Contents

Congenital rubella syndrome

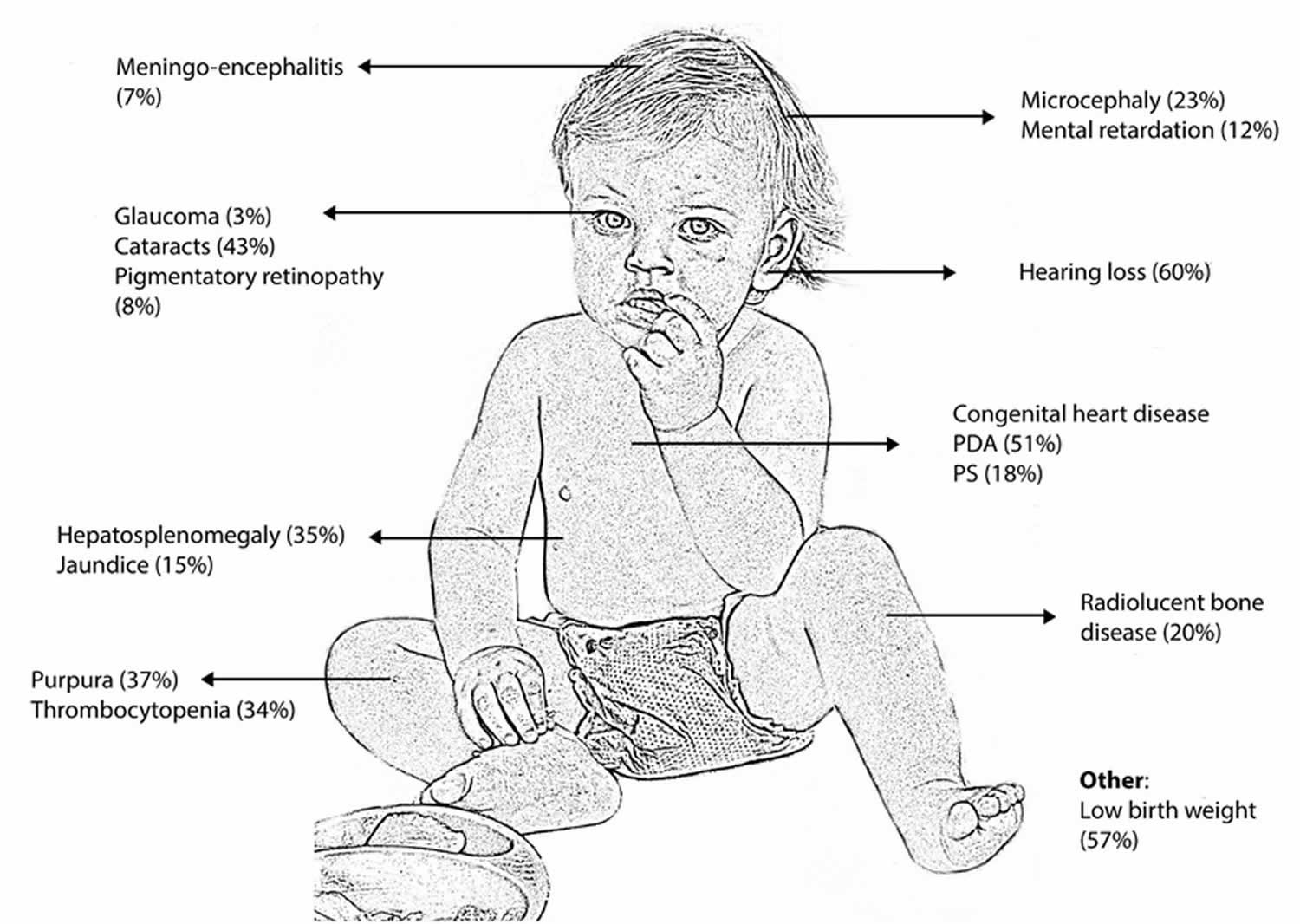

Congenital rubella syndrome is a rare fetal malformation syndrome (group of birth defects) with lifelong consequences that occur in an infant whose mother is infected with the Rubella virus that causes rubella (German measles) during the first trimester of pregnancy. Congenital rubella syndrome occurs when the rubella virus in the mother affects the developing baby in the first 3 months of pregnancy. After the fourth month, if the mother has a rubella infection, it is less likely to harm the developing baby 1. Congenital means the condition is present at birth. Classically congenital rubella syndrome leads to the triad of deafness (80%), congenital cardiac disease (50- 70%, most commonly patent ductus arteriosus or pulmonary stenosis) and cataracts (30%), but many other defects involving almost every organ have been described (Figure 1) 2. The most common problems in congenital rubella syndrome are hearing loss due to damage to the nerve pathways from the inner ear to the brain (sensorineural hearing loss), ocular abnormalities (cataract, infantile glaucoma, and pigmentary retinopathy) and heart problems. Other symptoms and signs may include intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR), prematurity, stillbirth, miscarriage, neurological problems (intellectual disability, low muscle tone, very small head), liver and spleen enlargement (hepatosplenomegaly), jaundice, skin problems, anemia, hormonal problems, and other issues 3.

Congenital rubella syndrome risk is highest if the mother is infected in the first trimester of her pregnancy. Infection during this time carries a risk of congenital rubella syndrome that can be as high as 90%, although spontaneous miscarriage is common 4. Sensorineural deafness can occur with infection right up to the 19th week of gestation and may only become evident later in childhood 5. More severe complications include acute meningo-encephalitis (10 – 20%) and late onset progressive panencephalitis. The risk of intellectual disability, behavioral problems and autism are all increased in children with congenital rubella syndrome. Studies have shown that affected adults also have an increased risk of developing endocrinopathies such as diabetes mellitus and thyroid problems 2. Although congenital rubella syndrome is a disease with a variable spectrum of clinical presentation and outcome, many patients require lifelong care.

There is no cure for congenital rubella syndrome. So, it is important to get vaccinated before you get pregnant.

Support of an infant born with congenital rubella syndrome varies depending on the extent of the infant’s problems. Children who have multiple complications may require early treatment from a team of specialists.

Congenital rubella syndrome has no cure, but it is almost completely preventable by an effective MMR (measles, mumps and rubella vaccine) immunization program. The number of babies born with congenital rubella is much less since the rubella vaccine was developed. Pregnant women who are not vaccinated for rubella and who have not had the disease in the past risk infecting themselves and their unborn baby. One dose of the MMR vaccine is about 97% effective at preventing rubella 6. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends children get two doses of MMR vaccine, starting with the first dose at 12 through 15 months of age, and the second dose at 4 through 6 years of age. Teens and adults also should also be up to date on their MMR vaccination. MMR vaccine is a live attenuated vaccine, and due to its theoretical teratogenic risk, women who are pregnant and not vaccinated should wait to get MMR until after they have given birth 7. Pregnant women should wait to get MMR vaccine until after they are no longer pregnant. Women should avoid getting pregnant for at least 1 month after getting MMR vaccine. Although, several publications have reported the absence of congenital rubella syndrome after vaccination during pregnancy.

Congenital rubella syndrome is a global public health concern with more than 100,000 cases reported annually worldwide 8. Natural rubella infection during pregnancy is one of the few known causes of autism. As many as 8%–13% of children with congenital rubella syndrome developed autism during the rubella epidemic of the 1960s compared to the background rate of about 1 new case per 5000 children 9.

Before the availability of rubella vaccines in the United States in 1969, rubella was a common disease that occurred primarily among young children. The last major epidemic in the United States occurred during 1964 to 1965, when there was an estimated 12.5 million rubella cases in the United States. Because of successful vaccination programs, rubella has been eliminated from the United States since 2004. Since elimination, fewer than 10 congenital rubella syndrome cases have been reported annually in the United States, and most cases were imported from outside the country 10. Unvaccinated people can get rubella while abroad and bring the disease to the United States and spread it to others.

Rubella continues to be a commonly transmitted infection in many parts of the world. Many rubella cases are not recognized, as the rash resembles many other illnesses and up to half of all infections may be subclinical.

Humans are the only source of rubella infection. Transmission is through direct or droplet contact from nasopharyngeal secretions. Once inhaled, the virus replicates in the respiratory mucosa and cervical lymph nodes before reaching the target organs via systemic circulation. The infectious period extends approximately 8 days before to 8 days after the rash onset 11.

Maternal rubella during pregnancy can cause miscarriage, fetal death or congenital rubella syndrome 11. Few infants with congenital rubella continue to spread the virus in nasopharyngeal secretions and urine for a year or more. Rubella virus also has been recovered from lens aspirates in children with congenital cataracts for several years.

Figure 1. Congenital rubella syndrome

Footnote: Common clinical manifestations of congenital rubella syndrome.

[Source 12 ]Figure 2. Congenital rubella (eye cataracts)

Footnote: Eye cataracts (arrows) in case-patient with congenital rubella syndrome.

Congenital rubella syndrome causes

Congenital rubella occurs when the rubella virus in the mother affects the developing baby in the first 3 months of pregnancy. After the fourth month, if the mother has a rubella infection, it is less likely to harm the developing baby.

The number of babies born with congenital rubella is much smaller since the rubella vaccine was developed.

Pregnant women and their unborn babies are at risk if:

- They are not vaccinated for rubella

- They have not had the disease in the past.

Most people who get rubella usually have mild illness, with symptoms that can include a low-grade fever, sore throat, and a rash that starts on the face and spreads to the rest of the body. Some people may also have a headache, pink eye, and general discomfort before the rash appears. Rubella can cause a miscarriage or serious birth defects in an unborn baby if a woman is infected while she is pregnant.

- Congenital rubella infection – Congenital rubella infection encompasses all outcomes associated with intrauterine rubella infection (eg, miscarriage, stillbirth, combinations of birth defects, asymptomatic infection) 13.

- Congenital rubella syndrome – Congenital rubella syndrome refers to variable constellations of birth defects (eg, hearing impairment, congenital heart defects, cataracts/congenital glaucoma, pigmentary retinopathy, etc)

The pathogenesis of congenital rubella syndrome is multifactorial and not well understood 14, 15.

- Non-inflammatory necrosis in the epithelium of the chorion and in the endothelial cells is observed. These cells are transported to the fetal circulation and fetal organs such as eyes, heart, brain and ears, prompting thrombosis and ischemic lesions.

- Actin assembly is inhibited directly or indirectly in rubella infection, leading to the inhibition of cell mitosis and development of organ precursor cells.

- The immune system might play a role because interferon and cytokines appear to be upregulated in rubella-infected human fetal cells, which could disrupt developing and differentiating cells and thus contribute to congenital defects 16.

In children with congenital rubella syndrome, the rubella virus persists and is detected in urine, saliva and cerebrospinal fluid for several months 17, which could be explained by a defect in cell-mediated immunity 18. T-cell abnormalities have been observed in young adults with congenital rubella syndrome, possibly leading to organ-specific autoimmunity disorders 19.

Congenital rubella syndrome symptoms

Few or no obvious clinical manifestations occur at birth with mild forms of the disease. The incidence of congenital infection with rubella is high during the early and late weeks of gestation (U-shaped distribution), with chances of birth defects much higher if the infection occurs early in pregnancy.

Congenital defects occur in up to 85% of neonates if maternal infection occurs during the first 12 weeks of gestation, in 50% of neonates if infection occurs during the first 13 to 16 weeks of gestation, and 25% if infection occurs during the latter half of the second trimester.

Congenital rubella syndrome include the following 20:

- Congenital heart defects (patent ductus arteriosus, peripheral pulmonary artery stenosis, ventricular septal defects, atrial septal defects)

- Auditory (sensorineural hearing impairment)

- Ophthalmologic (cataracts, pigmentary retinopathy, microphthalmos, chorioretinitis)

- Neurologic (microcephaly, cerebral calcifications, meningoencephalitis, behavioral disorders, mental retardation)

- Hematologic (thrombocytopenia, hemolytic anemia, petechiae/purpura, dermal erythropoiesis causing “blueberry muffin” rash)

- Neonatal manifestations (low birth weight, interstitial pneumonitis, radiolucent bone disease leading to “celery stalking” of long bone metaphyses, hepatosplenomegaly)

- Delayed onset of insulin-dependent diabetes and thyroid disease.

Symptoms in infant with congenital rubella syndrome may include:

- Cloudy corneas or white appearance of pupil (cataracts)

- Deafness

- Developmental delay

- Excessive sleepiness

- Irritability

- Low birth weight

- Below average mental functioning (intellectual disability)

- Seizures

- Small head size

- Liver and spleen damage

- Skin rash at birth

- Glaucoma

- Brain damage

- Thyroid and other hormone problems

- Inflammation of the lungs.

Congenital rubella syndrome diagnosis

Maternal screening with rubella titers in early pregnancy is considered standard of care in the United States 8. Rubella-like illness in early pregnancy should be evaluated to confirm the diagnosis. Laboratory diagnosis is based on observation of seroconversion with use of rubella-specific-IgG and IgM antibody in the cord blood or in the neonatal serum collected within the first 6 months of life 21, 22. In infants older than 3 months, a negative rubella-specific IgM does not exclude a congenital rubella infection although a positive test does support the diagnosis 23. Congenital rubella infection can also be confirmed by demonstrating persistent or increasing serum concentrations of rubella-specific IgG over the first 7 to 11 months of life 21. Detection of rubella virus RNA by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) in nasopharyngeal swab or urine provides laboratory evidence of congenital rubella syndrome.

Prenatal fetal diagnosis is based on detection of viral genome in amniotic fluid, fetal blood or chorionic villus biopsies.

Postnatal diagnosis of congenital rubella infection is done by detecting rubella virus-IgG antibodies in neonatal serum using ELISA. This approach has sensitivity and specificity of nearly 100% in infants less than three months of age. Confirmation of infection is made by detection of rubella virus in nasopharyngeal swabs, urine and oral fluid using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) 11.

Congenital infection can also be confirmed by stable or increasing serum concentrations of rubella-specific IgG over the first year of life. Maternal counseling and termination of pregnancy are options in such cases. It is difficult to diagnose congenital rubella in children older than one year of age.

Postnatal confirmation of congenital infection is important despite the absence of clinical features of congenital rubella syndrome. This is to develop a specific follow-up care plan for early detection of long-term neurological and ocular complications 24.

Prenatal diagnosis of congenital infection

A prenatal diagnosis of congenital infection is recommended when a maternal infection is diagnosed and is based on the detection of rubella-specific-IgM in fetal blood or on the detection of the viral genome in amniotic fluid, fetal blood or chorionic villus biopsies 17, 25. The detection of rubella virus in chorionic villus biopsies reflects an infection of the villi, not a fetal infection.

The specificity of a prenatal diagnosis is approximately 100%, and the sensitivity is greater than 90% if the following conditions are met 25:

- At least a 6-week period passes between the infection and sampling;

- A sample collection is performed after 21 weeks gestation; and

- The samples for reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) are stored and transported frozen (fetal blood for rubella virus-IgM detection is stored and transported at 4 °C).

Postnatal diagnosis of congenital infection

A postnatal diagnosis of congenital infection is based on the detection of a specific rubella virus-IgM by immunocapture ELISA, which has sensitivity and specificity that approach 100% in infected newborns (<3 months of age) 26. In cases in which the rubella virus-IgM test is positive, a congenital infection might be confirmed by isolating the rubella virus or by detecting the viral genome in nasopharyngeal swabs, urine and oral fluid using reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) 27.

Performing a postnatal diagnosis of a congenital infection is important, regardless of whether a clinical manifestation of congenital rubella syndrome is observed, to provide a specific follow-up care plan if an infection is discovered (including neurological and hearing monitoring) 17.

A child infected in utero could excrete the virus in saliva and urine for several months or years.

Congenital rubella syndrome treatment

Although symptoms associated with congenital rubella syndrome can be treated, there is no cure for the congenital rubella syndrome; hence, prevention should be the goal. There is no treatment is available for congenital rubella syndrome, it is important for women to get vaccinated before they get pregnant.

Congenital rubella syndrome is a chronic disease, and these children need to be followed up to detect progression and the emergence of new problems. A multidisciplinary team approach is required, involving pediatric, ophthalmologic, cardiac, audiological, neurodevelopmental evaluation, educational and rehabilitative management. Long-term follow up is needed to monitor for delayed manifestations 15.

Prenatal management of the mother and fetus depends on gestational age at onset of infection. If infection happens before 18 weeks gestation, the fetus is at high risk for infection and severe symptoms. Termination of pregnancy could be discussed based on local legislation. Detailed ultrasound examination and assessment of viral RNA in amniotic fluid is recommended.

For infections after 18 weeks of gestation, pregnancy could be continued with ultrasound monitoring followed by neonatal physical examination and testing for rubella virus-IgG 11.

Limited data suggest a benefit of intramuscular immune globulin (Ig) for maternal rubella infection leading to decrease in viral shedding and risk of fetal infection.

Control measures

Children with congenital rubella syndrome should be considered contagious until at least one year of age unless two negative cultures are obtained one month apart after 3 months of age. Neonates should be isolated. Hand hygiene is of utmost importance for reducing disease transmission from the urine of children with congenital rubella infection 28.

- Congenital rubella. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/001658.htm[↩]

- Remington JS, Klein JO, Wilson CB, Nizet V, Maldonado YA. Infectious Diseases of the Fetus and Newborn Infant. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2011:861-898.[↩][↩]

- Pediatric Rubella Clinical Presentation. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/968523-clinical#showall[↩]

- Best JM, O’Shea S, Tipples G, et al. Interpretation of rubella serology in pregnancy – pitfalls and problems. BMJ 2002;325:147-148.[↩]

- Cooper LZ. The history and medical consequences of rubella. Reviews of Infectious Diseases 1985;7(1):S2-S10.[↩]

- Rubella (German Measles) Vaccination. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/rubella/index.html[↩]

- MMR (Measles, Mumps, & Rubella) Vaccine Information Statements. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/vis/vis-statements/mmr.html[↩]

- Shukla S, Maraqa NF. Congenital Rubella. [Updated 2019 Jun 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507879[↩][↩]

- Mawson AR, Croft AM. Rubella Virus Infection, the Congenital Rubella Syndrome, and the Link to Autism. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(19):3543. Published 2019 Sep 22. doi:10.3390/ijerph16193543 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6801530[↩]

- Al Hammoud R, Murphy JR, Pérez N. Imported Congenital Rubella Syndrome, United States, 2017. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24(4):800–801. doi:10.3201/eid2404.171540 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5875265[↩]

- Bouthry E, Picone O, Hamdi G, Grangeot-Keros L, Ayoubi JM, Vauloup-Fellous C. Rubella and pregnancy: diagnosis, management and outcomes. Prenat. Diagn. 2014 Dec;34(13):1246-53.[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Boshoff, L & Tooke, Lloyd. (2012). Congenital rubella: Is it nearly time to take action?. South African Journal of Child Health. 6. 10.7196/sajch.461[↩]

- Reef SE, Plotkin S, Cordero JF, et al. Preparing for elimination of congenital Rubella syndrome (CRS): summary of a workshop on CRS elimination in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31(1):85–95. doi:10.1086/313928[↩]

- Lee JY, Bowden DS. Rubella virus replication and links to teratogenicity. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000 Oct;13(4):571-87. doi: 10.1128/CMR.13.4.571[↩]

- Leung AKC, Hon KL, Leong KF. Rubella (German measles) revisited. Hong Kong Med J. 2019 Apr;25(2):134-141. https://www.hkmj.org/abstracts/v25n2/134.htm[↩][↩]

- Adamo MP, Zapata M, Frey TK. Analysis of gene expression in fetal and adult cells infected with rubella virus. Virology. 2008 Jan 5;370(1):1-11. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.08.003[↩]

- Best JM, Enders G. Chapter 3 Laboratory diagnosis of rubella and congenital rubella. Perspect Med Virol 2006; 15: 39–77.[↩][↩][↩]

- Buimovici-Klein E, Lang PB, Ziring PR, Cooper LZ. Impaired cell-mediated immune response in patients with congenital rubella: correlation with gestational age at time of infection. Pediatrics. 1979 Nov;64(5):620-6.[↩]

- Rabinowe SL, George KL, Loughlin R, Soeldner JS, Eisenbarth GS. Congenital rubella. Monoclonal antibody-defined T cell abnormalities in young adults. Am J Med. 1986 Nov;81(5):779-82. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(86)90344-x[↩]

- Kaushik A, Verma S, Kumar P. Congenital rubella syndrome: A brief review of public health perspectives. Indian J Public Health. 2018 Jan-Mar;62(1):52-54.[↩]

- Kimberlin DW, Brady MT, Jackson MA, Long SS, editors. Red Book: 2018 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 31st ed. Itasca: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2018: 705-11.[↩][↩]

- Dobson SR. Congenital rubella syndrome: clinical features and diagnosis. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/congenital-rubella-syndrome-clinical-features-and-diagnosis[↩]

- Banatvala JE, Brown DW. Rubella. Lancet. 2004 Apr 3;363(9415):1127-37. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15897-2[↩]

- Vauloup-Fellous C. Standardization of rubella immunoassays. J. Clin. Virol. 2018 May;102:34-38.[↩]

- Macé M, Cointe D, Six C, Levy-Bruhl D, Parent du Châtelet I, Ingrand D, Grangeot-Keros L. Diagnostic value of reverse transcription-PCR of amniotic fluid for prenatal diagnosis of congenital rubella infection in pregnant women with confirmed primary rubella infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2004 Oct;42(10):4818-20. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.10.4818-4820.2004[↩][↩]

- Thomas HI, Morgan-Capner P, Cradock-Watson JE, Enders G, Best JM, O’Shea S. Slow maturation of IgG1 avidity and persistence of specific IgM in congenital rubella: implications for diagnosis and immunopathology. J Med Virol. 1993 Nov;41(3):196-200. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890410305[↩]

- Bosma TJ, Corbett KM, Eckstein MB, O’Shea S, Vijayalakshmi P, Banatvala JE, Morton K, Best JM. Use of PCR for prenatal and postnatal diagnosis of congenital rubella. J Clin Microbiol. 1995 Nov;33(11):2881-7. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.11.2881-2887.1995[↩]

- Obam Mekanda FM, Monamele CG, Simo Nemg FB, Sado Yousseu FB, Ndjonka D, Kfutwah AKW, Abernathy E, Demanou M. First report of the genomic characterization of rubella viruses circulating in Cameroon. J. Med. Virol. 2019 Jun;91(6):928-934.[↩]