Contents

- Diverticulosis and diverticulitis

- What is the difference between diverticulitis and diverticulosis?

- Does what I eat and drink play a role in causing or preventing diverticular disease?

- Diverticular disease symptoms

- Diverticular disease complications

- Diverticular disease causes

- Risk factors for developing diverticular disease

- Diverticular disease pathophysiology

- Diverticular disease prevention

- Diverticular disease diagnosis

- Diverticular disease treatment

- Diverticular disease complications treatment

- Diverticular disease diet

- Diverticulitis

Diverticulosis and diverticulitis

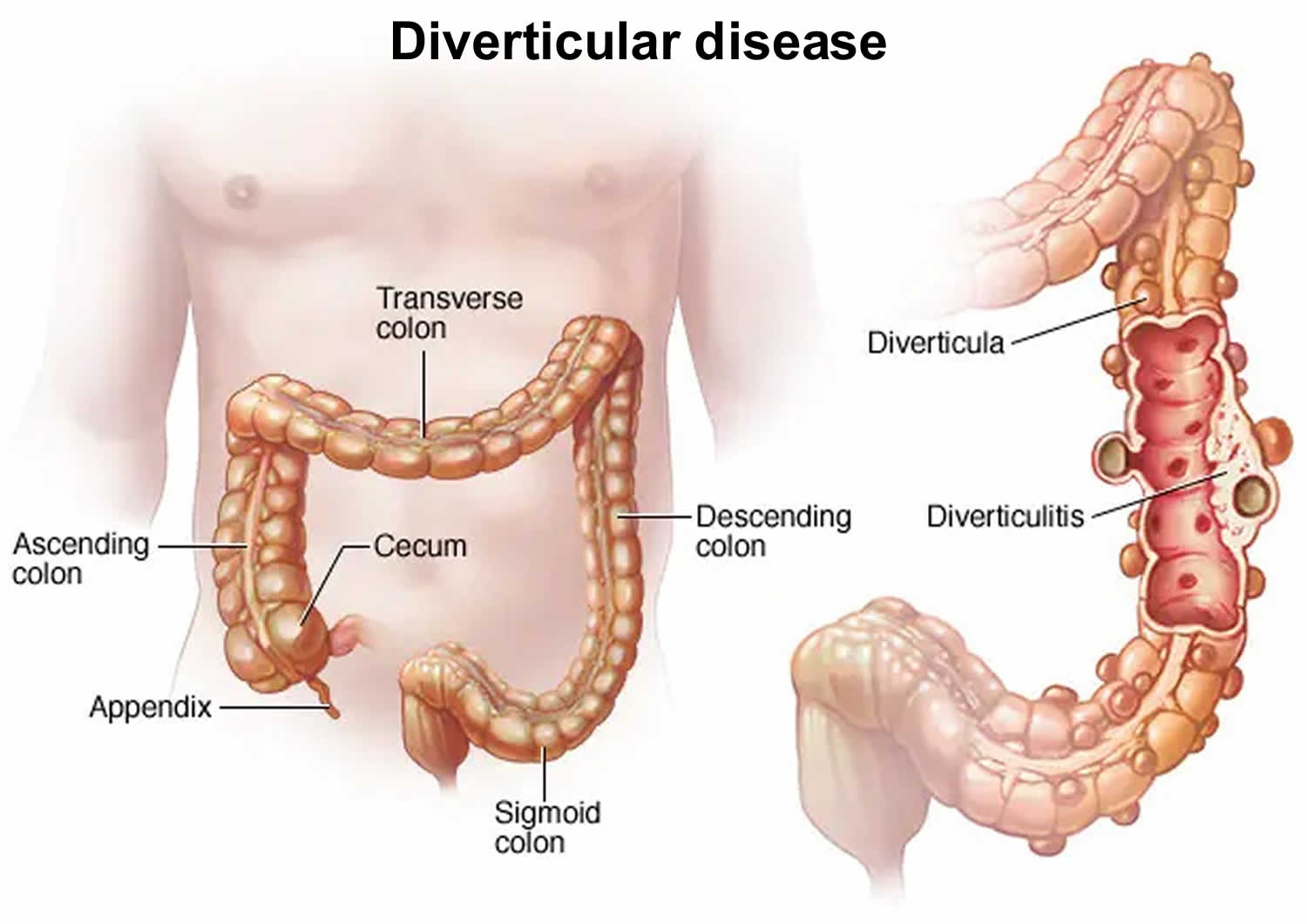

Diverticular disease is a common condition where small pouches or pockets form in the wall of your large intestine or the colon. These pouches or pockets are called diverticula and often do not cause any symptoms. Diverticula usually develop in weak areas of the intestinal muscles. This causes marble-sized pouches to protrude through the colon wall. Diverticula usually arise in the sigmoid colon 1. This S-shaped section of the large intestine is roughly 40 to 45 centimeter long and found just in front of the rectum. The contents of the intestine put the most pressure on the muscular wall here. In Western countries, diverticula are most common in the sigmoid colon with a rate of 65% 2. The right colon is more commonly involved in Asian populations 3. This difference was once attributed to daily dietary fiber, but epidemiologic studies have refuted this concept. These studies have analyzed Asian populations after relocation and change in dietary habits, but there is not yet proof of any change in the diverticular pattern 4. Although environmental factors play a significant role in diverticulosis development, studies on identical twins have identified a strong genetic predisposition 5.

The most common conditions of diverticular disease are:

- Diverticulosis. If you have these pouches in the wall of your large intestine, you have a condition called diverticulosis. It becomes more common as you age. About half of all people over age 60 have it. Most people with diverticulosis don’t know they have it and don’t have symptoms. Doctors believe the main cause is a low-fiber diet. Sometimes diverticulosis causes mild cramps, bloating or constipation. Diverticulosis is often found through tests ordered for something else. For example, it is often found during a colonoscopy to screen for cancer. A high-fiber diet and mild pain reliever will often relieve symptoms.

- Diverticulitis. If the pouches in the wall of your large intestine become inflamed or infected, you have a condition called diverticulitis. It can cause pain and other symptoms. The most common symptom of diverticulitis is abdominal pain, usually on the left side. You may also have fever, nausea, vomiting, chills, cramping, and constipation. Your doctor will do a physical exam and imaging tests to diagnose it. Treatment may include antibiotics, pain relievers, and a liquid diet. In serious cases, diverticulitis can lead to bleeding, tears, or blockages. Serious cases could require staying in the hospital or surgery.

- Diverticular bleeding. Diverticular bleeding occurs when a blood vessel in the pouch bursts. It’s not as common as diverticulitis. About 71,000 people are hospitalized for diverticular bleeding each year 6.

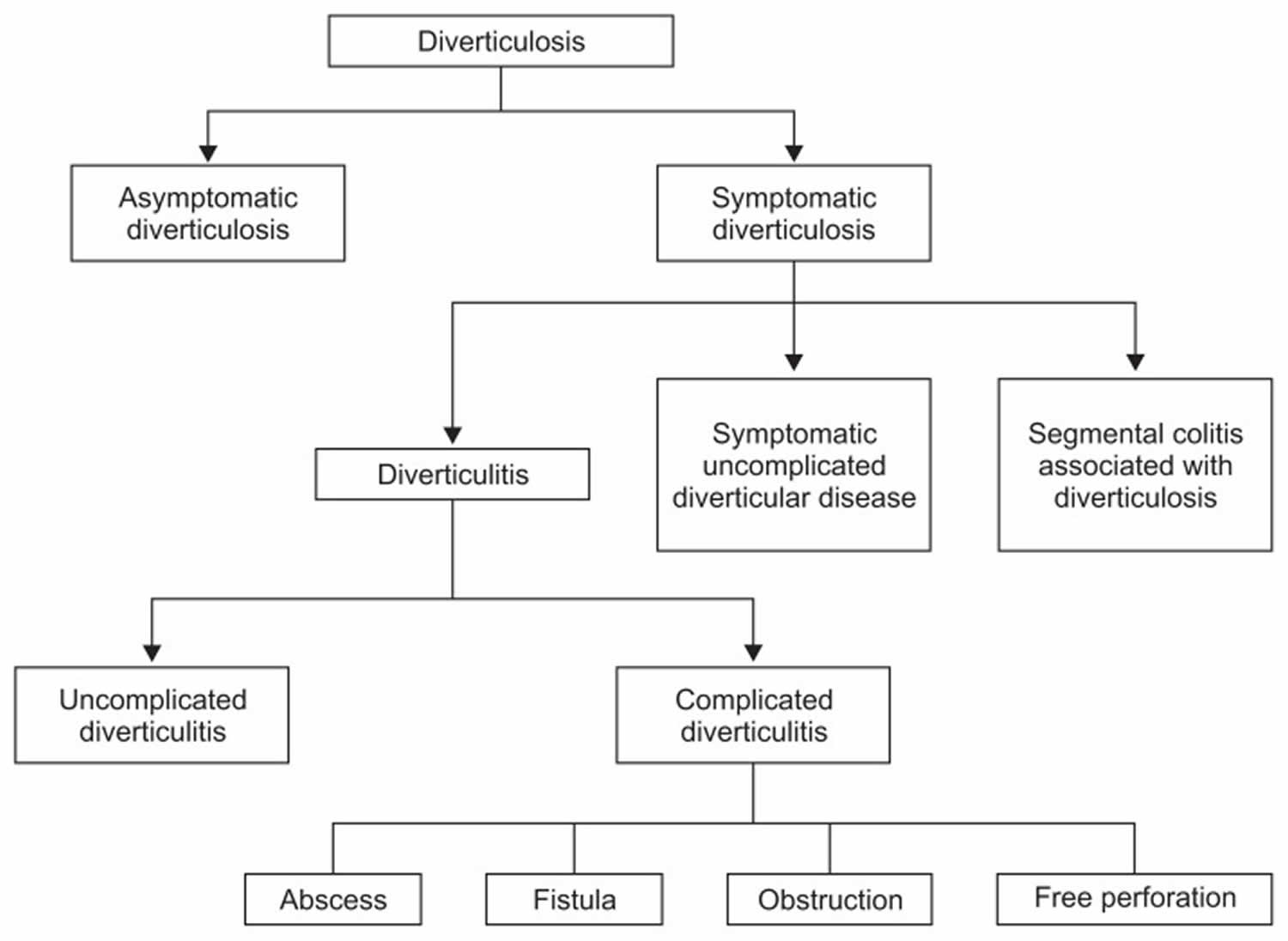

- In the recent years, there has been an evolution in the classification of symptomatic diverticular disease into several distinct types (Figure 2). These include chronic recurrent diverticulitis, segmental colitis associated with diverticulosis (SCAD) and symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease (SUDD) 7. Symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease (SUDD) is defined as chronic diverticulosis with associated chronic abdominal pain in the absence of acute symptoms of diverticulitis or overt colitis 8. There may be an overlap between symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease (SUDD) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) due to similar pathophysiologic mechanisms underlying both disease processes, which includes visceral hypersensitivity 8. This was studied by Clemens et al. 9, where they found that SUDD patient had hyperalgesia in the sigmoid colon with diverticula. SUDD is further compared to IBS in regards to altered colonic motility. Bassotti et al. 10 demonstrated that patients with diverticulosis have a reduction in the number of colonic interstitial cells of Cajal (the gut pacemaker cells) and enteric glial cells even though there was no abnormalities in the enteric neuronal population. They studied interstitial cells of Cajal (the gut pacemaker cells) due to their role in regulation of intestinal motor function and postulated that with reduction in interstitial cells of Cajal (the gut pacemaker cells), there is a decrease in colonic electrical slow wave activity which results in slowed transit. At this time, it is unclear whether symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease (SUDD) and IBS are on a continuum in terms of their pathophysiology or whether patients with IBS are more likely to have diverticulosis and therefore with chronic abdominal pain be labeled as SUDD.

- Segmental colitis associated with diverticulosis (SCAD) is now recognized as a distinct entity 11. It is characterized by nonspecific segmental inflammation in the sigmoid colon surrounded by multiple diverticula 11. It does not necessarily involve the diverticular orifice 12. Risk factors include male sex and age over 50 years 11. Initial presentation is often rectal bleeding with some presenting with diarrhea and/or abdominal pain 11. Freeman 13 studied the clinical behavior of segmental colitis associated with diverticulosis (SCAD) in over a 20-year period and noted that all patients had complete clinical and pathological remission of disease even those not treated with oral 5-aminosalicylate. Of importance, is the fact that this process appears to be benign and self-limited 11.

A 1970 study hypothesized that a diet high in fiber was protective against diverticular disease, but evidence in this regard is conflicting 14. For patients with a history of diverticulitis, The American Gastroenterology Association and the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons recommend a diet high in fiber. In this setting, increasing dietary fiber correlates with a reduction in the development of recurrent episodes of acute uncomplicated and complicated diverticulitis 15.

Red meat, particularly beef and lamb, has been associated with an increased risk of diverticulitis hospitalization. Obesity, smoking, and alcohol use are also associated with a higher incidence of diverticular disease 16. Medications, including non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), aminosalicylates (ASA), and acetaminophen, seem to increase the risk of developing complicated diverticulitis. Current corticosteroid use doubles the risk of developing perforated diverticulitis 17.

Diverticular disease is a common condition in the Western world (industrialized countries) and has significant impact on patient health as well as health care cost 5. Diverticular disease is present in around 10% of people aged less than 40 years and increases up to more than 70% in people aged more than 80 years, with prevalence being similar in both men and women 2. Approximately 130,000 hospitalizations occurring every year in the United States are attributable to diverticular disease 18. Research suggests that, in the United States, diverticulitis is more common in white Americans than in other groups, and diverticular bleeding is more common in Black Americans than in other groups 6.

Less than 5% of people with diverticulosis develop diverticulitis 19. In the United States, about 200,000 people are hospitalized for diverticulitis each year 19. An analysis of the age-adjusted hospitalization rate of diverticulitis in the United States showed an increase from 62 per 100,000 in 1998 to 76 per 100,000 in 2005 20. These admission rates increased most in younger patients (< 45 years old) and have remained unchanged in patients older than 65 years 2.

Doctors haven’t determined exactly what causes diverticular disease. They think it may be caused by not eating enough fiber. When you don’t eat enough fiber, your stools may not be soft. You can get constipated. Constipation and hard stools increase the pressure in the bowel walls. This pressure may cause the diverticular pouches to form. Eating a lot of red meat, smoking and not getting enough movement are also believed to be risk factors for developing diverticular disease.

Some people are more likely to develop diverticula because of their genes 21, 22, 23. Further risk factors include weak connective tissue and problems with the wave-like movements of the intestinal wall. Older and very overweight people are at greater risk, too.

It’s still not clear how diverticula become inflamed and what increases the risk of this happening. But inflammation is believed to be more likely in areas of reduced blood supply and if hard lumps of stool form in the diverticula.

Complications are more common in people who have a weakened immune system (for instance, after an organ transplant) or severe kidney disease. The long-term use of particular medications probably increases the risk of more serious complications. These medications include non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), steroids, acetylsalicylic acid (the drug in medicines like Aspirin) and opiates.

If you have diverticulosis, you may sometimes get flare-ups of diverticulitis. To prevent these, your doctor may suggest you eat more fiber, drink plenty of fluids, and exercise regularly. This should help prevent the pouches from becoming infected or inflamed.

In the past, doctors thought people with diverticulosis should avoid certain foods. These included nuts, seeds, and popcorn. Research now suggests these foods aren’t harmful, and won’t cause diverticulitis flare-ups 24. Everyone is different, though. If you think certain foods are making your symptoms worse, stop eating them and talk to your doctor.

If you start feeling symptoms of diverticulitis, call your doctor right away. Untreated diverticulitis can lead to dangerous complications. These include intestinal blockages and openings in the bowel wall.

Figure 1. Diverticular disease

Figure 2. Diverticular disease classification

[Source 5 ]What is the difference between diverticulitis and diverticulosis?

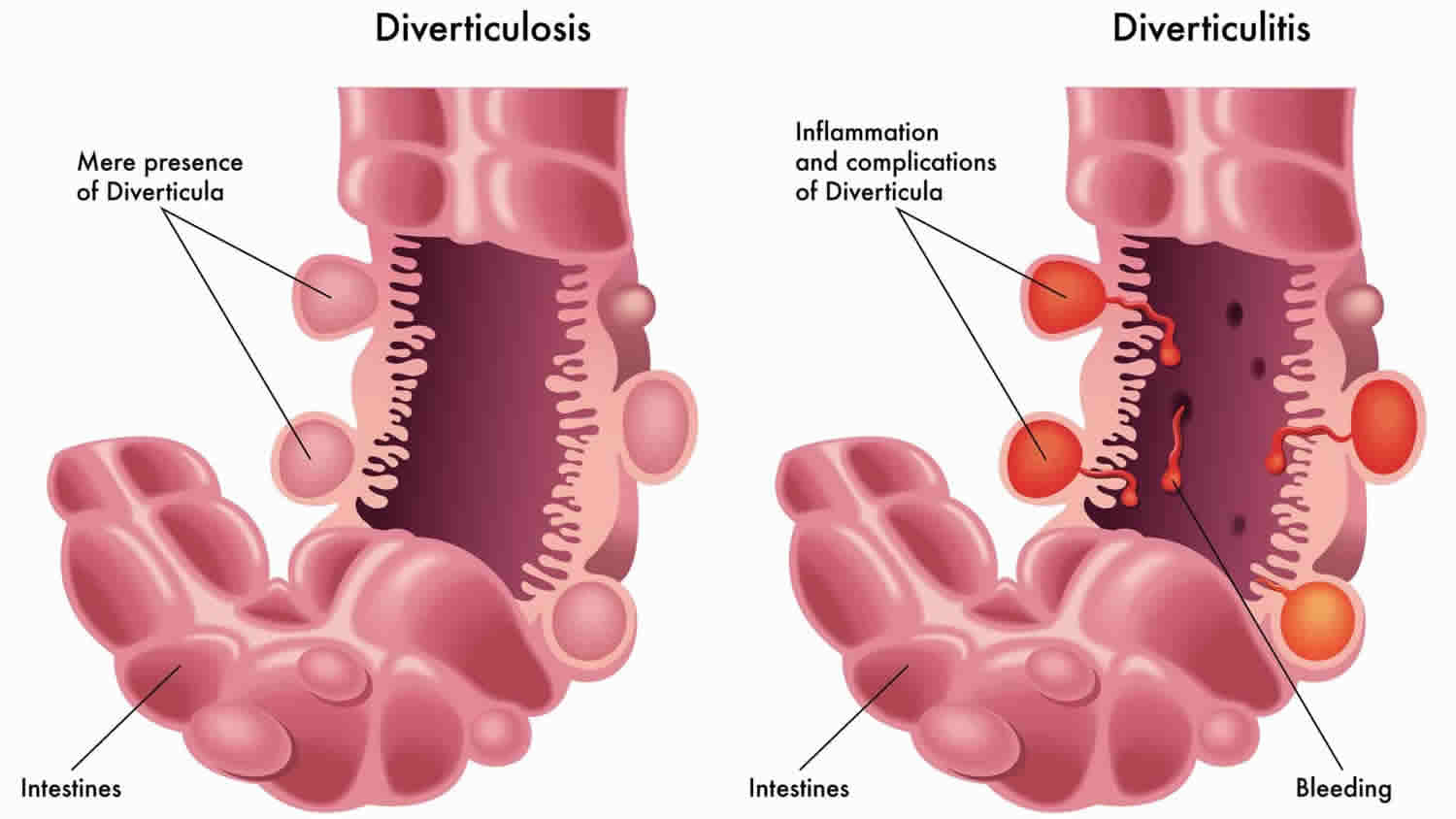

Diverticulosis is a digestive condition that occurs when small pouches or sacs, form and push outward through weak spots in the wall of your colon (large intestine). These pouches form mostly in the lower part of your colon, called the sigmoid colon. One pouch is called a diverticulum. Multiple pouches are called diverticula. Most people who have diverticula in their colon do not have symptoms or problems. However, in some cases, diverticula may lead to symptoms or inflammation.

Diverticulitis occurs when diverticula become inflamed. Diverticulitis can come on suddenly and may lead to serious complications.

Most people with diverticulosis will never develop symptoms or problems. Experts aren’t sure how many people with diverticulosis will develop symptoms if they do not have diverticulitis.

Less than 5% of people with diverticulosis develop diverticulitis 19. In the United States, about 200,000 people are hospitalized for diverticulitis each year 19.

Does what I eat and drink play a role in causing or preventing diverticular disease?

Research suggests that a diet low in fiber and high in red meat may increase your risk of getting diverticulitis—inflammation of one or a few pouches in the wall of your colon. Eating high-fiber foods and eating less red meat may lower the risk.

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025 (https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2021-03/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans-2020-2025.pdf), recommends a dietary fiber intake of 14 grams per 1,000 calories consumed. For example, for a 2,000-calorie diet, the fiber recommendation is 28 grams per day.

Diverticular disease symptoms

Symptoms of diverticular disease depend on whether diverticula—pouches in the wall of the colon—lead to chronic symptoms of diverticula, diverticular bleeding, or diverticulitis. Most people first notice symptoms when they develop complications, such as diverticular bleeding or diverticulitis.

Most people who have diverticulosis are unaware that they have the condition because it usually does not cause symptoms, however some common symptoms may include:

- Abdominal discomfort, pain, cramping and/or bloating.

- The abdominal pain of diverticular disease, usually in your lower left side, tends to come and go and gets worse during or shortly after eating (pooping or farting eases it).

- Changes in bowel motions such as diarrhea or constipation

If your diverticula become infected and inflamed (diverticulitis), you may suddenly:

- get constant, more severe abdominal pain

- have a high temperature

- have diarrhea or constipation

- get mucus or blood in your poo, or bleeding from your bottom (rectal bleeding)

The most common symptom of diverticulitis is severe abdominal pain. It is usually felt in the lower left side of your abdomen. It often comes on suddenly. It can also start out mild and increase over several days. Other symptoms could include fever, nausea, constipation, or diarrhea.

You may have diverticular bleeding if you see a large amount of blood in your stool or in the toilet. See your doctor right away if any of these things happen. Also see your doctor right away if you notice blood coming from your rectum.

Diverticular disease complications

Complications of diverticular disease may include:

- Diverticular bleeding. Diverticular bleeding occurs when a small blood vessel within the wall of a diverticulum pouch bursts. Diverticular bleeding is a common cause of bleeding in the lower digestive tract and can present as painless rectal bleeding (bright red blood). The bleeding may be severe and life-threatening. Diverticular disease is one of the most common causes of acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding.

- Diverticulitis – occurs when there is an infection of the diverticulum (small pouches in the wall of your large intestine or the colon). Symptoms include constant abdominal pain, localized tenderness in the abdomen, nausea, vomiting, constipation or diarrhea, fever and leukocytosis (elevated white blood cells). In severe cases, it may cause perforation or peritonitis.

Diverticular disease causes

Doctors haven’t determined exactly what causes diverticular disease. They think it may be caused by not eating enough fiber. When you don’t eat enough fiber, your stools may not be soft. You can get constipated. Constipation and hard stools increase the pressure in the bowel walls. This pressure may cause the diverticular pouches to form.

Other factors that could contribute to diverticular disease include:

- Genes. Research suggests that certain genes may make some people more likely to develop diverticular disease.

- Lack of exercise

- Obesity

- Smoking

- Decrease in healthy gut bacteria

- Increase in disease-causing bacteria in your colon

- Certain medicines, including steroids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen

Diverticular disease becomes more common as you age. Your risk starts increasing after age 40. Most people have it by the time they’re aged 60 or above.

Scientists are studying other factors that may play a role in diverticular disease. These factors include 25:

- bacteria or stool getting caught in a pouch in your colon

- changes in the microbiome of the intestines

- problems with connective tissue, muscles, or nerves in your colon

- problems with the immune system

Risk factors for developing diverticular disease

Several factors may increase your risk of developing diverticular disease:

- Aging. The incidence of diverticulitis increases with age.

- Obesity. Being seriously overweight increases your odds of developing diverticulitis.

- Smoking. People who smoke cigarettes are more likely than nonsmokers to experience diverticulitis.

- Lack of exercise. Vigorous exercise appears to lower your risk of diverticulitis.

- Diet high in animal fat and low in fiber. A low-fiber diet in combination with a high intake of animal fat seems to increase risk, although the role of low fiber alone isn’t clear.

- Certain medications. Several drugs are associated with an increased risk of diverticulitis, including steroids, opioids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others) and naproxen sodium (Aleve).

Diverticular disease pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of diverticular disease is not completely understood 26. Many factors have been thought to contribute to its pathogenesis including colonic wall structure, colonic motility, diet and fiber intake, obesity and physical activity as well as genetic predisposition 5.

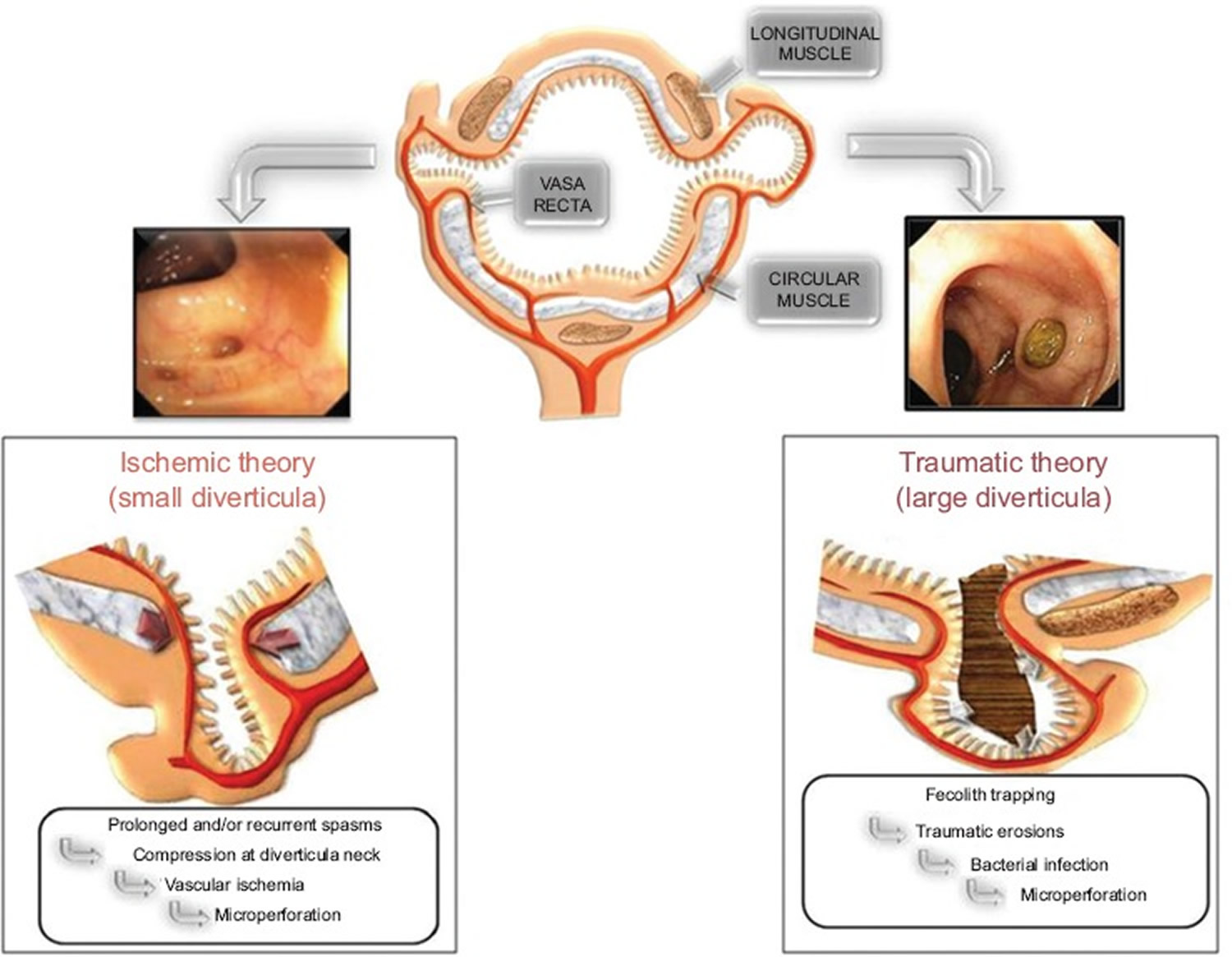

The most accepted current theory that describes the underlying mechanism in acute diverticulitis is “traumatic” damage to the diverticulum and subsequently bacterial proliferation 26. Increased pressure within the colon leads to fecoliths (stony mass of compacted feces) present within the lumen being pushed into the diverticuli, especially larger ones, resulting in stool impaction in the diverticula 27. The entrapped fecolith causes trauma by abrading the mucosa of the diverticular sac leading to local inflammation and bacterial overgrowth. If the proliferating bacteria breach the mucosal wall to involve the full bowel wall, their toxic and gas production may eventually lead to bowel perforation. Furthermore, the irritation and inflammation caused by trapped fecoliths lead to vascular congestion and edema, which in turn cause further obstruction, with secretions from the proliferating bacteria accumulating in the diverticular sac, thus increasing the risk of perforation (Figure 3). This theory could well describe the sequence of events leading to acute diverticulitis in older patients with larger diverticula, and since bacterial overgrowth is the most important pathological factor, antibiotics are the basis of treatment 27.

In younger patients, where the finding of colonic diverticula may be rare, acute diverticulitis may be the result of ischemic damage 27. Studies have demonstrated neuromuscular differences in the affected colonic areas leading to more prolonged and forceful contractile impulses 27. The activity of choline acetyltransferase was shown to be lower in circular muscle of patients with diverticular disease, whilst there was an increase in the number of muscarinic M3 receptors. Furthermore, patients with diverticular disease showed increased sensitivity when administered exogenous acetylcholine, when compared to controls 28. All these factors lead to increased sensitivity to cholinergic denervation leading to excessive contractile impulses in response to normal stimuli in the diverticular wall 27. The “ischaemic” theory suggests that long-standing contractile impulses of the colon cause persistent compression of blood vessels at the diverticular neck. The neck is found in the colonic circular muscular muscle wall, which may be compressed by muscular spasm, triggering ischaemia at the mucosa and micro-perforation (Figure 3). This theory therefore puts forward another possible mechanism for the pathophysiology of acute diverticulitis where fecal entrapment is unlikely and the role of bacteria is not so prominent. Treatment with antibiotics is used more as prophylaxis against opportunistic infections on the damaged colonic mucosa rather than to treat the primary infection itself 27. In fact, The American Gastroenterology Association suggest that ‘antibiotics should be used selectively, rather than routinely, in patients with acute uncomplicated diverticulitis’ 29.

Whenever abdominal pain is present in patients without the acute symptoms of diverticulitis, this is defined as symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease (SUDD) 5. Interestingly, 22% of patients with symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease (SUDD) describe left lower quadrant pain lasting more than 24 hours. This could be produced by the sustained spastic state of the bowel wall which predisposes to mucosal ischaemia in the diverticulum 27. Clemens et al studied the underlying mechanisms which may be implicated in SUDD and it was found that such patients have hypersensitivity in the sigmoid colon bearing diverticula, which is similar to the pathophysiology in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). More studies on the two diseases are required in order to be able to confirm whether patients suffering from IBS are more likely to have diverticulosis and hence be identified as SUDD in view of the chronic abdominal pain 9.

Figure 3. Diverticular disease pathophysiology

Footnotes: The flow-chart describing “traumatic” and “ischemic” theories for diverticulitis.

[Source 27 ]Diverticular disease prevention

The best way to prevent diverticular disease is with a healthy lifestyle and a high-fiber diet.

Research suggests that certain lifestyle factors may lower the risk of developing diverticular disease. These factors include:

- Eating a diet high in fiber and low in red meat

- Being physically active on a regular basis. Vigorous exercise, such as running, has shown a risk reduction for developing complicated diverticulitis by 25%. Light activity, such as walking, is less effective 30.

- Not smoking, or quitting smoking if you smoke

- Reaching and maintaining a healthy weight

You can increase the amount of fiber in your diet by eating more fruits, vegetables and whole-grain foods 31. Also, be sure to drink plenty of fluids and exercise regularly.

In some cases, after a person has diverticulitis without complications, doctors may recommend surgery to remove part of the colon and prevent diverticulitis from occurring again. Whether a doctor recommends surgery depends on the person’s history of diverticulitis, health conditions, and other factors.

Diverticular disease diagnosis

Diverticulosis is often found during examination for other conditions, such as during a colonoscopy, a barium enema or CT scan to diagnose other digestive problems, as many people do not experience symptoms.

If you’re having symptoms, your doctor may check your abdomen for tenderness. He or she may ask about your bowel habits, diet, and any medicines you take. Your doctor may want to do tests to look for diverticular disease. Diverticular disease diagnosis involves a number of tests.

These tests can include:

- Blood tests. Your doctor will take a blood sample from you and send the sample to a lab. Doctors may use blood tests to check for signs of diverticulitis or its complications.

- Stool test. Doctors may order a stool test to help find out if you have diverticular disease or another health problem, such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Your doctor will give you a container for catching and holding a stool sample. You will receive instructions on where to send or take the kit for testing.

- Urine test to check for signs of infection.

- A pregnancy test for women of childbearing age, to rule out pregnancy as a cause of abdominal pain.

- A liver enzyme test, to rule out liver-related causes of abdominal pain.

- CT (computed tomography) scan. CT scan uses a combination of x-rays and computer technology to create images that allow your doctor to see if you have pouches in your colon. It can show if any are inflamed or infected. CT scan is the most common test for diagnosing diverticular disease. CT can also indicate the severity of diverticulitis and guide treatment.

- Barium enema also called a lower GI series. This test injects liquid barium into your rectum and colon. Then X-rays are taken. The barium makes your colon more visible on the X-rays. Barium enema is used for patients where a colonoscopy can be difficult or dangerous.

- Flexible sigmoidoscopy. In this test, your doctor puts a thin, flexible tube with a light on the end into your rectum. The tube is connected to a tiny video camera. This allows your doctor to look at your rectum and the last part of your colon.

- Colonoscopy. In this procedure, the video camera and light on a flexible tube go through your rectum and your whole colon. This allows your doctor to see the inside of your entire large intestine. Before the test, you are given medicine to make you relaxed and sleepy. A colonoscopy may be uncomfortable, but it’s usually not painful.

Diverticular disease treatment

Your doctor will recommend treatments based on whether you have chronic symptoms of diverticula, diverticulitis, or other complications of diverticular disease.

As most people with diverticulosis do not experience any symptoms, treatment is not required. Diverticulosis treatment focuses on preventing the pouches from getting inflamed or infected. Your doctor may recommend:

- A high-fiber diet. Generally, adults should aim to eat 30g of fiber a day. Good sources of fiber include fresh and dried fruits, vegetables, beans and pulses, nuts, cereals and starchy foods.

- Fiber supplements. Fiber supplements, usually in the form of sachets of powder that you mix with water, are also available from pharmacists and health food shops.

- Medicines to reduce pain and inflammation. You can take acetaminophen (paracetamol) to help relieve any pain. Do not take nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). NSAIDs may increase the chance of diverticulitis complications. Antispasmodics may be used to relax spasms in the colon that cause abdominal cramping or discomfort.

- Antibiotics. Antibiotics to treat infection, although new guidelines state that in very mild cases, they may not be needed.

- Probiotics

Gradually increasing your fiber intake over a few weeks and drinking plenty of fluids can help prevent side effects associated with a high-fiber diet, such as bloating and farting. There is strong evidence that eating plenty of fiber (commonly referred to as roughage) is associated with a lower risk of heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes and bowel cancer.

Fiber supplements may be recommended to help bulk and soften the stool and make bowel movements easier to pass. Medications may be used to relax spasms in the colon that cause abdominal cramping or discomfort.

Surgical treatment will depend on the severity and frequency of complications from diverticular disease. Your specialist may treat the disease with antibiotics, fluid replacement, and in some cases blood transfusion.

For mild cases of diverticulitis, your doctor may recommend rest and a liquid diet until symptoms ease. He or she may also prescribe medicine to treat the infection.

For severe cases of diverticulitis or diverticular bleeding, you may need to stay in the hospital. There you can get intravenous medicine and the rest you need. Some people need surgery to remove the pouches and diseased parts of their colon.

Diverticular disease complications treatment

Doctors typically treat the complications of diverticular disease in a hospital.

Diverticular bleeding

If you have bleeding from your rectum—even a small amount—you should see a doctor right away. In some cases, diverticular bleeding may stop by itself and may not require treatment. In other cases, doctors may need to find the source of the diverticular bleeding and stop it, or give blood transfusions if a lot of blood has been lost.

Doctors can find and stop diverticular bleeding with procedures such as:

- Colonoscopy. During a colonoscopy, a doctor can insert special tools through the colonoscope to stop the bleeding.

- Angiogram, a special kind of x-ray that uses dye to detect blood vessels in the colon. During an angiogram, a radiologist can inject medicines or other materials into blood vessels to stop the bleeding.

- Surgery.

Diverticulitis complications

The most common complication of diverticulitis is developing abscesses. Doctors may recommend different treatments for abscesses. Doctors may:

- prescribe antibiotics to treat small abscesses

- drain abscesses that are large or don’t improve with antibiotics. These are usually treated with a technique known as percutaneous drainage, which is done by a radiologist.

- recommend surgery after a large abscess heals, to prevent the abscess from coming back

Doctors typically recommend surgery to treat other diverticulitis complications, including:

- fistulas

- intestinal obstruction

- perforation

- peritonitis

Surgery usually involves removing the affected section of your large intestine. This is known as a colectomy. This is the treatment for rare complications such as fistulas, peritonitis or a blockage in your intestines. After a colectomy, you may have a temporary or permanent colostomy, where one end of your bowel is diverted through an opening in your abdomen.

Diverticular disease diet

If you have chronic symptoms of diverticular disease or if you had diverticulitis in the past, your doctor may recommend eating more foods that are high in fiber. Talk with your doctor or a dietitian, to plan meals with the right amount of fiber for you. Health care professionals may recommend increasing the amount of fiber you eat a little at a time, so your body gets used to the change. The amount of fiber in a portion of food is listed on the food’s Nutrition Facts label. Some examples of fiber-rich foods are listed in the table below.

Table 1. Examples of fiber-rich foods

| FOOD b,c | STANDARD PORTION d | FIBER (g) | |

| Grains | |||

| Ready-to-eat cereal, high fiber, unsweetened | 1/2 cup | 14 | |

| Ready-to-eat cereal, whole grain kernels | 1/2 cup | 7.5 | |

| Ready-to-eat cereal, wheat, shredded | 1 cup | 6.2 | |

| Popcorn | 3 cups | 5.8 | |

| Ready-to-eat cereal, bran flakes | 3/4 cup | 5.5 | |

| Bulgur, cooked | 1/2 cup | 4.1 | |

| Spelt, cooked | 1/2 cup | 3.8 | |

| Teff, cooked | 1/2 cup | 3.6 | |

| Barley, pearled, cooked | 1/2 cup | 3 | |

| Ready-to-eat cereal, toasted oat | 1 cup | 3 | |

| Oat bran | 1/2 cup | 2.9 | |

| Crackers, whole wheat | 1 ounce | 2.9 | |

| Chapati or roti, whole wheat | 1 ounce | 2.8 | |

| Tortillas, whole wheat | 1 ounce | 2.8 | |

| Vegetables | |||

| Artichoke, cooked | 1 cup | 9.6 | |

| Navy beans, cooked | 1/2 cup | 9.6 | |

| Small white beans, cooked | 1/2 cup | 9.3 | |

| Yellow beans, cooked | 1/2 cup | 9.2 | |

| Lima beans, cooked | 1 cup | 9.2 | |

| Green peas, cooked | 1 cup | 8.8 | |

| Adzuki beans, cooked | 1/2 cup | 8.4 | |

| French beans, cooked | 1/2 cup | 8.3 | |

| Split peas, cooked | 1/2 cup | 8.2 | |

| Breadfruit, cooked | 1 cup | 8 | |

| Lentils, cooked | 1/2 cup | 7.8 | |

| Lupini beans, cooked | 1/2 cup | 7.8 | |

| Mung beans, cooked | 1/2 cup | 7.7 | |

| Black turtle beans, cooked | 1/2 cup | 7.7 | |

| Pinto beans, cooked | 1/2 cup | 7.7 | |

| Cranberry (roman) beans, cooked | 1/2 cup | 7.6 | |

| Black beans, cooked | 1/2 cup | 7.5 | |

| Fufu, cooked | 1 cup | 7.4 | |

| Pumpkin, canned | 1 cup | 7.1 | |

| Taro root (dasheen or yautia), cooked | 1 cup | 6.7 | |

| Brussels sprouts, cooked | 1 cup | 6.4 | |

| Chickpeas (garbanzo beans), cooked | 1/2 cup | 6.3 | |

| Sweet potato, cooked | 1 cup | 6.3 | |

| Great northern beans, cooked | 1/2 cup | 6.2 | |

| Parsnips, cooked | 1 cup | 6.2 | |

| Nettles, cooked | 1 cup | 6.1 | |

| Jicama, raw | 1 cup | 5.9 | |

| Winter squash, cooked | 1 cup | 5.7 | |

| Pigeon peas, cooked | 1/2 cup | 5.7 | |

| Kidney beans, cooked | 1/2 cup | 5.7 | |

| White beans, cooked | 1/2 cup | 5.7 | |

| Black-eyed peas, dried and cooked | 1/2 cup | 5.6 | |

| Cowpeas, dried and cooked | 1/2 cup | 5.6 | |

| Yam, cooked | 1 cup | 5.3 | |

| Broccoli, cooked | 1 cup | 5.2 | |

| Tree fern, cooked | 1 cup | 5.2 | |

| Luffa gourd, cooked | 1 cup | 5.2 | |

| Soybeans, cooked | 1/2 cup | 5.2 | |

| Turnip greens, cooked | 1 cup | 5 | |

| Drumstick pods (moringa), cooked | 1 cup | 5 | |

| Avocado | 1/2 cup | 5 | |

| Cauliflower, cooked | 1 cup | 4.9 | |

| Kohlrabi, raw | 1 cup | 4.9 | |

| Carrots, cooked | 1 cup | 4.8 | |

| Collard greens, cooked | 1 cup | 4.8 | |

| Kale, cooked | 1 cup | 4.7 | |

| Fava beans, cooked | 1/2 cup | 4.6 | |

| Chayote (mirliton), cooked | 1 cup | 4.5 | |

| Snow peas, cooked | 1 cup | 4.5 | |

| Pink beans, cooked | 1/2 cup | 4.5 | |

| Spinach, cooked | 1 cup | 4.3 | |

| Escarole, cooked | 1 cup | 4.2 | |

| Beet greens, cooked | 1 cup | 4.2 | |

| Salsify, cooked | 1 cup | 4.2 | |

| Cabbage, savoy, cooked | 1 cup | 4.1 | |

| Cabbage, red, cooked | 1 cup | 4.1 | |

| Wax beans, snap, cooked | 1 cup | 4.1 | |

| Edamame, cooked | 1/2 cup | 4.1 | |

| Okra, cooked | 1 cup | 4 | |

| Green beans, snap, cooked | 1 cup | 4 | |

| Hominy, canned | 1 cup | 4 | |

| Corn, cooked | 1 cup | 4 | |

| Potato, baked, with skin | 1 medium | 3.9 | |

| Lambsquarters, cooked | 1 cup | 3.8 | |

| Lotus root, cooked | 1 cup | 3.8 | |

| Swiss chard, cooked | 1 cup | 3.7 | |

| Mustard spinach, cooked | 1 cup | 3.6 | |

| Carrots, raw | 1 cup | 3.6 | |

| Hearts of palm, canned | 1 cup | 3.5 | |

| Mushrooms, cooked | 1 cup | 3.4 | |

| Bamboo shoots, raw | 1 cup | 3.3 | |

| Yardlong beans, cooked | 1/2 cup | 3.3 | |

| Turnip, cooked | 1 cup | 3.1 | |

| Red bell pepper, raw | 1 cup | 3.1 | |

| Rutabaga, cooked | 1 cup | 3.1 | |

| Plantains, cooked | 1 cup | 3.1 | |

| Nopales, cooked | 1 cup | 3 | |

| Dandelion greens, cooked | 1 cup | 3 | |

| Cassava (yucca), cooked | 1 cup | 3 | |

| Asparagus, cooked | 1 cup | 2.9 | |

| Taro leaves, cooked | 1 cup | 2.9 | |

| Onions, cooked | 1 cup | 2.9 | |

| Cabbage, cooked | 1 cup | 2.8 | |

| Mustard greens, cooked | 1 cup | 2.8 | |

| Beets, cooked | 1 cup | 2.8 | |

| Celeriac, raw | 1 cup | 2.8 | |

| Fruit | |||

| Sapote or Sapodilla | 1 cup | 9.5 | |

| Durian | 1 cup | 9.2 | |

| Guava | 1 cup | 8.9 | |

| Nance | 1 cup | 8.4 | |

| Raspberries | 1 cup | 8 | |

| Loganberries | 1 cup | 7.8 | |

| Blackberries | 1 cup | 7.6 | |

| Soursop | 1 cup | 7.4 | |

| Boysenberries | 1 cup | 7 | |

| Gooseberries | 1 cup | 6.5 | |

| Pear, Asian | 1 medium | 6.5 | |

| Blueberries, wild | 1 cup | 6.2 | |

| Passionfruit | 1/4 cup | 6.1 | |

| Persimmon | 1 fruit | 6 | |

| Pear | 1 medium | 5.5 | |

| Kiwifruit | 1 cup | 5.4 | |

| Grapefruit | 1 fruit | 5 | |

| Apple, with skin | 1 medium | 4.8 | |

| Cherimoya | 1 cup | 4.8 | |

| Durian | 1/2 cup | 4.6 | |

| Starfruit | 1 cup | 3.7 | |

| Orange | 1 medium | 3.7 | |

| Figs, dried | 1/4 cup | 3.7 | |

| Blueberries | 1 cup | 3.6 | |

| Pomegranate seeds | 1/2 cup | 3.5 | |

| Mandarin orange | 1 cup | 3.5 | |

| Tangerine (tangelo) | 1 cup | 3.5 | |

| Pears, dried | 1/4 cup | 3.4 | |

| Peaches, dried | 1/4 cup | 3.3 | |

| Banana | 1 medium | 3.2 | |

| Apricots | 1 cup | 3.1 | |

| Prunes or dried plum | 1/4 cup | 3.1 | |

| Strawberries | 1 cup | 3 | |

| Dates | 1/4 cup | 3 | |

| Blueberries, dried | 1/4 cup | 3 | |

| Cherries | 1 cup | 2.9 | |

| Protein Foods | |||

| Wocas, yellow pond lily seeds | 1 ounce | 5.4 | |

| Pumpkin seeds, whole | 1 ounce | 5.2 | |

| Coconut | 1 ounce | 4.6 | |

| Chia seeds | 1 Tbsp | 4.1 | |

| Almonds | 1 ounce | 3.5 | |

| Chestnuts | 1 ounce | 3.3 | |

| Sunflower seeds | 1 ounce | 3.1 | |

| Pine nuts | 1 ounce | 3 | |

| Pistachio nuts | 1 ounce | 2.9 | |

| Flax seeds | 1 Tbsp | 2.8 | |

| Hazelnuts (filberts) | 1 ounce | 2.8 | |

Footnotes:

a All foods listed are assumed to be in nutrient-dense forms; lean or low-fat and prepared with minimal added sugars, saturated fat, or sodium.

b Some fortified foods and beverages are included. Other fortified options may exist on the market, but not all fortified foods are nutrient-dense. For example, some foods with added sugars may be fortified and would not be examples in the lists provided here.

c Some foods or beverages are not appropriate for all ages, (e.g., nuts, popcorn), particularly young children for whom some foods could be a choking hazard

d Portions listed are not recommended serving sizes. Two lists—in ‘standard’ and ‘smaller’ portions–are provided for each dietary component. Standard portions provide at least 2.8 g of dietary fiber. Smaller portions are generally one half of a standard portion.

[Source 32 ]Diverticulitis

Diverticulitis occurs when the diverticula become inflamed or infected, caused by bacteria trapped inside one of the bulges. This can lead to complications, such as an abscess next to the intestine.

Diverticulitis causes

Diverticular disease starts with an out-pouching of the mucosa of the colonic wall. Diverticulitis occurs when the diverticula tear, resulting in inflammation, and in some cases, infection.

The presumed mechanism of diverticulitis is an overgrowth of bacteria due to obstruction of the diverticular base by feces with micro-perforations 3. This theory has been challenged in recent years as some studies demonstrate that resolution of uncomplicated diverticulitis may occur without antibiotics in selected cases 33.

Diverticulitis signs and symptoms

The signs and symptoms of diverticulitis include:

- Abdominal pain, which may be constant and persist for several days. The lower left side of the abdomen is the usual site of the pain. Sometimes, however, the right side of the abdomen is more painful, especially in people of Asian descent. The pain caused by diverticulitis is typically severe and comes on suddenly, although the pain may also be mild and worsen over several days. The intensity of the pain may change over time.

- Nausea and vomiting.

- Fever and chills.

- Abdominal tenderness.

- Constipation or, less commonly, diarrhea.

Get medical attention anytime you have constant, unexplained abdominal pain, particularly if you also have a fever and constipation or diarrhea.

Diverticulitis complications

Diverticulitis may lead to complications such as:

- Abscess formation (commonest), a painful, swollen, pus-filled area caused by infection

- Fistula, an abnormal passage or tunnel between the colon and another part of the body, such as the bladder or vagina

- Intestinal obstruction, a partial or total blockage of the movement of food, fluids, air, or stool through your intestines

- Intestinal stricture

- Intestinal perforation, or a hole, in your colon

- Peritonitis, an infection of the lining of the abdominal cavity

- Sepsis

Those infected with HIV or those on immunosuppressants are more likely to develop perforation 34.

Diverticulitis treatment

Diverticulitis treatment depends on the severity of your signs and symptoms. For people who have diverticulitis without complications, doctors may recommend treatment at home. However, people typically need treatment in a hospital if they have severe diverticulitis, diverticulitis with complications, or a high risk for complications.

Treatments for diverticulitis may include:

- Antibiotics, although not all people with diverticulitis need these medicines.

- Clear liquid diet for a short time to rest the colon. Your doctor may suggest slowly adding solid foods to your diet as your symptoms improve.

- Medicines for pain. Doctors may recommend antispasmodics or acetaminophen (paracetamol) instead of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). NSAIDs may increase the chance of diverticulitis complications.

- Some experts suspect that people who develop diverticulitis may not have enough good bacteria in their colons. Probiotics — foods or supplements that contain beneficial bacteria — are sometimes suggested as a way to prevent diverticulitis. But that advice hasn’t been scientifically validated.

If your diverticulitis doesn’t improve with treatment or if it leads to complications, you may need surgery to remove part of your colon, called a colectomy or colon resection.

Uncomplicated diverticulitis treatment

If your symptoms are mild, you may be treated at home. Your doctor is likely to recommend:

- Antibiotics to treat infection, although new guidelines state that in very mild cases, they may not be needed. Oral antibiotics, such as ciprofloxacin and metronidazole or amoxicillin-clavulanate, are prescribed for 7 to 10 days with recommendations to minimize oral intake until the pain has resolved 35.

- A liquid diet for a few days while your bowel heals. Once your symptoms improve, you can gradually add solid food to your diet.

This treatment is successful in most people with uncomplicated diverticulitis.

Complicated diverticulitis treatment

If you have a severe attack or have other health problems, you’ll likely need to be hospitalized. Treatment generally involves:

- Intravenous antibiotics

- Insertion of a tube to drain an abdominal abscess, if one has formed

Surgery

You’ll likely need surgery to treat diverticulitis if:

- You have a complication, such as a bowel abscess, fistula or obstruction, or a puncture (perforation) in the bowel wall

- You have had multiple episodes of uncomplicated diverticulitis

- You have a weakened immune system

There are two main types of surgery:

- Primary bowel resection. The surgeon removes diseased segments of your intestine and then reconnects the healthy segments (anastomosis). This allows you to have normal bowel movements. Depending on the amount of inflammation, you may have open surgery or a minimally invasive (laparoscopic) procedure.

- Bowel resection with colostomy. If you have so much inflammation that it’s not possible to rejoin your colon and rectum, the surgeon will perform a colostomy. An opening (stoma) in your abdominal wall is connected to the healthy part of your colon. Waste passes through the opening into a bag. Once the inflammation has eased, the colostomy may be reversed and the bowel reconnected.

Follow-up care

Your doctor may recommend colonoscopy six weeks after you recover from diverticulitis, especially if you haven’t had the test in the previous year 35. There doesn’t appear to be a direct link between diverticular disease and colon or rectal cancer. But colonoscopy — which is risky during a diverticulitis attack — can exclude colon cancer as a cause of your symptoms.

After successful treatment, your doctor may recommend surgery to prevent future episodes of diverticulitis. The decision on surgery is an individual one and is often based on the frequency of attacks and whether complications have occurred.

Historically, elective sigmoid colectomy used to be performed after the second bout of uncomplicated diverticulitis 3. However, more recent evidence has disproved the benefit of this approach. Firstly, the recurrence rate of uncomplicated diverticulitis is lower than previously estimated, ranging from 13 to 23%. Secondly, the incidence of complicated recurrent episodes that may require a stoma is also low, approximately 6%. Therefore, current recommendations emphasize that selection criteria for elective surgery should be individualized according to the number, severity, and frequency of diverticulitis episodes, persistent symptomatology after an episode of diverticulitis, and the immunologic status of the patient 3. These criteria merit consideration in the context of the patient’s age, comorbidities, and social history. Finally, routine sigmoid colectomy in patients younger than 50 years of age is no longer the recommended therapeutic path 36. Younger patients should receive the same treatment as their older counterparts.

Regardless of the indication and or technique used (open, laparoscopic, or robotic) when performing an elective sigmoid colectomy for diverticulitis, it requires removing the entire sigmoid colon, the proximal and distal anastomotic sites must appear healthy and well perfused, and the anastomosis performed without tension.

Approximately 1% of patients with an acute episode of diverticulitis will require surgical intervention during that episode 37. Patients presenting with signs of peritonitis are candidates for emergent surgery. When intraoperative findings confirm perforated diverticulitis, the traditional operation is a Hartmann procedure, which includes resection of the sigmoid colon, preservation of the rectum in the form of a rectal pouch, and creation of an end colostomy. This procedure effectively eliminates the risk of an anastomotic leak, and patients are considered for colostomy reversal in 3 to 6 months. However, due to old age and associated comorbidities, nearly 30% of patients undergoing a Hartmann procedure never have colostomy reversal 35. A second option for patients with Hinchey 3 and 4 diseases is a primary colorectal anastomosis with a proximal diverting ileostomy. Initial retrospective evaluation of this surgical modality shows a decreased overall mortality after performing a primary anastomosis. However, randomized controlled studies comparing a Hartmann procedure to the primary anastomosis with proximal diversion are not yet available 38. An old approach, no longer considered in the surgical management of complicated diverticulitis, consisted of leaving the inflamed or perforated sigmoid colon in situ and placement of a proximal stoma with the plan of second and then third stage procedures.

Diverticulitis prognosis

The prognosis of diverticulitis depends on the severity of the illness and the presence of complications. Immunocompromised patients have higher morbidity and mortality as a result of sigmoid diverticulitis 39.

After the first incident of acute diverticulitis, the five-year recurrence rate is approximately 20% 40. Several studies have demonstrated the significant link between increased BMI (body mass index) or obesity and the risk of developing diverticulitis 41.

- InformedHealth.org [Internet]. Cologne, Germany: Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG); 2006-. Diverticular disease and diverticulitis: Overview. 2018 May 17. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507004[↩]

- Munie, S. T., & Nalamati, S. (2018). Epidemiology and Pathophysiology of Diverticular Disease. Clinics in colon and rectal surgery, 31(4), 209–213. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0037-1607464[↩][↩][↩]

- Carr S, Velasco AL. Colon Diverticulitis. [Updated 2021 Nov 14]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541110[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Strate LL. Lifestyle factors and the course of diverticular disease. Dig Dis. 2012;30(1):35-45. doi: 10.1159/000335707[↩]

- Rezapour, M., Ali, S., & Stollman, N. (2018). Diverticular Disease: An Update on Pathogenesis and Management. Gut and liver, 12(2), 125–132. https://doi.org/10.5009/gnl16552[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Wheat CL, Strate LL. Trends in hospitalization for diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding in the United States from 2000 to 2010. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2016;14(1):96–103.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.03.030[↩][↩]

- Peery, A. F., & Sandler, R. S. (2013). Diverticular disease: reconsidering conventional wisdom. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association, 11(12), 1532–1537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2013.04.048[↩]

- Strate LL, Modi R, Cohen E, Spiegel BM. Diverticular disease as a chronic illness: evolving epidemiologic and clinical insights. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012 Oct;107(10):1486-93. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.194[↩][↩]

- Clemens, C. H., Samsom, M., Roelofs, J., van Berge Henegouwen, G. P., & Smout, A. J. (2004). Colorectal visceral perception in diverticular disease. Gut, 53(5), 717–722. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2003.018093[↩][↩]

- Bassotti, G., Battaglia, E., Bellone, G., Dughera, L., Fisogni, S., Zambelli, C., Morelli, A., Mioli, P., Emanuelli, G., & Villanacci, V. (2005). Interstitial cells of Cajal, enteric nerves, and glial cells in colonic diverticular disease. Journal of clinical pathology, 58(9), 973–977. https://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.2005.026112[↩]

- Freeman H. J. (2016). Segmental colitis associated diverticulosis syndrome. World journal of gastroenterology, 22(36), 8067–8069. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i36.8067[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Tursi A, Elisei W, Giorgetti GM, Aiello F, Brandimarte G. Inflammatory manifestations at colonoscopy in patients with colonic diverticular disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011 Feb;33(3):358-65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04530.x[↩]

- Freeman HJ. Natural history and long-term clinical behavior of segmental colitis associated with diverticulosis (SCAD syndrome). Dig Dis Sci. 2008 Sep;53(9):2452-7. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-0173-y[↩]

- Painter, N. S., & Burkitt, D. P. (1971). Diverticular disease of the colon: a deficiency disease of Western civilization. British medical journal, 2(5759), 450–454. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1796198/pdf/brmedj02261-0052.pdf[↩]

- Feingold D, Steele SR, Lee S, Kaiser A, Boushey R, Buie WD, Rafferty JF. Practice parameters for the treatment of sigmoid diverticulitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014 Mar;57(3):284-94. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000075[↩]

- Manousos, O., Day, N. E., Tzonou, A., Papadimitriou, C., Kapetanakis, A., Polychronopoulou-Trichopoulou, A., & Trichopoulos, D. (1985). Diet and other factors in the aetiology of diverticulosis: an epidemiological study in Greece. Gut, 26(6), 544–549. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1432747/pdf/gut00379-0008.pdf[↩]

- Humes DJ, Fleming KM, Spiller RC, West J. Concurrent drug use and the risk of perforated colonic diverticular disease: a population-based case-control study. Gut. 2011 Feb;60(2):219-24. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.217281[↩]

- Biondo S, Golda T, Kreisler E, Espin E, Vallribera F, Oteiza F, Codina-Cazador A, Pujadas M, Flor B. Outpatient versus hospitalization management for uncomplicated diverticulitis: a prospective, multicenter randomized clinical trial (DIVER Trial). Ann Surg. 2014 Jan;259(1):38-44. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182965a11[↩]

- Strate LL, Morris AM. Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatment of diverticulitis. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(5):1282–1298.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.12.033[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Nguyen, G. C., Sam, J., & Anand, N. (2011). Epidemiological trends and geographic variation in hospital admissions for diverticulitis in the United States. World journal of gastroenterology, 17(12), 1600–1605. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i12.1600[↩]

- Granlund J, Svensson T, Olén O, Hjern F, Pedersen NL, Magnusson PK, Schmidt PT. The genetic influence on diverticular disease–a twin study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012 May;35(9):1103-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05069.x[↩]

- Rajendra S, Ho JJ. Colonic diverticular disease in a multiracial Asian patient population has an ethnic predilection. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005 Aug;17(8):871-5. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200508000-00015[↩]

- Strate LL, Erichsen R, Baron JA, Mortensen J, Pedersen JK, Riis AH, Christensen K, Sørensen HT. Heritability and familial aggregation of diverticular disease: a population-based study of twins and siblings. Gastroenterology. 2013 Apr;144(4):736-742.e1; quiz e14. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.12.030[↩]

- Strate, L. L., Liu, Y. L., Syngal, S., Aldoori, W. H., & Giovannucci, E. L. (2008). Nut, corn, and popcorn consumption and the incidence of diverticular disease. JAMA, 300(8), 907–914. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.300.8.907[↩]

- Symptoms & Causes of Diverticular Disease. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/diverticulosis-diverticulitis/symptoms-causes[↩]

- Piscopo, N., & Ellul, P. (2020). Diverticular Disease: A Review on Pathophysiology and Recent Evidence. The Ulster medical journal, 89(2), 83–88. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7576390[↩][↩]

- Zullo A. (2018). Medical hypothesis: speculating on the pathogenesis of acute diverticulitis. Annals of gastroenterology, 31(6), 747–749. https://doi.org/10.20524/aog.2018.0315[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Golder M, Burleigh DE, Belai A, Ghali L, Ashby D, Lunniss PJ, Navsaria HA, Williams NS. Smooth muscle cholinergic denervation hypersensitivity in diverticular disease. Lancet. 2003 Jun 7;361(9373):1945-51. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13583-0[↩]

- Stollman N, Smalley W, Hirano I; AGA Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Guideline on the Management of Acute Diverticulitis. Gastroenterology. 2015 Dec;149(7):1944-9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.10.003[↩]

- Böhm SK, Kruis W. Lifestyle and other risk factors for diverticulitis. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2017 Jun;63(2):110-118. doi: 10.23736/S1121-421X.17.02371-6[↩]

- Diverticular disease: diagnosis and management. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2019 Nov 27. (NICE Guideline, No. 147.) Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK558086[↩]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Food sources of dietary fiber. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025. 9th edition. December 2020. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/resources/2020-2025-dietary-guidelines-online-materials/food-sources-select-nutrients/food-0[↩]

- Schieffer KM, Kline BP, Yochum GS, Koltun WA. Pathophysiology of diverticular disease. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Jul;12(7):683-692. doi: 10.1080/17474124.2018.1481746[↩]

- Jacobs DO. Clinical practice. Diverticulitis. N Engl J Med. 2007 Nov 15;357(20):2057-66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp073228[↩]

- Young-Fadok TM. Diverticulitis. N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 25;379(17):1635-1642. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1800468. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2019 Jan 31;380(5):502.[↩][↩][↩]

- Feingold D, Steele SR, Lee S, Kaiser A, Boushey R, Buie WD, Rafferty JF. Practice parameters for the treatment of sigmoid diverticulitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014 Mar;57(3):284-94.[↩]

- Zoog E, Giles WH, Maxwell RA. An Update on the Current Management of Perforated Diverticulitis. Am Surg. 2017 Dec 01;83(12):1321-1328.[↩]

- Shaban F, Carney K, McGarry K, Holtham S. Perforated diverticulitis: To anastomose or not to anastomose? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2018 Oct;58:11-21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.08.009[↩]

- Brandl, A., Kratzer, T., Kafka-Ritsch, R., Braunwarth, E., Denecke, C., Weiss, S., Atanasov, G., Sucher, R., Biebl, M., Aigner, F., Pratschke, J., & Öllinger, R. (2016). Diverticulitis in immunosuppressed patients: A fatal outcome requiring a new approach?. Canadian journal of surgery. Journal canadien de chirurgie, 59(4), 254–261. https://doi.org/10.1503/cjs.012915[↩]

- Peery AF. Recent Advances in Diverticular Disease. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2016 Jul;18(7):37. doi: 10.1007/s11894-016-0513-1[↩]

- Strate, L. L., Liu, Y. L., Aldoori, W. H., Syngal, S., & Giovannucci, E. L. (2009). Obesity increases the risks of diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding. Gastroenterology, 136(1), 115–122.e1. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.025[↩]