Peritoneal carcinomatosis

Peritoneal carcinomatosis also called metastatic cancer to the peritoneum is a condition where cancer cells from another organ spread to the peritoneum, the lining of the abdominal cavity and is often considered an advanced stage of cancer or stage 4 cancer. The peritoneum is a thin membrane that lines your abdominal cavity, covering your stomach, liver, and bowel. Cancer cells break off from the original site where cancer begins (primary tumor) such as from the colon, ovaries, stomach, and appendix, then these cells then travel and implant on the surface of the peritoneum, which has a large surface area and rich blood supply. Peritoneal carcinomatosis can result from cancers of the gastrointestinal, reproductive and genitourinary tracts such as the ovary, colon, stomach, or appendix, or from primary peritoneal cancers like mesothelioma 1. Ovarian, colon, and gastric cancers are by far the most common conditions presenting in advanced stages with peritoneal metastasis. Cancers involving other organs such as the pancreas, appendix, small intestine, endometrium, and prostate can also cause peritoneal metastasis, but such occur less frequently. While peritoneal carcinomatosis can arise from extra-abdominal primary cancers, such cases are uncommon; and they account for approximately 10% of diagnosed cases of peritoneal metastasis 2. Examples include breast cancer, lung cancer, and malignant melanoma. Ovarian cancer is the most common cancer causing peritoneal metastasis in 46% of cases owing to the anatomic location of the ovaries and their close contact with the peritoneum as well as the embryological developmental continuity of ovarian epithelial cells with peritoneal mesothelial cells 3.

- Colorectal cancer patients also contribute to a higher number of patients with peritoneal involvement due to the high incidence of these cancers overall. About 7% of cases develop synchronous peritoneal metastasis 4.

- Approximately 9% of non-endocrinal pancreatic cancer cases present with peritoneal cancer.

- Gastric carcinoma tends to reach an advanced stage at first presentation, and 14% of such cases can have peritoneal metastasis 5.

- A neuroendocrine tumor arising from the gastrointestinal tract (GI-NET) is a slow-growing neoplasm, and it can metastasize to the peritoneum. peritoneal cancer can occur in about 6% of gastrointestinal-neuroendocrine tumor patients 6. Its frequency increases with age.

- Peritoneal carcinomatosis from extra-abdominal malignancy presents in only 10% of cases, where metastatic breast cancer (41%), lung cancer (21%) and malignant melanoma (9%) account for the majority of the cases 2.

- Lung cancer is the primary cause of newly diagnosed cancers worldwide accounting for over a million new cases per year. However, peritoneal carcinomatosis in lung cancer is rare and occurs in about 2.5 to 16% of autopsy results. Considering the scale of lung cancer rates globally, it could be the reason for a higher number of peritoneal carcinomatosis cases worldwide 7.

- Sometimes it is difficult to find the primary tumor site. In such cases, we have peritoneal carcinomatosis with an unknown primary. About 3 to 5% of cases of peritoneal carcinomatosis are of unknown origin 8.

Some people may notice symptoms of peritoneal carcinomatosis early, while others may not feel anything until the peritoneal carcinomatosis has gotten worse. Symptoms often become more noticeable when cancer cells grow and start affecting nearby organs, such as your intestines, bladder and stomach.

Peritoneal carcinomatosis signs and symptoms may include:

- Early stage: Often vague or absent, sometimes mistaken for other conditions.

- Later stage:

- Abdominal welling or bloating. This is the most common symptom. Swelling is caused by fluid buildup, called ascites, in your belly. You may feel that you’re is gaining weight in your abdomen despite exercise. Women in menopause may appear as if they are pregnant.

- Fluid buildup in your abdomen (ascites) leading to a swollen abdomen, fatigue, and shortness of breath.

- Abdominal pain or discomfort. This is often described as vague cramping or pressurelike pain.

- Nausea and vomiting. These are often linked to bowel issues caused by tumor pressure.

- Constipation or diarrhea and, sometimes, a blockage that prevents food or gas from passing.

- Unexplained weight loss or gain. Losing weight without trying is not related to changes in diet or activity.

- A feeling of fullness.

- Loss of appetite. Someone may feel full quickly, even after small meals.

- Fatigue. Someone may feel very tired, even after resting.

- Bleeding. Peritoneal carcinomatosis may cause rectal or vaginal bleeding.

Other possible symptoms include:

- Urinary symptoms. If cancer spreads near your bladder or ureters, it may cause changes in urination or block urine flow. The urinary bladder is a hollow, muscular, and stretchy organ located in the lower abdomen that temporarily stores urine from the kidneys before it is expelled from the body. The ureters are thin tubes that carry urine from each kidney to the bladder.

- Shortness of breath. This is usually due to pressure from fluid buildup pushing on the lungs.

Peritoneal carcinomatosis often spreads across the abdominal lining without forming distinct masses. Because of this, doctors usually need to combine imaging, fluid tests, and sometimes surgery, to confirm a diagnosis.

Peritoneal carcinomatosis diagnosis may include:

- Imaging tests. Imaging tests such as CT, MRI and PET scans are typically the first step in looking for suspected peritoneal carcinomatosis. These scans help identify visible tumor spread, fluid buildup or organ involvement. However, imaging is often not sensitive enough to detect smaller cancers or early peritoneal disease. Therefore, a negative scan does not rule out peritoneal carcinomatosis.

- Biopsy of tissue from the peritoneum. A peritoneal biopsy is a procedure to remove a tissue sample from the peritoneum, the lining of your abdomen, for microscopic examination. It is used to diagnose conditions like peritoneal mesothelioma and can be performed using techniques such as a laparoscopy (keyhole surgery) or a CT-guided/ultrasound-guided core biopsy. The chosen method depends on your health, the location of the suspicious tissue, and the suitability for sampling.

- Peritoneal washing cytology. In this test, fluid from the abdominal cavity is surgically collected during a minor procedure. It’s then examined under a microscope. Doctors use peritoneal washing cytology to check for cancer cells floating in the peritoneal fluid. Even when no visible cancer is present, a positive cytology result is a strong sign that peritoneal spread has happened.

- Staging laparoscopy. Staging laparoscopy (keyhole surgery) is a safe, minimally invasive surgical procedure used to look directly inside the abdominal cavity using a small camera. It allows your doctor to inspect the peritoneum, find hidden tumors, and take tissue or fluid samples. This test is especially valuable for finding peritoneal metastases that are too small to be seen with imaging.

- Tumor marker tests. Tumor marker tests use a sample of blood to look for chemicals made by cancer cells e.g. CEA, CA 19-9, CA 125.

- Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA). This is a newer blood test that looks for small pieces of DNA from cancer cells in the blood. It can help find peritoneal cancer that doesn’t show up on scans. However, the role of ctDNA in diagnosis is still uncertain.

Sometimes metastatic cancer to the peritoneum is diagnosed during surgery for another issue or for another abdominal cancer.

Carcinomatosis of peritoneum treatment may include:

- Systemic chemotherapy: Systemic chemotherapy is a cancer treatment that uses drugs, delivered through the bloodstream, to reach and attack cancer cells throughout the entire body, often used to shrink tumors before surgery or to manage symptoms. Unlike local treatments, systemic chemo can treat cancer that has spread to distant organs or lymph nodes. These drugs can be administered via intravenous (IV) infusion, injection, or as oral pills.

- Targeted therapy: Targeted therapy is a type of cancer treatment that uses drugs to block the growth and spread of cancer by interfering with specific molecules, or “molecular targets”, involved in cancer growth. Unlike traditional chemotherapy, it is designed to attack cancer cells while causing less damage to healthy cells by targeting key differences between the two. These therapies can work by blocking growth signals, stopping blood vessel growth to the tumor, or delivering toxins directly to the cancer cells. Uses drugs to specifically target and control cancer cell growth.

- Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) also known as debulking surgery: Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) is a surgical procedure to remove cancerous tumors from the abdomen and pelvic cavity that have spread to the peritoneum. Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) is often performed alongside heated intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC), where hot chemotherapy is circulated in the abdomen to kill any remaining microscopic cancer cells. The goal of cytoreductive surgery (CRS) is to completely remove all visible tumors, and the surgery may involve removing other affected organs as well.

- Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC): Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) is a two-stage cancer treatment for advanced abdominal cancers that combines surgery to remove tumors with the administration of heated chemotherapy drugs directly into your abdominal cavity. After visible tumors are surgically removed, a heated chemotherapy solution is circulated throughout your abdomen for a short period, typically 90 minutes to two hours to kill any remaining microscopic cancer cells, reducing the risk of recurrence.

- Other treatments: Depending on your situation, other methods like Pressurized Intraperitoneal Aerosol Chemotherapy (PIPAC) may be used for patients who cannot undergo surgery. Pressurized Intraperitoneal Aerosol Chemotherapy (PIPAC) is a minimally invasive surgical technique that delivers low-dose chemotherapy as a pressurized aerosol directly into your abdominal cavity to treat cancers that have spread to the peritoneum. Pressurized Intraperitoneal Aerosol Chemotherapy (PIPAC) offers advantages like improved drug distribution, deeper tissue penetration, and reduced systemic side effects compared to traditional chemotherapy. Pressurized Intraperitoneal Aerosol Chemotherapy (PIPAC) is currently considered a palliative treatment for managing symptoms in patients with peritoneal metastases who are not candidates for curative surgery.

Historically, the presence of metastatic deposits in the peritoneal cavity implied an incurable, fatal disease where curative surgical therapy was no longer a reasonable option. Newer surgical techniques and innovation in medical management strategies, for example a combination of cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC), have dramatically changed the course of the disease over the past years. Effective treatment approaches have evolved, allowing for improvements in disease-free and overall survival 9.

Figure 1. Peritoneal carcinomatosis from advanced gastric cancer

Footnotes: A 40-year-old man with advanced stomach cancer and peritoneal carcinomatosis. Axial portal venous phase CT images revealed multifocal discrete nodules (arrowheads) in the peritoneal cavity, peritoneal enhancement and thickening (arrow), ascites, and omental haziness (open arrow). Note the metastatic lymphadenopathy around the stomach (open arrowheads).

[Source 10 ]Figure 2. Ovarian cancer with peritoneal carcinomatosis

Footnotes: Non-intravenous contrast CT abdomen demonstrating multiple peritoneal masses with ascites. Normal ovaries not visualized in this study. The non-intravenous contrast CT abdomen, only confirmed peritoneal masses. Further imaging is required to characterize these lesions. In this case, the patient was confirmed as ovarian cancer with peritoneal carcinomatosis.

[Source 11 ]Figure 3. Peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer

Footnotes: 50 year old man with mid abdominal pain. CT show medium amount of abdominal ascites with thickening and nodularity of the omentum forming an omental cake. Few areas of subtle nodularity in the peritoneum, for example right paracolic gutter. Thickening and irregularity of the distal descending/proximal sigmoid colon, without obstruction. Several low-attenuation hepatic lesions. Small right and trace left pleural effusions. In the absence of a known primary tumor, ultrasound-guided biopsy of the omentum can be safely performed to obtain tissue diagnosis. Pathologic diagnosis of moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma.

[Source 12 ]Figure 4. Peritoneal carcinomatosis from breast cancer

Footnotes: A 50-year-old woman with a history of breast cancer presented with increasing abdominal distension and discomfort. Some nausea. CT show extensive fluid is seen in the peritoneal cavity associated with thickening of the peritoneum which enhances and appears nodular in places. The omentum, located anteriorly and to the left of the midline, appears stranded and bulky with multiple nodular regions of soft tissue density. Nodular pleural thickening is noted on the left, and bilateral breast prostheses in situ. On the right side of the T12 vertebral body, involving the posterior vertebral body and right pedicle, is a region of mixed sclerosis and lysis. Similar other regions are present elsewhere in the spine (confirmed on bone window – not shown).

[Source 13 ]Figure 5. Primary peritoneal carcinoma

Footnotes: Computed tomography scan revealing abundant ascites and omental infiltration. The white arrow indicates omental infiltration.

[Source 14 ]What is the peritoneum?

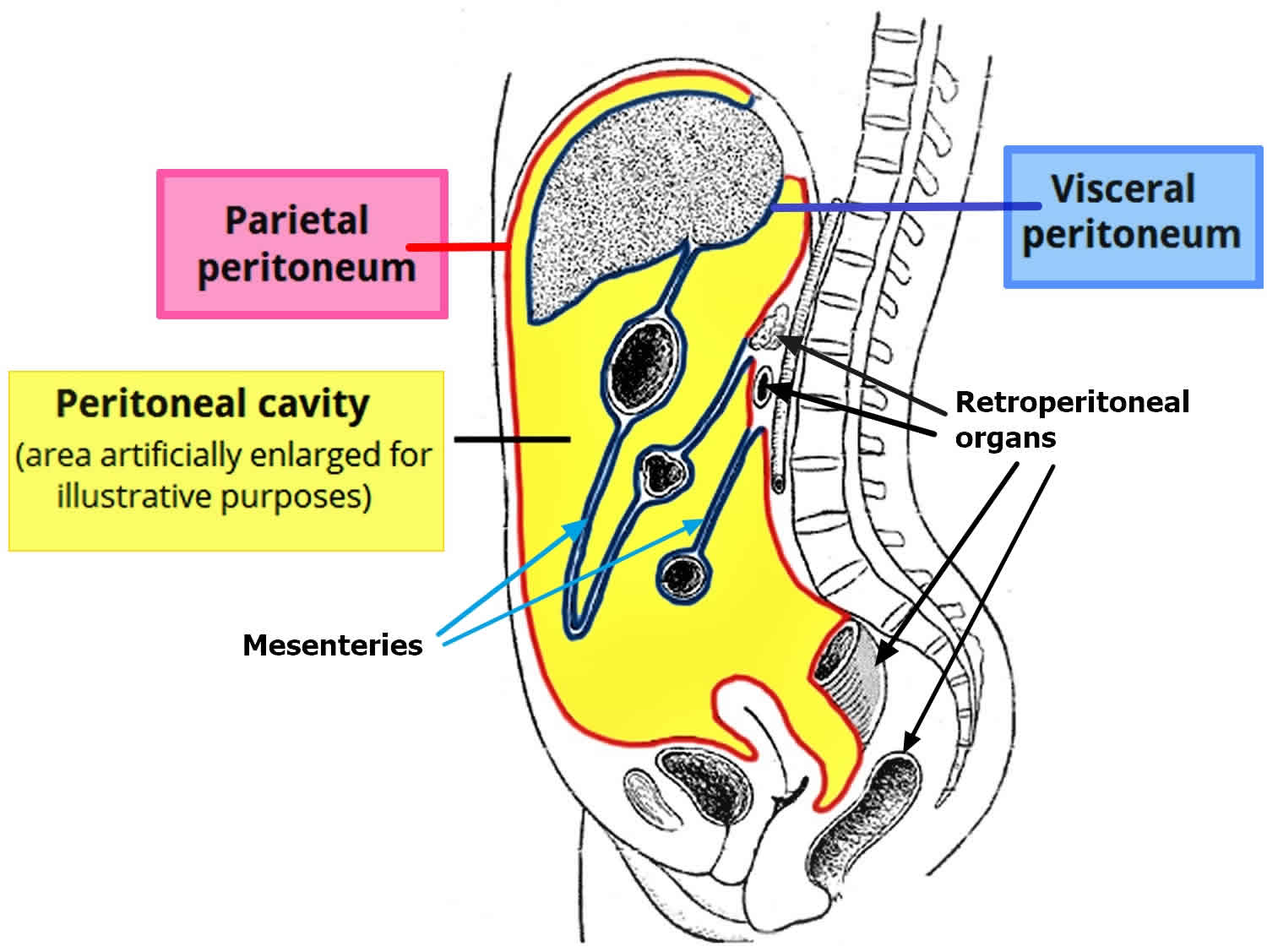

The peritoneum covers all of the organs within your tummy (abdomen), such as the bowel and the liver. The peritoneum protects the organs and acts as a barrier to infection. The peritoneum has 2 layers. One layer lines the abdominal wall and is called the parietal layer. The other layer covers the organs and is called the visceral layer.

There is a small amount of fluid between the two layers, which separates them and allows them to slide over each other. This fluid allows us to move around without causing any friction on the layers.

Footnotes: Drawing of the peritoneal cavity illustrating the flow of peritoneal fluid (arrows) and frequent locations for peritoneal seeding (closed stars).

Abbreviations: L = liver; LS = lesser sac; S = spleen; TC = transverse mesocolon; PCL = phrenicocolic ligament; AC = ascending colon; DC = descending colon; SM = small bowel mesentery; SC = sigmoid mesocolon; R = rectum.

[Source 10 ]Peritoneal carcinomatosis causes

Peritoneal carcinomatosis develops when cancer cells break off from the original site where cancer begins (primary tumor) such as from the colon, ovaries, stomach, and appendix. The cancer cells then travel into the abdominal cavity and attach to the lining of the belly called the peritoneum. The peritoneum has a large surface area with a rich blood supply. This allows cancer cells to grow quickly. Peritoneal carcinomatosis is often considered an advanced stage of cancer or stage 4 cancer.

The most common cancers that can lead to peritoneal carcinomatosis include 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20:

- Ovarian cancer.

- Colon or rectal cancer (colorectal cancer).

- Stomach cancer.

- Pancreatic cancer.

- Appendix cancer.

- Less commonly, breast, lung, melanoma, esophageal, gallbladder, liver, cholangiocarcinoma, neuroendocrine, endometrial, skin cancer, gastrointestinal stromal tumors or urothelial carcinoma of the urinary tract.

Cancer that starts in the peritoneum is called primary peritoneal cancer. This is much rarer than peritoneal carcinomatosis that has spread from other organs, which is considered a secondary or metastatic cancer. The most common primary peritoneal cancer is peritoneal mesothelioma.

Risk factors for peritoneal carcinomatosis

Most of the time, peritoneal carcinomatosis happens when cancer spreads to the peritoneum from the original site where cancer begins (primary tumor) such as from the colon, ovaries, stomach, and appendix. Some traits of the cancer or the person can make the cancer more likely to spread to the peritoneum.

- Advanced or larger cancers. Cancers that grow through the outermost layers of the organs or spread to lymph nodes are more likely to reach the peritoneum.

- Certain types of cancer cells. Some cancer cells, including mucinous and signet ring cancer cells, are strongly linked to peritoneal carcinomatosis. These types of cancers can be fast growing and aggressive and are more likely to spread throughout the abdomen rather than stay in one spot. That raises the risk that they will cause peritoneal carcinomatosis.

- Lymph node involvement. When cancer has already spread to nearby lymph nodes, the risk of peritoneal carcinomatosis is higher.

- Surgery to remove primary cancer. Having surgery to remove primary cancer in nearby organs increases the risk of cancer cells spreading during the procedure. If the cancerous tissue is accidentally cut or leaks during surgery, cancer cells can spill into the abdominal cavity. These cells can implant on the peritoneum and grow into new cancers.

- Cancer location. Cancers on the right side of the colon are more likely to spread to the peritoneum than are cancers on the left side of the colon.

Peritoneal carcinomatosis signs and symptoms

Some people may notice symptoms of peritoneal carcinomatosis early, while others may not feel anything until the peritoneal carcinomatosis has gotten worse. Symptoms often become more noticeable when cancer cells grow and start affecting nearby organs, such as your intestines, bladder and stomach.

Peritoneal carcinomatosis signs and symptoms may include:

- Early stage: Often vague or absent, sometimes mistaken for other conditions.

- Later stage:

- Abdominal welling or bloating. This is the most common symptom. Swelling is caused by fluid buildup, called ascites, in your belly. You may feel that you’re is gaining weight in your abdomen despite exercise. Women in menopause may appear as if they are pregnant.

- Fluid buildup in your abdomen (ascites) leading to a swollen abdomen, fatigue, and shortness of breath.

- Abdominal pain or discomfort. This is often described as vague cramping or pressurelike pain.

- Nausea and vomiting. These are often linked to bowel issues caused by tumor pressure.

- Constipation or diarrhea and, sometimes, a blockage that prevents food or gas from passing.

- Unexplained weight loss or gain. Losing weight without trying is not related to changes in diet or activity.

- A feeling of fullness.

- Loss of appetite. Someone may feel full quickly, even after small meals.

- Fatigue. Someone may feel very tired, even after resting.

- Bleeding. Peritoneal carcinomatosis may cause rectal or vaginal bleeding.

Other possible symptoms include:

- Urinary symptoms. If cancer spreads near your bladder or ureters, it may cause changes in urination or block urine flow. The urinary bladder is a hollow, muscular, and stretchy organ located in the lower abdomen that temporarily stores urine from the kidneys before it is expelled from the body. The ureters are thin tubes that carry urine from each kidney to the bladder.

- Shortness of breath. This is usually due to pressure from fluid buildup pushing on the lungs.

Peritoneal carcinomatosis complications

Peritoneal carcinomatosis can lead to several serious complications as the cancer spreads and affects organs within the abdominal cavity:

- Fluid buildup in the belly a condition called ascites. Cancer cells in the peritoneum often cause fluid to build up in your belly. This leads to bloating, discomfort, shortness of breath and, sometimes, infection. Fluid may need to be drained often, sometimes through catheters that you or your caregiver can manage at home.

- Bowel blockage. As cancer spreads across the peritoneum, it can press on or wrap around your intestines. This can lead to a bowel obstruction. This can cause severe pain and vomiting and make it difficult to pass stool or eat. Bowel obstructions may require emergency surgeries.

- Urinary blockage. In peritoneal carcinomatosis, cancer can press on or grow around the thin tubes called ureters that carry urine from each kidney to the bladder. This can block the flow of urine.

- Trouble absorbing nutrients. When the intestines aren’t working well, your body can’t take in enough nutrients from food. Over time, this can make you malnourished, weak and raise the risk of conditions such as infections or poor nutrition.

Peritoneal carcinomatosis diagnosis

Peritoneal carcinomatosis often spreads across the abdominal lining without forming distinct masses. Because of this, doctors usually need to combine imaging, fluid tests, and sometimes surgery, to confirm a diagnosis.

Peritoneal carcinomatosis diagnosis may include:

- Imaging tests. Imaging tests such as CT, MRI and PET scans are typically the first step in looking for suspected peritoneal carcinomatosis. These scans help identify visible tumor spread, fluid buildup or organ involvement. However, imaging is often not sensitive enough to detect smaller cancers or early peritoneal disease. Therefore, a negative scan does not rule out peritoneal carcinomatosis.

- Biopsy of tissue from the peritoneum. A peritoneal biopsy is a procedure to remove a tissue sample from the peritoneum, the lining of your abdomen, for microscopic examination. It is used to diagnose conditions like peritoneal mesothelioma and can be performed using techniques such as a laparoscopy (keyhole surgery) or a CT-guided/ultrasound-guided core biopsy. The chosen method depends on your health, the location of the suspicious tissue, and the suitability for sampling.

- Peritoneal washing cytology. In this test, fluid from the abdominal cavity is surgically collected during a minor procedure. It’s then examined under a microscope. Doctors use peritoneal washing cytology to check for cancer cells floating in the peritoneal fluid. Even when no visible cancer is present, a positive cytology result is a strong sign that peritoneal spread has happened.

- Staging laparoscopy. Staging laparoscopy (keyhole surgery) is a safe, minimally invasive surgical procedure used to look directly inside the abdominal cavity using a small camera. It allows your doctor to inspect the peritoneum, find hidden tumors, and take tissue or fluid samples. This test is especially valuable for finding peritoneal metastases that are too small to be seen with imaging.

- Tumor marker tests. Tumor marker tests use a sample of blood to look for chemicals made by cancer cells e.g. CEA, CA 19-9, CA 125.

- Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA). This is a newer blood test that looks for small pieces of DNA from cancer cells in the blood. It can help find peritoneal cancer that doesn’t show up on scans. However, the role of ctDNA in diagnosis is still uncertain.

Sometimes metastatic cancer to the peritoneum is diagnosed during surgery for another issue or for another abdominal cancer.

Peritoneal carcinomatosis differential diagnosis

Peritoneal carcinomatosis differential diagnosis includes conditions that mimic peritoneal carcinomatosis appearance on imaging, such as other primary or metastatic peritoneal cancers (like peritoneal mesothelioma), infectious and inflammatory processes (tuberculosis, actinomycosis, endometriosis), and benign conditions (pseudomyxoma peritonei, desmoid tumors, splenosis implants) 10, 21, 22, 23, 24. Distinguishing between these conditions is crucial and often involves evaluating imaging findings on CT or MRI, considering patient history, and sometimes using tumor markers or biopsy.

Neoplastic mimics

- Primary peritoneal cancers: Conditions like primary peritoneal mesothelioma or primary peritoneal lymphomatosis.

- Other metastatic cancers: The spread of a tumor from a different organ, which is a key feature of carcinomatosis, can appear similar on imaging.

- Benign tumors: Certain benign growths, such as desmoid tumors, can present as masses in the peritoneal cavity.

- Pseudomyxoma peritonei: A condition of mucinous tumors that can spread within the peritoneal cavity, often mimicking carcinomatosis.

Inflammatory and infectious mimics

- Tuberculous peritonitis: An infection that can cause inflammation and thickening of the peritoneum, presenting with symptoms and imaging findings that overlap with peritoneal cancer.

- Granulomatous peritonitis: An inflammatory reaction caused by infections like histoplasmosis.

- Endometriosis: Tissue from the uterine lining that grows outside the uterus, most commonly in the pelvic peritoneum, which can mimic peritoneal implants.

- Actinomycosis: A bacterial infection that can cause chronic inflammation.

Other conditions

- Gliomatosis peritonei: A rare condition where glial cells spread to the peritoneum, usually associated with ovarian teratomas.

- Desmoid tumors: Benign but locally aggressive fibrous tumors.

- Solitary fibrous tumors: A rare tumor that can occur in various locations, including the peritoneum.

- Splenosis implants: The accidental implantation of splenic tissue elsewhere in the body after a trauma or surgery involving the spleen.

Peritoneal carcinomatosis treatment

Peritoneal carcinomatosis treatment often requires a combination of therapies. The exact plan depends on where the cancer started, how far it has spread and your overall health. Your doctor also considers your treatment goals, such as extending your life, symptom relief or both. Recent advancements in surgical techniques and favorable outcomes related to targeted chemotherapy have encouraged the aggressive treatment of peritoneal cancer whenever it is feasible and accessible. Complete cytoreductive surgery (CRS) combined with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) and systemic chemotherapy has become the mainstay treatment for peritoneal carcinomatosis (peritoneal cancer) originating from most gastrointestinal and genitourinary tracts carcinomas. The efficacy of this treatment was validated in 2003 by a randomized clinical trial that compared complete cytoreductive surgery combined with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) versus systemic chemotherapy alone (median survival: 22.3 vs. 12.6 months) 25. Macroscopically complete complete cytoreductive surgery (CRS-R0) is a major prognostic factor, with 5-year survival rates as high as 45% compared to less than 10% when complete cytoreductive surgery is incomplete 26. Dr. Sugarbaker 27 changed the perception relating to peritoneal carcinomatosis from being terminal cancer to being a loco-regional disease and recommended an aggressive surgical approach with complete cytoreductive surgery, given the positive survival benefits.

Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) are complex procedures that require extensive support and and should only be done in centers with experience. Careful patient selection is crucial to achieve good outcomes. It’s best for people who are healthy enough for surgery and whose cancer can be mostly or completely removed.

The first step in the management centers on appropriate patient selection for surgery.

Patient selection:

- Patient characteristics: age, co-morbidities, general condition, and functional status. The objective is to determine the fitness of the patient for the anticipated trauma of surgery and its perioperative impact.

- Exclude generalized metastatic disease: As pointed in the diagnostic section, CT and/or MRI or sometimes PET/CT can be used to investigate potential distal metastases depending on the type of cancer. Possible sites to look for are thorax, spine bones, brain, etc.

- The extent of the peritoneal disease.

CT/MRI is the primary investigation tool to determine the size, extent, and type of peritoneal lesions. Peritoneal cancer scoring system also known as Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) or the Sugarbaker score described in Figure 7 is routinely used to determine the surgical resectability and possibly favorable prognosis 28, 29, 30.

The Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) is a numerical score used to quantify the extent of cancer spread throughout the abdomen and pelvis. The Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) is determined during surgery by dividing the abdomen into 13 regions, scoring each from 0 to 3 based on tumor size, and summing the scores for a total Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) value 30, 29, 31. A lower Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) indicates less extensive disease and is associated with a better prognosis and a higher likelihood of successful complete cytoreductive surgery, while a higher Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) suggests more widespread disease.

How Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) is calculated 29, 31, 28:

- The abdomen and pelvis are divided into 13 regions.

- 0. Central.

- 1. Right upper.

- 2. Epigastrium.

- 3. Left upper.

- 4. Left flank.

- 5. Left lower.

- 6. Pelvis.

- 7. Right lower.

- 8. Right flank.

- 9. Upper jejunum.

- 10. Lower jejunum.

- 11. Upper ileum.

- 12. Lower ileum.

- Each region is assigned a score from 0 to 3, based on the size of the largest tumor in that region:

- 0: No tumor

- 1: Tumor implants up to 0.5 cm

- 2: Tumor implants between 0.5 cm and 5 cm

- 3: Tumor implants larger than 5 cm or clusters of implants

The scores from all 13 regions are added together to get a total Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) score. The sum of the scores of all regions gives the total Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) value, which can vary between 0 and 39.

What the Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) score means:

- Lower Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) ≥ 20: Indicates limited disease spread and is associated with a better prognosis and a higher chance of achieving complete cytoreductive surgery. These patients are optimal candidates for cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (CRS/HIPEC).

- Higher Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) >20: Is associated with more widespread disease and a lower chance of achieving complete cytoreductive surgery.

- Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) of 20-30 still represents potentially resectable disease for some patients. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy may be used before CRS/HIPEC to help shrink the tumour volume. Outcomes begin to decrease more rapidly above a PCI of 25.

- Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) above 30-40 typically means the cancer has spread too extensively throughout the peritoneum to be fully resected surgically. Palliative management focusing on symptom relief usually provides the best option at this point rather than cure-directed treatment.

A higher Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) is a negative prognostic factor especially in cancers like ovarian cancer, colorectal cancer, and pseudomyxoma peritonei, meaning it is associated with poorer survival outcomes.

The Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) helps surgeons decide if a complete removal of the tumor is possible and if the patient is a good candidate for procedures like cytoreductive surgery combined with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (CRS-HIPEC).

Some studies use Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) categories of: 0-10 (very limited), 10-20 (limited), 20-30 (moderate), and over 30 (extensive). These provide a simplified way of stratifying patients into prognosis groups to help guide treatment decisions and set goals.

Changes in Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) over the course of treatment and follow-up indicate how well the cancer is being controlled. A declining Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) shows the therapy is working, while a rising PCI suggests progressive disease and treatment failure. Close monitoring Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) is used to detect recurrence early.

Diagnostic laparoscopy provides very accurate estimates for Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) along with probable completeness of the cytoreduction (CC) index and outcome assessment in terms of disease-free survival, overall survival and quality of life. Involvement of the small bowel impacts the peritoneal cancerI score and can suggest a bad prognosis. The following are the usual surgical sites used for preoperative determination of the extent of the disease for exclusion from complete cytoreductive surgery 32:

- Massive mesenteric root infiltration not amenable to complete cytoreduction

- Significant pancreatic capsule infiltration or pancreatic involvement requiring major resection not feasibly or amenable to complete surgical cytoreduction

- More than one-third small bowel length involvement requiring resection

- Extensive hepatic metastasis

Some surgeons advocate the use of peritoneal surface disease severity score (PSDSS) for the early preoperative assessment of the prognosis based on the symptoms, peritoneal cancerI index, and Primary tumor histology. However, extensive study results are needed to implement it on a regular practice 32.

Figure 7. Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) scoring system (Sugarbaker score)

Footnotes: Sugarbaker’s Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) is a numerical score that is determined during surgery and it is used to quantify the extent of cancer spread throughout the abdomen and pelvis. The abdominal cavity is divided into 13 regions (from 0 to 12). A score of 0 to 3 is assigned to each of these regions depending on tumor size found there (0: no lesion; 1: lesion ≤ 0.5 cm; 2: lesions ≤ 5 cm; 3: lesions > 5 cm). The sum of these scores produces the PCI, ranging from 1 to 39.

[Source 30 ]Systemic chemotherapy

Systemic chemotherapy is most common treatment for peritoneal carcinomatosis. This is medicine given through the blood to reach the whole body. Chemotherapy uses strong medicines to kill cancer cells, help shrink tumors, and relieve symptoms such as pain or bloating. Chemotherapy also may allow for surgery later. However, systemic chemotherapy doesn’t reach the peritoneum as well as it does other parts of your body, which can limit how well it works for peritoneal carcinomatosis.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is a type of cancer treatment that uses the body’s own immune system to fight cancer by helping it recognize and attack cancer cells. Immunotherapy works by stimulating a stronger immune response or by making it easier for immune cells to find and destroy cancer cells. This treatment can be used alone or with other cancer treatments, and there are different types, such as oncolytic virus therapy, checkpoint inhibitors, and CAR T-cell therapy. Immunotherapy is another type of systemic treatment that may be offered for certain cancers.

Cytoreductive surgery (CRS)

Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) also known as debulking surgery is a surgical procedure to remove all visible cancerous tumors from the abdomen and pelvic cavity that have spread to the peritoneum (the lining of the abdominal cavity) 33. Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) is often combined with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC), where a heated chemotherapy solution is circulated in the abdomen after the surgery to kill any remaining microscopic cancer cells 33. The goal of cytoreductive surgery (CRS) is to completely remove all visible tumors, and the surgery may involve removing other affected organs as well. Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) is a major operation used to manage selected patients with metastatic cancers from the peritoneum, such as those originating from colorectal, appendiceal, ovarian, or stomach cancers. The procedure can take several hours (4 to 10 hours). Patients often have a hospital stay of about 7 to 10 days. Recovery is a major process, and some patients may experience long-term gastrointestinal issues, fatigue, or depression.

Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) are complex procedures that require extensive support and and should only be done in centers with experience. Careful patient selection is crucial to achieve good outcomes. It’s best for people who are healthy enough for surgery and whose cancer can be mostly or completely removed.

How cytoreductive surgery (CRS) works:

- Cytoreductive surgery (CRS): The surgeon removes all visible tumors and affected tissues, such as parts of the bowel, gallbladder, or spleen, to reduce the amount of cancer in your body.

- Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC): After the visible tumors are removed, the abdominal cavity is filled with a heated chemotherapy solution for a period to kill any remaining microscopic cancer cells. The heat helps to increase the chemotherapy’s effectiveness and can deliver a higher local dose than systemic chemotherapy.

Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) benefits:

- Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) is a major operation that removes all visible cancer from the peritoneum and other organs in the abdomen.

- Can improve quality of life and increase survival rates for selected patients.

- Helps relieve symptoms associated with the cancer.

- May reduce tumor recurrence rates.

Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) risks:

Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) risks are similar to other major abdominal surgeries and can include bleeding, wound infection, blood clots, breathing difficulties, bowel obstruction, peritonitis and potential kidney failure. There is also a risk of allergic reaction to the chemotherapy drug.

Contraindications for cytoreductive surgery (CRS) include a Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) score >17 in colorectal-associated peritoneal cancer and Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) >12 in gastric cancer 21. Tumor involvement of critical anatomic sites in the abdomen and multiple extra-abdominal metastatic lesions also preclude cytoreductive surgery (CRS) 34.

Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC)

Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) is a surgical cancer treatment that involves removing tumors from the abdominal cavity and then flooding the area with heated chemotherapy drugs to kill any remaining cancer cells 33, 35. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) is a two-stage procedure performed after the surgical removal of visible tumors, and it aims to reduce the risk of cancer recurrence by treating microscopic cancer cells within the peritoneal cavity. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) is a major procedure with risks, and eligibility depends on factors like cancer type, spread, and overall health. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) is used for certain advanced abdominal cancers, such as those of the appendix, colon, stomach, pancreas, ovaries, peritoneum and mesothelioma.

Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) is typically combined with cytoreductive surgery (CRS). After the cancer is removed during surgery, the abdominal cavity is bathed with heated chemotherapy to target any remaining microscopic cancer cells. This combined approach, often referred to as CRS-HIPEC or HIPEC surgery, allows for higher medicine concentrations to reach cancer in the peritoneum. This can lessen the typical side effects people often have with systemic chemotherapy due to less absorption in the bloodstream.

Research has shown that HIPEC can prevent cancer from returning for certain people whose cancer has spread to the abdominal cavity. Therefore, HIPEC may prolong survival.

How hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) works:

- Surgical tumor removal: The first step is a surgery called cytoreductive surgery, where visible tumors are surgically removed from the abdomen.

- Heated chemotherapy: A heated chemotherapy solution is then pumped directly into the abdominal cavity through catheters.

- Circulation and temperature: The heated chemotherapy solution is circulated for about 90 minutes to 2 hours, often with the patient being physically rocked to ensure the drug reaches all areas of the cavity. The temperature is typically around 108 °F (42 °C).

- Draining: The solution is then drained from the abdomen, and the incisions are closed.

Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) has several advantages over standard chemotherapy:

- It is a single treatment done in the operating room, instead of multiple treatments over several weeks

- 90% of the drug stays within the abdominal cavity, decreasing toxic effects on the rest of the body

- It allows for a more intense dose of chemotherapy.

Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) provides a high, targeted dose of chemotherapy directly to cancer cells in your abdomen. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) may offer a survival benefit for certain patients and reduces the risk of cancer recurrence.

Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) side effects:

Side effects of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) are similar to those experienced after major surgery and standard chemotherapy, and can include:

- Nausea and vomiting

- Electrolyte abnormalities

- Brief worsening of kidney function

Complication related to hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC):

- Oxaliplatin is used with dextrose solutions, so it could potentially contribute to postoperative acidosis and hyperglycemia

- Mitomycin C can cause neutropenia in about one-third of patients

- Other gastrointestinal side effects.

Early Postoperative Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy (EPIC)

Early Postoperative Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy (EPIC) is a cancer treatment that uses chemotherapy drugs delivered directly into the abdomen (intraperitoneal) in the days following surgery 36, 37, 38. Early Postoperative Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy (EPIC) offers a targeted approach to delivering chemotherapy directly to the peritoneal cavity, potentially enhancing therapeutic efficacy while minimizing systemic side effects. Early Postoperative Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy (EPIC) is often combined with cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC). Early Postoperative Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy (EPIC) provides a second opportunity to target and destroy cancer cells in the peritoneal cavity, especially those in areas that become inaccessible after the initial surgery. While some studies suggest potential survival benefits, especially for certain cancers, the use of EPIC is controversial due to increased risks of morbidity and longer hospital stays, leading many centers to use it less frequently today.

Early Postoperative Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy (EPIC) is initiated on the first postoperative day and then administered continuously for 5 to 7 days. During the procedure, a solution containing chemotherapy drugs is introduced into the peritoneal cavity, where it bathes the mesothelium for a duration between 4 and 24 hours. Subsequently, the solution is drained over an hour and then readministered 36, 37, 38. Before starting EPIC therapy, it is essential to ensure your postoperative status is stable, including a normal white blood cell count and tolerance to treatment. Depending on your condition, EPIC therapy may be delayed until the second postoperative day. A catheter is secured with sutures to facilitate drug delivery, and multiple closed suction drains are placed for drainage. The chemotherapy drugs employed in EPIC are typically cell-specific, in contrast to the cell cycle nonspecific drugs used in other intraperitoneal chemotherapy regimens such as HIPEC. Commonly used agents include 5-fluorouracil, taxanes, and leucovorin 39.

Pressurized Intraperitoneal Aerosol Chemotherapy (PIPAC)

Pressurized Intraperitoneal Aerosol Chemotherapy (PIPAC) is a newer method to treat peritoneal carcinomatosis. Pressurized Intraperitoneal Aerosol Chemotherapy (PIPAC) is a minimally invasive surgical technique that delivers low-dose chemotherapy as a pressurized aerosol directly into the abdominal cavity to treat peritoneal metastases 40. The pressure helps the chemotherapy drugs penetrate the tissue more deeply and evenly, potentially improving treatment effectiveness and reducing systemic side effects compared to traditional chemotherapy. This procedure, often performed via laparoscopy, is repeated every few weeks and can also help relieve symptoms like pain and swelling.

Pressurized Intraperitoneal Aerosol Chemotherapy (PIPAC) is typically considered for patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis that are not candidates for curative surgery (who may be deemed unresectable or unfit for surgery), such as those from ovarian, gastric, colorectal, or appendiceal cancers. Pressurized Intraperitoneal Aerosol Chemotherapy (PIPAC) is often recommended when other treatments have been ineffective or are not viable.

How pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC) works:

- Minimally invasive: It is performed using laparoscopy through a few small incisions.

- Pressurized aerosol: Chemotherapy drugs are delivered as a fine mist under high pressure, allowing for better distribution and deeper penetration into cancer tissue. During PIPAC, a special aerosolized mist of chemotherapy drug is put directly into the belly during a minimally invasive procedure. The chemotherapy drug is given as a fine aerosol under pressure, which helps it spread evenly throughout the abdomen.

- Procedure steps: The surgeon first takes tissue samples, then sprays the aerosolized chemotherapy for about 10 minutes, lets it sit for 30 minutes, and finally evacuates the gas before closing the incisions.

- Symptom relief: PIPAC can help ease symptoms such as abdominal pain and swelling, improving a patient’s quality of life.

- Repeated treatments: The procedure is typically repeated about every six weeks.

- Combined therapy: It is often used in conjunction with systemic chemotherapy.

Pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC) benefits and potential advantages:

- Improved drug delivery: The pressurized aerosol helps the chemotherapy spread more evenly throughout the abdominal cavity.

- Deeper tissue penetration: The pressure enhances drug absorption into the cancer tissue.

- Reduced systemic toxicity: Absorption into the bloodstream is limited, leading to potentially fewer systemic side effects like nausea, vomiting, and hair loss.

- Tissue analysis: Small tissue samples can be taken during the procedure, allowing doctors to study how the tumor responds to treatment.

Pressurized Intraperitoneal Aerosol Chemotherapy (PIPAC) is typically done when surgery isn’t possible or when surgery would be too risky or not helpful. PIPAC has also been found to have superior benefits of chemotherapy drug delivery to tumor tissue with a significant effect on tumor regression than conventional intraperitoneal chemotherapy or systemic chemotherapy 41.

Pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC) side effects:

- Some discomfort, minor abdominal pain, or mild nausea can occur after the procedure.

- More serious adverse events are uncommon, but can include abdominal pain, bleeding, or bowel obstruction.

Bidirectional/Neoadjuvant Intraperitoneal and Systemic Chemotherapy

The bidirectional/neoadjuvant intraperitoneal and systemic chemotherapy (BIPSC/NIPS) approach is a novel treatment strategy developed in Japan, primarily aimed at optimizing outcomes for patients with gastric cancer 42, 43, 44, 21. The bidirectional/neoadjuvant intraperitoneal and systemic chemotherapy (BIPSC/NIPS) procedure involves several sequential steps to address different aspects of the disease. Initially, patients undergo neoadjuvant intraperitoneal and systemic chemotherapy (NIPS) to reduce the tumor burden. This neoadjuvant chemotherapy is administered both systemically and directly into the peritoneal cavity, aiming to target cancer cells both within the stomach and any potential peritoneal spread. Following neoadjuvant intraperitoneal and systemic chemotherapy (NIPS), patients undergo cytoreductive surgery (CRS) to remove any remaining macroscopic tumor lesions surgically. This extensive surgical procedure aims to eliminate visible tumors and achieve complete cytoreduction. Subsequently, patients receive hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC), which involves delivering heated chemotherapy directly into the abdominal cavity to destroy any remaining cancer cells and prevent disease recurrence.

The final component of the BIPSC/NIPS approach is Early Postoperative Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy (EPIC). EPIC involves administering chemotherapy directly into the peritoneal cavity in the immediate postoperative period, aiming to target and eradicate residual microscopic peritoneal deposits. By combining systemic chemotherapy, intraperitoneal chemotherapy, CRS, HIPEC, and EPIC, the BIPSC/NIPS approach aims to manage gastric cancer (and potentially other peritoneal cancers) comprehensively, addressing both localized and peritoneal disease spread while minimizing the risk of recurrence and improving patient outcomes 45, 46.

Palliative care

When peritoneal carcinomatosis can’t be cured or treated with chemotherapy or surgery, the focus may turn to comfort and quality of life. Palliative care is a specialized medical care for people with serious illnesses, focusing on improving their quality of life by relieving pain and other symptoms, such as digestive issues, malnutrition and fluid buildup, called ascites. Palliative care’s goal is to improve the quality of life for people with serious illnesses and their families. Treatments may include fluid drainage, pain relief medicines and nutritional support. Palliative care can be provided at any stage of an illness, alongside curative treatments, and supports both the patient and their family. The care is delivered by an interdisciplinary team of doctors, nurses, social workers, and others, working with the patient’s other doctors.

Palliative care is not the same as hospice care, although it can include hospice services. Hospice is a specific type of palliative care for those with a terminal illness who are nearing the end of life.

It can be delivered in various settings, including hospitals, clinics, nursing homes, and at home.

What palliative care provides:

- Symptom relief: Eases pain, nausea, shortness of breath, fatigue, and other distressing symptoms.

- Emotional and spiritual support: Helps with stress, anxiety, depression, and spiritual concerns.

- Practical support: Assists with issues like employment, insurance, and making difficult decisions about future care.

- Care coordination: Works with the patient’s other healthcare providers to ensure the care plan aligns with the person’s goals and values.

- Support for families: Provides practical and emotional support for family members and caregivers.

Who can benefit from palliative care:

- Anyone living with a serious, chronic, or life-limiting illness, such as cancer, heart disease, lung disease, or dementia.

- Individuals at any age and at any stage of their illness, from diagnosis to end-of-life.

Peritoneal carcinomatosis prognosis

Peritoneal carcinomatosis is a serious and often late-stage condition with a challenging prognosis, whether originating in the peritoneum or metastasizing from elsewhere. Depending on how aggressive the cancer is, people with peritoneal carcinomatosis from more advanced cancers may live only 4 to 6 months on average with a median survival of around 6 months when treated with systemic chemotherapy alone. However, some people may live longer if they are healthy enough to have CRS-HIPEC. In some studies, CRS-HIPEC extended survival by more than three years. For people who can’t have surgery, newer treatments such as pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC) also may help them live longer. Factors such as the primary tumor’s location significantly influence survival rates, with pancreatic origin associated with the poorest prognosis (2.9 months), followed by gastric (6.5 months) and colorectal origin (6.9 months) 47. The presence of ascites and liver metastasis further negatively impacts survival outcomes.

People with primary peritoneal cancer (mesothelioma) typically presents as advanced stage 4 disease, with a survival rate ranging from 11 to 17 months. 14.

Primary peritoneal cancer

Primary peritoneal cancer is a relatively rare cancer that starts in the thin layer of tissue lining the inside of the abdomen called the peritoneum and develops most commonly in women 14, 48. Primary peritoneal cancer is very rare in men. Most people are over the age of 60 when they are diagnosed. Primary peritoneal cancer is a close relative of epithelial ovarian cancer, which is the most common type of malignancy that affects the ovaries. Primary peritoneal cancer cells are the same as the most common type of ovarian cancer cells. This is because the lining of the abdomen and the surface of the ovary come from the same tissue when you develop from embryos in the womb. So doctors treat primary peritoneal cancer in the same way as ovarian cancer. The cause of primary peritoneal cancer is unknown, but it is important for women to know that it is possible to have primary peritoneal cancer even if your ovaries have been removed.

The estimated incidence of primary peritoneal cancer in the United States is 6.78 cases per 1,000,000 individuals 49. American cancer research suggests that around 10 out of 100 (around 10%) of all women with ovarian, fallopian and peritoneal serous cancers have primary peritoneal cancer.

The abdominal cavity and the entire surface of all the organs in the abdomen are covered in a cellophane-like, glistening, moist sheet of tissue called the peritoneum. It not only protects the abdominal organs, it also supports and prevents them from sticking to each other and allows them to move smoothly within the abdomen. The cells of the peritoneal lining develop from the same type of cell that lines the surface of the ovary and fallopian tube for that matter. Certain cells in the peritoneum can undergo transformation into cancerous cells, and when this occurs, the result is primary peritoneal cancer. It can occur anywhere in the abdominal cavity and affect the surface of any organ contained within it. It differs from ovarian cancer because the ovaries in primary peritoneal cancer are usually only minimally affected with cancer.

The fallopian tubes are a pair of floppy tube-like structures that originate at the top (fundus) of the uterus where they communicate with the endometrial cavity and course away from the uterus, on either side, towards the ovaries where they “flop” over the ovaries with their finger-like (fimbriated) end. Cancers of the fallopian tube are also relatively rare and very closely related to cancers of the ovary and primary peritoneal cancer. They share many commonalities and emerging data is even suggesting that many of the previously felt to be ovarian cancers may indeed have been fallopian tube cancer.

Although the clinical presentation of fallopian tube cancer is very similar to ovarian cancer and primary peritoneal cancer, there are some differences. Cancers of the fallopian tube arise within the inside (lumen) of the fallopian tube and typically cause it to swell like a sausage. The involvement of the ovary is secondary, but it is usually so extensive that one cannot tell whether it began on the ovary and spread to the fallopian tube, or vice versa. Because of that, many fallopian tube cancers may have been classified as ovarian cancers. As the fallopian tube swells with cancer, it produces fluid, similar to ascites, that can “leak” back into the uterus and lead to a watery vaginal discharge, the classic presentation of fallopian tube cancer when associated with an adnexal mass.

The treatment you have depends on a number of things including:

- the size of your cancer

- where the cancer is in the abdomen, and if it has spread further away

- your general health

The treatment for primary peritoneal cancer is the same as for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer.

The aim of treatment for advanced cancer is usually to shrink the cancer and control it for as long as possible. You might have the following treatments.

Surgery

The aim of surgery is to remove as much of the cancer from the abdomen as possible before chemotherapy. This is called debulking surgery.

Chemotherapy tends to work better when there are only small tumors inside the abdomen. The surgery usually includes removing your womb, ovaries, fallopian tubes and the layer of fatty tissue called the omentum.

The surgeon will also remove any other cancer that they can see at the time of surgery. This could include part of the bowel if the cancer has spread there.

Sometimes primary peritoneal cancer can grow so that it blocks the bowel or the urinary system. You might need surgery to unblock these if this happens.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy uses anti cancer (cytotoxic) drugs to destroy cancer cells. These drugs work by disrupting the growth of cancer cells. The drugs circulate in the bloodstream around the body.

You may have chemotherapy:

- before surgery to reduce the size of the cancer

- after surgery when you have recovered

- on its own if you are unable to have surgery

The most common chemotherapy drugs used to treat primary peritoneal cancer are a combination of carboplatin and paclitaxel (Taxol).

Radiation therapy

Radiotherapy uses high energy x-rays to kill cancer cells. Radiotherapy isn’t often used for primary peritoneal cancers. But doctors may use it to shrink tumours and reduce symptoms.

Other treatments

You can have treatment to control symptoms, such as pain and fluid in the abdomen (ascites), even if you are unable to have chemotherapy.

Fluid can build up between the two layers of the peritoneum. It can be very uncomfortable and heavy.

Your doctor can drain the fluid off using a procedure called abdominal paracentesis or an ascitic tap. The diagram below shows this.

Primary peritoneal cancer causes

The causes of primary peritoneal cancer are unknown. Most cancers are caused by a number of different factors working together. Research suggests that a very small number of primary peritoneal cancers may be linked to the inherited faulty genes BRCA 1 and BRCA 2. These are the same genes that increase the risk of ovarian cancer and breast cancer.

Primary peritoneal cancer symptoms

Symptoms for primary peritoneal cancer can be very unclear and difficult to spot. Many of the symptoms are more likely to be caused by other medical conditions.

Unfortunately, because of the vague nature of the signs, primary peritoneal cancer and fallopian tube cancer are usually diagnosed in advanced stages of disease, when achieving a cure is difficult.

The typical symptoms of both are more commonly gastrointestinal rather than gynecologic in nature, and include:

- Abdominal bloating

- Changes in bowel habits

- Early feeling of fullness after eating

- Bloating and when severe, nausea and vomiting may result

- Constipation or diarrhea

- Feeling or being sick

- Feeling bloated

- Loss of appetite

Occasionally, patients can present with a blockage of the intestines related to tumor on or next to the bowels. Vaginal bleeding is infrequently seen in patients with primary peritoneal cancer, but may be a little more common in patients with fallopian tube cancer.

Primary peritoneal cancer diagnosis

Both primary peritoneal cancer and fallopian tube cancer are usually diagnosed when a woman sees her doctor complaining of abdominal swelling and bloating. As described above, the symptoms of either cancer are more commonly gastrointestinal than gynecologic in nature. These symptoms are related to the accumulation of fluid, also known as ascites, that commonly occurs with either cancer. Gastrointestinal symptoms also occur because seedlings of tumor often line the peritoneal surface (the outer lining) of the intestines, a process called carcinomatosis. The omentum, an apron of fatty tissue that hangs down from the colon and stomach, often contains bulky tumor, described as omental caking. Although omental cakes can be detected on a physical exam, they frequently are subtle and difficult to detect. When a woman is found to have fluid in the abdomen (ascites), the usual first step toward a diagnosis is a CT scan. This is a special type of x-ray test that allows doctors to assess the entire abdomen and pelvis. Omental caking and ascites, as well as other tumor growths, are commonly seen, and point toward the diagnosis of primary peritoneal cancer, fallopian tube cancer or ovarian cancer. Other cancers can cause these findings, thus, further tests are needed and are usually focused around ruling out other more common cancers, such as colon and breast cancer.

Frequently, the evaluation of ascites begins with a procedure known as a paracentesis, whereby fluid is removed from the abdomen using a needle. The fluid is examined under the microscope, looking for the presence of cancerous cells. Unfortunately, this procedure is not without risks as the process of performing a paracentesis can actually “seed” the abdominal wall with cancer cells. Therefore, it is important to seek the advice of a gynecologic oncologist when considering this procedure as it may not be necessary given that most patients with these findings will undergo surgery regardless of the results. However, it may be helpful in the patient who is either not a surgical candidate, or in one suspected of having ascites for reasons other than cancer, such as liver or heart disease. Sometimes fluid is even drawn off because of patient discomfort until surgery or chemotherapy can be scheduled.

There are several blood tests that are frequently performed when either primary peritoneal cancer or fallopian tube cancer is suspected. The most common of which is the CA 125 blood test. CA 125 is a chemical that is made by tumor cells and is usually elevated in patients with primary peritoneal cancer and fallopian tube cancer. Unfortunately, it can also be elevated in a variety of benign conditions, as well as other cancers, and thus an elevated CA 125 blood test does not mean the patient has a cancer. More recently a newer blood test, HE4, can also be used as it is less likely elevated than CA 125 in benign conditions. You can read more about CA 125 with our brochure, CA 125 Levels: Your Guide.

The actual diagnosis of primary peritoneal cancer or fallopian tube cancer is often not completely certain until a woman undergoes surgery. This is because the clinical presentation of either disease is so similar to that of epithelial ovarian cancer. primary peritoneal cancer, fallopian tube cancer and ovarian cancer appear identical under the microscope. It is the pattern of tumor distribution and organ involvement in the abdominal cavity that indicates the origin of the primary cancer. Patients with fallopian tube cancer usually have gross involvement of the fallopian tubes with lesser involvement of the ovaries. Patients with primary peritoneal cancer are usually found to have normal ovaries, or only superficial involvement of the ovaries, at the time of pre-surgical imaging tests or at time of surgery. However, the diagnosis can occasionally remain uncertain even following surgery.

Surgical staging

Surgical staging of cancers is performed in order to fully assess the extent of disease. This allows for decisions to be made regarding additional therapy, which is usually in the form of chemotherapy. Surgical staging generally involves removal of all visible disease, as well as removal of the ovaries, fallopian tubes and uterus. It can also include removal of the omentum, lymph nodes and other organs depending on the surgical findings.

While there is no formal agreed-upon staging system for primary peritoneal cancer, because it is so similar to ovarian cancer with respect to treatment, tumor state is typically assigned using guidelines established for ovarian cancer.

Stages 1 through 4 describe how far the tumor has spread. Nearly all patients diagnosed will have stage 3 or higher because warning signs are typically few until the cancer is widespread. Patients with primary peritoneal cancer or fallopian tube cancer may have fluid around the lungs, known as a pleural effusion. If an effusion is present, some fluid may be removed in order to look for tumor cells. If tumor cells are found in this fluid, the patient has stage 4 disease.

Ovarian cancer stages

The 2 systems used for staging ovarian cancer, the FIGO (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics) system and the AJCC (American Joint Committee on Cancer) TNM staging system are basically the same.

They both use 3 factors to stage (classify) this cancer :

- The extent (size) of the tumor (T): Has the cancer spread outside the ovary or fallopian tube? Has the cancer reached nearby pelvic organs like the uterus or bladder?

- The spread to nearby lymph nodes (N): Has the cancer spread to the lymph nodes in the pelvis or around the aorta (the main artery that runs from the heart down along the back of the abdomen and pelvis)? Also called para-aortic lymph nodes.

- The spread (metastasis) to distant sites (M): Has the cancer spread to fluid around the lungs (malignant pleural effusion) or to distant organs such as the liver or bones?

Numbers or letters after T, N, and M provide more details about each of these factors. Higher numbers mean the cancer is more advanced. Once a person’s T, N, and M categories have been determined, this information is combined in a process called stage grouping to assign an overall stage.

The staging system in the table below uses the pathologic stage (also called the surgical stage). It is determined by examining tissue removed during an operation. This is also known as surgical staging. Sometimes, if surgery is not possible right away, the cancer will be given a clinical stage instead. This is based on the results of a physical exam, biopsy, and imaging tests done before surgery.

The system described below is the most recent American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) system effective January 2018. It is the staging system for ovarian cancer, fallopian tube cancer, and primary peritoneal cancer.

Cancer staging can be complex, so ask your doctor to explain it to you in a way you understand.

Table 1. Ovarian cancer stages

| AJCC Stage | Stage grouping | FIGO Stage | Stage description* |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | T1 N0 M0 | I | The cancer is only in the ovary (or ovaries) or fallopian tube(s) (T1). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| IA | T1a N0 M0 | IA | The cancer is in one ovary, and the tumor is confined to the inside of the ovary; or the cancer is in one fallopian tube, and is only inside the fallopian tube. There is no cancer on the outer surfaces of the ovary or fallopian tube. No cancer cells are found in the fluid (ascites) or washings from the abdomen and pelvis (T1a). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| IB | T1b N0 M0 | IB | The cancer is in both ovaries or fallopian tubes but not on their outer surfaces. No cancer cells are found in the fluid (ascites) or washings from the abdomen and pelvis (T1b). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| IC | T1c N0 M0 | IC | The cancer is in one or both ovaries or fallopian tubes and any of the following are present:

It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| II

| T2 N0 M0 | II | The cancer is in one or both ovaries or fallopian tubes and has spread to other organs (such as the uterus, bladder, the sigmoid colon, or the rectum) within the pelvis or there is primary peritoneal cancer (T2). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| IIA | T2a N0 M0 | IIA | The cancer has spread to or has invaded (grown into) the uterus or the fallopian tubes, or the ovaries. (T2a). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| IIB | T2b N0 M0 | IIB | The cancer is on the outer surface of or has grown into other nearby pelvic organs such as the bladder, the sigmoid colon, or the rectum (T2b). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| IIIA1 | T1 or T2 N1 M0 | IIIA1 | The cancer is in one or both ovaries or fallopian tubes, or there is primary peritoneal cancer (T1) and it may have spread or grown into nearby organs in the pelvis (T2). It has spread to the retroperitoneal (pelvic and/or para-aortic) lymph nodes only. It has not spread to distant sites (M0). |

| IIIA2 | T3a N0 or N1 M0 | IIIA2 | The cancer is in one or both ovaries or fallopian tubes, or there is primary peritoneal cancer and it has spread or grown into organs outside the pelvis. During surgery, no cancer is visible in the abdomen (outside of the pelvis) to the naked eye, but tiny deposits of cancer are found in the lining of the abdomen when it is examined in the lab (T3a). The cancer might or might not have spread to retroperitoneal lymph nodes (N0 or N1), but it has not spread to distant sites (M0). |

| IIIB | T3b N0 or N1 M0 | IIIB | There is cancer in one or both ovaries or fallopian tubes, or there is primary peritoneal cancer and it has spread or grown into organs outside the pelvis. The deposits of cancer are large enough for the surgeon to see, but are no bigger than 2 cm (about 3/4 inch) across. (T3b). It may or may not have spread to the retroperitoneal lymph nodes (N0 or N1), but it has not spread to the inside of the liver or spleen or to distant sites (M0). |

| IIIC | T3c N0 or N1 M0 | IIIC | The cancer is in one or both ovaries or fallopian tubes, or there is primary peritoneal cancer and it has spread or grown into organs outside the pelvis. The deposits of cancer are larger than 2 cm (about 3/4 inch) across and may be on the outside (the capsule) of the liver or spleen (T3c). It may or may not have spread to the retroperitoneal lymph nodes (N0 or N1), but it has not spread to the inside of the liver or spleen or to distant sites (M0). |

| IVA | Any T Any N M1a | IVA | Cancer cells are found in the fluid around the lungs (called a malignant pleural effusion) with no other areas of cancer spread such as the liver, spleen, intestine, or lymph nodes outside the abdomen (M1a). |

| IVB | Any T Any N M1b | IVB | The cancer has spread to the inside of the spleen or liver, to lymph nodes other than the retroperitoneal lymph nodes, and/or to other organs or tissues outside the peritoneal cavity such as the lungs and bones (M1b). |

Footnotes:

* The following additional categories are not described in the table above:

- TX: Main tumor cannot be assessed due to lack of information

- T0: No evidence of a primary tumor.

- NX: Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed due to lack of information.

Primary peritoneal cancer treatment

Both primary peritoneal cancer and fallopian tube cancer are treated in the same way as ovarian cancer is treated. They are most often treated with surgery and chemotherapy—only rarely is radiation therapy used. Your specific treatment plan will depend on several factors, including:

- Stage and grade of the cancer

- Size and location of the cancer

- Your age and general health

All treatments for either cancer have side effects. Most side effects can be managed or avoided. Treatments may affect unexpected parts of your life, including your function at work, home, intimate relationships and deeply personal thoughts and feelings.

Before beginning treatment, it is important to learn about the possible side effects and talk with your treatment team members about your feelings or concerns. They can prepare you for what to expect and tell you which side effects should be reported to them immediately. They can also help you find ways to manage the side effects you experience.

Surgery

Surgery is usually the first step in treating primary peritoneal cancer or fallopian tube cancer and it should be performed by a gynecologic oncologist. The goal of the surgery is the removal of all visible disease because this approach has been shown to improve survival. This process is known as “debulking” surgery. When all visible disease is removed, or if only small tumor implants (less than 1 cm in diameter) remain, the patient is considered optimally debulked. Occasionally, the location of tumor within the abdomen or the condition of the patient does not allow for optimal debulking surgery to be performed. In this situation, chemotherapy may be given first and the patient might have surgery at a later time. Most surgery is performed using a procedure called a laparotomy during which the surgeon makes a long cut in the wall of the abdomen, although they are also commonly found at laparoscopy. If either primary peritoneal cancer or fallopian tube cancer is found, the gynecologic oncologist performs the following procedures:

- Salpingo-ooophorectomy: both ovaries and fallopian tubes are removed.

- Hysterectomy: the uterus is removed usually with the attached cervix.

- Omentectomy: the omentum, a fatty pad of tissue that covers the intestines, is removed.

Occasionally, some of the nearby lymph nodes will be removed. Depending on the surgical findings, more extensive surgery, including removal of portions of the small or large intestine and removal of tumor from the liver, diaphragm and pelvis, may be performed. Removal of as much tumor as possible is one of the most important factors affecting cure rates.

Side effects of surgery

Some discomfort is common after surgery. It often can be controlled with medicine. Tell your treatment team if you are experiencing pain. Other possible side effects are:

- Nausea and vomiting

- Infection, fever

- Wound problem

- Fullness due to fluid in the abdomen

- Shortness of breath due to fluid around the lungs

- Anemia

- Swelling caused by lymphedema, usually in the legs or arms

- Blood clots

- Difficulty urinating or constipation

- Talk with your doctor if you are concerned about any of the problems listed.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the use of drugs to kill cancer cells. It can be given intravenously (injected into a vein) or, more recently, intraperitoneal administration has become popular because it is associated with a longer survival in patients with a very similar cancer, ovarian cancer. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy involves the administration of medicines directly into the abdomen through a catheter which is placed under the skin at the time of initial surgery, or shortly thereafter. Unfortunately, it has more immediate side effects than intravenous chemotherapy and therefore some patients prefer the more traditional intravenous administration. Intraperitoneal treatment is only given if optimal debulking surgery has been achieved. Either treatment may be administered in the doctor’s office, outpatient treatment areas of the hospital or, occasionally, as an inpatient.

Traditionally, intravenous chemotherapy is given every three weeks as an outpatient. Each treatment of chemotherapy is known as a cycle and initial treatment usually consists of six cycles. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy is also given on an every three-week schedule for six cycles. Each cycle is a little more involved as the patient might receive treatments on several days of the 21 day cycle compared to receiving treatments on only day 1 of the cycle if given intravenously.

The most commonly used chemotherapy medicines for primary peritoneal cancer are the same as those used for ovarian cancer. These include one of the platinum-based medicines, Cisplatin or Carboplatin, as well as Taxane (Paclitaxel or Taxotere) in combination.

Side effects of chemotherapy

Each person responds to chemotherapy differently. Some people may have very few side effects while others experience several. Most side effects are temporary. They include:

- Nausea

- Loss of appetite

- Mouth sores

- Increased chance of infection

- Bleeding or bruising easily

- Vomiting

- Hair loss

- Fatigue

- Constipation

- Diarrhea

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy may be utilized for treatment of isolated small areas of disease that has returned after initial therapy. It is rarely used as a first therapy for either primary peritoneal cancer or fallopian tube cancer.

Other treatments

You can have treatment to control symptoms, such as pain and fluid in the abdomen (ascites), even if you are unable to have chemotherapy.

Fluid can build up between the two layers of the peritoneum. It can be very uncomfortable and heavy.

Your doctor can drain the fluid off using a procedure called abdominal paracentesis or an ascitic tap. The diagram below shows this.

Follow up after treatment

After initial treatment is completed, patients with either cancer are followed closely with visits every two to four months for the first three years and then every six months for another two years or so and ultimately yearly. At each visit they have a physical exam, including a pelvic exam, CA 125 testing, and, depending on the patient and her situation, imaging tests, such as CT scans, X-rays, MRIs or PET scans, may be performed. Unless patients are diagnosed early these cancers have a tendency to recur with time. Hence, patients often require more than one round of chemotherapy and may also need additional surgical procedures.

Recurrent disease