Testosterone

Testosterone is the major male sex hormone and is produced by the male testes in men and to a lesser extent by the adrenal glands in both men and women. In men, testosterone is thought to regulate sex drive (libido), bone mass, fat distribution, promotes gains in muscle mass and strength when combined with resistance training, the production of red blood cells and controlling fertility and the development of sperm (spermatogenesis) 1. Testosterone also plays an important part in the development of ‘male sex characteristics’ such as a deeper voice and certain patterns of muscle development and hair growth. Testosterone helps bring on the physical changes that turn a boy into a man. This time of life is called puberty. Adolescent boys with too little testosterone may not experience normal masculinization. For example, the genitals may not enlarge, facial and body hair may be scant and the voice may not deepen normally. In women or anyone with ovaries, testosterone impacts overall growth as well as development of muscle and reproductive tissue. Testosterone is produced in the Leydig cells in the testis in men and to a lesser extent by the adrenal glands in both men and women 2. In males, the normal range for early morning testosterone is between 300 ng/dL to 1000 ng/dL but may vary from laboratory to laboratory 3, 4, 5. Low testosterone levels in men is defined as total testosterone < 350 ng/dL and free testosterone < 225 pmol/L are associated with sexual dysfunction such as low sexual desire (low libido), erectile dysfunction (fewer or diminished spontaneous erections, decreased nocturnal penile tumescence), reduced skeletal muscle mass and strength, decreased bone mineral density, sparse beard growth, shrinking testes, increased cardiovascular risk and alterations of the glycometabolic profile 6, 3, 7, 8, 9. Testosterone is used only for men with low testosterone levels caused by certain medical conditions, including disorders of the testicles, pituitary gland (a small gland in the brain), or hypothalamus (a part of the brain) that cause male hypogonadism (a condition in which the body does not produce enough natural testosterone) 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18. Your doctor will order certain lab tests to check your testosterone levels to see if they are low before you begin to take testosterone.

Testosterone should not be used treat the symptoms of low testosterone in men who have low testosterone due to aging also called ‘age-related hypogonadism‘ or ‘late-onset hypogonadism‘ 19, 20, 21. Testosterone production and testicular function tend to decrease in aging men by 1% to 2% per year after the fifth decade 22, 23. Similarly, testicular volume decreases about 15% from age 25 to 90 years, impacting on quantity and quality of sperm 24, 25, 26. Hypogonadism occurs in 19% of men in their 60s, 28% of men in their 70s, and 49% of men in their 80s 27. Testosterone deficiency is very common in elderly men and is linked to different signs and symptoms such as reduced libido, reduced sexual functioning, decreases in mobility and energy that could heavily affect the aging process and the quality of life 28, 29, 30.

Unmodified testosterone is not orally available, so it must be given intramuscularly (e.g., testosterone cypionate [Depo-Testosterone], testosterone enanthate (Xyosted, available generically), testosterone undecanoate (Aveed), and testosterone pellet (Testopel) are forms of testosterone injection used to treat symptoms of low testosterone in men who have hypogonadism), sublingually (e.g., testosterone buccal), intranasally (e.g., testosterone nasal gel) or by transcutaneous patch (e.g., testosterone transdermal patch) 31.

A small amount of circulating testosterone is converted to estradiol (E2), a form of estrogen. As men age, they often make less testosterone, and so they produce less estradiol as well. Thus, changes often attributed to testosterone deficiency might be partly or entirely due to the accompanying decline in estradiol.

Testosterone is now widely prescribed to men whose bodies naturally produce low levels. But the levels at which testosterone deficiency become medically relevant still aren’t well understood. Normal testosterone production varies widely in men, so it’s difficult to know what levels have medical significance. Testosterone hormone’s mechanisms of action are also unclear.

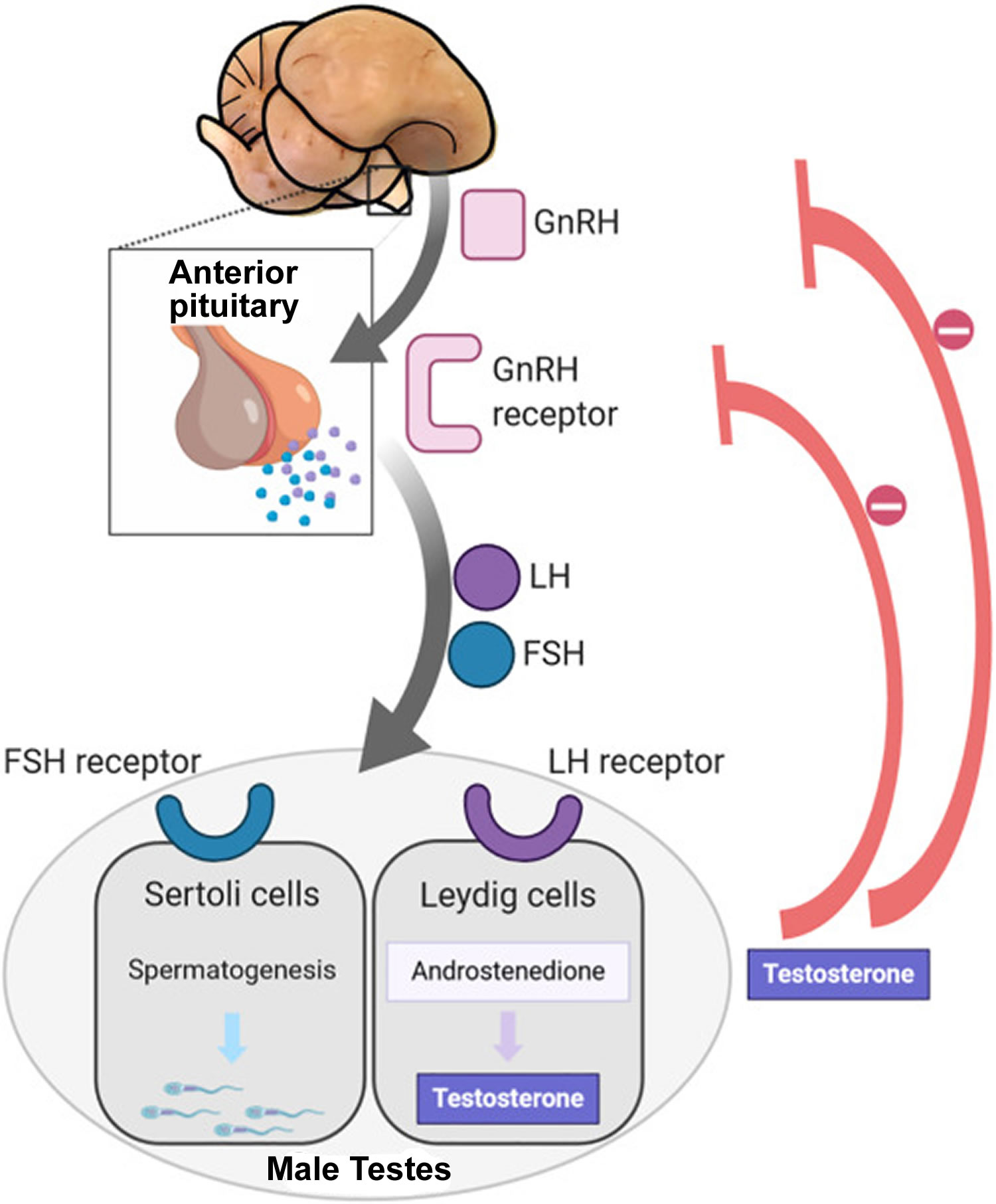

The amount of testosterone synthesized is regulated by the hypothalamic–pituitary–testicular axis (Figure 1) 32. The brain and pituitary gland, a small gland at the base of the brain, control production of testosterone by the testes. In males, testosterone is synthesized primarily in the testes (testicles) by the Leydig cells. The number of Leydig cells in turn is regulated by luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). In addition, the amount of testosterone produced by existing Leydig cells is under the control of LH, which regulates the expression of 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 33. When testosterone levels are low, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) is released by the hypothalamus, which in turn stimulates the pituitary gland to release FSH (follicle-stimulating hormone) and LH (luteinizing hormone). These latter two hormones stimulate the testis to synthesize testosterone. Finally, increasing levels of testosterone through a negative feedback loop act on the hypothalamus and pituitary to inhibit the release of GnRH and FSH/LH, respectively (Figure 1).

Prior to puberty, there is no sex difference in circulating testosterone concentrations or athletic performance, but from puberty onward a clear sex difference in athletic performance emerges as circulating testosterone concentrations rise in men because testes (testicles) produce 30 times more testosterone than before puberty with circulating testosterone exceeding 15-fold that of women at any age 34. There is a wide sex difference in circulating testosterone concentrations and a reproducible dose-response relationship between circulating testosterone and muscle mass and strength as well as circulating hemoglobin in both men and women. These dichotomies largely account for the sex differences in muscle mass and strength and circulating hemoglobin levels that result in at least an 8% to 12% performance-enhancing advantage in men.

Testosterone is the major sex hormone in males and testosterone makes a man look and feel like a man. In a man, testosterone hormone helps 35:

- The development of the penis and testes (testicles)

- The deepening of the voice during puberty

- The appearance of facial and pubic hair starting at puberty; later in life, it may play a role in balding (androgenic alopecia)

- Promote gains in muscle mass and strength when combined with resistance training 36.

- Bone growth and strength

- Growth spurts in puberty

- Sex drive (libido) and erections

- Sperm production (spermatogenesis)

- Fat distribution

- Make red blood cells

- Maintain normal mood and boost energy

There may be other important functions of testosterone hormone that have not yet been discovered.

Testosterone in the blood can be either bound or free:

- Bound testosterone is attached to proteins such as sex-hormone-binding-globulin (SHBG) and albumin. Most testosterone (approximately 60–70%) is transported in the blood to target tissues bound to sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), which in men is also called testosterone-binding globulin. About 30–40% of testosterone is loosely bound to albumin. This majority supply of protein-bound testosterone acts as a surplus of testosterone hormone for the body 37.

- Free testosterone, the active form, is all the remaining testosterone that is not bound to other substances. The small amounts of free testosterone (approximately 0.5–2%) in the blood act at the level of the tissues, primarily the seminal vesicles, bone, muscle, and prostate gland 37.

Historically, only free testosterone was thought to be the biologically active component. However, testosterone is weakly bound to serum albumin and dissociates freely in the capillary bed, thereby becoming readily available for tissue uptake. All non-SHBG-bound testosterone is therefore considered bioavailable.

Decreased testosterone levels indicate partial or complete hypogonadism. Hypogonadism is a clinical syndrome (group of symptoms) that is characterized by low serum testosterone levels and the presence of symptoms including low libido, fatigue, fewer or diminished spontaneous erections, decreased nighttime penile tumescence, sparse beard growth, and shrinking testes 3, 38, 39, 40. The incidence of hypogonadism increases with age and affects approximately 4-5 million men in the United States 41.

Some men with low testosterone do not have any symptoms. Early symptoms (changes you feel) and signs (abnormalities that your doctor finds) of low testosterone in men include 42:

- A drop in sex drive. It’s normal to feel less interested in sex as you get older. But, it is not usually normal to have no interest in sex.

- Problems having an erection

- Low sperm count

- Enlarged or tender breasts

Later, low testosterone can lead to decreased muscle size and strength, bone loss, less energy, sleep problems such as insomnia, lower fertility, increase in body fat, depression and trouble concentrating. Some things can temporarily lower testosterone, for instance, too much exercise, poor nutrition, or serious illness. Living a healthy lifestyle with regular exercise and a good diet helps maintain normal testosterone levels.

Factors that may decrease production of testosterone can occur with:

- Aging: Testosterone levels gradually reduce as men age, by 1%–2% per year after the age of 30 -40 years 27, 43. This effect is sometimes referred to as andropause or late-onset hypogonadism (LOH) 44. However, on average serum levels of testosterone still remain within the normal range of young men 45. Furthermore, decreases in testosterone concentrations with age are gradual and vary between individuals, with higher rates of decline in men with adiposity and comorbid diseases 46. The age-dependent reference range for testosterone has not been defined and the criteria on cutoff levels for hypogonadism remain somewhat controversial 43.

- Exercise: Resistance training increases testosterone levels 47, however, in older men, that increase can be avoided by protein ingestion 48. Chronic stress from too much exercise (overtraining syndrome) and endurance training in men may lead to lower testosterone levels 49.

- Nutrients:

- Vitamin A deficiency may lead to sub-optimal plasma testosterone levels 50.

- Vitamin D supplementation might increase testosterone levels 51. However, results from preliminary randomized controlled trials are conflicting. Vitamin D treatment had no effect on testosterone levels in middle-aged healthy men with normal baseline testosterone 52. In male patients with advanced heart failure and low vitamin D, a daily vitamin D3 supplement of 4000 IU for 3 years did not prevent the decline in testosterone indices 53.

- Zinc deficiency lowers testosterone levels 54, but over-supplementation has no effect on serum testosterone 55.

- Diets: There is limited evidence that low-fat diets may reduce total and free testosterone levels in men 56 and moderate evidence that very high protein diets (≥35% protein) decrease total testosterone levels in men (∼5.23 nmol/L) 57.

- Weight loss: Reduction in weight may result in an increase in testosterone levels, as well as sex-hormone binding globulin (SHBG) 58, 59, 60. However, it’s unclear whether the improvement in semen quality is a result of the reduction in body weight per se or improved lifestyles remains unknown 58. Fat cells synthesize the enzyme aromatase, which converts testosterone, the male sex hormone, into estradiol, the female sex hormone. A 2021 meta-analysis indicated that overweight and/or obesity were associated with lower sperm quality (i.e., semen volume, sperm count and concentration, sperm vitality, total motility and normal morphology), and underweight was likewise associated with low sperm normal morphology 61. In conclusion, these results suggest that maintaining a healthy body weight is important for increasing sperm quality parameters and potentially male fertility.

- Too much body fat (obesity). Ask your doctor whether you need a test called free testosterone.

- Sleep: REM (rapid-eye movement) sleep increases nocturnal testosterone levels 62. Peak testosterone levels coincide with rapid-eye movement (REM) sleep onset. The decreasing sleep efficiency and numbers of REM sleep episodes with altered REM sleep latency observed in older men are associated with lower concentrations of circulating testosterone 62.

- Behavior: Dominance challenges can, in some cases, stimulate increased testosterone release in men 63.

- Antiandrogens: Natural or man-made antiandrogens including spearmint tea reduce testosterone levels 64. Licorice can decrease the production of testosterone and this effect is greater in females 65.

- Medicine side effects, such as from chemotherapy.

- Diseases of the testicles (trauma, cancer, infection, immune, iron overload and undescended testicle [cryptorchidism])

- Problems with glands in the brain (hypothalamus and pituitary) that control hormone production. The cause is either primary or secondary/tertiary (pituitary/hypothalamic) testicular failure.

- Primary testicular failure is associated with increased luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) levels, and decreased total, bioavailable, and free testosterone levels. Causes include:

- Genetic causes (eg, Klinefelter syndrome, XXY males)

- Developmental causes (eg, testicular maldescent)

- Testicular trauma or ischemia (eg, testicular torsion, surgical mishap during hernia operations)

- Infections (eg, mumps)

- Autoimmune diseases (eg, autoimmune polyglandular endocrine failure)

- Metabolic disorders (eg, hemochromatosis, liver failure)

- Orchidectomy

- Secondary/tertiary hypogonadism, also known as hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism, shows low testosterone and low, or inappropriately “normal,” LH/FSH levels; causes include:

- Inherited or developmental disorders of hypothalamus and pituitary (eg, Kallmann syndrome, congenital hypopituitarism)

- Pituitary or hypothalamic tumors

- Hyperprolactinemia of any cause

- Malnutrition or excessive exercise

- Cranial irradiation

- Head trauma

- Medical or recreational drugs (eg, estrogens, gonadotropin releasing hormone [GnRH] analogs, cannabis)

- Primary testicular failure is associated with increased luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) levels, and decreased total, bioavailable, and free testosterone levels. Causes include:

- Low thyroid function.

- Genetic disorders such as Klinefelter syndrome and Kallmann syndrome. Klinefelter syndrome is the most common congenital abnormality that results in primary hypogonadism. In Klinefelter syndrome, there is dysgenesis of seminiferous tubules and loss of Sertoli cells which leads to a decrease in inhibin levels and a resultant increase in follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). FSH upregulates aromatase leading to increased conversion of androgens to estrogens. In Klinefelter, there is also Leydig cell dysfunction which leads to decreased testosterone levels and an increase in luteinizing hormone (LH) due to loss of negative feedback. In Kallmann syndrome, failed migration of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH)-producing neurons leads to lack of GnRH (gonadotropin-releasing hormone). No GnRH results in a decrease in luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), testosterone, and sperm count. Specific to Kallmann syndrome, in comparison to other causes of hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, is defects in the sensation of smell (hyposmia or anosmia) 9.

- Other disorders, chronic diseases, treatments, or infection.

Increased total testosterone levels may be due to:

- Resistance to the action of male hormones (androgen resistance)

- Tumor of the ovaries

- Adrenal tumors

- Cancer of the testes

- Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH). In classic CAH (95% of cases), due to 21 hydroxylase deficiency, newborns usually present with ambiguous genitalia and later develop salt wasting, vomiting, hypotension, and acidosis. A marked increase in 17-hydroxyprogesterone is diverted towards adrenal androgen synthesis and leads to hyperandrogenism. Hyperandrogenism impairs hypothalamic sensitivity to progesterone leading to a rapid rise in GnRH synthesis and thus increased LH and FSH. Elevations in LH and FSH lead to increased gonadal steroid production (17-hydroxyprogesterone, dehydroepiandrosterone [DHEA], testosterone, LH, and FSH). Diagnosis is with adrenocorticotropic hormone stimulation test showing exaggerated 17 hydroxyprogesterone response 66.

- Taking medicines or drugs that increase testosterone level (including some supplements)

During childhood, excessive production of testosterone induces premature puberty (puberty too early before age 9) in boys and masculinization in girls 42. Some rare conditions, such as certain types of tumors, cause boys to make testosterone earlier than normal. Young boys also can have too much testosterone if they touch testosterone gel that an adult man is using for treatment.

In females, the ovaries produce most of the testosterone. The adrenal glands can also produce too much of other androgens that are converted to testosterone. In adult women, excess testosterone production results in varying degrees of virilization, including hirsutism, acne, oligo-amenorrhea, or infertility. Levels are most often checked to evaluate signs of higher testosterone levels, such as:

- Acne, oily skin

- Change in voice

- Decreased breast size

- Excess hair growth (dark, coarse hairs in the area of the moustache, beard, sideburns, chest, buttocks, inner thighs)

- Increased size of the clitoris

- Irregular or absent menstrual periods

- Male-pattern baldness or hair thinning.

Mild-to-moderate testosterone elevations are usually asymptomatic in males but can cause distressing symptoms in females. The exact causes for mild-to-moderate elevations in testosterone often remain obscure. Common causes of pronounced elevations of testosterone include genetic conditions (eg, congenital adrenal hyperplasia); adrenal, testicular, and ovarian tumors; polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) and abuse of testosterone or gonadotrophins by athletes. Testosterone-producing ovarian or adrenal neoplasms often produce total testosterone values greater than 200 ng/dL. High estrogen values also may be observed, and LH and FSH are low or “normal.” In polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), hirsutism, acne, menstrual disturbances, insulin resistance and, frequently, obesity, form part of this syndrome. Total testosterone levels may be normal or mildly elevated and, uncommonly, greater than 200 ng/dL.

Figure 1. Hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis

Footnotes: In puberty, the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis plays a major role in regulating testosterone levels and gonadal function. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) is secreted from the hypothalamus by GnRH-expressing neurons. The GnRH travels down the hypothalamohypophyseal portal system to the anterior pituitary, which secretes luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). LH and FSH are two gonadotropic hormones that travel through the blood and act on receptors in the gonads. The largest amounts of testosterone (>95%) are produced by the testes in men, while the adrenal glands account for most of the remainder. In the testes, testosterone is produced by the Leydig cells 67. The male testes also contain Sertoli cells, which require testosterone for spermatogenesis (sperm cell development). Luteinizing hormone (LH), in particular, acts on the Leydig cells to increase testosterone production. Testosterone limits its own secretion via negative feedback. High levels of testosterone in the blood feedback to the hypothalamus to suppress the secretion of GnRH and also feedback to the anterior pituitary, making it less responsive to GnRH stimuli 68. Throughout the reproductive life of males, the hypothalamus releases GnRH in pulses every 1 to 3 hours. Despite this pulsatile release, however, average plasma levels of FSH and LH remain fairly constant from the start of puberty, where levels spike, to the third decade of life, where levels peak and slowly begin to decline. Prior to puberty, testosterone levels are low, reflecting the low secretion of GnRH and gonadotropins. Changes in neuronal input to the hypothalamus and brain activity during puberty cause a dramatic rise in GnRH secretion.

Testosterone production

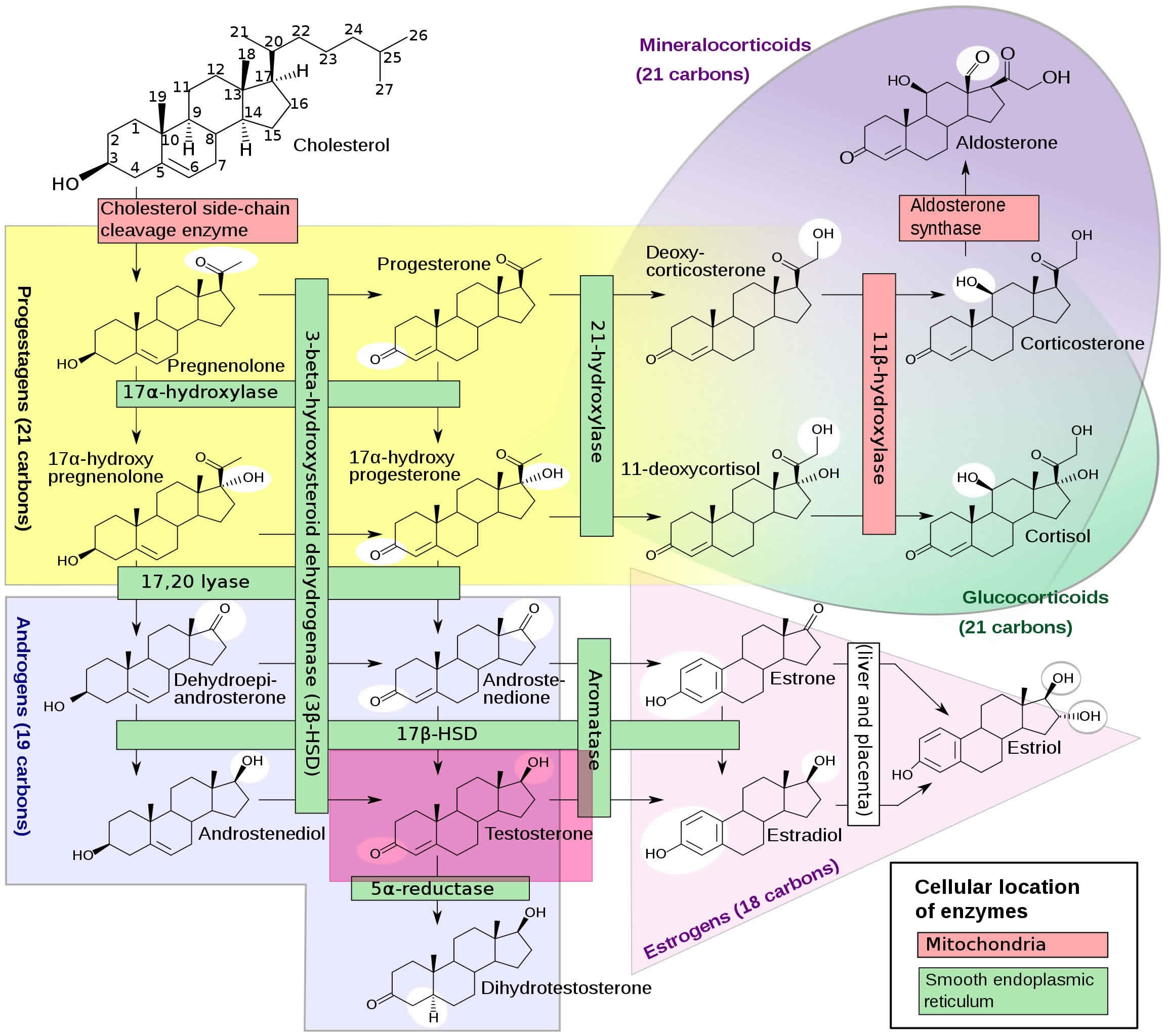

Testosterone is synthesized from cholesterol in the Leydig cells in the testis with further metabolism to dihydrotestosterone (DHT). The alternative or “backdoor” pathway shows dihydrotestosterone (DHT) production without going through testosterone. 5-alpha reductase is an enzyme that converts testosterone to dihydrotestosterone (DHT). Testosterone production in the fetal human testis starts during the 6th week of pregnancy. Leydig cell differentiation and the initial early testosterone biosynthesis in the fetal testis are independent of luteinizing hormone (LH) 69, 70, 71. During testis development production of testosterone comes under the control of luteinizing hormone (LH) which is produced by the pituitary gland. Synthesis and release of luteinizing hormone (LH) is under control of the hypothalamus through gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) and inhibited by testosterone via a negative feedback mechanism (Figure 1) 72. The biosynthetic conversion of cholesterol to testosterone involves several discrete steps, of which the first one includes the transfer of cholesterol from the outer to the inner mitochondrial membrane by the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (Star) and the subsequent side chain cleavage of cholesterol by the enzyme P450scc 73. This conversion, resulting in the synthesis of pregnenolone, is the rate-limiting step in testosterone biosynthesis. Subsequent steps require several enzymes including, 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, 17α-hydroxylase/C17-20-lyase and 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 3 (Figure 2) 74.

Metabolism of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone (DHT) occurs through the classical pathway (Figures 2 and 3) and is essential for initiation of the differentiation and development of the urogenital sinus into the prostate 2. Differentiation of male external genitalia (penis, scrotum and urethra) also strongly depends on the conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone (DHT) in the urogenital tubercle, labioscrotal swellings, and urogenital folds 75. In recent research there has been considerable interest in the alternative or ‘backdoor’ pathway of DHT production. This pathway has been found to have a significant role in the normal masculinization of the male fetus and abnormal virilization of the female fetus in cases of congenital adrenal hyperplasia resulting from mutations in the enzyme P450 oxidoreductase 76.

The irreversible conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone (DHT) is catalyzed by the microsomal enzyme 5-alpha reductase and is NADPH dependent 77. The cDNA of the gene for 5-alpha reductase codes for a protein of 254 amino acid residues with a predicted molecular mass of 28,398 Dalton 78, 79. Male patients with 5-alpha reductase deficiency present with normal female or male genitalia or ambiguous genitalia at birth due to lack of dihydrotestosterone (DHT). These patients have a male internal urogenital tract (anti-Mullerian hormone is still present). At puberty, adolescents with 5-alpha reductase deficiency, who may have been raised as girls due to lack of secondary male characteristics, begin to develop male secondary sex characteristics and have primary amenorrhea. These patients will have normal testosterone and LH, low dihydrotestosterone (DHT), and an increased testosterone-to-DHT ratio. In contrast to 5-alpha reductase deficiency, androgen insensitivity is a condition in which patients lack functional androgen receptors resulting in under-virilization. These patients, like those with 5-alpha reductase deficiency, have a 46 XY karyotype. In contrast, however, these patients have normal female external genitalia and usually undescended testes. In adolescence, they experience primary amenorrhea and breast development but have no pubic or axillary hair and lack the deepening voice changes that occur with puberty. They will have a blind vaginal pouch and abnormal internal reproductive organs (fallopian tubes, uterus, and the upper portion of the vagina) due to the production of the Mullerian inhibiting factor. These patients will have high levels of testosterone and LH 80.

Impaired testosterone metabolism can occur in certain cases of congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH). In classic CAH (95% of cases), due to 21 hydroxylase deficiency, newborns usually present with ambiguous genitalia and later develop salt wasting, vomiting, hypotension, and acidosis. A marked increase in 17-hydroxyprogesterone is diverted towards adrenal androgen synthesis and leads to hyperandrogenism. Hyperandrogenism impairs hypothalamic sensitivity to progesterone leading to a rapid rise in GnRH synthesis and thus increased LH and FSH. Elevations in LH and FSH lead to increased gonadal steroid production (17-hydroxyprogesterone, dehydroepiandrosterone [DHEA], testosterone, LH, and FSH). Diagnosis is with adrenocorticotropic hormone stimulation test showing exaggerated 17 hydroxyprogesterone response 66.

Figure 2. Testosterone biosynthetic pathways

Footnotes: Biosynthetic pathways for testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT) synthesis. The classic pathway show testosterone synthesized from cholesterol with further metabolism to dihydrotestosterone (DHT). The alternative or “backdoor” pathway shows DHT production without going through testosterone. Note only some of the enzymes are shown for clarity.

[Source 2 ]Figure 3. Enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of the adrenal steroid hormones and the gonadal steroid hormones

Footnotes: Figure 3 illustrates all of the enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of the adrenal steroid hormones, corticosterone, cortisol, and aldosterone; and the gonadal steroid hormones, progesterone, estradiol, and testosterone. Leydig cells in the testes function to turn cholesterol into testosterone 81. Luteinizing hormone (LH) regulates the initial step in this process. Two important intermediates in this process are dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and androstenedione. Androstenedione is converted to testosterone by the enzyme 17-beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase. At the cellular level, testosterone gets converted to dihydrotestosterone (DHT) by the enzyme 5-alpha-reductase. Dihydrotestosterone (DHT) is an androgen, which means it is a hormone that triggers the development of male characteristics 82. About 10% of the testosterone in the bodies of both men and women is converted into dihydrotestosterone (DHT) in adults, with a much higher amount in puberty. This may be why it is so closely related to the triggering of puberty. The dihydrotestosterone hormone (DHT) is much more powerful than testosterone. Dihydrotestosterone initiates the start of puberty in boys. It causes the genitals to develop and can cause the growth of pubic and body hair. It also causes the prostate to grow during puberty and may work together with testosterone to begin the expression of sexual desires and behavior. Women also have dihydrotestosterone (DHT), but its role in their bodies is not as well known. Some research has shown that it can lead to pubic hair growth after puberty in girls. It may also play a role in determining when puberty will start for a girl. Both men and women also produce weak acting androgens in the zona reticularis of the adrenal cortex. These weak-acting androgens are known as dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA and androstenedione. They bind to testosterone receptors with weaker affinity but can also be converted to testosterone in the peripheral tissues if produced at high amounts 82.

Testosterone function

Testosterone is the main male hormone that is responsible for regulating sex differentiation producing male sex characteristics with male primary sexual development, which includes testicular descent, spermatogenesis, enlargement of the penis and testes, and increasing libido 81. Testosterone’s effects are first seen in the fetus. During the first 6 weeks of development, the reproductive tissues of males and females are identical. At around week 7 in utero, the sex-related gene on the Y chromosome (SRY gene) initiates the development of the testicles. Sertoli cells from the testis cords (fetal testicles) eventually develop into seminiferous tubules. Sertoli cells produce a Mullerian-inhibiting substance (MIS), which leads to the regression of the Fallopian tubes, uterus, and upper segment of the vagina (Mullerian structures normally present in females). Fetal Leydig cells and endothelial cells migrate into the gonad and produce testosterone, which supports the differentiation of the Wolffian duct (mesonephric duct) structures that go on to become the male urogenital tract 81. Testosterone also gets converted to dihydrotestosterone (DHT) in the periphery and induces the formation of the prostate and male external genitalia. Testosterone is also responsible for testicular descent through the inguinal canal, which occurs in the last 2 months of fetal development. When an embryo lacks a Y chromosome and thus the SRY gene, ovaries develop. Fetal ovaries do not produce adequate amounts of testosterone, thus the Wolffian ducts do not develop. There is also an absence of Mullerian-inhibiting substance (MIS) in these individuals, leading to the development of the Mullerian ducts and female reproductive structures 83.

The testes usually begin the descent into the scrotum around 7 months of gestation, where the testes begin secreting reasonable quantities of testosterone. If a male child is born with undescended but normal testes that do not descend by 4 to 6 months of age, administration of testosterone can help the testes descend through the inguinal canals 84.

Testosterone is also involved in regulating secondary male characteristics, which are those responsible for masculinity. These secondary sex characteristics include male hair patterns, vocal changes, and voice deepening, anabolic effects, which include growth spurts in puberty (testosterone increases tissue growth at the epiphyseal plate early on and eventual closure of plate later in puberty) and skeletal muscle growth (testosterone stimulates protein synthesis). Testosterone also stimulates erythropoiesis, which results in a higher hematocrit in males versus females. Testosterone levels tend to drop with increasing age; because of this, men tend to experience a decrease in testicular size, a drop in libido, lower bone density, muscle mass decline, increased fat production, and decreased red blood cells production (erythropoiesis), which leads to possible anemia.

Normal testosterone levels

A total testosterone test measures both bound and free testosterone in a sample of blood. Total testosterone is the most commonly used test for diagnostic and monitoring purposes and levels are commonly reported in nanograms per deciliter of blood (ng/dL). Less often, a testosterone test may be performed for free testosterone, which is reported in picograms per deciliter of blood (pg/dL). Another less common test is for bioavailable testosterone, which is testosterone that can be used more readily by the body. Bioavailable testosterone includes all testosterone that is not bound to sex-hormone-binding-globulin (SHBG) , including free testosterone and albumin-bound testosterone. Bioavailable testosterone is also commonly reported in nanograms per deciliter of blood (ng/dL).

To measure your testosterone level, your doctor can order a blood test. The blood test should be done in the morning between 7:00 AM and 10:00 AM.

Normal testosterone levels

- Normal total testosterone levels in males: 300 to 1,000 nanograms per deciliter (ng/dL) or 10 to 35 nanomoles per liter (nmol/L). The harmonized normal serum total testosterone range in a healthy nonobese population of European and American men, 19 to 39 years, is 264 to 916 ng/dL 85. Furthermore, in randomized testosterone trials, the men with testosterone levels below the harmonized threshold would be more likely to respond to testosterone therapy than those with testosterone levels above the harmonized threshold.

- 0-5 months: 75-400 ng/dL

- 6 months-9 years: <7-20 ng/dL

- 10-11 years: <7-130 ng/dL

- 12-13 years: <7-800 ng/dL

- 14 years: <7-1,200 ng/dL

- 15-16 years: 100-1,200 ng/dL

- 17-18 years: 300-1,200 ng/dL

- Over 19 years: 240-950 ng/dL

- Normal total testosterone levels in females: 15 to 70 ng/dL or 0.5 to 2.4 nmol/L

- 0-5 months: 20-80 ng/dL

- 6 months to 9 years: <7-20 ng/dL

- 10-11 years: <7-44 ng/dL

- 12-16 years: <7-75 ng/dL

- 17-18 years: 20-75 ng/dL

- Over 19 years: 8-60 ng/dL

- Normal free testosterone levels in males:

- 20-25 years: 5.25-20.7 ng/dL

- 25-30 years: 5.05-19.8 ng/dL

- 30-35 years: 4.85-19.0 ng/dL

- 35-40 years: 4.65-18.1 ng/dL

- 40-45 years: 4.46-17.1 ng/dL

- 45-50 years: 4.26-16.4 ng/dL

- 50-55 years: 4.06-15.6 ng/dL

- 55-60 years: 3.87-14.7 ng/dL

- 60-65 years: 3.67-13.9 ng/dL

- 65-70 years: 3.47-13.0 ng/dL

- 70-75 years: 3.28-12.2 ng/dL

- 75-80 years: 3.08-11.3 ng/dL

- 80-85 years: 2.88-10.5 ng/dL

- 85-90 years: 2.69-9.61 ng/dL

- 90-95 years: 2.49-8.76 ng/dL

- 95-100+ years: 2.29-7.91 ng/dL

- Normal free testosterone levels in females:

- 20-25 years: 0.06-1.08 ng/dL

- 25-30 years: 0.06-1.06 ng/dL

- 30-35 years: 0.06-1.03 ng/dL

- 35-40 years: 0.06-1.00 ng/dL

- 40-45 years: 0.06-0.98 ng/dL

- 45-50 years: 0.06-0.95 ng/dL

- 50-55 years: 0.06-0.92 ng/dL

- 55-60 years: 0.06-0.90 ng/dL

- 60-65 years: 0.06-0.87 ng/dL

- 65-70 years: 0.06-0.84 ng/dL

- 70-75 years: 0.06-0.82 ng/dL

- 75-80 years: 0.06-0.79 ng/dL

- 80-85 years: 0.06-0.76 ng/dL

- 85-90 years: 0.06-0.73 ng/dL

- 90-95 years: 0.06-0.71 ng/dL

- 95-100+ years: 0.06-0.68 ng/dL

Talk to your doctor about the meaning of your specific test results. Testosterone levels change from hour to hour. Testosterone levels tend to be highest in the morning and lowest at night. Testosterone levels are highest by age 20 to 30 and slowly go down after age 30 to 35. In addition, normal testosterone level ranges may vary slightly among different laboratories. Some labs use different measurements or test different specimens.

If the result is not normal, you should repeat the test to make sure of the result. In healthy men, testosterone levels can change a lot from day to day, so a second test could be normal.

Low testosterone / testosterone deficiency

Testosterone deficiency also known as male hypogonadism, is defined as having one or more symptoms (e.g. decreased libido, decreased erections, decreased energy, decreased physical stamina, decreased lean muscle mass) attributable to low circulating levels of testosterone (morning serum total testosterone less than 300 ng/dL on two separate occasions) 12, 10, 86. An estimated 25% of men have low levels of testosterone 87. Besides being fundamental for the development and maintenance of male characteristics and male sexual organs, testosterone also has effects on most major organs, such as the brain, muscle, kidney, bone, liver and skin 88. Recent studies have also suggested that testosterone deficiency is independently and robustly associated with various obesity-related chronic diseases in men, including type 2 diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, hyperlipidemia, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) 89, 90. However, there is uncertainty as to what constitutes optimal physiological levels of total testosterone among men across different age categories, and to the effects that varying total testosterone levels have on disease risk 91. This debate is partially fueled by inconsistent findings in the literature and differences across expert clinical recommendations, as well as an incomplete understanding of the underlying mechanisms and temporal sequence of events leading to and stemming from testosterone deficiency. For example, the authors of a well-known systematic review 92 assert that although testosterone deficiency is robustly associated with obesity, insulin resistance, low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol and elevated triglycerides, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, and plasminogen activator type 1, there is insufficient evidence to demonstrate a causal role of endogenous testosterone deficiency on coronary artery disease-the leading cause of preventable death among men in the U.S 93.

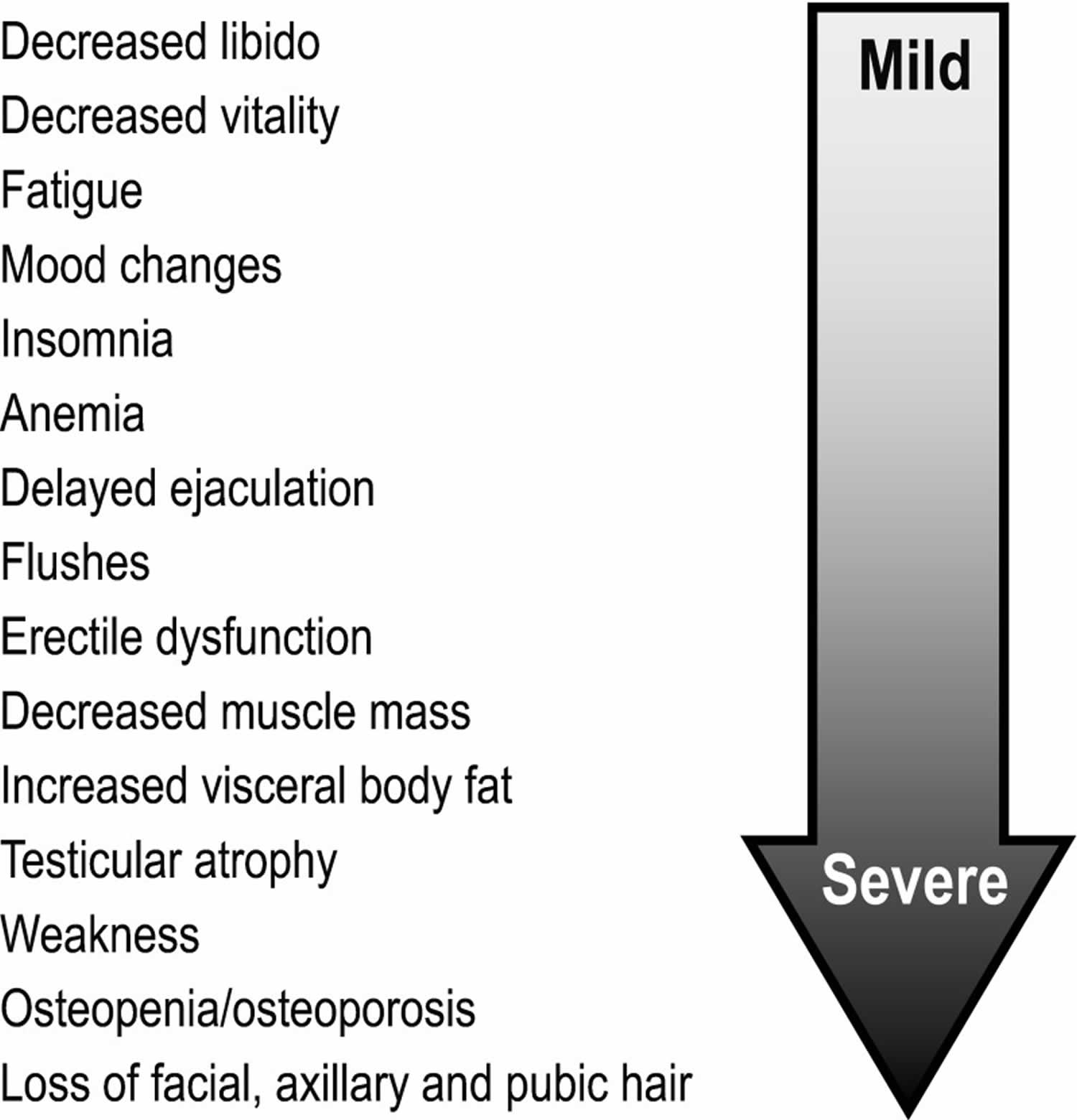

Incidence of hypogonadism (symptomatic low testosterone) increases with advancing male age such that levels of circulating testosterone decline annually by approximately 1% from the age of 40 years according to the European Male Ageing Study 46. When hypogonadism occurs in an older man, the condition is often called andropause or androgen deficiency of the aging male or late onset hypogonadism (LOH) 94. The most easily recognized clinical signs of late onset hypogonadism (andropause) in older men are a decrease in muscle mass and strength, a decrease in bone mass and osteoporosis, decreased libido, erectile dysfunction, anemia, increase in central body fat, and impaired memory, mood, concentration, and sleep 95, as well as increased mortality 96. Sexual symptoms and fatigue are the earliest and most common presentations 97. Other symptoms include depression, sleep alterations, poor concentration, and metabolic disorders are seen at borderline testosterone levels 98, 99. However, symptoms such as a decrease in libido and sexual desire, forgetfulness, loss of memory, anemia, difficulty in concentration, insomnia, and a decreased sense of well-being are more difficult to measure and differentiate from hormone-independent aging 100. Androgen deficiency of the aging male may result in significant detriment to quality of life and adversely affect the function of multiple organ systems 101.

The pathophysiology of male hypogonadism can be characterized into two types 102:

- Primary hypogonadism also known as primary testicular failure or hypergonadotropic hypogonadism. Primary hypogonadism is a testosterone deficiency due to a testicular abnormality impairing testosterone production; for example, Klinefelter syndrome, testicular tumors, infection, trauma, impaired Leydig cell function, or those caused by certain medications 103.

- Secondary hypogonadism also known as hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Secondary hypogonadism is a testosterone deficiency due to a problem in the hypothalamus or the pituitary gland, parts of the brain that signal the testicles to produce testosterone (i.e., luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)); for example, hypothalamic or pituitary lesions, GnRH deficiency, or hyperprolactinemia 103. Another important cause of hypogonadism is late-onset hypogonadism, an age-related (i.e., >40 years) decline in testosterone accompanied by clinical symptoms that is often associated with obesity, diabetes, and other chronic health conditions 104.

Risk factors for hypogonadism include:

- HIV/AIDS

- Previous chemotherapy or radiation therapy

- Aging

- Obesity

- Malnutrition

Late-onset hypogonadism (andropause) has the combined features of both primary and secondary hypogonadism 105. The diagnosis of andropause (late-onset hypogonadism) requires the presence of characteristic signs and symptoms, in combination with decreased serum total testosterone. Based on the recent guidelines by the International Society for the Study of Aging Male (ISSAM), the European Association of Urology (EAU), the European Society of Endocrinology (ESE), the European Academy of Andrology (EAA), and the American Association of Urology (AUA), a total testosterone of 250–350 ng/dL is the proper threshold value to define low testosterone. The optimal indication for TRT in late-onset hypogonadism (andropause) is the presence of signs and symptoms of hypogonadism, and low testosterone without contraindications for TRT 106.

Testosterone deficiency signs and symptoms

Testosterone deficiency signs and symptoms may include 106:

- Physical

- Anemia

- Reduced energy

Reduced endurance - Diminished work performance

- Diminished physical performance

- Fatigue

- Reduced lean muscle mass

- Obesity

- Loss of body hair

- Reduced beard growth

- Development of breast tissue (gynecomastia)

- Loss of bone mass (osteoporosis)

- Hot flashes

- Cognitive

- Depressive symptoms

- Cognitive dysfunction

- Reduced motivation

- Poor concentration

- Poor memory

- Irritability

- Sexual

- Reduced sex drive

- Reduced erectile function

Symptoms of hypogonadism may be categorized as sexual or non-sexual. Sexual symptoms include erectile dysfunction, diminished frequency of morning erections, and decrease in sexual thoughts (low libido), as well as difficulty in achieving orgasm and reduced intensity of orgasm 107. Non-sexual symptoms include fatigue, impotence, impaired concentration, depression, and decreased sense of vitality and/or well-being. Signs of hypogonadism also include anemia, osteopenia and osteoporosis, abdominal obesity, and metabolic syndrome 108.

Figure 4. Testosterone deficiency signs and symptoms

[Source 88 ]Testosterone deficiency causes

Testosterone deficiency also known as male hypogonadism, is defined as having one or more symptoms (e.g. decreased libido, decreased erections, decreased energy, decreased physical stamina, decreased lean muscle mass) attributable to low circulating levels of testosterone (morning serum total testosterone less than 300 ng/dL on two separate occasions) 12, 10, 86.

There are two basic types of hypogonadism:

- Primary. This type of hypogonadism — also known as primary testicular failure — originates from a problem in the testicles.

- Secondary. This type of hypogonadism indicates a problem in the hypothalamus or the pituitary gland — parts of the brain that signal the testicles to produce testosterone. The hypothalamus produces gonadotropin-releasing hormone, which signals the pituitary gland to make follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH). Luteinizing hormone then signals the testes to produce testosterone.

Either type of hypogonadism can be caused by an inherited (congenital) trait or something that happens later in life (acquired), such as an injury or an infection. At times, primary and secondary hypogonadism occur together.

Primary hypogonadism

Common causes of primary hypogonadism include:

- Klinefelter syndrome also known as 47,XXY or XXY male. Klinefelter syndrome results from a congenital abnormality of the sex chromosomes, X and Y. A male normally has one X and one Y chromosome. In Klinefelter syndrome, two or more X chromosomes are present in addition to one Y chromosome. The Y chromosome contains the genetic material that determines the sex of a child and related development. The extra X chromosome typically affects physical, neurodevelopmental, behavioral, and neurocognitive functioning. Common physical features may include tall stature, reduced muscle tone, abnormal development of the testicles (hypogonadism), which in turn results in underproduction of testosterone with delayed pubertal development and lack of secondary male sex characteristics such as decreased facial and body hair. Increased breast growth (gynecomastia) may occur later in puberty without appropriate biological care.

- Undescended testicles (cryptorchidism). Before birth, the testicles develop inside the abdomen and normally move down into their permanent place in the scrotum. Sometimes one or both of the testicles aren’t descended at birth. This condition often corrects itself within the first few years of life without treatment. If not corrected in early childhood, it can lead to malfunction of the testicles and reduced production of testosterone.

- Mumps orchitis. A mumps infection involving the testicles that occurs during adolescence or adulthood can damage the testicles, affecting the function of the testicles and testosterone production.

- Hemochromatosis. Too much iron in the blood can cause testicular failure or pituitary gland dysfunction, affecting testosterone production.

- Injury to the testicles. Because they’re outside the abdomen, the testicles are prone to injury. Damage to both testicles can cause hypogonadism. Damage to one testicle might not impair total testosterone production.

- Cancer treatment. Chemotherapy or radiation therapy for the treatment of cancer can interfere with testosterone and sperm production. The effects of both treatments often are temporary, but permanent infertility may occur. Although many men regain their fertility within a few months after treatment, preserving sperm before starting cancer therapy is an option for men.

Secondary hypogonadism

In secondary hypogonadism, the testicles are normal but don’t function properly due to a problem with the pituitary or hypothalamus. A number of conditions can cause secondary hypogonadism, including:

- Kallmann’s syndrome. This is an abnormal development of the area of the brain that controls the secretion of pituitary hormones (hypothalamus). This abnormality can also affect the ability to smell (anosmia) and cause red-green color blindness.

- Pituitary disorders. An abnormality in the pituitary gland can impair the release of hormones from the pituitary gland to the testicles, affecting normal testosterone production. A pituitary tumor or other type of brain tumor located near the pituitary gland may cause testosterone or other hormone deficiencies. Also, treatment for a brain tumor, such as surgery or radiation therapy, can affect the pituitary gland and cause hypogonadism.

- Inflammatory disease. Certain inflammatory diseases, such as sarcoidosis, histiocytosis and tuberculosis, involve the hypothalamus and pituitary gland and can affect testosterone production.

- HIV/AIDS. HIV/AIDS can cause low levels of testosterone by affecting the hypothalamus, the pituitary and the testes.

- Medications. The use of certain drugs, such as opiate pain medications and some hormones, can affect testosterone production.

- Obesity. Being significantly overweight at any age might be linked to hypogonadism.

- Aging. As men age, there’s a slow, progressive decrease in testosterone production. The rate varies greatly.

Low testosterone diagnosis

Your doctor will conduct a physical examination and note whether your sexual development, the amount and distribution of body hair (including beard growth and pubic hair), muscle mass and size and consistency of your testes, is consistent with your age. The prostate should be examined in older patients for size, consistency, symmetry, and presence of nodules or induration; it should be noted that the prostate may be enlarged in older men, despite a low testosterone level 109. Weight, height, body mass index (BMI), and waist circumference should also be measured, since signs and symptoms potentially indicative of testosterone deficiency in men include height loss, reduced muscle bulk and strength, and increased body fat, particularly increased BMI and abdominal fat accumulation 14.

Your doctor will test your blood level of testosterone if you have signs or symptoms of hypogonadism. Because testosterone levels vary and are generally highest in the morning, blood testing is usually done early in the day, before 10 a.m. (8 AM to 10 AM), possibly on more than one day. If both measurements are low, then certain studies should be ordered to rule out secondary hypogonadism. Further testing includes FSH (follicle-stimulating hormone), LH (luteinizing hormone), prolactin, TSH (thyroid-stimulating hormone), complete blood count (CBC), and comprehensive metabolic panel. In cases of low normal testosterone with clinical symptoms, further testing to assess free or bioavailable testosterone should be done. These tests include sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) and albumin to calculate the bioavailable testosterone which can be affected by obesity, type 2 diabetes, hypothyroidism, and liver disease. Furthermore, semen analysis, pituitary MRI, testicular ultrasound and biopsy, and genetic studies can be ordered, if there is clinical suspicion of a secondary cause.

Testosterone in blood is mainly bound to serum proteins with only 2% of the hormone circulating as free testosterone. Sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) accounts for 60-70% of testosterone binding, and 30-40% of the total testosterone is bound by albumin or other proteins. Bioavailable testosterone, referring to free and albumin-bound testosterone together, is thought to reflect an individual’s biologically active, circulating testosterone 110. Biochemical parameters commonly used to assess androgen deficiency include total testosterone (TT), free testosterone, calculated free testosterone, bioavailable testosterone (bT), and free androgen index 111. Theoretically, bioavailable testosterone (bT) is the most accurate; however, a standard method to measure bioavailable testosterone (bT) has not been established 110. Practically, morning total testosterone is the most widely accepted parameter, but results have been found to be misleading when sex-hormone-binding-globulin (SHBG) is elevated. The diagnosis of low testosterone should be made only after two total testosterone measurements have been taken on separate occasions between 8 and 11 AM due to the circadian rhythm of testosterone production by the testicles 110. Free testosterone measurement is recommended when total testosterone measurement is not diagnostic. In individuals with clinically suspected testosterone deficiency, sex-hormone-binding-globulin (SHBG) levels should be assessed if total testosterone is low to normal or borderline, especially in obese or older men 112. Calculation of free testosterone based on serum levels of testosterone and SHBG may be used to avoid inaccuracies in assessing the individual degree of androgenicity in a cost-effective manner 113. Since normal total testosterone ranges vary significantly between laboratories depending on the methods used and/or the assay kits employed, it is better to measure testosterone in the same laboratory 114.

Recently, other hormones are also being measured as per recommendations. In patients with low testosterone, serum luteinizing hormone (LH) should be measured to establish the cause of testosterone deficiency and may be an important factor in determining if adjunctive tests should be ordered 102. Serum prolactin levels should be measured in patients with low testosterone levels combined with low or low/normal LH levels to screen for hyperprolactinemia. Persistently elevated prolactin levels can indicate the presence of pituitary tumors, such as prolactinomas 115. Men with total testosterone levels <150 ng/dL in combination with a low or low/normal LH should undergo a pituitary MRI regardless of prolactin levels, as this may indicate non-secreting adenomas 116.

Table 1. Cutoff values of testosterone for low testosterone (testosterone deficiency) diagnosis

| Cutoff Values | Year of Release and Update | |

|---|---|---|

| Expert opinion | Total testosterone or free testosterone below the lower limits of normal | Before Official Guideline |

| International Society for the Study of the Aging Male (ISSAM) | Total testosterone < 231 ng/dL (8 nmol/L) Total testosterone: 231–346 ng/dL (8–12 nmol/L) or free testosterone < 52 pg/mL | 2005 |

| Total testosterone < 230 ng/dL (8 nmol/L) total testosterone: 230–350 ng/dL (8–12 nmol/L) or free testosterone < 52 pg/mL, sex-hormone-binding-globulin (SHBG) | 2008 | |

| Total testosterone < 350 ng/dL (12 nmol/L) or free testosterone < 65 pg/mL | 2015 | |

| Endocrine Society | Total testosterone < 300 ng/dL or free testosterone < 5 ng/dL | 2006 |

| Total testosterone < 280–300 ng/dL or free testosterone < 5–9 ng/dL | 2010 | |

| Total testosterone < 300 ng/dL or free testosterone < 5 ng/dL | 2018 | |

| International Society for Sexual Medicine (ISSM) | Total testosterone < 350 ng/dL (12 nmol/L) | International Consultation for Sexual Medicine (ICSM) 2015 |

| American Urological Association (AUA) | Total testosterone < 300 ng/dL | 2018 |

Low testosterone treatment

If you have low testosterone, man-made testosterone may help. This treatment is called testosterone replacement therapy or TRT. Testosterone replacement therapy can be given as a pill, gel, patch, injection, or implant.

TRT may relieve or improve symptoms in some men. It may help keep bones and muscles strong. Testosterone replacement therapy seems to be more effective in young men with very low testosterone levels. TRT can also be helpful for older men. Testosterone replacement therapy is FDA-approved as replacement therapy only for men who have low testosterone levels due to disorders of the testicles, pituitary gland, or brain that cause a condition called hypogonadism. Examples of these disorders include failure of the testicles to produce testosterone because of genetic problems, or damage from chemotherapy or infection 117, 118.

Testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) has risks. These may include 119:

- Infertility

- Enlarged prostate leading to difficulty urinating

- Blood clots 120

- Erythrocytosis or polycythemia (increased production of red blood cells) 121, 122

- Heart attacks

- Worsening heart failure

- Obstructive sleep apnea

- Cholesterol problems

At this time, it is unclear whether testosterone replacement therapy increases the risk of heart attack, stroke, or prostate cancer 119, 123.

Talk with your doctor about whether TRT is right for you. If you do not notice any change in symptoms after treatment for 3 months, it is less likely that TRT treatment will benefit you.

If you decide to start testosterone replacement therapy, be sure to see your doctor for regular checkups.

Prior to commencing TRT, all patients should undergo a baseline measurement of hemoglobin (Hb)/hematocrit (Hct). If the hematocrit (Hct) exceeds 50%, clinicians should consider withholding TRT until the cause of the high Hct is explained 121. Men with elevated Hct and on-treatment low/normal total and free testosterone levels should be referred to a hematologist for further evaluation, and possible coordination of phlebotomy. Testosterone has a stimulating effect on erythropoiesis, and elevation of Hb/Hct is the most frequent adverse event related to TRT 122. During TRT, levels of hemoglobin (Hb)/hematocrit (Hct) generally rise for the first six months, then tend to plateau 124.

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) should be measured in men over 40 years of age prior to commencement of TRT to exclude a prostate cancer diagnosis 125. PSA secretion is an androgen-dependent phenomenon, and the rise of PSA levels in patients on TRT is primarily dependent on baseline total testosterone levels. A previous study found that men with lower baseline testosterone levels were more likely to experience PSA level increases after TRT 126. In that study, participants (N = 451) received 5–10 g of 1% Testosterone gel daily for 12 months. Patients were divided into two groups: A (n = 197 with total testosterone <250 ng/dL) and B (n = 254 with total testosterone ≥250 ng/dL). In Group A, but not Group B, baseline PSA levels correlated significantly with total testosterone levels. At the end of follow-up, PSA increased significantly in Group A (21.9% change; 0.19 ± 0.61 ng/mL), but not in Group B (14.1% change; 0.28 ± 1.18 ng/mL), with the greatest PSA change observed after one month of treatment 126.

The effects of TRT on cardio vascular disease (CVD) remain a point of concern. Ferrucci et al. 127 showed that low testosterone levels had an independent influence on the development of anemia in older adults. Testosterone stimulates the production of erythropoietin-responsive cells and burst-forming units in the bone marrow, which boosts iron absorption and erythropoiesis 128. The effects of testosterone on the bone marrow affecting the hematopoietic growth factors and iron absorption show the association between testosterone and erythropoiesis. In an earlier study 129, data demonstrated that subjects with low total testosterone and free testosterone levels had low Hb and Hct levels. This result suggests that low total testosterone and free testosterone may play a significant role in erythropoiesis. According to a recent study 130, TRT in older men with low testosterone levels significantly increased hemoglobin (Hb) levels of those with unexplained anemia, as well as those with anemia from known causes. Measurement of testosterone levels might be considered in men 65 years or older who have unexplained anemia and symptoms of low testosterone levels. Although men with hypogonadism were not always anemic in our previous study, the association between low testosterone and low hemoglobin (Hb) levels was statistically significant 129. Furthermore, our previous study noted that the prevalence of anemia decreased, and patients with anemia showed increased erythropoietin after TRT 131. TRT may be effective in men with hypogonadism to reduce the incidence of anemia and the cardiovascular disease associated with anemia Saad, F., Doros, G., Haider, K. S., & Haider, A. (2018). Hypogonadal men with moderate-to-severe lower urinary tract symptoms have a more severe cardiometabolic risk profile and benefit more from testosterone therapy than men with mild lower urinary tract symptoms. Investigative and clinical urology, 59(6), 399–409. https://doi.org/10.4111/icu.2018.59.6.399.

Testosterone replacement therapy

Testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) is an important treatment option for men with low testosterone and symptomatic hypogonadism. Male hypogonadism also known as testosterone deficiency, is defined as having one or more symptoms attributable to low circulating levels of testosterone (serum total testosterone <300 ng/dL) 12, 10. Although controversy remains regarding indications for testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) in aging men due to lack of large-scale, long-term studies assessing the benefits and risks of testosterone-replacement therapy in men, reports indicate that TRT has been shown to increase serum testosterone to physiologic levels, which may produce a wide range of benefits for men with hypogonadism that include improve libido, improve erectile dysfunction, improve overall sexual function, increase bone mineral density, decrease body fat mass, and increase lean body muscle mass, increase energy, improve mood, erythropoiesis, cognition, quality of life and cardiovascular disease 132. The TIMES2 (Testosterone replacement In hypogonadal men with either MEtabolic Syndrome or type 2 diabetes) study 133 showed that testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) improved glycemic control, lipid levels, sexual function and libido in men with type 2 diabetes and/or metabolic syndrome, with no corresponding increase in adverse events.

The most controversial area for TRT is the issue of risk, especially possible stimulation of prostate cancer by testosterone, even though no evidence to support this risk exists. A 2021 study 134 concluded that compared to TRT-untreated patients, TRT-treated patients may not have increased risks for disease progression in prostate cancer. However, the quality of currently available evidence is extremely poor. TRT may be harmful in men with advanced prostate cancer, in those with untreated prostate cancer undergoing active surveillance, and in those with successfully treated prostate cancer but having high-risk disease 134. The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) stated, in all testosterone package inserts, that TRT is contraindicated in men with known or suspected prostate cancer, but it did not substantiate this contraindication 135. The clinical guidelines by Endocrine Society recommend against treating hypogonadism in men with prostate cancer, citing lack of sufficient data to make a general recommendation in men previously treated for prostate cancer (‘recommendation with low quality evidence’) 14. Meanwhile, the European Association of Urology stated that there is no conclusive evidence that TRT increases the risk of prostate cancer (‘level of evidence=4’), and that men with prostate cancer can receive TRT with careful monitoring for prostate safety (‘level of evidence=3’) 136. Similarly, the recent treatment guideline by the American Urologic Association stated that patients should be informed that there is inadequate evidence for TRT (‘expert opinion’), but TRT can be considered in men who have undergone radical prostatectomy with favorable pathology (e.g., negative margins, negative seminal vesicles, negative lymph nodes), without PSA recurrence 12.

Currently, there are a variety of widely available testosterone formulations, including topical gels and patches, intramuscular injections, subcutaneous pellets, and oral/buccal formulations that provide clinicians and male patients the opportunity to personalize replacement therapy to reestablish testosterone levels and improve testosterone deficiency symptoms 137:

- Exogenous Testosterone Replacement Therapy

- Mechanism of action: Restore testosterone levels by supplementing various preparations of natural testosterone

- Types: Oral, buccal, intramuscular, transdermal, subdermal, and nasal preparations

- Gel. There are several gels and solutions available, with different ways of applying them. Depending on the brand, you rub the testosterone into your skin on your upper arm or shoulder (AndroGel, Testim, Vogelxo) or apply it to the front and inner thigh (Fortesta). Your body absorbs testosterone through your skin. Don’t shower or bathe for several hours after a gel application, to be sure it gets absorbed. Side effects include skin irritation and the possibility of transferring the medication to another person. Avoid skin-to-skin contact until the gel is completely dry, or cover the area after an application.

- Injection. Testosterone cypionate (Depo-Testosterone) and testosterone enanthate are given in a muscle or under the skin. Your symptoms might waver between doses depending on the frequency of injections. You or a family member can learn to give testosterone injections at home. If you’re uncomfortable giving yourself injections, member of your care team can give the injections. Testosterone undecanoate (Aveed) is given by deep intramuscular injection, typically every 10 weeks. It must be given at your provider’s office and can have serious side effects.

- Patch. A patch containing testosterone (Androderm) is applied each night to your thighs or torso. A possible side effect is severe skin reaction.

- Gum and cheek (buccal cavity). A small putty-like substance, gum-and-cheek testosterone replacement delivers testosterone through the natural depression above your top teeth where your gum meets your upper lip (buccal cavity). This product, taken three times a day, sticks to your gumline and allows testosterone to be absorbed into your bloodstream. It can cause gum irritation.

- Nasal. This testosterone gel (Natesto) can be pumped into the nostrils. This option reduces the risk that medication will be transferred to another person through skin contact. Nasal-delivered testosterone must be applied twice in each nostril, three times daily, which might be more inconvenient than other delivery methods.

- Implantable pellets. Testosterone-containing pellets (Testopel) are surgically implanted under the skin every three to six months. This requires an incision.

- Advantages:

- Multiple routes of administration depending on patient preference and needs

- Improves low testosterone levels and maintains virilization in hypogonadal men

- Particularly useful for treating hypergonadotropic hypogonadism in which testosterone levels are low but LH levels are high

- Limitations:

- Because it mimics functions of endogenous testosterone, it also exerts negative feedback on the hypothalamus and pituitary gland, reducing LH and decreasing endogenous intratesticular testosterone production

- Decreases intratesticular testosterone, impairs spermatogenesis, and results in male infertility

- Therapies that Increase Endogenous Testosterone

- Mechanism of action: Multiple mechanisms of action by affecting various points along the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis to increase

- Types: Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), Gonadotropins, Aromatase inhibitors, Selective androgen receptor modulators (SARMs), Leydig stem cell transplantation

- Advantages:

- Able to increase serum and intratesticular testosterone levels

- Greater likelihood of preserving hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis axis function and, subsequently, spermatogenesis and fertility

- Limitations:

- Potential unintended decline in quality of semen and complications related to changes in estrogen levels

- None have been approved by the US FDA specifically for men with hypogonadism or infertility.

Table 2. Testosterone replacement therapy formulations

| Names | Strengths | Limitations | Comparative Efficacy | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Testosterone undecanoate |

|

|

| Nieschlag 2015 139, Swerdloff et al. 2020 140 |

| Striant (testosterone buccal) |

|

| Tsametis & Isidori 2018 143, Dinsmore & Wyllie 2012 144 | |

Long acting testosterone:

Extra-long acting testosterone:

|

|

|

| Nieschlag 2015 139, Tsametis & Isidori 2018 143, Middleton et al. 2015 146 |

Testosterone Gel:

Testosterone Solution:

Testosterone Patch:

|

|

|

| Tsametis & Isidori 2018 143 |

Testosterone implant:

|

|

| Tsametis & Isidori 2018 143 | |

Testosterone nasal:

|

|

|

| Tsametis & Isidori 2018 143, Gronski et al. 2019 151, Rogol et al. 2018 152 |

Oral testosterone

Currently, the most commonly available oral preparation is testosterone undecanoate 137. This preparation is able to avoid first passing through the liver due to its aliphatic side chain which allows it to be absorbed by the lymph system and directly enter the circulatory system 153. This formulation requires more frequent and larger doses in order to effectively replete testosterone therapy 154. Resent study reported that although oral testosterone undecanoate is a safe and effective means to treat hypogonadal men, it was related to a small but significant increased systolic blood pressure 140. While it has shown efficacy, pharmacokinetic analysis has proven that it is difficult to predict absorption due to high intra- and inter-individual variability in serum concentrations. Oral Testosterone undecanoate also includes a black box warning regarding blood pressure increases and risk of cardiac events, which makes its use a major concern for older men. An additional group of oral agents exist that have been available for decades; these are 17-alpha alkylated androgens (methyltestosterone and fluoxymesterone). However, many reports have implicated these oral preparations in cholestatic jaundice, a hepatic cystic disease called peliosis hepatis, and hepatoma 138. Therefore, oral testosterone undecanoate are no longer suggested for use due to the discovery of extreme liver toxicity and minimal effectiveness in resolving hypogonadal symptoms.

Buccal testosterone

Currently, the most commonly available buccal preparation is a buccal tablet (Striant®) which exists as a potential therapeutic option for patients who can tolerate it 137. The tablets are mucoadhesive and are applied to a depression in the gum above the upper incisors, slowly releasing testosterone into the circulatory system. Twice daily applications of 30 mg tablets result in stable serum levels of testosterone. The benefits of this method are that the effects can quickly be reversed and the release of medication mimics circadian rhythms 155. However, it has also been shown that 3-15% of patients may experience irritation, inflammation, or gingivitis while also having difficulty from complaints due to the unique method of delivery 143. These potential side effects should be taken into consideration when opting for this method of TRT.

Testosterone intramuscular injections

Intramuscular injection of testosterone has proven to be effective in initiating and maintaining virilization in all hypogonadal men 155. Current options include long-acting (testosterone enanthate and testosterone cypionate) and extra-long-acting (testosterone undecanoate) variants. The long-acting options are esters of testosterone which make the molecule more lipophilic than the natural variant. This results in their storage and gradual release, thereby prolonging the presence of testosterone in the blood 156. Administration of long-acting intramuscular testosterone usually occurs as 50–100 mg every week, 100–200 mg every 2 weeks, or 250 mg every 3 weeks and has shown consistent results 155. The advantages of long-acting options are that they are extremely effective, easily accessible, and cost effective, and they free patients from daily administration. Conversely, the disadvantages are the need for patients to be comfortable with deep intramuscular administration of the testosterone solution and fluctuations in energy, mood, and libido in many patients.

An extra-long-acting option exists with testosterone undecanoate in oil, which is also one of the common oral options. When injected alongside castor oil, a half-life of 34 days is observed 153. Each dose is 750 mg in 3mL of oil. The recommendations for administration in the United States are to administer a dose into the buttocks, followed by a second dose 4 weeks later, and then subsequent doses every 10 weeks. Access to this option is regulated by a restricted program called the AVEED Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) Program and is not recommended consistently. Although the injectable preparation is generally considered safe, patients must be monitored for pulmonary oil micro-embolism (POME) 157. Symptoms of POME (pulmonary oil micro-embolism), such as sudden onset of non-productive cough associated with faintness following injections, have been observed in 1.5% of patients 158. Additionally, anaphylactic responses have been observed in some patients, requiring 30-min post-dose monitoring to rule out this side effect 155. The advantages of less frequent administration come at the cost of various systemic side effects that require regular monitoring.

Transdermal testosterone

Transdermal testosterone preparations are known to provide very stable and effective improvements in serum testosterone levels due to their pharmacokinetic profile which mimics physiological diurnal variations. Transdermal testosterone preparations include preparations that incorporate solutions, gels, and patches. Three testosterone gels (AndroGel®, Testim®, and Fortesta®), one solution (Axiron®), and one patch (Androderm®) are available in the United States 155. Transdermal testosterone substitution has the following advantages: a) since they have a short duration of action, the preparations can be quickly discontinued if any adverse effect occurs and the testosterone levels will then quickly decline, and b) they are easy to use and easily accessible to many. Conversely, the disadvantages include the need for daily administration, relatively high cost, skin irritation, and the risk of contact transfer to another person 144. The high risk of unintentional transfer led the FDA to require testosterone gel products to include a Blackbox warning. They have also been shown to be less effective in obese individuals and require higher doses 155. However, due to the ease of use, accessibility, and reversibility, these are often a first-line choice for patients who require testosterone substitution.

Subdermal testosterone

Subdermal pellet implants (Testopel®) are a viable option for testosterone replacement and result in stable testosterone levels. The pellets are implanted into the subdermal fat of the buttocks, lower abdominal wall, or thigh with a tunneling technique using a local anesthetic 159. It is recommended that three to six 75 mg pellets should be implanted every 4-6 months (150 mg-450 mg) to achieve stable testosterone levels in the normal range 155. The benefits of this method include guaranteed compliance and lack of transference to persons who may come in contact with it 155. Adverse effects include pellet extrusion, infection, and fibrosis 160. Due to the need for a surgical procedure for implantation and the potential side effects, this form of TRT is usually not recommended as first-line treatment 146.

Nasal testosterone

A nasal testosterone gel, known as Natesto®, is now available in the United States for treatment of male hypogonadism. Studies have shown successful treatment with this new method and have exhibited consistent improvements in testosterone deficiency 161. This gel is administered in the nostrils via a metered dose pump which delivers 5.5mg per actuation. The recommended dosage is to administer one actuation in each nostril three times daily, resulting in a daily dosage of 33 mg/day. This method has shown a reduction in gel transfer to a partner or child due to the inconspicuous application site, and it provides ease of use as a non-invasive option. Most importantly, preliminary studies have demonstrated that Natesto® increases serum testosterone while also maintaining FSH, LH, and semen parameters 162. Natesto nasal testosterone gel can maintain spermatogenesis in >95% of men, in contrast to injections or gels 150. Also, significant differences have been observed between duration of action, frequency of administration and clinical pharmacokinetic profile of Natesto compared to long-acting testosterone injections, gels and pellets 152. On the other hand, more than 3% of men have reported experiencing rhinorrhea, epistaxis, nasopharyngitis, sinusitis, and nasal scab as a result of this medication 155. Unique among the formulations of exogenous TRT, nasal formulations of testosterone are showing promise in alleviating symptoms of low testosterone without adversely affecting the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis.

Table 3. Therapies that increase endogenous testosterone

| Class | Mechanism of Action | Strengths | Limitations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs) |

|

|

| El Meliegy et al. 2018 163, Chehab et al. 2015 164 |

| Gonadotropins |

|

|

| Lee & Ramasamy 2018 165, El Meliegy et al. 2018 163, Dohle et al. 2016 166 |

| Aromatase Inhibitors |

|

|

| Crosnoe et al. 2013 167, El Meliegy et al. 2018 163, Ribeiro et al. 2016 168 |

| Selective Androgen Receptor Modulators (SARMs) |

|

|

| Narayanan et al. 2018 169, Solomon et al. 2018 170 |

| Leydig Stem Cell Transplantation |

|

|

| Zang et al. 2017 171, Beattie et al. 2015 172, Arora et al. 2019 173 |

Selective estrogen receptor modulators

Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) are a group of pharmaceuticals that act as competitive inhibitors of estrogen receptors in the hypothalamus and pituitary with the increasing release of GnRH and gonadotrophins, subsequently increasing production of intra-testicular testosterone and improving spermatogenesis 174. Clomiphene citrate is a SERM that has been used in the treatment of men with azoospermia, oligozoospermia, and unexplained infertility, in addition to treating male hypogonadism. It has been demonstrated that Clomiphene citrate leads to a moderate increase in FSH, LH, total testosterone, and the concentration of sperm in these men 175. Also, in men with late-onset hypogonadism, long-term Clomiphene citrate therapy can be prescribed as a testosterone replacement 174. Although thromboembolic events and carcinogenesis have been reported as adverse effects of SERMs 176, current ongoing research shows that this group of pharmaceuticals has great potential for future applications 177.

Gonadotropins