Contents

Androgen insensitivity syndrome

Androgen insensitivity syndrome is a genetic condition that affects a child’s sexual development before birth and during puberty. People with androgen insensitivity syndrome are genetically male (they carry both an X and a Y chromosome), but are born with all or some of the physical traits of a female. This happens because a mutation on the X chromosome causes their body to resist androgen (male sex hormone), the hormones that produce a male appearance, they may have mostly female external sex characteristics or signs of both male and female sexual development.

There are two categories of androgen insensitivity syndrome: complete and partial androgen insensitivity syndrome:

- In complete androgen insensitivity syndrome, the body does not respond to androgen at all. Complete androgen insensitivity syndrome occurs when the body cannot use androgens at all. Complete androgen insensitivity syndrome occurs in as many as 2 to 5 per 100,000 births. People with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome have the external sex characteristics of females, but do not have a uterus and therefore do not menstruate and are unable to conceive a child (infertile). They are typically raised as females and have a female gender identity. Affected individuals have male internal sex organs (testes) that are undescended, which means they are abnormally located in the pelvis or abdomen. Undescended testes have a small chance of becoming cancerous later in life if they are not surgically removed. People with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome also have sparse or absent hair in the pubic area and under the arms.

- In partial androgen insensitivity syndrome also called Reifenstein syndrome, the body responds partially to androgen. Partial androgen insensitivity syndrome occurs at about the same rate as complete androgen insensitivity syndrome. Mild androgen insensitivity is much less common. The partial and mild forms of androgen insensitivity syndrome result when the body’s tissues are partially sensitive to the effects of androgens. People with partial androgen insensitivity can have genitalia that look typically female, genitalia that have both male and female characteristics, or genitalia that look typically male. They may be raised as males or as females and may have a male or a female gender identity. People with mild androgen insensitivity are born with male sex characteristics, but they are often infertile and tend to experience breast enlargement at puberty.

Mutations in the AR gene cause androgen insensitivity syndrome. Androgen insensitivity syndrome is an inherited condition passed down by the mother (X-linked inheritance pattern). About two-thirds of all cases of androgen insensitivity syndrome are inherited from mothers who carry an altered copy of the AR gene on one of their two X chromosomes. The remaining cases result from a new mutation that can occur in the mother’s egg cell before the child is conceived or during early fetal development. A baby’s sex is determined at the moment of conception when the mother contributes an X chromosome and the father contributes either an X or a Y chromosome. Testosterone signals an XY fetus to develop male sex organs. In androgen insensitivity syndrome, a defect on the X chromosome fully or partially blocks testosterone’s effect on the body. This prevents the fetus from responding to the male hormone, interfering with the development of the sex organs.

To prevent testicular malignancy, treatment of complete androgen insensitivity syndrome may include either removal of the testes after puberty when feminization is complete or prepubertal gonadectomy accompanied by estrogen replacement therapy. Because the risk of malignancy is low, however, removal of gonads is increasingly controversial. Additional treatment for complete androgen insensitivity syndrome may include vaginal dilatation to avoid dyspareunia. Treatment of partial androgen insensitivity syndrome in individuals with predominantly female genitalia is similar to treatment of complete androgen insensitivity syndrome, but is more likely to include prepubertal gonadectomy to help avoid increasing clitoromegaly at the time of puberty. In individuals with partial androgen insensitivity syndrome and ambiguous or predominantly male genitalia, the tendency has been for parents and health care professionals to assign sex of rearing after an expert evaluation has been completed. Those individuals with partial androgen insensitivity syndrome who are raised as males may undergo urologic surgery such as orchiopexy and hypospadias repair. Those individuals with partial androgen insensitivity syndrome who are raised as females and who undergo gonadectomy after puberty may need combined estrogen and androgen replacement therapy. Males with mild androgen insensitivity syndrome may require mammoplasty for gynecomastia. A trial of androgen pharmacotherapy may help improve virilization in infancy. It is best if the diagnosis of AIS is explained to the affected individual and family in an empathic environment, with both professional and family support.

How does androgen insensitivity syndrome affect gender identity?

There are three broad phenotypes of androgen insensitivity syndrome 1:

- Complete androgen insensitivity syndrome occurs when the body cannot respond at all to certain male sex hormones (called androgens). People with this form of the condition have female sex characteristics, but do not have a uterus. Without a uterus, they do not menstruate and are unable to carry a pregnancy or have their own biological child (infertile). They are typically raised as females and have a female gender identity 2.

- Partial androgen insensitivity syndrome occurs when the body is able to partially respond to androgens. People with partial androgen insensitivity (also called Reifenstein syndrome) can have normal female sex characteristics, both male and female sex characteristics, or normal male sex characteristics. They may be raised as males or as females, and may have a male or a female gender identity 2.

- Mild androgen insensitivity syndrome (MAIS) with typical male external genitalia.

Androgen insensitivity syndrome causes

Mutations in the AR gene and is inherited in an X-linked manner (passed down by the mother) cause androgen insensitivity syndrome. The AR gene provides instructions for making a protein called an androgen receptor. Androgen receptors allow cells to respond to androgens, which are hormones (such as testosterone) that direct male sexual development. Androgens and androgen receptors also have other important functions in both males and females, such as regulating hair growth and sex drive. Mutations in the AR gene prevent androgen receptors from working properly, which makes cells less responsive to androgens or prevents cells from using these hormones at all. Depending on the level of androgen insensitivity, an affected person’s sex characteristics can vary from mostly female to mostly male.

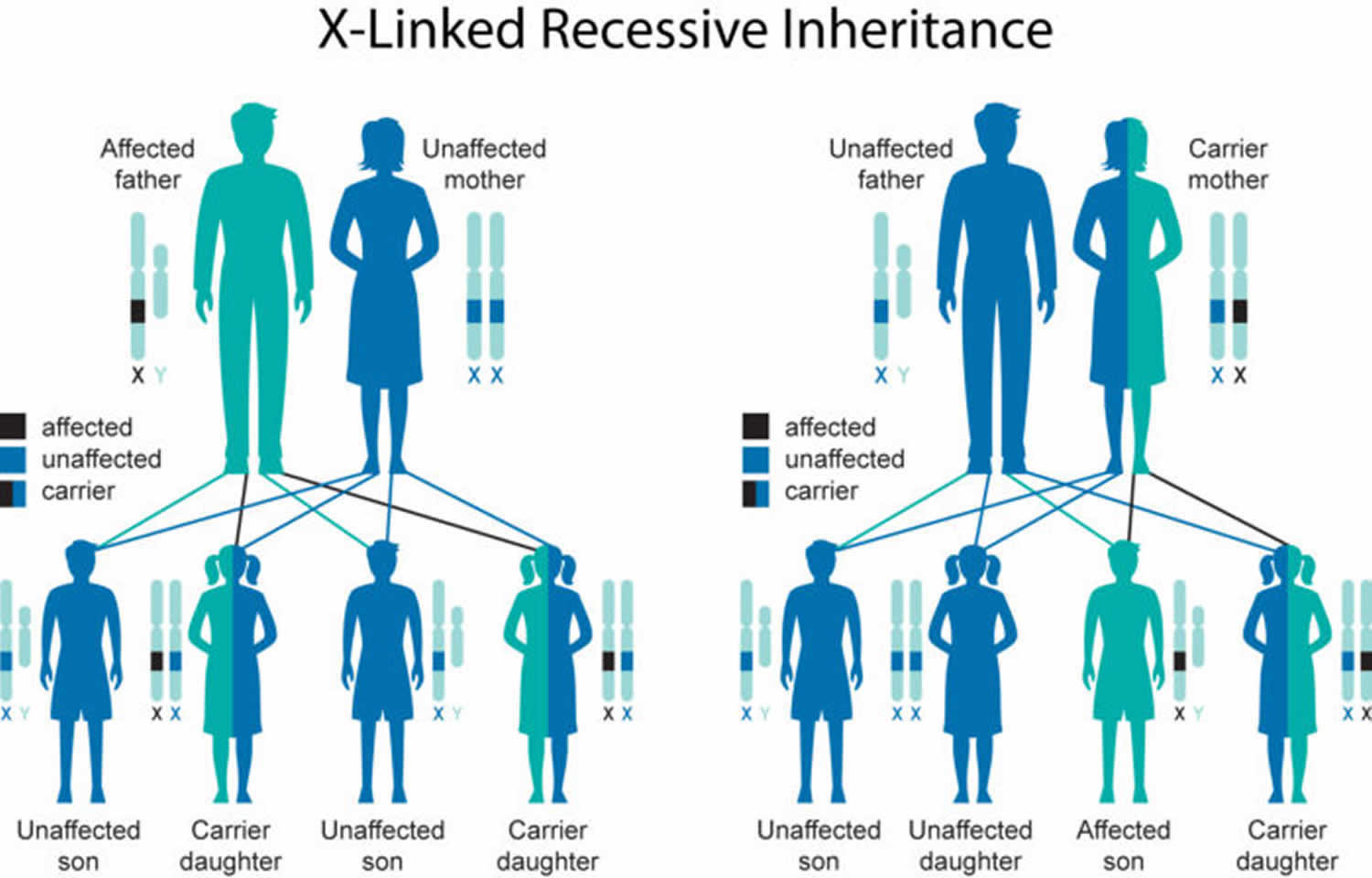

Androgen insensitivity syndrome inheritance pattern

Androgen insensitivity syndrome is inherited in an X-linked recessive pattern (passed down by the mother). A condition is considered X-linked if the mutated gene that causes the disorder is located on the X chromosome, one of the two sex chromosomes in each cell. In genetic males (who have only one X chromosome), one altered copy of the gene in each cell is sufficient to cause the condition. In genetic females (who have two X chromosomes), a mutation must be present in both copies of the gene to cause the disorder. Males are affected by X-linked recessive disorders much more frequently than females.

About two-thirds of all cases of androgen insensitivity syndrome are inherited from mothers who carry an altered copy of the AR gene on one of their two X chromosomes. The remaining cases result from a new mutation that can occur in the mother’s egg cell before the child is conceived or during early fetal development.

Figure 1. Androgen insensitivity syndrome X-linked inheritance pattern

People with specific questions about genetic risks or genetic testing for themselves or family members should speak with a genetics professional.

Resources for locating a genetics professional in your community are available online:

- The National Society of Genetic Counselors (https://www.findageneticcounselor.com/) offers a searchable directory of genetic counselors in the United States and Canada. You can search by location, name, area of practice/specialization, and/or ZIP Code.

- The American Board of Genetic Counseling (https://www.abgc.net/about-genetic-counseling/find-a-certified-counselor/) provides a searchable directory of certified genetic counselors worldwide. You can search by practice area, name, organization, or location.

- The Canadian Association of Genetic Counselors (https://www.cagc-accg.ca/index.php?page=225) has a searchable directory of genetic counselors in Canada. You can search by name, distance from an address, province, or services.

- The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (http://www.acmg.net/ACMG/Genetic_Services_Directory_Search.aspx) has a searchable database of medical genetics clinic services in the United States.

Androgen insensitivity syndrome symptoms

Infants with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome appear to be female at birth, the penis and other male body parts fail to develop, but do not have a uterus, fallopian tubes or ovaries. Their testicles are hidden inside the pelvis or abdomen. At birth, the child looks like a girl. Breasts develop during puberty, but there is little or no pubic and armpit hair. Babies born with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome are typically raised as girls and have a female gender identity. In many cases, they aren’t diagnosed until adolescence or later, when they fail to menstruate or are unable to get pregnant.

Babies born with partial androgen insensitivity syndrome may have sexual characteristics that are typical of a male, a female, or both. They may have a partial closing of the outer vagina but no cervix or uterus, an enlarged clitoris and a short vagina. There may be inguinal hernia with testes that can be felt during a physical exam and normal female breasts. They may be raised as males or as females and have a male or female gender identity.

Partial androgen insensitivity syndrome can include other disorders, such as:

- Failure of one or both testes to descend into the scrotum after birth. Testes in the abdomen or other atypical places in the body

- Hypospadias, a condition in which the opening of the urethra is on the underside of the penis, instead of at the tip

- Reifenstein syndrome (also known as Gilbert-Dreyfus syndrome or Lubs syndrome)

In the least severe cases, the only sign of androgen insensitivity syndrome is male infertility.

Infertile male syndrome is also considered to be part of partial androgen insensitivity syndrome.

Partial androgen insensitivity syndrome signs and symptoms

Characteristics of partial androgen sensitivity syndrome vary from person. Each person with partial androgen insensitivity syndrome is unique and may not have the same features.

Some people with partial androgen insensitivity syndrome may have more female-appearing features. For example, some can be born with female-appearing genitals but may have an enlarged clitoris (clitoromegaly) or fusion of certain areas of the labia. In addition, some individuals may be born with openings of a female-appearing urethra (duct where urine is released from the bladder to outside the body) and vagina. However, individuals with partial androgen insensitivity syndrome do not have female sex organs such as a uterus and ovaries. Some people with this condition may have undescended testes, in which one or both testicles are not able to descend completely by puberty. Because they do not have ovaries and may have issues with the development of the testes, many people with partial androgen insensitivity syndrome are infertile, because they produce no or very little sperm. Also, some individuals with partial androgen insensitivity syndrome may develop breasts (gynecomastia) during puberty.

Other people with partial androgen insensitivity syndrome may have more male-appearing features. For example, some may develop a penis. Some affected males may be born with a small penis, which is usually less than 1 cm, and may look similar to a clitoris. Those who develop a penis may be born with a feature called hypospadias, in which the opening of the penis is on the underside. As a result, boys with hypospadias may have issues urinating in certain directions. During puberty, people with partial androgen insensitivity syndrome may also develop a bifid scrotum, in which their scrotum area may separated by a groove into two parts.

Mild androgen insensitivity syndrome signs and symptoms

Mild androgen insensitivity syndrome (undervirilized male syndrome). The external genitalia of affected individuals are unambiguously male. They usually present with gynecomastia at puberty. They may have undermasculinization that includes sparse facial and body hair and small penis. Impotence may be a complaint. Spermatogenesis may or may not be impaired. In some instances, the only observed abnormality appears to be male infertility 3; therefore, mild androgen insensitivity syndrome could explain some cases of idiopathic male infertility 4.

Mild androgen insensitivity syndrome (undervirilized male syndrome) almost always runs true in families.

Androgen insensitivity syndrome diagnosis

No formal diagnostic criteria for identifying androgen insensitivity syndrome have as yet been published; large variance is seen at the molecular, biochemical, and morphologic levels due to the extreme variation in these characteristics with the various androgen insensitivity syndrome phenotypes 5.

Complete androgen insensitivity syndrome is rarely discovered during childhood when a testicle is felt as a mass in the groin or abdomen. Sometimes, a growth is felt in the abdomen or groin that turns out to be a testicle when it is explored with surgery. Most people with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome are not diagnosed until they do not get a menstrual period or they have trouble getting pregnant.

Partial androgen insensitivity syndrome is often discovered during childhood because the person may have both male and female physical traits.

Tests used to diagnose androgen insensitivity syndrome may include:

- Blood work to check levels of testosterone, luteinizing hormone (LH), and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)

- Genetic testing (karyotype) to determine the person’s genetic makeup

- Pelvic ultrasound

Other blood tests may be done to help tell the difference between androgen insensitivity syndrome and androgen deficiency.

Suggestive findings

Androgen insensitivity syndrome should be suspected in an individual with the following clinical, family history, radiologic, and supportive laboratory findings.

Clinical features:

- Absence of extragenital abnormalities

- Two nondysplastic testes

- Absent or rudimentary müllerian structures (i.e., fallopian tubes, uterus, and cervix) and the presence of a short vagina

- Undermasculinization of the external genitalia at birth

- Impaired spermatogenesis and/or somatic virilization (some degree of impaired virilization at puberty)

Family history of other affected individuals related to each other in a pattern consistent with X-linked inheritance. “Other affected family members” refers to:

- Affected 46,XY individuals;

- Manifesting heterozygous females (46,XX). About 10% of heterozygous females have asymmetric distribution and sparse or delayed growth of pubic and/or axillary hair.

Note: Absence of a family history of androgen insensitivity syndrome or suggestive features of androgen insensitivity syndrome does not preclude the diagnosis.

Radiology findings in the “predominantly male” phenotype including impaired development of the prostate and of the wolffian duct derivatives demonstrated by ultrasonography or genitourography.

Supportive laboratory findings:

- Normal 46,XY karyotype

- Evidence of normal or increased synthesis of testosterone (T) by the testes

- Evidence of normal conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone (DHT)

- Evidence of normal or increased luteinizing hormone (LH) production by the pituitary gland

- In complete androgen insensitivity syndrome, but not in partial androgen insensitivity syndrome: possible reduction in postnatal (0-3 months) surge in serum LH and serum T concentrations 6

- In the “predominantly male” phenotype:

- Less than normal decline of sex hormone-binding globulin in response to a standard dose of the anabolic androgen, stanozolol 7

- Higher than normal levels of anti-müllerian hormone during the first year of life or after puberty has begun

Establishing the diagnosis

The diagnosis of androgen insensitivity syndrome is established in a 46,XY proband with:

- Undermasculinization of the external genitalia, impaired spermatogenesis with otherwise normal testes, absent or rudimentary müllerian structures, evidence of normal or increased synthesis of testosterone and its normal conversion to dihydrotestosterone, and normal or increased LH production by the pituitary gland; AND/OR

- A hemizygous pathogenic variant in AR gene identified by molecular genetic testing.

Molecular genetic testing approaches can include single-gene testing, use of a multigene panel, and more comprehensive genomic testing.

- Single-gene testing. Sequence analysis of AR gene is performed first. Gene targeted deletion/duplication analysis to detect multiexon or whole-gene deletions or duplications may be considered if a pathogenic variant in AR is not identified by sequence analysis.

- A multigene panel that includes AR and other genes of interest may also be considered. Note: (1) The genes included in the panel and the diagnostic sensitivity of the testing used for each gene vary by laboratory and are likely to change over time. (2) Some multigene panels may include genes not associated with androgen insensitivity syndrome; thus, clinicians need to determine which multigene panel is most likely to identify the genetic cause of the condition at the most reasonable cost while limiting identification of variants of uncertain significance and pathogenic variants in genes that do not explain the underlying phenotype. (3) In some laboratories, panel options may include a custom laboratory-designed panel and/or custom phenotype-focused exome analysis that includes genes specified by the clinician. (4) Methods used in a panel may include sequence analysis, deletion/duplication analysis, and/or other non-sequencing-based tests.

- More comprehensive genomic testing (when available) including exome sequencing and genome sequencing may be considered if single-gene testing (and/or use of a multigene panel that includes AR) fails to confirm a diagnosis in an individual with features of androgen insensitivity syndrome. Such testing may provide or suggest a diagnosis not previously considered (e.g., mutation of a different gene or genes that results in a similar clinical presentation).

Androgen insensitivity syndrome treatment

Complete androgen insensitivity syndrome is treated with estrogen replacement therapy after puberty. Testicles that are in the wrong place may not be removed until a child finishes growing and goes through puberty. At this time, the testes may be removed because they can develop cancer, just like any undescended testicle.

Treatment for partial androgen insensitivity syndrome may include corrective surgery to match gender identity. If your child identifies as male, hormone therapy will include testosterone.

Treatment and gender assignment can be a very complex issue, and must be targeted to each individual person.

Ongoing psychological support is an important part of treatment. Parents of a newly diagnosed child may benefit from counseling as well.

Prevention of secondary manifestations

Regular weight-bearing exercises and supplemental calcium and vitamin D are recommended to optimize bone health; bisphosphonate therapy may be indicated for those with evidence of decreased bone mineral density and/or multiple fractures.

Surveillance

Periodic reevaluation for gynecomastia during puberty in individuals assigned a male sex; monitoring of bone mineral density through DEXA scanning in adults.

Androgen insensitivity syndrome prognosis

The outlook for complete androgen insensitivity syndrome is good if the testicle tissue is removed at the right time. The outlook for partial androgen insensitivity syndrome depends on the appearance of the genitals.

Children with androgen insensitivity syndrome will become infertile as adults. However, with psychological support and hormone replacement therapy, they are able to otherwise lead a normal life.

Possible complications include:

- Infertility

- Psychological and social issues

- Testicular cancer.

- Gottlieb B, Trifiro MA. Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome. 1999 Mar 24 [Updated 2017 May 11]. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al., editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2020. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1429[↩]

- Androgen insensitivity syndrome. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/androgen-insensitivity-syndrome[↩][↩]

- Gottlieb B, Lumbroso R, Beitel LK, Trifiro MA. Molecular pathology of the androgen receptor in male (in)fertility. Reprod Biomed Online. 2005;10:42–8.[↩]

- Goglia U, Vinanzi C, Zuccarello D, Malpassi D, Ameri P, Casu M, Minuto F, Fioresta C, Ferone D. Identification of a novel mutation in exon 1 of the androgen receptor gene in an azoospermic patient with mild androgen insensitivity syndrome: case report and literature review. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:1165–9.[↩]

- Gottlieb B, Beitel LK, Nadarajah A, Paliouras M, Trifiro M. The androgen receptor gene mutations database (ARDB): 2012 update. Hum Mutat. 2012;33:887–94.[↩]

- Bouvattier C, Carel JC, Lecointre C, David A, Sultan C, Bertrand AM, Morel Y, Chaussain JL. Postnatal changes of T, LH, and FSH in 46,XY infants with mutations in the AR gene. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:29–32.[↩]

- Sinnecker GH, Hiort O, Nitsche EM, Holterhus PM, Kruse K. Functional assessment and clinical classification of androgen sensitivity in patients with mutations of the androgen receptor gene. German Collaborative Intersex Study Group. Eur J Pediatr. 1997;156:7–14.[↩]