Contents

Hepatocellular carcinoma

Hepatocellular carcinoma also known as primary liver cancer, is the most common cancer that starts in the liver. A cancer that starts in the liver is called primary liver cancer. There is more than one kind of primary liver cancer. On the other hand, metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma or secondary liver cancer, starts somewhere else and spreads to your liver. Most of the time when cancer is found in the liver it did not start there but has spread (metastasized) from somewhere else in the body, such as the pancreas, colon, stomach, breast, or lung. Because metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma has spread from its original (primary) site, it is called a secondary liver cancer. Metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma are named and treated based on their primary site (where they started). For example, cancer that started in the lung and spread to the liver is called lung cancer with spread to the liver, not liver cancer. It is also treated as lung cancer. In the United States and Europe, secondary (metastatic) liver tumors are more common than primary liver cancer. The opposite is true for many areas of Asia and Africa.

Hepatocellular carcinoma is a type of adenocarcinoma that occurs most often in people with chronic liver diseases, such as cirrhosis caused by hepatitis B or hepatitis C infection. Hepatocellular carcinoma is the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide.

Hepatocellular cancers can have different growth patterns:

- Some begin as a single tumor that grows larger. Only late in the disease does it spread to other parts of the liver.

- A second type seems to start as many small cancer nodules throughout the liver, not just a single tumor. This is seen most often in people with cirrhosis (chronic liver damage) and is the most common pattern seen in the United States.

Doctors can classify several subtypes of hepatocellular carcinoma. Most often these subtypes do not affect treatment or prognosis (outlook). But one of these subtypes, fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma, is important to recognize. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma is rare, making up less than 1% of hepatocellular carcinomas and is most often seen in women younger than age 35. Often the rest of the liver is not diseased. This subtype tends to have a better outlook than other forms of hepatocellular carcinoma.

Risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma or primary liver cancer include:

- Having hepatitis B or C

- Heavy alcohol use

- Having cirrhosis, or scarring of the liver

- Having hemochromatosis, an iron storage disease

- Obesity and diabetes

Hepatocellular carcinoma symptoms can include a lump or pain on the right side of your abdomen and yellowing of the skin. However, you may not have symptoms until the hepatocellular cancer is advanced. This makes it harder to treat. Doctors use tests that examine the liver and the blood to diagnose hepatocellular cancer. Treatment options include surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, or liver transplantation.

Your liver is one of the largest organs in your body. Your liver is the largest internal organ. It lies under your right ribs just beneath your right lung. Your liver has two lobes or sections and fills the upper right side of your abdomen inside the right rib cage.

You cannot live without your liver. It has many important functions. Six of the many important functions of your liver are:

- To filter harmful substances from the blood so they can be passed from the body in stools and urine.

- To make bile and delivers bile into the intestines to help digest fat that comes from food and absorb nutrients especially fats.

- To store glycogen (sugar), which the body uses for energy.

- It breaks down and stores many of the nutrients absorbed from the intestine that your body needs to function. Some nutrients must be changed (metabolized) in the liver before they can be used for energy or to build and repair body tissues.

- It makes most of the clotting factors that keep you from bleeding too much when you are cut or injured.

- It breaks down alcohol, drugs, and toxic wastes in the blood, which then pass from the body through urine and stool

Liver anatomy

Your liver is the largest organ inside your body, weighing about 1.4 kg (3 pounds) in an average adult. The liver is in the right upper quadrant of the abdominal cavity, just inferior to the diaphragm in the right superior part of the abdominal cavity and under your right ribs just beneath your right lung – filling much of the right hypochondriac and epigastric regions and extending into the left hypochondriac region. The liver is partially surrounded by the ribs, and extends from the level of the fifth intercostal space to the lower margin of the right rib cage, which protects this highly vascular organ from blows that could rupture it. The liver is shaped like a wedge, the wide base of which faces right and the narrow apex of which lies just inferior to the level of the left nipple. The reddish-brown liver is well supplied with blood vessels.

A fibrous capsule encloses the liver, and ligaments divide the organ into a large right lobe and a smaller left lobe (Figure 2).

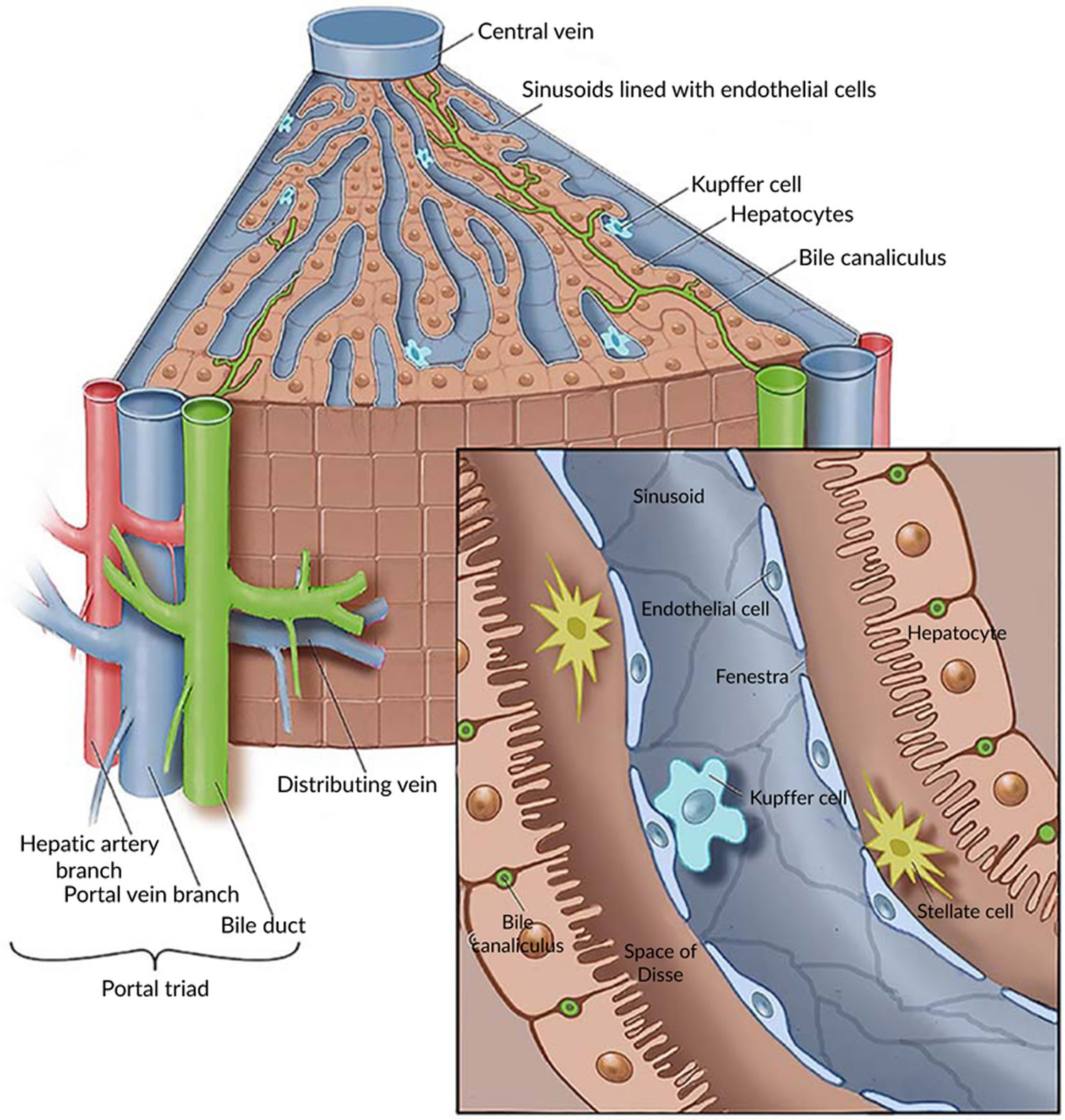

The liver also has two minor lobes, the quadrate lobe and the caudate lobe. Each lobe is separated into many tiny hepatic lobules, the liver’s functional units (Figure 3). A lobule consists of many hepatic cells radiating outward from a central vein. Blood-filled channels called hepatic sinusoids separate platelike groups of these cells from each other. Blood from the digestive tract, carried in the hepatic portal vein, brings newly absorbed nutrients into the sinusoids and nourishes the hepatic cells.

Large phagocytic macrophages called Kupffer cells are fixed to the inner linings of the hepatic sinusoids. They remove bacteria or other foreign particles that enter the blood through the intestinal wall, and are brought to the liver via the hepatic portal vein. Blood passes from these sinusoids into the central veins of the hepatic lobules and exits the liver via the hepatic veins.

Within the hepatic lobules are many fine bile canaliculi, which carry secretions from hepatic cells to bile ductules. The ductules of neighboring lobules converge to ultimately form the hepatic ducts. These ducts merge, in turn, to form the common hepatic duct.

Figure 1. Location of the human liver

Figure 2. Liver anatomy

Figure 3. Liver lobule

Footnote: (a) Cross section of a hepatic lobule. (b) Enlarged longitudinal section of a hepatic lobule. (c) Light micrograph of hepatic lobules in cross section.

Figure 4. Human liver microscopic anatomy

Liver functions

Amazingly versatile, your liver performs over 500 functions. Its digestive function is to produce bile, a green alkaline liquid that is stored in the gallbladder and secreted into the duodenum. Bile salts emulsify fats in the small intestine; that is, they break up fatty nutrients into tiny particles, just as dish detergent breaks up a pool of fat drippings in a roasting pan. These smaller particles are more accessible to digestive enzymes from the pancreas. The liver also performs many metabolic functions and you cannot live without your liver:

- Picks up glucose from nutrient-rich blood returning from the alimentary canal and stores this carbohydrate as glycogen for subsequent use by the body.

- Processes fats and amino acids and stores certain vitamins.

- Detoxifies many poisons and drugs in the blood.

- Makes the blood proteins.

- It breaks down and stores many of the nutrients absorbed from the intestine that your body needs to function. Some nutrients must be changed (metabolized) in the liver before they can be used for energy or to build and repair body tissues.

- It makes most of the clotting factors that keep you from bleeding too much when you are cut or injured.

- It secretes bile into the intestines to help absorb nutrients (especially fats).

- It breaks down alcohol, drugs, and toxic wastes in the blood, which then pass from the body through urine and stool.

Almost all of these functions are carried out by a type of cell called a hepatocyte or simply a liver cell.

The liver carries on many important metabolic activities. The liver plays a key role in carbohydrate metabolism by helping maintain concentration of blood glucose within the normal range. Liver cells responding to the hormone insulin lower the blood glucose level by polymerizing glucose to glycogen. Liver cells responding to the hormone glucagon raise the blood glucose level by breaking down glycogen to glucose or by converting noncarbohydrates into glucose.

The liver’s effects on lipid metabolism include oxidizing (breaking down) fatty acids at an especially high rate; synthesizing lipoproteins, phospholipids, and cholesterol; and converting excess portions of carbohydrate molecules into fat molecules. The blood transports fats synthesized in the liver to adipose tissue for storage.

Other liver functions concern protein metabolism. They include deaminating amino acids; forming urea; synthesizing plasma proteins such as clotting factors; and converting certain amino acids into other amino acids.

The liver also stores many substances, including glycogen, iron, and vitamins A, D, and B12. In addition, macrophages in the liver help destroy damaged red blood cells and phagocytize foreign antigens. The liver also removes toxic substances such as alcohol and certain drugs from blood (detoxification). Table 1 summarizes the major functions of the liver.

Table 1. Major Functions of the Liver

| General Function | Specific Function |

| Carbohydrate metabolism | Polymerizes glucose to glycogen; breaks down glycogen to glucose; converts noncarbohydrates to glucose |

| Lipid metabolism | Oxidizes fatty acids; synthesizes lipoproteins, phospholipids, and cholesterol; converts excess portions of carbohydrate molecules into fats |

| Protein metabolism | Deaminates amino acids; forms urea; synthesizes plasma proteins; converts certain amino acids into other amino acids |

| Storage | Stores glycogen, iron, and vitamin A, vitamin D and vitamin B12 |

| Blood filtering | Removes damaged red blood cells and foreign substances by phagocytosis |

| Detoxification | Removes toxins from blood |

| Secretion | Produces and secretes bile |

The Bile

Bile is a yellowish-green liquid continuously secreted from hepatic cells. In addition to water, bile contains bile salts, bile pigments (bilirubin and biliverdin), cholesterol, and electrolytes. Of these, bile salts are the most abundant and are the only bile components that have a digestive function.

Bile pigments are breakdown products of hemoglobin from red blood cells and are normally secreted in the bile.

Jaundice, a yellowing of the skin and mucous membranes due to accumulation of bile pigment, has several causes. In obstructive jaundice bile ducts are blocked, perhaps by gallstones or tumors. In hepatocellular jaundice the liver is diseased, as in cirrhosis or hepatitis. In hemolytic jaundice red blood cells are destroyed too rapidly, as happens with an incompatible blood transfusion or a blood infection.

Regulation of Bile Release

Normally bile does not enter the duodenum until cholecystokinin stimulates the gallbladder to contract. The intestinal mucosa releases this hormone in response to proteins and fats in the small intestine. The hepatopancreatic sphincter usually remains contracted until a peristaltic wave in the duodenal wall approaches it. Then the sphincter relaxes, and bile is squirted into the duodenum.

Functions of Bile Salts

Bile salts aid digestive enzymes. Bile salts affect fat globules (clumped molecules of fats) much like a soap or detergent would affect them. That is, bile salts break fat globules into smaller droplets that are more soluble in water. This action, called emulsification, greatly increases the total surface area of the fatty substance. The resulting fat droplets disperse in water. Fat-splitting enzymes (lipases) can then digest the fat molecules more effectively. Bile salts also enhance absorption of fatty acids, cholesterol, and the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K.

Low levels of bile salts result in poor lipid absorption and vitamin deficiencies.

The Gallbladder

The gallbladder is a pear-shaped sac in a depression on the liver’s inferior surface. The gallbladder is lined with epithelial cells and has a strong layer of smooth muscle in its wall. The gallbladder stores bile between meals, reabsorbs water to concentrate bile, and contracts to release bile into the small intestine. It connects to the cystic duct, which in turn joins the common hepatic duct.

The common hepatic duct and cystic duct join to form the bile duct (common bile duct). It leads to the duodenum where the hepatopancreatic sphincter guards its exit. Because this sphincter normally remains contracted, bile collects in the bile duct. It backs up into the cystic duct and flows into the gallbladder, where it is stored.

A liver function important to digestion is bile secretion.

Hepatocellular carcinoma causes

Although several risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma are known, exactly how these may lead normal liver cells to become cancerous is only partially understood. Some of these risk factors affect the DNA of cells in the liver, which can result in abnormal cell growth and may cause cancers to form.

DNA is the chemical in your cells that carries our genes which control how your cells function. Some genes control when cells grow, divide into new cells, and die.

- Genes that help cells to grow and divide and stay alive are called oncogenes.

- Genes that keep cell division under control, repair mistakes in DNA, or cause cells to die at the right time are called tumor suppressor genes.

Cancers can be caused by DNA changes (mutations) that turn on oncogenes or turn off tumor suppressor genes. Several different genes usually need to have changes for a cell to become cancerous.

Certain chemicals that cause hepatocellular carcinoma, such as aflatoxins, are known to damage the DNA in liver cells. For example, studies have shown that aflatoxins can damage the TP53 tumor suppressor gene, which normally works to prevent cells from growing too much. Damage to the TP53 gene can lead to increased growth of abnormal cells and formation of cancers.

Hepatitis viruses can also change DNA when they infect liver cells. In some patients, the virus’s DNA can insert itself into a liver cell’s DNA, where it may turn on the cell’s oncogenes.

Liver cancer clearly has many different causes, and there are undoubtedly many different genes involved in its development. It is hoped that a more complete understanding of how hepatocellular carcinomas develop will help doctors find ways to better prevent and treat them.

Risk factors of hepatocellular carcinoma

Anything that increases your chance of getting a disease is called a risk factor. Having a risk factor does not mean that you will get cancer; not having risk factors doesn’t mean that you will not get cancer. The risk of hepatocellular carcinoma, the most common type of liver cancer, is higher in people with long-term liver diseases. It’s also higher if the liver is scarred by infection with hepatitis B or hepatitis C. Hepatocellular carcinoma is more common in people who drink large amounts of alcohol and who have an accumulation of fat in the liver. Talk to your doctor if you think you may be at risk for liver cancer.

Risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma include the following:

- Having hepatitis B or hepatitis C infection. Having both hepatitis B and hepatitis C increases the risk even more. In the US, infection with hepatitis C is the more common cause of hepatocellular carcinoma, while in Asia and developing countries, hepatitis B is more common. People infected with both viruses have a high risk of developing chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. The risk is even higher if they are heavy drinkers (at least 6 alcoholic drinks a day). hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus can spread from person to person through sharing contaminated needles (such as in drug use), unprotected sex, or childbirth. They can also be passed on through blood transfusions, although this is very rare in the United States since blood products are tested for these viruses. In developing countries, children sometimes contract hepatitis B infection from prolonged contact with family members who are infected.

- Having cirrhosis. Cirrhosis is a disease in which liver cells become damaged and are replaced by scar tissue. People with cirrhosis have an increased risk of liver cancer. Most (but not all) people who develop liver cancer already have some evidence of cirrhosis. There are several possible causes of cirrhosis. Most cases in the United States occur in people who abuse alcohol or have chronic hepatitis B virus or hepatitis C virus infections.

- Heavy alcohol use. Heavy alcohol use and having hepatitis B infection increases the risk even more. Alcohol abuse is a leading cause of cirrhosis in the US, which in turn is linked with an increased risk of liver cancer.

- Eating foods tainted with aflatoxin (poison from a fungus that can grow on foods, such as peanuts, wheat, soybeans, ground nuts, corn, and rice, that have not been stored properly). Storage in a moist, warm environment can lead to the growth of this fungus. Although this can occur almost anywhere in the world, it is more common in warmer and tropical countries. Developed countries, such as the US and those in Europe, test foods for levels of aflatoxins. Long-term exposure to aflatoxins is a major risk factor for liver cancer. The risk is increased even more in people with hepatitis B or C infections.

- Having nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), a condition in which fat builds up in the liver and may progress to inflammation of the liver and liver cell damage. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is a common condition in obese people. People with a non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) might go on to develop cirrhosis.

- Having primary biliary cirrhosis. Primary biliary cirrhosis is an autoimmune disorder. That means your body’s immune system mistakenly attacks healthy tissue. The disease most often affects middle-aged women. In primary biliary cirrhosis the bile ducts in the liver are damaged and even destroyed which can lead to cirrhosis. People with advanced primary biliary cirrhosis have a high risk of liver cancer.

- Using tobacco, such as cigarette smoking. Smoking increases the risk of liver cancer. Former smokers have a lower risk than current smokers, but both groups have a higher risk than those who never smoked.

- Being obese (very overweight) increases the risk of developing liver cancer. This is probably because it can result in fatty liver disease and cirrhosis.

- Type 2 diabetes has been linked with an increased risk of liver cancer, usually in patients who also have other risk factors such as heavy alcohol use and/or chronic viral hepatitis. This risk may also be increased because people with type 2 diabetes tend to be overweight or obese, which in turn can cause liver problems.

- Exposure to vinyl chloride and thorium dioxide (Thorotrast). Exposure to these chemicals raises the risk of angiosarcoma of the liver. It also increases the risk of developing cholangiocarcinoma and hepatocellular cancer, but to a far lesser degree. Vinyl chloride is a chemical used in making some kinds of plastics. Thorotrast is a chemical that in the past was injected into some patients as part of certain x-ray tests. When the cancer-causing properties of these chemicals were recognized, steps were taken to eliminate them or minimize exposure to them. Thorotrast is no longer used, and exposure of workers to vinyl chloride is strictly regulated.

- Anabolic steroids use. Anabolic steroids are male hormones used by some athletes to increase their strength and muscle mass. Long-term anabolic steroid use can slightly increase the risk of hepatocellular cancer. Cortisone-like steroids, such as hydrocortisone, prednisone, and dexamethasone, do not carry this same risk.

- Having certain inherited or rare disorders that damage the liver, including the following:

- Hereditary hemochromatosis, an inherited disorder in which the body stores more iron than it needs. The extra iron is mostly stored in the liver, heart, pancreas, skin, and joints. If enough iron builds up in the liver, it can lead to cirrhosis and liver cancer.

- Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, an inherited disorder that can cause liver and lung disease.

- Glycogen storage disease, an inherited disorder in which there are problems with how a form of glucose (sugar) called glycogen is stored and used in the body.

- Porphyria cutanea tarda, a rare disorder that affects the skin and causes painful blisters on parts of the body that are exposed to the sun, such as the hands, arms, and face. Liver problems can also occur.

- Wilson disease, a rare inherited disorder in which the body stores more copper than it needs. The extra copper is stored in the liver, brain, eyes, and other organs.

- Tyrosinemia. Tyrosinemia is a genetic disorder characterized by disruptions in the multistep process that breaks down the amino acid tyrosine, a building block of most proteins. If untreated, tyrosine and its byproducts build up in tissues and organs, which can lead to serious health problems.

Older age is the main risk factor for most cancers. The chance of getting cancer increases as you get older.

Hepatocellular carcinoma prevention

Many hepatocellular carcinomas could be prevented by reducing exposure to known risk factors for this disease.

Avoid and treat hepatitis B and C infections

Worldwide, the most significant risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma is chronic infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV). These viruses can spread from person to person through sharing contaminated needles (such as in drug use) through unprotected sex, and through childbirth, so some hepatocellular carcinomas may be avoided by not sharing needles and by using safer sex practices (such as always using condoms).

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that all children, as well as adults at risk get the hepatitis B virus vaccine to reduce the risk of hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. There is no vaccine for hepatitis C virus. Preventing hepatitis C virus infection, as well as hepatitis B virus infection in people who have not been immunized, is based on understanding how these infections occur.

Blood transfusions were once a major source of hepatitis infection as well. But because blood banks in the United States test donated blood to look for these viruses, the risk of getting a hepatitis infection from a blood transfusion is extremely low.

People at high risk for hepatitis B virus or hepatitis C virus should be tested for these infections so they can be watched for liver disease and treated if needed.

The CDC recommends that you get tested for hepatitis C virus if any of the following are true:

- You were born from 1945 through 1965 (this is because most of the people in the US that are infected with hepatitis C virus were born in these years)

- You ever injected drugs (even just once or a long time ago)

- You needed medicine for a blood clotting problem before 1987

- You received a blood transfusion or organ transplant before July 1992 (when blood and organs started being screened for hepatitis C virus)

- You were or are on long-term hemodialysis

- You are infected with HIV

- You might have been exposed to Hepatitis C in the last 6 months through sex or sharing needles during drug use

Treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus infection can eliminate the virus in many people and may lower the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma.

A number of drugs are used to treat chronic hepatitis B virus. These drugs reduce the number of viruses in the blood and lessen liver damage. Although the drugs don’t cure the disease, they lower the risk of cirrhosis and may lower the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma, as well.

Limit alcohol and tobacco use

Drinking alcohol can lead to cirrhosis, which in turn, can lead to hepatocellular carcinoma. Not drinking alcohol or drinking in moderation could help prevent hepatocellular carcinoma.

Since smoking also increases the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma, not smoking will also prevent some of these cancers. If you smoke, quitting will help lower your risk of this cancer, as well as many other cancers and life-threatening diseases.

Stay at a healthy weight

Avoiding obesity might be another way to help protect against hepatocellular carcinoma. People who are obese are more likely to have fatty liver disease and diabetes, both of which have been linked to hepatocellular carcinoma.

Limit exposure to cancer-causing chemicals

Changing the way certain grains are stored in tropical and subtropical countries could reduce exposure to cancer-causing substances such as aflatoxins. Many developed countries already have regulations to prevent and monitor grain contamination.

Treat diseases that increase hepatocellular carcinoma risk

Certain inherited diseases can cause cirrhosis of the liver, increasing a person’s risk for hepatocellular carcinoma. Finding and treating these diseases early in life could lower this risk. For example, all children in families with hemochromatosis should be screened for the disease and treated if they have it. Treatment regularly removes small amounts of blood to lower the amount of excess iron in the body.

Hepatocellular carcinoma symptoms

These and other signs and symptoms may be caused by hepatocellular carcinoma or by other conditions. Check with your doctor if you have any of the following:

- A hard lump on the right side just below the rib cage.

- Discomfort in the upper abdomen on the right side.

- A swollen abdomen.

- Pain near the right shoulder blade or in the back.

- Jaundice (yellowing of the skin and whites of the eyes).

- Easy bruising or bleeding.

- Unusual tiredness or weakness.

- Nausea and vomiting.

- Loss of appetite or feelings of fullness after eating a small meal.

- Weight loss for no known reason.

- Pale, chalky bowel movements and dark urine.

- Fever.

People who have chronic hepatitis or cirrhosis might feel worse than usual or might just have changes in lab test results, such as liver function tests or alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels.

Some liver tumors make hormones that act on organs other than the liver. These hormones may cause:

- High blood calcium levels (hypercalcemia), which can cause nausea, confusion, constipation, weakness, or muscle problems

- Low blood sugar levels (hypoglycemia), which can cause fatigue or fainting

- Breast enlargement (gynecomastia) and/or shrinkage of the testicles in men

- High counts of red blood cells (erythrocytosis) which can cause someone to look red and flushed

- High cholesterol levels

Hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosis

Tests that examine the liver and the blood are used to detect (find) and diagnose hepatocellular carcinoma.

The following tests and procedures may be used:

- Physical exam and history: An exam of the body to check general signs of health, including checking for signs of disease, such as lumps or anything else that seems unusual. A history of the patient’s health habits and past illnesses and treatments will also be taken.

- Serum tumor marker test: A procedure in which a sample of blood is examined to measure the amounts of certain substances released into the blood by organs, tissues, or tumor cells in the body. Certain substances are linked to specific types of cancer when found in increased levels in the blood. These are called tumor markers. An increased level of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) in the blood may be a sign of liver cancer. Other cancers and certain noncancerous conditions, including cirrhosis and hepatitis, may also increase AFP levels. Sometimes the AFP level is normal even when there is liver cancer.

- Liver function tests: A procedure in which a blood sample is checked to measure the amounts of certain substances released into the blood by the liver. A higher than normal amount of a substance can be a sign of liver cancer.

- CT scan (CAT scan): A procedure that makes a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body, such as the abdomen, taken from different angles. The pictures are made by a computer linked to an x-ray machine. A dye may be injected into a vein or swallowed to help the organs or tissues show up more clearly. This procedure is also called computed tomography, computerized tomography, or computerized axial tomography. Images may be taken at three different times after the dye is injected, to get the best picture of abnormal areas in the liver. This is called triple-phase CT. A spiral or helical CT scan makes a series of very detailed pictures of areas inside the body using an x-ray machine that scans the body in a spiral path.

- MRI (magnetic resonance imaging): A procedure that uses a magnet, radio waves, and a computer to make a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body, such as the liver. This procedure is also called nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (NMRI). To create detailed pictures of blood vessels in and near the liver, dye is injected into a vein. This procedure is called MRA (magnetic resonance angiography). Images may be taken at three different times after the dye is injected, to get the best picture of abnormal areas in the liver. This is called triple-phase MRI.

- Ultrasound exam: A procedure in which high-energy sound waves (ultrasound) are bounced off internal tissues or organs and make echoes. The echoes form a picture of body tissues called a sonogram. The picture can be printed to be looked at later.

- Biopsy: The removal of cells or tissues so they can be viewed under a microscope by a pathologist to check for signs of cancer. Procedures used to collect the sample of cells or tissues include the following:

- Fine-needle aspiration biopsy: The removal of cells, tissue or fluid using a thin needle.

- Core needle biopsy: The removal of cells or tissue using a slightly wider needle.

- Laparoscopy: A surgical procedure to look at the organs inside the abdomen to check for signs of disease. Small incisions (cuts) are made in the wall of the abdomen and a laparoscope (a thin, lighted tube) is inserted into one of the incisions. Another instrument is inserted through the same or another incision to remove the tissue samples.

A biopsy is not always needed to diagnose adult primary liver cancer.

Hepatocellular carcinoma stages

Liver cancer is usually staged based on the results of the physical exam, biopsies, and imaging tests (ultrasound, CT or MRI scan, etc.), also called a clinical stage. If surgery is done, the pathologic stage (also called the surgical stage) is determined by examining tissue removed during an operation. Cancer staging can be complex, so ask your doctor to explain it to you in a way you understand.

There are several staging systems for liver cancer and not all doctors use the same system. The Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer Staging System may be used to stage adult hepatocellular carcinoma.

The Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer Staging System is widely used and is used to predict the patient’s chance of recovery and to plan treatment, based on the following:

- Whether the cancer has spread within the liver or to other parts of the body.

- How well the liver is working.

- The general health and wellness of the patient.

- The symptoms caused by the cancer.

The Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer Staging System has five stages:

- Stage 0: Very early

- Stage A: Early

- Stage B: Intermediate

- Stage C: Advanced

- Stage D: End-stage

The following groups are used to plan treatment.

Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stages 0, A, and B

- Treatment to cure the cancer is given for Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stages 0, A, and B.

Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stages C and D

- Treatment to relieve the symptoms caused by liver cancer and improve the patient’s quality of life is given for Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stages C and D. Treatments are not likely to cure the cancer.

The staging system most often used in the United States for liver cancer is the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM system, which is based on 3 key pieces of information:

- The extent (size) of the tumor (T): How large has the cancer grown? Is there more than one tumor in the liver? Has the cancer reached nearby structures like the veins in the liver?

- The spread to nearby lymph nodes (N): Has the cancer spread to nearby lymph nodes?

- The spread (metastasis) to distant sites (M): Has the cancer spread to distant lymph nodes or distant organs such as the bones or lungs?

The system described below is the most recent American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) system, effective January 2018.

Numbers or letters after T, N, and M provide more details about each of these factors. Higher numbers mean the cancer is more advanced. Once a person’s T, N, and M categories have been determined, this information is combined in a process called stage grouping to assign an overall stage.

Table 1. American Joint Committee on Cancer liver cancer staging system

| American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Stage | Stage grouping | Stage description* |

|---|---|---|

| 1A | T1a N0 M0 | A single tumor 2 cm (4/5 inch) or smaller that hasn’t grown into blood vessels (T1a). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| 1B | T1b N0 M0 | A single tumor larger than 2cm (4/5 inch) that hasn’t grown into blood vessels (T1b). The cancer has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| 2 | T2 N0 M0 | Either a single tumor larger than 2 cm (4/5 inch) that has grown into blood vessels, OR more than one tumor but none larger than 5 cm (about 2 inches) across (T2). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| 3A

| T3 N0 M0 | More than one tumor, with at least one tumor larger than 5 cm across (T3). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| 3B | T4 N0 M0 | At least one tumor (any size) that has grown into a major branch of a large vein of the liver (the portal or hepatic vein) (T4). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| 4A | Any T N1 M0 | A single tumor or multiple tumors of any size (Any T) that has spread to nearby lymph nodes (N1) but not to distant sites (M0). |

| 4B | Any T Any N M1 | A single tumor or multiple tumors of any size (any T). It might or might not have spread to nearby lymph nodes (any N). It has spread to distant organs such as the bones or lungs (M1). |

Footnote:

* The following additional categories are not listed on the table above:

- TX: Main tumor cannot be assessed due to lack of information.

- T0: No evidence of a primary tumor.

- NX: Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed due to lack of information.

Liver cancer classification

Formal staging systems (such as those described above) can often help doctors determine a patient’s prognosis (outlook). But for treatment purposes, doctors often classify hepatocellular carcinomas more simply, based on whether or not they can be cut out (resected) completely. Resectable means able to be removed by surgery.

Potentially resectable or transplantable cancers

If the patient is healthy enough for surgery, these cancers can be completely removed by surgery or treated with a liver transplant. . This would include most stage I and some stage II cancers in the TNM system, in patients who do not have cirrhosis or other serious medical problems. Only a small number of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma have this type of tumor.

Unresectable cancers

Cancers that have not spread to the lymph nodes or distant organs but cannot be completely removed by surgery are classified as unresectable. This includes cancers that have spread throughout the liver or can’t be removed safely because they are close to the area where the liver meets the main arteries, veins, and bile ducts.

Inoperable cancer with only local disease

The cancer is small enough and in the right place to be removed but you aren’t healthy enough for surgery. Often this is because the non-cancerous part of your liver is not healthy (because of cirrhosis, for example), and if the cancer is removed, there might not be enough healthy liver tissue left for it to function properly. It could also mean that you have serious medical problems that make surgery unsafe.

Advanced (metastatic) cancers

Cancers that have spread to lymph nodes or other organs are classified as advanced. These would include stages IVA and IVB cancers in the TNM system. Most advanced hepatocellular carcinomas cannot be treated with surgery.

Hepatocellular carcinoma treatment

Patients with hepatocellular carcinoma are treated by a team of specialists who are experts in treating hepatocellular carcinoma. The medical oncologist may refer the patient to other health professionals who have special training in treating patients with liver cancer. These may include the following specialists:

- Hepatologist (specialist in liver disease).

- Surgical oncologist.

- Transplant surgeon.

- Radiation oncologist.

- Interventional radiologist (a specialist who diagnoses and treats diseases using imaging and the smallest incisions possible).

- Pathologist.

There are different types of treatment for patients with adult primary hepatocellular carcinoma. Some treatments are standard (the currently used treatment), and some are being tested in clinical trials. A treatment clinical trial is a research study meant to help improve current treatments or obtain information on new treatments for patients with cancer. When clinical trials show that a new treatment is better than the standard treatment, the new treatment may become the standard treatment. Patients may want to think about taking part in a clinical trial. Some clinical trials are open only to patients who have not started treatment.

Eight types of standard treatment are used:

Surveillance

Surveillance for lesions smaller than 1 centimeter found during screening. Follow-up every three months is common.

Surgery

A partial hepatectomy (surgery to remove the part of the liver where cancer is found) may be done. A wedge of tissue, an entire lobe, or a larger part of the liver, along with some of the healthy tissue around it is removed. The remaining liver tissue takes over the functions of the liver and may regrow.

Liver transplant

In a liver transplant, the entire liver is removed and replaced with a healthy donated liver. A liver transplant may be done when the disease is in the liver only and a donated liver can be found. If the patient has to wait for a donated liver, other treatment is given as needed.

Ablation therapy

Ablation therapy removes or destroys tissue. Different types of ablation therapy are used for hepatocellular carcinoma:

- Radiofrequency ablation: The use of special needles that are inserted directly through the skin or through an incision in the abdomen to reach the tumor. High-energy radio waves heat the needles and tumor which kills cancer cells.

- Microwave therapy: A type of treatment in which the tumor is exposed to high temperatures created by microwaves. This can damage and kill cancer cells or make them more sensitive to the effects of radiation and certain anticancer drugs.

- Percutaneous ethanol injection: A cancer treatment in which a small needle is used to inject ethanol (pure alcohol) directly into a tumor to kill cancer cells. Several treatments may be needed. Usually local anesthesia is used, but if the patient has many tumors in the liver, general anesthesia may be used.

- Cryoablation: A treatment that uses an instrument to freeze and destroy cancer cells. This type of treatment is also called cryotherapy and cryosurgery. The doctor may use ultrasound to guide the instrument.

- Electroporation therapy: A treatment that sends electrical pulses through an electrode placed in a tumor to kill cancer cells. Electroporation therapy is being studied in clinical trials.

Embolization therapy

Embolization therapy is the use of substances to block or decrease the flow of blood through the hepatic artery to the tumor. When the tumor does not get the oxygen and nutrients it needs, it will not continue to grow. Embolization therapy is used for patients who cannot have surgery to remove the tumor or ablation therapy and whose tumor has not spread outside the liver.

The liver receives blood from the hepatic portal vein and the hepatic artery. Blood that comes into the liver from the hepatic portal vein usually goes to the healthy liver tissue. Blood that comes from the hepatic artery usually goes to the tumor. When the hepatic artery is blocked during embolization therapy, the healthy liver tissue continues to receive blood from the hepatic portal vein.

There are two main types of embolization therapy:

- Transarterial embolization (TAE): A small incision (cut) is made in the inner thigh and a catheter (thin, flexible tube) is inserted and threaded up into the hepatic artery. Once the catheter is in place, a substance that blocks the hepatic artery and stops blood flow to the tumor is injected.

- Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE): This procedure is like transarterial embolization except an anticancer drug is also given. The procedure can be done by attaching the anticancer drug to small beads that are injected into the hepatic artery or by injecting the anticancer drug through the catheter into the hepatic artery and then injecting the substance to block the hepatic artery. Most of the anticancer drug is trapped near the tumor and only a small amount of the drug reaches other parts of the body. This type of treatment is also called chemoembolization.

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy is a treatment that uses drugs or other substances to identify and attack specific cancer cells without harming normal cells. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors are a type of targeted therapy used in the treatment of adult hepatocellular carcinoma.

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors are small-molecule drugs that go through the cell membrane and work inside cancer cells to block signals that cancer cells need to grow and divide. Some tyrosine kinase inhibitors also have angiogenesis inhibitor effects. Sorafenib, lenvatinib, and regorafenib are types of tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is a treatment that uses the patient’s immune system to fight cancer. Substances made by the body or made in a laboratory are used to boost, direct, or restore the body’s natural defenses against cancer. This type of cancer treatment is also called biotherapy or biologic therapy.

Immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy is a type of immunotherapy.

Immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: PD-1 is a protein on the surface of T cells that helps keep the body’s immune responses in check. When PD-1 attaches to another protein called PDL-1 on a cancer cell, it stops the T cell from killing the cancer cell. PD-1 inhibitors attach to PDL-1 and allow the T cells to kill cancer cells. Nivolumab is a type of immune checkpoint inhibitor.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is a cancer treatment that uses high-energy x-rays or other types of radiation to kill cancer cells or keep them from growing. There are two types of radiation therapy:

- External radiation therapy uses a machine outside the body to send radiation toward the cancer. Certain ways of giving radiation therapy can help keep radiation from damaging nearby healthy tissue. These types of external radiation therapy include the following:

- Conformal radiation therapy: Conformal radiation therapy is a type of external radiation therapy that uses a computer to make a 3-dimensional (3-D) picture of the tumor and shapes the radiation beams to fit the tumor. This allows a high dose of radiation to reach the tumor and causes less damage to nearby healthy tissue.

- Stereotactic body radiation therapy: Stereotactic body radiation therapy is a type of external radiation therapy. Special equipment is used to place the patient in the same position for each radiation treatment. Once a day for several days, a radiation machine aims a larger than usual dose of radiation directly at the tumor. By having the patient in the same position for each treatment, there is less damage to nearby healthy tissue. This procedure is also called stereotactic external-beam radiation therapy and stereotaxic radiation therapy.

- Proton beam radiation therapy: Proton-beam therapy is a type of high-energy, external radiation therapy. A radiation therapy machine aims streams of protons (tiny, invisible, positively-charged particles) at the cancer cells to kill them. This type of treatment causes less damage to nearby healthy tissue.

- Internal radiation therapy uses a radioactive substance sealed in needles, seeds, wires, or catheters that are placed directly into or near the cancer.

The way the radiation therapy is given depends on the type and stage of the cancer being treated. External radiation therapy is used to treat adult hepatocellular carcinoma.

Clinical trials

For some patients, taking part in a clinical trial may be the best treatment choice. Clinical trials are part of the cancer research process. Clinical trials are done to find out if new cancer treatments are safe and effective or better than the standard treatment.

Many of today’s standard treatments for cancer are based on earlier clinical trials. Patients who take part in a clinical trial may receive the standard treatment or be among the first to receive a new treatment.

Patients who take part in clinical trials also help improve the way cancer will be treated in the future. Even when clinical trials do not lead to effective new treatments, they often answer important questions and help move research forward.

Information about clinical trials is available from the National Cancer Institute website (https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/clinical-trials/search). Use the National Cancer Institute clinical trial search to find National Cancer Institute-supported cancer clinical trials that are accepting patients. You can search for trials based on the type of cancer, the age of the patient, and where the trials are being done.

Life expectancy hepatocellular carcinoma

Life expectancy of hepatocellular carcinoma depends on the following:

- The stage of the cancer (the size of the tumor, whether it affects part or all of the liver, or has spread to other places in the body).

- How well your liver is working.

- Your general health, including whether there is cirrhosis of the liver.

Survival rates can give you an idea of what percentage of people with the same type and stage of cancer are still alive a certain length of time (usually 5 years) after they were diagnosed. They can’t tell you how long you will live, but they may help give you a better understanding of how likely it is that your treatment will be successful.

Keep in mind that survival rates are estimates and are often based on previous outcomes of large numbers of people who had a specific cancer, but they can’t predict what will happen in any particular person’s case. These statistics can be confusing and may lead you to have more questions. Talk with your doctor about how these numbers may apply to you, as he or she is familiar with your situation.

A relative survival rate compares people with the same type and stage of liver cancer to people in the overall population. For example, if the 5-year relative survival rate for a specific stage of liver cancer is 30%, it means that people who have that cancer are, on average, about 30% as likely as people who don’t have that cancer to live for at least 5 years after being diagnosed.

In general, survival rates are higher for people who can have surgery to remove their cancer, regardless of the stage. For example, studies have shown that patients with small, resectable (removable) tumors who do not have cirrhosis or other serious health problems are likely to do well if their cancers are removed. For people with early-stage liver cancers who have a liver transplant, the 5-year survival rate is in the range of 60% to 70%.

Table 2. 5-year relative survival rates for liver cancer (Based on people diagnosed with cancers of the liver (or intrahepatic bile ducts) between 2008 and 2014.)

| Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) stage | 5-year relative survival rate |

|---|---|

| Localized | 31% |

| Regional | 11% |

| Distant | 2% |

| All SEER stages combined | 18% |

Footnote:

- Localized: There is no sign that the cancer has spread outside of the liver. This includes American Joint Committee on Cancer stage I, II, and some stage III cancers. This includes a wide range of cancers, some of which are easier to treat than others.

- Regional: The cancer has spread outside the liver to nearby structures or lymph nodes. This includes some stage III cancers as well as stage IVA cancers in the American Joint Committee on Cancer system.

- Distant: The cancer has spread to distant parts of the body, such as the lungs or bones. This includes stage IVB cancers.

People now being diagnosed with liver cancer may have a better outlook than these numbers show. Treatments improve over time, and these numbers are based on people who were diagnosed and treated at least five years earlier.

These numbers apply only to the stage of the cancer when it is first diagnosed. They do not apply later on if the cancer grows, spreads, or comes back after treatment.

These numbers don’t take everything into account. Survival rates are grouped based on how far the cancer has spread, but your age, overall health, how well the cancer responds to treatment, and other factors will also affect your outlook.

[Source 1 ]- https://www.cancer.org/cancer/liver-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html[↩]