Contents

- Small cell lung cancer

- Chest anatomy

- Human lungs

- Small Cell Lung Cancer causes

- Small Cell Lung Cancer Risk Factors

- Small Cell Lung Cancer prevention

- Small Cell Lung Cancer signs and symptoms

- Small Cell Lung Cancer Diagnosis

- Small Cell Lung Cancer Stages

- Small Cell Lung Cancer Survival Rates by Stage

- Small Cell Lung Cancer Treatment

- Small cell lung cancer prognosis

Small cell lung cancer

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) also called oat cell cancer, is a type of fast-growing, aggressive lung cancer that usually starts in the central airways and spreads quickly, often before symptoms appear 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9. Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) typically starts in the bronchi, the main airways in your chest. Almost all cases of small cell lung cancer (SCLC) are linked to smoking 10, 11, 12. Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) accounts for about 10% to 15% of lung cancers. The cancer cells are small, but they usually grow very quickly and create large tumors. Small cell lung cancers are grade 3 cancers also known as high-grade or poorly differentiated cancer, which mean that the cancer cells look very abnormal and are likely to grow and spread quickly. Small cell lung cancer is more responsive to chemotherapy and radiation therapy than other cell types of lung cancer 13, 14, 15. Platinum–etoposide-based chemotherapy combined with immunotherapy constitutes the standard treatment for patients with small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) 4. However, a cure is difficult to achieve because small cell lung cancer has a greater tendency to spread rapidly (metastasize) to other parts of your body, including your brain, liver, and bone by the time of diagnosis 16, 14, 17. The median survival rate seldom exceeds 1 year 9, 18. The overall 5 year survival rate for small cell lung cancer (SCLC) patients continues to be under 7% 16, 19. Each year, around 250,000 patients are diagnosed with small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) worldwide, with approximately 200,000 deaths resulting from small-cell lung cancer 9, 13, 18.

Approximately 60-70% of patients with small cell lung cancer (SCLC) have clinically disseminated or extensive disease at presentation 20. Extensive-stage small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is incurable. When given combination chemotherapy, patients with extensive-stage small cell lung cancer (SCLC) have a complete response rate of more than 20% and a median survival longer than 7 months; however, only 2% are alive at 5 years 21. For individuals with limited-stage small cell lung cancer (SCLC) that is treated with combination chemotherapy plus chest radiation, a complete response rate of 80% and survival of 17 months have been reported; 12-15% of patients are alive at 5 years 22.

Indicators of poor prognosis include the following 20:

- Relapsed disease

- Weight loss of greater than 10% of baseline body weight

- Poor performance status

- Hyponatremia 23

- Genome-wide association studies have identified single-nucleotide polymorphisms (eg, within the promoter region of YAP1 on chromosome 11q22) that may affect survival in patients with small cell lung cancer (SCLC) 24, 25.

There are currently 2 types of small cell lung cancer (SCLC) 26:

- Small cell carcinoma (SCLC): This is the most common form of small cell lung cancer.

- Combined small cell carcinoma (C-SCLC): Combined small cell carcinoma (C-SCLC) represents about 2% to 5% of all small cell carcinomas. Combined small cell carcinoma (C-SCLC) is a combination of small cell lung cancer cells with additional components from any of the non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) histological types. These usually include adenocarcinoma (ADC), squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) and less commonly spindle cell carcinoma or giant cell carcinoma 27. No minimum percentage of the additional component is required for a combined small cell carcinoma (C-SCLC) diagnosis with the exception of mixed large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) and small cell carcinoma (SCLC), where a minimum of 10% LCNEC component is required given the frequent presence of scattered large cells in surgically resected SCLC 27.

Patients diagnosed with combined small cell carcinoma (C-SCLC) are currently recommended to receive the same treatment as small cell carcinoma (SCLC) in the absence of clear evidence suggesting different strategies 28, 29.

Small cell lung cancers are also classified as neuroendocrine tumors 30, 31. You might also hear them called lung neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs). This means the same as lung neuroendocrine cancer. Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are rare tumors that develop in cells of the neuroendocrine system. In small cell lung cancer, the tumor starts in the neuroendocrine cells of the lung. Neuroendocrine cells are specialized cells that act like both nerve cells and endocrine cells, receiving signals from the nervous system (like nerve cells) and responding by releasing hormones (like endocrine cells), such as serotonin (5HT), gastrin-releasing peptide (GRP), neuron-specific enolase (NSE), and bombesin 16, 32. It is worth noting that calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), neural cell adhesion molecule 1 (NCAM1), and mammalian achaete-scute complex homolog 1 (MASH1/ASCL1) have significant functions in neuronal differentiation, and are prominently expressed in pulmonary neuroendocrine cells (PNECs) 16, 33.

There are 2 key groups of lung neuroendocrine cancer:

- Lung neuroendocrine tumors (NETs): Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) include the following:

- Low-grade typical carcinoid. Typical carcinoids are grade 1 cancers. Typical carcinoids are also called carcinoid tumors. They are slow growing and less likely to spread outside the lungs. The cancer cells look very like normal cells. Doctors also call these well differentiated cancers. Around 2 in every 100 lung cancers (around 2%) diagnosed in the US every year are typical carcinoids.

- Intermediate-grade atypical carcinoid. Atypical carcinoids are grade 2 cancers. Atypical carcinoids are also called carcinoid tumors. Doctors also call these moderately differentiated cancers. They behave somewhere between grade 1 and grade 3 cancers. They usually grow faster than typical carcinoids. And they are more likely to spread. The cancer cells look more abnormal. Fewer than 1 in every 100 lung cancers (1%) diagnosed in the US every year are atypical carcinoids.

- High-grade neuroendocrine tumors, including large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) and small cell lung cancer (SCLC).

- Lung neuroendocrine carcinomas (NECs) – these include small cell neuroendocrine carcinomas and large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas (LCNEC). Both neuroendocrine carcinomas are categorized as high-grade neoplasms, in contrast to typical carcinoid and atypical carcinoid neoplasms, which are low-grade and intermediate grade, respectively 30, 31.

- Small cell lung cancer arising from neuroendocrine cells forms one extreme of the spectrum of neuroendocrine carcinomas (NECs) of the lung.

- Large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas (LCNEC) are grade 3 cancers. They tend to grow quickly and are more likely to spread. The cancer cells look very abnormal. Doctors also call these cancers poorly differentiated cancers. Around 3 out of every 100 lung cancers (3%) diagnosed in the US every year are this type. They are linked to smoking.

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) and neuroendocrine carcinomas (NECs) are very different. So it is important to know which one you have. Talk to your doctor or cancer specialist if you are not sure.

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) primarily originates from lung neuroendocrine cells (PNECs), but can also develop from lung epithelial cells, including basal or club cells and cuboidal alveolar type 2 (AT2) cells in particular instances 4. Researchers have identified Tuft cells as potential progenitor cells in a specific subtype of small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) 16, 34. Tuft cells, also known as brush cells, are chemosensory cells that reside in the epithelial lining of the lungs 16, 35. The development of small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) is associated with loss-of-function mutations in genes such as tumor protein 53 (TP53) and retinoblastoma 1 (RB1) in lung neuroendocrine cells (PNECs), tuft, club, or AT2 cells 4.

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) was initially classified as a lymphosarcoma in 1879 by Harting and Hesse 36, 31; however, it was reclassified as tiny ‘oat cell’ carcinomas of the lung in 1926 31, 37. Since then, small cell lung cancer (SCLC) has been widely recognized as oat cell carcinoma 31, 38, 39. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumors, “small cell lung cancer is defined by light microscopy as a tumor with cells that have a small size, a round-to-fusiform shape, scant cytoplasm, finely granular nuclear chromatin and absent or inconspicuous nucleoli” 2. Necrosis may be extensive, and cells manifest a high mitotic rate. small cell lung cancers originate from epithelial cells, and up to 90% will express thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF1). Epithelial cell markers including cytokeratin can be used to distinguish small cell lung cancer from lymphoma and other neuroendocrine tumors.

Because of differences in clinical behavior, therapy, and epidemiology, small cell lung cancers are classified separately in the World Health Organization (WHO) revised classification 30, 40. Small cell lung cancer is now divided into small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and combined small-cell lung cancer (C-SCLC) 41. No minimum percentage of the additional component is required for a combined small cell lung cancer diagnosis with the exception of mixed large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) and small cell lung cancer, in which a 10% minimum large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) component is required 42.

Estimated new cases and deaths from lung cancer (non–small cell lung cancer and small cell lung cancer combined) in the United States in 2025 43, 43, 44:

- New cases: About 226,650 new cases of lung cancer (110,680 in men and 115,970 in women). The number of new lung cancer cases continues to decrease, partly because people are quitting smoking 45. However, in developing countries, non-small cell lung cancer cases are rising due to higher smoking rates and growing industrialization 46.

- Deaths: About 124,730 deaths from lung cancer (64,190 in men and 60,540 in women). Death rates for lung cancer are higher among the middle-aged and older populations. Lung and bronchus cancer is the first leading cause of cancer death in the United States. The death rate was 32.4 per 100,000 men and women per year based on 2018–2022 deaths, age-adjusted.

- 5-Year Relative Survival: 26.7%. Relative survival is an estimate of the percentage of patients who would be expected to survive the effects of their cancer. It excludes the risk of dying from other causes. Because survival statistics are based on large groups of people, they cannot be used to predict exactly what will happen to an individual patient. No two patients are entirely alike, and treatment and responses to treatment can vary greatly.

- Percentage of All Cancer Deaths: 20.4%. Lung cancer is by far the leading cause of cancer death, making up almost 20.4% of all cancer deaths. Each year, more people die of lung cancer than of colon, breast, and prostate cancers combined.

- The percent of lung and bronchus cancer deaths is highest among people aged 65–74. With the Median Age At Death 72 years of age.

- Rate of New Lung Cancer Cases and Deaths per 100,000: The rate of new cases of lung and bronchus cancer was 49 per 100,000 men and women per year. The death rate was 32.4 per 100,000 men and women per year. These rates are age-adjusted and based on 2017–2021 cases and 2018–2022 deaths.

- Lifetime Risk of Developing Lung Cancer: Approximately 5.7 percent of men and women will be diagnosed with lung and bronchus cancer at some point during their lifetime, based on 2018–2021 data.

- Prevalence of Lung Cancer: In 2021, there were an estimated 610,816 people living with lung and bronchus cancer in the United States.

Lung cancer mainly occurs in older people. About 2 out of 3 people diagnosed with lung cancer are 65 or older, while less than 2% are younger than 45. The average age at the time of diagnosis is about 70 47.

Figure 1. Lung cancer types

Footnotes: Overview of non-small cell lung cancer types of cancers that develop from the lung’s epithelial cells, with three main subtypes: adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and large cell carcinoma.

[Source 46 ]Figure 2. Small-cell lung cancer subtypes

Footnotes: Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) can be categorized into specific subtypes defined by the varying expression of 4 essential transcriptional regulators: achaete-scute homolog 1 (ASCL1; also referred to as ASH1) (SCLC-A subtype), neurogenic differentiation factor 1 (NEUROD1) (SCLC-N subtype), yes-associated protein 1 (YAP1) (SCLC-Y subtype), and POU class 2 homeobox 3 (POU2F3) (SCLC-P subtype). The most recent nomenclature designates a subtype known as ‘inflamed’ small-cell lung cancer (SCLC-I) 19, 48, 49, 13, 16, 50, 51. The relationship among these subtype-specific transcription factors encompasses varying levels of neuroendocrine differentiation. In a comprehensive multiomic evaluation of 437 small cell lung cancers, primarily metastatic, the overall distribution of samples was as follows: 35.7% coming from the A subgroup, 17.6% coming from the N subgroup, 6.4% coming from the P subgroup, 21.1% coming from the Y subgroup, and 19.2% coming from mixed subgroups 12, 52. The A and N subtypes are typically associated with elevated expression of neuroendocrine markers, while the P and Y subtypes exhibit reduced levels of these markers 12.

[Source 4 ]Chest anatomy

Your chest cavity also called the thoracic cavity is formed by the ribs, the muscles of the chest, the sternum (breastbone), and the thoracic portion of the vertebral column. Within your thoracic cavity are 3 smaller cavities: (a) 2 pleural cavities (fluid-filled spaces one around each lung), your left pleural cavity (holds your left lung) and your right pleural cavity (holds your right lung) and (b) a central portion of your thoracic cavity between your lungs called the mediastinum (media- = middle; -stinum = partition). The mediastinum is the central portion of your thoracic cavity between your lungs, extending from the base of your neck (from your first rib and sternum) to the diaphragm. The mediastinum contains your heart (pericardial cavity, peri- = around; -cardial = heart, a fluid-filled space that surrounds your heart), the major blood vessels connected to your heart and lungs, the trachea (windpipe) and bronchi, the esophagus (foodpipe), the thymus, and lymph nodes but not your lungs. Your right and left lungs are on either side of the mediastinum. The diaphragm is a dome-shaped muscle that separates the thoracic cavity from the abdominopelvic cavity.

Your mediastinum is divided into several parts, which researchers call compartments. The traditional or classical model divides your mediastinum into four parts:

- Superior mediastinum: The top part, located superior to (above) your heart.

- Anterior mediastinum: The part anterior to (in front of) your heart, between your heart and your sternum (breastbone).

- Middle mediastinum: The part that contains your heart.

- Posterior mediastinum: The part posterior to (behind) your heart.

A membrane is a thin, pliable tissue that covers, lines, partitions, or connects internal organs (viscera). One example is a slippery, double-layered membrane associated with body cavities that does not open directly to the exterior called a serous membrane. Serous membrane covers your internal organs (viscera) within the thoracic and abdominal cavities and also lines the walls of the thorax and abdomen. The parts of a serous membrane are (1) the parietal layer (outer layer), a thin epithelium that lines the walls of the cavities, and (2) the visceral layer (inner layer), a thin epithelium that covers and adheres to the viscera within the cavities. Between the two layers is a potential space that contains a small amount of lubricating fluid (serous fluid). The fluid allows the internal organs (viscera) to slide somewhat during movements, such as when the lungs inflate and deflate during breathing.

Within the right and left sides of your thoracic cavity (chest cavity), the compartments that contain your lungs, on either side of the mediastinum, are lined with a membrane called the parietal pleura (outer serous membrane) lining the inside of your rib cage (parietal pleura lines the chest wall) and covering the superior surface of the diaphragm. A similar membrane, called the visceral pleura (inner serous membrane), clings to the surface of your lungs forming the external surface of your lung. The visceral (inner) and parietal (outer) pleural membranes are separated only by a thin film of watery fluid called serous fluid, which is secreted by the parietal and visceral pleural membranes. Although no actual space normally exists between the parietal (outer) and visceral (inner) pleural membranes, the potential space between them is called the pleural cavity. The parietal pleura (outer membrane) and visceral pleura (inner membrane) slide with little friction across the cavity walls as your lungs move, expand and collapse during respiration.

Figure 3. Chest cavity

Footnote: The black dashed lines indicate the borders of the mediastinum.

Figure 4. Mediastinum

Human lungs

The lungs are soft, spongy, cone-shaped organs in the thoracic (chest) cavity. The lungs consist largely of air tubes and spaces. The balance of the lung tissue, its stroma, is a framework of connective tissue containing many elastic fibers. As a result, the lungs are light, soft, spongy, elastic organs that each weigh only about 0.6 kg (1.25 pounds). The elasticity of healthy lungs helps to reduce the effort of breathing.

The left and right lungs are situated in the left and right pleural cavities inside the thoracic cavity. They are separated from each other by the heart and other structures of the mediastinum, which divides the thoracic cavity into two anatomically distinct chambers. As a result, if trauma causes one lung to collapse, the other may remain expanded. Below the lungs, a thin, dome-shaped muscle called the diaphragm separates the chest from the abdomen. When you breathe, the diaphragm moves up and down, forcing air in and out of the lungs. The thoracic cage encloses the rest of the lungs.

Each lung occupies most of the space on its side of the thoracic cavity. A bronchus and some large blood vessels suspend each lung in the cavity. These tubular structures enter the lung on its medial surface.

Parietal refers to a membrane attached to the wall of a cavity; visceral refers to a membrane that is deeper—toward the interior—and covers an internal organ, such as a lung. Within the thoracic (chest) cavity, the compartments that contain the lungs, on either side of the mediastinum, are lined with a membrane called the parietal pleura. A similar membrane, called the visceral pleura, covers each lung.

The parietal and visceral pleural membranes are separated only by a thin film of watery fluid (serous fluid), which they secrete. Although no actual space normally exists between these membranes, the potential space between them is called the pleural cavity.

A thin lining layer called the pleura surrounds the lungs. The pleura protects your lungs and helps them slide back and forth against the chest wall as they expand and contract during breathing. A layer of serous membrane, the visceral pleura, firmly attaches to each lung surface and folds back to become the parietal pleura. The parietal pleura, in turn, borders part of the mediastinum and lines the inner wall of the thoracic cavity and the superior surface of the diaphragm.

In certain conditions, the pleural cavities may fill with air (pneumothorax), blood (hemothorax), or pus. Air in the pleural cavities, most commonly introduced in a surgical opening of the chest or as a result of a stab or gunshot wound, may cause the lungs to collapse. This collapse of a part of a lung, or rarely an entire lung, is called atelectasis. The goal of treatment is the evacuation of air (or blood) from the pleural space, which allows the lung to reinflate. A small pneumothorax may resolve on its own, but it is oft en necessary to insert a chest tube to assist in evacuation.

The thoracic (chest) cavity is divided by a thick wall called the mediastinum. This is the region between the lungs, extending from the base of the neck to the diaphragm. It is occupied by the heart, the major blood vessels connected to it, the esophagus, the trachea and bronchi, and a gland called the thymus.

Each lung is a blunt cone with the tip, or apex, pointing superiorly. The apex on each side extends into the base of the neck, superior to the first rib. The broad concave inferior portion, or base, of each lung rests on the superior surface of the diaphragm.

On the medial (mediastinal) surface of each lung is an indentation, the hilum, through which blood vessels, bronchi, lymphatic vessels, and nerves enter and exit the lung. Collectively, these structures attach the lung to the mediastinum and are called the root of the lung. The largest components of this root are the pulmonary artery and veins and the main (primary) bronchus. Because the heart is tilted slightly to the left of the median plane of the thorax, the left and right lungs differ slightly in shape and size.

Within each root and located in the hilum are:

- a pulmonary artery,

- two pulmonary veins,

- a main bronchus,

- bronchial vessels,

- nerves, and

- lymphatics.

Generally, the pulmonary artery is superior at the hilum, the pulmonary veins are inferior, and the bronchi are somewhat posterior in position. On the right side, the lobar bronchus to the superior lobe branches from the main bronchus in the root, unlike on the left where it branches within the lung itself, and is superior to the pulmonary artery.

Figure 5. Lungs anatomy

Figure 6. Hilum (roots) of the lungs

Several deep fissures divide the two lungs into different patterns of lobes.

- The left lung is divided into two lobes, the superior lobe and the inferior lobe, by the oblique fissure. The left lung is somewhat smaller than the right and has a cardiac notch, a deviation in its anterior border that accommodates the heart.

- The right lung is partitioned into three lobes, the superior, middle, and inferior lobes, by the oblique and horizontal fissures.

Each lung lobe is served by a lobar (secondary) bronchus and its branches. Each of the lobes, in turn, contains a number of bronchopulmonary segments separated from one another by thin partitions of dense connective tissue. Each segment receives air from an individual segmental (tertiary) bronchus. There are approximately ten bronchopulmonary segments arranged in similar, but not identical, patterns in each of the two lungs.

The bronchopulmonary segments have clinical significance in that they limit the spread of some diseases within the lung, because infections do not easily cross the connective tissue partitions between them. Furthermore, because only small veins span these partitions, surgeons can neatly remove segments without cutting any major blood vessels.

The smallest subdivision of the lung that can be seen with the naked eye is the lobule. Appearing on the lung surface as hexagons ranging from the size of a pencil eraser to the size of a penny, each lobule is served by a bronchiole and its branches. In most city dwellers and in smokers, the connective tissue that separates the individual lobules is blackened with carbon.

Each lung has a half-cone shape, with a base, apex, two surfaces, and three borders.

- The base sits on the diaphragm.

- The apex projects above rib I and into the root of the neck.

- The two surfaces-the costal surface lies immediately adjacent to the ribs and intercostal spaces of the thoracic wall. The mediastinal surface lies against the mediastinum anteriorly and the vertebral column posteriorly and contains the comma-shaped hilum of the lung, through which structures enter and leave.

- The three borders-the inferior border of the lung is sharp and separates the base from the costal surface. The anterior and posterior borders separate the costal surface from the medial surface. Unlike the anterior and inferior borders, which are sharp, the posterior border is smooth and rounded.

Right lung

The right lung has three lobes and two fissures. Normally, the lobes are freely movable against each other because they are separated, almost to the hilum, by invaginations of visceral pleura. These invaginations form the fissures:

- The oblique fissure separates the inferior lobe (lower lobe) from the superior lobe and the middle lobe of the right lung.

- The horizontal fissure separates the superior lobe (upper lobe) from the middle lobe.

The approximate position of the oblique fissure on a patient, in quiet respiration, can be marked by a curved line on the thoracic wall that begins roughly at the spinous process of the vertebra TIV level of the spine, crosses the fifth interspace laterally, and then follows the contour of rib VI anteriorly.

The horizontal fissure follows the fourth intercostal space from the sternum until it meets the oblique fissure as it crosses rib V.

The orientations of the oblique and horizontal fissures determine where clinicians should listen for lung sounds from each lobe. The largest surface of the superior lobe is in contact with the upper part of the anterolateral wall and the apex of this lobe proj ects into the root of the neck. The surface of the middle lobe lies mainly adjacent to the lower anterior and lateral wall. The costal surface of the inferior lobe is in contact with the posterior and inferior walls.

The medial surface of the right lung lies adjacent to a number of important structures in the mediastinum and the root of the neck. These include the:

- heart,

- inferior vena cava,

- superior vena cava,

- azygos vein, and

- esophagus.

The right subclavian artery and vein arch over and are related to the superior lobe of the right lung as they pass over the dome of the cervical pleura and into the axilla.

Left lung

The left Iung is smaller than the right lung and has two lobes separated by an oblique fissure. The oblique fissure of the left lung is slightly more oblique than the corresponding fissure of the right lung. During quiet respiration, the approximate position of the left oblique fissure can be marked by a curved line on the thoracic wall that begins between the spinous processes of thoracic vertebrae 3 (T3) and thoracic vertebrae 4 (TIV), crosses the fifth interspace laterally, and follows the contour of 6th rib anteriorly.

As with the right lung, the orientation of the oblique fissure determines where to listen for lung sounds from each lobe. The largest surface of the superior lobe is in contact with the upper part of the anterolateral wall, and the apex of this lobe proj ects into the root of the neck. The costal surface of the inferior lobe is in contact with the posterior and inferior walls.

The inferior portion o f the medial surface of the left lung, unlike the right lung, is notched because of the heart’s projection into the left pleural cavity from the middle mediastinum. From the anterior border of the lower part of the superior lobe a tongue-like extension (the lingula of the left lung) projects over the heart bulge.

The medial surface of the left lung lies adjacent to a number of important structures in the mediastinum and root of the neck. These include the:

- heart,

- aortic arch,

- thoracic aorta, and

- esophagus.

The left subclavian artery and vein arch over and are related to the superior lobe of the left lung as they pass over the dome of the cervical pleura and into the axilla.

Bronchial tree

The trachea is a flexible tube that extends from cervical spine C6 (vertebral level C VI) in the lower neck to thoracic spine T4-T5 (vertebral level T4 to T5) in the mediastinum where it bifurcates into a right and a left main bronchus. The trachea is held open by C-shaped transverse cartilage rings embedded in its wall the open part of the C facing posteriorly. The lowest tracheal ring has a hook-shaped structure, the carina, that projects backwards in the midline between the origins of the two main bronchi. The posterior wall of the trachea is composed mainly of smooth muscle. Each main bronchus enters the root of a lung and passes through the hilum into the lung itself. The right main bronchus is wider and takes a more vertical course through the root and hilum than the left main bronchus. Therefore, inhaled foreign bodies tend to lodge more frequently on the right side than on the left.

The bronchial tree consists of branched airways leading from the trachea to the microscopic air sacs in the lungs. Its branches begin with the right and left main (primary) bronchi, which arise from the trachea at the level of the fifth thoracic vertebra. Each bronchus enters its respective lung. A short distance from its origin, each main bronchus divides into lobar (secondary) bronchi. The lobar bronchi branch into segmental (tertiary) bronchi, which supply bronchopulmonary segments. Within each bronchopulmonary segment, the segmental bronchi give rise to multiple generations of divisions of increasingly finer tubes and, ultimately, to bronchioles , which further subdivide to terminal bronchioles, respiratory bronchioles, and finally to very thin tubes called alveolar ducts. These ducts lead to thin-walled outpouchings called alveolar sacs. Alveolar sacs lead to smaller, microscopic air sacs called alveoli (singular, alveolus), which lie within capillary networks. The alveoli are the sites of gas exchange between the inhaled air and the bloodstream.

The structure of a bronchus is similar to that of the trachea, but the tubes that branch from it have less cartilage in their walls, and the bronchioles lack cartilage. As the cartilage diminishes, a layer of smooth muscle surrounding the tube becomes more prominent. This muscular layer persists even in the smallest bronchioles, but only a few muscle cells are associated with the alveolar ducts.

The absence of cartilage in the bronchioles allows their diameters to change in response to contraction of the smooth muscle in their walls, similar to what happens with arterioles of the cardiovascular system. Part of the “fight-or-flight” response, triggered by the sympathetic nervous system, is bronchodilation, in which the smooth muscle relaxes and the airways become wider and allow more airflow. The opposite, bronchoconstriction, occurs when the smooth muscle contracts and it becomes difficult to move air in and out of the lungs. Bronchoconstriction can occur with allergies. Asthma is an extreme example of bronchoconstriction.

The mucous membranes of the bronchial tree continue to filter the incoming air, and the many branches of the tree distribute the air to alveoli throughout the lungs. The alveoli, in turn, provide a large surface area of thin simple squamous epithelial cells through which gases are easily exchanged. Oxygen diffuses from the alveoli into the blood in nearby capillaries, and carbon dioxide diffuses from the blood into the alveoli.

Figure 7. Bronchial tree of the lungs

Bronchopulmonary segments

A bronchopulmonary segment is the area of lung supplied by a segmental bronchus and its accompanying pulmonary artery branch. Tributaries of the pulmonary vein tend to pass intersegmentally between and around the margins of segments. Each bronchopulmonary segment is shaped like an irregular cone, with the apex at the origin of the segmental bronchus and the base projected peripherally onto the surface of the lung.

A bronchopulmonary segment is the smallest functionally independent region of a lung and the smallest area of lung that can be isolated and removed without affecting adjacent regions.

There are ten bronchopulmonary segments in each lung; some of them fuse in the left lung.

Figure 8. Bronchopulmonary segments

Lung Alveoli

Each human lung is a spongy mass composed of 150 million little sacs, the alveoli. These provide about 70 m², per lung, of gas-exchange surface—about equal to the floor area of a handball court or a room about 8.4 m (25 ft) square.

An alveolus is a pouch about 0.2 to 0.5 mm in diameter. Thin, broad cells called squamous (type I) alveolar cells cover about 95% of the alveolar surface area. Their thinness allows for rapid gas diffusion between the air and blood. The other 5% is covered by round to cuboidal great (type II) alveolar cells. Even though they cover less surface area, these considerably outnumber the squamous alveolar cells.

Great (type II) alveolar cells have two functions:

- They repair the alveolar epithelium when the squamous cells are damaged; and

- They secrete pulmonary surfactant, a mixture of phospholipids and protein that coats the alveoli and smallest bronchioles and prevents the bronchioles from collapsing when one exhales.

The most numerous of all cells in the lung are alveolar macrophages (dust cells), which wander the lumens of the alveoli and the connective tissue between them. These cells keep the alveoli free of debris by phagocytizing dust particles that escape entrapment by mucus in the higher parts of the respiratory tract. In lungs that are infected or bleeding, the macrophages also phagocytize bacteria and loose blood cells. As many as 100 million alveolar macrophages perish each day as they ride up the mucociliary escalator to be swallowed and digested, thus ridding the lungs of their load of debris.

Each alveolus is surrounded by a web of blood capillaries supplied by small branches of the pulmonary artery. The barrier between the alveolar air and blood, called the respiratory membrane, consists only of the squamous alveolar cell, the squamous endothelial cell of the capillary, and their shared basement membrane. These have a total thickness of only 0.5 μm, just 1/15 the diameter of a single red blood cell.

It is very important to prevent fluid from accumulating in the alveoli, because gases diffuse too slowly through liquid to sufficiently aerate the blood. Except for a thin film of moisture on the alveolar wall, the alveoli are kept dry by the absorption of excess liquid by the blood capillaries. The mean blood pressure in these capillaries is only 10 mm Hg compared to 30 mm Hg at the arterial end of the average capillary elsewhere. This low blood pressure is greatly overridden by the oncotic pressure that retains fluid in the capillaries, so the osmotic uptake of water overrides filtration and keeps the alveoli free of fluid. The lungs also have a more extensive lymphatic drainage than any other organ in the body. The low capillary blood pressure also prevents rupture of the delicate respiratory membrane.

Figure 9. Lungs alveoli

Note: (a) Clusters of alveoli and their blood supply. (b) Structure of an alveolus. (c) Structure of the respiratory membrane.

How your lungs work

Your lungs have a system of tubes that carry oxygen in and out as you breathe. The windpipe divides into two tubes, the right bronchus and left bronchus. These split into smaller tubes called secondary bronchi. They split again to make smaller tubes called bronchioles. The bronchioles have small air sacs at the end called alveoli.

In the air sacs, oxygen passes into your bloodstream from the air breathed in. Your bloodstream carries oxygen to all the cells in your body. At the same time carbon dioxide passes from your bloodstream into the air sacs. This waste gas is removed from the body as you breathe out.

Small Cell Lung Cancer causes

Scientists don’t know what causes each case of lung cancer. But they do know many of the risk factors for these cancers and how some of them can cause cells to become cancerous.

Smoking

Tobacco smoking is by far the leading cause of small cell lung cancer. Most small cell lung cancer deaths are caused by smoking or exposure to secondhand smoke, with only about 2% of cases arising in never-smokers 53. Patients with small cell lung cancer should be encouraged to stop smoking, as smoking cessation is associated with improved survival 54.

Smoking is clearly the strongest risk factor for lung cancer, but it often interacts with other factors. Smokers exposed to other known risk factors such as radon and asbestos are at even higher risk. Not everyone who smokes gets lung cancer, so other factors like genetics probably play a role as well.

Lung cancer in non-smokers

It is rare for someone who has never smoked to be diagnosed with small cell lung cancer, but it can happen. Lung cancer in non-smokers can be caused by exposure to radon, secondhand smoke, air pollution, or other factors. Workplace exposures to asbestos, diesel exhaust, or certain other chemicals can also cause lung cancers in some people who don’t smoke.

A small portion of lung cancers occur in people with no known risk factors for the disease. Some of these might just be random events that don’t have an outside cause, but others might be due to factors that we don’t yet know about.

Gene changes that may lead to lung cancer

Some of the risk factors for lung cancer can cause certain changes in the DNA of lung cells. These changes can lead to abnormal cell growth and, sometimes, cancer. DNA is the chemical in each of our cells that makes up our genes, which control how our cells function. We usually look like our parents because they are the source of our DNA. But DNA also can influence our risk for developing certain diseases, such as some kinds of cancer.

Some genes help control when cells grow, divide into new cells, and die:

- Genes that help cells grow, divide, or stay alive are called oncogenes.

- Genes that help control cell division or cause cells to die at the right time are called tumor suppressor genes.

Cancers can be caused by DNA changes that turn on oncogenes or turn off tumor suppressor genes.

Inherited gene changes

Some people inherit DNA mutations (changes) from their parents that greatly increase their risk for developing certain cancers. But inherited mutations alone are not thought to cause very many lung cancers.

Still, genes do seem to play a role in some families with a history of lung cancer. For example, some people seem to inherit a reduced ability to break down or get rid of certain types of cancer-causing chemicals in the body, such as those found in tobacco smoke. This could put them at higher risk for lung cancer.

Other people may inherit faulty DNA repair mechanisms that make it more likely they will end up with DNA changes. People with DNA repair enzymes that don’t work normally might be especially vulnerable to cancer-causing chemicals and radiation.

Researchers are developing tests that may help identify such people, but these tests are not yet used routinely. For now, doctors recommend that all people avoid tobacco smoke and other exposures that might increase their cancer risk.

Acquired gene changes

Gene changes related to SCLC are usually acquired during life rather than inherited. Acquired mutations in lung cells often result from exposure to factors in the environment, such as cancer-causing chemicals in tobacco smoke. But some gene changes may just be random events that sometimes happen inside a cell, without having an outside cause.

Acquired changes in certain genes, such as the TP53 and RB1 tumor suppressor genes, are thought to be important in the development of small cell lung cancer. Changes in these and other genes may also make some lung cancers more likely to grow and spread than others. Not all lung cancers share the same gene changes, so there are undoubtedly changes in other genes that have not yet been found.

Small Cell Lung Cancer Risk Factors

A risk factor is anything that affects your chance of getting a disease such as cancer. Different cancers have different risk factors. Some risk factors, like smoking, can be changed. Others, like a person’s age or family history, can’t be changed.

But having a risk factor, or even several, does not mean that you will get the disease. And some people who get the disease may have few or no known risk factors.

Several risk factors can make you more likely to develop lung cancer. These factors are related to the risk of lung cancer in general, so it’s possible that some of these might not apply to small cell lung cancer.

Tobacco smoke

Smoking is by far the leading risk factor for lung cancer. About 80% of all lung cancer deaths are thought to result from smoking, and this number is probably even higher for small cell lung cancer. It’s very rare for someone who has never smoked to have small cell lung cancer. The risk for lung cancer among smokers is many times higher than among non-smokers. The longer you smoke and the more packs per day you smoke, the greater your risk.

Cigar smoking and pipe smoking are almost as likely to cause lung cancer as cigarette smoking. Smoking low-tar or “light” cigarettes increases lung cancer risk as much as regular cigarettes. Smoking menthol cigarettes might increase the risk even more, as the menthol may allow smokers to inhale more deeply.

Secondhand smoke: If you don’t smoke, breathing in the smoke of others (called secondhand smoke or environmental tobacco smoke) can increase your risk of developing lung cancer. Secondhand smoke is thought to cause more than 7,000 deaths from lung cancer each year.

Exposure to radon

Radon is a radioactive gas that occurs naturally when uranium in soil and rocks breaks down. It cannot be seen, tasted, or smelled. According to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), radon is the second leading cause of lung cancer, and is the leading cause among non-smokers.

Outdoors, there is so little radon that it is not likely to be dangerous. But indoors, radon can become more concentrated. Breathing it in exposes your lungs to small amounts of radiation. This might increase your risk of lung cancer.

Homes and other buildings in nearly any part of the United States can have high indoor radon levels (especially in basements).

Exposure to asbestos

People who work with asbestos (such as in some mines, mills, textile plants, places that use insulation, and shipyards) are several times more likely to die of lung cancer. Lung cancer risk is much greater in workers exposed to asbestos who also smoke. It’s not clear how much low-level or short-term exposure to asbestos might raise lung cancer risk.

People exposed to large amounts of asbestos also have a greater risk of developing mesothelioma, a type of cancer that starts in the pleura (the lining surrounding the lungs).

In recent years, government regulations have greatly reduced the use of asbestos in commercial and industrial products. It’s still present in many homes and other older buildings, but it’s not usually considered harmful as long as it’s not released into the air by deterioration, demolition, or renovation.

Other cancer-causing substances in the workplace

Other carcinogens (cancer-causing substances) found in some workplaces that can increase lung cancer risk include:

- Radioactive ores such as uranium

- Inhaled chemicals such as arsenic, beryllium, cadmium, silica, vinyl chloride, nickel compounds, chromium compounds, coal products, mustard gas, and chloromethyl ethers

- Diesel exhaust

The government and industry have taken steps in recent years to help protect workers from many of these exposures. But the dangers are still there, so if you work around these products, be careful to limit your exposure whenever possible.

Air pollution

In cities, air pollution (especially near heavily trafficked roads) appears to raise the risk of lung cancer slightly. This risk is far less than the risk caused by smoking, but some researchers estimate that worldwide about 5% of all deaths from lung cancer may be due to outdoor air pollution.

Arsenic in drinking water

Studies of people in parts of Southeast Asia and South America with high levels of arsenic in their drinking water have found a higher risk of lung cancer. In most of these studies, the levels of arsenic in the water were many times higher than those typically seen in the United States, even in areas where arsenic levels are above normal. For most Americans who are on public water systems, drinking water is not a major source of arsenic.

Radiation therapy to the lungs

People who have had radiation therapy to the chest for other cancers are at higher risk for lung cancer, particularly if they smoke. Examples include people who have been treated for Hodgkin disease or women who get chest radiation after a mastectomy for breast cancer. Women who receive radiation therapy to the breast after a lumpectomy do not appear to have a higher than expected risk of lung cancer.

Personal or family history of lung cancer

If you have had lung cancer, you have a higher risk of developing another lung cancer.

Brothers, sisters, and children of those who have had lung cancer may have a slightly higher risk of lung cancer themselves, especially if the relative was diagnosed at a younger age. It’s not clear how much of this risk might be due to shared genes among family members and how much might be from shared household exposures (such as tobacco smoke or radon).

Researchers have found that genetics does seem to play a role in some families with a strong history of lung cancer. Research is ongoing in this area.

Certain dietary supplements

Studies looking at the possible role of vitamin supplements in reducing lung cancer risk have not been promising so far. In fact, 2 large studies found that smokers who took beta carotene supplements actually had an increased risk of lung cancer. The results of these studies suggest that smokers should avoid taking beta carotene supplements.

Factors with uncertain or unproven effects on lung cancer risk

Marijuana smoke

There are some reasons to think that smoking marijuana might increase lung cancer risk:

- Marijuana smoke contains tar and many of same the cancer-causing substances that are in tobacco smoke. (Tar is the sticky, solid material that remains after burning, which is thought to contain most of the harmful substances in smoke.)

- Marijuana cigarettes (joints) are typically smoked all the way to the end, where tar content is the highest.

- Marijuana is inhaled very deeply and the smoke is held in the lungs for a long time, which gives any cancer-causing substances more opportunity to deposit in the lungs.

- Because marijuana is still illegal in many places, it may not be possible to control what other substances it might contain.

Those who use marijuana tend to smoke fewer marijuana cigarettes in a day or week than the amount of tobacco consumed by cigarette smokers. The lesser amount smoked would make it harder to see an impact on lung cancer risk.

It’s been hard to study whether there is a link between marijuana and lung cancer because marijuana has been illegal in many places for so long, and it’s not easy to gather information about the use of illegal drugs.

Also, in studies that have looked at past marijuana use in people who had lung cancer, most of the marijuana smokers also smoked cigarettes. This can make it hard to know how much any increase in risk is from tobacco and how much might be from marijuana. More research is needed to know the cancer risks from smoking marijuana.

Talc and talcum powder

Talc is a mineral that in its natural form may contain asbestos. Some studies have suggested that talc miners and millers might have a higher risk of lung cancer and other respiratory diseases because of their exposure to industrial grade talc. But other studies have not found an increase in lung cancer rate.

Talcum powder is made from talc. By law since the 1970s, all home-use talcum products (baby, body, and facial powders) in the United States have been asbestos-free. The use of cosmetic talcum powder has not been found to increase lung cancer risk.

Small Cell Lung Cancer prevention

Not all lung cancers can be prevented. But there are things you can do that might lower your risk, such as changing the risk factors that you can control.

Stay away from tobacco

The best way to reduce your risk of lung cancer is not to smoke and to avoid breathing in other people’s smoke.

If you stop smoking before a cancer develops, your damaged lung tissue gradually starts to repair itself. No matter what your age or how long you’ve smoked, quitting may lower your risk of lung cancer and help you live longer.

Avoid radon

Radon is an important cause of lung cancer. You can reduce your exposure to radon by having your home tested and treated, if needed.

Avoid or limit exposure to cancer-causing chemicals

Avoiding exposure to known cancer-causing chemicals, in the workplace and elsewhere, might also be helpful. People working where these exposures are common should try to keep exposure to a minimum when possible.

Eat a healthy diet

A healthy diet with lots of fruits and vegetables may also help reduce your risk of lung cancer. Some evidence suggests that a diet high in fruits and vegetables may help protect against lung cancer in both smokers and non-smokers. But any positive effect of fruits and vegetables on lung cancer risk would be much less than the increased risk from smoking.

Trying to reduce the risk of lung cancer in current or former smokers by giving them high doses of vitamins or vitamin-like drugs has not been successful so far. In fact, some studies have found that supplements of beta-carotene, a nutrient related to vitamin A, appear to increase the rate of lung cancer in these people.

Some people who get lung cancer do not have any clear risk factors. Although we know how to prevent most lung cancers, at this time we don’t know how to prevent all of them.

Small Cell Lung Cancer signs and symptoms

Most lung cancers do not cause any symptoms until they have spread, but some people with early lung cancer do have symptoms. If you go to your doctor when you first notice symptoms, your cancer might be diagnosed at an earlier stage, when treatment is more likely to be effective.

Most of these symptoms are more likely to be caused by something other than lung cancer. Still, if you have any of these problems, it’s important to see your doctor right away so the cause can be found and treated, if needed. The most common symptoms of lung cancer are:

- A cough that does not go away or gets worse

- Coughing up blood or rust-colored sputum (spit or phlegm)

- Chest pain that is often worse with deep breathing, coughing, or laughing

- Hoarseness

- Weight loss and loss of appetite

- Shortness of breath

- Feeling tired or weak

- Infections such as bronchitis and pneumonia that don’t go away or keep coming back

- New onset of wheezing

When lung cancer spreads to other parts of the body, it may cause:

- Bone pain (like pain in the back or hips)

- Nervous system changes (such as headache, weakness or numbness of an arm or leg, dizziness, balance problems, or seizures), from cancer spread to the brain

- Yellowing of the skin and eyes (jaundice), from cancer spread to the liver

- Lumps near the surface of the body, due to cancer spreading to the skin or to lymph nodes (collection of immune system cells) such as those in the neck or above the collarbone

Some lung cancers can cause syndromes, which are groups of specific symptoms.

Horner syndrome

Cancers of the upper part of the lungs are sometimes called Pancoast tumors. These tumors are more likely to be non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) than small cell lung cancer (SCLC).

Pancoast tumors can affect certain nerves to the eye and part of the face, causing a group of symptoms called Horner syndrome:

- Drooping or weakness of one eyelid

- A smaller pupil (dark part in the center of the eye) in the same eye

- Reduced or absent sweating on the same side of the face

Pancoast tumors can also sometimes cause severe shoulder pain.

Superior vena cava syndrome

The superior vena cava is a large vein that carries blood from the head and arms back to the heart. It passes next to the upper part of the right lung and the lymph nodes inside the chest. Tumors in this area can press on the superior vena cava, which can cause the blood to back up in the veins. This can lead to swelling in the face, neck, arms, and upper chest (sometimes with a bluish-red skin color). It can also cause headaches, dizziness, and a change in consciousness if it affects the brain. While superior vena cava syndrome can develop gradually over time, in some cases it can become life-threatening, and needs to be treated right away.

Paraneoplastic syndromes

Some lung cancers make hormone-like substances that enter the bloodstream and cause problems with distant tissues and organs, even though the cancer has not spread to those tissues or organs. These problems are called paraneoplastic syndromes. Sometimes these syndromes may be the first symptoms of lung cancer. Because the symptoms affect other organs, patients and their doctors may first suspect that a disease other than lung cancer is causing them.

Some of the more common paraneoplastic syndromes associated with small cell lung cancer are:

- SIADH (syndrome of inappropriate anti-diuretic hormone): In this condition, the cancer cells make a hormone (ADH) that causes the kidneys to retain (hold) water. This lowers salt levels in the blood. Symptoms of SIADH can include fatigue, loss of appetite, muscle weakness or cramps, nausea, vomiting, restlessness, and confusion. Without treatment, severe cases may lead to seizures and coma.

- Cushing syndrome: In this condition, the cancer cells make ACTH, a hormone that makes the adrenal glands secrete cortisol. This can lead to symptoms such as weight gain, easy bruising, weakness, drowsiness, and fluid retention. Cushing syndrome can also cause high blood pressure and high blood sugar levels, or even diabetes.

- Nervous system problems: Small cell lung cancer can sometimes cause the body’s immune system to attack parts of the nervous system, which can lead to problems. One example is a muscle disorder called Lambert-Eaton syndrome. In this syndrome, muscles around the hips become weak. One of the first signs may be trouble getting up from a sitting position. Later, muscles around the shoulder may become weak. A rarer problem is paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration, which can cause loss of balance and unsteadiness in arm and leg movement, as well as trouble speaking or swallowing. Small cell lung cancer can also cause other nervous system problems, such as muscle weakness, sensation changes, vision problems, or even changes in behavior.

Again, many of these symptoms can also be caused by something other than lung cancer. Still, if you have any of these problems, it’s important to see your doctor right away so the cause can be found and treated, if needed.

Small Cell Lung Cancer Diagnosis

Screening can find some lung cancers, but most lung cancers are found because they are causing problems. If you have possible signs or symptoms of lung cancer, see your doctor, who will examine you and may order some tests. The actual diagnosis of lung cancer is made after looking at a sample of your lung cells under a microscope.

Medical history and physical exam

- Your doctor will ask about your medical history to learn about your symptoms and possible risk factors. You will also be examined for signs of lung cancer or other health problems.

If the results of your history and physical exam suggest you might have lung cancer, you will have tests to look for it. These could include imaging tests and/or biopsies of lung tissue.

Imaging tests to look for lung cancer

Imaging tests use x-rays, magnetic fields, sound waves, or radioactive substances to create pictures of the inside of your body. Imaging tests might be done for a number of reasons both before and after a diagnosis of lung cancer, including:

- To look at suspicious areas that might be cancer

- To learn if and how far cancer has spread

- To help determine if treatment is working

- To look for possible signs of cancer coming back after treatment

Chest x-ray

This is often the first test your doctor will do to look for any abnormal areas in the lungs. Plain x-rays of your chest can be done at imaging centers, hospitals, and even in some doctors’ offices. If the x-ray result is normal, you probably don’t have lung cancer (although some lung cancers may not show up on an x-ray). If something suspicious is seen, your doctor will likely order more tests.

Computed tomography (CT) scan

A CT scan combines many x-rays to make detailed cross-sectional images of your body.

A CT scan is more likely to show lung tumors than a routine chest x-ray. It can also show the size, shape, and position of any lung tumors and can help find enlarged lymph nodes that might contain cancer that has spread from the lung. Most people with small cell lung cancer (SCLC) will get a CT of the chest and abdomen to look at the lungs and lymph nodes, and to look for abnormal areas in the adrenal glands, liver, and other organs that might be from the spread of lung cancer. Some people will get a CT of the brain to look for cancer spread, but an MRI is more likely to be used when looking at the brain.

CT guided needle biopsy: If a suspected area of cancer is deep within your body, a CT scan can be used to guide a biopsy needle precisely into the suspected area.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan

Like CT scans, MRI scans show detailed images of soft tissues in the body. But MRI scans use radio waves and strong magnets instead of x-rays.

Most patients with SCLC will have an MRI scan of the brain to look for possible cancer spread, although a CT scan may be used instead. MRI may also be used to look for possible spread to the spinal cord if the patients have certain symptoms.

Positron emission tomography (PET) scan

For a PET scan, you are injected with a slightly radioactive form of sugar, which collects mainly in cancer cells. A special camera is then used to create a picture of areas of radioactivity in the body.

A PET scan can be a very important test if you appear to have early stage (or limited) SCLC. Your doctor can use this test to see if the cancer has spread to lymph nodes or other organs, which can help determine your treatment options. A PET scan can also give a better idea whether an abnormal area on a chest x-ray or CT scan might be cancer. PET scans are also useful if your doctor thinks the cancer may have spread but doesn’t know where.

PET/CT scan: Some machines can do both a PET scan and a CT scan at the same time. This lets the doctor compare areas of higher radioactivity on the PET scan with the more detailed appearance of that area on the CT scan. For people with SCLC, PET/CT scans are used more often than PET scans alone.

Bone scan

A bone scan can help show if a cancer has spread to the bones. This test is done mainly when there is reason to think the cancer may have spread to the bones (because of symptoms such as bone pain) and other test results aren’t clear.

For this test, you are injected with a slightly radioactive chemical that collects mainly in abnormal areas of bone. A special camera is then used to create a picture of areas of radioactivity in the body..

PET scans can also usually show if the cancer has spread to the bones, so you usually won’t need a bone scan if a PET scan has already been done.

Tests to diagnose lung cancer

Symptoms and the results of imaging tests might suggest that a person has lung cancer, but the actual diagnosis is made by looking at cells from your lung with a microscope.

The cells can be taken from lung secretions (sputum or phlegm), fluid removed from the area around the lung (thoracentesis), or from a suspicious area (biopsy). The choice of which test(s) to use depends on the situation.

Sputum cytology

For this test, a sample of sputum (mucus you cough up from the lungs) is looked at under a microscope to see if it has cancer cells. The best way to do this is to get early morning samples from you 3 days in a row. This test is more likely to help find cancers that start in the major airways of the lung, such as most small cell lung cancers and squamous cell lung cancers. It may not be as helpful for finding other types of lung cancer.

Thoracentesis

If fluid has built up around your lungs (called a pleural effusion), doctors can use thoracentesis to relieve symptoms and to see if it is caused by cancer spreading to the lining of the lungs (pleura). The buildup might also be caused by other conditions, such as heart failure or an infection.

For this procedure, the skin is numbed and a hollow needle is inserted between the ribs to drain the fluid. (In a similar test called pericardiocentesis, fluid is removed from within the sac around the heart.) A microscope is used to check the fluid for cancer cells. Chemical tests of the fluid are also sometimes useful in telling a malignant (cancerous) pleural effusion from one that is not.

If a malignant pleural effusion has been diagnosed, thoracentesis may be repeated to remove more fluid. Fluid buildup can keep the lungs from filling with air, so thoracentesis can help a person breathe better.

Needle biopsy

Doctors can often use a hollow needle to get a small sample from a suspicious area (mass).

- In a fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy, the doctor uses a syringe with a very thin, hollow needle to withdraw (aspirate) cells and small fragments of tissue.

- In a core biopsy, a larger needle is used to remove one or more small cores of tissue. Samples from core biopsies are larger than FNA biopsies, so they are often preferred.

An advantage of needle biopsies is that they don’t require a surgical incision, but in some cases they might not provide enough of a sample to make a diagnosis.

Transthoracic needle biopsy: If the suspected tumor is in the outer part of the lungs, the biopsy needle can be inserted through the skin on the chest wall. The area where the needle is to be inserted may be numbed with local anesthesia first. The doctor then guides the needle into the area while looking at the lungs with either fluoroscopy (which is like an x-ray, but the image is shown on a screen rather than on film) or CT scans. Unlike fluoroscopy, CT doesn’t give a constant picture, so the needle is inserted toward the mass, a CT image is taken, and the direction of the needle is guided based on the image. This is repeated a few times until the needle is within the mass.

A possible complication of this procedure is that air may leak out of the lung at the biopsy site and into the space between the lung and the chest wall. This is called a pneumothorax. It can cause part of the lung to collapse and could cause trouble breathing. If the air leak is small, it often gets better without any treatment. Larger air leaks are treated by putting a small tube into the chest space and sucking out the air over a day or two, after which it usually heals on its own.

Other approaches to needle biopsies: An FNA biopsy may also be done to check for cancer in the lymph nodes between the lungs:

- Transtracheal FNA or transbronchial FNA is done by passing the needle through the wall of the trachea (windpipe) or bronchi (the large airways leading into the lungs) during bronchoscopy or endobronchial ultrasound (described below).

- Some patients have an FNA biopsy done during endoscopic esophageal ultrasound (described below) by passing the needle through the wall of the esophagus.

Bronchoscopy

Bronchoscopy can help the doctor find some tumors or blockages in the larger airways of the lungs. It may be used to find a lung tumor or to take a sample of a tumor to see if it is cancer.

For this exam, a lighted, flexible fiber-optic tube (called a bronchoscope) is passed through the mouth or nose and down into the windpipe and bronchi. The mouth and throat are sprayed first with a numbing medicine. You may also be given medicine through an intravenous (IV) line to make you feel relaxed.

Small instruments can be passed down the bronchoscope to take biopsy samples. The doctor can also sample cells that line the airways by using a small brush (bronchial brushing) or by rinsing the airways with sterile saltwater (bronchial washing). These tissue and cell samples are then looked at under a microscope.

Tests to find lung cancer spread

If lung cancer has been found, it’s often important to know if it has spread to the lymph nodes in the space between the lungs (mediastinum) or other nearby areas. This can affect a person’s treatment options.

Several types of tests might be done to look for cancer spread if surgery could be an option for treatment, but this is not often the case for small cell lung cancer. These tests are used more often for non-small cell lung cancer.

Endobronchial ultrasound

Ultrasound is a type of imaging test that uses sound waves to create pictures of the inside of your body. For this test, a small, microphone-like instrument called a transducer gives off sound waves and picks up the echoes as they bounce off body tissues. The echoes are converted by a computer into an image on a computer screen.

For endobronchial ultrasound, a bronchoscope is fitted with an ultrasound transducer at its tip and is passed down into the windpipe. This is done with numbing medicine (local anesthesia) and light sedation.

The transducer can be pointed in different directions to look at lymph nodes and other structures in the mediastinum (the area between the lungs). If suspicious areas such as enlarged lymph nodes are seen on the ultrasound, a hollow needle can be passed through the bronchoscope to get biopsy samples of them. The samples are then sent to a lab to be looked at with a microscope.

Endoscopic esophageal ultrasound

This test is like endobronchial ultrasound, except the doctor passes an endoscope (a lighted, flexible scope) down the throat and into the esophagus (the tube connecting the throat to the stomach). This is done with numbing medicine (local anesthesia) and light sedation.

The esophagus is just behind the windpipe and is close to some lymph nodes inside the chest to which lung cancer may spread. As with endobronchial ultrasound, the transducer can be pointed in different directions to look at lymph nodes and other structures inside the chest that might contain lung cancer. If enlarged lymph nodes are seen on the ultrasound, a hollow needle can be passed through the endoscope to get biopsy samples of them. The samples are then sent to a lab to be looked at under a microscope.

Mediastinoscopy and mediastinotomy

These procedures may be done to look more directly at and get samples from the structures in the mediastinum (the area between the lungs). They are done in an operating room by a surgeon while you are under general anesthesia (in a deep sleep). The main difference between the two is in the location and size of the incision.

Mediastinoscopy: A small cut is made in the front of the neck and a thin, hollow, lighted tube is inserted behind the sternum (breast bone) and in front of the windpipe to look at the area. Instruments can be passed through this tube to take tissue samples from the lymph nodes along the windpipe and the major bronchial tube areas. Looking at the samples under a microscope can show if they contain cancer cells.

Mediastinotomy: The surgeon makes a slightly larger incision (usually about 2 inches long) between the second and third ribs next to the breast bone. This lets the surgeon reach some lymph nodes that cannot be reached by mediastinoscopy.

Thoracoscopy

This procedure can be done to find out if cancer has spread to the spaces between the lungs and the chest wall, or to the linings of these spaces (called pleura). It can also be used to sample tumors on the outer parts of the lungs as well as nearby lymph nodes and fluid, and to assess whether a tumor is growing into nearby tissues or organs. This procedure is not often done just to diagnose lung cancer, unless other tests such as needle biopsies are unable to get enough samples for the diagnosis.

Thoracoscopy is done in an operating room while you are under general anesthesia (in a deep sleep). A small cut (incision) is made in the side of the chest wall. (Sometimes more than one cut is made.) The doctor then puts a thin, lighted tube with a small video camera on the end through the incision to view the space between the lungs and the chest wall. Using this, the doctor can see possible cancer deposits on the lining of the lung or chest wall and remove small pieces of the tissue to be looked at under the microscope. (When certain areas can’t be reached with thoracoscopy, the surgeon may need to make a larger incision in the chest wall, known as a thoracotomy.)

Thoracoscopy can also be used as part of the treatment to remove part of a lung in some early-stage lung cancers. This type of operation, known as video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS), is described in more detail in Surgery for Small Cell Lung Cancer.

Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy

These tests look for spread of the cancer into the bone marrow. Bone marrow is the soft, inner part of certain bones where new blood cells are made.

The two tests are usually done at the same time. The samples are most often taken from the back of the pelvic (hip) bone.

In bone marrow aspiration, you lie on a table (either on your side or on your belly). The skin over the hip is cleaned. Then the skin and the surface of the bone are numbed with local anesthetic, which may cause a brief stinging or burning sensation. A thin, hollow needle is then inserted into the bone, and a syringe is used to suck out a small amount of liquid bone marrow. Even with the anesthetic, most people still have some brief pain when the marrow is removed.

A bone marrow biopsy is usually done just after the aspiration. A small piece of bone and marrow is removed with a slightly larger needle that is pushed down into the bone. The biopsy will likely also cause some brief pain.

Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy are sometimes done in patients thought to have early (limited) stage SCLC but who have blood test results suggesting the cancer might have reached the bone marrow. In recent years, PET scans have been used more often for staging, so these tests are now rarely done for SCLC.

Lab tests of biopsy and other samples

Samples that have been collected during biopsies or other tests are sent to a pathology lab. A pathologist, a doctor who uses lab tests to diagnose diseases such as cancer, will look at the samples under a microscope and may do other special tests to help better classify the cancer. Cancers from other organs can spread to the lungs. It’s very important to find out where the cancer started, because treatment is different depending on the type of cancer.

The results of these tests are described in a pathology report, which is usually available within about a week. If you have any questions about your pathology results or any diagnostic tests, talk to your doctor.

Blood tests

Blood tests are not used to diagnose lung cancer, but they can help to get a sense of a person’s overall health. For example, they can be used to help tell if a person is healthy enough to have surgery.

A complete blood count (CBC) determines whether your blood has normal numbers of different types of blood cells. For example, it can show if you are anemic (have a low number of red blood cells), if you could have trouble with bleeding (due to a low number of blood platelets), or if you are at increased risk for infections (due to a low number of white blood cells). This test will be repeated regularly if you are treated with chemotherapy, because these drugs can affect blood-forming cells of the bone marrow.

Blood chemistry tests can help spot abnormalities in some of your organs, such as the liver or kidneys. For example, if cancer has spread to the bones, it may cause higher than normal levels of calcium and alkaline phosphatase.

Lung function tests

Lung (or pulmonary) function tests (PFTs) may be done after lung cancer is diagnosed to see how well your lungs are working. They are generally only needed if surgery might be an option in treating the cancer, which is rare in small cell lung cancer. Surgery to remove lung cancer requires removing part or all of a lung, so it’s important to know how well the lungs are working beforehand.

There are different types of PFTs, but they all basically have you breathe in and out through a tube that is connected to a machine that measures airflow.

Small Cell Lung Cancer Stages

The stage of a cancer describes how far it has spread. The stage is one of the most important factors in deciding how to treat the cancer and determining how successful treatment might be.

For treatment purposes, most doctors use a 2-stage system that divides SCLC into limited stage and extensive stage. For limited stage cancer, a person might benefit from more aggressive treatments such as chemotherapy combined with radiation therapy to try to cure the cancer. For extensive stage disease, chemotherapy alone is likely to be a better option to control (not cure) the cancer.

Limited stage and extensive stage

For treatment purposes, most doctors use a 2-stage system that divides small cell lung cancer into limited stage and extensive stage 55. This helps determine if a person might benefit from more aggressive treatments such as chemotherapy combined with radiation therapy to try to cure the cancer (for limited stage cancer), or whether chemotherapy alone is likely to be a better option (for extensive stage cancer).

Limited stage

This means that the cancer is only on one side of the chest and can be treated with a single radiation field. This generally includes cancers that are only in one lung (unless tumors are widespread throughout the lung), and that might have also reached the lymph nodes on the same side of the chest.

This generally means your cancer:

- is only in one lung (unless tumors are widespread throughout the lung)

- and that might also have reached the lymph nodes on the same side of the chest – for example, in the center of the chest or above the collar bone

Cancer in lymph nodes above the collarbone (called supraclavicular nodes) might still be considered limited stage as long as they are on the same side of the chest as the cancer. Some doctors also include lymph nodes at the center of the chest (mediastinal lymph nodes) even when they are closer to the other side of the chest.

What is important is that the cancer is confined to an area that is small enough to be treated with radiation therapy in one “port” or one treatment area. Only about 1 out of 3 people with small cell lung cancer have limited stage cancer when it is first found.

If you have limited disease you are likely to have chemotherapy as well as radiotherapy treatment. This is sometimes called chemoradiotherapy.

Some people also have surgery.

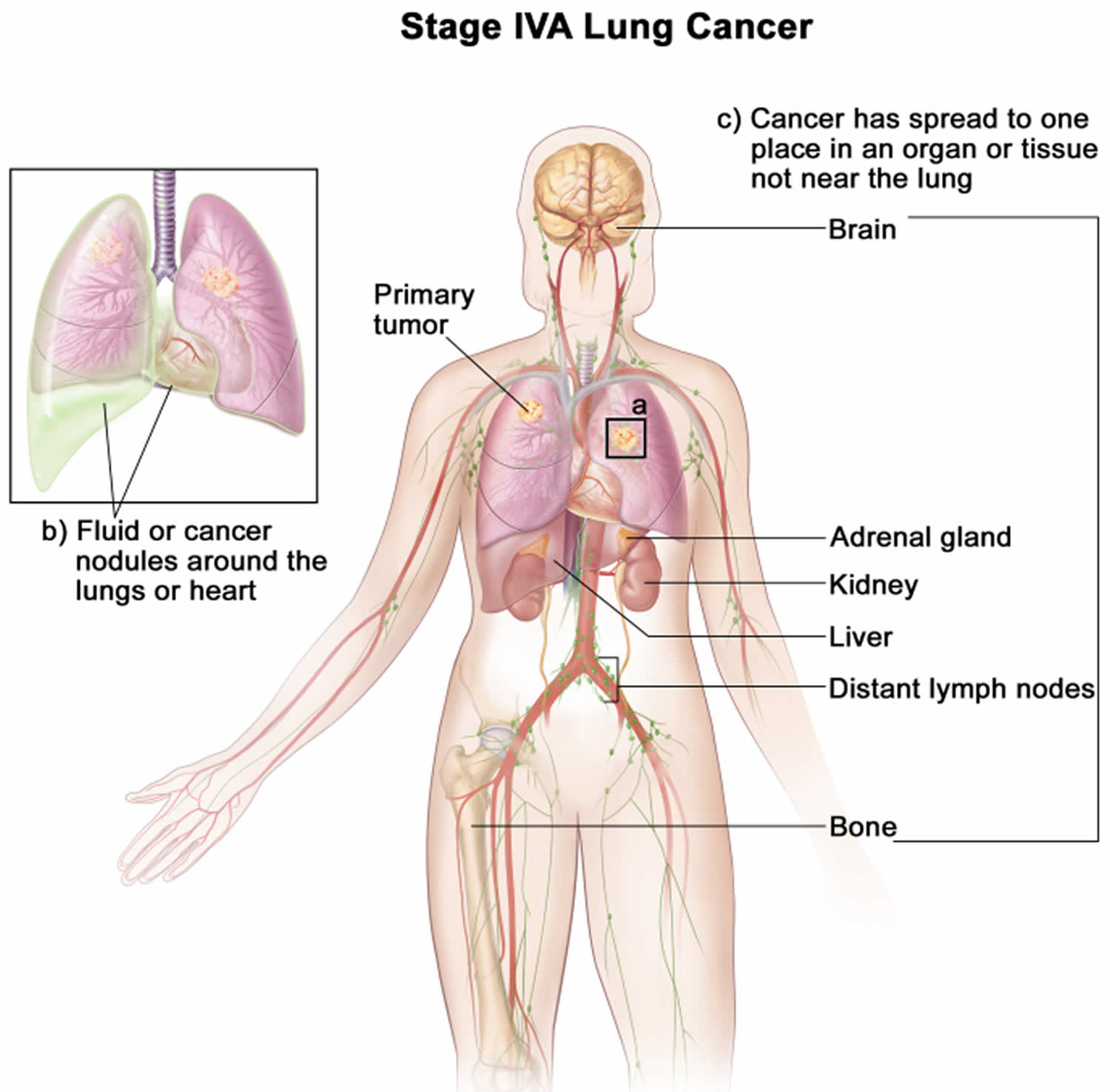

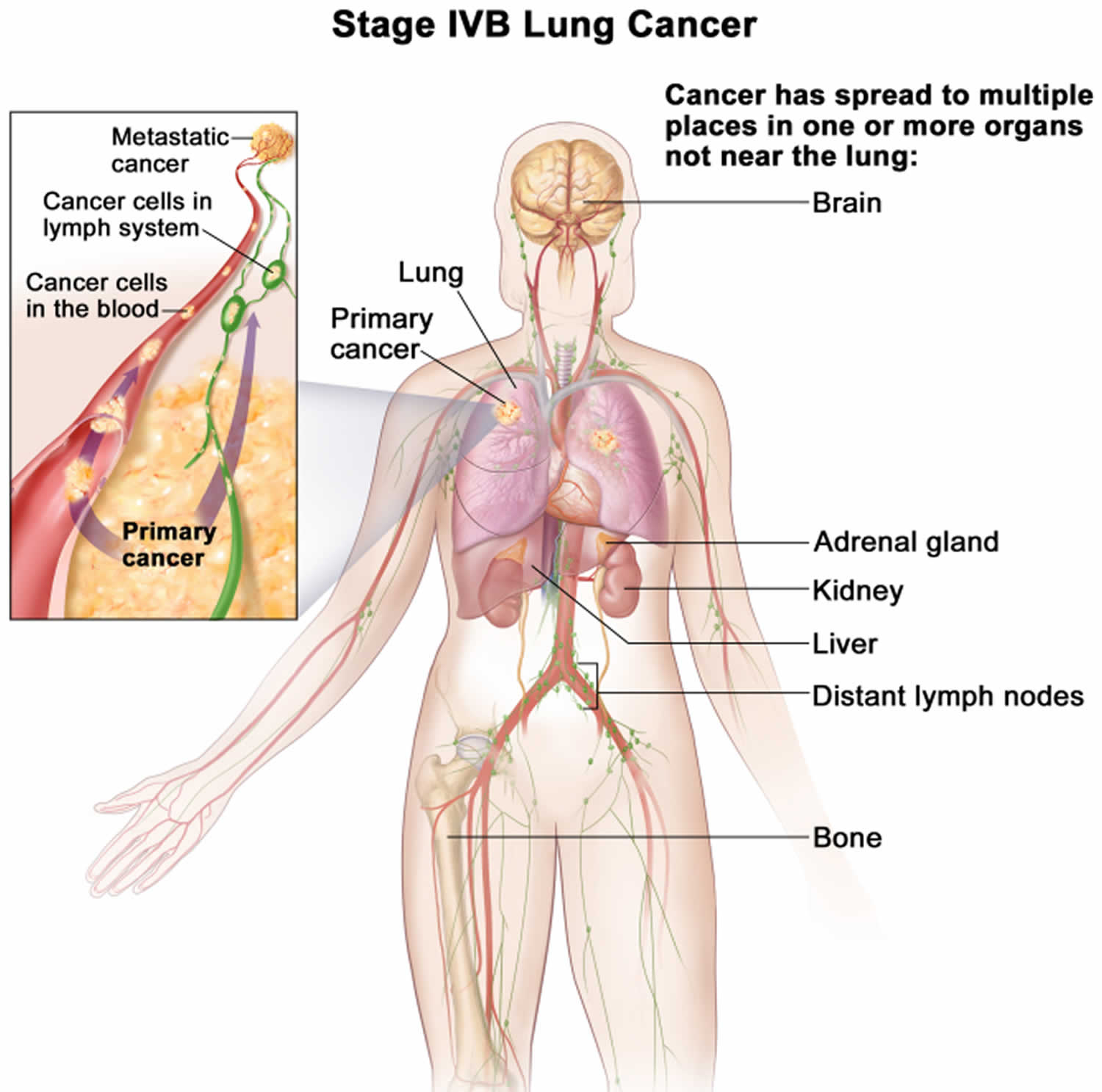

Extensive stage

Extensive disease means that the cancer has spread widely throughout the lung, to the other lung, to lymph nodes on the other side of the chest, or to other parts of the body (including the bone marrow). Many doctors consider small cell lung cancer that has spread to the fluid around the lung (a malignant pleural effusion) to be extensive stage as well. About 2 out of 3 people with small cell lung cancer have extensive disease when their cancer is first found.

Extensive disease small cell lung cancer might have spread:

- within the chest (either to the other lung or to lymph nodes further away from the cancer)

- or to other parts of your body

Or there may be cancer cells in the fluid around the lung (a malignant pleural effusion).

The main treatment for extensive stage disease is chemotherapy.

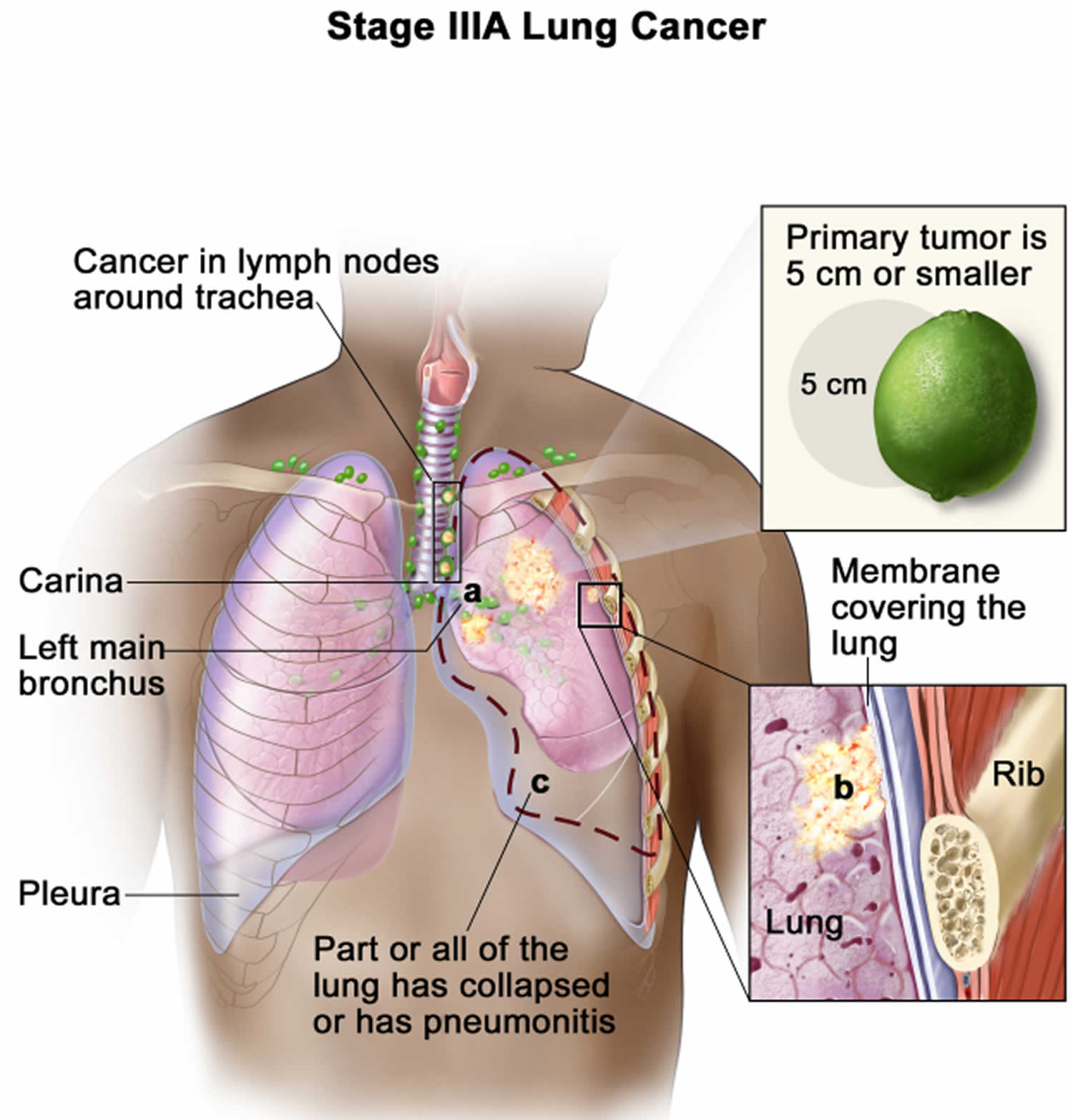

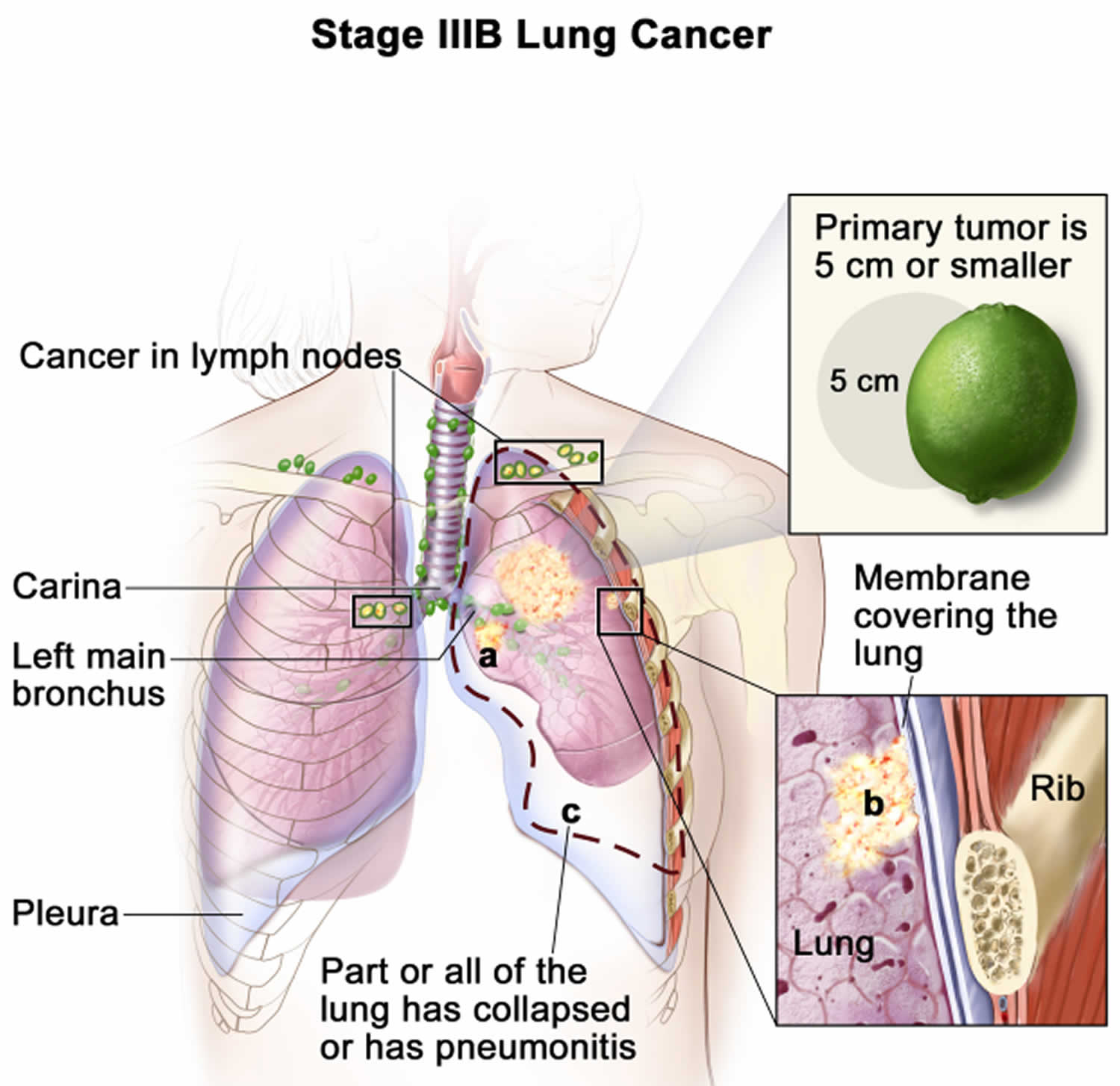

The TNM staging system

A more formal system to describe the growth and spread of lung cancer is the American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM staging system, which is based on:

- The size of the main (primary) tumor (T) and whether it has grown into nearby areas.

- Whether the cancer has spread to nearby (regional) lymph nodes (N). Lymph nodes are small bean-shaped collections of immune cells to which cancers often spread before going to other parts of the body.

- Whether the cancer has spread (metastasized) (M) to other organs of the body. (The most common sites are the brain, bones, adrenal glands, liver, kidneys, and the other lung.)

Numbers or letters appear after T, N, and M to provide more details about each of these factors. Higher numbers mean the cancer is more advanced. Once the T, N, and M categories have been determined, this information is combined in a process called stage grouping, to assign an overall stage.

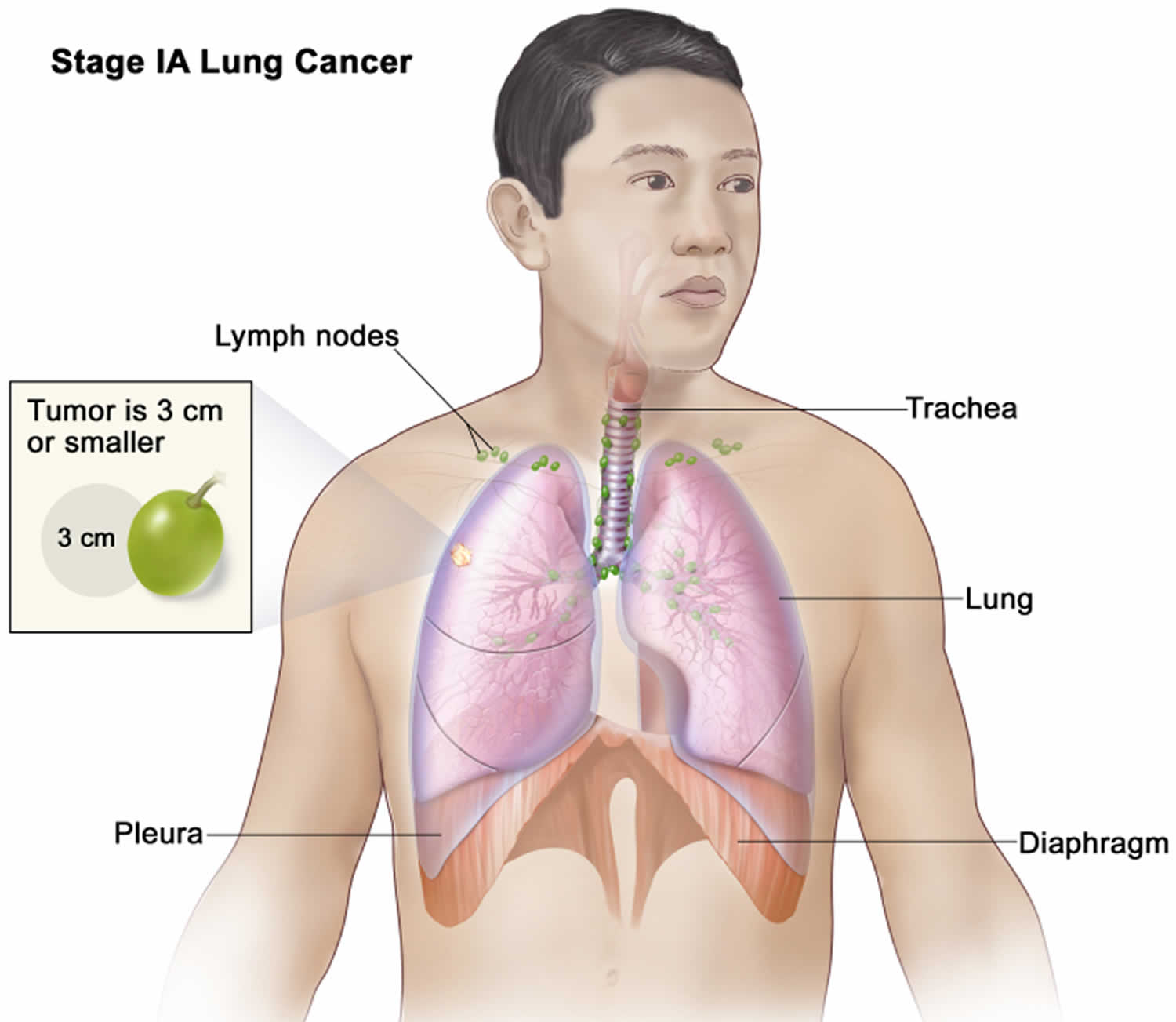

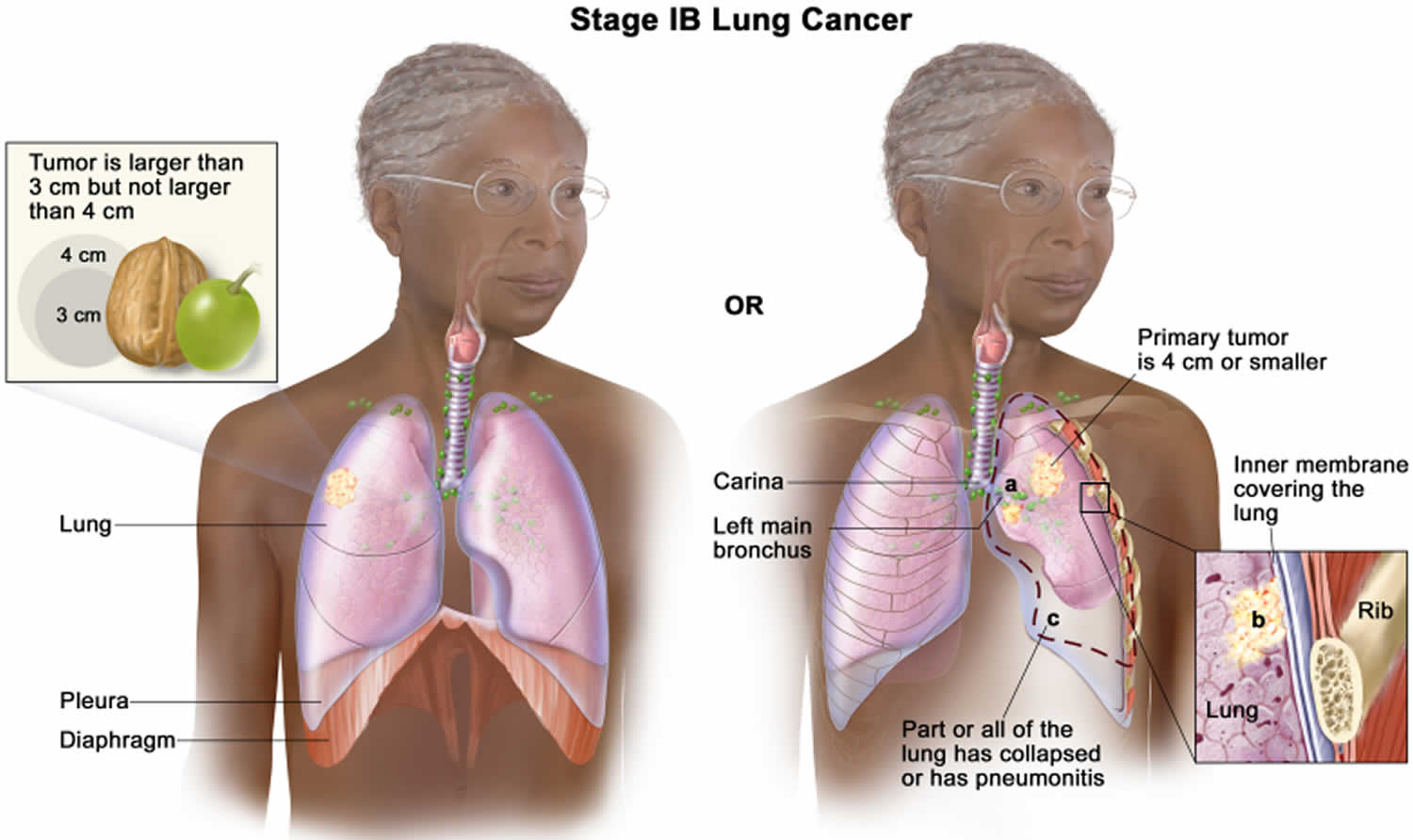

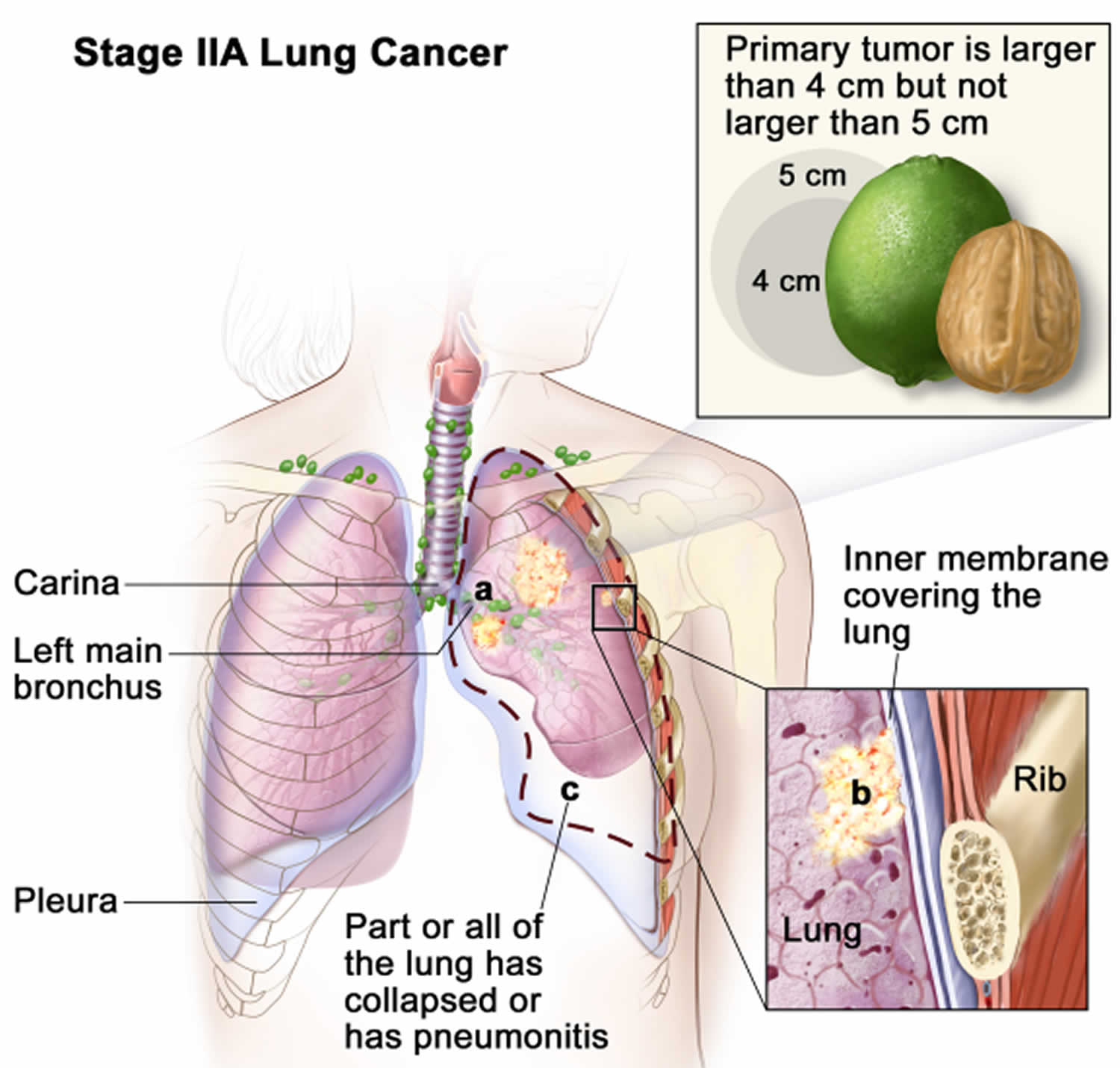

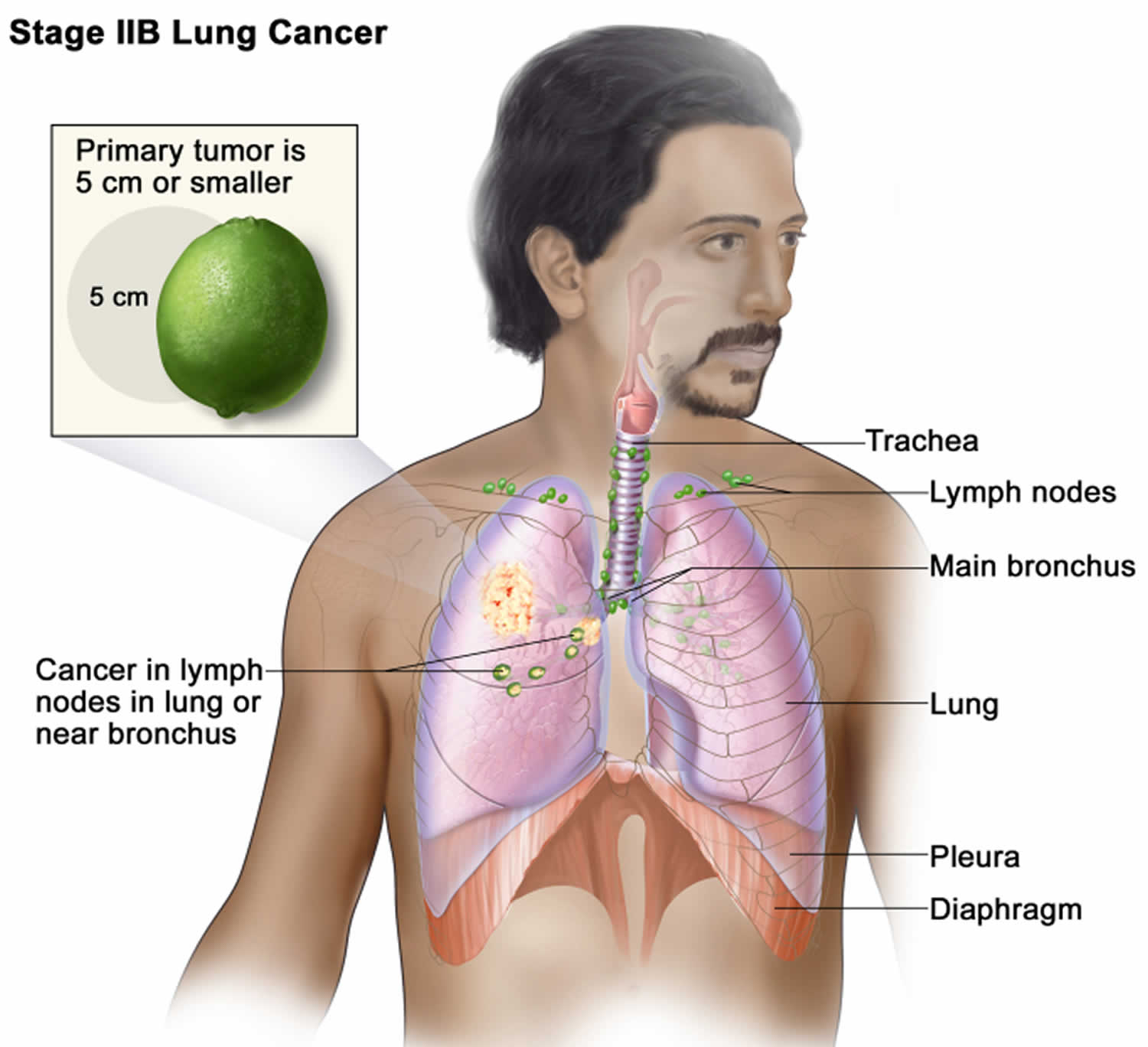

Details of the TNM staging system

The TNM staging system is complex and can be hard for patients (and even some doctors) to understand. If you have any questions about the stage of your cancer, ask your doctor to explain it to you.

T categories for lung cancer

- TX: The main (primary) tumor can’t be assessed, or cancer cells were seen on sputum cytology or bronchial washing but no tumor can be found.

- T0: There is no evidence of a primary tumor.

- Tis: Cancer is found only in the top layers of cells lining the air passages. It has not grown into deeper lung tissues. This is also known as carcinoma in situ.

- T1: The tumor is no larger than 3 centimeters (cm)—slightly less than 1¼ inches—across, has not reached the membranes that surround the lungs (visceral pleura), and does not affect the main branches of the bronchi.