Contents

- Acne

- Types of acne

- What causes acne?

- Acne prevention

- Symptoms of acne

- Acne complications

- How is acne diagnosed?

- Acne vulgaris differential diagnosis

- Acne treatment

- Table 1. Nonantibiotic topical agents for the treatment of acne vulgaris

- Table 2. Topical antibiotics for the treatment of acne vulgaris

- Table 3. Topical retinoids for the treatment of acne vulgaris

- Table 4. Oral antibiotics for the treatment of moderate to severe inflammatory acne vulgaris

- Benzoyl peroxide

- Topical antibiotics

- Retinoids

- Isotretinoin

- Azelaic acid

- Dapsone

- Other topical agents

- Oral antibiotics

- Hormonal agents

- Antiandrogens

- Corticosteroids

- Physical modalities

- Complementary and alternative medicines

- Best acne treatment

- Acne scar treatment

- Acne in pregnancy

- Acne prognosis

- Living with acne

Acne

Acne also known as pimple or acne vulgaris, is a very common chronic inflammatory skin condition affecting the hair follicle and sebaceous (oil) gland in which there is expansion and blockage of the hair follicle and inflammation, identified by the presence of comedones (blackheads and whiteheads) and pus-filled spots (pustules). Doctors refer to enlarged or plugged hair follicles as comedones. Acne affects males and females of all races and ethnicities. Acne usually starts during puberty, with 85% of 16 to 18 year-olds affected, but may persist into the 30s and 40s 1. About 4 out of every 5 people experience acne outbreaks between the ages of 11 and 30. However, acne may sometimes occur in children and adults of all ages. Occasionally, young children will develop blackheads and/or pustules (pus-filled spots) on the cheeks or nose. Acne can also develop for the first time in people in their late twenties and beyond. Acne ranges from a few spots on the face, neck, back and chest, which most teenagers will have at some time, to a more severe problem that may cause scarring, dyspigmentation (an abnormality in the formation or distribution of pigmentation in the skin), depression, anxiety and low self-esteem 2. For most (over 90 percent), acne vulgaris tends to go away by the early to mid twenties (before 30 years of age), but it can go on for longer with an unpredictable course or persistence well into the 5th and 6th decades 3.

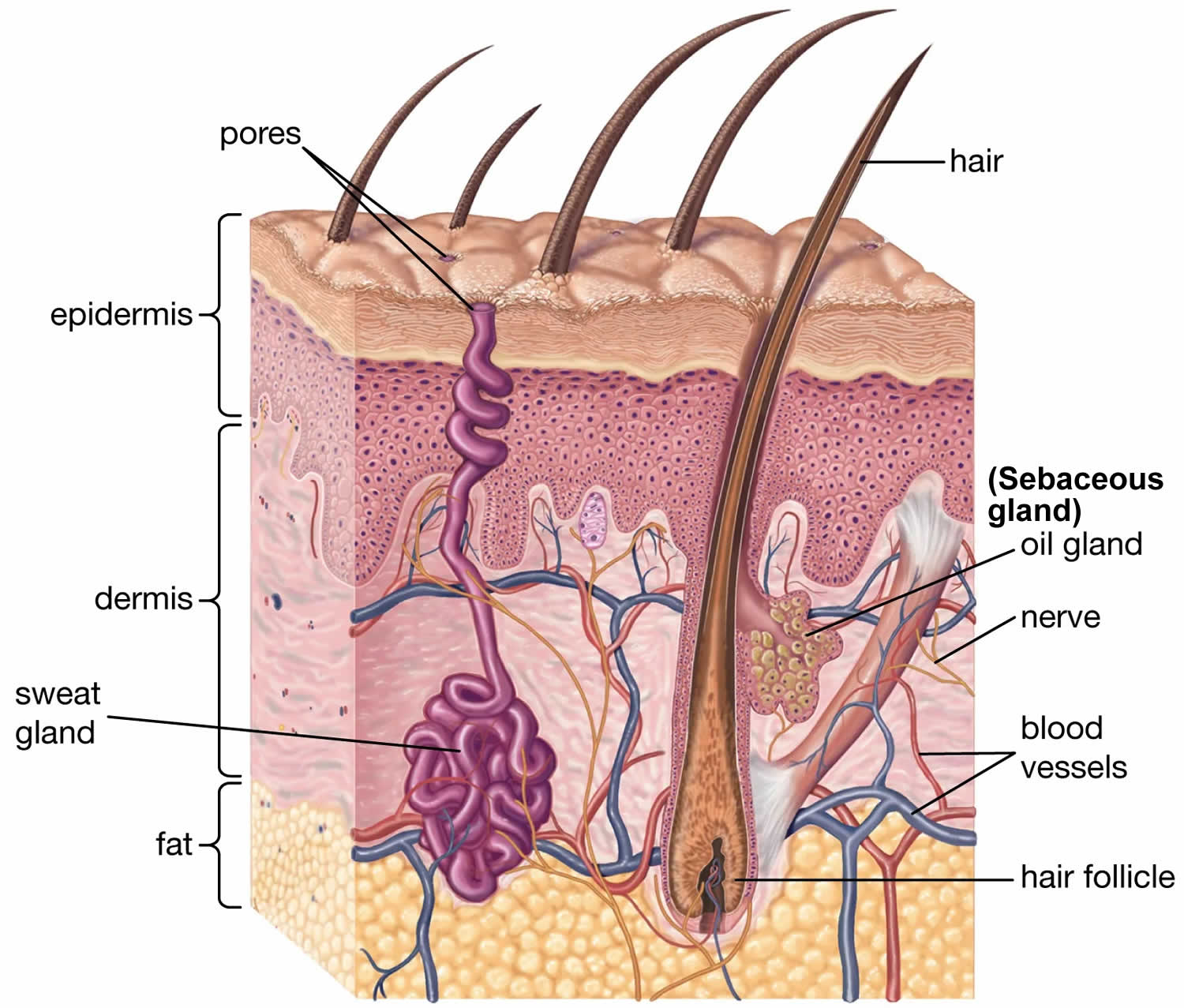

Acne is caused by debris that block the hair follicles in your skin (Figure 1). The debris is made up of dead skin and oil. This blockage allows bacteria to grow in the hair follicles. Sebaceous glands (oil glands) are tiny glands found near the surface of your skin. The oil glands are attached to hair follicles, which are small holes in your skin that an individual hair grows out of. Sebaceous glands lubricate the hair and the skin to stop it drying out. They do this by producing an oily substance called sebum. In acne, the sebaceous glands begin to produce too much sebum. The excess sebum mixes with dead skin cells and both substances form a plug in the follicle. If the plugged follicle is close to the surface of the skin, it bulges outwards, creating a whitehead. Alternatively, the plugged follicle can be open to the skin, creating a blackhead. Normally harmless bacteria that live on the skin can then contaminate and infect the plugged follicles, causing papules, pustules, nodules or cysts.

Family history also contributes to acne. If your parents had bad acne, you may have it too. Your immune system plays a role too. Some people are extra sensitive to the bacteria that get trapped in their hair follicles.

Types of acne include:

- Whiteheads: The tiny hair follicles in your skin becomes blocked with oil and dead skin that stay beneath the skin and produce a white bump. A “whitehead” forms at the tip of each pimple.

- Blackheads: Plugged hair follicles that reach the surface of the skin and open up. They look black on the skin surface because the air discolors the sebum, not because they are dirty.

- Papules: Inflamed lesions that usually appear as small, pink bumps on the skin and can be tender to the touch.

- Pustules or pimples: Papules topped by white or yellow pus-filled lesions that may be red at the base.

- Nodules: These are more serious acne lesions. Large, painful solid lesions that are lodged deep within the skin and can cause scarring.

- Severe nodular acne sometimes called cystic acne: Deep, painful, pus-filled lesions. Cysts form deep in the skin around the hair follicle and can cause scarring.

Acne is characterized by:

- Open and closed uninflamed comedones (blackheads and whiteheads)

- Inflamed papules (small raised, tender bumps on the skin) and pustules (small, inflamed, pus-filled, blister-like sores (lesions) on the skin surface)

- In severe acne, nodules and pseudocysts

- Post-inflammatory reddish or pigmented macules and scars

- Adverse social and psychological effects. Having acne can cause embarrassment and anxiety.

Acne lesions typically confined to the face, but it may involve the neck, chest, and upper back 4. The lesions may be noninflammatory closed comedones (i.e., papules formed by the accumulation of sebum/keratin within the hair follicle; also called whiteheads); open comedones (i.e., distension of the hair follicle with keratin leads to opening of the follicle, oxidation of lipids, and deposition of melanin; also called blackheads); or inflammatory papules, nodules, pustules, and cysts 4. Inflammatory lesions result from hair follicle rupture triggering an inflammatory response. Based on the extent and types of lesions, acne severity may be classified as mild, moderate, or severe. However, there is currently no universally accepted grading system for acne 1.

Acne severity is classified as mild, moderate, or severe.

- Mild acne: total lesion count <30 or <20 comedones or <15 inflammatory lesions

- Moderate acne: total lesion count 30–125 or 20–100 comedones or 15–50 inflammatory lesions

- Severe acne: total lesion count >125 or >5 pseudocysts or total comedones count >100 or total inflammatory lesions >50

Some dermatologists assess the severity of a patient’s acne more precisely by using a grading scale. The inflammatory lesions are compared with a set of standard photographs to determine the grade, which may be 1 (very mild) to 12 (exceptionally severe) for example. In clinical trials evaluating acne treatment, the numbers of non-inflamed and inflamed lesions are carefully counted at regular intervals. It is remarkably difficult to count consistently.

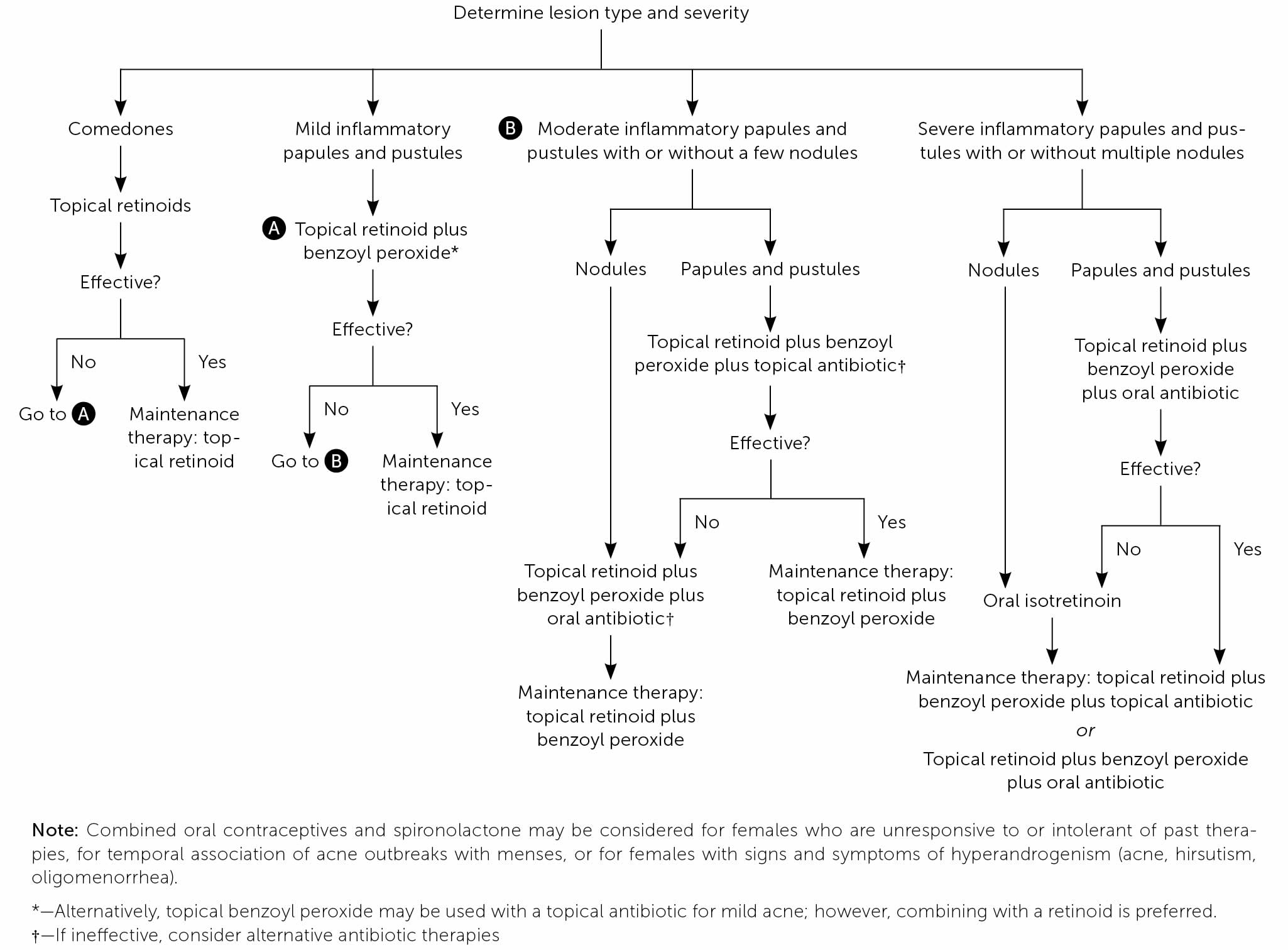

Goals of therapy in patients with acne vulgaris include reduction in comedonal and inflammatory lesions, improvement of psychosocial symptoms, and avoidance of scarring 5. Acne treatment selection is based on disease severity, patient preference, and tolerability. Topical retinoids are indicated for acne of any severity and for maintenance therapy. Systemic and topical antibiotics should be used only in combination with benzoyl peroxide and retinoids and for a maximum of 12 weeks. Therapeutic interventions for acne should have a minimum duration of eight weeks to assess effectiveness, unless the patient has an allergy or experiences intolerable adverse effects. There is limited evidence for physical modalities (e.g., laser therapy, light therapy, chemical peels) and complementary therapies (e.g., purified bee venom, low-glycemic-load diet, tea tree oil); therefore, further study is required. If the patient shows inadequate improvement after sequential interventions, referral to a dermatologist is recommended 5.

Isotretinoin is used for severe, recalcitrant acne. Because of the risk of teratogenicity, patients, pharmacists, and prescribers must register with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) mandated risk management program, iPledge, before implementing isotretinoin therapy.

Acne can be treated with over-the-counter (OTC) and prescription medicines. Your doctor will determine which is best for you.

OTC acne treatments include:

- Benzoyl peroxide and salicylic acid. This is the most common treatment. It comes in the form of a lotion, gel, soap, or cleansing pad. Benzoyl peroxide kills the bacteria and may decrease the production of sebum. Salicylic acid helps break down blackheads and whiteheads and also helps reduce the shedding of cells lining the hair follicles. It may take up to 8 weeks to see any improvement. Side effects include additional skin irritation, burning, and redness.

- Resorcinol can help break down blackheads and whiteheads.

- Sulfur helps break down blackheads and whiteheads.

Acne prescription medicines include:

- Retinoid creams or gels. These are applied to the pimples and can help treat lesions and reduce inflammation. They can also help prevent the formation of acne and help with scarring. Pregnant women should not use certain retinoid products. They can cause birth defects. Tell your doctor if you are pregnant. Sun exposure can irritate acne treated with retinoid cream.

- Antibiotics. Certain types of antibiotics can be used with other acne treatments. Doctors usually prescribe antibiotics with other topical therapies and usually for moderate to severe acne, such as severe nodular acne (also called cystic acne).

- Isotretinoin. This is a strong medicine available under certain brand names. Treatment with isotretinoin can lead to long-term remission in many patients. It can cause serious side effects. Talk to your doctor about the side effects.

- Birth control pills. These are sometimes effective for women diagnosed with acne.

- Hormone therapy, used primarily in women, helps stop the effects of androgens on the sebaceous gland.

- Corticosteroids, which help lower inflammation in severe acne, including severe nodular acne. Your doctor may recommend injecting the medication directly into affected areas of your skin.

Additional treatments are available in your doctor’s office. These include skin peels, skin ablation, and laser or light treatments. These treatments may reduce scarring caused by acne. Small injections of steroid medicines can help treat large acne cysts. Finally, certain lifestyle changes may help. This includes a healthy diet and regular exercise.

Figure 1. Skin structures

Footnotes: Skin is the largest organ of the body. It consists of three layers of tissues: the epidermis, the dermis and the subcutaneous layer. The epidermis is the paper-thin outer layer of the skin. The outer layer of the epidermis consists of dead cells that are always flaking or washing off. These are replaced by new cells manufactured in the lower portion of the epidermis, which move upward to the outside of the skin. As they do so, the cells harden and die. This cycle of cell production and replacement takes about 28 days. The epidermis also contains melanocytes, the cells that contain melanin — the pigment that gives skin its color. Skin color is determined by the amount of melanin in these cells, not cell number. The more melanin, the darker the skin. The dermis, the middle layer of the skin, contains blood vessels, nerves, hair follicles, sweat glands and oil glands. It makes up about 90 percent of the skin’s thickness and is made up of collagen and elastic fibers that give the skin strength and elasticity. The subcutaneous layer, the deepest layer of skin, is mostly composed of fatty tissue. It also contains blood vessels and nerves. The fat insulates the body from extreme heat and cold and provides a cushion to protect the body from injuries.

Figure 2. Acne vulgaris (pimple)

Footnote: Inflammatory acne with pustules and scarring.

Figure 3. Mild acne

Footnote: Mild acne with closed comedones and pustules.

Figure 4. Moderate inflammatory acne

Footnote: Moderate inflammatory acne lesions with comedones, several papules and pustules, and few nodules.

Figure 5. Severe inflammatory acne

Footnote: Severe inflammatory acne lesions with comedones, several papules and pustules, multiple nodules, and scarring.

If you have mild acne, speak to a pharmacist about medicines to treat it.

If these do not control your acne or it’s making you feel very unhappy, see a doctor.

You should see a doctor if you have moderate or severe acne or you develop nodules or cysts, as they need to be treated properly to avoid scarring.

Try to resist the temptation to pick or squeeze the spots, as this can lead to permanent scarring.

Treatments can take up to 3 months to work, so do not expect results overnight. Once they do start to work, the results are usually good.

Is acne is contagious or infectious?

No. You cannot pass acne on to other people. Acne is caused by debris that block the hair follicles in your skin. The debris is made up of dead skin and oil. This blockage allows bacteria to grow in the hair follicles.

Does poor hygiene cause acne?

It is a myth that people get acne because they don’t wash enough. Too much washing or scrubbing the skin harshly can make acne worse. And washing away surface oils doesn’t do much to prevent or cure acne, because it forms under the skin. The best way to clean the face is to gently wash it twice a day with a mild soap or cleanser. Be careful to remove make-up without harsh scrubbing.

Can stress cause acne?

Stress doesn’t cause acne, but stress can make acne worse but data to support this view is limited. Stress may manifest itself as acne excoriee, where patients, usually females, habitually scratch the spots the moment they appear. Acne may also be a side effect of some medicines used to treat stress or depression. And in some cases, the social and emotional impact of acne lesions causes stress. Talk with your doctor if you have concerns.

Can sunbathing, sunbeds and sunlamps help improve my acne?

There’s no conclusive evidence that prolonged exposure to sunlight or using sunbeds or sunlamps can improve acne. Many medicines used to treat acne can make your skin more sensitive to light, so exposure could cause painful damage to your skin, and also increase your risk of skin cancer.

Can eating chocolate or greasy foods cause acne?

While many patients feel that eating chocolate or greasy foods causes acne, experts have not found a link between the eating chocolate or greasy foods and acne, but the evidence for a link between diet and acne indicates that acne may be related to a high glycemic index diet and limited data indicate that some dairy, especially skim milk, can worsen acne. There is insufficient evidence to endorse recommendations related to antioxidants, probiotics, and fish oil. It’s important to eat a healthy diet for good health.

Some people with acne have reported improvement in their skin when they follow a low-glycaemic index diet, which can be achieved by:

- Increasing the consumption of whole grains, fresh fruits and vegetables, fish, olive oil, garlic

- Decreasing the consumption of high-glycaemic index foods such as sugar, biscuits, cakes, ice creams and bottled drinks

How does acne affect women?

Most young women and men will have at least a few pimples over the course of their lives. But acne seems to affect men and women in different ways. Young men are more likely to have a more serious form of acne. Acne in young women tends to be more random and linked to hormone changes, such as the menstrual cycle. About 70% of females will notice an aggravation of the acne just before or in the first few days of the period. As women get older, acne often gets better. But some women have acne for many years. Some women even get acne for the first time at age 30 or 40.

For many women, acne can be an upsetting illness. Women may have feelings of depression, poor body image, or low self-esteem. But you don’t have to wait to outgrow acne or to let it run its course. Today, almost every case of acne can be resolved. Acne also can, sometimes, be prevented. Talk with your doctor or dermatologist (a doctor who specializes in treating skin problems) about how you can help prevent acne and if treatment would help you.

What triggers acne in women?

Many things can trigger acne in women:

- Hormone changes during puberty. During puberty, girls have an increase in male sex hormones called androgens. This increase causes the glands to get larger and make more sebum.

- Hormone changes as an adult. The menstrual cycle is one of the most common acne triggers. Acne lesions tend to form a few days before the cycle begins and go away after the cycle is completed. Other hormone changes, such as pregnancy and menopause, improve acne in some women. But some women have worse acne during these times. Stopping use of birth control pills can play a role as well.

- Medicines. Certain medicines, such as those used to treat epilepsy and types of depression.

- Make-up.

- Pressure or friction on the skin. Friction caused by bike helmets or backpacks can make acne worse.

- Family history. If other people in your family have acne, there is a greater chance you will have it.

Can birth control pills help treat acne?

For women who break out mainly around their menstrual cycle, some birth control pills can help. Research shows that these pills can clear acne by slowing down overactive oil glands in the skin. Sometimes, birth control pills are used along with a drug called spironolactone to treat acne in adult females. This medication lowers levels of the hormone androgen in the body. Androgen stimulates the skin’s oil glands. Side effects of this drug include irregular menstruation, breast tenderness, headache and fatigue. Spironolactone is not appropriate therapy for all patients.

Types of acne

Acne causes several types of lesions, or pimples. Types of acne include:

- Acne vulgaris (common acne or pimples)

- Nodulocystic acne

- Acne excorieé

- Acne fulminans

- Acne in children

- Acne in pregnancy

- Acne due to medicines

- Adult acne

- Acne scarring

- Chloracne

- Comedonal acne

- Follicular occlusion syndrome

- Infantile acne

Adult acne

Acne in adults is also called postadolescent acne. Adult acne can be persistent, with onset during teenaged years or late onset beginning after the age of 25 years. Adult acne affects up to 15% of women, but is usually reported to be less common in men.

Adult acne can be predominantly inflammatory, with papules and pustules, or predominantly comedonal, often with many large closed comedones (whiteheads). Deep inflammatory lesions and macrocomedones may result in scarring.

Adult acne usually presents as acne vulgaris (common acne). But adult acne often has the following characteristics 6:

- Acne is very persistent in some people and may continue into the 30s and 40s.

- Adult acne tends to be mild to moderate in severity.

- Affected women often complain of enlarged pores.

- Some reports have suggested it is more common in people with olive skin (skin phototype IV).

- Inflammatory lesions are common on the jawline and neck but may be seen anywhere on face, neck, chest or back.

- Premenstrual flares are common.

- Macrocomedones (large whiteheads) are more common than in younger individuals. They are mostly found on chin, cheeks and forehead.

- Environmental factors have been associated with comedonal acne, particularly oily face creams and smoking.

- Dietary factors, particularly refined carbohydrates (sugars), are blamed for increasing prevalence of acne.

- Onset of inflammatory acne is often attributed to stress.

As in younger subjects, hormonal factors may be important including pregnancy, polycystic ovarian disease and medicines (including supplements) with male hormone activity.

Adult acne treatment is no different from that in younger individuals. However, because of the persistence of the disorder, more aggressive treatments may be recommended for relatively mild symptoms. Many adults consider acne abnormal at their age and demand effective treatment.

Environmental factors should be evaluated, and patients with acne should be encouraged to minimise their intake of high glycaemic index foods. Make-up should be non-occlusive.

Mild acne is treated with topical anti-acne medications. This is suppressive, not curative, and needs to be continued to maintain effects. Some people find blue light treatment has moderate efficacy at reducing the number of inflammatory lesions.

More severe acne may also be treated with anti-inflammatory antibiotics such as tetracyclines. Antiandrogens such as certain oral contraceptives and spironolactone are also widely used as a treatment of persistent acne in women.

Oral isotretinoin can be very effective for adult acne. It is well tolerated in low doses and may result in suppression of the acne for several years or long term. However, it has important side effects and risks. It must not be taken in pregnancy as it may cause birth defects.

Pregnancy acne

During pregnancy, the severity of acne can improve or get worse. It is common for acne to get a bit worse in early pregnancy and for it to improve as pregnancy progresses 7. This may relate to the increased levels of estrogen present in pregnancy. A few women have severe flares of acne throughout pregnancy.

It is preferable to avoid drugs in pregnancy in case they have an effect on the fetus.

The absence of safety data can make it difficult to advise on treatment of acne in pregnancy. Most experts agree that topical treatments that can be used safely in pregnancy include 7:

- Benzoyl peroxide

- Azelaic acid

- Fruit acids such as glycolic acid

- Low-concentration salicylic acid preparations

Topical antibiotics and oral erythromycin may be prescribed if the acne is severe. Other antibiotics that may be prescribed are penicillins and cephalosporins.

Light and laser therapies for acne are also safe.

The following drugs MUST BE AVOIDED in pregnancy or if pregnancy is being contemplated.

DO NOT use topical preparations containing:

- Topical retinoids (tretinoin, isotretinoin and adapalene)

- High concentration salicylic acid

DO NOT take the following oral medicines:

- Tetracyclines in later pregnancy, eg doxycycline, minocycline, lymecycline — these may discolour the teeth of the baby

- Other oral antibiotics such as trimethoprim + sulphamethoxazole or fluoroquinolones

- Isotretinoin — a teratogen if taken during early or mid-pregnancy, causing fetal loss (miscarriage) or severe birth deformities

Acne in children

Acne in children or prepubertal acne has been classified into the following age groups by a panel convened by the American Acne and Rosacea Society 8:

- Neonatal acne. Neonatal acne occurs in newborns from birth to 6 weeks of age. Neonatal acne is estimated to affect 20% of newborns. Neonatal acne takes the form of comedones (whiteheads and blackheads) that extend from the scalp, upper chest, and back, and inflammatory lesions (erythematous papules and pustules) on the cheeks, chin, and forehead. Neonatal acne can be mistaken for neonatal cephalic pustulosis. Neonatal acne does not usually result in scarring. It is more likely to affect boys more than girls, at a rate of 5:1. Neonatal acne is thought to be a result of hyperactive sebaceous glands responding to neonatal androgens and maternal androgens that have crossed through the placenta. Androgen levels wane after approximately 1 year. At around 7 years of age, androgen production restarts, with the onset of adrenarche. From birth to around 12 months of age, luteinising hormone levels are similar to those during puberty. In males, this results in increased testosterone production and may explain the higher incidence of acne in boys of this age compared to girls. Sebum production leads to increased colonisation of the hair follicles by the acne bacteria, Cutibacterium acnes (previously called Propionibacterium acnes) and, as in adult acne, this results in follicular obstruction by sebum and keratin debris, and to inflammation.

- Infantile acne (see below)

- Mid-childhood acne. Mid-childhood acne affects children 1–6 years of age. Acne in this age group is very rare. An endocrinologist should be consulted to exclude possible hyperandrogenism. In pre-pubertal children with acne, a clinical history and examination may detect accelerated growth, early sexual development, and signs of hyperandrogenism, such as hirsutism. A bone-age X-ray of the left hand and a wrist X-ray should be considered for children with indications of accelerated growth.

- Preadolescent acne. Preadolescent acne affects children age 7–12 years (or up to menarche if female). Acne can be the first sign of puberty, and it is common to find acne in this age group. Preadolescent acne often presents as comedones in the ‘T-zone’, the region of the face covering the central forehead and the central part of the face (eg, the brow, nose, and lips).

The majority of children with acne will not require further investigations. However, if the findings on a clinical history and examination in children aged 1–6 years old indicate that further investigation is required, or if the acne is severe or unresponsive to treatment, an endocrinology referral may be required. The levels of the following hormones should be measured:

- Free and total testosterone

- Dehydroepiandrosterone

- Luteinizing hormone (LH)

- Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)

- Prolactin

- 17-hydroxyprogesterone.

Treatment for children with acne is generally the same as for adults with acne, with the exception of restrictions by age for tetracyclines. All treatments take at least 1–2 months to result in significant improvement.

Treatment of mild acne

The general management of mild acne involves gently washing the skin twice daily and using oil-free moisturizers. Avoid greasy emollients, hair pomades, and the use of comedogenic products on the affected area.

- Benzoyl peroxide: Benzoyl peroxide is a topical antiseptic and is available as a wash, gel, or lotion that can be bought over the counter. It can be used alone for mild acne or in combination with oral therapy for more severe cases. Benzoyl peroxide should be applied to all the areas affected by acne. If the skin is particularly sensitive, benzoyl peroxide treatment can be started at a low concentration of 2.5%, as higher concentrations are more likely to cause dryness and irritation.

- Topical retinoids — tretinoin and adapalene: Topical retinoids are creams, lotions, and gels enriched with a derivative of vitamin A (eg, tretinoin and adapalene). If the skin is sensitive, an oil-free moisturiser or sunscreen can be added. A topical retinoid should be applied to the whole of the affected skin. It is often initially used 2–3 times a week, and applications are increased to daily, as tolerated, if there is no improvement in the acne. Topical retinoids are also available in combination with benzoyl peroxide or a topical antibiotic.

Treatment of moderate acne

The treatment for children with moderate acne is 250–500 mg of the oral antibiotic, erythromycin, in single or split dosing. Erythromycin is best used in combination with a topical regimen, such as benzoyl peroxide and/or a topical retinoid, to reduce Cutibacterium acnes (previously called Propionibacterium acnes) resistance.

Trimethoprim and combined trimethoprim and sulphamethoxazole, have both been used if there is bacterial resistance to erythromycin or if erythromycin is contraindicated due to adverse effects. Doxycycline and minocycline should be used only in children over 12 years of age.

Isotretinoin is sometimes used in moderate acne when antibiotics and topical therapy have been unsuccessful.

Treatment of severe acne

The treatment of severe acne is the same as for moderate acne. Isotretinoin can be prescribed if there is an inadequate response to oral antibiotics. Doses of isotretinoin ranging from 0.2 to 1 mg/kg/day have been used safely in infants from 5 months of age and in children with severe acne. The isotretinoin capsules can be frozen to make it easier to divide them into halves or quarters, and freezing can help mask the unpleasant taste.

Premature epiphyseal closure is a theoretical concern with isotretinoin, but this has only been reported once when isotretinoin was used to treat acne in a 14-year-old boy at a dose of 0.75 mg/kg/day.

Deep nodules can be treated by injections with low-concentration intralesional triamcinolone acetonide at a dose of 2.5 mg/mL.

Infantile acne

Infantile acne is rare. Infantile acne occurs in infants up to 16 months of age and presents as comedones (whiteheads and blackheads), papules, pustules, occasional nodules and cysts 9. True infantile acne generally affects the cheeks, and sometimes the forehead and chin, of children aged six weeks to one year 9. Infantile acne is more common in boys than girls at a rate of 3:1 and is usually mild to moderate in severity. Severe infantile acne may result in permanent scarring. In most children it settles down within a few months. Individuals with severe infantile acne tend to develop troublesome acne at puberty, but it is not associated with underlying endocrine abnormalities.

The cause of infantile acne is unknown 9. It is thought to be genetic in origin. Infantile acne is not usually due to excessive testosterone or other androgenic hormones and children with infantile acne are usually otherwise quite normal in appearance.

Acne is rare in older prepubertal children aged 2 to 6. It is associated with higher levels of androgens than is expected for the age of the child. These may result in virilisation. Signs of virilisation are 9:

- Excessive body hair

- Abnormal growth

- Genital and breast development

- Body odor.

Hormone abnormalities in children with acne may be associated with the following conditions:

- Congenital adrenal hyperplasia

- Cushing syndrome

- 21-Hydroxylase deficiency

- Precocious puberty

- Androgen-secreting tumours

- Medications

- Premature adrenarche (early puberty).

In most babies with acne, no investigations are necessary. In older children, or if there are other signs of virilisation, the following screening tests may be useful.

- Blood tests: DHEAS, testosterone, 17-hydroxyprogesterone, LH, FSH, prolactin

- X-ray: bone age measurement

Treatment of infantile acne is usually with topical agents such as benzoyl peroxide or erythromycin gel. In severe cases, oral antibiotics such as erythromycin and trimethoprim, or isotretinoin may be required.

NOTE: Tetracycline antibiotics should NOT used in young children because they may cause yellow staining of the developing permanent teeth.

Figure 6. Infantile acne

Comedonal acne

Doctors refer to enlarged or plugged hair follicles as comedones. Comedonal acne is a pattern of acne in which most lesions are comedones, which are the skin-colored, small bumps (papules) frequently found on your forehead and chin. A single lesion is called a comedo.

Comedones arise when cells lining the sebaceous duct proliferate (cornification), and there is increased sebum production. A comedo is formed by the debris blocking the sebaceous duct and hair follicle. It is now known that comedones also involve inflammation (see causes of acne).

Types of comedonal acne:

- Open comedones are blackheads; black because of surface pigment (melanin), rather than dirt

- Closed comedones are whiteheads; the follicle is completely blocked

- Microcomedones are so small that they are not visible to the naked eye

- Macrocomedones are facial closed comedones that are larger than 2–3 mm in diameter

- A giant comedo is a type of cyst in which there is a clear blackhead-like opening in the skin

- Solar comedones are found on the cheeks and chin of older people, and are thought to be due to sun damage

The development of comedones may involve the following factors:

- Excessive activity of the male sex hormone 5-testosterone (DHT) within skin cells

- Reduced linoleate (the salt of the essential fatty acid, linoleic acid) in sebum causing more scale and reduced barrier function

- Proinflammatory cytokines (cell signalling proteins), such as Interleukin 1 (IL-1) and IL-8, produced by cells lining the follicle in response to activation of the innate immune system

- Free fatty acids made from sebum by acne bacteria

- Overhydrated skin premenstrually, from moisturisers or in humid conditions

- Contact with certain chemicals including oily pomades, isopropyl myristate, propylene glycol and some dyes in cosmetics

- Rupture of the follicle by injury such as squeezing pimples, abrasive washing, chemical peels or laser treatments

- Smoking – comedonal acne is more common in smokers than in non-smokers

- Certain dietary factors may contribute to comedonal acne, particularly milk products and high glycemic-index foods (sugars and fats)

If you have comedonal acne, choose oil-free cosmetics (use water-based non-comedogenic products, as they’re less likely to block the pores in your skin) and wash twice daily with a mild soap and water 10. It is best to stop smoking and to have a diet that is low in sugar, fat and dairy products.

Choose “comedolytic” topical medications. These should be applied once or twice daily as a thin smear to the entire area affected. It may take several weeks to months before worthwhile improvement occurs. Treatment needs to be continued long-term (sometimes for many years).

Suitable topical agents include 10:

- Benzoyl peroxide

- Azelaic acid

- Salicylic acid +/- sulfur and resorcinol

- Glycolic acid

- Retinoids such as tretinoin, isotretinoin, adapalene (these require a doctor’s prescription)

Prescription oral medications for comedonal acne include 10:

- Hormonal therapy

- Isotretinoin

Antibiotics can also improve comedonal acne but are usually prescribed for inflammatory acne (acne vulgaris).

Surgical treatments are sometimes recommended to remove persistent comedones 10:

- Cryotherapy

- Electrosurgery (cautery or diathermy)

- Microdermabrasion

Figure 7. Comedonal acne

Acne excoriee

Acne excoriée also called acne excorie is a term used to describe scratched or picked pimples. Acne excoriée results when acne lesions are compulsively squeezed and scratched, resulting in scabs and scars. Acne excoriée is uncommon and occurs particularly in young females than males, particularly women with late-onset acne. There are two reasons for acne excoriée presenting:

- Very occasionally patients with very mild acne just pick acne spots in the belief that simply by so doing that will help the acne. A simple explanation from the doctor of the harm that they are doing can help considerably

- In the other subgroup, the majority, there may be underlying psychological problems, which are often difficult to unravel. There may even be no pathological acne lesions, the patient just scratches the skin – such patients may be considered to have dermatitis artifacta and/or the body dysmorphic disorder (bodily focused anxiety). Such patients should be referred for psychological assessment and management.

Anyone who gets acne can suffer from acne excorie. Spending hours in front of the mirror can also be a sign of stress or depression. Psychiatrists may classify acne excorie with body dysmorphic disorder (bodily focused anxiety).

Sometimes it is just a bad habit that’s hard to break; the acne may not actually be all that severe. In fact there seems to be two subgroups of acne excorie patients – one where patients have primary acne lesions and those who have none or hardly any acne lesions.

Acne excorie can be very upsetting and embarrassing. Most people squeeze or pick some of their spots in an attempt to be rid of them. This can makes the acne look worse. The acne may become secondarily infected and picking it may also cause scarring.

Some individuals excessively pick their spots. When their skin is examined, they have no active acne spots, only scratch marks, sores, pigmentation and scars. All the inflammatory lesions and comedones have been removed by picking or squeezing. This appearance is called acne excorie.

Most people are aware that their facial sores are due to skin picking, but they do not always admit to it openly.

Treatment of acne excorie depends on whether or not the patient has primary acne lesions. Active acne spots can be managed using acne treatment depending on their clinical severity.

Some patients with acne excorie may just need to break the habit of picking, whilst other patients may have a compulsive skin picking disorder. This may require psychological therapy and psychotropic drug treatments.

Figure 8. Acne excorie

Footnote: This patient had small amounts of acne, but her picking resulted in scars.

Nodulocystic acne

Nodulocystic acne is a severe form of acne affecting the face and upper trunk, characterized by nodules and cysts that typically resolve with scarring 11. Nodulocystic acne is usually a disorder of adolescence and early adult life seen most commonly in males. However there is a rare juvenile form with onset before 6 years of age, also with a male predominance. No studies have shown an increased incidence in specific racial groups.

Nodulocystic acne is associated with other follicular occlusion disorders particularly hidradenitis suppurativa. Nodulocystic acne typically persist into adult life. Unless treated early and effectively, nodulocystic acne results in scarring particularly on the trunk.

Acne conglobata is a rare severe form of nodulocystic acne. It presents with groups of multiple comedones and inflammatory papules, pustules, and nodules involving the trunk, limbs, and buttocks. Interconnecting abscesses and draining sinuses become secondarily infected causing pain and malodour. Healing is slow, leaving unsightly hypertrophic and atrophic scars. Acne conglobata is often very persistent, lasting into the 30s or 40s.

Nodulocystic acne is a clinical diagnosis. Hormone studies may be considered in the presence of suggestive clinical features.

Topical treatment is usually ineffective for nodulocystic acne. The recommended treatment is oral isotretinoin which should be commenced early to prevent scarring. Treatment is required for at least five months, and further courses are sometimes necessary. Intralesional steroids following cyst drainage, can be used for individual persistent or large inflammatory nodules or cysts.

Patients with acne conglobata often need additional treatments, such as 11:

- Oral antibiotics for secondary bacterial infection

- Systemic corticosteroids to reduce inflammation

- Adalimumab, used off-label, for resistant severe disease.

Figure 9. Nodulocystic acne

Acne fulminans

Acne fulminans is a rare and very severe form of acne conglobata associated with systemic symptoms such as a fever, arthritis and lethargy 12. Acne fulminans nearly always affects adolescent males. It typically presents in mid-teenage boys who may have had, for a few years, mild acne which, over a matter of a few weeks changes into severe inflammatory acne, especially on the trunk 13.

Acne fulminans is characterized by 12:

- Abrupt onset

- Inflammatory and ulcerated nodular acne on chest and back, which is painful

- Bleeding crusts over the ulcers on upper trunk

- Severe acne scarring

- Fluctuating fever

- Painful joints, including sacroiliac joints in 20% of cases, ankles, shoulders, and knee joints

- Malaise (i.e. the patient feels unwell)

- Loss of appetite and weight loss

- Enlarged liver and spleen.

Tests typically reveal 12:

- Anemia (lowered hemoglobin count)

- Raised white blood cell count

- Raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein levels

- X-rays may show osteolytic bone lesions.

Acne fulminans has been associated with increased androgens (male hormones), autoimmune complex disease and genetic predisposition. It may be related to an explosive hypersensitivity reaction to surface bacteria (Cutibacteria acnes). Acne fulminans may be precipitated by:

- Testosterone and anabolic steroids (legally prescribed or illegally taken to enhance muscle growth)

- Oral isotretinoin.

The syndrome SAPHO (Synovitis, Acne, Pustulosis, Hyperostosis and Osteitis) may be a serious complication of acne fulminans.

Patients with acne fulminans should consult a dermatologist urgently – a delay in treatment results in severe scarring. Management can prove difficult, and several medications are usually required for several months or longer. These may include:

- Systemic corticosteroids such as prednisone (20–60 mg/day)

- Anti-inflammatory medications such as salicylates (aspirin)

- Dapsone 50–100 mg/day

- Ciclosporin

- High doses of oral antibiotics such as erythromycin (2 g/day) for secondary infection

- Isotretinoin commenced in low dose after control has been obtained with systemic steroids

- Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) inhibitors, such as infliximab.

Topical acne medications are unhelpful. First-line treatment is usually oral steroids, followed by the introduction of low dose oral isotretinoin, hospitalization may be required.

Figure 10. Acne fulminans

Acne scars

Acne scars are usually the result of inflamed blemishes caused by skin pores engorged with excess oil, dead skin cells and bacteria. The pore swells, causing a break in the hair follicle wall. Shallow lesions are usually minor and heal quickly. But if there is a deep break in the wall of the pore, infected material can spill out into surrounding tissue, creating deeper lesions. The skin attempts to repair these lesions by forming new collagen fibers. These repairs usually aren’t as smooth and flawless as the original skin. The term “scarring” refers to a fibrous process in which new collagen is laid down to heal a full-thickness injury. Acne scarring affects 30% of those with moderate or severe acne vulgaris. It is particularly common in nodulocystic acne, acne conglobata and acne fulminans. It may also be a long-term consequence of infantile acne. Picking at or manipulating acne lesions can also increase the chance of scarring.

There are two main types of acne scars:

- Hypertrophic or keloid scarring: These scars are caused when the body produces too much collagen as acne wounds heal, resulting in a mass of raised tissue on the skin’s surface.

- Atrophic or depressed scarring: These scars develop when there is a loss of tissue. There are two common types of atrophic scarring. “Icepick” scars are usually small, yet obvious holes in the skin. “Boxcar” scars are depressed areas, usually round or oval in shape with steeply angled sides, similar to chickenpox scars.

To reduce the chance of scarring, seek treatment for your acne early. Severe acne can often be cured.

Studies have shown that people with acne scars can suffer physically, emotionally and socially. Likewise, those who have received successful treatment enjoy an improved appearance, enhanced self-esteem and promotion of better skin health.

Figure 11. Acne scarring

Chloracne

The name “chloracne” is misleading, because it is not related to acne. A more correct terminology is “MADISH”—Metabolising Acquired Dioxin Induced Skin Hamartomas. Rather than overactive sebaceous glands, as occurs in acne, the sebaceous glands concentrate the responsible chemical and metabolize it extremely slowly. This process alters gene expression in the sebaceous glands and changes them from functioning grease-producing glands into the skin cysts (hamartomas) of chloracne.

Chloracne is a rare skin condition caused by certain toxic halogenated aromatic hydrocarbon chemicals, including the dioxins, which are most often found in 14:

- Fungicides

- Insecticides

- Herbicides

- Wood preservatives

Chloracne is the most common skin sign of dioxin poisoning. Responsible chemicals include 14:

- Chlornaphthalene

- Polychlorbiphenyls (PCBc)

- Polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins (PCDDs)

- Polychlorinated dibenzofurone (PCDFs)

- Chlorophenol contaminants

- Trifluoromethyls

- Pyrazole derivatives

- Chlorobenzene

Chloracne develops a few months after swallowing, inhaling or touching the responsible agent. Most cases of chloracne are due to occupational exposure but chloracne can also arise after accidental environmental poisoning. One hundred and ninety-three cases of chloracne resulted from an industrial accident in Seveso, Italy in 1976. Deliberate dioxin poisoning is blamed for Ukrainian President Victor Yushchenko’s changed appearance in September 2004. Very low level dioxin and dioxin-like aromatic hydrocarbons are ubiquitous in the environment but standard environmental exposure does not result in chloracne.

The features of chloracne are 14:

- Open and closed comedones (whiteheads and blackheads)

- Uninflamed nodules and cysts

The lesions are most often seen on the cheeks, behind the ears, in the armpits and in the groin. Although they resemble acne, the skin is not usually oily; in fact the oil glands are often smaller than usual.

Other skin problems seen in patients with chloracne include 14:

- Sweaty palms and soles (hyperhidrosis)

- Porphyria cutanea tarda (pigmentation, increased hair growth and blisters on exposed skin)

Other health problems may include:

- Abnormal liver function

- Tiredness (sleep disturbance)

- Nerve conditions (transient peripheral neuropathy, and encephalopathy – this can result in poor concentration and depression)

- High levels of circulating blood fats (hyperlipidaemia)

- Impotence

- Type 2 diabetes

The data for an association with other health problems and birth defects are conflicting.

The diagnosis of chloracne is mostly on the grounds of history and expert clinical opinion. Biopsies of affected skin may show a reduction of the normal sebaceous gland density and development of the skin hamartomas. Immunohistochemical tests (eg CYP1A1) can be done on the hamartomas to determine up or down-regulation of gene expression to support the clinical diagnosis.

Once chloracne has been recognized, the source of exposure must be identified and the affected individual and other workers must be removed from exposure to it. Occupational disease due to chemical exposure is a notifiable condition.

Most chloracne lesions clear up within 2 years providing exposure to the chemical has stopped. In some cases they persist much longer because the chemical continues to be slowly released from fat cells.

Persistent cases may be helped by standard treatments for acne, particularly oral antibiotics and sometimes isotretinoin. Comedones and cysts can be punch excised or cauterized.

Figure 12. Chloracne

What causes acne?

Acne or acne vulgaris is a chronic inflammatory skin disease originating within the pilosebaceous follicles (hair follicles) due to a combination of factors. No one knows exactly what causes acne, but doctors and researchers believe that one or more of the following can lead to the development of acne 15, 16:

- sebum (an oily secretion of the sebaceous glands) overproduction,

- abnormal shedding of follicular epithelium,

- follicular colonization by Cutibacterium acnes (previously called Propionibacterium acnes), and

- inflammation. This is a complex process involving an interaction between:

- Biological changes occurring in the duct as a result of comedone formation and Cutibacterium acnes colonization of the duct

- And the patients cellular (especially lymphocytes) response within the dermis, which responds to pro-inflammatory cytokines spreading from the duct to the dermis

In healthy skin, the sebaceous glands (oil glands) make sebum that empties onto the skin surface through the pore, which is an opening in the hair follicle. Keratinocytes, a type of skin cell, line the hair follicle. Normally as the body sheds skin cells, the keratinocytes rise to the surface of the skin. When someone has acne, the hair, sebum, and keratinocytes stick together inside the pore. This prevents the keratinocytes from shedding and keeps the sebum from reaching the surface of the skin. The mixture of oil and cells allows bacteria that normally live on the skin to grow in the plugged follicles and cause inflammation—swelling, redness, heat, and pain. When the wall of the plugged follicle breaks down, it spills the bacteria, skin cells, and sebum into nearby skin, creating lesions or pimples.

Sebum overproduction is the result of endogenous and exogenous androgenic hormones or a heightened sebaceous gland sensitivity to normal levels of androgen hormones 16. Inflammatory pathway activation is evident at all stages of acne progression 16. There may also be a genetic component or familial tendency to acne 17. Certain foods and drinks, particularly those with a high glycemic index (e.g., sugary drinks, starchy foods, highly processed foods) and skim milk, seem to affect acne severity 18, 19. Other factors that may be involved in the development or progression of acne include psychological stress 20, tobacco smoke 21 and damaged or unhealthy skin 22.

The following factors may increase your risk for developing acne 23:

- Polycystic ovarian disease (PCOS) – a common condition that can cause acne, weight gain and the formation of small cysts inside the ovary

- Acne in women. Women are more likely to have adult acne than men. It’s thought that many cases of adult acne are caused by the changes in hormone levels that many women have at certain times. These times include:

- periods – some women have a flare-up of acne just before their period

- pregnancy – many women have symptoms of acne at this time, usually during the first 3 months of their pregnancy

- polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)

- Hormones. An increase in androgens, which are male sex hormones, may lead to acne. These increase in both boys and girls normally during puberty and cause the sebaceous glands to enlarge and make more sebum. Hormonal changes related to pregnancy can also cause acne.

- Age. People of all ages can get acne, but it is more common in teens.

- Medications: steroids (corticosteroids), hormones, anticonvulsants, epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors, lithium (used to treat depression and bipolar disorder), ciclosporin, iodides and others, can cause acne.

- Application of occlusive cosmetics, especially oil-based products, suntan lotion, and hair products.

- Family history. Researchers believe that you may be more likely to get acne if your parents had acne. One study has found that if both your parents had acne, you’re more likely to get more severe acne at an early age. It also found that if one or both of your parents had adult acne, you’re more likely to get adult acne too.

- High environmental humidity

- Smoking

- Regularly wearing items that place pressure on an affected area of skin, such as a headband or backpack

- Diet high in dairy products and high glycemic index (GI) foods. Eating a healthy, balanced diet is recommended because it’s good for your heart and your health in general.

The following do not cause acne, but may make it worse.

- Diet. Some studies show that eating certain foods may make acne worse. Researchers are continuing to study the role of diet as a cause of acne.

- Stress.

- Pressure from sports helmets, tight clothes, or backpacks.

- Environmental irritants, such as pollution and high humidity.

- Squeezing or picking at blemishes.

- Scrubbing your skin too hard.

Acne prevention

Acne cannot be prevented or avoided. However, some people can reduce the severity by knowing what triggers the irritation. Because boys have more skin oils, they tend to have more severe acne. They have more skin oils. For many people, acne disappears by the age of 25. However, it can continue well into adulthood.

Certain things can trigger or make acne worse:

- Hormonal changes. This happens during puberty, before a woman’s period (menstrual cycle), during pregnancy, or during menopause.

- Certain medicines. This includes supplements or steroids that increase testosterone.

- Makeup (cosmetics), especially oil-based products, suntan lotion, and hair products.

- Stress. Stress doesn’t cause acne, but stress can make it worse.

- Picking or squeezing existing pimples.

- Scrubbing your skin too harshly.

- Certain foods, including sugary drinks, white breads and rice, have been shown to increase acne.

You can help prevent acne flare-ups and scars by taking good care of your skin:

- Clean your skin gently with a mild soap or cleanser twice a day — once in the morning and once at night. You should also gently clean the skin after heavy exercise. Avoid strong soaps and rough scrub pads. Harsh scrubbing of the skin may make acne worse. Wash your entire face from under the jaw to the hairline and rinse thoroughly. Remove make-up gently with a mild soap and water. Ask your doctor before using an astringent.

- Completely remove make-up before going to bed.

- Wash your hair on a regular basis. If your hair is oily, you may want to wash it more often.

- Do not squeeze or pick at acne lesions. This can cause acne scars.

- Avoid getting sunburned. Many medicines used to treat acne can make you more prone to sunburn. Many people think that the sun helps acne, because the redness from sunburn may make acne lesions less visible. But, too much sun can also increase your risk of skin cancer and early aging of the skin. When you’re going to be outside, use sunscreen of at least SPF 15. Also, try to stay in the shade as much as you can.

- Choose water-based make-up and hair care products that are “non-comedogenic” or “non-acnegenic.” These products have been made in a way that they don’t cause acne. You may also want to use products that are oil-free.

- Avoid things that rub the skin as much as you can, such as backpacks and sports equipment.

- If dry skin is a problem, use a fragrance-free water-based emollient.

- Talk with your doctor about what treatment methods can help your acne. Take your medicines as prescribed. Be sure to tell your doctor if you think medicines you take for other health problems make your acne worse.

Symptoms of acne

Symptoms of acne may include:

- Small, raised, red spots.

- White, fluid-filled tips on the spots.

- Blackheads (looks like pepper in your pores).

- Solid, tender lumps under the skin.

Acne complications

Complications of acne vulgaris may include:

- Postinflammatory dyspigmentation. Postinflammatory color changes are seen after inflammatory acne lesions have recently healed. Postinflammatory color changes improve with time, but it can take many months for them to completely resolve.

- Postinflammatory erythema – pink or purple flat patches

- Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation – brown marks (pigmentation), seen in people who can tan easily

- Postinflammatory hypopigmentation – white marks

- Treatments for postinflammatory pigmentation include:

- Careful sun protection – even though inflammatory acne lesions may improve, brown marks darken with sun exposure. Apply a broad-spectrum oil-free sunscreen and wear a broad-brimmed hat when outdoors

- Azelaic acid cream – this reduces pigmentation as well as effectively treating mild to moderate acne

- Hydroquinone bleaching creams – these inhibit the enzyme tyrosinase that causes tanning

- Superficial chemical peels containing glycolic acid or Jessner solution.

- Scarring, including keloid scars. The following types of scar occur in acne:

- Ice-pick scars – these are deep, narrow, pitted scars

- Rolling scars – broad depressions with a sloping edge

- Boxcar scars – broad depressions with sharply defined edges

- Atrophic scars – flat, thin scars or depressed scars (anetoderma)

- Hypertrophic or keloid scars – thick lumpy scars.

- Psychological effects of acne. The psychological and social impacts of acne are a huge concern, especially because acne affects adolescents at a crucial period when they are developing their personalities. During this time, peer acceptance is very important to the teenager and unfortunately it has been found that there are strong links between physical appearance and attractiveness and peer status. The following are some of the problems that patients with acne may face:

- Self esteem and body image

- Some embarrassed acne patients avoid eye contact.

- Some acne sufferers grow their hair long to cover the face. Girls tend to wear heavy make-up to disguise the pimples, even though they know that this sometimes aggravates their acne. Boys often comment: “Acne is not such a problem for girls because they can wear make-up”.

- Truncal acne can reduce participation in sport such as swimming or rugby because of the need to disrobe in public changing rooms.

- Social withdrawal/relationship building

- Acne, especially when it affects the face, provokes cruel taunts from other teenagers.

- Some find it hard to form new relationships, especially with the opposite sex.

- At a time when teenagers are learning to form relationships, those with acne may lack the self confidence to go out and make these bonds. They become shy and even reclusive. The main concern is a fear of negative appraisal by others. In extreme cases a social phobia can develop.

- Education/work

- Some children with acne refuse to go school, leading to poor academic performance.

- Some people with acne take sick days from work, risking their jobs or livelihood.

- Acne may reduce career choices, ruling out occupations such as modelling that depend upon personal appearance.

- Acne patients are less successful in job applications; their lack of confidence being as important as the potential employers’ reaction to their spotty skin.

- More people who have acne are unemployed than people who do not have acne.

- Many young adults with acne seek medical help as they enter the workforce, where they perceive that acne is unacceptable and that they “should have grown out of it by now”.

- In some patients the distress of acne may result in depression. This must be recognized and managed. Signs of depression include:

- Loss of appetite

- Lethargy

- Mood disturbance

- Behavioral problems

- Wakefulness

- Spontaneous crying

- Feelings of unworthiness.

- In teenagers, depression may manifest as social withdrawal (retreat to the bedroom or avoidance of peers) or impaired school performance (lower grades or missed assignments). Severe depression from acne has resulted in attempted suicide and, unfortunately, successful suicide. Worrying statements include: “I don’t want to wake up in the morning”; “I’d be better off dead”; “I’m worthless”; “You’d be better off without me”. Parents, friends and school counsellors need to take heed when they start to hear these types of comments.

- Rarely, depression can be associated with acne treatment, particularly isotretinoin. There is much controversy about whether the drug causes depression. However, it is clear that depression often results from acne and the psychological disturbances described above.

- Regardless of the cause, depression must be recognized and managed early. If you think you or someone you know may be depressed, contact your dermatologist or family doctor urgently for advice.

- Self esteem and body image

If your acne is interfering significantly with your life, particularly if it is resulting in any of the problems described above, seek help promptly from your family physician and/or dermatologist. Tell your doctor all your concerns, so that he or she will take your acne seriously. Most cases of acne can be controlled and sometimes cured with treatment, using one or more of the following preparations:

- Over-the-counter topical acne creams, lotions or gels for mild cases

- Prescription medications, both topical and oral, that are available only through a physician, for more severe cases

Depression is an illness that can nearly always be treated effectively. See your doctor for advice and if necessary, you may be referred to a health professional specializing in mental illness.

Suitable treatments for depression may include:

- Talking therapies such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)

- Antidepressant medication called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

- Psychological treatments to overcome the negative thinking, anxiety and avoidance that often accompany depression

- Counselling to help build confidence and rebuild self-esteem.

- Group therapy

It is particularly important that a teenager’s anxiety over their acne is managed appropriately.

How is acne diagnosed?

Most of the time, your doctor can diagnose acne by examining the irritation on your skin. He or she will also consider your age, lifestyle, or circumstances. For example, some women get acne when they are pregnant. Some teens and adults get acne from certain foods.

To diagnose acne, doctors may:

- Ask about your family history, and, for girls or women, ask about their menstrual cycles.

- Ask you about your symptoms, including how long you have had acne.

- Ask what medications you are currently taking or recently stopped.

- Examine your skin to help determine the type of acne lesion.

- Order lab work to determine if another condition or medical disorder is causing the acne.

- Skin swabs for microscopy and culture

- Hormonal tests in females. Clinically, patients with hormone-related acne can be recognized by the concentration of lesions along the jaw line and chin 24. It has been seen that more than 50% of adult female patients of persistent acne have at least one abnormal hormonal level 25. A hormonal evaluation is reserved for those patients who experience the following 15:

- Therapy-resistant acne, especially those who fail to respond to isotretinoin therapy or relapse shortly after discontinuing isotretinoin or oral contraceptives (OCs) 26

- Those who develop late-onset (adult acne, after 35 years of age) or sudden-onset, or severe, unresponsive, and persistent acne 27

- Prepubertal acne 28

- History of premenstrual flare 29

- Stress exacerbated acne 30

- Associated signs of hyperandrogenism, such as hirsutism, androgenetic alopecia, seborrhea, or SAHA syndrome (seborrhea, acne, hirsutism, and androgenetic alopecia) 27

- Patients with associated signs of virilization like male body contour, deepening of voice, cliteromegaly, hirsutism, etc 31

- Females with history suggestive of polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) like menstrual irregularities, infertility, weight gain, and insulin resistance 27

- HAIR-AN syndrome (hyperandrogenism, insulin resistance, and acanthosis nigricans) 27

- Associated with cutaneous signs of hyperinsulinemia, such as acanthosis nigricans, skin tags, mid-truncal obesity, etc.

- Total testosterone and SHBG levels should be checked in patients suspected of having Polycystic Ovarian syndrome (PCOS), which may be suggested by oligomenorrhoea (less than nine periods a year) and/or hirsutism.

- If a patient with mild hyperandrogenism does not have PCOS then consider late onset (non-classical) congenital adrenal hyperplasia.

- For patients suspected of having more serious pathology, including those found to have repeat testosterone levels > 4.8 nmol/l (preferably measured in the first 5 days of the menstrual cycle) and/or other features of virilization.

Acne vulgaris differential diagnosis

- Acne cosmetica: Associated with use of heavy oil-based hair products and cosmetics and resolves with discontinuation of these products.

- Drug-induced acne: Monomorphic lesions and history of medication use (glucocorticoids, lithium, oral contraceptives, phenytoin [Dilantin], isoniazid, androgens).

- Folliculitis: Monomorphic lesions, abrupt onset and variable distribution with absence of comedones, spreads with scratching or shaving.

- Hidradenitis suppurativa: Double-headed comedones (two pustules), inflamed nodules with abscesses, predilection for intertriginous areas, sinus tracts.

- Miliaria: Nonfollicular papules, pustules, and vesicles; occurs in response to heat or exertion.

- Perioral dermatitis: Papules, pustules, and erythema confined to the chin and nasolabial folds with sparing of the area directly adjacent to the vermilion border.

- Pseudofolliculitis barbae: Occurs in bearded areas with short, curly hair that is shaved closely.

- Rosacea: Erythema and telangiectasia, absence of comedones.

- Seborrheic dermatitis: Greasy scales with yellow-red, coalescing macules and papules.

Acne treatment

The goal of acne treatment is to help heal existing lesions, stop new lesions from forming, and prevent scarring. Medications can help stop some of the causes of acne from developing, such as abnormal clumping of cells in the follicles, high sebum levels, bacteria, and inflammation. Your doctor may recommend over-the-counter (OTC) or prescription medications to take by mouth or apply to the skin.

Figure 13. Severity-based approach to treating acne vulgaris

[Source 5 ]Table 1. Nonantibiotic topical agents for the treatment of acne vulgaris

| Medication* | Adverse effects | Pregnancy/children† | Cost‡ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Azelaic acid (Azelex, Finacea)§ | Burning, dryness, stinging, erythema, pruritus, hypersensitivity reaction, asthma exacerbation, hypopigmentation in individuals with dark skin | May use during pregnancy; no human data available, although risk of fetal harm is not expected based on minimal systemic absorption Safety and effectiveness not established in children younger than 12 years | 20% cream: — ($680) for a 50-g tube 15% gel: $120 ($345) for a 50-g tube |

| Benzoyl peroxide | Burning, dryness, stinging, erythema, peeling, hypersensitivity, bleaching of hair or clothing | May use during pregnancy; inadequate human data available, although risk of fetal harm is not expected based on minimal systemic absorption Safety and effectiveness not established in children younger than 12 years | Variable cost based on over-the-counter vs. prescription, brand vs. generic, formulation (many available), and size |

| Dapsone (Aczone) | Burning, dryness, erythema, pruritus, orange staining of skin | May use during pregnancy; no human data available, although risk of fetal harm is not expected based on minimal systemic absorption Safety and effectiveness not established in children younger than 12 years | 5% gel: $250 ($665) for a 60-g tube 7.5% gel: — ($665) for a 60-g tube |

Footnotes:

* All applied twice per day.

† Information from Epocrates.

‡ Estimated retail price based on information obtained at https://www.goodrx.com. Actual cost will vary with insurance and by region. Generic price listed first; brand in parentheses.

§ Although the 15% gel is not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for acne vulgaris, this formulation has greater bioavailability.

[Source 4 ]Table 2. Topical antibiotics for the treatment of acne vulgaris

| Medication* | Adverse effects | Pregnancy/children† | Cost‡ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clindamycin 1% (Cleocin, Evoclin) | Pruritus, erythema, dryness, peeling, Clostridium difficile colitis, folliculitis, photosensitivity | May use during pregnancy; no human data available, although risk of fetal harm is not expected based on minimal systemic absorption Safety and effectiveness not established in children younger than 12 years | Gel: $70 ($285) for a 60-g tube Lotion: $50 ($220) for 60-mL bottle Solution: $30 ($150) for a 60-mL bottle Foam: $190 ($500) for a 50-g can |

| Clindamycin 1%/benzoyl peroxide 5% (Benzaclin) | Pruritus, erythema, dryness, peeling, C. difficile colitis, anaphylaxis | May use during pregnancy; no human data available, although risk of fetal harm is not expected based on expected limited systemic absorption Safety and effectiveness not established in children younger than 12 years | Gel: $70 ($190) for a 25-g jar |

| Erythromycin 2% (Erygel, Ery) | Dryness, irritation, C. difficile colitis | May use during pregnancy; no human data available, although risk of fetal harm not expected based on minimal systemic absorption Safety and effectiveness not established in children younger than 12 years | Gel: $70 ($12§) for a 60-g tube Solution: $25 (—) for a 60-mL bottle Pads: $40 ($40) for 60 pledgets |

| Erythromycin 3%/benzoyl peroxide 5% (Benzamycin) | Pruritus, erythema, dryness, peeling, burning, urticaria, C. difficile colitis | May use during pregnancy; no human data available, although risk of fetal harm is not expected based on minimal systemic absorption Safety and effectiveness not established in children younger than 12 years | Gel: $130 ($85) for a 46.6-g jar |

Footnotes:

* All applied twice per day, except for clindamycin 1% foam, which is applied once per day.

† Information from Epocrates.

‡ Estimated retail price based on information obtained at https://www.goodrx.com (accessed May 28, 2019). Actual cost will vary with insurance and by region. Generic price listed first; brand in parentheses.

§ Price obtained from Walgreens June 17, 2019.

[Source 4 ]Table 3. Topical retinoids for the treatment of acne vulgaris

| Medication* | Adverse effects | Pregnancy/children† | Cost‡ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adapalene (Differin) | Burning, peeling, stinging, pruritus, erythema, dryness, photosensitivity | May use during pregnancy; risk of fetal harm not expected based on limited human data and insignificant systemic absorption Approved for use in children 12 years and older | Cream: $100 ($380) for a 45-g tube 0.1% gel: $70 ($600) for a 45-g tube 0.3% gel: $100 ($360) for a 45-g tube Lotion: $300 ($350) for a 59-mL bottle |

| Adapalene/benzoyl peroxide (Epiduo) | Burning, peeling, stinging, pruritus, erythema, dryness, photosensitivity | May use during pregnancy; risk of fetal harm not expected based on limited human data and insignificant systemic absorption Approved for use in children nine years and older | 0.1%/2.5% gel: $80 ($360) for a 45-g pump 0.3%/2.5% gel: — ($480) for a 45-g pump |

| Clindamycin phosphate/tretinoin (Veltin, Ziana) | Burning, peeling, stinging, pruritus, erythema, dryness, photosensitivity, colitis | Consider avoiding use during pregnancy, especially in the first trimester Approved for use in children 12 years and older | 1.2%/0.025% gel: $300 ($740) for a 60-g tube |

| Tazarotene (Tazorac) | Burning, peeling, stinging, pruritus, erythema, dryness, photosensitivity | Use alternative during pregnancy Approved for use in children 12 years and older | 0.05% cream: — ($830) for a 60-g tube 0.1% cream: $250 ($875) for a 60-g tube 0.05% gel: — ($415) for a 30-g tube 0.01% gel: — ($440) for a 30-g tube |

| Tretinoin (Retin-A, Atralin) | Burning, peeling, stinging, pruritus, erythema, dryness, photosensitivity | Consider avoiding use during pregnancy, especially in the first trimester Approved for use in children 10 years and older | Cream (for a 45-g tube): 0.025%: $85 ($100) 0.05%: $100 ($100) 0.1%: $150 ($100) |

| Gel (for a 45-g tube): 0.01%: $90 ($100) 0.025%: $60 ($100) 0.05%: $200 ($600) | |||

| Microsphere (for a 45-g tube): 0.04%: $200 ($800) 0.1%: $200 ($800) |

Footnotes:

* All applied once per day.

† Information from Epocrates.

‡ Estimated retail price based on information obtained at https://www.goodrx.com. Actual cost will vary with insurance and by region. Generic price listed first; brand in parentheses.

[Source 4 ]Table 4. Oral antibiotics for the treatment of moderate to severe inflammatory acne vulgaris

| Medication | Dosage | Adverse effects | Pregnancy/children* | Cost† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline (Vibramycin, Acticlate) | Children: 2 mg per kg per dose every 12 hours on day 1, then 2 mg per kg once per day thereafter (maximum dose is 100 mg) Adults: 50 to 100 mg once or twice per day | Nausea, diarrhea, dyspepsia, esophagitis, headache, vaginal candidiasis, photosensitivity, tooth/bone discoloration, pseudotumor cerebri, hepatotoxicity, Clostridium difficile colitis | Avoid use during pregnancy Safety and effectiveness not established in children younger than eight years | $15 ($380) for 30 100-mg capsules $300 ($1,100) for 30 150-mg tablets |

| Erythromycin‡ | Children and adults: 250 to 500 mg two to four times per day | Nausea, vomiting, drug interactions, arrhythmias | May use during pregnancy; possible risk of fetal harm based on conflicting human data Safe for use in children | $480 (—) for 60 250-mg tablets |

| Minocycline (Minocin) | Children: 1 mg per kg once per day Adults: 50 mg one to three times per day | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, vestibular dysfunction, photosensitivity, hyperpigmentation, pseudotumor cerebri, lupus-like reaction, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms, hepatotoxicity, Stevens-Johnson syndrome | Avoid use during pregnancy Not indicated in children younger than eight years | $15 ($850) for 30 50-mg capsules $40 (—) for 30 50-mg tablets |

| Sarecycline (Seysara) | Children and adults 33 to 54 kg (73 to 119 lb): 60 mg per day 55 to 84 kg (121 to 185 lb): 100 mg per day 85 to 136 kg (187 to 300 lb): 150 mg per day Treat for 12 weeks then reassess | Nausea, lightheadedness, dizziness, vertigo, headache, vaginal candidiasis, photosensitivity, tooth/bone discoloration, pseudotumor cerebri, hepatotoxicity, C. difficile colitis | Avoid use during pregnancy or while breastfeeding Avoid use in children younger than nine years | — ($900) for 30 tablets of any strength |

| Tetracycline | Children: 25 to 50 mg per kg per day in two to four divided doses Adults: 250 to 500 mg once or twice per day | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, photosensitivity, tooth and nail discoloration, pseudotumor cerebri, hepatotoxicity, urticaria | Avoid use during pregnancy Not indicated in children younger than eight years | $70 (—) for 30 250-mg capsules |

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole‡ | Children and adults: 160/800 mg twice per day | Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, hepatotoxicity, bone marrow suppression, drug eruptions | Consider alternative during pregnancy; possible risk of spontaneous abortion based on limited human data; possible risk of congenital neural tube and cardiovascular defects based on conflicting human data and trimethoprim’s mechanism of action Safety and effectiveness not established in children younger than two months | $15 (—) for 60 160/800-mg tablets |

Footnotes:

* Information from Epocrates.

† Estimated retail price for one month’s treatment based on information obtained at https://www.goodrx.com. Actual cost will vary with insurance and by region. Generic price listed first; brand in parentheses.

‡ Not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of acne; off-label use.

[Source 4 ]Benzoyl peroxide

Benzoyl peroxide is comedolytic, anti-inflammatory, and bactericidal against Cutibacterium acnes (previously called Propionibacterium acnes) 32, 33. Benzoyl peroxide is available over the counter and by prescription in multiple strengths and formulations, and can be used alone or in combination with topical antibiotics or retinoids. Benzoyl peroxide is used either once or twice a day. It should be applied 20 minutes after washing to all of the parts of your face affected by acne. A reduction in acne lesion count may occur within days of initiating treatment with benzoyl peroxide. Most people need a 6-week course of treatment to clear most or all of their acne. You may be advised to continue treatment less frequently to prevent acne returning. Use of benzoyl peroxide itself does not induce bacterial resistance 1. Benzoyl peroxide is safe to use during pregnancy. Adverse effects of benzoyl peroxide include burning, dryness, stinging, redness, peeling, hypersensitivity, and bleaching of hair or clothing. Benzoyl peroxide also makes your face more sensitive to sunlight, so avoid too much sun and sources of ultraviolet (UV) light (such as sunbeds), or wear sun cream.

Topical antibiotics

Topical antibiotics, including clindamycin 1% and erythromycin 2%, are commonly used for the treatment of mild to moderate acne in combination with benzoyl peroxide 4. Topical antibiotics possess anti-inflammatory and, depending on the formulation, bacteriostatic or bactericidal properties 34. Clindamycin is favored over erythromycin because of the declining effectiveness of erythromycin, which is likely associated with emerging resistance of Cutibacterium acnes (previously called Propionibacterium acnes) 34. To reduce the risk of resistance, use of topical antibiotics as monotherapy or maintenance therapy is not recommended, and the duration of therapy should be limited to 12 weeks 35, 34.

Erythromycin and clindamycin are available in combination with benzoyl peroxide, and clindamycin is available in combination with retinoids. Use of combination agents is recommended to reduce the risk of resistance (benzoyl peroxide) and to enhance effectiveness (retinoids, benzoyl peroxide) 1. Topical antibiotics may have mild side effects, including burning, redness and itch, mainly when used in combination with benzoyl peroxide and retinoids. A rare serious adverse effect is Clostridium difficile colitis (clindamycin and erythromycin) 1.

Retinoids