Contents

Gleason Score

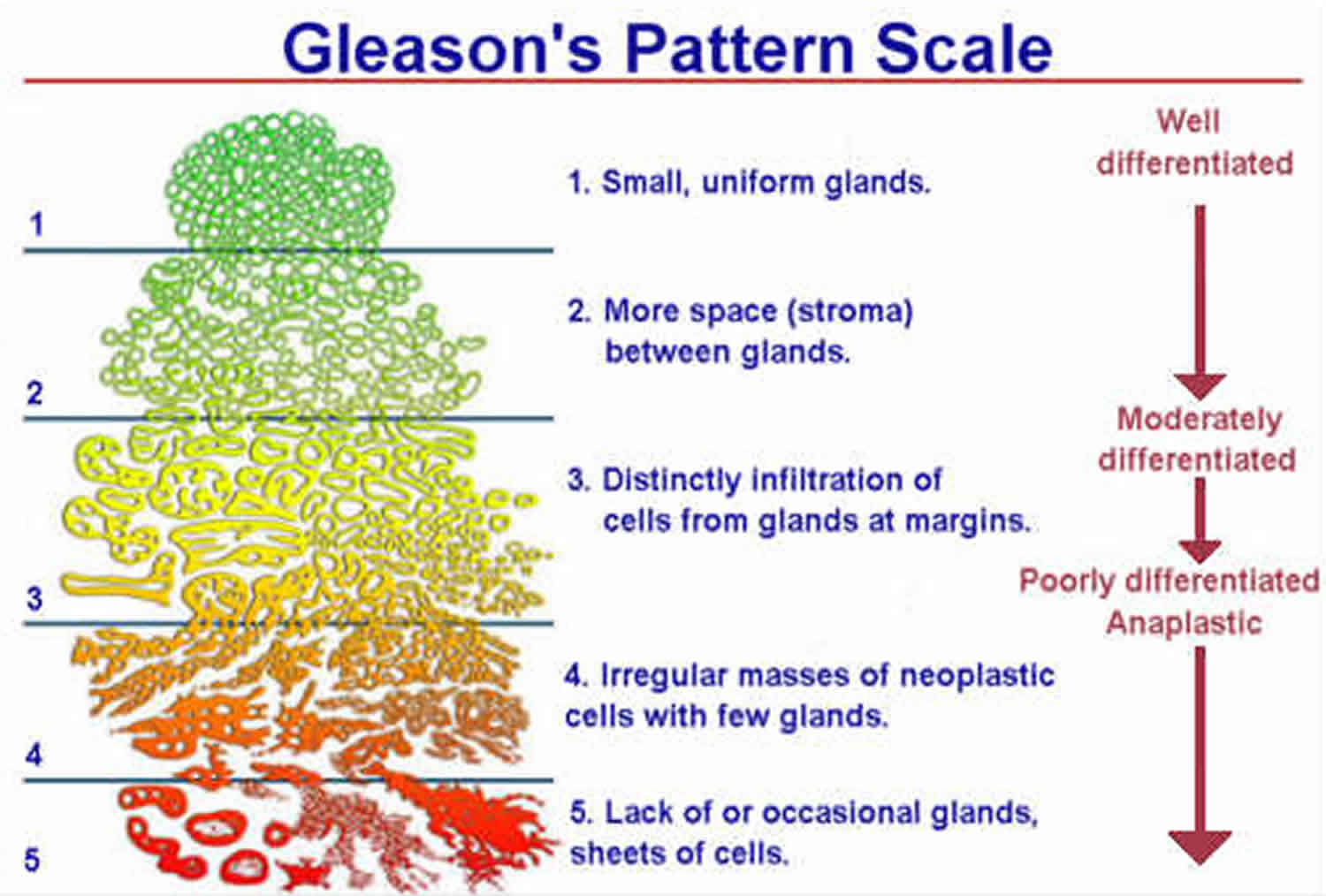

Gleason Score also called the Gleason Sum indicates the grade or “aggressiveness” of your prostate cancer (prostate adenocarcinoma) based on how abnormal the cancer cells in a biopsy sample look under a microscope and how quickly they are likely to grow and spread 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7. The pathologist grades each sample of prostate cancer cells from 3 to 5 based on how quickly they are likely to grow or how aggressive the cells look (grades 1 and 2 are not often used). You may hear this grade being called the Gleason Grade. Higher-grade cancers look more abnormal, and they’re more likely to grow and spread quickly. The Gleason scoring system is based on the microscopic arrangement, architecture or pattern of the glands in prostate cancer biopsy samples rather than on the individual cellular characteristics that define most other cancers. Gleason score is also the strongest clinical predictor of prostate cancer progression 8.

Gleason Grade

- Gleason grade 1 is assigned if the prostate cancer looks a lot like normal prostate tissue.

- Gleason grade 5 is assigned if the prostate cancer looks very abnormal.

- Gleason grades 2 through 4 have features in between these extremes.

Most prostate cancers contain cells that are different Gleason Grades. The Gleason Score is calculated by adding together the two grades of cancer cells that make up the largest areas of the biopsied tissue sample. Doctors derive your overall Gleason Score also called the Gleason Sum by adding together the 2 most common Gleason Grades yielding a score ranging from 2 to 10. So for example, if the most common Gleason Grade is 3, and the second most common is Gleason Grade is 4, then the overall Gleason Score (Gleason Sum) is 7. Or your pathologist might write the report with Gleason scores separately as 3 + 4 = 7. The higher the Gleason Score (Gleason Sum), the more aggressive your prostate cancer is likely to be and more difficult to cure 9. In theory, the Gleason score (Gleason sum) can be between 2 and 10, but scores below 6 are not often used. This combined Gleason score is also now called the Grade Group. The Grade Group has now replaced the Gleason grade as doctors think the Grade Group is a more accurate way to grade prostate cancer cells. There are 5 Grade Groups. Grade Group 1 is the least aggressive and Grade Group 5 is the most aggressive.

The Grade Groups are important factors that help your doctor recommend if you need treatment. Doctors also consider the following things:

- your PSA blood test level

- the TNM stage of your cancer. The TNM staging system is a widely used method for classifying the extent of cancer, especially solid tumors. The TNM staging system assesses the tumor (T), lymph nodes (N), and metastasis (M) to determine the stage of your cancer. The TNM staging system helps doctors understand the severity and spread of the cancer, which informs treatment decisions and prognosis.

To find out the Gleason Score (Gleason Sum) or Grade Group, a pathologist looks at several samples of cells (biopsies) from your prostate. The Gleason Score (Gleason Sum) is calculated based on the dominant histologic grades, from grade 1 (well differentiated, representing an almost normal microscopic glandular pattern and appearance) to grade 5 (very poorly differentiated where no glandular architecture remains, and there are only sheets of abnormal cancer cells) 8.

Because there is some evidence that the least-differentiated component of the prostate cancer biopsy specimen may provide independent prognostic information, the Gleason Score (Gleason Sum) is often provided by its separate components, for example Gleason score 3 + 4 = 7 versus 4 + 3 = 7 10. The Gleason prostate cancer score has been shown, over time, to be the most reliable and predictive histological grading system available 11. Originally developed by pathologist Dr. Donald Gleason in the 1960s, it has stood the test of time and has been universally adopted for all prostate cancer pathological descriptions 12.

For most kinds of cancer, tumor grade is determined by looking at individual cancer cells through a microscope using a high level of magnification to examine the details of those cells. Gleason Score (Gleason Sum) is different. With this method, a pathologist examines prostate tissue samples under a microscope using low magnification to observe the patterns of the cancer cells.

Each pattern is given a number, usually 3, 4, or 5. Because many prostate cancers contain more than one pattern, the two most common patterns are added together to make the Gleason Score (Gleason Sum). If the patterns are very similar or if only one pattern is found, then the cancer is given two of the same number.

A prostate cancer biopsy also differs from other forms of cancer in the number of samples a pathologist examines. Rather than just one or two tissue samples, 12 samples are usually taken for a prostate biopsy. Of those samples, some may have different Gleason scores. If that’s the case, the pathologist assigns the highest score observed.

It is worth noting, however, that if only one or two of the samples have a score of 8 and the others are lower, or if some do not show evidence of cancer at all, then the outlook is better than if nine or ten samples are at 8. Your doctor will take that into account when evaluating the outlook for your cancer.

Your pathologist also will review the amount or percentage of cancer found in each sample. If the percentage is low, the overall outlook is better than if the percentage of cancerous tissue is high in the samples.

The Gleason Score (Gleason Sum) always contains two grades in the form of numbers and then a total score:

- The predominant Gleason Grade pattern is always the first number, 1 to 5, and

- The second number would be any secondary or minor pattern, also graded 1 to 5.

So the absolute best and lowest risk Gleason Score (Gleason Sum) would be Gleason Grade 1 + 1 = 2, and the worst high-grade pathology would be Gleason Grade 5 + 5 = 10. In real life, these histological extremes are almost never seen 13.

If only one Gleason Grade or pattern is seen, then the Gleason Score (Gleason Sum) would consist of the same Gleason grade repeated and added together as in Gleason 3 + 3 = 6; which happens to be the most commonly found Gleason score 14.

Based on the Gleason Score, prostate cancers are often divided into 3 groups:

- Gleason score of 3 + 3 = 6 or less may be called Well-differentiated or Low-grade prostate cancer. These cancers tend to grow slowly and are unlikely to spread. In fact, some doctors have questioned whether these should even be called cancers 13.

- Gleason score of 3 + 4 = 7 may be called Moderately-differentiated or Intermediate-grade prostate cancer. This would mean that most of the tumor was Gleason grade 3, but there was a smaller portion that was the more aggressive Gleason grade 4 15.

- Gleason scores of 8 to 10 may be called Poorly-differentiated or High-grade prostate cancer 13.

Of the factors related to prostate cancer that doctors take into consideration when deciding on treatment, Gleason score is probably the most important one. The Gleason score will help your doctor understand if the cancer is as a low-, intermediate- or high-risk disease. Generally, Gleason scores of 6 are treated as low risk cancers. Gleason scores of around 7 are treated as intermediate/mid-level cancers. There are two types of these scores. A 4+3 tumor is more aggressive than a 3+4 tumor. That’s because more of the higher aggressive grade tumor was found. Gleason scores of 8 and above are treated as high-risk cancers. Gleason 8, 9 and 10 tumors are the most aggressive. Some of these high-risk tumors may have already spread by the time they are found. Talk to your health care provider about your Gleason score.

In most cases, treatment with radiation and hormonal therapy or with surgery is recommended based on a total Gleason score of 8. Gleason score of 8 likely came from two very similar patterns of 4 and 4. In some cases, a score of 8 may come from a pattern of 5 and 3 or 3 and 5, but those are not common. The first number identifies the primary pattern, or the one seen most predominately in the sample. The second number is the secondary pattern, or one that is visible but not as widespread as the primary pattern.

Generally, with a Gleason score of 8 or higher, treatment is recommended, as long as you do not have other medical problems that would make it hard for you to have radiation and hormonal therapy or surgery. Depending on age and the specific numbers that make up the Gleason score, men who have scores of 6 or 7 may not need immediate treatment. Instead, their doctors may suggest a program of active surveillance to monitor the cancer and to see if it progresses.

Before treatment begins in patients who have higher Gleason scores, most doctors suggest imaging exams such as bone and CT scans or MRI studies of the pelvis and abdomen. This allows your doctor to see if the cancer has spread beyond the prostate and will help your doctor recommend which treatment options are best for you.

Furthermore, there is evidence that, over time, pathologists have tended to award higher Gleason scores to the same histologic patterns, a phenomenon sometimes termed grade inflation 16. This phenomenon complicates comparisons of outcomes in current versus historical patient series. For example, prostate biopsies from a population-based cohort of 1,858 men diagnosed with prostate cancer from 1990 through 1992 were re-read in 2002 to 2004 17. The contemporary Gleason score readings were an average of 0.85 points higher (95% confidence interval, 0.79–0.91; P < .001) than the same slides read a decade earlier. As a result, Gleason-score standardized prostate cancer mortality rates for these men were artifactually improved from 2.08 to 1.50 deaths per 100-person years—a 28% decrease even though overall outcomes were unchanged 18.

While architecture or pattern, as described by the Gleason score, is certainly a major component of the histological diagnosis of prostate cancer, it is not the only criteria. For example, prostate specific membrane antigen is a transmembrane carboxypeptidase that exhibits folate hydrolase activity which is overexpressed in prostate cancer tissues. Its presence would suggest prostate cancer 19.

Other significant microscopic histological features and indicators of prostate cancer would include 20:

- Infiltrative glandular growth pattern

- Absence of a basal cell layer

- Atypically enlarged cell nuclei with large nucleoli

- Increased mitotic figures

- Intraluminal wispy blue mucin

- Pink amorphous secretions

- Intraluminal crystalloids

- Adjacent High-Grade Prostatic Intraepithelial Neoplasia (High-Grade PIN)

- Amphophilic cytoplasm

The number of positive biopsies also has prognostic value. In a study of 960 intermediate grade (Gleason 3 + 4 = 7) prostate cancers followed for at least four years, 86% of patients with less than 34% positive biopsies demonstrated a stable PSA compared with only 11% of patients who had more than 50% positive biopsies.

Cancer volume is another important prognostic parameter, but it is difficult to measure accurately with available technology. Prostatic MRI is currently our best instrumentation for estimating tumor volume 21.

Perineural invasion is somewhat helpful in predicting extracapsular tumor extension and may be associated with slightly higher tumor aggressiveness, but studies are conflicting on its clinical usefulness 22.

Figure 1. Gleason score

New Gleason Scoring System

In recent years, doctors have come to realize that the Gleason score might not always be the best way to describe the grade of the prostate cancer, for a couple of reasons:

- Prostate cancer outcomes can be divided into more than just the 3 groups mentioned above. For example, men with a Gleason score (Gleason sum) 3+4=7 cancer tend to do better than those with a 4+3=7 cancer. And men with a Gleason score (Gleason sum) 8 cancer tend to do better than those with a Gleason score of 9 or 10.

- The scale of the Gleason score can be misleading for patients. For example, a man with a Gleason score 6 cancer might assume that his cancer is in the middle of the range of grades (which in theory go from 2 to 10), even though grade 6 cancers are actually the lowest grade seen in practice. This assumption might lead a man to think his cancer is more likely to grow and spread quickly than it really is, which might affect his decisions about treatment.

Because of this, doctors have developed 5 Grade Groups, ranging from 1 (most likely to grow and spread slowly [least aggressive]) to 5 (most likely to grow and spread quickly [most aggressive]). The Grade Groups will likely replace the Gleason score over time, but currently you might see either one (or both) on a biopsy pathology report.

Along with Gleason Grade of the prostate cancer (if it is present), the pathology report often contains other information about the cancer, such as:

- The number of biopsy core samples that contain cancer (for example, “7 out of 12”)

- The percentage of cancer in each of the cores

- Whether the cancer is on one side (left or right) of the prostate or on both sides (bilateral)

In 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) proposed a new classification system based on clinical experience with the old Gleason scoring system that suggested very little difference in clinical outcomes in lower Gleason score patients, but somewhat different ones in the higher grades. The following is a summary of the “New” Gleason system or Grade Groups 23:

- Grade group 1 (Gleason score less than or equal to 6): Only individual discrete well-formed glands

- Grade group 2 (Gleason score 3 + 4 = 7): Predominantly well-formed glands with a lesser component of poorly-formed, fused or cribriform glands

- Grade group 3 (Gleason score 4 + 3 = 7): Predominantly poorly-formed, fused, or cribriform glands with a lesser component of well-formed glands

- Grade group 4 (Gleason score 8): Only poorly-formed/fused/cribriform glands; or predominantly well-formed glands with a lesser component lacking glands; or predominantly lacking glands with a lesser component of well-formed glands

- Grade group 5 (Gleason scores 9 or 10): Lacks gland formation (or with necrosis) with or without poorly-formed, fused or cribriform glands

In clinical practice, group 1 is considered “low grade,” Group 2 is “intermediate grade,” and group 3 or higher is “high grade” disease 11.

Table 1. Gleason Score and Grade Groups

| Gleason score | Grade Group | What it means |

|---|---|---|

| Gleason score 6 (or 3 + 3 = 6) | Grade Group 1 | The cells look similar to normal prostate cells. The cancer is likely to grow very slowly, if at all |

| Gleason score 7 (or 3 + 4 = 7) | Grade Group 2 | Most cells still look similar to normal prostate cells. The cancer is likely to grow slowly |

| Gleason score 7 (or 4 + 3 = 7) | Grade Group 3 | The cells look less like normal prostate cells. The cancer is likely to grow at a moderate rate |

| Gleason score 8 (or 4 + 4 = 8) | Grade Group 4 | Some cells look abnormal. The cancer might grow quickly or at a moderate rate |

| Gleason score 9 or 10 (or 4 + 5 = 9, 5 + 4 = 9 or 5 + 5 = 10) | Grade Group 5 | The cells look very abnormal. The cancer is likely to grow quickly |

Suspicious results

Sometimes when the prostate cells are seen, they don’t look like cancer, but they’re not quite normal, either. These results are often reported as suspicious.

Prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN): In prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia, there are changes in how the prostate cells look, but the abnormal cells don’t look like they’ve grown into other parts of the prostate (like cancer cells would). PIN is often divided into 2 groups:

- Low-grade PIN: the patterns of prostate cells appear almost normal

- High-grade PIN: the patterns of cells look more abnormal

Many men begin to develop low-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia at an early age but don’t necessarily develop prostate cancer. The importance of low-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia in relation to prostate cancer is still unclear. If low-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia is reported on a prostate biopsy, the follow-up for patients is usually the same as if nothing abnormal was seen.

If high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia is found on a biopsy, there is about a 20% chance that cancer may already be present somewhere else in the prostate gland. This is why doctors often watch men with high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia carefully and may advise a repeat prostate biopsy, especially if the original biopsy did not take samples from all parts of the prostate.

Atypical small acinar proliferation: This is sometimes just called atypia. In atypical small acinar proliferation, the cells look like they might be cancerous when viewed under the microscope, but there are too few of them to be sure. If atypical small acinar proliferation is found, there’s a high chance that cancer is also present in the prostate, which is why many doctors recommend getting a repeat biopsy within a few months.

Proliferative inflammatory atrophy: In proliferative inflammatory atrophy, the prostate cells look smaller than normal, and there are signs of inflammation in the area. Proliferative inflammatory atrophy is not cancer, but researchers believe that proliferative inflammatory atrophy may sometimes lead to high-grade PIN or to prostate cancer directly.

Prostate cancer risk groups

For prostate cancer that has not spread (stage 1 to 3 cancers), many doctors now use information about the cancer such as the T category, initial PSA level, Grade Group, and prostate biopsy results to place it into a risk group. This risk group can then be used to help determine treatment options.

Several expert groups have created risk classification systems for localized prostate cancer. One of the most commonly used systems, developed by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), divides localized prostate cancer into 6 risk groups:

- Very-low-risk group. These prostate cancers are small, not felt on exam, can only be found in a small area of the prostate, and have not grown outside the prostate (cT1c). They have a Grade Group of 1 (Gleason score of 6 or less), a low PSA level (less than 10), and few other classification criteria. These cancers usually grow very slowly and almost never cause any symptoms or other health problems.

- Low-risk group. Prostate cancers in this group have not yet grown outside of the prostate, have a Grade Group of 1 (Gleason score of 6 or less) and a low PSA level (less than 10), but they are slightly larger (cT1 to cT2a) than very-low-risk cancers. They are unlikely to cause symptoms or other health problems.

- Intermediate-risk groups (favorable or unfavorable). These prostate cancers can be felt on exam or can be seen on an imaging test. The cancer might be found in more than half of one side of the prostate (cT2b) or in both sides of the prostate (cT2c), and/or have a Grade Group of 2 or 3 (Gleason score of 7) and/or a PSA level between 10 and 20 ng/ml. Additional factors are used to split these prostate cancers into favorable intermediate-risk and unfavorable intermediate-risk categories.

- High-risk group. Prostate cancers in this group have only 1 of these high-risk features (and no very high-risk features):

- The tumor has grown outside the prostate (cT3a).

- The cancer has a Grade Group of 4 or 5 (Gleason score 8 to 10).

- The initial PSA level is more than 20.

- Very high-risk group. These prostate cancers have a very high risk for the tumor growing or spreading to nearby lymph nodes (or other parts of the body). These cancers have at least 1 of the following traits:

- The tumor has spread to the seminal vesicles (cT3b) or into other structures next to the prostate (cT4).

- The most common areas of cancer in the biopsy have a Gleason 5 pattern.

- More than 4 biopsy cores are Grade Group 4 or 5 (Gleason score 8 to 10).

- The cancer has 2 or 3 of the features found in the high-risk group (see above).

The risk group can help decide if any further tests should be done, as well as help guide treatment options. Prostate cancers in lower-risk groups have a smaller chance of growing and spreading compared to those in higher-risk groups.

If you have prostate cancer that has not spread to nearby lymph nodes or to other parts of the body, talk to your doctor about which risk group your cancer falls into.

Cambridge Prognostic Group (CPG)

In the UK, doctors divide prostate cancer into 5 prognostic groups called the Cambridge Prognostic Group (CPG). The 5 groups are from CPG 1 to CPG 5. Your Cambridge Prognostic Group (CPG) depends on 24:

- Tumor stage. This is from the T stage from the TNM staging. TNM staging system tells you about how big the cancer is and whether it has spread.

- What the cancer cells look under a microscope. This is the Grade Group or Gleason score

- Your PSA blood test level.

Below is a description of the 5 CPG groups. Ask your doctor if you have any questions about your CPG group 24:

- Cambridge Prognostic Group 1 (CPG 1). You have:

- Gleason score of 6. This is Grade Group 1;

- and a PSA level less than 10 nanograms per millilitre (ng/ml) ;

- and a T stage of 1 or 2.

- Cambridge Prognostic Group 2 (CPG 2). You have:

- Gleason score of 3 + 4 = 7. This is Grade Group 2;

- Or a PSA level between 10 and 20 ng/ml;

- and a T stage of 1 or 2.

- Cambridge Prognostic Group 3 (CPG 3). You have:

- Gleason score of 3 + 4 = 7. This is Grade Group 2;

- and a PSA level between 10 and 20 ng/ml;

- and a T stage of 1 or 2.

- OR

- Gleason score 4 + 3 = 7. This is grade group 3;

- and a T stage of 1 or 2.

- Cambridge Prognostic Group 4 (CPG 4). You have one of the following:

- Gleason score of 8. This is Grade Group 4;

- PSA level higher than 20 ng/ml;

- T stage of 3.

- Cambridge Prognostic Group 5 (CPG 5). You have two or more of the following:

- Gleason score 8. This is Grade Group 4;

- PSA level higher than 20 ng/ml;

- T stage of 3

- OR

- Gleason score 9 to 10. This is Grade Group 5

- OR

- T stage of 4.

Some doctors may still use an older system that divides prostate cancer into 3 risk groups. But the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) now recommends the CPG system instead. This is because research has found that the CPG is a more accurate way to assess prostate cancer.

- Low risk prostate cancer is similar to CPG 1.

- Medium or intermediate risk prostate cancer is similar to CPG 2 and CPG 3.

- High risk prostate cancer is similar to CPG 4 and CPG 5.

Gleason score prostate cancer prognosis

The Gleason score is essential in determining the prognosis of prostatic malignancies; however, it is not absolute 1. The Gleason score is subject to interpretation and individual pathologists vary in their evaluations and assessments 1. Artificial intelligence programs have been developed to assist in more accurate, reliable, and consistent prostate cancer grading but these are not yet in widespread use 25.

Prostate cancer with Gleason score 7 from 4+3 had worse overall survival and cancer-specific survival than Gleason score 7 from 3+4 26. Previous studies confirmed the significant difference in biochemical recurrence-free survival following radical prostatectomy between Gleason score 3+4 and 4+3 27. In a study of 263 men with pathological Gleason 7 tumor after radical prostatectomy and a median follow-up of 6.7 years, patients with Gleason score 4+3 were more likely to have seminal vesicle involvement, a higher pathological stage, extraprostatic extension, and higher median preoperative PSA, whereas the score was not independently associated with progression-free survival 28. Sakr et al. 29 found that patients with Gleason score 4+3 had a significantly higher incidence of biochemical recurrence than those with Gleason score 3+4 in the subset of patients with organ-confined prostate cancer. Chan et al. 30 investigated 570 cases of Gleason score 7 prostate cancer without lymph node metastasis, seminal vesicle invasion, or tertiary Gleason pattern, and found that a Gleason score of 4+3 was predictive of metastatic disease compared with a Gleason score of 3+4. Alenda et al. 31 found that primary Gleason pattern 4 is an independent predictor of PSA failure based on a single-center cohort of 1,248 patients with Gleason 7 tumors. Miyake et al. 32 evaluated the significance of the primary Gleason pattern in 959 consecutive Japanese male patients with Gleason score 7 prostate cancer treated with radical prostatectomy and showed that primary Gleason pattern 4 is significantly associated with the biochemical outcome.

Regarding prostate cancer associated mortality, Stark et al. 33 reported that Gleason score 4+3 is associated with a 3-fold increase in lethal prostate cancer compared with Gleason score 3+4. In this study 26, a large cohort of patients from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database and a long follow-up time were used to investigate the effects of Gleason score 3+4 and 4+3 on the overall survival and cancer-specific survival of prostate cancer. Gleason score 4+3 was associated with worse overall survival and cancer-specific survival than Gleason score 3+4 in prostate cancer patients in the multivariate Cox regression analysis and in propensity score matching analysis with other confounding factors excluded.

Other factors are also important in establishing the prognosis of prostate cancer. A rapidly increasing PSA is generally indicative of a poorer prognosis as is osteopontin expression 34. This is usually described as “PSA doubling time”. A PSA doubling time of fewer than 2 years is worrisome and suggests the need for further treatment 1. The shorter the doubling time, the higher the risk and the faster the cancer growth rate.

Physical exam findings indicating a very hard, extensive prostate, may also indicate more advanced disease and a poorer prognosis 1. Tumor staging is based on radiographic assessment (evidence of nodal or metastatic disease) and is also used to assess the prognosis 35, 36. But everything starts with the PSA level for initial cancer screening and the Gleason score as the key, initial prognostic histological classification tool 37, 38.

Prostate cancer survival rate

Survival rates tell you what percentage of people with the same type and stage of cancer are still alive a certain amount of time usually 5 years after they were diagnosed. Survival rates can’t tell you how long you will live, but they may help give you a better understanding of how likely it is that your treatment will be successful. Some men want to know the survival rates for their cancer, and some don’t. If you don’t want to know, you don’t have to.

What is a 5-year survival rate?

Statistics on the outlook for a certain type and stage of cancer are often given as 5-year survival rates, but many people live longer – often much longer – than 5 years. The 5-year survival rate is the percentage of people who live at least 5 years after being diagnosed with cancer. For example, a 5-year survival rate of 90% means that an estimated 90 out of 100 people who have that cancer are still alive 5 years after being diagnosed. Keep in mind, however, that many of these people live much longer than 5 years after diagnosis.

Relative survival rates are a more accurate way to estimate the effect of cancer on survival. These rates compare men with prostate cancer to men in the overall population. For example, if the 5-year relative survival rate for a specific stage of prostate cancer is 90%, it means that men who have that cancer are, on average, about 90% as likely as men who don’t have that cancer to live for at least 5 years after being diagnosed.

But remember, all survival rates are estimates – your outlook can vary based on a number of factors specific to you.

Cancer survival rates don’t tell the whole story

Survival rates are often based on previous outcomes of large numbers of men who had the disease, but they can’t predict what will happen in any particular man’s case. There are a number of limitations to remember:

- The numbers below are among the most current available. But to get 5-year survival rates, doctors have to look at men who were treated at least 5 years ago. As treatments are improving over time, men who are now being diagnosed with prostate cancer may have a better outlook than these statistics show.

- These statistics are based on the stage of the cancer when it was first diagnosed. They don’t apply to cancers that later come back or spread.

- The outlook for men with prostate cancer varies by the stage (extent) of the cancer – in general, the survival rates are higher for men with earlier stage cancers. But many other factors can affect a man’s outlook, such as age and overall health, and how well the cancer responds to treatment. The outlook for each man is specific to his circumstances.

Your doctor can tell you how these numbers may apply to you, as he or she is familiar with your particular situation.

Survival rates for prostate cancer

According to the most recent data, when including all stages of prostate cancer 39:

- The 5-year relative survival rate is 99%

- The 10-year relative survival rate is 98%

- The 15-year relative survival rate is 96%

Keep in mind that just as 5-year survival rates are based on men diagnosed and first treated more than 5 years ago, 10-year survival rates are based on men diagnosed more than 10 years ago and 15-year survival rates are based on men diagnosed at least 15 years ago.

In patients who undergo treatment, the most important prognostic indicators are patient age and general health at the time of diagnosis, as well as the cancer stage, pre-therapy PSA level, and Gleason score 40. A poorer prognosis is associated with higher grade disease, more advanced stage, younger age, increased PSA levels and a shorter “PSA doubling time” 41.

Prostate cancer survival rates by stage

The National Cancer Institute maintains a large national database on survival statistics for different types of cancer, known as the SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) database 42. The SEER database does not group cancers by American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM stage, but instead groups cancers into local, regional, and distant stages.

- Local stage means that there is no sign that the cancer has spread outside of the prostate. This corresponds to American Joint Committee on Cancer stages 1 and 2. About 4 out of 5 prostate cancers are found in this early stage. The relative 5-year survival rate for local stage prostate cancer is nearly 100% (>99%).

- Regional stage means the cancer has spread from the prostate to nearby areas. This includes stage 3 cancers and the stage 4 cancers that haven’t spread to distant parts of the body, such as T4 tumors and cancers that have spread to nearby lymph nodes (N1). The relative 5-year survival rate for regional stage prostate cancer is nearly 100% (>99%).

- Distant stage includes the rest of the stage 4 cancers – cancers that have spread to distant lymph nodes, bones, or other organs (M1). The relative 5-year survival rate for distant stage prostate cancer is about 37%.

Remember, these survival rates are only estimates – they can’t predict what will happen to any one man. These numbers apply only to the stage of the cancer when it is first diagnosed. They do not apply later on if the cancer grows, spreads, or comes back after treatment.

These numbers don’t take everything into account. Survival rates are grouped based on how far the cancer has spread, but your age and overall health; test results, such as the PSA level and Grade Group of the cancer; how well the cancer responds to treatment; and other factors can also affect your outlook.

Men now being diagnosed with prostate cancer may have a better outlook than these numbers show. Treatments for prostate cancer have improved over time, and these numbers are based on men who were diagnosed and treated at least 5 years earlier.

We understand that these statistics can be confusing and may lead you to have more questions. Talk with your doctor to better understand your situation.

Prostate cancer Life Expectancy

There is no clear evidence that either radical prostate surgery or radiation therapy have a significant survival advantage over the other, so treatment selection has relatively little effect on life expectancy 43.

- Patients with localized, low-grade disease (Gleason 2 + 2 = 4 or less) are unlikely to die of prostate cancer within 15 years.

- After 15 years, untreated patients are more likely to die from prostate cancer than any other identifiable disease or disorder.

- Older men with low-grade disease have approximately a 20% overall survival at 15 years, due primarily to death from other unrelated causes.

- Men with high-grade disease (Gleason 4 + 4 = 8 or higher) typically experience higher prostate cancer mortality rates within 15 years of diagnosis.

- Munjal A, Leslie SW. Gleason Score. [Updated 2023 May 1]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553178[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Zelefsky MJ, Eastham JA, Sartor AO: Cancer of the prostate. In: DeVita VT Jr, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA: Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology. 9th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2011, pp 1220-71.[↩]

- Chan TY, Partin AW, Walsh PC, Epstein JI. Prognostic significance of Gleason score 3+4 versus Gleason score 4+3 tumor at radical prostatectomy. Urology. 2000 Nov 1;56(5):823-7. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00753-6[↩]

- Zlotta AR, Egawa S, Pushkar D, Govorov A, Kimura T, Kido M, Takahashi H, Kuk C, Kovylina M, Aldaoud N, Fleshner N, Finelli A, Klotz L, Sykes J, Lockwood G, van der Kwast TH. Prevalence of prostate cancer on autopsy: cross-sectional study on unscreened Caucasian and Asian men. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013 Jul 17;105(14):1050-8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt151[↩]

- Bell KJ, Del Mar C, Wright G, Dickinson J, Glasziou P. Prevalence of incidental prostate cancer: A systematic review of autopsy studies. Int J Cancer. 2015 Oct 1;137(7):1749-57. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29538[↩]

- Hollemans E, Verhoef EI, Bangma CH, Rietbergen J, Osanto S, Pelger RCM, van Wezel T, van der Poel H, Bekers E, Helleman J, Roobol MJ, van Leenders GJLH. Cribriform architecture in radical prostatectomies predicts oncological outcome in Gleason score 8 prostate cancer patients. Mod Pathol. 2021 Jan;34(1):184-193. doi: 10.1038/s41379-020-0625-x[↩]

- Mayer R, Simone CB 2nd, Turkbey B, Choyke P. Prostate tumor eccentricity predicts Gleason score better than prostate tumor volume. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2022 Feb;12(2):1096-1108. doi: 10.21037/qims-21-466[↩]

- Gleason DF, Mellinger GT. Prediction of prognosis for prostatic adenocarcinoma by combined histological grading and clinical staging. J Urol 1974;111:58-64. 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)59889-4[↩][↩]

- Zelefsky MJ, Eastham JA, Sartor AO: Cancer of the prostate. In: DeVita VT Jr, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA: Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology. 9th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2011, pp 1220-71.[↩]

- Chan TY, Partin AW, Walsh PC, et al.: Prognostic significance of Gleason score 3+4 versus Gleason score 4+3 tumor at radical prostatectomy. Urology 56 (5): 823-7, 2000.[↩]

- Leslie SW, Soon-Sutton TL, Sajjad H, et al. Prostate Cancer. [Updated 2019 Oct 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470550[↩][↩]

- Montironi R, Santoni M, Mazzucchelli R, Burattini L, Berardi R, Galosi AB, Cheng L, Lopez-Beltran A, Briganti A, Montorsi F, Scarpelli M. Prostate cancer: from Gleason scoring to prognostic grade grouping. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2016;16(4):433-40.[↩]

- Pierorazio PM, Walsh PC, Partin AW, Epstein JI. Prognostic Gleason grade grouping: data based on the modified Gleason scoring system. BJU Int. 2013 May;111(5):753-60.[↩][↩][↩]

- Epstein JI, Amin MB, Reuter VE, Humphrey PA. Contemporary Gleason Grading of Prostatic Carcinoma: An Update With Discussion on Practical Issues to Implement the 2014 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Consensus Conference on Gleason Grading of Prostatic Carcinoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2017 Apr;41(4):e1-e7[↩]

- Pan CC, Potter SR, Partin AW, Epstein JI. The prognostic significance of tertiary Gleason patterns of higher grade in radical prostatectomy specimens: a proposal to modify the Gleason grading system. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2000 Apr;24(4):563-9.[↩]

- Thompson IM, Canby-Hagino E, Lucia MS: Stage migration and grade inflation in prostate cancer: Will Rogers meets Garrison Keillor. J Natl Cancer Inst 97 (17): 1236-7, 2005.[↩]

- Albertsen PC, Hanley JA, Barrows GH, et al.: Prostate cancer and the Will Rogers phenomenon. J Natl Cancer Inst 97 (17): 1248-53, 2005.[↩]

- PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board. Prostate Cancer Treatment (PDQ®): Health Professional Version. 2019 Sep 20. In: PDQ Cancer Information Summaries [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute (US); 2002-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK66036[↩]

- Evans JC, Malhotra M, Cryan JF, O’Driscoll CM. The therapeutic and diagnostic potential of the prostate specific membrane antigen/glutamate carboxypeptidase II (PSMA/GCPII) in cancer and neurological disease. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2016 Nov;173(21):3041-3079.[↩]

- Shen MM, Abate-Shen C. Molecular genetics of prostate cancer: new prospects for old challenges. Genes Dev. 2010 Sep 15;24(18):1967-2000.[↩]

- Liu L, Tian Z, Zhang Z, Fei B. Computer-aided Detection of Prostate Cancer with MRI: Technology and Applications. Acad Radiol. 2016 Aug;23(8):1024-46.[↩]

- Azam SH, Pecot CV. Cancer’s got nerve: Schwann cells drive perineural invasion. J. Clin. Invest. 2016 Apr 01;126(4):1242-4.[↩]

- Chen N, Zhou Q. The evolving Gleason grading system. Chin. J. Cancer Res. 2016 Feb;28(1):58-64.[↩]

- Prostate cancer risk groups and the Cambridge Prognostic Group (CPG). https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/prostate-cancer/stages/cambridge-prognostic-group-cpg[↩][↩]

- Steiner DF, Nagpal K, Sayres R, Foote DJ, Wedin BD, Pearce A, Cai CJ, Winter SR, Symonds M, Yatziv L, Kapishnikov A, Brown T, Flament-Auvigne I, Tan F, Stumpe MC, Jiang PP, Liu Y, Chen PC, Corrado GS, Terry M, Mermel CH. Evaluation of the Use of Combined Artificial Intelligence and Pathologist Assessment to Review and Grade Prostate Biopsies. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Nov 2;3(11):e2023267. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.23267. Erratum in: JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Dec 1;3(12):e2033114. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.33114[↩]

- Zhu X, Gou X, Zhou M. Nomograms Predict Survival Advantages of Gleason Score 3+4 Over 4+3 for Prostate Cancer: A SEER-Based Study. Front Oncol. 2019;9:646. Published 2019 Jul 16. doi:10.3389/fonc.2019.00646 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6646708[↩][↩]

- Epstein JI, Zelefsky MJ, Sjoberg DD, Nelson JB, Egevad L, Magi-Galluzzi C, et al. . A contemporary prostate cancer grading system: a validated alternative to the gleason score. Eur Urol. (2016) 69:428–35. 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.06.046[↩]

- Lau WK, Blute ML, Bostwick DG, Weaver AL, Sebo TJ, Zincke H. Prognostic factors for survival of patients with pathological Gleason score 7 prostate cancer: differences in outcome between primary Gleason grades 3 and 4. J Urol. (2001) 166:1692–7. 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)65655-8[↩]

- Sakr WA, Tefilli MV, Grignon DJ, Banerjee M, Dey J, Gheiler EL, et al. . Gleason score 7 prostate cancer: a heterogeneous entity? Correlation with pathologic parameters and disease-free survival. Urology. (2000) 56:730–4. 10.1016/S0090-4295(00)00791-3[↩]

- Chan TY, Partin AW, Walsh PC, Epstein JI. Prognostic significance of Gleason score 3+4 versus Gleason score 4+3 tumor at radical prostatectomy. Urology. (2000) 56:823–7. 10.1016/S0090-4295(00)00753-6[↩]

- Alenda O, Ploussard G, Mouracade P, Xylinas E, de la Taille A, Allory Y, et al. . Impact of the primary Gleason pattern on biochemical recurrence-free survival after radical prostatectomy: a single-center cohort of 1,248 patients with Gleason 7 tumors. World J Urol. (2011) 29:671–6. 10.1007/s00345-010-0620-9[↩]

- Miyake H, Muramaki M, Furukawa J, Tanaka H, Inoue TA, Fujisawa M. Prognostic significance of primary Gleason pattern in Japanese men with Gleason score 7 prostate cancer treated with radical prostatectomy. Urol Oncol. (2013) 31:1511–6. 10.1016/j.urolonc.2012.05.001[↩]

- Stark JR, Perner S, Stampfer MJ, Sinnott JA, Finn S, Eisenstein AS, et al. . Gleason score and lethal prostate cancer: does 3 + 4 = 4 + 3? J Clin Oncol. (2009) 27:3459–64. 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.4669[↩]

- Yu A, Guo K, Qin Q, Xing C, Zu X. Clinicopathological and prognostic significance of osteopontin expression in patients with prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biosci Rep. 2021 Aug 27;41(8):BSR20203531. doi: 10.1042/BSR20203531[↩]

- Gordetsky J, Epstein J. Grading of prostatic adenocarcinoma: current state and prognostic implications. Diagn Pathol. 2016 Mar 9;11:25. doi: 10.1186/s13000-016-0478-2[↩]

- Pierorazio PM, Walsh PC, Partin AW, Epstein JI. Prognostic Gleason grade grouping: data based on the modified Gleason scoring system. BJU Int. 2013 May;111(5):753-60. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11611.x[↩]

- Gleason DF. Classification of prostatic carcinomas. Cancer Chemother Rep. 1966 Mar;50(3):125-8.[↩]

- David MK, Leslie SW. Prostate-Specific Antigen. [Updated 2024 Sep 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557495[↩]

- Survival Rates for Prostate Cancer. American Cancer Society. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html[↩]

- Leslie SW, Soon-Sutton TL, Sajjad H, et al. Prostate Cancer. [Updated 2022 Feb 14]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470550[↩]

- Uchio E, Aslan M, Ko J, Wells CK, Radhakrishnan K, Concato J. Velocity and doubling time of prostate-specific antigen: mathematics can matter. J Investig Med. 2016 Feb;64(2):400-4. doi: 10.1136/jim-2015-000008[↩]

- Prostate Cancer — Cancer Stat Facts. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/prost.html[↩]

- Hawken SR, Auffenberg GB, Miller DC, Lane BR, Cher ML, Abdollah F, Cho H, Ghani KR; Michigan Urological Surgery Improvement Collaborative. Calculating life expectancy to inform prostate cancer screening and treatment decisions. BJU Int. 2017 Jul;120(1):9-11. doi: 10.1111/bju.13812[↩]