Contents

- Gastritis

- Types of gastritis

- Gastritis symptoms

- Gastritis complications

- Cause of gastritis

- Gastritis prevention

- Gastritis diagnosis

- Gastritis treatment

- Gastritis diet

- Gastritis prognosis

Gastritis

Gastritis is a medical term for inflammation of the stomach lining that is histologically proven, sometimes with structural mucosal changes 1. Gastritis happens when your stomach lining, also known as the mucosa, becomes inflamed (swollen and red). The stomach lining may also erode (wear down) because of the inflammation, also known as erosive gastritis. Gastritis can happen suddenly and be short-lived (acute gastritis), or develop gradually and last over a few months or years (chronic gastritis). Acute gastritis will evolve to chronic, if not treated. Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is the most common cause of gastritis worldwide. Helicobacter pylori gastritis can cause problems absorbing iron from food. Drinking too much alcohol also can contribute to gastritis (alcohol gastritis). Autoimmune gastritis can cause problems absorbing iron and vitamin B12 from food. Pernicious anemia is a form of anemia that happens when your stomach is not able to digest vitamin B12. Common causes of pernicious anemia include atrophic gastritis and an autoimmune condition in which the body’s immune system attacks the actual intrinsic factor protein or the cells in the lining of your stomach that make it.

Other causes of gastritis include:

- having too much acid in the stomach

- acid reflux

- intense stress

- backflow of bile into the stomach (known as ‘bile reflux’)

- diabetes

- an infection with organisms other than H. pylori such as Mycobacterium avium intracellulare, Herpes simplex, and Cytomegalovirus.

- long-term use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as aspirin and over-the-counter pain and fever medicines

- diseases of the intestines or stomach, such as Crohn’s disease

- radiation to the stomach to treat cancer (known as ‘radiation gastritis’)

- an allergic reaction

- some cancer treatments

Rare causes of gastritis include collagenous gastritis, sarcoidosis, eosinophilic gastritis, and lymphocytic gastritis.

The majority of people with gastritis don’t have any symptoms. In some cases, gastritis cause symptoms of indigestion or of bleeding in the stomach.

Other symptoms of gastritis may include:

- a burning pain in the upper stomach area (such as in heartburn) — which may improve or worsen with eating

- acid reflux or gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

- nausea

- vomiting

- loss of appetite

- bloating and burping

- hiccups

- diarrhea

- feeling uncomfortably full after eating

- gurgling stomach and/or gas

- weight loss

- bad breath

- blood in the vomit or stools (poop)

To diagnose gastritis, your doctor may order an upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy with biopsies or other tests to diagnose gastritis, find the cause, and check for complications. Other tests may include blood, stool, and breath tests and an upper GI series.

While most gastritis can be mild and heal on its own, sometimes treatment may be needed, depending on the specific cause and type of gastritis you have. Treating gastritis can improve symptoms, if present, and lower your chance of complications. In some cases, gastritis can lead to ulcers and an increased your risk of stomach cancer.

Sometimes the symptoms of gastritis can be eased by eating and drinking in ways that don’t irritate the stomach. These include:

- Avoiding alcohol

- Avoiding foods that cause pain

- Avoid using non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) e.g., aspirin, ibuprofen and naproxen

- Eating smaller meals

However, sometimes medication is needed. Medication may be used to:

- Reduce the production of stomach acid:

- Acid blockers — also called histamine (H-2) blockers — reduce the amount of acid released into your digestive tract, which relieves gastritis pain and encourages healing. Available by prescription or over the counter, acid blockers include famotidine (Pepcid), cimetidine (Tagamet HB) and nizatidine (Axid AR).

- Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) reduce acid by blocking the action of the parts of cells that produce acid. These drugs include the prescription and over-the-counter medications omeprazole (Prilosec), lansoprazole (Prevacid), rabeprazole (Aciphex), pantoprazole (Protonix) and others. Long-term use of proton pump inhibitors, particularly at high doses, may increase your risk of hip, wrist and spine fractures. Ask your doctor whether a calcium supplement may reduce this risk.

- Make the stomach less acidic. Your doctor may include an antacid in your drug regimen. Antacids neutralize existing stomach acid and can provide rapid pain relief. Side effects can include constipation or diarrhea, depending on the main ingredients. These help with immediate symptom relief but are generally not used as a primary treatment. Proton pump inhibitors and acid blockers are more effective and have fewer side effects.

- Treat an infection with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), which is a common cause of gastritis. Your doctor may recommend a combination of antibiotics, such as clarithromycin (Biaxin XL) and amoxicillin (Amoxil, Augmentin, others) or metronidazole (Flagyl), to kill the bacterium. Be sure to take the full antibiotic prescription, usually for 7 to 14 days, along with medication to block acid production. Once treated, your doctor will retest you for H. pylori to be sure it has been destroyed.

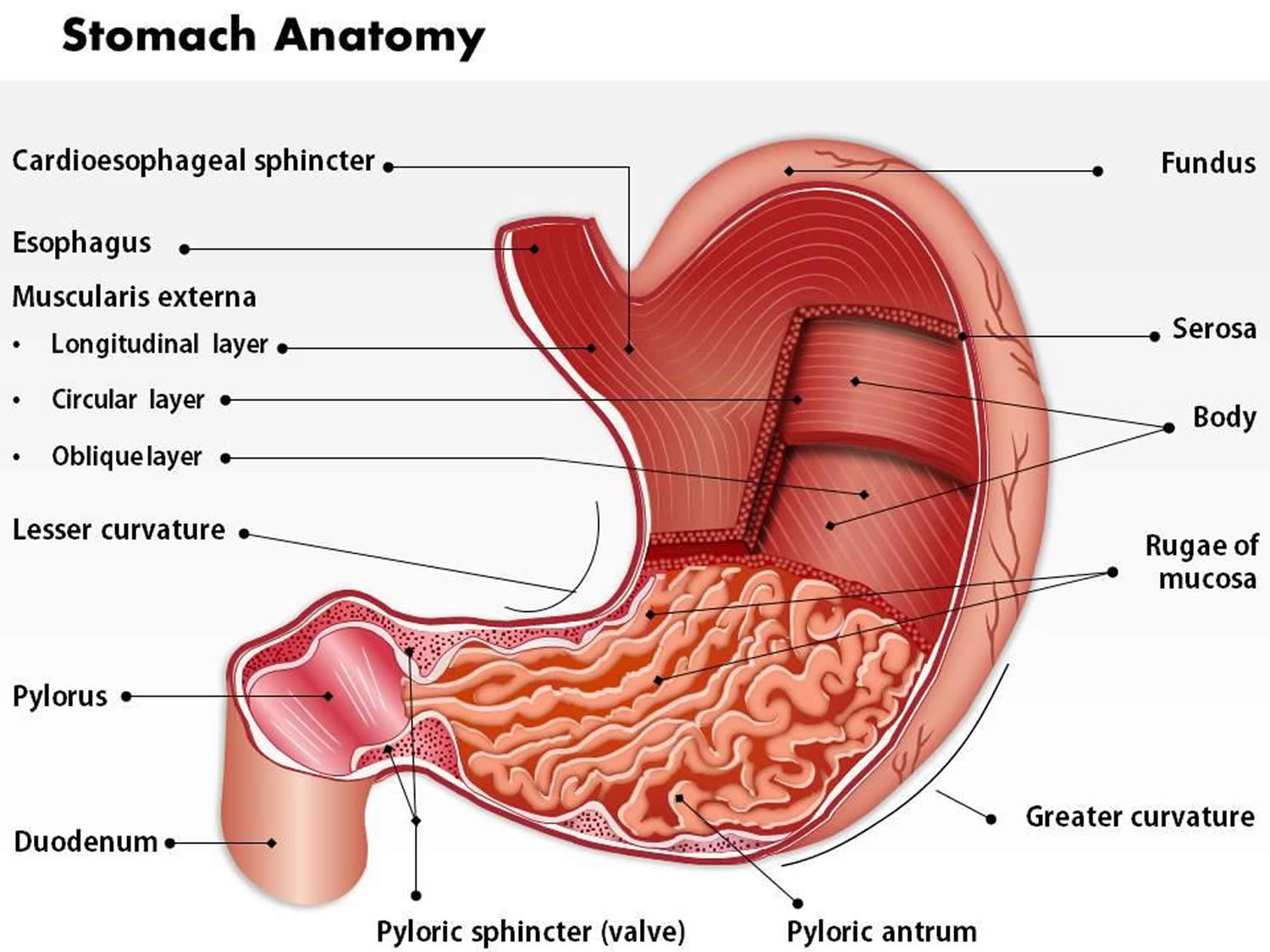

Figure 1. Stomach anatomy

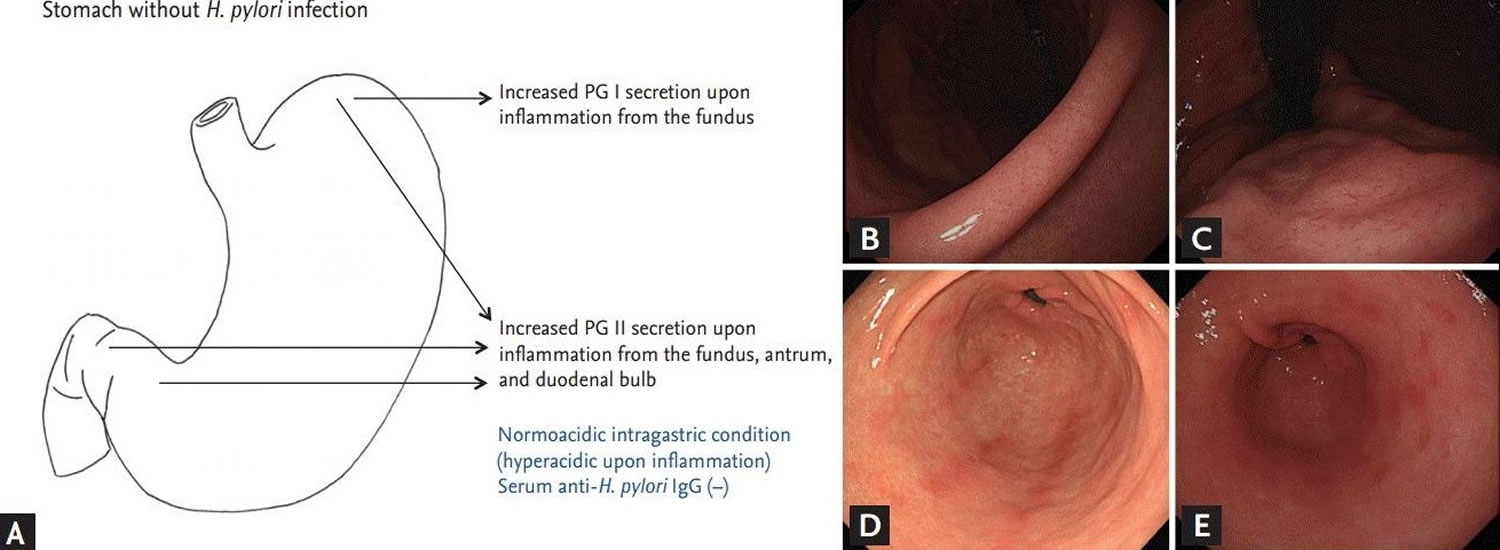

Figure 2. Chronic superficial gastritis (chronic superficial gastritis is characterized by multiple linear streaks on the greater curvature side of the antrum)

Footnotes: (A) Endoscopic findings in subjects without Helicobacter pylori infection. Pepsinogen (PG) I is produced exclusively by chief cells and mucus neck cells on the fundus. Pepsinogen (PG) II is secreted throughout the stomach and also from the Brunner’s gland of the duodenal bulb. (B) Normal endoscopic finding of the angle in noninfected subject. The regular arrangement of the collecting venules on the angle indicate normal gastric mucosa. (C) Normal finding of the corpus in the same subject. The regular arrangement of the collecting venules extends up to the on the cardia and fundus. (D) Chronic superficial gastritis. Several hyperemic streaks are noticed on greater curvature side of the antrum. (E) Erosive gastritis. Multiple raised, hyperemic erosions are visible on the antrum.

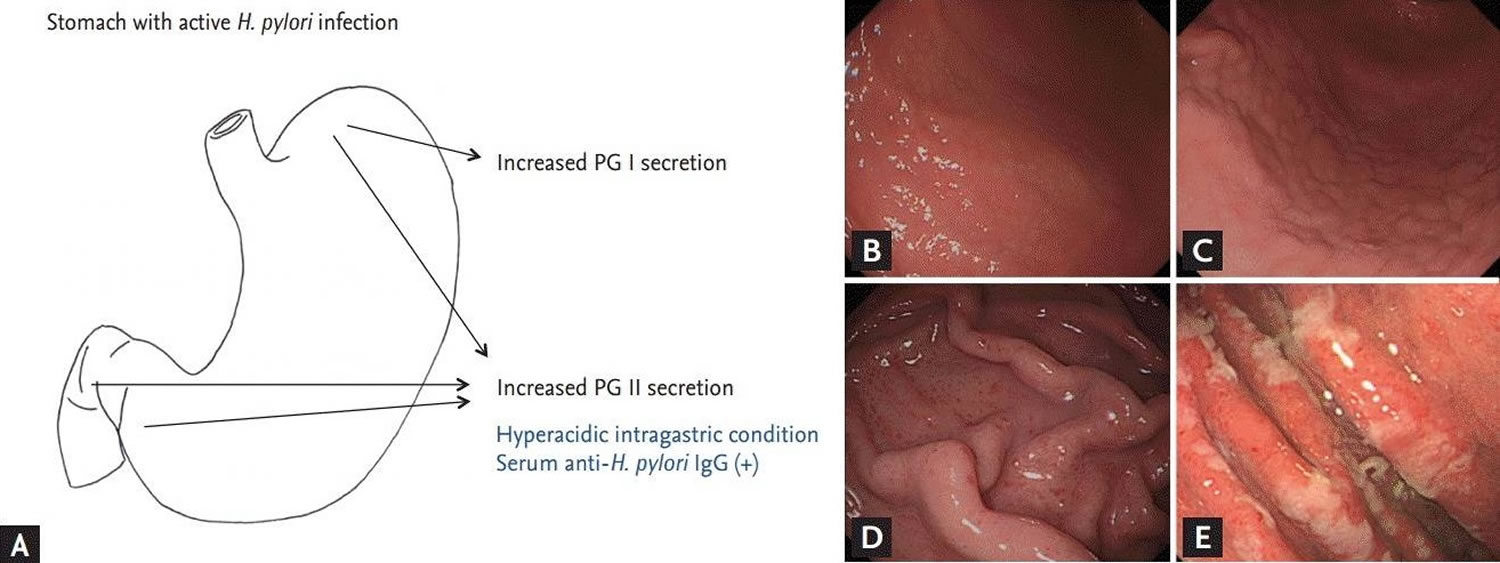

[Source 2 ]Figure 3. Helicobacter pylori gastritis

Footnotes: (A) Endoscopic findings in subjects with active Helicobacter pylori infection. (B) Nodular gastritis on the anterior-greater side of the proximal antrum. Multiple small nodules are visible on the antrum, extending up to greater curvature side of the corpus. The nodules consist of submucosal elevated lesions, and thus, there is no color change in nodular gastritis. (C) Follow-up findings of enlarged nodules on the proximal antrum to low-body in the same patient. The previously noted tiny, regular nodules have increased in size. The nodules were irregular and had grown from 12 months prior. (D) Finding of hemorrhagic spots on the fundus in nodular gastritis patient at initial endoscopy (B). Multiple tiny reddish spots, so-called diffuse redness, can be seen on the fundus and greater curvature side of the corpus. (E) Hypertrophic gastric folds. Thickened gastric rugae with whitish, sticky exudates indicate active H. pylori infection. PG = pepsinogen.

[Source 2 ]Nearly everyone has had a bout of indigestion and stomach irritation. Most cases of indigestion are short-lived and don’t require medical care. However, see your doctor if you have signs and symptoms of gastritis for a week or longer.

Seek medical care right away if your symptoms are severe, such as:

- Shortness of breath

- Trouble swallowing

- Ongoing vomiting

- Throwing up blood

- Sudden pain in chest, arm, neck, or jaw

- Cold sweats

- Your pain gets worse

- You have a fever

- Thick, black, or bloody stools (poop) as these may be signs of stomach bleeding.

Seek medical attention immediately if you have severe pain, if you have vomiting where you cannot hold any food down, or if you feel light-headed or dizzy. Tell your doctor if your stomach discomfort occurs after taking prescription or over-the-counter drugs, especially aspirin or other pain relievers.

Types of gastritis

The current classification of gastritis is based on time course (acute versus chronic), histological features, anatomic distribution, and underlying pathological mechanisms 3.

Classification of gastritis (Note this classification is continuously updated and hence is subject to change) 1:

- Helicobacter pylori-induced gastritis

- Drug-induced gastritis

- Autoimmune gastritis

- Stress-induced gastritis

- Special forms of gastritis

- Allergic gastritis

- Gastritis due to biliary reflux

- Gastritis due to duodenal reflux

- Lymphocytic gastritis

- Ménétrier disease

- Eosinophilic gastritis

- Infectious gastritis

- Gastric phlegmone

- Bacterial gastritis

- H. pylori-induced gastritis

- Helicobacter heilmannii gastritis

- Enterococcal gastritis

- Mycobacterial gastritis

- Tuberculous gastritis

- Non-tuberculous mycobacterial gastritis

- Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare gastritis

- Gastritis due to other specified non-tuberculous mycobacteria

- Secondary syphilitic gastritis

- Viral gastritis

- Cytomegaloviral gastritis

- Enteroviral gastritis

- Fungal gastritis

- Gastritis due to mucoromycosis

- Gastric candidiasis

- Gastric histoplasmosis

- Parasitic gastritis

- Gastric anisakiasis

- Cryptosporidium gastritis

- Gastric strongyloides stercoralis

- Viral gastritis

- Gastritis due to other diseases classified elsewhere

- Gastritis due to Crohn’s disease

- Gastritis due to sarcoidosis

- Gastritis due to vasculitis

- Gastritis due to external causes

- Alcoholic gastritis

- Radiation gastritis

- Chemical gastritis

- Gastritis due to other specified external causes

- Gastritis of unknown etiology with specific endoscopic or pathological features

- Superficial gastritis

- Acute superficial gastritis

- Chronic superficial gastritis

- Acute hemorrhagic gastritis

- Chronic atrophic gastritis

- Mild to moderate gastric atrophy

- Severe gastric atrophy

- Metaplastic gastritis

- Granulomatous gastritis

- Hypertrophic gastritis

- Superficial gastritis

- Other gastritis

- Chronic gastritis, not elsewhere classified

- Acute gastritis, not elsewhere classified

Acute gastritis

Acute gastritis is a condition in which the stomach lining known as the mucosa is inflamed or swollen. Acute gastritis starts suddenly and lasts for a short time. Acute gastritis will evolve to chronic gastritis, if not treated. For most people, however, acute gastritis isn’t serious and improves quickly with treatment.

Acute gastritis can be erosive or nonerosive:

- Erosive gastritis can cause the stomach lining to wear away, causing erosions—shallow breaks in the stomach lining—or ulcers—deep sores in the stomach lining.

- Nonerosive gastritis causes inflammation in the stomach lining; however, erosions or ulcers do not accompany nonerosive gastritis.

Clinical presentation, laboratory investigations, gastroscopy, as well as the histological and microbiological examination of tissue biopsies are essential for the diagnosis of gastritis and its causes. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis results in the rapid disappearance of polymorphonuclear infiltration and a reduction of chronic inflammatory infiltrate with the gradual normalization of the mucosa. Mucosal atrophy and metaplastic changes may resolve shortly, but it is not necessarily the outcome of treatment of Helicobacter pylori in all treated patients. Other types of gastritis should be treated based on their causative cause.

Health care providers treat acute gastritis with medications to:

- reduce the amount of acid in the stomach

- treat the underlying cause

In most cases you will be given antacids and other medicines to reduce your stomach acid. This will help ease your symptoms and heal your stomach lining.

If your gastritis is caused by an illness or infection, you should also treat that health problem.

If your gastritis is caused by the Helicobacter pylori bacteria, you will be given medicines to help kill the bacteria. In most cases you will take more than 1 antibiotics and a proton pump inhibitor (medicine that reduces the amount of acid in your stomach). You may also be given an antidiarrheal.

Do not have any foods, drinks, or medicines that cause symptoms or irritate your stomach. If you smoke, it is best to quit.

Acute gastritis key points

- Gastritis is a redness and swelling (inflammation) of the stomach lining.

- It can be caused by drinking too much alcohol, eating spicy foods, or smoking.

- Some diseases and other health issues can also cause gastritis.

- Symptoms may include stomach pain, belching, nausea, vomiting, abdominal bleeding, feeling full, and blood in vomit or stool.

- In most cases you will be given antacids and other medicines to reduce your stomach acid.

- Avoid foods or drinks that irritate your stomach lining.

- Stop smoking.

Acute gastritis treatment

Acute gastritis caused by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or alcohol may be relieved by stopping use of those substances.

Reducing the amount of acid in your stomach

The stomach lining of a person with gastritis may have less protection from acidic digestive juice. Reducing acid can promote healing of the stomach lining. Medications that reduce acid include:

- Antacids, such as Alka-Seltzer, Maalox, Mylanta, Rolaids, and Riopan. Many brands use different combinations of three basic salts—magnesium, aluminum, and calcium—along with hydroxide or bicarbonate ions to neutralize stomach acid. Antacids, however, can have side effects. Magnesium salt can lead to diarrhea, and aluminum salt can cause constipation. Magnesium and aluminum salts are often combined in a single product to balance these effects. Calcium carbonate antacids, such as Tums, Titralac, and Alka-2, can cause constipation.

- H2 blockers, such as cimetidine (Tagamet HB), famotidine (Pepcid AC), nizatidine (Axid AR), and ranitidine (Zantac 75). H2 blockers decrease acid production. They are available in both over-the-counter and prescription strengths.

- Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) include omeprazole (Prilosec, Zegerid), lansoprazole (Prevacid), dexlansoprazole (Dexilant), pantoprazole (Protonix), rabeprazole (AcipHex), and esomeprazole (Nexium). PPIs decrease acid production more effectively than H2 blockers. All of these medications are available by prescription. Omeprazole and lansoprazole are also available in over-the-counter strength.

Depending on the cause of gastritis, a health care provider may recommend additional treatments.

- Treating Helicobacter pylori infection with antibiotics is important, even if a person does not have symptoms from the infection. Curing the Helicobacter pylori infection often cures the gastritis and decreases the chance of developing complications, such as peptic ulcer disease, MALT lymphoma, and gastric cancer. A triple-therapy of clarithromycin/proton-pump inhibitor/amoxicillin for 14 to 21 days is considered the first line of treatment. Clarithromycin is preferred over metronidazole because the recurrence rates with clarithromycin are far less compared to a triple-therapy using metronidazole. However, in areas where clarithromycin resistance is known, metronidazole is the option of choice. Quadruple bismuth containing therapy would be of benefit, particularly if using metronidazole 4. After two eradication failures, H. pylori culture and tests for antibiotic resistance should be a consideration.

- Avoiding the cause of reactive gastritis can provide some people with a cure. For example, if prolonged NSAID use is the cause of the gastritis, a health care provider may advise the patient to stop taking the NSAIDs, reduce the dose, or change pain medications.

- Health care providers may prescribe medications to prevent or treat stress gastritis in a patient who is critically ill or injured. Medications to protect the stomach lining include sucralfate (Carafate), H2 blockers, and PPIs. Treating the underlying illness or injury most often cures stress gastritis.

- Health care providers may treat people with pernicious anemia due to autoimmune atrophic gastritis with vitamin B12 injections (parenteral 1000 micrograms or oral 1000 to 2000 micrograms). Monitor iron and folate levels, and eradicate any co-infection with Helicobacter pylori. Endoscopic surveillance for cancer risk and gastric neuroendocrine tumors is required 5.

Chronic gastritis

Chronic gastritis is a long lasting gastritis in which the stomach lining known as the mucosa is inflamed, or swollen. If chronic gastritis is not treated, it may last for years or even a lifetime. The stomach lining contains glands that produce stomach acid and an enzyme called pepsin. The stomach acid breaks down food and pepsin digests protein. A thick layer of mucus coats the stomach lining and helps prevent the acidic digestive juice from dissolving the stomach tissue. When the stomach lining is inflamed, it produces less acid and fewer enzymes. However, the stomach lining also produces less mucus and other substances that normally protect the stomach lining from acidic digestive juice.

Chronic gastritis can be erosive or nonerosive:

- Erosive gastritis can cause the stomach lining to wear away, causing erosions—shallow breaks in the stomach lining—or ulcers—deep sores in the stomach lining.

- Nonerosive gastritis causes inflammation in the stomach lining; however, erosions or ulcers do not accompany nonerosive gastritis.

Chronic gastritis may be caused by either infectious or noninfectious conditions. Infectious forms of gastritis include the following:

- Chronic gastritis caused by Helicobacter pylori infection. This is the most common cause of chronic gastritis 6

- Gastritis caused by Helicobacter heilmannii infection 7

- Granulomatous gastritis associated with gastric infections in mycobacteriosis, syphilis, histoplasmosis, mucormycosis, South American blastomycosis, anisakiasis, or anisakidosis

- Chronic gastritis associated with parasitic infections -Strongyloides species, schistosomiasis, or Diphyllobothrium latum

- Gastritis caused by viral (eg, CMV or herpesvirus) infection 8

Noninfectious forms of chronic gastritis include the following:

- Autoimmune gastritis. This is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by chronic atrophic gastritis and associated with raised serum anti-parietal and anti-intrinsic factor antibodies. The loss of parietal cells results in a reduction of gastric acid secretion, which is necessary for the absorption of inorganic iron. Therefore, iron deficiency is commonly a finding in patients with autoimmune gastritis. Iron deficiency in these patients usually precedes vitamin B12 deficiency. The disease is common in young women.

- Chemical gastropathy usually related to chronic bile reflux, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) and aspirin intake 9

- Uremic gastropathy

- Chronic noninfectious granulomatous gastritis 10 – This may be associated with Crohn disease, sarcoidosis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener granulomatosis), foreign bodies, cocaine use, isolated granulomatous gastritis, chronic granulomatous disease of childhood, eosinophilic granuloma, allergic granulomatosis and vasculitis, plasma cell granulomas, rheumatoid nodules, tumoral amyloidosis and granulomas associated with gastric carcinoma, gastric lymphoma, or Langerhans cell histiocytosis

- Lymphocytic gastritis, including gastritis associated with celiac disease (also called collagenous gastritis) 11. About 16% of patients with celiac disease have lymphocytic gastritis, which improves after a gluten-free diet, but there does not appear to be an association between lymphocytic gastritis and Helicobacter pylori 11. Chronic gastritis, whether active or inactive, does not appear to be affected by a gluten-free diet 11

- Eosinophilic gastritis. This is another rare cause of gastritis. The disease could be part of the eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders which is characterized by the absence of known causes of eosinophilia (not secondary to an infection, systematic inflammatory disease, or any other causes to explain the eosinophilia).

- Radiation injury to the stomach

- Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD)

- Ischemic gastritis. This is rare and associated with high mortality 12

- Gastritis secondary to drug therapy (NSAIDs and aspirin)

- Ménétrier disease. This disease is characterized by- (1) Presence of large gastric mucosal folds in the body and fundus of the stomach, (2) Massive foveolar hyperplasia of surface and glandular mucous cells, (3) Protein-losing gastropathy, hypoalbuminemia, and edema in 20 to 100% of patients, and (4) reduced gastric acid secretion because of loss of parietal cells 13.

Some patients have chronic gastritis of undetermined cause or gastritis of undetermined type (eg, autistic gastritis) 14.

The complications of chronic gastritis may include:

- Peptic ulcers. Peptic ulcers are sores involving the lining of the stomach or duodenum, the first part of the small intestine. NSAID use and H. pylori gastritis increase the chance of developing peptic ulcers.

- Atrophic gastritis. Atrophic gastritis happens when chronic inflammation of the stomach lining causes the loss of the stomach lining and glands. Chronic gastritis can progress to atrophic gastritis.

- Anemia. Erosive gastritis can cause chronic bleeding in the stomach, and the blood loss can lead to anemia. Anemia is a condition in which red blood cells are fewer or smaller than normal, which prevents the body’s cells from getting enough oxygen. Red blood cells contain hemoglobin, an iron-rich protein that gives blood its red color and enables the red blood cells to transport oxygen from the lungs to the tissues of the body. Research suggests that H. pylori gastritis and autoimmune atrophic gastritis can interfere with the body’s ability to absorb iron from food, which may also cause anemia.

- Vitamin B12 deficiency and pernicious anemia. People with autoimmune atrophic gastritis do not produce enough intrinsic factor. Intrinsic factor is a protein made in the stomach and helps the intestines absorb vitamin B12. The body needs vitamin B12 to make red blood cells and nerve cells. Poor absorption of vitamin B12 may lead to a type of anemia called pernicious anemia.

- Growths in the stomach lining. Chronic gastritis increases the chance of developing benign, or noncancerous, and malignant, or cancerous, growths in the stomach lining. Chronic H. pylori gastritis increases the chance of developing a type of cancer called gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma.

Chronic gastritis treatment

Treatment of chronic gastritis can be aimed at treating the underlying cause. When chronic gastritis represents gastric involvement of a systemic disease, treatment is directed toward the primary disease.

Depending on the cause of chronic gastritis, a health care provider may recommend additional treatments.

- Treating Helicobacter pylori infection with antibiotics is important, even if a person does not have symptoms from the infection. Curing the infection often cures the gastritis and decreases the chance of developing complications, such as peptic ulcer disease, MALT lymphoma, and gastric cancer. A triple-therapy of clarithromycin/proton-pump inhibitor/amoxicillin for 14 to 21 days is considered the first line of treatment. Clarithromycin is preferred over metronidazole because the recurrence rates with clarithromycin are far less compared to a triple-therapy using metronidazole 15. However, in areas where clarithromycin resistance is known, metronidazole is the option of choice. Quadruple bismuth containing therapy would be of benefit, particularly if using metronidazole 4. If a patient was treated for Helicobacter pylori infection, confirm that the organism has been eradicated. Evaluate eradication at least 4 weeks after the beginning of treatment. Eradication may be assessed by means of noninvasive methods such as the urea breath test or the stool antigen test.

- Avoiding the cause of reactive gastritis can provide some people with a cure. For example, if prolonged NSAID use is the cause of the gastritis, a health care provider may advise the patient to stop taking the NSAIDs, reduce the dose, or change pain medications.

- Health care providers may prescribe medications to prevent or treat stress gastritis in a patient who is critically ill or injured. Medications to protect the stomach lining include sucralfate (Carafate), H2 blockers, and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). Treating the underlying illness or injury most often cures stress gastritis.

- Health care providers may treat people with pernicious anemia due to autoimmune atrophic gastritis with vitamin B12 injections

Some entities manifested by chronic gastritis do not have well-established treatment protocols. For example, in lymphocytic gastritis, some cases of spontaneous healing have been reported. However, because the disease has a chronic course, treatment is recommended. Some studies have reported successful treatment of exudative lymphocytic gastritis with omeprazole.

Alcohol gastritis

Drinking alcohol excessively can erode the lining of the stomach, making it weaker and more likely to be damaged by the stomach’s acidic digestive juices.

Atrophic gastritis

Atrophic gastritis is characterized by chronic inflammation of the stomach lining (gastric mucosa) with loss of the gastric glandular cells and replacement by intestinal-type epithelium, pyloric-type glands, and fibrous tissue 16. Atrophy of the gastric mucosa is the endpoint of chronic processes, such as chronic gastritis associated with Helicobacter pylori infection, other unidentified environmental factors, and autoimmunity directed against gastric glandular cells (autoimmune gastritis) 16.

Atrophic gastritis represents the end stage of chronic gastritis, both infectious and autoimmune. In both cases, the clinical manifestations of atrophic gastritis are those of chronic gastritis, but pernicious anemia is observed specifically in patients with autoimmune gastritis and not in those with Helicobacter pylori–associated atrophic gastritis.

The 2 main causes of atrophic gastritis result in distinct topographic types of gastritis, which can be distinguished histologically. Helicobacter pylori–associated atrophic gastritis is usually a multifocal process that involves both the antrum and the oxyntic mucosa of the gastric corpus and fundus, whereas autoimmune gastritis essentially is restricted to the gastric corpus and fundus. Individuals with autoimmune gastritis may develop pernicious anemia because of extensive loss of parietal cell mass and anti-intrinsic factor antibodies 17.

Helicobacter pylori–associated atrophic gastritis is frequently asymptomatic, but individuals with this disease are at increased risk of developing gastric carcinoma, which may decrease following Helicobacter pylori eradication 18. Patients with chronic atrophic gastritis develop low gastric acid output and hypergastrinemia, which may lead to enterochromaffin-like cell hyperplasia and carcinoid tumors 19.

Atrophic gastritis treatment

Once atrophic gastritis is diagnosed, treatment can be directed (1) to eliminate the causal agent, which is a possibility in cases of Helicobacter pylori–associated atrophic gastritis; (2) to correct complications of the disease, especially in patients with autoimmune atrophic gastritis who develop pernicious anemia (in whom vitamin B-12 replacement therapy is indicated); or (3) to attempt to reverse the atrophic process.

No consensus from different studies exists regarding the reversibility of atrophic gastritis; however, removal of Helicobacter pylori from the already atrophic stomach may block further progression of the disease. Until recently, specific recommendations for Helicobacter pylori eradication were limited to peptic ulcer disease. At the Digestive Health Initiative International Update Conference on Helicobacter pylori held in the United States, the recommendations for Helicobacter pylori testing and treatment were broadened. Helicobacter pylori testing and eradication of the infection also were recommended after resection of early gastric cancer and for low-grade mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma.

If Helicobacter pylori is identified as the underlying cause of gastritis, subsequent eradication now is almost generally an accepted practice. Protocols for Helicobacter pylori eradication require a combination of antimicrobial agents and antisecretory agents, such as a proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), ranitidine bismuth citrate (RBC), or bismuth subsalicylate. Despite the combinatorial effect of drugs in regimens used to treat Helicobacter pylori infection, cure rates remain, at best, 80-95%.

Lack of patient compliance and antimicrobial resistance are the most important factors influencing poor outcome. Currently, the most widely used and efficient therapies to eradicate Helicobacter pylori are triple therapies (recommended as first-line treatments) and quadruple therapies (recommended as second-line treatment when triple therapies fail to eradicate Helicobacter pylori). In both cases, the best results are achieved by administering therapy for 10-14 days, although some studies have recommended the duration of treatment of 7 days. The accepted definition of cure is no evidence of Helicobacter pylori 4 or more weeks after ending the antimicrobial therapy.

Helicobacter pylori gastritis

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) a spiral shaped, microaerophilic, Gram-negative bacterium with a flagella that enables it to colonize the human gastrointestinal tract for millennia 20, causing inflammatory changes, that vary from asymptomatic mild gastritis to peptic ulcer, as well as precancerous lesions such as chronic atrophic gastritis or gastric intestinal metaplasia and malignant tumors, including gastric lymphoma, epithelial gastric neoplasia and gastric cancer 21. Gastric intestinal metaplasia is defined as the replacement of the gastric epithelium by two types of intestinal-type epithelium, which can be seen by Haematoxylin-eosin staining: (1) absorptive enterocytes with brush border along with goblet cells; and (2) columnar cells with foamy cytoplasm but lacking brush border 22. Furthermore, it is divided into three phenotypes by alcian blue and high-iron diamine staining as described by Filipe and Jass 23, namely type 1 (complete or small intestinal type) and types 2 and 3 (incomplete or colonic type). When more than one type of gastric intestinal metaplasia coexisted in a given sample, the case was classified according to the dominant type present in the section 23. Gastric intestinal metaplasia is generally considered to be a condition that predisposes to malignancy, and also the presence of incomplete-type gastric intestinal metaplasia (type 3) and a higher proportion of this type indicate a higher cancer risk, especially intestinal-type gastric cancer 24.

A small proportion of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infected patients develop peptic ulceration (approximately 15%) or gastric adenocarcinoma (0.5%-2%) and gastric mucosa–associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma 25. Several factors affect the patterns of disease outcome associated with H pylori infection, including: (1) the virulence of the strain; (2) host genetic susceptibility factors and host immune response to infection; and (3) modulating environmental factors such as diet or smoking 26.

Worldwide, the epidemiology of H. pylori infection, which affects approximately 50% of the world’s population, overlaps that of gastritis 27. Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) bacterial infection is highly prevalent in Asia as well as Central and South America, and it is generally most prevalent in developing countries. The known long-term complications of chronic gastritis, namely atrophic gastritis and gastric adenocarcinoma, are significantly more prevalent in these areas of the world 28, 29. Helicobacter pylori treatment seems to improve chronic atrophic gastritis and gastric intestinal metaplasia, many studies, including meta-analysis, show that H. pylori eradication reduces gastric cancer 21.

In the United States, approximately 17.1% of the population are infected with H. pylori 30, but the prevalence of infection in minority groups, immigrants from developing countries, and those with low socioeconomic status is much higher 28. The infection is usually acquired during childhood; children aged 2-8 years in developing nations acquire the infection at a rate of about 10% per year. In contrast, US children become infected at a rate of less than 1% per year. This difference in the rate of H pylori infection in childhood underscores the differences in epidemiology of Helicobacter -associated diseases between developed and developing countries 31.

Socioeconomic differences are the most important predictor of the prevalence of the infection in any group 28. Higher standards of living are associated with higher levels of education and better sanitation, which results in lower prevalence of H pylori gastritis. In the United States and in other countries with modern sanitation and clean water supplies, the rate of acquisition has been decreasing since 1950. The rate of infection in people with several generations of their families living at a high socioeconomic status is in the range of 10%-15% 31. This is probably the lowest the prevalence can decline spontaneously until eradication or vaccination programs are instituted.

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) has evolved various mechanisms to promote its survival in the stomach’s acidic environment and increase its ability to cause infection. One such adaptation is urease, an enzyme that hydrolyzes urea and releases ammonia, which in turn neutralizes gastric acid, allowing H. pylori to survive and colonize the gastric mucosa 32. The other main feature of H. pylori is its ability to adhere to the gastric epithelium, which is achieved through receptor-mediated adhesion via an array of outer membrane proteins 33. These proteins include adherence lipoprotein A and B (AlpA/B), blood group antigen binding adhesion (BabA), outer inflammatory protein A (OipA) and sialic acid binding adhesion (SabA). Although many other proteins in this class may play a role in cell adhesion and infection, the aforementioned are the major players 21. Additionally, cellular damage is achieved predominantly through the effects of two genes: vacuolating cytotoxin A (VacA) and cytotoxin associated gene A (CagA) which mechanism of action and interaction will be discussed in depth later in this article. Even though H. pylori is considered a non-invasive bacterium, there is some data supports its ability for intracellular invasion through mechanisms not yet fully understood 34.

Acute Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is usually not clinically detected 1. Experimental infection results in a clinical syndrome characterized by epigastric pain, fullness, nausea, vomiting, flatulence, malaise, and sometimes fever. Persistence of H pylori causes chronic gastritis, which is generally asymptomatic but may present with epigastric pain or, rarely, with nausea, vomiting, anorexia, or significant weight loss. Symptoms may occur with the development of complications of chronic H pylori gastritis, which include peptic ulcers, gastric adenocarcinoma, and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma 35. Prospective data in a Japanese population showed that Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication in patients with endoscopically resected early gastric cancer was associated with decreased appearance of new early cancers 36. The stomach represents the primary organ affected by H. pylori infection and is also the most common site for primary gastrointestinal lymphomas, accounting for more than 75% of cases 37. Notably, H. pylori eradication alone may be sufficient to cure early stage MALT lymphoma.

The findings associated with Helicobacter pylori gastritis and its complications are most commonly evaluated by endoscopic examination with esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) procedures.

Cakmakci et al 38 conducted a study to determine whether transabdominal ultrasonography may have a role in the detection of antral gastritis and H. pylori infection in the antrum. The investigators concluded that antral gastritis caused by Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is associated with thickening of antral walls and mucosal layers, as evidenced on ultrasonography. They suggest that these findings may be useful in the diagnosis of gastritis and in avoiding unnecessary interventions and measures 38.

Treatment for Helicobacter pylori gastritis

All patients diagnosed with Helicobacter pylori infection should be treated 39. Left untreated, Helicobacter pylori gastritis has a 15%-20% lifetime risk of developing peptic ulcer disease 40. Patients with H pylori –associated chronic gastritis may be asymptomatic or present with dyspeptic symptoms or with specific complications such as gastric ulcers, carcinoma, or mucosa–associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma. More than 90% of primary gastric MALT lymphomas are seen in patients with Helicobacter pylori gastritis 40.

The prevalence of H. pylori resistance to commonly used antimicrobial agents greatly varies geographically and is linked to consumption of antibiotics in the region 41, so the preferred eradication regimen often differs between regions. Ideally, treatment regimens should be chosen based on susceptibility testing. Within any region, only regimens that reliably produce eradication rates of ≥90% in that population should be used for empirical treatment 42.

A triple-therapy of clarithromycin/proton-pump inhibitor/amoxicillin for 14 to 21 days is considered the first line of treatment 3. Clarithromycin is preferred over metronidazole because the recurrence rates with clarithromycin are far less compared to a triple-therapy using metronidazole. However, in areas where clarithromycin resistance is known, metronidazole is the option of choice. Quadruple bismuth containing therapy would be of benefit, particularly if using metronidazole 43.

After two eradication failures, H. pylori culture and tests for antibiotic resistance should be a consideration.

Autoimmune gastritis

Autoimmune gastritis occurs when your body attacks the cells that make up your stomach lining; characterized by chronic atrophic gastritis limited to the corpus and fundus of the stomach that is causing marked diffuse atrophy of parietal and chief cells. This reaction can wear away at your stomach’s protective barrier. Autoimmune gastritis is more common in people with other autoimmune disorders, including Hashimoto’s disease, type 1 diabetes, Addison disease, chronic spontaneous urticaria, myasthenia gravis, vitiligo and perioral cutaneous autoimmune disorders especially erosive oral lichen planus 44. The association between chronic atrophic autoimmune gastritis and autoimmune thyroid disease earned the name in the early 60s of “thyrogastric syndrome” 3. Autoimmune gastritis can also be associated with vitamin B-12 deficiency.

The pathogenesis of autoimmune gastritis focuses on two theories. According to the first theory, an immune response against superimposed H. pylori antigen gets triggered, antigen cross-reacting with antigens within the proton-pump protein or the intrinsic factor, leading to a cascade of cellular changes and causing damages to the parietal cells and stopping hydrochloric acid secretion and thus these cells gradually become atrophic and not functioning. The second theory assumes that the autoimmune disorder develops irrespective of H. pylori infection, and it directs itself against the proteins of the proton-pump. As per both theories, the autoimmune gastritis is the result of a complex interaction between genetic susceptibility and environmental factors resulting in immunological dysregulation involving sensitized T lymphocytes and autoantibodies directed against parietal cells and the intrinsic factor 45.

The diagnosis of autoimmune gastritis centers on laboratory and histological examination. These include: (1) atrophic gastritis of gastric corpus (body) and fundus of the stomach, (2) autoantibodies against the intrinsic factor and the parietal cells, (3) raised serum gastrin levels, (4) serum pepsinogen 1 level and (5) pepsinogen 1 to pepsinogen 2 ratios 46, 47.

Autoimmune gastritis associated with serum anti-parietal and anti-intrinsic factor antibodies; with the most sensitive serum biomarker in autoimmune gastritis is parietal cell antibodies (as compared to intrinsic factor antibodies). Other tests that may be necessary for autoimmune gastritis are gastrin-17, IgG, and anti-H. pylori antibodies, cytokines (such as IL-8), and ghrelin (a growth-hormone-releasing peptide that is produced mainly by the gastric fundus mucosa) 48.

The determination of the risk of gastric cancer in autoimmune gastritis is by (1) low levels of pepsinogen 1, (2) low pepsinogen 1/pepsinogen 2 ratios, (3) high fasting serum gastrin, (4) atrophic gastritis of the corpus and fundus. In these patients, the risk of cancer is high irrespective of whether they have or do not have on-going H. pylori infection.

Autoimmune gastritis treatment

Substitution of deficient iron and vitamin B12 (parenteral 1000 micrograms or oral 1000 to 2000 micrograms) is needed. Monitor iron and folate levels, and eradicate any co-infection with H. pylori. Endoscopic surveillance for cancer risk and gastric neuroendocrine tumors (NET) is required 49, 50.

Eosinophilic gastritis

Eosinophilic gastritis is one of the eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders (EGIDs) characterized by pathologic accumulation of eosinophils into the gastrointestinal tract 51. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis may affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract from the esophagus to the rectum. The eosinophilic infiltration may involve one or more layers of the gastrointestinal wall. Most commonly, the stomach wall (eosinophilic gastritis) and the small bowel (eosinophilic enteritis) are involved. The particular symptoms present in each person depend upon the layer and the location of involvement. In clinical practice, the Klein classification system 52 is used to categorize the disease type according to the involved intestinal layer; the 3 Klein categories are mucosal, muscular and serosal. The mucosal layer is the most commonly affected, as has been reported in the majority of case series in the literature, with prevalence ranging between 57% in older estimates 53 and 88% to 100% in more recent estimates 54. Furthermore, the muscular and serosal types are commonly associated with concomitant mucosal eosinophilic infiltration, which raises the hypothesis of centrifugal disease progression from the deep mucosa toward the muscular and serosal layers 55.

Eosinophilic gastritis can present with varying symptoms which are often debilitating and may include abdominal pain, dysphagia (sometimes presenting as food impaction), heartburn, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, weight loss, and bloating (ascites is possible) 56, 57. Mucosal involvement leads to protein-losing enteropathy and malabsorption. Muscle layer involvement causes abdominal pain, vomiting, dyspeptic symptoms and bowel obstruction. Subserosal involvement predominantly causes ascites with marked eosinophilia. Sometimes eosinophilic pleural effusion is present. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis is a chronic, waxing and waning condition.

The chronic nature of eosinophilic gastritis can significantly impair patients’ health-related quality of life 58. Results from a qualitative health-related quality of life assessment showed that patients reported that symptoms associated with eosinophilic gastritis negatively impacted their social functioning, ability to engage in activities involving food, and impaired perceptions of their body image and ability to sleep 58.

The standardized estimated prevalence rates of eosinophilic gastritis in the USA is 6.3 cases per 100,000 59, with a slightly increasing incidence over the past 50 years 55. However, a considerable portion of cases may be undetected as there is no dedicated consensus on how to diagnose the condition 60. Therefore, the true prevalence of eosinophilic gastritis is unknown and likely underestimated 61. Additionally, eosinophilic gastroenteritis is well known to be more common among the pediatric population, with afflicted adults typically between the 3rd and 5th decade of life 53. Intriguingly, the more recent estimates of eosinophilic gastroenteritis in the United States have found a shift from male preponderance 62 to female predominance 63. Higher socioeconomic status, Caucasian race and excess weight may be risk factors of eosinophilic gastroenteritis 55 and a possible hereditary component (genetic factor) is suggested by reports of familial cases 64.

The exact cause of eosinophilic gastroenteritis is unknown. Some cases of this disease may be caused by a hypersensitivity to certain foods or other unknown allergens 65. Often, a family history of atopic diseases is present 64% of reported cases 66. Atopy (asthma, hay fever or eczema) is present in a subset of patients. Food allergies are common. Concomitant allergic disorders, including asthma, rhinitis, eczema and drug or food intolerances, are present in 45% to 63% of the reported eosinophilic gastroenteritis cases[ 59. Some studies have found an association with other autoimmune conditions, such as celiac disease 67, ulcerative colitis 68 and systemic lupus erythematosus 69. These data collectively suggest that eosinophilic gastroenteritis may result from immune dysregulation in response to an allergic reaction; yet, a triggering allergen is not always identified. About 50% of eosinophilic gastroenteritis cases involving the alimentary tract have been detected by allergy testing to address a suspected food allergy 55. Other environmental factors, such as parasitic infestation and drugs, may act as predisposing agents as well 70.

Both immunoglobulin E (IgE) dependent and delayed TH2 cell-mediated allergic mechanisms have been demonstrated to be involved in the pathogenesis of eosinophilic gastroenteritis 57. Interleukin 5 (IL-5) has also been shown to play an essential role in the expansion of eosinophils and their recruitment to the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, the mechanism underlying the pathogenic hallmark of eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Chemokines, namely eotaxin 1 and α4β7 integrin, are also known to contribute to eosinophilic homing inside the intestinal wall. Other mediators-most notably IL-3, IL-4, IL-13, leukotrienes and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha-act to enhance eosinophilic trafficking and have been proposed to help in prolonging lymphocytic and eosinophilic activity 71, 72. Many of these immune-related molecules are currently under consideration as potential targets for molecular therapy of eosinophilic gastroenteritis.

Once recruited to the gastrointestinal tract, the activated eosinophils induce a significant inflammatory response by secreting a variety of mediators including the cytotoxic granules that lead to structural damage in the infiltrated intestinal layers 72. Thus, eosinophilic gastroenteritis can affect any gastrointestinal segment, but reports have shown that the small intestine and stomach are the most predominant areas 53.

Some patients present with elevated IgE and eosinophilia of tissue and blood. A careful history may suggest to the physician that a biopsy is required. The results of the biopsy (endoscopic or full-thickness surgical biopsy) are usually diagnostic. Diagnosis of eosinophilic gastroenteritis requires three criteria, namely: (1) presence of gastrointestinal symptoms; (2) histologic evidence of eosinophilic infiltration in one or more areas of the gastrointestinal tract; and (3) exclusion of other causes of tissue eosinophilia 73.

Eosinophilic gastritis treatment

Currently, no treatments have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for eosinophilic gastritis. The clinical management of eosinophilic gastritis focuses on supportive care to manage symptoms 65. Eliminating foods to which a person is allergic may prove helpful in some cases. The overall data in the literature is insufficient to recommend empiric and total elimination diets in routine management; however, an elemental diet can be used initially as adjunct treatment for severe cases 57. In general, when a limited number of food allergens is detected, patients should be maintained on a “targeted elimination diet” 57. When many or no allergens are identified, the more aggressive “empiric elimination diet” or “elemental diet” can be used 57. Lucendo et al 74 investigated dietary treatment efficacy in EGE through a systematic review and found significant improvement in most cases, especially in those who undertook the elemental diet, which induced clinical remission in > 75% of cases. However, the validity of such a high efficacy rate was questionable since no confirmation of histologic response was available for the majority of cases included in the review. On the other hand, the authors noted that dietary measures were predominantly considered in the setting of mucosal disease, which is well known to be associated with food allergy, while the efficacy in muscular and serosal types, which show weaker linkage to food allergy 53, was only rarely reported. In addition, patients’ adherence and tolerability to such strategies remain an important drawback, especially when empiric elimination or elemental diets are used.

The corticosteroid drug prednisoneis usually an effective treatment for eosinophilic gastroenteritis 55, 66. The recommended initial dose of 0.5 to 1 mg/kg usually induces remission within a 2 week period, with the most dramatic response occurring in patients with the serosal type 75. Thereafter, tapering dosage over a 6 to 8 week period is recommended. Re-evaluation of the eosinophilic gastroenteritis diagnosis (and type) must be considered in cases of initial unresponsiveness 76. Steroid dependent disease reportedly accounts for about 20% of cases 66 and, consequently, low doses of prednisone may be needed to maintain remission. Unfortunately, long-term steroid treatment predisposes some patients to serious side effects; in such cases, steroid-sparing agents can be of benefit.

Sometimes budesonide, a common steroid treatment of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, can be helpful and produces fewer side effects due to its lower systemic impact. It has also been demonstrated as effective for induction and maintenance of remission in the majority of reported cases 54. The usual dose is 9 mg/day, which can be tapered to 6 mg/day for use as prolonged maintenance therapy 57. The better safety profile of budesonide, compared to other steroid drugs, is of particular benefit for management of eosinophilic gastroenteritis cases over the long term, especially in the setting of steroid dependent disease.

Azathioprine, a common immunosuppressive agent used in organ transplant and patients with autoimmune diseases, may be worth trying 57. The efficacy of this steroid-sparing agent has been demonstrated in patients with steroid dependent and refractory eosinophilic gastroenteritis disease 57. The usual dose for eosinophilic gastroenteritis patients is similar to that used in patients with IBD (2-2.5 mg/kg) 77; lower doses may not be effective 78.

Montelukast sodium, commonly used to treat asthma, is a selective leukotriene (LTD4) inhibitor with demonstrated efficacy for various eosinophilic disorders, including eosinophilic gastroenteritis. The majority of reports in the literature concerning its use in eosinophilic gastroenteritis have shown significant clinical response in patients, either when the drug is used alone or in combination with steroids for induction and maintenance of remission in steroid dependent or refractory disease 79, 54. The usual dose is 5-10 mg/day.

Oral cromolyn sodium is a mast cell stabilizer that blocks the release of immune mediators and the subsequent activation of eosinophils. While it has been shown to have significant efficacy in many of the reported cases of eosinophilic gastroenteritis, its effect was only modest in others, for unknown reasons 80, 81, 82. The usual dose is 200 mg three times daily or four times daily.

Ketotifene is a 2nd-generation H1-antihistamine agent that also modulates the release of mast cell mediators. Melamed et al 83 described 6 patients with eosinophilic gastroenteritis who responded clinically and histologically to ketotifen; however, Freeman et al 84 reported a single case in which the drug failed to maintain disease remission. This agent has also been proposed as an adjunct to steroids and montelukast for treating refractory eosinophilic gastroenteritis 62. The usual dose is 1-2 mg twice daily.

Biologic agents have also been reported in some case studies of eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Mepolizumab (anti-IL5) was reported to have improved tissue and peripheral eosinophilia, but without relieving symptoms, in 4 patients with eosinophilic gastroenteritis 85; unfortunately, another report associated its use with rebound hypereosinophilia 86. Omalizumab (anti-IgE) was reported to similarly result in a significant histologic response 87 but to be unlikely to efficiently treat eosinophilic gastroenteritis patients with a serum IgE level > 700 kIU/L 88. Infliximab (anti-TNF) was reported as highly effective for inducing remission in refractory eosinophilic gastroenteritis, but its use is limited by the development of resistance and secondary loss of response, both of which can be managed by switching to adalimumab 89.

Other modalities include intravenous immunoglobulin and interferon-alpha, both of which appear to be effective in treating severe refractory and steroid dependent cases 90, 69. Suplatast tosilate, a TH2 cytokine inhibitor, can be beneficial as well 91. Finally, fecal microbiota transplantation has also been reported to improve diarrhea in a patient with eosinophilic gastroenteritis, even before its application in combination with steroids 92.

Surgery may be necessary in cases of severe disease that are complicated by perforation, intussusception or intestinal obstruction 93. It has been reported that about 40% of eosinophilic gastroenteritis patients may need surgery during the course of their disease, and about half of those may experience persistent symptoms postoperatively 94.

Other treatment is symptomatic and supportive.

Despite the range of therapeutic approaches, symptomatic relief is typically short-lived 60 and prolonged use of therapies such as corticosteroids increases the risk of serious adverse events 57. Additionally, dietary restrictions and food elimination may negatively impact quality of life 95. Furthermore, many patients require ongoing treatment and continue to experience chronic gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms despite treatment 96.

Phlegmonous gastritis

Phlegmonous gastritis is a rare but rapidly progressing and often fatal bacterial infection of the stomach wall (mainly occurring in the submucosa of the stomach) affecting both sexes (mostly men with male to female ratio of 2:1) between the ages of 30 and 70, especially over 50 years 97, 98. Mortality varies between 10 and 54% and is higher in the diffuse type of diseases, especially in gangrenous or necrotizing gastritis 99. Most of the phlegmonous gastritis cases are caused by streptococci, pneumococci, Escherichia coli, Proteus, Haemophilus, staphylococci, and Corynebacterium 100. With the high mortality of this disease, early recognition and immediate action are crucial.

At present, acute phlegmonous gastritis cause is not entirely clear presumably due to bacteria invading the stomach. Hemolytic streptococcus is reportedly found in approximately 70% of cases, followed by Staphylococcus aureus, Pneumococcus, and Enterococcus 101. Bacterial invasion of the gastric wall can be caused by gastric ulcer, chronic gastritis, and the like, with the pathogenic bacteria of the pharynx directly infringing into the damaged mucosa; respiratory tract infection or other infection, with the pathogenic bacteria entering the gastric wall through blood flow; the pathogenic bacteria entering the gastric wall through the lymphatic system in the case of cholecystitis and peritonitis 97. Several predisposing factors (either local or general) and underlying situations have been associated with the disease. Local factors include mucosal injury, achlorhydria, gastritis, alcohol use, gastrointestinal malignancies, invasive endoscopic procedures, and gastric lymphoma 102. Furthermore, alcohol consumption, malnutrition, diabetes mellitus, being elderly and impaired immune status, such as gastric lymphoma, HIV infection, hematologic malignancies, or connective tissue disorders may contribute to the manifestation of the disease 103, 104. An association with pregnancy has also been described 105. In almost 50% of the cases, no predisposing factors have been identified.

Phlegmonous gastritis diagnosis is often delayed due to nonspecific symptoms such as including acute abdominal disease, sudden onset of abdominal pain, high fever, chills, nausea, and vomiting. With less than 500 cases reported in the literature, it requires the attention of medical staff. With the development of the disease, body temperature can increase, peritoneal irritation signs become obvious, such as abdominal tenderness, rebound pain, and the vomitus can change to abscess fluid 106. Abdominal CT typically reveals the following characteristic findings of phlegmonous gastritis: thickening of the gastric wall, low-intensity areas within the gastric wall (indicative of an abscess), and gas accumulation 107.

Phlegmonous gastritis treatment

Acute phlegmonous gastritis has an extremely high mortality rate, and the key to successful treatment is early diagnosis and treatment. Phlegmonous gastritis is caused by suppurative bacterial infection and is conventionally managed by conservative treatment using antibiotics. In severe cases, immediate surgical treatment is generally required. Surgical treatment is necessary for cases presenting with local complications, such as perforation or cases that have evolved to gastric necrosis. Total gastrectomy is sometimes necessary. Before the advent of antibiotics, the fatality rate was as high as 83% to 92%, and the mortality rate reduced to 48% even after antibiotics became available 108. In addition, nutritional support and rehydration are very important to the success of the treatment 109.

Gastritis symptoms

Not everyone with gastritis will experience symptoms. The signs and symptoms of gastritis may include:

- a burning pain in the upper stomach area (such as in heartburn) — which may improve or worsen with eating

- acid reflux or gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

- nausea

- vomiting

- loss of appetite

- bloating and burping

- hiccups

- diarrhea

- feeling uncomfortably full after eating

- gurgling stomach and/or gas

- weight loss

- bad breath

- blood in the vomit or stools (poop)

Gastritis complications

If left untreated, gastritis can lead to stomach ulcers and stomach bleeding. Rarely, some forms of chronic gastritis may increase your risk of stomach cancer, especially if you have extensive thinning of the stomach lining and changes in the lining’s cells. Tell your doctor if your signs and symptoms aren’t improving despite treatment for gastritis.

Possible complications of gastritis:

- Peptic ulcer

- Chronic atrophic gastritis (loss of appropriate glands resulting mainly from long-standing H. pylori infection)

- Gastric metaplasia/dysplasia

- Gastric cancer (adenocarcinoma)

- Iron-deficiency anemia (chronic gastritis and early stages of gastric autoimmunity)

- Vitamin B12 deficiency (autoimmune gastritis)

- Gastric bleeding

- Achlorhydria (autoimmune gastritis, chronic gastritis)

- Gastric perforation

- Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma

- Neuroendocrine tumors (NET) (previously referred to as gastric carcinoid; complicates autoimmune gastritis)

- Autoimmune gastritis predisposes to the development of both gastric adenocarcinoma and gastric type 1 NET

- The development of neuroendocrine tumors (NET) in these patients is related to mucosal atrophy and hyperplasia of immature mucus neck cells

- The enhanced differentiation of immature precursor neck cells into histamine-producing enterochromaffin-like cells secondary to hypergastrinemia is the process

- Vitamin C, vitamin D, folic acid, zinc, magnesium, and calcium deficiency (atrophic autoimmune gastritis)

Cause of gastritis

Gastritis is an inflammation of the stomach lining. Weaknesses or injury to the mucus-lined barrier that protects your stomach wall allows digestive juices to damage and inflame the stomach lining. There are many things that can increase your risk of gastritis. Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is the most common cause of gastritis worldwide 21. However, 60 to 70% of Helicobacter pylori-negative subjects with functional dyspepsia (unknown cause for indigestion) or non-erosive gastroesophageal reflux were also found to have gastritis. H. pylori-negative gastritis is a consideration when an individual fulfill all four of these criteria (i) A negative triple staining of gastric mucosal biopsies (hematoxylin and eosin, Alcian blue stain and a modified silver stain), (ii) A negative H pylori culture, (iii) A negative IgG H. pylori serology, and (iv) No self-reported history of H. pylori treatment. In these patients, the cause of gastritis may relate to tobacco smoking, consumption of alcohol, and/or the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or steroids.

Other causes of gastritis include:

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as aspirin, ibuprofen and naproxen, are commonly used for pain relief, but they can also increase acidic gastric juices produced in the stomach. The increased stomach acid can inflame and wear down the stomach lining.

- Autoimmune gastritis. This is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by chronic atrophic gastritis and associated with raised serum anti-parietal and anti-intrinsic factor antibodies. The loss of parietal cells results in a reduction of gastric acid secretion, which is necessary for the absorption of inorganic iron. Therefore, iron deficiency is commonly a finding in patients with autoimmune gastritis. Iron deficiency in these patients usually precedes vitamin B12 deficiency. The disease is common in young women.

- Infection by organisms other than H. pylori such as Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare, enterococcal infection, Herpes simplex, and cytomegalovirus. Parasitic gastritis may result from cryptosporidium, Strongyloides stercoralis, or anisakiasis infection.

- Gastritis may result from bile acid reflux.

- Radiation gastritis.

- Crohn disease-associated gastritis. This is an uncommon cause of gastritis.

- Collagenous gastritis. This is a rare cause of gastritis. The disease characteristically presents with marked subepithelial collagen deposition accompanying with mucosal inflammatory infiltrate. The exact etiology and pathogenesis of collagenous gastritis are still unclear.

- Eosinophilic gastritis. This is another rare cause of gastritis. The disease could be part of the eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders which is characterized by the absence of known causes of eosinophilia (not secondary to an infection, systematic inflammatory disease, or any other causes to explain the eosinophilia).

- Sarcoidosis-associated gastritis. Sarcoidosis is a multisystemic disorder characterized by the presence of non-caseating granulomas. Although sarcoidosis can affect any body organ, the gastrointestinal tract, including the stomach, is rarely affected.

- Lymphocytic gastritis. This is a rare cause of gastritis. The cause of lymphocytic gastritis remains unestablished, but an association with H. pylori infection or celiac disease has been suggested.

- Ischemic gastritis. This is rare and associated with high mortality.

- Vasculitis-associated gastritis. Diseases causing systemic vasculitis can cause granulomatous infiltration of the stomach. An example is Granulomatosis with polyangiitis, formerly known as Wegner granulomatosis.

- Ménétrier disease. This disease is characterized by (i) Presence of large gastric mucosal folds in the body and fundus of the stomach, (ii) Massive foveolar hyperplasia of surface and glandular mucous cells, (iii) Protein-losing gastropathy, hypoalbuminemia, and edema in 20 to 100% of patients, and (iv) reduced gastric acid secretion because of loss of parietal cells 110.

- H. pylori-negative gastritis. The patients should fulfill all four of these criteria (i) A negative triple staining of gastric mucosal biopsies (hematoxylin and eosin, the Alcian blue stain and a modified silver stain), (ii) A negative H. pylori culture, (iii) A negative IgG H. pylori serology, and (iv) No self-reported history of H. pylori treatment. In these patients, the cause of gastritis may relate to tobacco smoking, consumption of alcohol, and/or the use of NSAIDs or steroids.

In the western population, there is evidence of declining incidence of infectious gastritis caused by Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) with an increasing prevalence of autoimmune gastritis 111. Autoimmune gastritis is more common in women and older people. The prevalence is estimated to be approximately 2% to 5%. However, available data do not have high reliability 112.

Chronic gastritis remains a relatively common disease in developing countries. The prevalence of H. pylori infection in children in the western population is approximately 10% but about 50% in developing countries 113, 114. In developing countries, the overall prevalence of H. pylori varies depending on geographical region and socioeconomic conditions. It is approximately 69% in Africa, 78% in South America, and 51% in Asia.

Socioeconomic and environmental hygiene are the essential factors in the transmission of H. pylori infection worldwide. These factors include family-bound hygiene, household density, and cooking habits. The pediatric origin of H. pylori infection is currently considered the primary determinant of H. pylori-associated gastritis in a community 115.

Risk factors for developing gastritis

Factors that increase your risk of gastritis include:

- Bacterial infection. Although infection with Helicobacter pylori is among the most common worldwide human infections, only some people with the infection develop gastritis or other upper gastrointestinal disorders. Doctors believe vulnerability to the bacterium could be inherited or could be caused by lifestyle choices, such as smoking and diet.

- Regular use of pain relievers. Pain relievers commonly referred to as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) — such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others) and naproxen sodium (Aleve, Anaprox DS) — can cause both acute gastritis and chronic gastritis. Using these pain relievers regularly or taking too much of these drugs may reduce a key substance that helps preserve the protective lining of your stomach.

- Older age. Older adults have an increased risk of gastritis because the stomach lining tends to thin with age and because older adults are more likely to have H. pylori infection or autoimmune disorders than younger people are.

- Excessive alcohol use. Alcohol can irritate and erode your stomach lining, which makes your stomach more vulnerable to digestive juices. Excessive alcohol use is more likely to cause acute gastritis.

- Stress. Severe stress due to major surgery, injury, burns or severe infections can cause acute gastritis.

- Cancer treatment. Chemotherapy drugs or radiation treatment can increase your risk of gastritis.

- Autoimmune gastritis. Autoimmune gastritis occurs when your body attacks the cells that make up your stomach lining. This reaction can wear away at your stomach’s protective barrier. Autoimmune gastritis is more common in people with other autoimmune disorders, including Hashimoto’s disease and type 1 diabetes. Autoimmune gastritis can also be associated with vitamin B-12 deficiency.

Other diseases and conditions. Gastritis may be associated with other medical conditions, including HIV/AIDS, Crohn’s disease, celiac disease, sarcoidosis and parasitic infections.

Gastritis prevention

Experts don’t know it is possible to stop gastritis from happening. But you may lower your risk of getting the disease by:

- Having good hygiene habits, especially washing your hands. This can keep you from getting the H. pylori bacteria.

- Not eating or drinking things that can irritate your stomach lining. This includes alcohol, caffeine, and spicy foods.

- Not taking medicines such as aspirin and over-the-counter pain and fever medicines (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or NSAIDS).

Gastritis diagnosis

To confirm the cause of the symptoms, your doctor is likely to talk to you about your medical history and examine you. They may also ask you to have some tests, such as blood tests, breath tests or stool tests. Which type of test you undergo depends on your situation.

Your doctor may also refer you to a specialist who is an expert in the digestive tract (gastroenterologist). Your gastroenterologist may order an upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy with biopsies or other tests to diagnose gastritis, find the cause, and check for complications. Other tests may include blood, stool, and breath tests and an upper GI series.

- Tests for H. pylori. Your doctor may recommend tests — such as a stool test or breath test — to determine whether you have the bacterium H. pylori. For the breath test, you drink a small glass of clear, tasteless liquid that contains radioactive carbon. H. pylori bacteria break down the test liquid in your stomach. Later, you blow into a bag, which is then sealed. If you’re infected with H. pylori, your breath sample will contain the radioactive carbon.

- Blood tests. You will have a test for H. pylori, a type of bacteria that may be in your stomach. Another test will check for anemia. You can get anemia when you don’t have enough red blood cells.

- Stool spectrum. This test checks to see if you have stomach bacteria that can cause gastritis. A small sample of your stool is collected and sent to a lab. Another stool specimen can check for blood in your stool which may be a sign of gastritis if there has been bleeding.

- Upper endoscopy also called EGD (esophagogastroduodenoscopy). During endoscopy, your doctor passes a flexible tube equipped with a camera at one end (endoscope) down your throat and into your esophagus, stomach and small intestine. Using the endoscope (a flexible tube with a tiny camera), your doctor looks for signs of inflammation and ulcers. This is usually done with some sedation. Depending on your age and medical history, your doctor may recommend endoscopy as a first test instead of testing for H. pylori. If a suspicious area is found, your doctor may remove small tissue samples (biopsy) for laboratory examination. A biopsy can also identify the presence of H. pylori in your stomach lining.

- X-ray of your upper digestive system. Sometimes called a barium swallow or upper GI (gastrointestinal) series, this series of X-rays creates images of your esophagus, stomach and and the first part of your small intestine (duodenum) to look for anything unusual. To make an ulcer more visible, you may swallow a white, metallic liquid (containing barium) that coats your digestive tract. Barium coats the organs so that they can be seen on the X-ray.

Gastritis treatment

Gastritis has several causes, including infection, taking some medications, and drinking too much alcohol. Treatment of gastritis depends on its cause. Your doctor may prescribe a mix of prescription and non-prescription (over the counter) medicines, and recommend lifestyle changes.

Common gastritis treatments are:

- Antibiotics to kill the H. pylori bacteria. If prescribed, it’s important you complete the full course

- Prescription medicines that reduce the amount of acid made in the stomach, called H2 blockers or proton pump inhibitors

- Over the counter antacids, which neutralize stomach acid (these should be taken separately from some other medicines — ask your pharmacist)

- Vitamin supplementation for autoimmune metaplastic atrophic gastritis

- Immunomodulatory therapy for autoimmune enteropathy

- Dietary modifications for eosinophilic gastritis.

It’s also important take your medicines as directed and to learn what triggers your symptoms.

Gastritis treatment at home

You can make some lifestyle changes to help improve your healing process, and reduce any further chances of irritation. You could try to:

- eat smaller meals more often

- avoid foods that can irritate your stomach, such as foods that are spicy, acidic (e.g. citrus and tomatoes), fried or fatty

- avoid alcohol and coffee

- avoid non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) — ask your doctor or pharmacist for alternative pain relievers. Ask your doctor whether acetaminophen (Tylenol, others) may be an option for you. This medication is less likely to aggravate your stomach problem.

- reduce stress

- stop smoking

Gastritis medications

Medications used to treat gastritis include:

- Antibiotic medications to kill H. pylori. For H. pylori in your digestive tract, your doctor may recommend a combination of antibiotics, such as clarithromycin (Biaxin XL) and amoxicillin (Amoxil, Augmentin, others) or metronidazole (Flagyl), to kill the bacterium. Be sure to take the full antibiotic prescription, usually for 7 to 14 days, along with medication to block acid production. Once treated, your doctor will retest you for H. pylori to be sure it has been destroyed.

- Medications that block acid production and promote healing. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) reduce acid by blocking the action of the parts of cells that produce acid. These drugs include the prescription and over-the-counter medications omeprazole (Prilosec), lansoprazole (Prevacid), rabeprazole (Aciphex), pantoprazole (Protonix) and others. Long-term use of proton pump inhibitors, particularly at high doses, may increase your risk of hip, wrist and spine fractures. Ask your doctor whether a calcium supplement may reduce this risk.

- Medications to reduce acid production. Acid blockers — also called histamine (H-2) blockers — reduce the amount of acid released into your digestive tract, which relieves gastritis pain and encourages healing. Available by prescription or over the counter, acid blockers include famotidine (Pepcid), cimetidine (Tagamet HB) and nizatidine (Axid AR).

- Medications that neutralize stomach acid. Your doctor may include an antacid in your drug regimen. Antacids neutralize existing stomach acid and can provide rapid pain relief. Side effects can include constipation or diarrhea, depending on the main ingredients. These help with immediate symptom relief but are generally not used as a primary treatment. Proton pump inhibitors and acid blockers are more effective and have fewer side effects.

H2 blockers

H2 blockers are medicines that reduce the amount of acid in the stomach. They include cimetidine, nizatidine and famotidine.

Proton pump inhibitors

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) also reduce the amount of acid in the stomach. They include omeprazole, esomeprazole, lansoprazole, rabeprazole and pantoprazole.

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are very safe and effective for short-term use. But long-term use isn’t recommended for most people, especially older people, because long-term use of proton pump inhibitors, particularly at high doses, may increase your risk of hip, wrist and spine fractures. If you have been taking proton pump inhibitors for a long time, talk to your doctor about whether you can reduce your dose.

Antacids

Antacids work by neutralizing stomach acid. Antacids neutralize stomach acid but they can stop some other medications from working properly. They can also cause constipation or diarrhea. Speak to your doctor or pharmacist about this.

Helicobacter Pylori treatment

If you have Helicobacter Pylori, this may be treated with antibiotics such as Amoxycillin, Clarithromycin, Metronidazole, Tinidazole or Tetracycline. You will need to take these as well as medication to reduce acid. It is important to take the medications as instructed by your doctor and make sure you finish the full course of antibiotics.

Gastritis diet

Researchers have not found that eating, diet, and nutrition play an important role in causing the majority of cases of gastritis.

Gastritis prognosis

Gastritis prognosis depends on the cause. For most people who undertake treatment, the symptoms do decrease but recurrences are common. Patients with H.pylori induced gastritis also have a small risk of developing gastric cancer in future.

- Sugano K, Tack J, Kuipers EJ, Graham DY, El-Omar EM, Miura S, Haruma K, Asaka M, Uemura N, Malfertheiner P; faculty members of Kyoto Global Consensus Conference. Kyoto global consensus report on Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Gut. 2015 Sep;64(9):1353-67. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309252[↩][↩][↩]

- Lee SY. Endoscopic gastritis, serum pepsinogen assay, and Helicobacter pylori infection. Korean J Intern Med. 2016 Sep;31(5):835-44. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2016.166[↩][↩]