Contents

- High blood pressure

- What is blood pressure?

- What is normal blood pressure?

- Types of hypertension

- High blood pressure symptoms and signs

- Side effects of high blood pressure

- Causes of high blood pressure

- High blood pressure prevention

- High blood pressure diagnosis

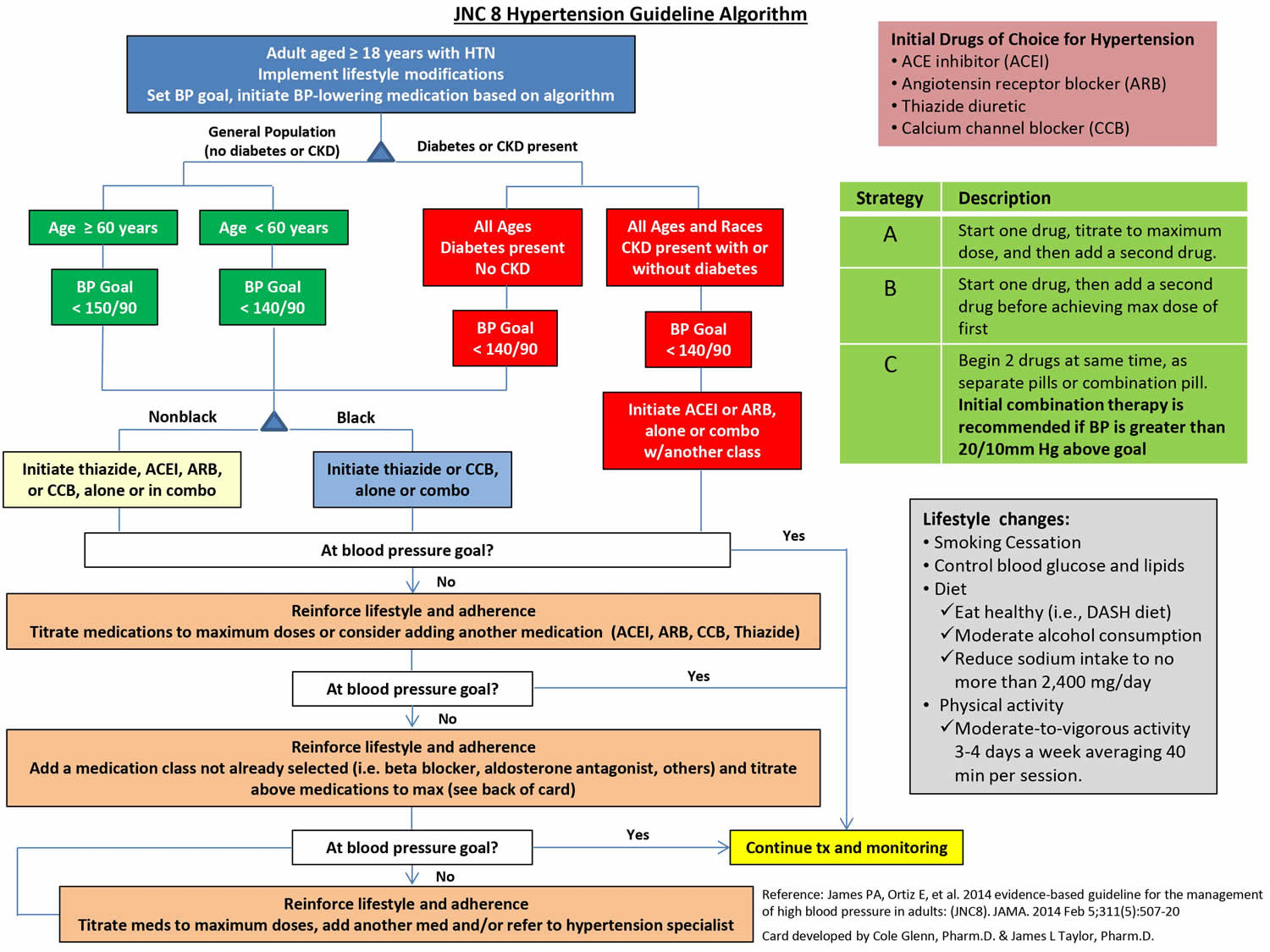

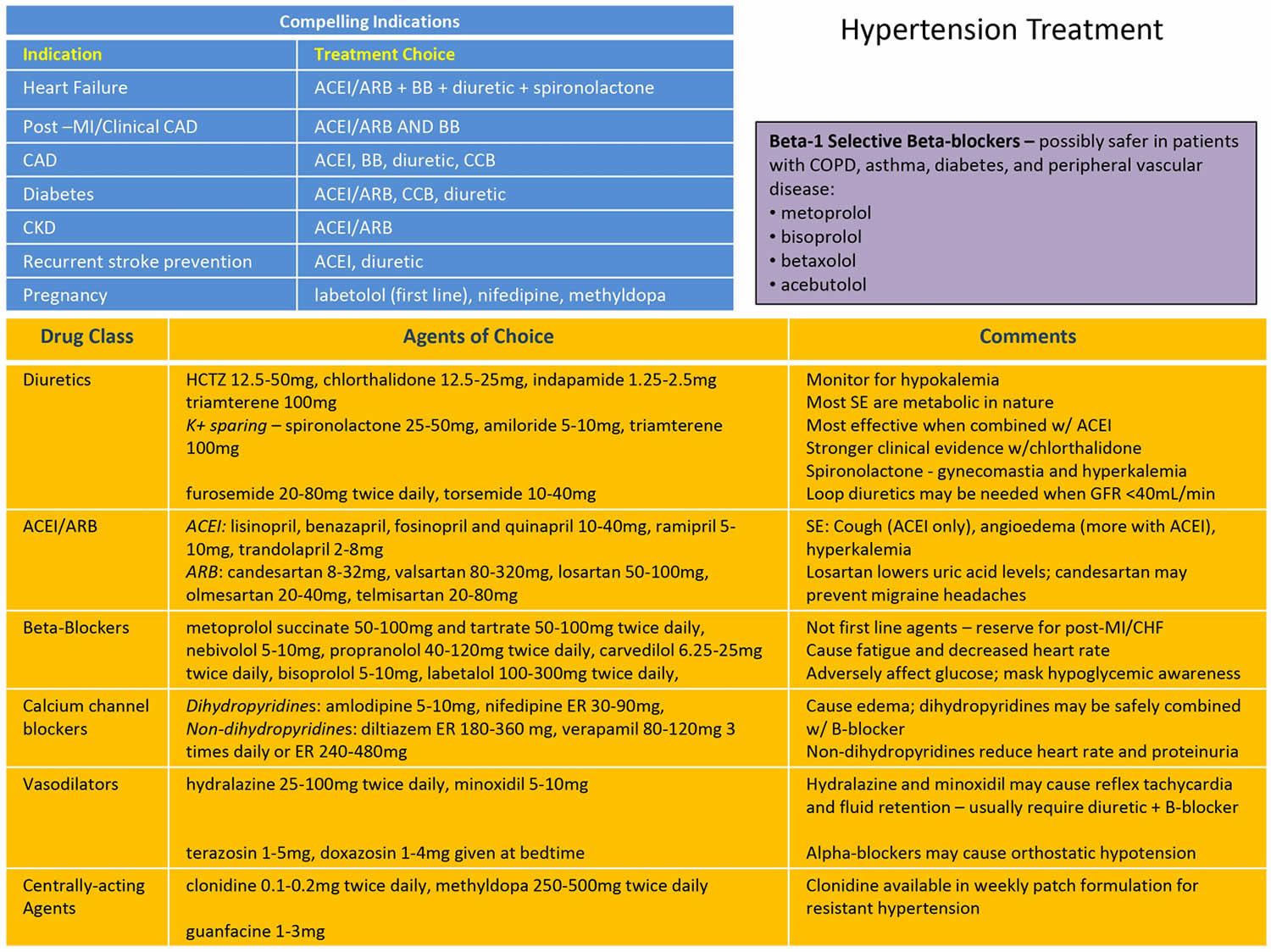

- High blood pressure treatment

- High blood pressure prognosis

High blood pressure

High blood pressure is medically known as hypertension, means your blood pressure is consistently higher-than-normal pressures and that also means your heart has to work harder to pump blood around your body. Your blood pressure is made up of two numbers given in millimeters of mercury (mm Hg): systolic pressure and diastolic pressure. Systolic pressure is the blood pressure when the heart ventricles pump blood out of your heart. Systolic pressure is represented by the top, higher number. Diastolic pressure measures the blood pressure in your arteries between heartbeats when your heart is at rest and is filling with blood and blood is not moving out of your heart. Diastolic pressure is represented by the bottom, lower number. For example, if your blood pressure is “140 over 90” or 140/90 mmHg, it means you have a systolic pressure of 140 mmHg and a diastolic pressure of 90 mmHg. The definition and categories of hypertension have been evolving over the years, high blood pressure is defined as systolic blood pressure 130 mmHg or higher and/or diastolic blood pressure 80 mmHg or higher 1. Your blood pressure is considered high when you have consistent systolic readings of 130 mm Hg or higher or diastolic readings of 80 mm Hg or higher 2. Everyone’s blood pressure will be slightly different. What’s considered low or high for you may be normal for someone else. As a general guide high blood pressure is considered to be 140/90mmHg or higher (or 150/90mmHg or higher if you’re over the age of 80). Readings above 180/120 mm Hg are dangerously high and require immediate medical attention. An ideal blood pressure is usually considered to be between 90/60mmHg and 120/80mmHg. Research have shown that systolic blood pressure greater than 120 mm Hg can be increasingly harmful to health 3, 4. You can have high blood pressure for years without any symptoms. Nearly half of American adults have high blood pressure and are not being treated to control their blood pressure. High blood pressure usually has no symptoms and many people don’t even know they have it 5. So the only way to find out if you have high blood pressure is to get regular blood pressure checks at least once a year from your health care provider. Your doctor will use a gauge, a stethoscope or electronic sensor, and a blood pressure cuff. He or she will take two or more readings at separate appointments before making a diagnosis.

Table 1. Blood pressure classification

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | and/or | Diastolic blood pressure(mmHg) | Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure | American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association 2017 Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <120 | and | <80 | Normal blood pressure | Normal blood pressure |

| 120–129 | and | <80 | Prehypertension | Elevated blood pressure |

| 130–139 | or | 80–89 | Prehypertension | Stage 1 hypertension |

| 140–159 | or | 90–99 | Stage 1 hypertension | Stage 2 hypertension |

| ≥160 | or | ≥100 | Stage 2 hypertension | Stage 2 hypertension |

Footnotes: Blood pressure should be based on an average of ≥2 careful readings on ≥2 occasions. Adults with systolic blood pressure or diastolic blood pressure in 2 categories should be designated to the higher blood pressure category.

[Sources 6, 7 ]The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health has determined 2 levels of high blood pressure for adults (for individuals aged 18 years and above):

- Stage 1 hypertension

- 130 mm Hg to 139 mm Hg systolic pressure

- OR

- 80 mm Hg to 89 mm Hg diastolic pressure

- Stage 2 hypertension

- 140 mm Hg to 159 mm Hg systolic pressure

- OR

- 90 mm Hg to 99 mm Hg diastolic pressure

- Stage 2 hypertension

- Higher than 160 mm Hg systolic pressure

- OR

- Higher than 100 mm Hg diastolic pressure

- Hypertensive crisis

- A blood pressure measurement higher than 180/120 mm Hg is an emergency situation that requires urgent medical care. If you get this result when you take your blood pressure at home, wait five minutes and retest. If your blood pressure is still this high, contact your doctor immediately. If you also have chest pain, vision problems, numbness or weakness, breathing difficulty, or any other signs and symptoms of a stroke (this is when blood flow to your brain stops) or heart attack (also called myocardial infarction), call your local emergency medical number.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute defines “prehypertension” or “elevated blood pressure” as:

- 120 mm Hg to 129 mm Hg systolic pressure

- AND

- Less than 80 mm Hg diastolic pressure

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute guidelines define “normal blood pressure” as follows:

- Less than 120 mm Hg systolic pressure

- AND

- Less than 80 mm Hg diastolic pressure

Low blood pressure is define as:

- Less than 90 mm Hg systolic pressure

- AND

- Less than 60 mm Hg diastolic pressure

The recent European Society of Cardiology and European Society of Hypertension guidelines for individuals aged 16 years and above came out in 2018 and defined hypertension as 8:

- Optimal: systolic blood pressure less than 120 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure less than 80 mmHg

- Normal: systolic blood pressure 120 to 129 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure 80 to 84 mmHg

- High normal: systolic BP 130 to 139 mmHg and/or diastolic BP 85 to 89 mmHg

- Grade 1 hypertension: systolic BP 140 to 159 mmHg and/or diastolic BP 90 to 99 mmHg

- Grade 2 hypertension: systolic BP 160 to 179 mmHg and/or diastolic BP 100 to 109mmHg

- Grade 3 hypertension: systolic BP greater than or equal to 180 mmHg and/or diastolic BP greater than or equal to 110 mmHg

- Isolated systolic hypertension: systolic BP greater than or equal to 140 mmHg and diastolic BP less than 90 mmHg (further classified into Grades as per above ranges of systolic blood pressure)

European Society of Cardiology and European Society of Hypertension recommendations also shed light on home and ambulatory BP measurements and following cut-offs were given 8:

- Daytime (or awake) mean systolic blood pressure greater than or equal to 135mmHg and/or diastolic BP greater than or equal to 85 mmHg

- Night-time (or asleep) mean systolic blood pressure greater than or equal to 120mmHg and/or diastolic BP greater than or equal to 70 mmHg

- 24 hr mean systolic blood pressure greater than or equal to 130mmHg and/or diastolic BP greater than or equal to 80 mmHg

- Home BP mean systolic blood pressure greater than or equal to 135mmHg and/or diastolic BP greater than or equal to 85 mmHg

Isolated systolic hypertension is a condition in which the diastolic pressure is normal (less than 80 mm Hg) but systolic pressure is high (greater than or equal to 130 mm Hg). This is a common type of high blood pressure among people older than 65.

White coat hypertension is an office BP 130/80 mmHg or more but less than 160/100mmHg which comes down to 130/80mmHg or less after at least 3 months of anti-hypertensive therapy 9. Ambulatory or home blood pressure measurement is usually necessary for this diagnosis.

Masked hypertension is an elevated office systolic BP 120 to 129mmHg, and diastolic BP less than 80mmHg but raised BP on ambulatory or home measurements (130/80mmHg or more) 9.

Use these numbers as a guide only. Both numbers in a blood pressure reading are important. But after age 50, the systolic reading is even more important. A single elevated blood pressure measurement is not necessarily an indication of a problem. Because blood pressure normally varies during the day and may increase during a doctor visit (white coat hypertension), your doctor will likely take multiple blood pressure measurements over several days or weeks before making a diagnosis of high blood pressure and starting treatment. If you normally run a lower-than-usual blood pressure, you may be diagnosed with high blood pressure with blood pressure measurements lower than 140/90.

Uncontrolled high blood pressure increases your risk of serious health problems and need urgent treatment in hospital to reduce the risk of a stroke or heart attack. High blood pressure can also cause kidney failure, heart failure, problems with your sight and vascular dementia. Your blood pressure is important because if it is too high, it affects the blood flow to your organs. Over the years, this increases your chances of developing heart disease, stroke, kidney failure, diabetes, eye disease, erectile dysfunction and other conditions. Fortunately, high blood pressure can be easily detected. And once you know you have high blood pressure, you can work with your doctor to control it.

To control or lower high blood pressure, your doctor may recommend that you adopt a heart-healthy lifestyle. This includes choosing heart-healthy foods such as those in the DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) eating plan. You may also need to take medicines. Controlling or lowering blood pressure can help prevent or delay serious health problems such as chronic kidney disease, heart attack, heart failure, stroke, and possibly vascular dementia.

High blood pressure can often be prevented or reduced by eating healthily, maintaining a healthy weight, taking regular exercise, drinking alcohol in moderation and not smoking.

What is blood pressure?

Blood pressure is the pressure of blood in your arteries or the force of blood pushing against your artery walls – the vessels that carry your blood from your heart to your brain and the rest of your body 10. You need a certain amount of pressure to get the blood moving around your body. Your blood pressure is determined both by the amount of blood your heart pumps and the amount of resistance to blood flow in your arteries. The size and elasticity of the artery walls affect blood pressure. The more blood your heart pumps and the narrower your arteries, the higher your blood pressure. High blood pressure, sometimes called hypertension, happens when this force is too high. A blood pressure reading is given in millimeters of mercury (mm Hg). This recording represents how high the mercury column in the blood pressure cuff is raised by the pressure of your blood. Mercury was used in the first accurate pressure gauges and is still used in medicine today as the standard unit of measurement for pressure. Health care workers check blood pressure readings the same way for children, teens, and adults. They use a gauge, stethoscope or electronic sensor, and a blood pressure cuff.

Your blood pressure naturally goes up and down throughout the day and night, and it’s normal for it to go up while you’re moving about. It’s when your overall blood pressure is consistently high, even when you are resting, that you need to do something about it.

Blood pressure is measured in millimeters of mercury (mmHg) and is given as two figures:

- Systolic pressure (the upper number) – the pressure when your heart pushes blood out. The systolic pressure (higher number) is the force at which your heart pumps blood around your body.

- Diastolic pressure (the lower number)– the pressure when your heart rests between beats. The diastolic pressure (lower number) is the resistance to the blood flow in the blood vessels.

For example, if your blood pressure is “140 over 90” or 140/90mmHg, it means you have a systolic pressure of 140mmHg and a diastolic pressure of 90mmHg. Normal blood pressure for adults is defined as a systolic pressure below 120 mmHg and a diastolic pressure below 80 mmHg. It is normal for blood pressures to change when you sleep, wake up, or are excited or nervous. When you are active, it is normal for your blood pressure to increase. However, once the activity stops, your blood pressure returns to your normal baseline range.

Both numbers in a blood pressure reading are important. Typically, more attention is given to systolic blood pressure (the first number) as a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease for people over 50. In most people, systolic blood pressure rises steadily with age due to the increasing stiffness of large arteries, long-term buildup of plaque and an increased incidence of cardiac and vascular disease. However, either an elevated systolic or an elevated diastolic blood pressure reading may be used to make a diagnosis of high blood pressure. According to recent studies, the risk of death from ischemic heart disease and stroke doubles with every 20 mm Hg systolic or 10 mm Hg diastolic increase among people from age 40 to 89. But after age 60, the systolic reading is even more significant. Isolated systolic hypertension is a condition in which the diastolic pressure is normal (less than 90 mm Hg) but systolic pressure is high (greater than 140 mm Hg). This is a common type of high blood pressure among people older than 60.

Your doctor will likely take two to three blood pressure readings each at three or more separate appointments before diagnosing you with high blood pressure. This is because blood pressure normally varies throughout the day, and sometimes specifically during visits to the doctor, a condition called white coat hypertension. Your blood pressure generally should be measured in both arms to determine if there is a difference. It’s important to use an appropriate-sized arm cuff. Your doctor may ask you to record your blood pressure at home and at work to provide additional information.

Blood pressure normally rises with age and body size. Newborn babies often have very low blood pressure numbers that are considered normal for babies, while older teens have numbers similar to adults.

Table 2. Blood Pressure Levels – Adults

| Classification | Systolic and diastolic readings |

|---|---|

| Normal | Systolic: less than 120 mm Hg AND Diastolic: less than 80 mm Hg |

| Elevated | Systolic: 120–129 mm Hg AND Diastolic: less than 80 mm Hg |

| High blood pressure (Stage 1 hypertension) | Systolic: 130–139 mm Hg OR Diastolic: 80–89 mm Hg |

| High blood pressure (Stage 2 hypertension) | Systolic: 140 mm Hg or higher OR Diastolic: 90 mm Hg or higher |

| Hypertensive crisis (you should call your local emergency services number and see a doctor immediately) | Systolic: Higher than 180 mm Hg AND/OR Diastolic: Higher than 120 mm Hg |

Footnote: Healthy and unhealthy blood pressure ranges. A blood pressure reading between 120/80mmHg and 140/90mmHg could mean you’re at risk of developing high blood pressure if you don’t take steps to keep your blood pressure under control. A hypertensive crisis (high blood pressure crisis) is when blood pressure rises quickly and severely with readings of 180/120 or greater. If your blood pressure reading is 180/120 or greater and you are experiencing any other associated symptoms of target organ damage such as chest pain, shortness of breath, back pain, numbness/weakness, change in vision, or difficulty speaking then this would be considered a hypertensive emergency. Do not wait to see if your pressure comes down on its own, call your local emergency number immediately.

The consequences of uncontrolled blood pressure in this range can be severe and include:

- Stroke

- Loss of consciousness

- Memory loss

- Heart attack

- Damage to the eyes and kidneys

- Loss of kidney function

- Aortic dissection

- Angina (unstable chest pain)

- Pulmonary edema (fluid backup in the lungs)

- Eclampsia

An elevated reading may or may not be accompanied by one or more of the following symptoms:

- Severe headache

- Shortness of breath

- Nosebleeds

- Severe anxiety

Table 3. Blood Pressure Categories and Stages – Children

| For children aged 1–13 years | For children aged ≥ 13 years |

|---|---|

| Normal BP: < 90th percentile | Normal BP: < 120/< 80 mm Hg |

| Elevated blood pressure: ≥ 90th percentile to < 95th percentile or 120/80 mm Hg to < 95th percentile (whichever is lower) | Elevated blood pressure: 120/< 80 to 129/< 80 mm Hg |

| Stage 1 hypertension: ≥ 95th percentile to < 95th percentile + 12 mm Hg, or 130/80 to 139/89 mm Hg (whichever is lower) | Stage 1 hypertension: 130/80 to 139/89 mm Hg |

| Stage 2 hypertension: ≥ 95th percentile + 12 mm Hg, or ≥ 140/90 mm Hg (whichever is lower) | Stage 2 hypertension: ≥ 140/90 mm Hg |

- Most of the time there are no obvious symptoms for high blood pressure.

- The only way to find out if your blood pressure is high is to have your blood pressure checked.

- Certain physical traits and lifestyle choices can put you at a greater risk for developing high blood pressure.

- When left untreated, the damage that high blood pressure does to your circulatory system is a significant contributing factor to heart attack, stroke and other health threats.

Ask your doctor for a blood pressure reading at least every two years starting at age 18. If you’re age 40 or older, or you’re age 18-39 with a high risk of high blood pressure, ask your doctor for a blood pressure reading every year.

If you don’t regularly see your doctor, you may be able to get a free blood pressure screening at a health resource fair or other locations in your community. You can also find machines in some stores that will measure your blood pressure for free.

Public blood pressure machines, such as those found in pharmacies, may provide helpful information about your blood pressure, but they may have some limitations. The accuracy of these machines depends on several factors, such as a correct cuff size and proper use of the machines.

What is normal blood pressure?

For most adults, a normal blood pressure is less than 120/80 mmHg 2. An ideal blood pressure is usually considered to be between 90/60mmHg and 120/80mmHg. See your healthcare provider if your blood pressure readings are consistently higher than 120/80 mmHg. Blood pressure readings between 120/80mmHg and 140/90mmHg could mean you’re at risk of developing high blood pressure if you do not take steps to keep your blood pressure under control. For children younger than 13, blood pressure readings are compared with readings common for children of the same, age, sex, and height. In children younger than 13 years, elevated blood pressure is defined as blood pressure in the 90th percentile or higher for age, height, and sex, and hypertension is defined as blood pressure in the 95th percentile or higher 14. In adolescents 13 years and older, elevated blood pressure is defined as blood pressure of 120 to 129 mm Hg systolic and less than 80 mm Hg diastolic, and hypertension is defined as blood pressure of 130/80 mm Hg or higher.

Types of hypertension

There are two types of high blood pressure (hypertension).

Primary (essential) hypertension

For most adults, there’s no identifiable cause (idiopathic) of high blood pressure. This type of high blood pressure, called primary hypertension or essential hypertension, tends to develop gradually over many years. It has long been suggested that an increase in salt intake increases the risk of developing hypertension 15. One of the described factors for the development of essential hypertension is the patient genetic ability to salt response 16. About 50 to 60% of the patients are salt sensitive and therefore tend to develop hypertension 17.

Secondary hypertension

Some people have high blood pressure caused by an underlying condition. This type of high blood pressure, called secondary hypertension, tends to appear suddenly and cause higher blood pressure than does primary hypertension. Various conditions and medications can lead to secondary hypertension, including:

- Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)

- Kidney disease

- Adrenal gland tumors

- Thyroid problems

- Certain defects you’re born with (congenital) in blood vessels

- Certain medications, such as birth control pills, cold remedies, decongestants, over-the-counter pain relievers and some prescription drugs

- Illegal drugs, such as cocaine and amphetamines

Isolated systolic hypertension

Isolated systolic hypertension is the predominant form of hypertension in the elderly population 18. Based on data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999-2010, approximately 30% of persons aged 60 years and above have untreated isolated systolic hypertension, as compared with 6% in adults aged 40 to 50 years and 1.8% in young adults aged 18 to 39 years 19. As per the Framingham Heart Study, a person aged 65 years with normal blood pressure has a 90% lifetime risk of developing hypertension. Among the elderly group, women and non-Hispanic Blacks have a higher prevalence of hypertensive disorders.

Isolated systolic hypertension is traditionally defined as systolic blood pressure above 140 mmHg with diastolic blood pressure of less than 90 mmHg 20. It is estimated that 15% of people aged 60 years and above have isolated systolic hypertension. Per the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Blood Pressure guidelines, however, a systolic blood pressure of 130 mmHg is now considered hypertensive at all ages 7. The new definition of hypertension will lead to an increased number of elderly being diagnosed with high blood pressure. Isolated systolic hypertension remains an important public health concern as chronically untreated high systolic blood pressure patients carry significant mortality and morbidity.

Most patients with isolated systolic hypertension have primary hypertension, which is also known as essential hypertension. Rarely, isolated systolic hypertension is attributed to other causes of secondary hypertension such as hypothyroidism/hyperthyroidism, chronic kidney disease, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes mellitus, aortic insufficiency, arteriovenous fistula, anemia, Paget disease, and atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis 21.

Isolated systolic hypertension, in most cases, develops as a result of the reduced elasticity of the arterial system 20. This is commonly seen among the elderly as there is increased deposition of calcium and collagen to the arterial wall 22. Hence, this may result in reduced compliance of the arterial vessels, decreased lumen-to-wall ratio, and increased thickening and fibrotic remodeling of the vascular intima and media. As a result, these stiffened conduit arteries lead to an increase in pulse pressure and pulse wave velocity, causing an elevation in systolic blood pressure and a further decline in diastolic blood pressure. Similarly, chronic diseases such as the above causes of secondary hypertension may contribute to the same pathological process by accelerating the deposition of calcium and collagen to the arterial system and the fibrotic remodeling of the vascular walls 23.

Malignant hypertension

Malignant hypertension also known as hypertensive crisis, is a term that has been used to describe patients with elevated blood pressure and multiple complications (end organ damage) with a poor prognosis. Today, the term malignant hypertension or hypertensive crisis is used to describe patients who present with severe BP elevations as follow 24:

- Systolic blood pressure greater than 180 mm Hg

- Diastolic blood pressure greater than 120 mm Hg

To make a diagnosis of malignant hypertension, papilledema has to be present 24. The diagnosis can be further classified as a hypertensive emergency when severe elevation in BP is associated with end-organ damage or hypertensive urgency when severe hypertension occurs without it. Prompt treatment of BP can prevent a hypertensive emergency and, consequently, serious life-threatening complications 25.

There are multiple causes of malignant hypertension (hypertensive crisis), including the following 24:

- Medication noncompliance

- Renovascular diseases, such as renal artery stenosis, polyarteritis nodosa, and Takayasu arteritis

- Renal parenchymal disease including glomerulonephritis, tubulointerstitial nephritis, systemic sclerosis, hemolytic-uremic syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus

- Endocrine dysfunction, such as pheochromocytoma, Cushing disease, primary hyperaldosteronism, renin-secreting tumor

- Coarctation of aorta; drugs or other exposures, including cocaine, phencyclidine, sympathomimetics, erythropoietin, cyclosporine

- Antihypertensive medication withdrawal

- Amphetamines

- Central nervous system disorders, such as head injury, cerebral infarction, and cerebral hemorrhage

The prognosis of patients with malignant hypertension is guarded. Five-year survivals of 75% to 84% have been reported with treatment; without treatment, the life expectancy is less than 24 months. Most deaths are a result of heart failure, stroke, or renal failure.

Multiple complications can arise from hypertensive crisis when target organs are affected, including encephalopathy, intracerebral hemorrhage, acute myocardial infarction, acute heart failure, pulmonary edema, unstable angina, dissecting aortic aneurysm, acute kidney injury, and vision loss. Fortunately, most patients with malignant hypertension have no acute end-organ damage (hypertensive urgency). Nevertheless, some patients have signs and symptoms of acute, ongoing injury, which is recognized as hypertensive emergency.

In malignant hypertension (hypertensive emergency), the key is to lower the blood pressure within a few hours. However, it is not recommended to decrease the blood pressure too fast or too much, as ischemic damage can occur in vascular territories that have become habituated with the elevated level of blood pressure 24. For most hypertensive emergencies, mean arterial pressure (MAP) should be reduced by approximately 10 to 20% within the first hour and by another 5% to 15% over the next 24 hours 24. This often results in a target blood pressure of less than 180/120 mm Hg for the first hour and less than 160/110 mm Hg for the next 24 hours, but rarely less than 130/80 mm Hg during that time frame.

Common intravenous (IV) medications and doses used to treat malignant hypertension (hypertensive emergencies) include:

- Nicardipine, initial infusion rate 5 mg per hour, increasing by 2.5 mg per hour every 5 minutes to a maximum of 15 mg per hour

- Sodium nitroprusside, 0.3 to 0.5 mcg/kg/minute, increases by 0.5 mcg/kg per minute every few minutes as needed to a maximum dose of 10 mcg/kg per minute.

- Labetalol 10 to 20 mg IV followed by bolus doses of 20 to 80 mg at 10-minute intervals until a target blood pressure is reached to a maximum 300-mg cumulative dose

- Esmolol, initial loading dose 500 mcg/kg/minute over 1 minute, then 50 to 100 mcg/kg/minute to a maximum dose of 300 mcg/kg per minute.

If there is any possibility of over or underestimating BP using frequent noninvasive cuff measurements or if the end-organ damage is life-threatening, consider arterial catheterization for precise, second-to-second measurements allowing for more careful medication titration.

The major exceptions to gradual BP lowering over the first day are:

- Acute phase of an ischemic stroke: The BP is usually not treated unless it is greater than 185/110 mmHg in patients whose reperfusion therapy could be an option or greater than 220/120 mm Hg in patients who might not qualify for it. Consider labetalol or nicardipine infusion.

- Acute aortic dissection: The SBP should be lowered to 120 mm Hg within 20 minutes, and a target heart rate around 60 beats per minute to reduce aortic shearing forces. Treatment usually requires a beta-blocker and a vasodilator. Options include esmolol, nicardipine, or nitroprusside.

- An intracerebral hemorrhage: The goals of therapy are different and depend on the location and surgical approach.

- Acute myocardial ischemia: Nitroglycerin is the drug of choice; do not use if the patient has taken phosphodiesterase inhibitors, including sildenafil or tadalafil, within the past 48 hours.

After a suitable period, often 8 to 24 hours of BP control at a target, oral medications are usually given, and the initial intravenous therapy is tapered and discontinued.

Renovascular hypertension

Renovascular hypertension is one of the most common causes of secondary hypertension and often leads to resistant hypertension. Renovascular hypertension is defined as systemic hypertension that manifests secondary to the compromised blood supply to the kidneys, usually due to an occlusive lesion in the main renal artery 26. It is important to realize that any condition that compromises blood flow to the kidneys can contribute to renovascular hypertension 27. The underlying mechanism in renovascular hypertension involves decreased perfusion to the kidney and activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone (RAAS) pathway. Renin secretion by the kidneys is stimulated by three main pathways, 1) renal baroreceptors that sense decreased perfusion to the kidney, 2) low sodium chloride levels detected by the macula densa and 3) beta-adrenergic stimulation. Prolonged kidney ischemia also increases the number of renin expressing cells in the kidney in a process called ‘juxtaglomerular (JG) recruitment’ 28. When renin is secreted into the blood, it acts on angiotensinogen (produced by the liver). Renin cleaves angiotensinogen to angiotensin 1, which is then converted to angiotensin 2 by angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) that is primarily found in the vascular endothelium of lungs and kidney. Angiotensin 2 raises blood pressure by multiple mechanisms, which include:

- Vasoconstriction, mostly in the heart, kidney, and vascular smooth muscle 29

- Sympathetic nervous stimulation causing a presynaptic release of norepinephrine

- Stimulates secretion of aldosterone by the adrenal cortex, which in turn causes sodium and water retention, thereby raising blood pressure.

- It also causes the increased synthesis of collagen type I and III in fibroblasts, leading to thickening of the vascular wall and myocardium, and fibrosis

- It has been shown to have a growth effect on renal cells, which has been implicated in the development of glomerulosclerosis and tubulointerstitial fibrosis

The most common causes of renovascular hypertension include 26:

- Renal artery stenosis (RAS), mostly secondary to atherosclerosis

- Fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD)

- Arteritides such as Takayasu’s arteritis, antiphospholipid antibody (APLA), or mid aortic syndrome 30

- Extrinsic compression of a renal artery

- Renal artery dissection or infarction

- Radiation fibrosis

- Obstruction from aortic endovascular grafts

The dominant cause (at least 85%) of renovascular hypertension in western countries is atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis (ARAS) and is mostly seen in older adults (>65 years) 27. This often develops as part of systemic atherosclerotic disease affecting multiple vascular beds, including coronary, cerebral and peripheral vessels. Community based studies suggest that up to 6.8% of individuals older than 65 have atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis (ARAS) more than 60% occlusion 31. Renal artery stenosis secondary to atherosclerosis has a higher prevalence in patients with known atherosclerotic disease (such as those with coronary artery disease, peripheral artery disease, or carotid artery stenosis) and autopsy studies have revealed that “greater than 25% of all patients who die of cardiovascular disease have some degree of renal artery stenosis” 32. Screening studies indicate rising prevalence of detectable atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis (ARAS) in hypertensive subjects from 3% (ages 50-59) to 25% (above age 70) with older ages 33. Clinically significant atherosclerotic renovascular disease often is manifest by worsening or accelerating blood pressure elevations in older individuals with pre-existing hypertension.

Fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD) is usually seen in young women and accounts for around 10% of renovascular hypertension and 5.8% of secondary hypertension 34. Fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD) can affect any arterial bed but most commonly affects the distal two-thirds of the renal artery 35.

Salient points in the history that suggest the presence of renovascular hypertension include:

- Resistant hypertension: Uncontrolled blood pressure necessitating the use of 2 or 3 antihypertensive agents of different classes, one of which is a diuretic

- Trial of multiple medications to control blood pressure

- History of multiple hospital admissions for hypertensive crisis

- Elevation in creatinine of more than 30% after starting an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACE-I)

- Patients with renal artery stenosis secondary to atherosclerosis are usually older and might have the presence of other atherosclerotic diseases such as carotid artery stenosis, peripheral artery stenosis, or coronary artery disease

- A premenopausal female (15-50 years) with hypertension is most likely to have fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD) 30

- Long term history of smoking

- Patients with systemic vasculitis can develop vasculitis of renal arteries and present with renovascular hypertension

- Recurrent episodes of flash pulmonary edema and/or unexplained congestive heart failure

- Unexplained azotemia

- Elevation in serum creatinine upon starting angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor, which occurs due to interference with autoregulation and post glomerular arterial tone

- Unexplained hypokalemia and metabolic alkalosis

- Unilateral small or atrophic kidney

Physical examination may reveal an abdominal bruit, indicating the presence of renal artery stenosis.

Patients with renovascular hypertension often undergo an extensive evaluation to find a cause for uncontrolled hypertension.

Laboratory Tests include:

- Urine analysis: To check for proteinuria, hematuria, and casts. The presence of proteinuria (protein in urine) indicates the presence of renal parenchymal disorder, whereas the presence of hematuria (blood in urine) or red blood cell (RBC) casts indicates the presence of glomerulonephritis.

- Blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine: To assess baseline kidney function.

- Basal metabolic profile: To assess for electrolyte disturbances and acid-base balance.

- Complement levels and autoimmune profile: In suspected cases of autoimmune diseases affecting the renal vasculature.

- Plasma free metanephrines or 24-hour urinary fractionated metanephrines and normetanephrine to rule out pheochromocytoma

- Plasma renin-aldosterone ratio to rule out hyperaldosteronism

- 24 hour urinary free cortisol or low dose dexamethasone suppression test to rule out Cushing’s syndrome

Imaging studies

There are multiple imaging modalities available to evaluate renovascular hypertension. Since the most common cause of renovascular hypertension is renal artery stenosis, renal arteriography remains the gold standard diagnostic test 35. However, catheter angiography is invasive, costly, time-consuming, and can lead to complications such as renal artery dissection or cholesterol embolization. Other imaging tests that can be done to evaluate the renal vessels include duplex ultrasonography, computed tomography with angiography (CTA), and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA). The type of imaging test used often depends on the suspicion for high-grade lesions, and the need for intervention 30.

Duplex ultrasonography is the initial imaging test of choice to evaluate the renal arteries. It is relatively inexpensive, non-invasive, and does not involve administration of contrast or exposure to radiation. A duplex scan has been shown to have an excellent correlation with contrast-enhanced angiography 36. Though there are several criteria to assess the presence of renal artery stenosis, the most important sign is peak systolic velocity (PSV). A peak systolic velocity (PSV) higher than 180 cm/s suggests the presence of stenosis of greater than 60% 37.

Duplex ultrasonography can also measure the resistive index (RI), which is calculated as (PSV-End diastolic velocity)/PSV. A value of more than 0.7 indicates the presence of pathological resistance to flow, and studies have shown that a value >0.8 predicts poor response to revascularization treatments 37. The most significant setbacks for duplex ultrasonography are its reduced sensitivity in obese patients, hindrance by overlying bowel gas, and operator dependence.

CT angiography (CTA) involves the administration of intravenous contrast and acquiring detailed images of blood vessels or tissues by moving the beam in a helical manner across the area being studied. In a study by Wittenberg et al 38, the sensitivity and specificity for hemodynamically significant renal artery stenosis (>50%) by CTA was found to be 96% and 99%. Computed tomography with angiography (CTA) also has a comparable negative predictive value to magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) in ruling out renal artery stenosis 39.

It can also diagnose extrinsic compression of renal arteries, fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD), arterial dissection, and help in evaluating surrounding structures. However, CT angiography (CTA) can only provide an anatomical assessment of the lesion and is not able to evaluate the degree of obstruction to renal blood flow. Exposure to radiation, allergy to contrast, and acute kidney injury are other downfalls of CT angiography (CTA).

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) uses a powerful magnetic field, pulses of radio waves, and intravenous gadolinium to evaluate the renal blood vessels and surrounding structures. Several studies have shown the sensitivity and specificity of magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) to be around 97% and 92% in diagnosing renal artery stenosis 39. MRA does not involve radiation, and gadolinium contrast is less likely to cause an allergic reaction as compared to the iodine contrast used in CTA. However, MRA has been shown to overestimate the grade of stenosis and is often affected by motion artifacts or opacification of renal veins, leading to difficulty visualizing the renal arteries 39. Also, gadolinium has been shown to induce a rare, progressively fatal disease called nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF). NSF can affect the skin, joints, and multiple organs leading to progressive, irreversible fibrosis and eventual death. This occurs due to a transmetalation reaction that displaces gadolinium ion from its chelate, resulting in the deposition of gadolinium in the skin and soft tissues. The 1-year incidence of NSF has been reported to be around 4.6% and almost all cases occurred in patients with a glomerular filtration rate < 30 mL/min/1.73 m² 40.

In comparative studies, the positive predictive value of MRA was found to be higher than CTA due to increased false-positive rates with CTA. Negative predictive values are high for both CTA and MRA (>98% for both) 39. Both modalities can exclude significant renal artery lesions with a high degree of certainty. Both MRA and CTA have also shown to be effective for the diagnosis of FMD, with the sensitivity of CTA being the best (84.2%) when compared to angiography 41.

Nuclear medicine ACE-inhibitor (ACE-I) renography is another non-invasive, relatively safe imaging method that uses radioactive material, a special camera, and a computer to evaluate for renovascular hypertension. It involves the administration of an ACE-inhibitor (ACE-I) to determine if the cause of hypertension is due to the narrowing of the renal arteries. The sensitivity and specificity of this test have shown to be variable, with values between 74% – 94% for sensitivity and 59% – 95% for specificity 42. It is a time-consuming procedure, and there is a risk of radiation exposure and irritation or pain from the injection of the radiotracer. The sensitivity of ultrasound has shown to be higher than captopril renography which makes it a better choice for an initial diagnostic test 43.

Catheter angiography is the gold standard test to evaluate for renovascular hypertension and provides the best temporal and spatial resolution. Catheter angiography has the added advantage of measuring translesional pressure gradients to assess the hemodynamic significance of anatomically severe lesions 44. Catheter angiography is most useful in:

- Patients with a disparity between imaging modalities

- Patients with a high index of suspicion and negative imaging findings

- Patients anticipated of needing an intervention

Catheter angiography can also evaluate anatomical abnormalities of the kidney, renal arteries, aorta, and can be followed by endovascular intervention for the treatment of significant lesions. Also, the surrounding tissues and bones can be removed or subtracted from the final image revealing only the arterial framework. This method is known as digital subtraction angiography (DSA). However, the radiation doses are higher than CTA, and because it is an invasive procedure, there are risks of complications such as arterial dissection, tear, rupture, or thromboembolic phenomenon 44.

The management of renovascular hypertension aims to treat the underlying cause. Several options are available, which include pharmacological and invasive therapy. Renovascular hypertension due to atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis should be primarily managed medically as multiple studies have failed to show renal or cardiovascular benefits with invasive management.

Pharmacological therapy entails the use of antihypertensive medications to control blood pressure. The American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association advocates pharmacological therapy as the first-line treatment for renal artery stenosis 45. Since renin-angiotensin-aldosterone (RAAS) is the most prominent pathway contributing to hypertension in these disorders, ACE-inhibitors (ACE-Is) and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) form the cornerstone of managing renovascular hypertension. Often more than one medication will be needed to control the blood pressure. Calcium channel blockers, thiazides, beta-blockers, and hydralazine have been shown to be effective to control blood pressure in patients with renal artery stenosis 46. Direct renin inhibitors such as aliskiren have been studied as monotherapy or in combination with ACE-inhibitors (ACE-Is) and angiotensin 2 receptor blockers (ARBs) to treat hypertension. Though it has been shown to be effective for the treatment of hypertension there is not enough data to prove its efficacy in treating renovascular hypertension 47.

ACE-inhibitors (ACE-Is) and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) inhibit the action of angiotensin II, thereby causing vasodilation and promote sodium and water excretion. However, these medications are contraindicated in patients with a single functioning kidney or bilateral lesions as they can cause efferent arteriolar vasodilatation leading to interruption in autoregulation and thereby decreasing glomerular filtration. While these medications are effective in controlling blood pressure, they can also lead to worsening renal function.

Percutaneous angioplasty is the treatment of choice for renovascular hypertension due to fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD) and for patients with atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis that is not controlled with medications 48. The American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association guidelines recommend revascularization for renal artery disease in the following scenarios 46:

- Patients with hemodynamically significant renal artery stenosis and recurrent, unexplained congestive heart failure or sudden, unexplained pulmonary edema

- Hemodynamically significant renal artery stenosis and accelerated hypertension, resistant hypertension, malignant hypertension or hypertension with an unexplained unilateral small kidney, and hypertension with intolerance to medication

- Patients with bilateral renal artery stenosis and progressive chronic kidney disease or a renal artery stenosis to a solitary functioning kidney

- Patients with hemodynamically significant renal artery stenosis and unstable angina

- Asymptomatic bilateral or solitary viable kidney with hemodynamically significant renal artery stenosis

- Patients with renal artery stenosis and chronic renal insufficiency with unilateral renal artery stenosis

- In addition to angioplasty, renal stent placement is indicated for patients with ostial atherosclerotic lesions

Patients with fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD) and renovascular hypertension are also treated with percutaneous intervention with or without a stent 48. Multiple studies have shown a decrease in baseline blood pressure after intervention for fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD) 49. However, there remains an ongoing debate about the benefit of revascularization when compared to medical management in patients with atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis (ARAS). Several studies have failed to show a significant decrease in blood pressure or the number of antihypertensive agents between angioplasty and medical treatment groups. A meta-analysis of 7 trials by Zhu et al. 50 revealed that medical management is as effective as percutaneous revascularization in the treatment of renal artery stenosis. Three recent trials: the Angioplasty and Stenting for Renal Artery Lesions (ASTRAL) 51, Cardiovascular Outcomes in Renal Atherosclerotic Lesions (CORAL) 52, and STAR 53 found no difference between stenting and medical therapy in patients with atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis. Thus it can be established that revascularization does not reverse renal damage or decrease blood pressure in patients with atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis.

In the case of recurrent renal artery stenosis or blood pressure not controlled with medication and or/angioplasty, renal bypass surgery may be an option. In this procedure, the surgeon uses a vein or synthetic tube to connect the kidney to the aorta, to create an alternate route for blood to flow around the blocked artery into the kidney. This is a complex procedure and rarely used. The American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association guidelines recommend surgery for renal artery stenosis in 46:

- Patients with renal artery stenosis secondary to fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD), especially those with complex disease and/or those having microaneurysms

- Patients with atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis involving multiple vessels or involvement of early primary branch of the main renal artery

- Patients with atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis who require pararenal aortic reconstructions (such as with aortic aneurysms or severe aortoiliac obstruction)

Several studies have also evaluated the role of unilateral nephrectomy in patients with renovascular hypertension and have shown improvement in blood pressure control, renal function, and a decrease in the use of anti-hypertensives 54. However, this is an invasive procedure with inherent risks and the long-term consequences of such a procedure are unclear.

Untreated renovascular hypertension can also lead to end-stage renal failure with a median survival time of 25 months and a 4-year mortality rate of 35% 26.

Hypertension in pregnancy

Some women have high blood pressure before they get pregnant. Others have high blood pressure for the first time during pregnancy. About 8 in 100 women (8 percent) have some kind of high blood pressure during pregnancy. If you have high blood pressure, talk to your health care provider. Managing your blood pressure can help you have a healthy pregnancy and a healthy baby.

Two kinds of high blood pressure that can happen during pregnancy:

- Chronic hypertension. Chronic hypertension is high blood pressure that you have before you get pregnant or that develops before 20 weeks of pregnancy. Chronic hypertension doesn’t go away once you give birth. Chronic hypertension is diagnosed per American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists guidelines as an in-office measurement with systolic blood pressure greater than 140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure greater than 90mmHg confirmed with either ambulatory blood pressure monitoring, home blood pressure monitoring, or blood pressure evaluation with serial office visits, with elevated pressures at least 4 hours apart prior to 20 weeks gestation 55, 56, 57. About 1 in 4 women with chronic hypertension (25 percent) has preeclampsia during pregnancy. If you’re at high risk for preeclampsia, your health care provider may treat you with low-dose aspirin to prevent it. Your health care provider will check your blood pressure and urine at each prenatal care visit. You may need to check your blood pressure at home, too. Your health care provider may also use ultrasound and fetal heart rate testing to check your baby’s growth and health. Your health care provider also checks for signs of preeclampsia. If you were taking medicine for chronic hypertension before pregnancy, your health care provider makes sure it’s safe to take during pregnancy. If it’s not, he/she switches you to a safer medicine. Some blood pressure medicines, called ACE inhibitors (ACE-I) and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), can harm your baby during pregnancy. During the first half of pregnancy, blood pressure often falls. If you have mild hypertension and took medicine for it before pregnancy, your health care provider may lower the dose of medicine you take. Or you may be able to stop taking medicine during pregnancy. Don’t stop taking any medicine before you talk to your health care provider. Even if you didn’t take blood pressure medicine in the past, you may need to start taking it during pregnancy.

- Gestational hypertension. Gestational hypertension is high blood pressure that only pregnant women can get. Gestational hypertension is defined per American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists guidelines as blood pressure greater than or equal to 140 mmHg systolic or 90mmHg diastolic on two separate occasions at least four hours apart after 20 weeks of pregnancy when previous blood pressure was normal with no excess protein in their urine or other signs of organ damage. Alternatively, a patient with systolic blood pressure greater than 160 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure greater than 110 mmHg can be confirmed to have gestational hypertension if they have a similar pressure after a short interval. This is in order to ensure timely antihypertensive treatment. Gestational hypertension starts after 20 weeks of pregnancy and usually goes away after you give birth. It usually causes a small rise in blood pressure, but some women develop severe hypertension and may be at risk for more serious complications later in pregnancy, like preeclampsia.

- Chronic hypertension with superimposed preeclampsia. This condition occurs in women who have been diagnosed with chronic high blood pressure before pregnancy, but then develop worsening high blood pressure and protein in the urine or other health complications during pregnancy.

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy includes chronic hypertension, with or without superimposed pre-eclampsia/eclampsia, gestational hypertension, HELLP syndrome, preeclampsia with or without severe features or eclampsia present a significant risk of morbidity to both mother and fetus. HELLP stands for hemolysis (H), elevated liver enzymes (EL), low platelet count (LP) syndrome.

High blood pressure in pregnancy can cause problems for you and your baby during pregnancy, including 58:

- Problems for moms include:

- Preeclampsia. Preeclampsia is a complication of pregnancy in which affected women develop high blood pressure (hypertension); they can also have abnormally high levels of protein in their urine (proteinuria) and signs of damage to another organ system, most often the liver and kidneys. Preeclampsia usually begins after 20 weeks of pregnancy in women whose blood pressure had been normal or after giving birth (called postpartum preeclampsia). Signs and symptoms of preeclampsia include having protein in the urine, changes in vision and severe headaches. Preeclampsia can be a serious medical condition. Even if you have mild preeclampsia, you need treatment to make sure it doesn’t get worse. Without treatment, preeclampsia can cause serious health problems, including kidney, liver and brain damage. In rare cases, it can lead to life-threatening conditions called eclampsia and HELLP syndrome. Eclampsia causes seizures and can lead to coma. HELLP syndrome stands for hemolysis (H) which is the destruction of red blood cells, elevated liver enzymes (EL), low platelet count (LP) syndrome. HELLP syndrome is a more severe form of preeclampsia, and can rapidly become life-threatening for both you and your baby. Left untreated, preeclampsia can lead to serious — even fatal — complications for both you and your baby. If you have preeclampsia, the most effective treatment is delivery of your baby. Even after delivering the baby, it can still take a while for you to get better.

- Gestational diabetes. This is a kind of diabetes that only pregnant women get. It’s a condition in which your body has too much sugar (also called glucose). Most women get a test for gestational diabetes at 24 to 28 weeks of pregnancy.

- Heart attack (also called myocardial infarction).

- Kidney failure. This is a serious condition that happens when the kidneys don’t work well and allow waste to build up in the body.

- Placental abruption. This is a serious condition in which the placenta separates from the wall of the uterus before birth. If this happens, your baby may not get enough oxygen and nutrients in the womb. You also may have serious bleeding from the vagina. The placenta grows in the uterus and supplies the baby with food and oxygen through the umbilical cord.

- Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH). This is when a woman has heavy bleeding after giving birth. It’s a serious but rare condition. It usually happens 1 day after giving birth, but it can happen up to 12 weeks after having a baby.

- Pulmonary edema. This is when fluid fills the lungs and leads to shortness of breath.

- Stroke. This is when blood flow to your brain stops. Stroke can happen if a blood clot blocks a vessel that brings blood to the brain or when a blood vessel in the brain bursts open.

- Pregnancy related death. This is when a woman dies during pregnancy or within 1 year after the end of her pregnancy from health problems related to pregnancy.

If you have high blood pressure during pregnancy, you’re also more likely have a cesarean birth (also called c-section). This is surgery in which your baby is born through a cut that your doctor makes in your belly and uterus.

- Problems for babies include:

- Premature birth. This is birth that happens too early, before 37 weeks of pregnancy. Even with treatment, a pregnant woman with severe high blood pressure or preeclampsia may need to give birth early to avoid serious health problems for her and her baby.

- Fetal growth restriction. High blood pressure can narrow blood vessels in the umbilical cord. This is the cord that connects the baby to the placenta. It carries food and oxygen from the placenta to the baby. If you have high blood pressure, your baby may not get enough oxygen and nutrients, causing him to grow slowly.

- Low birthweight. This is when a baby is born weighing less than 5 pounds, 8 ounces.

- Fetal death. When a baby dies spontaneously in the womb at any time during pregnancy.

- Neonatal death. This is when a baby dies in the first 28 days of life.

To manage high blood pressure during pregnancy:

- Go to all your prenatal care checkups, even if you’re feeling fine.

- If you need medicine to control your blood pressure, take it every day. Your doctor can help you choose one that’s safe for you and your baby.

- If you have severe preeclampsia or HELLP syndrome, corticosteroid medications can temporarily improve liver and platelet function to help prolong your pregnancy. Corticosteroids can also help your baby’s lungs become more mature in as little as 48 hours — an important step in preparing a premature baby for life outside the womb.

- If your preeclampsia is severe, your doctor may prescribe an anticonvulsant medication, such as magnesium sulfate, to prevent a first seizure.

- Do not take any extra vitamins, calcium, aspirin, or other medicines without talking with your doctor first.

- Check your blood pressure at home. Ask your doctor what to do if your blood pressure is high.

- Eat healthy foods. Don’t eat foods that are high in salt, like soup and canned foods. They can raise your blood pressure.

- Stay active. Being active for 30 minutes each day can help you manage your weight, reduce stress and prevent problems like preeclampsia.

- Don’t smoke, drink alcohol or use street drugs or abuse prescription drugs.

- Contact your doctor immediately or go to an emergency room if you have severe headaches, blurred vision or other visual disturbance, severe pain in your abdomen, or severe shortness of breath. Because headaches, nausea, and aches and pains are common pregnancy complaints, it’s difficult to know when new symptoms are simply part of being pregnant and when they may indicate a serious problem — especially if it’s your first pregnancy. If you’re concerned about your symptoms, contact your doctor.

Pulmonary hypertension

Pulmonary hypertension is a potentially life-threatening condition caused by high blood pressure in the arteries of the lungs (pulmonary arteries), which leads to damage to the right side of the heart. In pulmonary hypertension the walls of the pulmonary arteries become thick and stiff, and cannot expand as well to allow blood to flow through. The reduced blood flow into your lungs makes it harder for the right side of your heart to pump blood through the pulmonary arteries. This increase in pressure can damage your heart. If the right side of your heart has to continually work harder, it can gradually become weaker. This can lead to heart failure. Pulmonary hypertension can also cause other symptoms such as shortness of breath, chest pain, tiredness, a racing heartbeat (palpitations), swelling (edema) in the legs, ankles, feet or tummy (abdomen) and lightheadedness. These symptoms often get worse during exercise, which can limit your ability to take part in physical activities.

Pulmonary hypertension can occur alone or be caused by another disease or condition 59:

- One type of pulmonary hypertension is pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is caused by changes in the smaller branches of the pulmonary arteries.

- Left heart diseases, such as left heart failure, which may be caused by high blood pressure throughout your body or coronary heart disease

- Other heart and blood vessel diseases such as congenital (inherited) heart defects

- Lung diseases or a shortage of oxygen in the body (hypoxia)

- Blood clots that cause narrowing or a blockage in the pulmonary arteries

- Other medical conditions such as liver disease, sickle cell disease or connective tissue disorders like scleroderma

Several factors can increase your risk of developing pulmonary hypertension:

- Age: Pulmonary hypertension can occur at any age, but your risk increases as you get older. The condition is usually diagnosed between ages 30 and 60.

- Environment: You may be at an increased risk of pulmonary hypertension if you have or are exposed to asbestos or certain infections caused by parasites.

- Family history and genetics: Certain genetic disorders, such as Down syndrome, congenital heart disease, and Gaucher disease, can increase your risk of pulmonary hypertension. A family history of blood clots also increases your risk.

- Lifestyle habits: Unhealthy lifestyle habits such as smoking and illegal drug use can raise your risk of developing pulmonary hypertension.

- Medicine: Some prescribed medicines used to treat cancer and depression may increase your risk of pulmonary hypertension.

- Sex: Pulmonary hypertension is more common in women than in men. Pulmonary hypertension with certain types of heart failure is also more common in women.

In the United States, the most common cause of pulmonary hypertension is left heart disease, such as left heart failure. There are several other medical conditions and environmental factors that can increase the risk of developing pulmonary hypertension. As a disease on its own pulmonary hypertension is rare – affecting between 10 and 57 people per million – but it leads to heart damage. Pulmonary hypertension can lead to death from heart failure within a few years. Some patients will need a lung transplant, or heart-lung transplant.

To diagnose pulmonary hypertension, your doctor may ask you questions about your medical history and do a physical exam. Based on your symptoms and risk factors, your doctor may refer you to a lung specialist (pulmonologist) or a heart and blood vessel specialist (cardiologist). Your doctor will diagnose you with pulmonary hypertension if tests show higher-than-normal pressure in the arteries of the lungs (pulmonary arteries).

The most common tests that doctors use to diagnose pulmonary hypertension is to measure the pressure in your pulmonary arteries using cardiac catheterization and echocardiography. Normal pressure in the pulmonary arteries is between 11 and 20 mm Hg. If the pressure is too high, you may have pulmonary hypertension. A pressure of 25 mmHg or greater measured by cardiac catheterization or 35 to 40 mmHg or greater on echocardiography suggests pulmonary hypertension.

Other tests use to diagnose pulmonary hypertension may include:

- Blood tests look for blood clots, stress on the heart, or anemia.

- Heart imaging tests, such as cardiac MRI, take detailed pictures of the structure and functioning of the heart and surrounding blood vessels.

- Lung imaging tests, such as chest X-ray, looks at the size and shape of the heart and surrounding blood vessels, including the pulmonary arteries.

- Electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG) looks for changes in the electrical activity of your heart. This can help detect if certain parts of the heart are damaged or working too hard. In pulmonary hypertension, the heart can become overworked due to damage or changes in the pulmonary arteries.

Pulmonary hypertension treatment

Treatments for pulmonary hypertension will depend on the cause of the condition. Pulmonary hypertension usually gets worse over time. Left untreated, it may cause heart failure, which can be fatal, so it’s important treatment is started as soon as possible.

Many times, there is not a cure for pulmonary hypertension, but your healthcare provider can work with you to manage the symptoms and help you manage your condition. This may include medicine or healthy lifestyle changes.

If another condition is causing pulmonary hypertension, the underlying condition should be treated first. This can sometimes prevent the pulmonary arteries being permanently damaged.

Medicines to treat pulmonary hypertension may include:

- Anticoagulant medicines or blood thinners to prevent blood clots in people whose pulmonary hypertension is caused by chronic blood clots in the lungs. These blood thinners also can help some people who have pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), heart failure, or other risk factors for blood clots.

- Digitalis or digoxin to control the rate blood is pumped throughout the body. Digoxin can improve your symptoms by strengthening your heart muscle contractions and slowing down your heart rate

- Vasodilator therapy to relax blood vessels and lower blood pressure in the pulmonary artery most affected in people who have pulmonary arterial hypertension. This includes calcium channel blockers such as nifedipine, diltiazem, nicardipine and amlodipine, as well as newer groups of medicines called endothelin receptor antagonists (bosentan, ambrisentan and macitentan), phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors (sildenafil and tadalafil), prostaglandins (epoprostenol, iloprost and treprostinil) and soluble guanylate cyclase stimulators (riociguat).

- Diuretics (water tablets) to remove excess fluid as a result of heart failure

Home oxygen treatment may also be prescribed if the level of oxygen in your blood is low.

Your doctor may recommend a procedure or surgery to treat pulmonary hypertension:

- Pulmonary endarterectomy – a surgery to remove old blood clots from the pulmonary arteries in the lungs of people with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension.

- Balloon pulmonary angioplasty – a new procedure where a tiny balloon is guided into the pulmonary arteries and inflated for a few seconds to push the blockage aside and restore blood flow to the lung; it may be considered if pulmonary endarterectomy is not suitable, and has been shown to lower blood pressure in the lung arteries, improve breathing, and increase the ability to exercise.

- Atrial septostomy to decrease pressure in the right heart chambers and improve the output of the left heart and oxygenation of the blood. In this procedure, a small hole is made in the wall between the right and left atria to allow blood to flow from the right to the left atrium.

- Transplant surgery – in severe cases, a lung transplant or a heart-lung transplant may be needed; this type of surgery is rarely used because effective medicine is available

Your doctor may also recommend medicines or procedures to treat the condition that is causing your pulmonary hypertension:

- Blood pressure medicines such as angiotensin-converting enzymes inhibitors (ACE-I), beta blockers, or calcium channel blockers (CCB) when left heart disease is the cause

- Blood transfusions or hydroxyurea to treat sickle cell disease

- Heart valve repair

- Iron supplements to increase blood iron levels and improve anemia

The outlook for pulmonary hypertension varies, depending on factors such as:

- what’s causing it

- how quickly it’s diagnosed

- how advanced your symptoms are

- whether you have another underlying health condition

The specialist in charge of your care will be able to give you more detailed information.

Having pulmonary hypertension can affect your ability to carry out everyday activities. Your doctor may recommend the following to monitor your condition and treatment response:

- Six-minute walk test to monitor your ability to exercise

- Blood tests to check hemoglobin, iron, and electrolyte levels; kidney, liver, and thyroid function; your blood’s ability to clot; and signs of stress on the heart

- Cardiac catheterization

- Cardiac MRI to monitor your heart’s size and how well it is working

- Chest X-ray

- Echocardiography to monitor your heart’s size and how well it is working, and measure the pressure in your right heart chambers

- Electrocardiogram to check for irregular heartbeats

- Lung function tests to check for any change in your lung function

If your pulmonary hypertension is severe or does not respond to treatment, your doctor may talk to you about a lung transplant or a heart and lung transplant.

Portal hypertension

Portal hypertension is abnormally high blood pressure in the portal vein (the large vein that brings blood from the intestine to the liver) and its branches. The portal vein receives blood from the entire intestine and from the spleen, pancreas, and gallbladder and carries that blood to the liver. After entering the liver, the portal vein divides into right and left branches and then into tiny channels that run through the liver. When blood leaves the liver, it flows back into the general circulation through the hepatic vein.

Portal hypertension is a common complication of cirrhosis and, less commonly, alcoholic hepatitis. When the liver becomes severely scarred, it’s harder for blood to move through it. This leads to an increase in the pressure of blood around the intestines.

The blood must also find a new way to return to your heart. It does this by using smaller blood vessels. Most often it goes through blood vessels in your stomach, esophagus, or intestines. But these blood vessels are not designed to carry the weight of blood, so they can become stretched out and weakened. These weakened blood vessels are known as varices. If the blood pressure rises to a certain level, it can become too high for the varices to cope with, causing the walls of the varices to split and bleed. Bleeding from esophageal varices is a medical emergency and can be fatal. The bleeding can be rapid and massive, causing you to vomit blood and pass stools that are very dark or tar-like. Alternatively, long-term bleeding can lead to anemia.

Usually, doctors can recognize portal hypertension based on symptoms and findings during the physical examination. Doctors can usually feel an enlarged spleen when they examine the abdomen. They can detect fluid in the abdomen by noting abdominal swelling and by listening for a dull sound when tapping (percussing) the abdomen.

Ultrasonography may be used to examine blood flow in the portal vein and nearby blood vessels and to detect fluid in the abdomen. Ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or computed tomography (CT) can be used to look for and examine collateral vessels.

Less commonly, a catheter is inserted through an incision in the neck and threaded through blood vessels into the liver to measure pressure in the portal blood vessels.

Treatment of portal hypertension

- For bleeding from esophageal varices, drugs to slow bleeding, blood transfusions, and/or endoscopy. Drugs such as vasopressin or octreotide may be given intravenously to make the bleeding veins contract and thus slow the bleeding. Blood transfusions are given to replace lost blood. Doctors usually use a flexible viewing tube (endoscope), inserted through the mouth into the esophagus to confirm that the bleeding is from varices. Working through the endoscope, doctors can use rubber bands to tie off the veins or hardened chemicals in the swollen blood vessels to block them off. To reduce the risk of bleeding from esophageal varices, doctors may try to reduce pressure in the portal vein. One way is to give beta-blocker drugs, such as timolol, propranolol, nadolol, or carvedilol.

- Sometimes surgery to reroute blood flow (portosystemic shunting). Portosystemic shunting may be done to connect the portal vein or one of its branches to a vein in the general circulation. This procedure reroutes most of the blood that normally goes to the liver so that it bypasses the liver. This bypass (called a shunt) lowers pressure in the portal vein because pressure is much lower in the general circulation. There are various types of portosystemic shunt procedures. In one type, called transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting (TIPS), doctors, using x-rays for guidance, insert a catheter with a needle into a vein in the neck and thread it to veins in the liver. The catheter is used to create a passage (shunt) that connects the portal vein (or one of its branches) directly with one of the hepatic veins. Less commonly, portosystemic shunts are created surgically.

- If surgery doesn’t work or you have liver failure, you may need a liver transplant.

Intracranial hypertension

Intracranial hypertension is a general term for the neurological disorders in which cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure within the skull is too high. “Intracranial” means “within the skull.” “Hypertension” means “high fluid pressure.” Intracranial hypertension in adults is generally defined as intracranial pressure that reaches 250 millimeters of water (mm H2O) or above. Old names for intracranial hypertension include Benign Intracranial Hypertension and Pseudotumor Cerebri 60.

For adults:

- Normal intracranial pressure readings are generally below 200 mm H2O

- Borderline high intracranial pressure readings are between 200-250 mm H2O

- Anything above 250 mm H2O is considered a high pressure reading.

For young children:

- Anything above 200 mm H2O is considered a high pressure reading.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is one of three major components inside the skull; the other two are the blood supply (the arteries and veins known as the vasculature) that the brain requires to function and the brain itself. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) has several important functions. It cushions the brain within the skull, transports nutrients to brain tissue and carries waste away. CSF is produced at a site within the brain called the choroid plexus, which generates about 400-500 ml (one pint) of the fluid each day or approximately 0.3 cc per minute. The total volume of CSF in the skull at any given time is around 140 ml. That means the body produces, absorbs and replenishes the total volume of CSF about 3-4 times daily.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flows from the choroid plexus through the brain’s four, interconnecting ventricles before finally entering the sub-arachnoid space, which surrounds the brain and spinal cord. The fluid then flows over the brain and spinal cord and is eventually absorbed into the venous blood system through tiny, one-way channels called arachnoid granulations or villi. When this continuous cycle of CSF production, circulation and absorption functions normally, it regulates the volume of CSF in the skull and the fluid pressure remains at a constant level. In other words, the CSF production rate remains equal to the CSF absorption rate. Intracranial pressure is determined by the three main components within the skull —brain tissue, blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)— working together. Under normal circumstances, these three components maintain a dynamic equilibrium. In order for this balance to be maintained, it is believed that CSF, which is produced at approximately 0.3 cc per minute, must also exit the skull at the same rate. But when the body cannot effectively absorb or drain CSF, intracranial pressure increases within the skull, which is made of bone and cannot expand. And since the brain and the vasculature can only be compressed so far, intracranial pressure must rise. Intracranial hypertension in adults is defined as CSF pressure at 250 mmH2O or above. In chronic intracranial hypertension, the exiting (or egress) of CSF is thought to be impaired while simultaneously the CSF productions continues, which leads to elevated intracranial pressure.

Intracranial hypertension can be divided into two categories:

- Acute intracranial hypertension

- Chronic intracranial hypertension

Acute intracranial hypertension often occurs as the result of severe head injury or intracranial bleeding from an aneurysm or a stroke. It is characterized by a very rapid onset after the initial injury and extremely high intracranial pressure that can be fatal. The underlying cause of acute intracranial hypertension is brain-swelling or intracranial bleeding into the sub-arachnoid space that surrounds the brain. In many cases, a piece of skull is surgically removed to accommodate brain swelling and lower intracranial pressure. This can be life-saving.

In contrast, chronic intracranial hypertension is a neurological disorder in which the increased cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure has generally arisen and remains elevated over a sustained period of time. It can either occur without a detectable cause (idiopathic intracranial hypertension or pseudotumor cerebri) or be triggered by an identifiable cause such as an underlying disease or disorder, injury, drug or cerebral blood clot (secondary intracranial hypertension). Chronic intracranial hypertension is frequently a life-long illness with significant physical, financial and emotional impact. Chronic intracranial hypertension can cause both rapid and progressive changes in vision. Vision loss and blindness due to chronic intracranial hypertension are usually related to optic nerve swelling (papilledema), which is caused by high CSF pressure on the nerve and its blood supply. In addition, individuals with chronic intracranial hypertension often suffer severe pain. The most common form is a chronic headache, which is generally unresponsive to the most potent pain medication.

Anyone can develop chronic intracranial hypertension, regardless of age, gender, ethnicity, race or body type. While the chronic form of intracranial hypertension is not usually fatal, current treatments for the disorder can result in serious, sometimes life-threatening complications.

Researchers are eager to identify the mechanism that underlies chronic intracranial hypertension. While no one is sure why intracranial hypertension happens, some researchers believe that the answer may involve resistance or obstruction of CSF outflow through the exiting pathways from the brain.

Symptoms of chronic intracranial hypertension can include 61:

- Constant throbbing headaches that are generally nonspecific in location, type and frequency and can be associated with nausea and vomiting. Headaches may be worse in the morning, or when coughing or straining; it may improve when standing up

- Pulsatile tinnitus is a rhythmic or pulsating ringing heard in one or both ears.

- Horizontal double vision can be a sign of pressure on the 6th cranial nerve(s).

- Nonspecific radiating pain in the arms or legs (radicular pain).

- Transient obscurations of vision, which are temporary dimming or complete blacking out of vision. Your vision may become dark or “greyed out” for a few seconds at a time; this can be triggered by coughing, sneezing or bending down

- Visual field defects. These defects can occur in the central as well as the peripheral vision.

- Loss of color vision.

- Feeling and being sick

- Feeling sleepy

- Feeling irritable