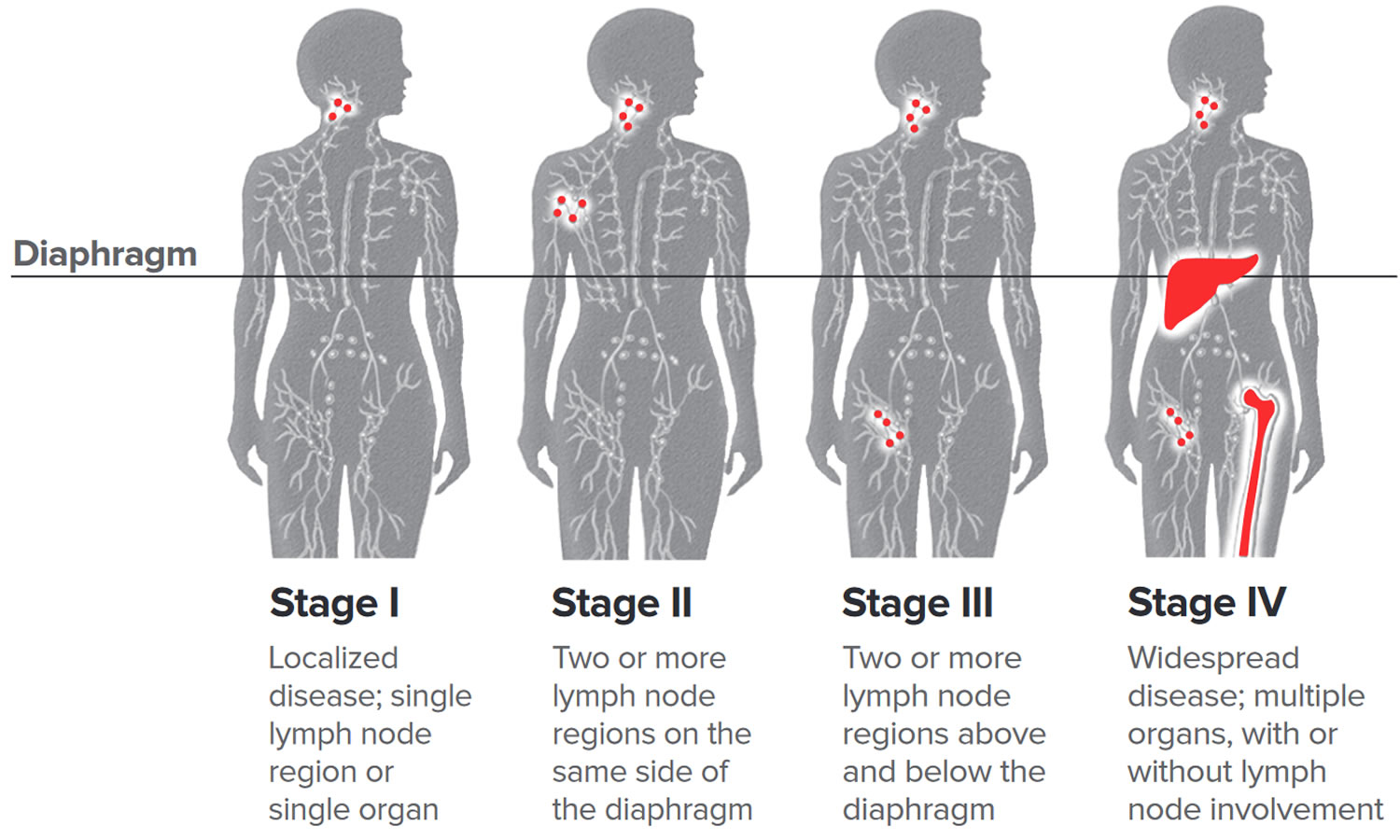

Staging Tests

Once your doctor confirms an non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma diagnosis, he or she runs more tests to stage your disease. Staging identifies the extent of your disease and where it’s located in your body.

Staging tests include:

- Physical exam

- Biopsies of enlarged lymph nodes or other abnormal areas

- Blood tests

- Imaging tests, such as PET and CT scans

- Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy (often but not always done)

- Lumbar puncture (spinal tap – this may not need to be done)

Imaging Tests

Your doctor conducts one or more imaging tests (also called diagnostic radiology), along with a physical exam, to look for:

- The location and distribution of lymph node enlargement

- Whether organs other than the lymph nodes are involved

- If there are very large masses of tumors in one site or another.

Imaging tests may include:

- Chest x-rays. The chest might be x-rayed to look for enlarged lymph nodes in this area.

- CT (computed tomography) scan. A CT scan combines many x-rays to make detailed, cross-sectional images of your body. This scan can help tell if any lymph nodes or organs in your body are enlarged. CT scans are useful for looking for lymphoma in the abdomen, pelvis, chest, head, and neck.

- CT-guided needle biopsy: A CT can also be used to guide a biopsy needle into a suspicious area. For this procedure, you lie on the CT scanning table while the doctor moves a biopsy needle through the skin and toward the area. CT scans are repeated until the needle is in the right place. A biopsy sample is then removed to be looked at in the lab.

- FDG-PET (fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography) scan. For a PET scan, you are injected with a slightly radioactive form of sugar (fluorodeoxyglucose [FDG]), which collects mainly in cancer cells. A special camera is then used to create a picture of areas of radioactivity in the body. The picture is not detailed like a CT or MRI scan, but it can provide helpful information about your whole body. If you have lymphoma, a PET scan might be done to:

- See if an enlarged lymph node contains lymphoma.

- Find small areas that might be lymphoma, even if the area looks normal on a CT scan.

- Check if a lymphoma is responding to treatment. Some doctors will repeat the PET scan after 1 or 2 courses of chemotherapy. If the chemotherapy is working, the lymph nodes will no longer absorb the radioactive sugar.

- Help decide whether an enlarged lymph node still contains lymphoma or is just scar tissue after treatment.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Like CT scans, MRI scans show detailed images of soft tissues in the body. But MRI scans use radio waves and strong magnets instead of x-rays. This test is not used as often as CT scans for lymphoma, but if your doctor is concerned about spread to the spinal cord or brain, MRI is very useful for looking at these areas.

- PET-CT scan. Some machines can do both a PET scan and a CT scan at the same time. This lets the doctor compare areas of higher radioactivity on the PET scan with the more detailed appearance of that area on the CT scan. PET/CT scans can often help pinpoint the areas of lymphoma better than a CT scan alone.

- Bone scan. Bone scan is usually done if a person is having bone pain or has lab results that suggest the lymphoma may have reached the bones. For bone scans, a radioactive substance called technetium is injected into a vein. It travels to damaged areas of bone, and a special camera can then detect the radioactivity. Lymphoma often causes bone damage, which may be seen on a bone scan. But bone scans can’t show the difference between cancers and non-cancerous problems, such as arthritis and fractures, so further tests might be needed.

Blood Tests

After your blood is taken, it’s sent to a lab for a complete blood count (CBC) and more blood work. Blood tests are used to:

- Determine whether lymphoma cells are present in the blood and if the special proteins (called “immunoglobulins”) made by lymphocytes are either deficient or abnormal

- Check indicators of disease severity by examining blood protein levels, uric acid levels and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)

- Assess kidney and liver functions

- Measure two important biological markers, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and beta2-microglobulin which are helpful prognostic indicators for several non-Hodgkin lymphoma subtypes

- For some types of lymphoma or if certain treatments might be used, your doctor may also advise you to have tests to see if you’ve been infected with certain viruses, such as hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Infections with these viruses may affect your treatment.

A complete blood count (CBC) may show:

- Anemia (low red blood cell counts)

- Neutropenia (low levels of neutrophils, a type of white blood cells)

- Thrombocytopenia (low platelet levels)

Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy

Most patients diagnosed with NHL undergo a bone marrow biopsy to make sure there is no spread of the disease to the bone marrow and to evaluate the use of specific therapies including radioimmunotherapy (a combination of radiation therapy and immunotherapy). A bone marrow biopsy may not always be required for patients with early-stage disease who also have low-risk features, for example, NHL with no B symptoms and no large masses.

For a bone marrow aspiration, you lie on a table (either on your side or on your belly). After cleaning the skin over the hip, the doctor numbs the area and the surface of the bone with local anesthetic, which can cause a brief stinging or burning sensation. A thin, hollow needle is then inserted into the bone and a syringe is used to suck out a small amount of liquid bone marrow. Even with the anesthetic, most people still have some brief pain when the marrow is removed.

A bone marrow biopsy is usually done just after the aspiration. A small piece of bone and marrow is removed with a slightly larger needle that is pushed into the bone. The biopsy can also cause some brief pain.

Lumbar puncture (spinal tap)

Lumbar puncture (spinal tap) test looks for lymphoma cells in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which is the liquid that bathes the brain and spinal cord. Most people with lymphoma will not need this test. But doctors may order it for certain types of lymphoma or if a person has symptoms that suggest the lymphoma may have reached the brain.

For this test, you may lie on your side or sit up. The doctor first numbs an area in the lower part of your back over the spine. A small, hollow needle is then placed between the bones of the spine to withdraw some of the fluid.

Pleural or peritoneal fluid sampling

Lymphoma that has spread to the chest or abdomen can cause fluid to build up. Pleural fluid (inside the chest) or peritoneal fluid (inside the abdomen) can be removed by placing a hollow needle through the skin into the chest or abdomen.

- When this procedure is used to remove fluid from the area around the lung, it’s called a thoracentesis.

- When it is used to collect fluid from inside the abdomen, it’s known as a paracentesis.

The doctor uses a local anesthetic to numb the skin before inserting the needle. The fluid is then taken out and checked in the lab for lymphoma cells.

Other Tests for Specific Subtypes

Certain tests are performed for specific subtypes only and not necessary for all patients with NHL. They include:

- Full evaluation of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, including upper and lower endoscopies for patients who have disease involving the gastrointestinal tract, such as mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma

- Colonoscopy for patients with mantle cell lymphoma (routine colonoscopy is important for all persons beginning at age 50, or earlier if there is a family history of colon cancer)

- Testicular ultrasound for patients who have a testicular mass

- Spinal tap (lumbar puncture) and/or MRI of the brain or spinal column may be required for patients with certain subtypes or symptoms that suggest central nervous system involvement.

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma Subtypes

More than 60 specific Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma subtypes have been identified and assigned names by the World Health Organization (WHO). NHL subtypes are categorized by the characteristics of the lymphoma cells, including their appearance, the presence of proteins on the surface of the cells and their genetic features. It’s important to know your subtype since it plays a large part in determining the type of treatment you’ll receive. A hematopathologist, a doctor who specializes in the diagnosis of blood disorders and blood cancers, should review your biopsy specimens.

Specialists further characterize the Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma subtypes according to how the disease progresses:

- Aggressive lymphomas also known as high grade lymphomas are fast-moving and account for about 60 percent of all NHL cases. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common aggressive NHL subtype.

- Indolent lymphomas also known as low grade lymphomas are slow-moving and tend to grow more slowly and have fewer signs and symptoms when first diagnosed. Slow-growing or indolent subtypes represent about 40 percent of all NHL cases. Follicular lymphoma (FL) is the most common subtype of indolent Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

The treatments for aggressive and indolent lymphomas are different. When a patient’s rate of disease progression is between indolent and aggressive, he or she is considered to have “intermediate grade” disease. Some cases of indolent Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma can transform into aggressive Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Table 1. Most Common Subtypes of Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma

| Most Common Subtypes of Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma |

|---|

Aggressive

|

Indolent

|

Below are the Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma diagnostic designations of the subtypes for non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The descriptive part of the names (eg, follicular, mantle cell or marginal zone) in some disease subtypes refers to the specific areas of the lymph nodes (the follicle, mantle and marginal zones) where the lymphoma appears to have originated.

Table 2. Diagnostic Designations for Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Subtypes