Fibromyalgia syndrome

Fibromyalgia syndrome also called fibromyalgia, fibro or FMS, is a chronic musculoskeletal pain syndrome characterized widespread body pain, stiffness, and tenderness of the muscles, tendons, and joints 1. Fibromyalgia syndrome is also characterized by restless sleep, tiredness, fatigue, anxiety, depression, and disturbances in bowel functions. But all of these symptoms are common to many other conditions. People with fibromyalgia may be more sensitive to pain than people who don’t have it. This is called abnormal pain perception processing 2. People who have fibromyalgia often experience chronic pain (pain that lasts a long time – possibly your entire life). People with fibromyalgia also have “tender points” on their body. Tender points are specific places on the neck, shoulders, back, hips, arms, elbows and legs. These points hurt when pressure is put on them. And because fibromyalgia symptoms can occur alone or along with other conditions, it can take time to tease out which symptom is caused by what problem. To make things even more confusing, fibromyalgia symptoms can come and go over time. That’s why it can take a long time to go from fibromyalgia symptoms to a fibromyalgia diagnosis.

People with fibromyalgia may also have other symptoms or co-exists with other conditions, such as 3:

- Increased sensitivity to pain.

- Fatigue (extreme tiredness) or chronic fatigue syndrome

- Muscle stiffness

- Difficulty sleeping

- Trouble sleeping

- Morning stiffness

- Migraine and other types of headaches

- Painful menstrual periods

- Tingling or numbness in hands and feet

- Problems with mental processes known as “fibro-fog” – such as problems with memory, thinking and concentration

- Pain in the face or jaw, including disorders of the jaw know as temporomandibular joint syndrome (also known as TMJ disorders).

- Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) – a digestive condition that causes abdominal pain, constipation and bloating

- Interstitial cystitis or painful bladder syndrome

- Anxiety

- Depression

- Postural tachycardia syndrome

There will be times when your fibromyalgia may “flare up” and your symptoms will be worse. Other times, you will feel much better. The good news is that your symptoms can be managed.

Fibromyalgia was first described in the 19th century. In the 1970s and 1980s, a cause of the disease involving the central nervous system was discovered 4. In 1950, Graham introduced the concept of “pain syndrome” in the absence of a specific organic disease 5. The term “fibromyalgia” was later coined by Smythe and Moldofsky following the identification of regions of extreme tenderness known as “pain points” 6. These points are defined as areas of hyperalgesia or allodynia when a pressure of about 4 kg causes pain 7. In 1990, the committee of the American College of Rheumatology drew up diagnostic criteria, which have only recently been modified 8, 9. According to the American College of Rheumatology, the diagnosis of fibromyalgia includes two variables: (1) bilateral pain above and below the waist, characterized by centralized pain, and (2) chronic generalized pain that lasts for at least three months, characterized by pain on palpation in at least 11 of 18 specific body sites (see Figure 1) 10.

No one knows what causes fibromyalgia. Anyone can get it, but fibromyalgia is most common in middle-aged women (7 times as many women as men). People with rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune diseases are particularly likely to develop fibromyalgia.

The prevalence of fibromyalgia syndrome in adults is about 2 to 3% in the USA and other countries 11. Fibromyalgia syndrome is higher among women (3.4%) than men (0.5%). It increases with age 12. The average age of diagnosis in adults is around 40-50 years, and 13-15 years for children and adolescents 13. Between the ages of 20 to 55 years, the cause of generalized, musculoskeletal pain in most women is fibromyalgia 14. The prevalence in adolescents has been found to be similar to those in adults in many studies. Amongst the patients referred to a tertiary care pain clinic, more than 40% met the criteria for fibromyalgia 15. The risk for fibromyalgia is higher if you have an existent rheumatic disease.

Fibromyalgia is more common in women than men because of the following 14:

- Higher levels of anxiety

- Use of maladaptive coping methods

- Altered behavior in response to pain

- Higher levels of depression

- Altered input to the central nervous system (CNS) and hormonal effects of the menstrual cycle.

Anyone can get fibromyalgia, though it occurs most often in women and often starts in middle age. If you have certain other diseases, you may be more likely to have fibromyalgia. These diseases include:

- Rheumatoid arthritis.

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (commonly called lupus or SLE).

- Ankylosing spondylitis (spinal arthritis).

If you have a family member with fibromyalgia, you may be more likely to get fibromyalgia.

The cause of fibromyalgia remains unknown, but recent advances and discoveries have helped to unravel some of the mysteries of this disease. Research highlights some of the biochemical, metabolic, and immunoregulatory abnormalities associated with fibromyalgia.

In fibromyalgia, there appears to a problem with the processing of pain in the brain. Patients often become hypersensitive to the perception of pain. The constant hypervigilance of pain is also associated with numerous psychological issues. Abnormalities noted in fibromyalgia include 14:

- Elevated levels of the excitatory neurotransmitters like glutamate and substance P

- Diminished levels of serotonin and norepinephrine in the descending anti-nociceptive pathways in the spinal cord

- Prolonged enhancement of pain sensations

- Dysregulation of dopamine

- Alteration in the activity of brain endogenous opioids.

Management of fibromyalgia syndrome at the present time is very difficult as it has multiple etiological factors and psychological predispositions; however, a patient centered approach is essential to handle this problem.

If you think you have fibromyalgia, visit your doctor. Treatment is available to ease some of its symptoms, although they’re unlikely to disappear completely.

It’s important to have a health care team that understands fibromyalgia and has experience treating fibromyalgia. Your team will probably include your family doctor, a rheumatologist, and a physical therapist. Other health care professionals may help you manage other symptoms, such as mood or sleep problems. However, the most important member of your health care team is you. The more active you are in your care, the better you will feel.

There is no cure for fibromyalgia, but fibromyalgia can be effectively treated and managed with a variety of medications and self-care strategies. It’s important for you to be responsible for your health. Getting enough sleep, exercising, stress-reduction and eating well may also help. No one treatment works for all symptoms, but trying a variety of treatment strategies can have a cumulative effect.

Exercise seems to be the most effective treatment, including yoga, tai chi, or other low-impact aerobic activity. Acupuncture, chiropractic, and massage may help ease symptoms. Psychotherapy may help patients manage stress and anxiety. A sleep specialist may help patients address sleep disorders.

Medications can help reduce the pain of fibromyalgia and improve sleep. Three drugs are FDA-approved for fibromyalgia: Duloxetine (Cymbalta) and Milnacipran (Savella) adjust brain chemicals to ease widespread pain and fatigue associated with fibromyalgia and Pregabalin (Lyrica), which blocks overactive nerve cells involved in pain. Pregabalin (Lyrica) was the first drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat fibromyalgia.

- Pain relievers. Over-the-counter pain relievers such as acetaminophen (Tylenol, others), ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others) or naproxen sodium (Aleve, others) may be helpful. Opioid medications are not recommended, because they can lead to significant side effects and dependence and will worsen the pain over time.

- Older drugs, such as amitryptiline (Elavil), cyclobenzaprine (Flexeril) and other antidepressants may be used to help promote sleep. Opioids and sleep medicines like zolpidem (Ambien) are not recommended for use in treating fibromyalgia symptoms.

- Anti-seizure drugs. Medications designed to treat epilepsy are often useful in reducing certain types of pain. Gabapentin (Neurontin) is sometimes helpful in reducing fibromyalgia symptoms.

Self-care is critical in the management of fibromyalgia:

- Stress management. Develop a plan to avoid or limit overexertion and emotional stress. Allow yourself time each day to relax. That may mean learning how to say no without guilt. But try not to change your routine completely. People who quit work or drop all activity tend to do worse than do those who remain active. Try stress management techniques, such as deep-breathing exercises or meditation.

- Sleep hygiene. Because fatigue is one of the main components of fibromyalgia, getting good quality sleep is essential. In addition to allotting enough time for sleep, practice good sleep habits, such as going to bed and getting up at the same time each day and limiting daytime napping.

- Exercise regularly. At first, exercise may increase your pain. But doing it gradually and regularly often decreases symptoms. Appropriate exercises may include walking, swimming, biking and water aerobics. A physical therapist can help you develop a home exercise program. Stretching, good posture and relaxation exercises also are helpful.

- Pace yourself. Keep your activity on an even level. If you do too much on your good days, you may have more bad days. Moderation means not overdoing it on your good days, but likewise it means not self-limiting or doing too little on the days when symptoms flare.

- Maintain a healthy lifestyle. Eat healthy foods. Do not use tobacco products. Limit your caffeine intake. Do something that you find enjoyable and fulfilling every day.

Doctors usually treat fibromyalgia with a combination of treatments, which may include:

- Medications, including prescription drugs and over-the-counter pain relievers.

- Aerobic exercise and muscle strengthening exercise.

- Patient education classes, usually in primary care or community settings.

- Stress management techniques such as meditation, yoga, and massage.

- Good sleep habits to improve the quality of sleep.

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) to treat underlying depression. CBT is a type of talk therapy meant to change the way people act or think.

In addition to medical treatment, people can manage their fibromyalgia with the self-management strategies described below, which are proven to reduce pain and disability, so they can pursue the activities important to them.

Self-Management Resources:

- You can join a self-management education class, which helps people with arthritis or other conditions—including fibromyalgia—be more confident in how to control their symptoms, how to live well and understand how the condition affects their lives. You can find more info on Self-Management Resource Center here: https://www.selfmanagementresource.com/

- Chronic Disease Self-Management Program is an effective self-management education workshop for people with chronic health problems. The program specifically addresses arthritis, diabetes, lung and heart disease, but teaches skills useful for managing a variety of chronic diseases. This program was developed at Stanford University. Locate a Chronic Disease Self-Management Program in your area here: http://www.eblcprograms.org/evidence-based/map-of-programs/

However, there isn’t one treatment plan that works best for every person who has fibromyalgia. You’ll have to work with your care team to create a plan that’s right for you. After all, nobody knows more than you do about your feelings, your actions, and how your fibromyalgia symptoms affect you.

Figure 1. Fibromyalgia tender points

Footnote: The dots indicate the 18 tenderness points important for the diagnosis of fibromyalgia.

[Source 16 ]Is fibromyalgia real?

This is the top misconception where people think fibromyalgia isn’t a real medical problem or that it is “all in your head.” Despite there’s a lot that’s unknown about fibromyalgia, researchers have learned more about it in just the past few years.

In people who have fibromyalgia, the brain and spinal cord process pain signals differently. As a result, they react more strongly to touch and pressure, with a heightened sensitivity to pain. It is a real physiological and neurochemical problem.

The power of the mind is a real factor in pain perception. For example, studies have shown that anxiety that occurs in anticipation of pain is often more problematic than the pain experience itself. In that sense, the mind has a negative impact on symptoms. It takes lifestyle changes and small steps toward achieving wellness.

Why do I feel depressed?

Depression or anxiety may occur as a result of your constant pain and fatigue, or the frustration you feel with the condition. It is also possible that the same chemical imbalances in the brain that cause mood changes also contribute to fibromyalgia.

Does fibromyalgia cause permanent damage?

No. Although fibromyalgia causes symptoms that can be very painful and uncomfortable, your muscles and organs are not being damaged. Fibromyalgia is not life-threatening, but it is chronic (ongoing and lasting more than 3 months). Although there is no cure, there are many things you can do to feel better.

Is it hard to diagnose fibromyalgia?

Unfortunately, it can take years for some people who have fibromyalgia to get a correct diagnosis. This can happen for many reasons. The main symptoms of fibromyalgia are generalized muscle pain and fatigue. These are also common symptoms of many other health problems, such as chronic fatigue syndrome, hypothyroidism, and arthritis.

Currently, there is no laboratory test or X-ray that can diagnose fibromyalgia.

It may take some time for your doctor to understand all of your symptoms and rule out other health problems so he or she can make an accurate diagnosis. As part of this process, your family doctor may consult with a rheumatologist. This type of doctor specializes in pain in the joints and soft tissue.

Juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome

Juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome also called juvenile primary fibromyalgia syndrome, is a chronic condition characterized by symptoms of chronic diffuse musculoskeletal pain and multiple painful tender points on palpation 11. Juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome is often accompanied by fatigue, disorders of sleep, chronic headaches, irritable bowel syndrome, and subjective soft tissue swelling. The complexity of the presenting clinical picture in juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome has not been sufficiently defined in the literature 11. Similarities to adult fibromyalgia syndrome in juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome are often difficult to compare, because many of the symptoms are “medically unexplained” and often overlap frequently with other medical conditions. However, a valid diagnosis of juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome often decreases parents’ anxiety, reduces unnecessary further investigations, and provides a rational framework for a management plan. The diagnostic criteria proposed by Yunus and Masi in 1985 to define juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome were never validated or critically analyzed. In most cases, the clinical diagnosis is based on the history, the physical examination that demonstrates general tenderness (muscle, joints, tendons), the absence of other pathological conditions that could explain pain and fatigue, and the normal basic laboratory tests. Research and clinical observations defined that juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome may have a chronic course that impacts the functional status and the psychosocial development of children and adolescents.

The reported prevalence of juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome varies widely probably reflecting differences in ethnicity, socio-cultural background, psychological traits of the population and diverse methodologies that have been used in the published studies 17. The prevalence of juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome reported in the literature in different countries is summarized in Table 1. Juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome has a prevalence around 1-6%, more common in girls, and can be seen in children of all ages.

Table 1. Prevalence of juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome in children and adolescents: review of the literature

| References | Diagnostic criteria | Cohort variables | Country/prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buskila D, Press J, Gedalia A, Klein M, Neumann L, Boehm R, Sukenik S. Assessment of nonarticular tenderness and prevalence of fibromyalgia in children. J Rheumatol. 1993 Feb;20(2):368-70. | 1990 ACR criteria | 338 healthy school children, 179 boys and 159 girls, aged 9 to 15 yrs. | Israel Prevalence 6.2%. |

| Clark P, Burgos-Vargas R, Medina-Palma C, Lavielle P, Marina FF. Prevalence of fibromyalgia in children: a clinical study of Mexican children. J Rheumatol. 1998 Oct;25(10):2009-14. | 1990 ACR criteria. | 548 children, 264 boys and 284 girls, aged 9-15. | Mexico Prevalence 1.2%. |

| Mikkelsson M. One year outcome of preadolescents with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 1999 Mar;26(3):674-82. | Structured pain questionnaire to assess the prevalence and persistence of self-reported musculo-skeletal pain symptoms and disability caused by pain. | 1626 third and fifth grade schoolchildren | Finland Prevalence 1.3% at baseline. |

| Weir PT, Harlan GA, Nkoy FL, Jones SS, Hegmann KT, Gren LH, Lyon JL. The incidence of fibromyalgia and its associated comorbidities: a population-based retrospective cohort study based on International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision codes. J Clin Rheumatol. 2006 Jun;12(3):124-8. doi: 10.1097/01.rhu.0000221817.46231.18 | ICD-9 criteria (*) | 2595 incident cases of adult and juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome | U.S.A The estimated prevalence per age group was: 0.5 to1% for 0-4 yrs; 1 to 1.4% for 5-9 yrs; 2 to 2.6% for 10-14 yrs; and 3.5 to 6.2% for 15-19 yrs. |

| Fuda A et al. Egypt Rheumatol Rehabil 2014; 41: 135-138 | A questionnaire was completed by students. A clinical diagnosis of fibromyalgia was established in only 25 cases. | 2000 students: 960 boys (48%) and 1040 girls (52%). Ages: 9-15 yrs, mean 11.9 yrs | Egypt prevalence 1.2%. |

Abbreviations: JFMS = juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome; FM = fibromyalgia; (*) International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes to identify fibromyalgia cases (ICD code 729.1).

[Source 11 ]Juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome in children and adolescents treatments

Goals of treatment should be pain relief, restoration of functioning, reduction of school absenteeism, dissolving social isolation, strengthening self-awareness, mobilizing domestic resources and the development of strategies for coping with pain. The inclusion of the family, the training of strategies in everyday life and the treatment of mental comorbidities are also important 18.

Evidence-based treatment guidelines in ibromyalgia include those developed by the American Pain Society (APS) in 2005 19 and the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) in 2008 20.

However, they were developed before FDA approved any medications for treating fibromyalgia and substantial heterogeneity exists between the recommendations. Furthermore, the studies evaluated during the development of these guidelines were not directly comparable as a result of variations in study design and short duration that limit their general applicability in clinical practice 21.

Little is known regarding treatment choices of youth diagnosed with juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome as they move into young adulthood. The management of juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome is centered on the issues of education, behavioral and cognitive change (cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT]) with a strong emphasis on physical exercise), and a relatively minor role for pharmacological treatment with medications such as muscle relaxants, analgesics and tricyclic agents 22. Any patient being treated with a medication should be carefully evaluated for both efficacy as well as side effects, and medications should be discontinued unless there is evidence for definite benefit. More controlled studies are needed to investigate the effectiveness of these complementary methods to assist treatment providers in giving evidence-based treatment recommendations.

A recent Cochrane review has concluded that psychological treatments may improve pain control for children with a variety of pain conditions, including muscle pain, abdominal pain, headaches and fibromyalgia syndrome 23. Therefore, it appears that CBT should be offered as a preferred modality of non-pharmacological treatment for juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome.

If disease development is assumed to be linked to the family background, hospitalization aimed to temporarily isolate the patient from his or her home environment should be taken into consideration 24.

Prompt recognition of juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome may decrease problems for pediatric patients with chronic pain, while pediatric primary care providers’ lack of familiarity with juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome can cause a delay in diagnosis and management 25.

Fibromyalgia in children and adolescents prognosis

Initial studies indicated a positive long-term prognosis for juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome 26. By contrast, studies in subjects with juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome recruited from hospital settings have shown a chronic and fluctuating course, with symptoms persisting in ~70% of young people 27.

One controlled study published in 2010 of patients with juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome and matched healthy controls (mean age, 15 years) showed that about 50% of patients with juvenile fibromyalgia met the full American College of Rheumatology criteria for fibromyalgia at ~4 years follow-up (mean age, 19 years), and >70% had continuing symptoms of pain, fatigue or sleep difficulty 27.

Several authors report different prognoses between adults and youths with fibromyalgia 28. They suggested that the early detection of juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome is an indication of a better prognosis 29, with significant gains in quality of life 30, and functionality for individuals who receive adequate treatment, whereas those with widespread pain that are not treated adequately have a greater chance of developing fibromyalgia 31. On the other hand, in a large prospective longitudinal study of juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome patients, Kashikar-Zuck et al. 32 found that the majority of adolescent patients (~80%) with juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome seen in a pediatric specialty care setting continued to report persistent pain and other FM symptoms as they transitioned into young adulthood.

In conclusion, most of youth with juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome continue to experience symptoms into adulthood, which highlights the importance of early diagnosis and intervention. However, more research into the variability of outcomes within the juvenile primary fibromyalgia syndrome group, with closer examination of risk and protective factors associated with future outcomes is essential to designing focused interventions.

Fibromyalgia syndrome causes

The exact cause of fibromyalgia is unknown, but fibromyalgia is thought to be related to abnormal levels of certain chemicals in the brain and changes in the way the central nervous system (brain, spinal cord and nerves) processes pain messages carried around the body 33, 34, 35. Current evidence describes fibromyalgia pain as the result of a complex evaluative process of environmental and multisystem information 36, 37. For this reason, currently, pain is considered a personal somatic experience in response to a threat to bodily or existential integrity 38. Pain and sensory processing alterations in the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) are present in fibromyalgia 35. Patients perceive noxious stimuli as being painful at lower levels of physical stimulation compared to healthy controls 39. With rapidly repetitive short noxious stimuli to fibromyalgia patients, they experience higher than normal increases in the perceived intensity of pain. There appears to be a deficiency in the endogenous analgesic systems in patients with fibromyalgia. There has been a demonstration of differences in activation of areas of the brain which are pain-sensitive areas by functional neuroimaging techniques 40.

There is no evidence of any single event cause of fibromyalgia syndrome; instead, it is triggered or aggravated by multiple physical and/or emotional stressors which include infections as well as emotional and physical trauma 40.

It’s also suggested that some people are more likely to develop fibromyalgia because of genes inherited from their parents, though there is no documentation of a definitive candidate gene 41.

There is most often some triggering factor that sets off fibromyalgia. It may be spine problems, arthritis, injury, or other type of physical stress. Emotional stress also may trigger fibromyalgia. The result is a change in the way your body “talks” with your spinal cord and brain. Levels of brain chemicals and proteins may change. More recently, fibromyalgia has been described as Central Pain Amplification disorder, meaning the volume of pain sensation in the brain is turned up too high.

In many cases, fibromyalgia appears to be triggered by a physically or emotionally stressful event, such as:

- an injury or infection

- giving birth

- having an operation

- the breakdown of a relationship

- the death of a loved one

- illness or other diseases

- post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- repetitive injuries

- obesity.

Here are some of the main factors thought to contribute to fibromyalgia:

Abnormal pain messages

One of the main theories is that people with fibromyalgia have developed changes in the way the central nervous system processes the pain messages carried around the body. This could be due to changes to chemicals in the nervous system.

The central nervous system (brain, spinal cord and nerves) transmits information all over your body through a network of specialized cells. Changes in the way this system works may explain why fibromyalgia results in constant feelings of, and extreme sensitivity to, pain.

Chemical imbalances

Research has found that people with fibromyalgia have abnormally low levels of the hormones serotonin, noradrenaline and dopamine in their brains.

Low levels of these hormones may be a key factor in the cause of fibromyalgia, as they’re important in regulating things such as:

- mood

- appetite

- sleep

- behavior

- your response to stressful situations

These hormones also play a role in processing pain messages sent by the nerves. Increasing the hormone levels with medication can disrupt these signals.

Some researchers have also suggested that changes in the levels of some other hormones, such as cortisol (which is released when the body is under stress), may contribute to fibromyalgia.

Sleep problems

It’s possible that disturbed sleep patterns may be a cause of fibromyalgia, rather than just a symptom.

Fibromyalgia can prevent you from sleeping deeply and cause fatigue (extreme tiredness). People with the condition who sleep badly can also have higher levels of pain, suggesting that these sleep problems contribute to the other symptoms of fibromyalgia.

Genetics

Research has suggested that genetics may play a small part in the development of fibromyalgia, with some people perhaps more likely than others to develop the condition because of their genes, although there is no evidence of a definitive gene has been found 41. Currently, about 100 genes that regulate pain are believed to be relevant to pain sensitivity or analgesia. The main genes are those encoding for voltage-dependent sodium channels, GABAergic pathway proteins, mu-opioid receptors, catechol-O-methyltransferase and GTP cyclohydrolase 1 42. Further studies are needed to understand the role of these genes in chronic pain conditions such as fibromyalgia.

Associated conditions

There are several other conditions often associated with fibromyalgia. Generally, these are rheumatic conditions (affecting the joints, muscles and bones), such as:

- Osteoarthritis – when damage to the joints causes pain and stiffness

- Lupus – when the immune system mistakenly attacks healthy cells and tissues in various parts of the body

- Rheumatoid arthritis – when the immune system mistakenly attacks healthy cells in the joints, causing pain and swelling

- Ankylosing spondylitis – pain and swelling in parts of the spine

- Temporomandibular disorder – a condition that can cause pain in the jaw, cheeks, ears and temples

Conditions such as these are usually tested for when diagnosing fibromyalgia.

Possible triggers

Fibromyalgia is often triggered by a stressful event, including physical stress or emotional (psychological) stress. Possible triggers for the condition include:

- an injury

- a viral infection

- giving birth

- having an operation

- the breakdown of a relationship

- being in an abusive relationship

- the death of a loved one

However, in some cases, fibromyalgia doesn’t develop after any obvious trigger.

Risk factors for fibromyalgia

Known risk factors for fibromyalgia include:

- Age. Fibromyalgia can affect people of all ages, including children. However, most people are diagnosed during middle age and you are more likely to have fibromyalgia as you get older.

- Lupus or Rheumatoid Arthritis. If you have lupus or rheumatoid arthritis (RA), you are more likely to develop fibromyalgia.

Some other factors have been weakly associated with onset of fibromyalgia, but more research is needed to see if they are real. These possible risk factors include:

- Sex. Women are seven times as likely to have fibromyalgia as men.

- Stressful or traumatic events, such as car accidents, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

- Repetitive injuries. Injury from repetitive stress on a joint, such as frequent knee bending.

- Illness (such as viral infections).

- Family history. You may be more likely to develop fibromyalgia if a parent or sibling also has fibromyalgia.

- Obesity.

Fibromyalgia syndrome pathophysiology

Fibromyalgia appears to be related to a pain-processing problem in your brain 43, 44, 16. In most cases, people with fibromyalgia become hypersensitive to the perception of pain 16. The constant hypervigilance to pain can also be associated with psychological problems 43.

Abnormalities noted in fibromyalgia include 43:

- Elevated levels of the excitatory neurotransmitters like glutamate and substance P

- Diminished levels of serotonin and norepinephrine (also known as noradrenaline) in the descending anti-nociceptive pathways in the spinal cord

- Prolonged enhancement of pain sensations

- Dysregulation of dopamine

- Alteration in the activity of brain endogenous opioids.

Fibromyalgia is more common in women than men because of the following 43:

- Higher levels of anxiety

- Use of maladaptive coping methods

- Altered behavior in response to pain

- Higher levels of depression

- Altered input to the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord)

- Hormonal effects of the menstrual cycle

The main alterations observed in fibromyalgia are dysfunctions in mono-aminergic neurotransmission, leading to elevated levels of excitatory neurotransmitters, such as glutamate and substance P, and decreased levels of serotonin and norepinephrine in the spinal cord at the level of descending anti-nociceptive pathways. Other anomalies observed are dopamine dysregulation and altered activity of endogenous cerebral opioids. Taken together, these phenomena seem to explain the central physiopathology of fibromyalgia 45.

Over the years, peripheral pain generators have also been recognized as a possible cause of fibromyalgia. In this case, patients manifest symptoms such as cognitive impairment (“fibro-fog”), chronic fatigue, sleep disturbances, intestinal irritability, interstitial cystitis and mood disorders 46, 47.

Peripheral abnormalities may contribute to increased nociceptive tonic supply in the spinal cord, which results in central sensitization. Other factors that appear to be involved in the pathophysiology of fibromyalgia are neuroendocrine factors, genetic predisposition, oxidative stress and environmental and psychosocial changes 48, 49.

Pain-processing problem in the brain

Fibromyalgia appears to be related to a pain-processing problem in your brain also known as central sensitization 43, 44, 16. In most cases, people with fibromyalgia become hypersensitive to the perception of pain 16. Central sensitization refers to a neuronal signal amplification mechanism within the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) that leads to a greater perception of pain 50. For this reason, patients with fibromyalgia present an increase in the receptive field of pain, allodynia and hyperalgesia. Central sensitization is also implicated in persistent and chronic pain. Although central sensitization plays an important role in fibromyalgia, it is even more important to understand the initial cause, that is, the persistent nociceptive input associated with tissue damage, including peripheral sensitization 51. According to Vierck 51, if peripheral pain generators can be blocked, the symptoms of fibromyalgia should disappear or not even develop. Despite this, researchers focus more on central sensitization as the mechanism of pain sensitivity because there is less evidence to support the involvement of peripheral pain tissue abnormalities and nociceptive processes in fibromyalgia 52. Brosschot et al. 53 observed that fibromyalgia patients were selectively attentive to information regarding the body and the environment in relation to pain. In this regard, they introduced the term “cognitive-emotional sensitization” to explain how selective attention to certain body pain can increase the perception of that pain. Pain sensitivity is also linked to social groups. It has been suggested that the mechanism that underlies “interpersonal sensitization” could be linked to the shared neuronal representation of the experience of pain. In other words, a feed-forward effect occurs in which a family, in an attempt to reduce painful behaviors in one of its members, actually creates a state of anxiety in the person concerned by increasing the perception of pain 54, 55.

Patients with fibromyalgia present a lower pain threshold that generates a condition of diffuse hyperalgesia and/or allodynia. This indicates that there may be a problem with the amplification of pain or with sensory processing in the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord). These fibromyalgia phenomena have been confirmed in clinical studies that used functional neuroimaging or measured alterations in neurotransmitter levels that influence sensory transmission and pain 56, 57, 58. It was also observed that treatments with drugs aimed at increasing anti-nociceptive neurotransmitters in the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) or at lowering the levels of pro-nociceptive excitatory neurotransmitters, such as glutamate, were able to improve these conditions in patients with fibromyalgia. Exercise has also proved useful for increasing anti-nociceptive neurotransmitters and reducing glutamate 59, 60. In contrast, patients with fibromyalgia do not respond to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) therapies aimed at resolving acute pain or pain induced by tissue damage or inflammation.

The chronic pain typical of fibromyalgia is due to alterations in central and peripheral sensitization. Over the years, researchers have searched for biomarkers that are capable of detecting these changes. In particular, they focused on factors capable of acting on the growth and survival of nerve cells, such as nerve growth factor (NGF). The nerve growth factor (NGF) is indeed involved in promoting the growth, proliferation and survival of sensory neurons that transmit pain, temperature and tactile sensations 61. Data obtained in earlier studies showed an increase in nerve growth factor (NGF) in the cerebrospinal fluid of fibromyalgia patients 62. However, these data disagree with those from a recent study in patients, in which plasma NGF levels were not found to differ between fibromyalgia and control subjects. In this regard, different statistical methods were used, which nonetheless led to the same conclusions 63. Further studies are therefore needed to understand the involvement of NGF in the pathophysiology of fibromyalgia.

Inflammation and Immunity

Increasing evidence indicates that neurogenic-derived inflammatory processes occurring in the peripheral tissues, spinal cord and brain are also responsible for the pathophysiology of fibromyalgia 64, 65, 66. The release of biologically active agents, such as chemokines and cytokines, leads to the activation of the innate and adaptive immune system. All of this translates into many of the peripheral clinical features reported by patients with fibromyalgia, such as swelling and dysesthesia, which can also affect central symptoms, including cognitive changes and fatigue. In addition, the physiological mechanisms related to stress and emotions are considered to be upstream drivers of neurogenic inflammation in fibromyalgia 67.

Studies conducted in patients have confirmed that inflammation is involved in fibromyalgia. Fibromyalgia patients have been shown to have enhanced circulating inflammatory cytokines and inflammatory cytokines released by circulating immune cells 66, 68.

Kadetoff et al. 69 described an increased concentration of IL-8 in the cerebrospinal fluid of fibromyalgia patients compared to healthy subjects. This finding could be due to the activation of glial cells, which play an important role in the central sensitization process, as they are activated in response to excitatory synaptic signals (glutamate) 70. Furthermore, since the synthesis of IL-8 is dependent on orthosympathetic activation, this could help explain the correlation between stress and fibromyalgia symptoms 71. In addition to this, some studies have shown an increase in serum concentrations of IL-6, IL-8, IL-1β and TNF-α in individuals with fibromyalgia, although no clear correlation with symptom severity has been identified, except, perhaps, for IL-6 66, 72, 73, 74. It appears that immune cells such as mast cells, monocytes and neutrophils, as mediators of inflammation processes, may also have a function in defining an inflammatory substrate of fibromyalgia 75. In animals, macrophages located in the muscle have been shown to contribute to the development of chronic widespread muscle pain. For example, the removal of macrophages at the acid injection site through a local injection of clodronate liposomes is capable of preventing the development of exercise-induced hyperalgesia 76. Another observation is that pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukins (IL-1β, IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor (TNFα), can activate and sensitize nociceptors, induce pain in humans and trigger hyperalgesia in animals. Another potential source of these cytokines is adipose tissue; many studies suggest that diffuse or multifocal pain is more common in obese individuals 77 and obese animals show enhanced nociceptive responses 78, 79. Therefore, pro-inflammatory cytokines could play a role in the generation of chronic muscle pain, including fibromyalgia.

Smart et al. 80 described a subgroup of fibromyalgia patients characterized by ANA (anti-nuclear antibody) positivity, with the speckled pattern clearly predominating. The use of the Smart Index, which corrects the erythrocyte sedimentation rate value in relation to age, revealed that ANA-positive fibromyalgia patients had a more pronounced inflammatory response profile than the ANA-negative subgroup, suggesting that autoimmunity potentially contributes to sub-inflammatory fibromyalgia 80.

Genetic factors

Over the years, studies have shown the potential involvement of genetic factors in the onset of fibromyalgia 81, 82. Linkage studies have shown a correlation rate of 50% between genetic variants and the development of chronic pain 83. Currently, about 100 genes that regulate pain are believed to be relevant to pain sensitivity or analgesia. The main genes are those encoding for voltage-dependent sodium channels, GABAergic pathway proteins, mu-opioid receptors, catechol-O-methyltransferase and GTP cyclohydrolase 1 42. The small sample sizes did not allow the authors to confirm an association between single nucleotide polymorphisms and fibromyalgia susceptibility. However, a genome-wide linkage scan study found that first-degree relatives had an increased risk of developing fibromyalgia, reinforcing the genetic hypothesis. The serotonin transporter gene (SLC64A4) and the transient receptor 2 potential vanillic channel gene (TRPV2) are the major genes responsible for pain susceptibility in fibromyalgia 84. SLC64A4 is characterized by a single nucleotide polymorphism and is associated with chronic pain conditions (for example, mandibular joint disorder), as well as increased levels of depression and psychological disorders related to an alteration in serotonin reuptake 85. The TRPV2 gene is expressed in mechano- and thermo-responsive neurons in the dorsal root and trigeminal ganglia and appears to be responsible for reducing the pain threshold in fibromyalgia patients 86.

Other genetic polymorphisms that have been identified and associated with fibromyalgia susceptibility are in the serotonin transporter (5-HTT), catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) and serotonin 2A (5-HT2A) genes. However, subsequent meta-analyses could only confirm that the 102T/C polymorphism in the 5-HT2A receptor is connected with fibromyalgia 87. Therefore, further studies are needed to understand the role of these genes in chronic pain conditions such as fibromyalgia. A genome-wide association and copy number variant study in 952 fibromyalgia cases and 644 controls revealed the existence of two variables associated with fibromyalgia. One variable is the single nucleotide polymorphism rs11127292 in a gene similar to myelin transcription factor 1 (MYT1L), which is responsible for neuronal differentiation and involved in cognitive alterations. The second is an intron copy number variable in the neurexin 3 (NRXN3) gene, which normally acts as a receptor and cell adhesion molecule in the nervous system, and variations in this gene are involved in autism spectrum disorder 88.

Other researchers analyzed 350 other genes that are specifically involved in pain treatment. Among these is the TAAR1 gene, which mediates the availability of dopamine, whose reduction can increase the sensitivity to pain typical of fibromyalgia 89. Another widely studied gene is RGS4, which is expressed in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, the locus coeruleus and the nuclei of the bed of the stria terminalis, and is responsible for modulating the descending inhibition of pain perception 90. One gene studied and related to pain disorders is CNR1, which encodes the cannabinoid receptor CB-1 91, 92. Another gene presumably involved in central sensitization is GRIA4, which mediates the rapid excitatory transmission of nociceptive signals in the central nervous system 93. Taken together, these studies have increased the current knowledge on fibromyalgia and support genes as a potential factor in the pathogenesis of this disease. However, as fibromyalgia remains a multifactorial disease, further studies are needed to examine haplotypes and combinations of different variants that could influence its development.

Endocrine factors

The role of stress in the worsening of fibromyalgia symptoms has been widely described from an epidemiological point of view through both self-reports and clinical questionnaires. On the basis of these data, the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, central to the stress response, was examined. Despite the discrepancy between different studies on possible alterations in plasma cortisol levels in fibromyalgia patients, dysregulation of its circadian variation is frequently observed. In particular, flattening of the plasma cortisol concentration curve was observed during the day: this seems to manifest itself through a milder and more gradual descent compared to the morning peak of maximum concentration or through a lowering of the peak itself 94, 95, 96, 97, 98. In addition to this, decreased cortisol secretion has also been described in response to adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) tests 99. The hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis (HPA) comprises neurotransmitter and neuroendocrine response systems to stress and can be activated in fibromyalgia 100. This system may explain some of the symptoms seen in fibromyalgia.

A patient study looked at levels of corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), heart rate variability (HRV) and pain symptoms (e.g., fatigue and depression) in subjects with fibromyalgia. The results obtained in this study showed that corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) levels were associated with sensory and affective pain symptoms but not with symptoms of fatigue. Furthermore, an increase in heart rate variability (HRV) was associated with an increase in CRF and pain in patients with fibromyalgia. These results were subsequently adjusted for age, sex and depressive symptoms, and a correlation between CRF levels and sensory pain symptoms was confirmed. Another important finding was that women with fibromyalgia and self-reported histories of physical or sexual abuse did not have increased levels of CRF in their CSF. This indicates that there may be subgroups of fibromyalgia patients with different neurobiological characteristics. Therefore, further studies are needed to better understand the association between CRF and pain symptoms in fibromyalgia 101. In another study, the association between salivary cortisol levels and pain symptoms in patients with fibromyalgia was assessed at different times of day. The results obtained in this study revealed a strong relationship between salivary cortisol and pain symptoms only at the time of awakening and the 1 h that followed in women with fibromyalgia. Furthermore, no relationship was observed between the cortisol level and symptoms of fatigue or stress. These findings suggest that early-day pain symptoms are associated with changes in hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis (HPA) function in women with fibromyalgia.

However, to date, the results regarding the involvement of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis (HPA) in the pathophysiology of fibromyalgia have been conflicting, and new studies will be needed in the future to fully clarify this aspect 96. Furthermore, there are indications that total and free cortisol levels are dissociated in fibromyalgia patients. They have normal salivary and free plasma cortisol despite having reduced total cortisol levels. A possible explanation for this finding is a reduced concentration of glucocorticoid-binding globulin (CBG). Reduced levels of glucocorticoid-binding globulin have been reported in fibromyalgia patients compared to healthy patients. It is of particular interest that chronic social stress can lead to reduced levels of glucocorticoid-binding globulin, while IL-6 and IL-1β, which can also inhibit glucocorticoid-binding globulin production, may contribute further 102.

The possible pathogenetic role of the growth hormone (GH)/insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) axis was also investigated. Several studies have found that about one-third of individuals with fibromyalgia have lower IGF-1 levels than control groups 103. Serial measurements at 12 to 24 h also showed a reduction in growth hormone (GH) secretion in patients with fibromyalgia, particularly at night. Since GH secretion occurs mainly during phase 3 of sleep and 80% of patients have sleep disturbances, it remains to be clarified whether the nature of this alteration is primary or secondary 104. Given the higher prevalence of fibromyalgia in the female population, the role of estrogens in this pathology was investigated. However, the results of various studies suggest that this role is limited, and the only significant result is an increased serum concentration of the G protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER) in patients with fibromyalgia compared to healthy subjects 105. Although a strong correlation with the disease allows us to hypothesize the possible use of this receptor as a potential diagnostic biomarker, the exact mechanism by which it fits into the pathophysiological cascade remains unclear 106.

Psychopathological factors

Psychiatric comorbidities in fibromyalgia constitute a relevant aspect of the disease, and a close correlation between stress and fibromyalgia symptoms has been described several times. According to several studies, the prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities, such as anxiety disorders and depression, among patients with this pathology reaches 60% in certain subpopulations 107. The presence of depressive patterns has been shown to correlate with a worse prognosis: patients with comorbid symptoms of depression seem to report pain of greater severity and duration as well as a greater degree of hyperalgesia/allodynia than healthy controls. Furthermore, these psychiatric aspects seem to have a certain predictive value in relation to various somatic symptoms, including musculoskeletal pain and headaches 108. The impact of depression symptoms on pain processing is still unclear. A study in fibromyalgia patients attempted to evaluate this correlation by comparing the results of quantitative sensory tests and neuronal responses to pressure stimuli (assessed by functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI)) with the levels of symptoms of depression. The results showed that the symptom levels of depression were not associated with quantitative test results or with the extent of neuronal activation in brain areas, such as primary and secondary somatosensory cortices, that are associated with the sensory dimension of pain. However, symptoms of depression were observed to be associated with the extent of pain-evoked neuronal activation in the amygdala and contralateral anterior insula, which are brain areas associated with affective pain processing. Therefore, these findings suggest the existence of parallel, possibly independent, neuronal pain processing networks for sensory and affective pain elements 109.

The therapeutic aspect is an element that supports the pathogenetic overlap between depressive disorder and fibromyalgia. The effectiveness of treatment with antidepressant drugs (e.g., serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) and tricyclics) has in fact been described by numerous studies on fibromyalgia patients and constitutes one of the main therapeutic strategies in both fibromyalgia and other chronic pain conditions, such as chronic headache and irritable bowel (IBS), which are often symptoms of fibromyalgia 110, 111, 112. The effectiveness of serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) and other double-acting antidepressants, such as mirtazapine, suggests that neurotransmission dysfunction of both serotonin and norepinephrine exists in fibromyalgia 113. Similar to observations for the depressive pattern, stress also appears to be both a predictive and negative prognostic factor. It has been shown that stress can modulate pain sensitivity by inducing hyperalgesia or allodynia through alterations in the physiological circadian secretion of cholesterol, therefore indirectly inducing the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and setting in motion the pathophysiological processes described above 114, 115, 116.

Animal studies have shown that stress induction (e.g., swimming stress and cold stress) can produce muscle and skin hyperalgesia that lasts for weeks after the stressor 117, 118, 119. On the other hand, milder stressors (e.g., fatigue and acoustic stress), which do not produce hyperalgesia on their own, can cause an increase in and prolongation of the hyperalgesic response to a subthreshold or mild noxious stimulus 120, 121, 122. Other studies have shown that animals exposed to stressors also exhibit changes in the spinal cord. In particular, animals showed a greater expression of c-fos in response to formalin, as well as a reduction in the basal and induced release of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA; a reduction in mu-opioid agonist antinociception enhanced the basal and evoked the release of glutamate 123, 124, suggesting both increased central excitability and reduced central inhibition. In animals, stress-induced hyperalgesia was reduced by the spinal blockade of substance P, calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), NMDA-glutamate receptors and neurokinin-1 receptors, all substances involved in the neurotransmission of pain 122. At the supraspinal level, cold stress-induced alterations were observed in the serotonergic system, with reductions in both serotonin (5-HT) and 5-hydroxy indoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) levels in the supraspinal regions 125. Therefore, stress and psychological factors are involved in the development and severity of fibromyalgia.

Poor Sleep

Sleep disorders are classically described within the symptomatic process of fibromyalgia. However, some recently reported data have generated the hypothesis that sleep disorders may be included among the causative factors of this pathology, rather than among its manifestations. Studies published in recent years have described a bidirectional correlation between sleep disturbances and widespread musculoskeletal pain, and it even seems that insomnia tends to precede the onset of pain and has predictive value regarding its onset and its persistence 126, 127. Studies carried out in healthy subjects also seem to show that total, partial and stage-specific sleep deprivation leads to hyperalgesia, an increased incidence of spontaneous pain and mood alterations, particularly anxiety and depression 128, 129. In a further study by Smith et al. 130, the authors hypothesized that the development or aggravation of somatic and psychiatric symptoms is secondary to sleep discontinuity rather than sleep deprivation. In addition to the number of awakenings, the cyclic alternating pattern (CAP) is a useful tool to analyze this discontinuity. It is represented by short cycles of periodic electroencephalographic activity of non-REM sleep, distinct from the background rhythm and with a periodicity of up to one minute 131. The cyclic alternating pattern (CAP) has been shown to be frequent in fibromyalgia patients and correlated with poor quality of sleep and with the severity of pain observed in these patients 132.

Findings in human studies carried out through the application of evoked potentials indicate that increased nociceptive sensitivity in response to sleep deprivation could derive from dysregulation of the descending pathways of pain control or from cognitive amplification of the central origin, thus excluding the mechanism of sensory amplification 133. Biochemical analyses suggest that an insufficient amount of sleep could also play a facilitating role in nociception through the elevation of the serum concentration of IL-6, thus entering the pathogenetic cascade with an inflammatory substrate 128. The structural analysis of sleep obtained by EEG studies provides additional support for the hypothesis that sleep alterations are among the causative factors of fibromyalgia. One of the first works on this aspect was a study by Moldofsky et al. 134, in which microstructural analysis identified the presence of a rhythm component typical of wakefulness within the non-REM sleep pattern, particularly during periods of slow delta rhythm (0.5 to 2 Hz, characteristic of deep sleep), among both fibromyalgia patients and healthy subjects deprived of the deeper stages of alpha sleep (8 to 13 Hz). Moreover, in healthy subjects, deprivation was accompanied by a set of musculoskeletal and psychological symptoms similar to those chronically reported by patients. In light of these data, a hypothesis was put forward that considered fibromyalgia, then called fibrositis, to be a “non-restorative sleep syndrome”, in which an arousal mechanism (presumably responsible for the alpha component) interferes with non-REM sleep and its restorative function, consequently generating mood alterations and characteristic somatic disturbances. More recent human studies have described the mechanisms underlying alpha-delta sleep (ADS, the intrusion of alpha rhythms in the deep phases of sleep), highlighting the role played by the thalamus, which, in turn, is modulated by GABAergic and cholinergic afferents 135, 136. It has been observed that the alpha-delta sleep (ADS, the intrusion of alpha rhythms in the deep phases of sleep) phenomenon manifests itself in three different patterns: phasic (contemporary with delta activity), tonic (continuous throughout NREM sleep) and low alpha activity. Among these, the phasic pattern appears to be the most common among fibromyalgia patients and is the one that correlates most strongly with symptoms such as insomnia and pain 137.

It should be noted, however, that alpha-delta sleep is not an exclusive feature of fibromyalgia: it is also seen in a number of chronic pain syndromes and in some healthy individuals. Unlike alpha activity, the functional anatomical substrate of sleep spindles has been extensively studied. These are trains of electroencephalographic waves with a frequency between 12 and 16 Hz, lasting between 0.5 and 1.5 s and recurring every 3 to 10 s, and characteristic of non-REM (NREM) sleep, particularly the N2 stage of sleep (intermediate sleep). Sleep spindles are generated by the rhythmic firing of thalamic relay neurons, and their role is central in the induction and maintenance of NREM sleep, as well as in the gating mechanism through which transmission and the consequent cortical response to both internal and external stimuli are attenuated during sleep (control of arousal status) 138, 139, 140, 141. The frequency of spindles during NREM sleep is modulated by a series of factors, including age (inverse proportionality) and a certain degree of interindividual variability, as well as various pathological conditions in the neuropsychiatric field, such as depression, anxiety and stress 142. A study by Landis et al. 143 described a reduction in the frequency and amplitude of sleep spindles in a population of women with fibromyalgia compared to a control group, proposing the hypothesis of a dysfunction of the thalamo-cortical circuits underlying this alteration.

In a rat study 144, a deep learning method, known as SpindleNet, was applied to characterize sleep spindle activity in animals with induced chronic pain. The results showed a correlation between a decrease in the frequency of spindles during NREM sleep and the level of chronic pain and allodynia, suggesting that this finding could be a biomarker of chronic pain as well as a target for neuromodulator therapy 145. It is therefore possible to hypothesize that a dysfunctional primitive thalamus causes an alteration in its spindle pacemaker activity and alpha activity, compromising the restorative function of sleep and consequently generating the somatic and psychological symptoms of fibromyalgia, similar to what was suspected by Moldofsky et al 134. In light of the important function of the thalamus in sensory transmission pathways, it can also be hypothesized that both sleep disturbances and hyperalgesia/allodynia are the direct result of thalamic alteration, representing independent manifestations of the same pathological process. The relationship between sleep disturbances and fibromyalgia has not yet been fully clarified, and new studies will be needed to better define the relationship between the two. At the moment, the main hypotheses converge in their proposal of a bidirectional correlation characterized by a positive feedback circuit.

Fibromyalgia syndrome symptoms

Fibromyalgia has many symptoms that tend to vary from person to person. The main symptom is widespread pain. The pain associated with fibromyalgia often is described as a constant dull ache that has lasted for at least three months. To be considered ‘widespread pain’, the pain must occur on both sides of your body and above and below your waist.

Symptoms of fibromyalgia can include the following:

- Increased sensitivity to pain.

- Fatigue (extreme tiredness) or chronic fatigue syndrome

- A deep ache or a burning pain that gets worse because of activity, stress, weather changes, or other factors.

- Muscle stiffness or spasms.

- Pain that moves around your body.

- Feelings of numbness or tingling in your hands, arms, or legs.

- Feeling very tired or fatigued (out of energy), even when you get enough sleep. People with fibromyalgia often awaken tired, even though they report sleeping for long periods of time. Sleep is often disrupted by pain, and many patients with fibromyalgia have other sleep disorders, such as restless legs syndrome and sleep apnea.

- Trouble sleeping.

There may be periods when your symptoms get better or worse, depending on factors such as:

- your stress levels

- changes in the weather

- how physically active you are

People who have fibromyalgia often also have one or more of the following:

- Anxiety.

- Depression.

- Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

- Restless legs syndrome.

- Increased sensitivity to odors, bright lights, loud noises, or medicines.

- Headaches, migraines, or jaw pain.

- Dry eyes or mouth.

- Dizziness and problems with balance.

- Problems with memory or concentration (sometimes called the “fibro fog”).

- For women, painful menstrual periods.

If you think you have fibromyalgia, visit your doctor. Treatment is available to ease some of the symptoms, although it’s unlikely they’ll ever disappear completely.

The main symptoms of fibromyalgia are outlined below.

The 1990 American College of Rheumatology fibromyalgia classification criteria included tenderness at least 11 of 18 defined tender points:

- Suboccipital muscle insertion bilaterally

- The anterior aspect of C5 to C7 intertransverse spaces bilaterally

- Mid-upper border of trapezius bilaterally

- Origin of supraspinatus muscle bilaterally

- Second costochondral junctions bilaterally

- 2cm distal to the lateral epicondyles bilaterally

- Upper outer quadrants of buttocks bilaterally

- Greater trochanteric prominence bilaterally

- Medial fat pad of the knees bilaterally

The pressure appropriate for detecting these tender points should be equal 4 kg/cm², enough to whiten the nail bed of the fingertip of the examiner.

However, given many limitations of the tender point examination, the 2010 American College of Rheumatology diagnostic criteria eliminated these findings. The new American College of Rheumatology criteria are mentioned below under diagnosis.

Mood disturbances, including depression, anxiety and heightened somatic concern, may often also occur. Approximately 25% of fibromyalgia patients have accompanying depression at the time of diagnosis, while 50-75% of patients have a lifetime history of depression. In addition, the lifetime prevalence of an anxiety disorder in fibromyalgia patients is approximately 60% 146. The levels of depression and anxiety in patients with fibromyalgia seem to be associated with the degree of cognitive impairment, as shown in a meta-analysis of 23 case-control studies 147.

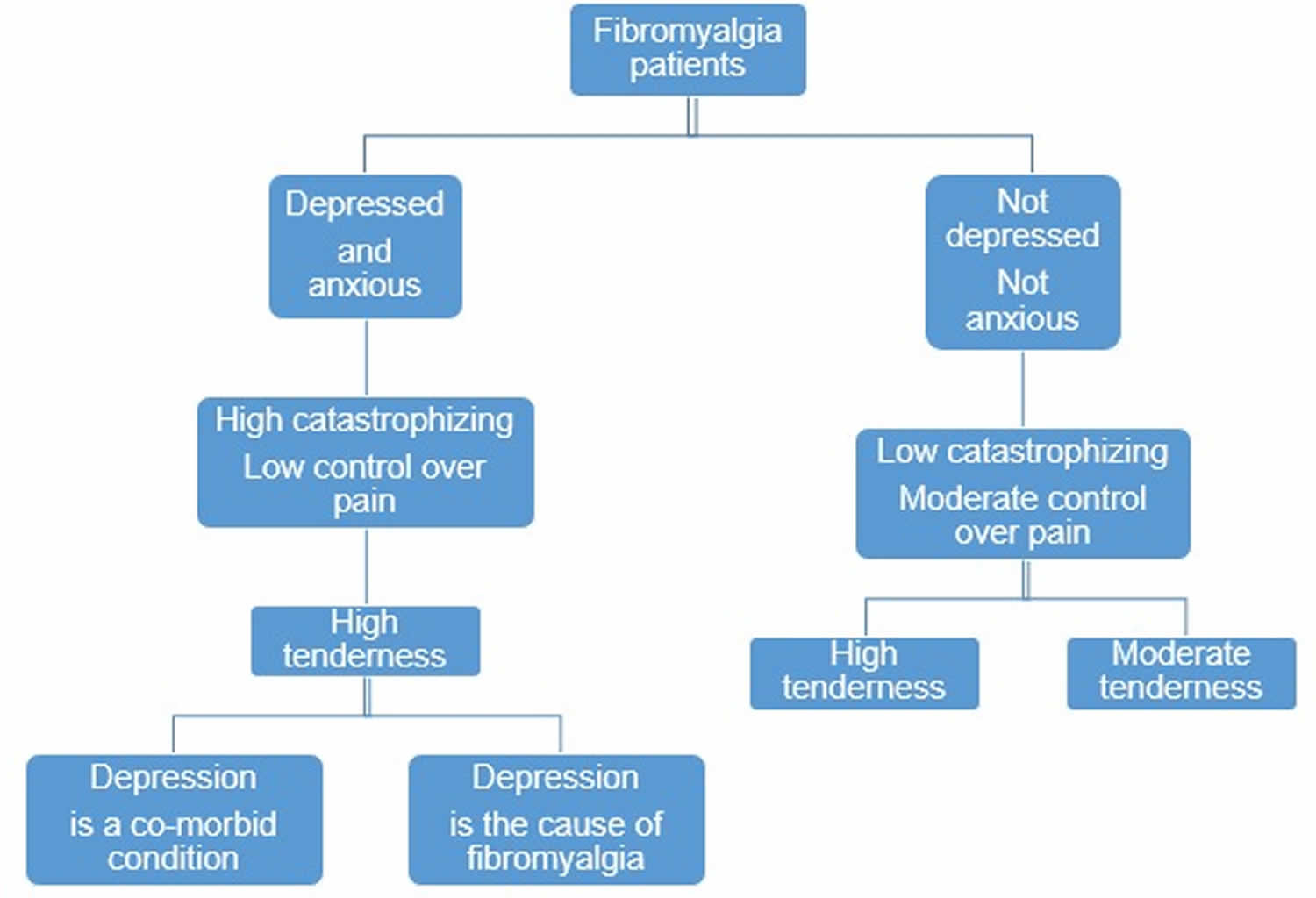

Based on the coexistence of depression and anxiety, fibromyalgia patients can be divided into 2 major groups. The first group comprises of patients without coexisting mood disorders, while the second of patients with concomitant depressive mood, often in combination with anxiety. According to the results of a study that intended to subgroup fibromyalgia patients based on: 1) mood status (evaluated by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale for depression and the State-Trait Personality Inventory for symptoms of trait-related anxiety), 2) cognition (by the catastrophizing and control of pain subscales of the Coping Strategies Questionnaire), and 3) hyperalgesia/tenderness (by dolorimetry and random pressure-pain applied at suprathreshold values), it was noted that fibromyalgia patients with depressive mood and anxiety are also ‘catastrophizing’. This term is used to indicate that such patients have a very negative, pessimistic view of what their pain is and what is causing, while they have no sense that they can control their pain. On the contrary fibromyalgia patients who are neither depressed nor anxious and therefore do not catastrophize, have a moderate sense that they can control their pain. These patients can be further divided into 2 subgroups based on the presence of hyperalgesia/tenderness as patients with high and lower levels of tenderness, (although they both fulfill the classification criteria for fibromyalgia) 148. In addition, it has been proposed that depressed fibromyalgia patients can also be divided into 2 subgroups, in the first one depression is a co-morbid condition, while in the second depression is the cause of fibromyalgia 149. All these fibromyalgia subgroups are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Fibromyalgia patient subgroups

In another study fibromyalgia patients were classified as dysfunctional, inter-personally distressed or adaptive coppers, based on their responses to the Multidimensional Pain Inventory. The dysfunctional patients experienced more pain behaviors and overt expressions of pain, distress, and suffering, such as slowed movement, bracing, limping, and grimacing compared to the inter-personally distressed or the adaptive coppers 150. It is of interest though that up to 25% of patients correctly diagnosed with a systemic rheumatic disease (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus) will also fulfill the classification criteria for fibromyalgia 151. The most commonly encountered comorbid conditions in fibromyalgia patients are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. The most commonly encountered co-morbid conditions in fibromyalgia

| Sleep disorders | Non restorative sleep (alpha-delta sleep anomaly) Sleep apnea Restless leg syndrome Nocturnal myoclonus |

|---|---|

| Chronic fatigue syndrome (systemic exertion intolerance disease) | |

| Psychiatric disorders | Anxiety disorders Depression Obsessive compulsive disorder |

| Headache | Tension type headache Migraine |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | |

| Musculofascial pain syndrome | Temporomandibular joint syndrome and interstitial cystitis |

| Dysmenorrhea | |

| Premenstrual syndrome | |

| Non-cardiac chest pain | |

| Raynaud’s phenomenon | |

| Systemic autoimmune diseases | Rheumatoid arthritis Systematic lupus erythematosus Sjögren’s syndrome Ankylosing spondylitis and other seronegative spondyloarthritis Polymyalgia rheumatica |

Widespread pain

If you have fibromyalgia, one of the main symptoms is likely to be widespread pain. This may be felt throughout your body, but could be worse in particular areas, such as your back or neck. The pain is likely to be continuous, although it may be better or more severe at different times.

The pain could feel like:

- an ache

- a burning sensation

- a sharp, stabbing pain

Temporo-mandibular joint pain (TMJ pain)

This Temporo-mandibular Joint Dysfunction Syndrome, sometimes referred to as TMJD, causes tremendous face and head pain in one quarter of fibromyalgia patients. However, a 1997 report indicates that as many as 90% of fibromyalgia patients may have jaw and facial tenderness that could produce, at least intermittently, symptoms of temporo-mandibular joint dysfunction. Most of the problems associated with this condition are thought to be related to the muscles and ligaments surrounding the joint and not necessarily the joint itself.

Extreme sensitivity

Fibromyalgia can make you extremely sensitive to pain all over your body, and you may find that even the slightest touch is painful. If you hurt yourself – such as stubbing your toe – the pain may continue for much longer than it normally would.

You may hear the condition described in the following medical terms:

- Hyperalgesia – when you’re extremely sensitive to pain

- Allodynia – when you feel pain from something that shouldn’t be painful at all, such as a very light touch

You may also be sensitive to things such as smoke, certain foods and bright lights. Being exposed to something you’re sensitive to can cause your other fibromyalgia symptoms to flare up.

Multiple Chemical Sensitivity Syndrome

Sensitivities to odors, noise, bright lights, medications and various foods is common in roughly 50% of fibromyalgia patients.

Stiffness

Fibromyalgia can make you feel stiff. The stiffness may be most severe when you’ve been in the same position for a long period of time – for example, when you first wake up in the morning.

It can also cause your muscles to spasm, which is when they contract (squeeze) tightly and painfully.

Fatigue

Fibromyalgia can cause fatigue (extreme tiredness). This can range from a mild, tired feeling to the exhaustion often experienced during a flu-like illness.

Severe fatigue may come on suddenly and can drain you of all your energy. If this happens, you may feel too tired to do anything at all.

Poor sleep quality

Fibromyalgia can affect your sleep. You may often wake up tired, even when you’ve had plenty of sleep. This is because the condition can sometimes prevent you from sleeping deeply enough to refresh you properly.

You may hear this described as “non-restorative sleep”.

Cognitive problems (‘fibro-fog’)

Cognitive problems commonly referred to as “fibro fog” are issues related to mental processes (cognitive difficulties), such as thinking and learning. If you have fibromyalgia, you may have:

- trouble remembering and learning new things

- problems with attention (the ability to focus) and concentration on mental tasks

- slowed or confused speech

Headaches

If fibromyalgia has caused you to experience pain and stiffness in your neck and shoulders, you may also have frequent headaches.

These can vary from being mild headaches to severe migraines, and could also involve other symptoms, such as nausea (feeling sick).

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

Some people with fibromyalgia also develop irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

IBS is a common digestive condition that causes pain and bloating in your stomach. It can also lead to constipation or diarrhoea.

Other symptoms

Other symptoms that people with fibromyalgia sometimes experience include:

- dizziness and clumsiness

- feeling too hot or too cold – this is because you’re not able to regulate your body temperature properly

- restless legs syndrome (an overwhelming urge to move your legs)

- tingling, numbness, prickling or burning sensations in your hands and feet (pins and needles, also known as paresthesia)

- in women, unusually painful periods

- anxiety

- depression

Depression

In some cases, having the condition can lead to depression. This is because fibromyalgia can be difficult to deal with, and low levels of certain hormones associated with the condition can make you prone to developing depression.

Depression can cause many symptoms, including:

- constantly feeling low

- feeling hopeless and helpless

- losing interest in the things you usually enjoy

If you think you may be depressed, it’s important to get help from your doctor or your fibromyalgia healthcare professional, if you’ve been seeing one.

Fibromyalgia syndrome complications

Fibromyalgia can cause pain, disability, and lower quality of life. US adults with fibromyalgia may have complications such as:

- More hospitalizations. If you have fibromyalgia you are twice as likely to be hospitalized as someone without fibromyalgia.

- Lower quality of life. Women with fibromyalgia may experience a lower quality of life.

- Higher rates of major depression. Adults with fibromyalgia are more than 3 times more likely to have major depression than adults without fibromyalgia. Screening and treatment for depression is extremely important.

- Higher death rates from suicide and injuries. Death rates from suicide and injuries are higher among fibromyalgia patients, but overall mortality among adults with fibromyalgia is similar to the general population.

- Higher rates of other rheumatic conditions. Fibromyalgia often co-occurs with other types of arthritis such as osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and ankylosing spondylitis.

Fibromyalgia syndrome diagnosis

If you think you have fibromyalgia, visit your doctor. Diagnosing fibromyalgia can be difficult, as there’s no specific test to diagnose the condition 153. And the symptoms of fibromyalgia, such as pain, sleep problems and fatigue, are common in many other conditions and can vary. It sometimes takes visits to several different health care providers to get a diagnosis.

During diagnosis, you’ll be asked about how your symptoms are affecting your daily life. If you have had any trouble sleeping or fatigue, tell your doctor how long you have had this problem. Your doctor may ask whether you have been feeling anxious or depressed since your symptoms began.

Your body will also be examined to check for visible signs of other conditions – for example, swollen joints may suggest arthritis, rather than fibromyalgia.

In the past, doctors would check 18 specific points on a person’s body to see how many of them were painful when pressed firmly (see Figure 1). Newer 2016 guidelines from the American College of Rheumatology don’t require a tender point exam. Instead, the main factor needed for a fibromyalgia diagnosis is widespread pain throughout your body for at least three months 154.

Fibromyalgia may now be diagnosed in adults when all of the following criteria are met 154:

- Generalized pain, defined as pain in at least 4 of 5 regions, is present.

- Symptoms have been present at a similar level for at least 3 months.

- Widespread pain index (WPI) ≥ 7 and symptom severity scale (SSS) score ≥ 5 OR WPI of 4–6 and SSS score ≥ 9.

- A diagnosis of fibromyalgia is valid irrespective of other diagnoses. A diagnosis of fibromyalgia does not exclude the presence of other clinically important illnesses.

To meet the American College of Rheumatology 2016 criteria, you must have pain in at least four of these five areas:

- Left upper region, including shoulder, arm or jaw

- Right upper region, including shoulder, arm or jaw

- Left lower region, including hip, buttock or leg

- Right lower region, including hip, buttock or leg

- Axial region, which includes neck, back, chest or abdomen.

Old guidelines required tender points

Fibromyalgia is also often characterized by additional pain when firm pressure is applied to specific areas of your body, called tender points. In the past, at least 11 of these 18 spots had to test positive for tenderness to diagnose fibromyalgia.

But fibromyalgia symptoms can come and go, so a person might have 11 tender spots one day but only eight tender spots on another day. And many family doctors were uncertain about how much pressure to apply during a tender point exam. While specialists or researchers may still use tender points, an alternative set of guidelines has been developed for doctors to use in general practice.

These newer diagnostic criteria include:

- Widespread pain lasting at least three months

- Presence of other symptoms such as fatigue, waking up tired and trouble thinking

- No other underlying condition that might be causing the symptoms.

Criteria for diagnosing fibromyalgia

1990 American College of Rheumatology classification criteria was used in many clinical and therapeutic trials but has not been useful in diagnosing fibromyalgia in clinical practice.

The 1990 American College of Rheumatology fibromyalgia classification criteria included:

- Symptoms of widespread pain, present on both sides of the body and both above and below the waist

- Physical findings of at minimum 11 of 18 defined tender points:

- Suboccipital muscle insertion bilaterally

- Anterior aspect of C5 to C7 intertransverse spaces bilaterally

- Mid upper border of trapezius bilaterally

- Origin of supraspinatus muscle bilaterally

- Second costochondral junctions bilaterally

- 2cm distal to the lateral epicondyles bilaterally

- Upper outer quadrants of buttocks bilaterally

- Greater trochanteric prominence bilaterally

- Medial fat pad of the knees bilaterally

The pressure appropriate for detecting these tender points should be equal to 4 kg/cm², enough to whiten the nail bed of the fingertip of the examiner.

For the purposes of classification, the patient is said to have fibromyalgia if both criteria are met.

There were a number of limitations of the 1990 1990 American College of Rheumatology diagnostic criteria, which include the following:

- Physicians do not know how to examine tender points, perform the exam incorrectly, or refuse to do so.

- A number of symptoms that were previously not considered were increasingly appreciated as key symptoms of fibromyalgia.

- The criteria set the bar so high that it left little room for variation among fibromyalgia patients. Also, the patient whose symptoms improved failed to satisfy the 1990 criteria.

Criteria Needed for a Fibromyalgia Diagnosis (American College of Rheumatology Fibromyalgia Diagnostic Criteria 2010) 155