Contents

- Morphine

- Morphine mechanism of action

- Morphine special precautions

- Morphine uses

- Morphine contraindications

- Morphine dosage

- Morphine side effects

- Morphine withdrawal

- Morphine Addiction

- Morphine overdose

- Naloxone

- How to use and give naloxone

- Naloxone injection instructions

- Naloxone nasal spray instructions

- After giving a dose of naloxone

- How is naloxone given?

- What if I’m not sure if someone has an opioid overdose?

- Is naloxone safe?

- What are the different types of naloxone?

- Is there a preferable naloxone delivery system?

- Where can I get naloxone?

- How much does naloxone cost?

- How does naloxone work?

- Naloxone

Morphine

Morphine is an opioid medicine or a very strong painkiller only available via prescription from your doctor often prescribed for severe pain when other pain-relief medicines are not effective or cannot be used. Morphine should only be used when other forms of pain relief have not been successful in managing your pain or if you are not able to take them (for example, because of side effects or because your doctor says you cannot take it together with another medicine that you are taking). Morphine is in a class of medications called opioids or opiates or narcotic analgesics, which is a natural alkaloid that is derived from resin extracts from the seeds of the opium poppy plant (Papaver somniferum) and is used for pain relief (analgesic) or calming effects 1. Morphine works by changing the way the brain and nervous system respond to pain. Morphine is a controlled substance and classified as a Schedule 2 drug, indicating that morphine has medical usefulness, but also a high potential for physical and psychological dependency and abuse.

Common effects of morphine include:

- Euphoria (a feeling or state of intense excitement, well-being and happiness)

- Pain relief

- Sleepiness or unusual drowsiness

- Reduced anxiety

- False or unusual sense of well-being

- Relaxed or calm feeling

Morphine is available in multiple formulations, including oral tablets and syrups, suppositories, and solutions for injection in multiple concentrations via subcutaneous (injection under your skin), intravenous (IV), intramuscular (IM), epidural, and intrathecal 2. Morphine administration can occur through various routes most often via the following routes: orally (PO), suppository, intravenously (IV), epidural, and intrathecal. Morphine oral formulations are available in both immediate-release (IR) tablets and oral solution are used to relieve severe, acute pain (pain that begins suddenly, has a specific cause, and is expected to go away when the cause of the pain is healed) and chronic pain in people who are expected to need an opioid pain medication and who cannot be treated with other pain medications. Sublingual morphine is very popular in palliative care. Morphine extended-release (ER) tablets and capsules are used to relieve severe and persistent pain in people who are expected to need an opioid pain medication around the clock and who cannot be treated with other pain medications. Morphine extended-release tablets and capsules should not be used to treat pain that can be controlled by medication that is taken on “as needed” (PRN) basis.

Short acting or immediate-release (IR) morphine lasts for 2 to 4 hours per dose. Most people start on a short acting morphine or immediate-release (IR) tablet or liquid. This is because it is easier and quicker to adjust the dose. Once your pain is under control, you might change to a long acting or extended release (ER) tablet or capsule. Long acting or extended release (ER) morphine lasts from 12 to 24 hours per dose. You take it either once or twice a day. If you are taking or extended release (ER) morphine twice a day, you should take it in the morning and at night, for example at 8am and 8pm. It is important that you take morphine regularly, even if you don’t feel pain. The slow release or extended release (ER) morphine tablets or capsules can take up to 48 hours to give you a steady dose. So if you stop and start, they won’t work so well.

Pain that is more severe and not well controlled with oral morphine may be manageable with single or continuous doses of subcutaneous, intravenous (IV), epidural, and intrathecal morphine 3. Morphine infusion dosing can vary significantly between patients and largely depends on how naive or tolerant patients are to opiates. It is interesting to point out that IV morphine formulation is also commonly given intramuscularly (IM).

The typical dose of morphine for pain relieve in adults is 10 mg every 3 to 4 hours by the subcutaneous, intramuscular or intravenous route. Morphine is well absorbed orally, but has extensive and variable first pass metabolism, so that its effect orally is somewhat variable.

Your doctor or specialist will help you choose the type and dose of morphine that best controls your pain. It depends on the pain you have and the amount of drug you need to control it.

When morphine is used for a long time, it may become habit-forming, causing mental or physical dependence. However, people who have continuing pain should not let the fear of dependence keep them from using narcotics to relieve their pain. Mental dependence (addiction) is not likely to occur when narcotics are used for this purpose. Physical dependence may lead to withdrawal side effects if treatment is stopped suddenly. However, severe withdrawal side effects can usually be prevented by gradually reducing the dose over a period of time before treatment is stopped completely.

The most common side effect of morphine use is constipation. The constipation side effect of morphine occurs via stimulation of mu (μ) opioid receptors on the myenteric plexus, which in turn inhibits gastric emptying and reduces peristalsis. Constipation is easier to sort out if you treat it early. Drink plenty of water and eat as much fresh fruit and vegetables as you can. Try to take gentle exercise, such as walking. Tell your healthcare team if you think you are constipated. They can give you a laxative if needed.

Other common side effects of morphine include central nervous system depression, lightheadedness, dizziness, sedation, slow your breathing, confusion, euphoria, dysphoria, agitation, dry mouth, anorexia, itching, abdominal bloating, urinary retention, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea. Severe side effects of morphine include life-threatening respiratory depression, addiction, abuse, opioid withdrawal, biliary spasm, serotonin syndrome (when used with serotonergic agents) and adrenal insufficiency 4.

Morphine may cause other serious side effects. See your doctor at once or get emergency medical treatment if you have:

- slow heart rate, weak pulse, fainting, slow breathing (breathing may stop),

- chest pain, fast or pounding heartbeats,

- extreme drowsiness, feeling like you might pass out,

- decreased adrenal gland hormones – nausea, vomiting, stomach pain, loss of appetite, feeling tired or light-headed, muscle or joint pain, skin discoloration, craving salty foods.

Respiratory depression (slow breathing) is among the more serious side effects with morphine use and death may occur, especially if you drink alcohol or use other drugs that cause drowsiness or slow your breathing 5. Serious breathing problems may be more likely in older adults and people who are debilitated or have wasting syndrome or chronic breathing disorders. A person caring for you should give naloxone and/or seek emergency medical attention if you have slow breathing with long pauses, blue colored lips, or if you are hard to wake up.

Patients using morphine often report nausea and vomiting, which is why in many emergency departments, morphine administration is with a drug that is effective against vomiting and nausea (antiemetic drug) such as ondansetron 6. Other side effects include biliary tract spasm, which is why some doctors will avoid morphine when patients present with right upper quadrant pain and they suspect possible biliary tract pathology. Morphine can also affect the cardiovascular system and reportedly can cause flushing, a slow heart rate, low blood pressure, and fainting. It is also important to note that patients can experience itch, hives, swelling, and other skin rashes 1.

Figure 1. Morphine

Morphine may be habit forming, especially with prolonged use. You should not take morphine if you have severe asthma or breathing problems, a blockage in your stomach or intestines, or a bowel obstruction called paralytic ileus. Take morphine exactly as directed. Do not take more of it, take it more often, or take it in a different way than directed by your doctor. While you are taking morphine, discuss with your healthcare provider your pain treatment goals, length of treatment, and other ways to manage your pain. Tell your doctor if you or anyone in your family drinks or has ever drunk large amounts of alcohol, uses or has ever used street drugs, or has overused prescription medications, or has had an overdose, or if you have or have ever had depression or another mental illness. There is a greater risk that you will overuse morphine if you have or have ever had any of these conditions. Talk to your healthcare provider immediately and ask for guidance if you think that you have an opioid addiction or call the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP.

Morphine may cause serious or life-threatening breathing problems, especially during the first 24 to 72 hours of your treatment and any time your dose is increased. Your doctor will monitor you carefully during your treatment. Your doctor will adjust your dose carefully to control your pain and decrease the risk that you will experience serious breathing problems. Tell your doctor if you have or have ever had slowed breathing or asthma. Your doctor may tell you not to take morphine. Also tell your doctor if you have or have ever had lung disease such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD; a group of lung diseases that includes chronic bronchitis and emphysema), a head injury, a brain tumor, or any condition that increases the amount of pressure in your brain. The risk that you will develop breathing problems may be higher if you are an older adult or are weakened or malnourished due to disease. If you experience any of the following symptoms, call your doctor immediately or get emergency medical treatment: slowed breathing, long pauses between breaths, or shortness of breath.

Do not allow anyone else to take your medication. Morphine may harm or cause death to other people who take your medication, especially children. Keep morphine in a safe place so that no one else can take it accidentally or on purpose. Be especially careful to keep morphine out of the reach of children. Keep track of how many tablets or capsules, or how much liquid is left so you will know if any medication is missing. Dispose of any unneeded morphine tablets, capsules, or liquid properly according to instructions. (See STORAGE and DISPOSAL.)

Taking certain other medications during your treatment with morphine may increase the risk that you will experience breathing problems or other serious, life-threatening breathing problems, sedation, or coma. Tell your doctor and pharmacist what prescription and nonprescription medications, vitamins, nutritional supplements, and herbal products you are taking or plan to take. If you take morphine with other medications and you develop any of the following symptoms, call your doctor immediately or seek emergency medical care: unusual dizziness, lightheadedness, extreme sleepiness, slowed or difficult breathing, or unresponsiveness. Be sure that your caregiver or family members know which symptoms may be serious so they can call the doctor or emergency medical care if you are unable to seek treatment on your own.

Drinking alcohol, taking prescription or nonprescription medications that contain alcohol, or using street drugs during your treatment with morphine increases the risk that you will experience breathing problems or other serious, life-threatening side effects. If you are taking long-acting capsules, it is especially important that you do not drink any drinks that contain alcohol or take any prescription or nonprescription medications that contain alcohol. Alcohol may cause the morphine in long-acting capsules to be released in your body too quickly, causing serious health problems or death. Do not drink alcohol, take any prescription or nonprescription medications that contain alcohol, or use street drugs during your treatment with morphine products.

Swallow the extended-release tablets or capsules whole. Do not split, chew, dissolve, or crush them. If you swallow broken, chewed, crushed, or dissolved extended-release tablets or capsules, you may receive too much morphine at once instead of receiving the medication slowly over time. This may cause serious breathing problems or death. If you are unable to swallow the extended-release capsules, you can carefully open a capsule, sprinkle all of the beads that it contains on a spoonful of cold or room temperature applesauce, and swallow the entire mixture immediately without chewing or crushing the beads. Then rinse your mouth with a little water and swallow the water to be sure that you have swallowed all the medication. Do not mix the beads into any other food. Do not save mixtures of medication and applesauce for later.

Morphine oral solution (liquid) comes in three different concentrations (amount of medication contained in a given amount of solution). The solution with the highest concentration (100 mg/5 mL) should only be taken by people who are tolerant (used to the effects of the medication) to opioid medications. Each time you receive your medication, check to be sure that you receive the solution with the concentration prescribed by your doctor. Be sure that you know how much medication you should take and how to measure your dose.

Tell your doctor if you are pregnant or plan to become pregnant. If you take morphine regularly during your pregnancy, your baby may experience life-threatening withdrawal symptoms after birth. Tell your baby’s doctor right away if your baby experiences any of the following symptoms: irritability, hyperactivity, abnormal sleep, high-pitched cry, uncontrollable shaking of a part of the body, vomiting, diarrhea, or failure to gain weight.

Your doctor or pharmacist will give you the manufacturer’s patient information sheet (Medication Guide) when you begin treatment with morphine and each time you fill your prescription if a Medication Guide is available for the morphine product you are taking. Read the information carefully and ask your doctor or pharmacist if you have any questions. You can also visit the manufacturer’s website to obtain the Medication Guide.

Morphine mechanism of action

Morphine is in a class of medications called opioids or narcotic analgesics (pain relievers or painkillers). Morphine-6-glucuronide (M6G) is responsible for approximately 85% of the response observed by morphine administration 7. Like other opioid medications, morphine has an affinity for mu (μ), kappa (κ), and delta (δ) opioid receptors 8. Morphine produces most of its pain relieving (analgesic) effects by binding to the mu (μ) opioid receptor within the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) and the peripheral nervous system (the nervous system outside the brain and spinal cord), including also the heart, lung, vascular and intestinal cells 9, 7. More specifically, the central nervous system mu (μ) opioid receptors are present in various crucial regions, including the cerebellum, nucleus accumbens, the caudate nucleus of the brain, putamen, cerebral cortex, substantia nigra, and spinal cord 10. Receptors located in the peripheral nervous system (the nervous system outside the brain and spinal cord) that contribute to the analgesic properties of opioids include the dorsal root ganglion. Opioid agonists bind to G-protein–coupled receptors, initiating intracellular transduction pathways that involve inhibiting adenylyl cyclase, stimulating potassium efflux, and inhibiting calcium influx. Consequently, these changes reduce intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), cell hyperpolarization, and neurotransmitter release inhibition 11. The net effect of morphine is the activation of descending inhibitory nerve pathways of the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) as well as impeding the pain afferent neurons of the peripheral nervous system (the nervous system outside the brain and spinal cord), which leads to an overall reduction of the pain transmission.

When morphine is administered in the epidural space, it is rapidly absorbed into the systemic circulation. Peak plasma concentrations are reached within 10 to 15 minutes, whereas peak CSF concentrations are achieved within 60 to 90 minutes after injection. Morphine has a half life of 2-3 hours 12. The primary clearance pathway involves hepatic glucuronidation facilitated by UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) enzymes, leading to the formation of morphine-3-glucuronide, which is pharmacologically inactive 13. Morphine and its metabolites are primarily excreted via the kidneys in the urine with 2-10% of a dose recovered as the unchanged parent drug 7. About 70-80% of an administered morphine dose is excreted within 48 hours 14. Approximately 10% of the administered dose of morphine is eliminated in the feces 15. Notably, the elimination of morphine metabolites is affected in patients with obesity and those who are critically ill 16, 17.

Morphine special precautions

Before using morphine:

- tell your doctor and pharmacist if you are allergic to morphine, any other medications, or ingredients in morphine injection. Ask your pharmacist for a list of the ingredients.

- tell your doctor if you have or have ever had any of the conditions mentioned in the IMPORTANT WARNING section, a blockage or narrowing of your stomach or intestines, or paralytic ileus (condition in which digested food does not move through the intestines). Your doctor may tell you not to use morphine.

- tell your doctor if you have or have ever had seizures; low blood pressure; problems urinating; adrenal insufficiency (condition in which the adrenal glands do not produce enough of certain hormones needed for important body functions);or pancreas, gallbladder, heart, liver, or kidney disease.

- tell your doctor if you are breastfeeding. You should not breastfeed while you are using morphine. Morphine can cause shallow breathing, difficulty or noisy breathing, confusion, more than usual sleepiness, trouble breastfeeding, or limpness in breastfed infants.

- you should know that morphine may decrease fertility in men and women. Talk to your doctor about the risks of using morphine.

- if you are having surgery, including dental surgery, tell the doctor or dentist that you are using morphine.

- you should know that morphine may make you drowsy. Do not drive a car or operate machinery until you know how morphine affects you.

- you should know that morphine may cause dizziness, lightheadedness, and fainting when you get up too quickly from a lying position. To avoid this problem, get out of bed slowly, resting your feet on the floor for a few minutes before standing up.

- you should know that morphine may cause constipation. Talk to your doctor about changing your diet or using other medications to prevent or treat constipation while you are using morphine.

- if you have been using morphine regularly for several weeks or longer, do not change your dose or suddenly stop using it without checking with your doctor. Your doctor may want you to gradually reduce the amount you are using before stopping it completely. This may help prevent worsening of your condition and reduce the possibility of withdrawal symptoms, including stomach cramps, anxiety, fever, nausea, runny nose, sweating, tremors, or trouble sleeping.

Allergies

Tell your doctor if you have ever had any unusual or allergic reaction to morphine or any other medicines. Also tell your doctor if you have any other types of allergies, such as to foods, dyes, preservatives, or animals. For non-prescription products, read the label or package ingredients carefully.

Morphine may cause a serious allergic reaction called anaphylaxis, which can be life-threatening and requires immediate medical attention. See your doctor right away if you have a rash, itching, hoarseness, trouble breathing or swallowing, or any swelling of your hands, face, or mouth while you are using morphine.

Children

Appropriate studies have not been performed on the relationship of age to the effects of morphine epidural injection in the pediatric population. Use of morphine epidural injection is not recommended in children.

Elderly patients

Appropriate studies performed to date have not demonstrated geriatric-specific problems that would limit the usefulness of morphine epidural injection in the elderly. However, elderly patients are more likely to have age-related heart, stomach, or lung problems, which may require caution and an adjustment in the dose for patients receiving morphine epidural injection.

Pregnancy

Morphine may harm an unborn baby. Tell your doctor if you are pregnant or plan to become pregnant. If you use morphine during pregnancy, your baby could be born with life-threatening withdrawal symptoms and may need medical treatment for several weeks.

Long-term morphine use may affect fertility in men or women. Pregnancy could be harder to achieve while either parent is using morphine.

Breastfeeding

Do not breastfeed when using morphine, as morphine in breast milk can cause life-threatening side effects in your baby.

For mothers using morphine:

- Talk to your doctor if you have any questions about taking morphine or about how it may affect your baby.

- See your doctor if you become extremely tired and have difficulty caring for your baby.

- Your baby should generally nurse every 2 to 3 hours and should not sleep more than 4 hours at a time.

- Check with your doctor, hospital emergency room, or local emergency services immediately if your baby shows signs of increased sleepiness (more than usual), difficulty breastfeeding, difficulty breathing, or limpness. These may be symptoms of morphine overdose and need immediate medical attention.

Drug Interactions

Although certain medicines should not be used together at all, in other cases two different medicines may be used together even if an interaction might occur. In these cases, your doctor may want to change the dose, or other precautions may be necessary. When you are receiving morphine, it is especially important that your healthcare professional know if you are taking any of the medicines listed below. The following interactions have been selected on the basis of their potential significance and are not necessarily all-inclusive.

Using morphine with any of the following medicines is not recommended. Your doctor may decide not to treat you with this medication or change some of the other medicines you take.

- Isocarboxazid

- Linezolid

- Methylene Blue

- Naltrexone

- Ozanimod

- Phenelzine

- Procarbazine

- Rasagiline

- Safinamide

- Samidorphan

- Selegiline

- Tranylcypromine

Using morphine with any of the following medicines is usually not recommended, but may be required in some cases. If both medicines are prescribed together, your doctor may change the dose or how often you use one or both of the medicines.

- Abrocitinib

- Acepromazine

- Aclidinium

- Adagrasib

- Alfentanil

- Almotriptan

- Alogliptin

- Alprazolam

- Alvimopan

- Amantadine

- Amiloride

- Amineptine

- Amiodarone

- Amitriptyline

- Amitriptylinoxide

- Amobarbital

- Amoxapine

- Amphetamine

- Anileridine

- Aripiprazole

- Aripiprazole Lauroxil

- Asenapine

- Asunaprevir

- Atorvastatin

- Atropine

- Azithromycin

- Baclofen

- Belladonna

- Bemetizide

- Bendroflumethiazide

- Benperidol

- Bentazepam

- Benzhydrocodone

- Benzphetamine

- Benzthiazide

- Benztropine

- Berotralstat

- Biperiden

- Boceprevir

- Bromazepam

Using morphine with any of the following medicines may cause an increased risk of certain side effects, but using both drugs may be the best treatment for you. If both medicines are prescribed together, your doctor may change the dose or how often you use one or both of the medicines.

- Chloroprocaine

- Epinephrine

- Esmolol

- Lidocaine

- Somatostatin

- Yohimbine

Other Interactions

Using morphine with ethanol (alcohol) is usually not recommended. Morphine will add to the effects of alcohol and other central nervous system (CNS) depressants. CNS depressants are medicines that slow down the nervous system, which may cause drowsiness or make you less alert. Some examples of CNS depressants are antihistamines or medicine for allergies or colds, sedatives, tranquilizers, or sleeping medicine, other prescription pain medicine or narcotics, medicine for seizures or barbiturates, muscle relaxants, or anesthetics, including some dental anesthetics. This effect may last for a few days after you stop using morphine. Check with your doctor before taking any of these medicines while you are using morphine.

Medical Problems

The presence of these medical problems may affect the use of morphine. Make sure you tell your doctor if you have any of these medical problems, especially:

- Asthma, severe or

- Head injury, suspected or known or

- Increased pressure in the head or

- Paralytic ileus (intestine stops working and may be blocked) or

- Respiratory depression (very slow breathing) or

- Shock (serious condition with very little blood flow in the body)—Should not be used in patients with these conditions.

- Breathing problems, severe (e.g., hypoxia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, COPD) or

- Enlarged prostate (BPH, prostatic hypertrophy) or

- Heart disease or

- Problems with passing urine—Use with caution. May increase risk for more serious side effects.

- Gallbladder disease or

- Hypotension (low blood pressure) or

- Sleep apnea syndrome (breathing problems during sleep) or

- Pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas) or

- Seizures, history of—Use with caution. May make these conditions worse.

What should I avoid while taking morphine?

Do not drink alcohol whilst you’re on morphine. Dangerous side effects or death could occur.

Morphine may make you dizzy, drowsy, confused, or disoriented. Avoid driving or do anything else that could be dangerous until you know how morphine will affect you. Dizziness or drowsiness can cause falls, accidents, or severe injuries. Also avoid getting up too fast from a sitting or lying position, or you may feel dizzy.

Monitoring

The effectiveness and therapeutic index of morphine are assessable with a combination of subjective and objective findings. Controlling pain, which is usually the first symptom evaluated in patients, is the ultimate goal of morphine use. Other essential parameters requiring monitoring include mental status, blood pressure, respiratory drive, and misuse/overuse 3. It is also important to monitor what other medications a patient is taking. This list includes but is not limited to prescription medications. All patients taking morphine should understand the need to avoid any other substances that could lead to respiratory depression (morphine contraindications below) 18. These medications include but are not limited to alcohol, additional opioids, benzodiazepines, and barbiturates. Patients can stop breathing at lower doses if combining morphine with any of these substances.

Morphine uses

Morphine or morphine sulfate is an opioid medicine that is FDA approved to relieve severe pain when alternative pain relief medicines are not effective or not tolerated, such as pain caused by 19:

- Pain after a major trauma (for example, an accident)

- Pain after surgery

- Labor pain in childbirth

- Cancer pain or palliative/end-of-life care

- Vaso-occlusive pain during sickle cell crisis

- Acute coronary syndrome (any condition caused by a sudden reduction or blockage of blood flow to your heart) or pain from angina pectoris. Patients that are actively having acute coronary syndrome are often given morphine in the emergency setting before going to the cath lab. Morphine can decrease heart rate, blood pressure, and venous return. Morphine can also stimulate local histamine-mediated processes 20. In theory, the combination of these can reduce heart muscle oxygen demand.

- Pain during a heart attack. Morphine to relieve pain during a heart attack (myocardial infarction) has been in use since the early 1900s 21.

- Pulmonary edema treatment.

Your doctor is the best person to advise you on whether morphine is the right medicine for you, how much you need and how long to take it for.

Morphine is also widely used off-label for almost any condition that causes pain. In the emergency department, morphine is given for muscle and joint pain, abdominal pain, chest pain, arthritis, and even headaches when patients fail to respond to first and second-line agents 3. Morphine is rarely used for procedural sedation. However, for small procedures, doctors will sometimes combine a low dose of morphine with a low dose of benzodiazepine like lorazepam.

Morphine contraindications

Use morphine with extreme caution in patients with severe respiratory depression and asthma exacerbation since morphine can further decrease the respiratory drive 1. Additionally, morphine should be avoided in cases of previous hypersensitivity reaction and immediately discontinued in the presence of an active anaphylactic reaction 22. Caution is also necessary with the concurrent use of monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) as these medications have an additive effect with morphine. Using morphine with monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) can then trigger severe low blood pressure, serotonin syndrome, or increase respiratory depression in patients 1. Gastrointestinal obstruction is another important contraindication to using morphine 19. It is also considered by many as a contraindication to provide opioids to individuals that have a history of substance misuse, especially if a patient has had a history of abusing opioids 1.

Morphine dosage

Take morphine exactly as prescribed by your doctor. Follow the directions on your prescription label and read all medication guides or instruction sheets. Never use morphine in larger amounts or for longer than prescribed. Tell your doctor if you feel an increased urge to use more morphine.

Your doctor may adjust your dose of morphine during your treatment, depending on how well your pain is controlled and on the side effects that you experience.

Morphine dosage general guidelines:

- Use the lowest effective dose for the shortest duration consistent with individual patient treatment goals.

- Initial dose recommendations should not be exceeded as this could result in an overdose with the first dose.

- Conversion from other opioids and between morphine formulations should be done cautiously and with increased monitoring as individuals have been shown to exhibit a wide variability to the potency of other opioid drugs and morphine formulations that cannot be accounted for with conversion tables.

Swallow morphine extended-release (ER) capsule or tablet whole to avoid a potentially fatal overdose. Do not crush, chew, break, open, or dissolve. Never crush a morphine pill to inhale the powder or inject it into your vein. This could result in death.

- Morphine extended-release (ER) capsules: Take orally once or twice a day.

- Swallow whole; crushing, chewing, or dissolving pellets will result in uncontrolled delivery of morphine and can lead to overdose

- For patients unable to swallow capsules whole, may open capsules and sprinkle contents on applesauce, swallow immediately without chewing

- Avoid alcohol: There is data to show the presence of alcohol increases the rate of release of morphine from the sustained-release pellets in the capsule

- French Gastrostomy Tube: Flush gastrostomy tube with water to ensure that it is wet; open extended-release capsule and sprinkle pellets into 10 mL of water; using a swirling motion pour pellets through a funnel into gastrostomy tube; rinse and repeat until no pellets remain

- Do not administer pellets through a nasogastric tube

- Morphine extended-release (ER) tablets: Take orally every 8 or 12 hours.

- Swallow whole, 1 tablet at a time; do not pre-moisten, cut, break, crush, chew, or dissolve as that will result in uncontrolled delivery of morphine and can lead to overdose

Morphine Oral solution: There are 3 concentrations available (2 mg/mL, 4 mg/mL, and 20 mg/mL); reserve use of 20 mg/mL concentration for patients who are opioid-tolerant. Measure liquid medicine dose with an appropriately calibrated measuring device (not a kitchen spoon).

Morphine intravenous (IV): Administer by slow IV injection; rapid IV administration may result in chest wall rigidity.

Morphine intramuscular (IM):

- Intramuscular (IM) administration is generally not the recommended route of administration due to its painful administration, wide fluctuations in muscle absorption, 30 to 60-minute lag to peak effect, and rapid fall in analgesia compared to oral administration.

- Auto-Injectors: The spring-driven injection mechanism is capable of inflicting injury if accidentally misused; keep product in its original container with safety in place until use

- Caution must be used when injecting any opioid IM into chilled areas or in patients with hypotension or shock, since impaired perfusion may prevent complete absorption; if repeated injections are administered, an excessive amount may be suddenly absorbed if normal circulation is re-established.

Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA):

Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) is a type of pain management that uses a computerized pump attached to the intravenous (IV) line and the pain medicine is given through the pump through an IV line placed into your vein. Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) lets you decide by pressing a handheld button when you will get a dose of pain medicine.

Preservative-free morphine injection should be used with a compatible patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pump set with injector and a compatible infusion device; multiple concentrations are available for use with PCA infusion device (0.5, 1 and 5 mg/mL); the manufacturer product information should be consulted for additional information.

Neuraxial drug administration:

Neuraxial drug administration describes techniques that deliver drugs in close proximity to the spinal cord, i.e. intrathecally into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or epidurally into the fatty tissues surrounding the dura, by injection or infusion. Neuraxial morphine administration is for the management of pain severe enough to require opioid analgesia by epidural or intrathecal management without attendant loss of motor, sensory, or sympathetic function. Patients must be observed in a fully equipped and staffed environment for at least 24 hours after each test dose and, as appropriate, for the first several days after catheter implantation.

- Neuraxial administration may result in acute or delayed respiratory depression up to 24 hours; patients must be observed in a fully equipped and staffed environment for at least 24 hours and longer as clinically appropriate

- Duramorph (morphine injection) is NOT for use in continuous microinfusion devices

- Infumorph (morphine sulfate injection) is morphine pain reliever indicated only for intrathecal or epidural infusion in the treatment of intractable chronic pain. Infumorph is for use in continuous microinfusion devices and not for single-dose injection because it is too concentrated.

- For safety reasons, it is recommended that administration by the epidural or intrathecal routes be limited to the lumbar area.

- The manufacturer product information should be consulted for additional information.

Adult Dose for Acute Pain

For the management of acute pain severe enough to require an opioid analgesic and for which alternative treatments are inadequate. Take morphine exactly as prescribed by your doctor taking into account severity of your pain. Follow the directions on your prescription label and read all medication guides or instruction sheets. Never use morphine in larger amounts or for longer than prescribed.

Comments:

- Monitor closely for respiratory depression, especially within the first 24 to 72 hours of initiating therapy and with all dose increases.

- Because of the risks of addiction, abuse, and misuse with opioids, reserve use for patients for whom alternative treatment options (e.g., non-opioid analgesics or opioid combination products) are ineffective, not tolerated, or would be otherwise inadequate to provide sufficient management of pain.

Oral morphine immediate-release

- Opioid-Naive and Opioid Non-tolerant:

- Morphine immediate-release tablets: Initial dose: 15 to 30 mg orally every 4 hours as needed to manage pain

- Morphine immediate-release oral solution: Initial dose: 10 to 20 mg orally every 4 hours as needed to manage pain

Titration and maintenance: Individually titrate to a dose that provides an appropriate balance between pain management and opioid-related adverse reactions

IMPORTANT NOTE: Oral solution is available in 3 concentrations 2 mg/mL, 4 mg/mL, and 20 mg/mL; reserve use of 20 mg/mL concentration for patients who are opioid-tolerant

Parenteral morphine

- Intravenous (IV): 0.1 mg to 0.2 mg/kg via slow IV injection every 4 hours as needed to manage pain; alternatively, 2 to 10 mg IV (based on 70 kg adult)

- Intramuscular (IM): 10 mg IM every 4 hours as needed to manage pain (based on 70 kg adult)

Titration and maintenance: Individually titrate to a dose that provides an appropriate balance between pain management and opioid-related adverse reactions

IMPORTANT NOTE: Intramuscular (IM) administration is not the recommended route of administration due to its painful administration, wide fluctuations in muscle absorption, 30 to 60-minute lag to peak effect, and rapid fall off of action compared to oral administration

Conversion from Parenteral to Oral Morphine

Between 3 and 6 mg of oral morphine provides pain relief equivalent to 1 mg of parenteral morphine

Morphine Patient-Controlled Analgesia (PCA)

Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) is a type of pain management that uses a computerized pump attached to the intravenous (IV) line and the pain medicine is given through the pump through an IV line placed into your vein. Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) lets you decide by pressing a handheld button when you will get a dose of pain medicine.

Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) can be used in the hospital to ease pain after surgery. Or it can be used for painful conditions like pancreatitis or sickle cell disease. It also works well for people who can’t take medicines by mouth. Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) can also be used at home by people who are in hospice or who have moderate to severe pain caused by cancer. Children as young as age 7 can benefit from patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) if they understand the idea behind it, can follow instructions, and are closely monitored. However, patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) is not advised for people who are confused, disoriented, or unresponsive.

For use in a compatible infusion device; patient must be closely monitored because of the considerable variability in both dose requirements and patient response. Mean morphine self-administration rate during clinical trials was 1 to 10 mg/hour during clinical trials. The following is provided as guidance; doses should be individualized:

- Loading dose: 2.5 mg

- Demand dose: 0.5 to 2 mg

- Lockout: 10-minute

Maximum dosing:

- Opioid Naive: 10 mg/hour;

- Opioid Tolerant: 30 mg/hour, although greater rates may be needed in select patients

Morphine Epidural administration

- Initial dose: 5 mg in the lumbar region may provide satisfactory pain relief for up to 24 hours

- If adequate pain relief is not achieved within 1-hour, doses of 1 to 2 mg may be given at intervals sufficient to assess effectiveness

- Maximum dose: 10 mg per 24 hours

Morphine Intrathecal Administration

Morphine dosage is usually one-tenth that of epidural dosage.

- Initial dose: 0.2 to 1 mg may provide satisfactory pain relief for up to 24 hours

- Repeated intrathecal injections are not recommended

- A constant intravenous infusion of naloxone 0.6 mg/hr for 24 hours may be used to reduce the incidence of potential side effects

Adult Dose for Chronic Pain

For the management of pain severe enough to require daily, around-the-clock, long-term opioid treatment and for which alternative treatment options are inadequate. Individualize dosing regimen taking into account severity of pain, response to therapy, prior analgesic treatment experience, and risk factors for addiction, abuse, and misuse: A single dose greater than 60 mg, a total daily dose greater than 120 mg, and the 20 mg/mL oral solution should be restricted to use in opioid-tolerant patients only.

Comments:

- Monitor closely for respiratory depression, especially within the first 24 to 72 hours of initiating therapy and with all dose increases.

- Use of higher starting doses in patients who are not opioid tolerant may cause fatal respiratory depression with first dose; initial dose selection should take into account degree of opioid tolerance, patient’s general condition, medical status, concurrent medications, type and severity of pain, and risk factors for abuse, addiction, or diversion.

- Opioid tolerant patients are those who have received for 1 week or longer: oral morphine 60 mg/day; transdermal fentanyl 25 mcg/hr; oral oxycodone 30 mg/day; oral hydromorphone 8 mg/day; oral oxymorphone 25 mg/day or an equianalgesic dose of another opioid.

- Extended-release (ER) products are reserved for use in patients for whom alternative treatment options (e.g., non-opioid analgesics or immediate-release [IR] opioids) are ineffective, not tolerated, or would be otherwise inadequate to provide sufficient management of pain; these products are not intended to be used as as-needed (PRN) analgesics.

Oral morphine immediate-release (IR)

- Opioid-Naive and Opioid Non-tolerant:

- Morphine immediate-release tablets: Initial dose: 15 to 30 mg orally every 4 hours

- Morphine immediate-release oral solution: Initial dose: 10 to 20 mg orally every 4 hours

Titration and maintenance: Individually titrate to a dose that provides an appropriate balance between pain management and opioid-related adverse reactions; when using immediate release (IR) formulations for chronic pain, doses should be scheduled around the clock, or consider switching to an extended release (ER) formulation

Conversion of Immediate-Release (IR) to Extended-Release (ER): At a given dose, the same total amount of morphine is available from an immediate release (IR) and extended release (ER) formulation, however, conversion to an equivalent daily dose of an extended release (ER) formulation could lead to excessive sedation at peak serum levels; monitor closely for signs of excessive sedation and respiratory depression.

Oral morphine extended-release (ER)

- Morphine Extended-Release (ER) Tablets (OPIOID-NAIVE and OPIOID NON-TOLERANT): Initial dose: 15 mg orally every 8 or 12 hours

- Morphine Extended-Release (ER) Capsules (OPIOID NAIVE): Begin treatment with an immediate-release morphine

- Morphine Extended-Release (ER) Capsules (OPIOID NON-TOLERANT): Initial dose: 30 mg orally every 24 hours

Titration and maintenance: Adjust dose every 1 to 2 days as needed to obtain an appropriate balance between pain management and opioid-related adverse reactions; for patients experiencing inadequate analgesia with once a day extended release (ER) capsules or twice a day extended release (ER) tablets, may consider increasing dose frequency to every 12 hours for extended release (ER) capsules or every 8 hours for extended release (ER) tablets; goal should be to find the lowest effective dosage for the shortest duration consistent with individual patient treatment goals.

IMPORTANT NOTES:

- Parenteral to Oral Morphine Ratio: 1 mg parenteral morphine provides analgesia equivalent to between 2 and 6 mg of oral morphine

- Extended release (ER) formulations are not bioequivalent and therefore, not interchangeable.

- Discontinue all other around-the-clock opioid drugs when initiating extended release (ER) morphine

- Opioid equivalent tables will be helpful to guide conversion, but it should be understood that wide inter-patient variability in the potency of opioid drugs and formulations is not accounted for in these tables; conversions should be done carefully and with close monitoring for signs and symptoms of opioid withdrawal, over sedation, and overdose.

- When converting between different opioids or different formulations, it is safer to underestimate the 24-hour dose and provide rescue medication than to overestimate and manage an overdose.

Morphine suppository

- Usual Adult Dose: 10 to 20 mg rectally every 4 hours

- Dose should be individualized.

Neuraxial drug administration

Neuraxial drug administration describes techniques that deliver drugs in close proximity to the spinal cord, i.e. intrathecally into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or epidurally into the fatty tissues surrounding the dura, by injection or infusion. Neuraxial morphine administration is for the management of pain severe enough to require opioid analgesia by epidural or intrathecal management without attendant loss of motor, sensory, or sympathetic function. Patients must be observed in a fully equipped and staffed environment for at least 24 hours after each test dose and, as appropriate, for the first several days after catheter implantation.

Uses:

- Duramorph (morphine injection) is NOT for use in continuous microinfusion devices

- Infumorph (morphine sulfate injection) is morphine pain reliever indicated only for intrathecal or epidural infusion in the treatment of intractable chronic pain. Infumorph is for use in continuous microinfusion devices and not for single-dose injection because it is too concentrated.

Dose must be individualized based upon in-hospital evaluation

- For Epidural Administration: Initial dose: 3.5 to 7.5 mg/day (opioid non-tolerant) or 4.5 to 10 mg/day (some degree of opioid tolerance); dose requirements may increase significantly during treatment; daily dose limit for each patient must be individualized

- For Intrathecal Administration: Initial dose: 0.2 to 1 mg/day (opioid non-tolerant) or 1 to 10 mg/day (some degree of opioid tolerance); daily dose limit for each patient must be individualized.

NOTE: Intrathecal dose is usually one-tenth that of epidural dose

Children Dose for Pain

The safety and efficacy of morphine in patients younger than 18 years have not been established, however, morphine is used in clinical practice. The following should be considered guidance (off-label use):

- Less than 6 months (not mechanically ventilated): Initial dose: 0.025 to 0.03 mg/kg IV or 0.075 to 0.09 mg/kg orally every 4 to 6 hours as needed to manage pain

- 6 months or older, weight less than 45 kg: 0.1 mg/kg IV or 0.3 mg/kg orally every 4 to 6 hours as needed to manage pain

- 6 months or older, weight 45 kg or more:

- Immediate-release tablets: Initial dose: 15 to 30 mg orally every 4 hours as needed to manage pain

- Immediate-release oral solution: Initial dose: 10 to 20 mg orally every 4 hours as needed to manage pain

Titration and maintenance: Individually titrate to a dose that provides an appropriate balance between pain management and opioid-related adverse reactions.

Morphine Patient-Controlled Analgesia (PCA)

Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) is a type of pain management that uses a computerized pump attached to the intravenous (IV) line and the pain medicine is given through the pump through an IV line placed into your vein. Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) lets you decide by pressing a handheld button when you will get a dose of pain medicine.

Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) can be used in the hospital to ease pain after surgery. Or it can be used for painful conditions like pancreatitis or sickle cell disease. It also works well for people who can’t take medicines by mouth. Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) can also be used at home by people who are in hospice or who have moderate to severe pain caused by cancer. Children as young as age 7 can benefit from patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) if they understand the idea behind it, can follow instructions, and are closely monitored. However, patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) is not advised for people who are confused, disoriented, or unresponsive.

Children should demonstrate the ability to use patient-controlled analgesia (PCA): most 7-year olds are able to use the PCA device correctly.

For use in a compatible infusion device; patient must be closely monitored because of the considerable variability in both dose requirements and patient response. Mean morphine self-administration rate during clinical trials was 1 to 10 mg/hour during clinical trials.

The following is provided as guidance; doses should be individualized:

- Loading dose: 2.5 mg

- Demand dose: 0.5 to 2 mg

- Lockout: 10-minute

Maximum Dosing:

- Opioid Naive: 10 mg/hour;

- Opioid Tolerant: 30 mg/hour, although greater rates may be needed in select patients

For pediatric patients older than 6 months, the clinical effects and pharmacokinetics of opioids are similar to adults; however, there is limited evidence regarding the long-term neurocognitive effects of short-term opioid analgesic use.

Children Dose for Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome

For the pharmacologic treatment of neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) in accordance with treatment protocols developed by neonatology experts. The optimal treatment approach for managing neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) continues to be investigated; pharmacologic management often includes morphine. The following should be considered guidance (off-label use) as other protocols may be as effective.

Comments:

- Approximately 60% to 80% of neonates with neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) may not respond to non-pharmacologic treatment and will require medication.

- Pharmacologic treatment is initiated/titrated/weaned as part of an overall treatment strategy based on neonatal abstinence scores (e, g. Finnegan scores).

- The Finnegan scoring system has been standardized for use in term infants; its use in preterm or older infants should be considered not standardized; additionally, significant intra-observer variability has been documented.

Weight-based dosing

- Initial dose: 0.04 mg/kg orally every 3 to 4 hours

- Titrate in increments of 0.04 mg/kg/dose

- Maximum dose: 0.2 mg/kg.

Symptom-based dosing (Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome [NAS] Score)

- NAS Score 9 to 12: Dose: 0.04 mg orally every 4 hours

- NAS Score 13 to 16: Dose: 0.08 mg orally every 4 hours

- NAS Score 17 to 20: Dose: 0.12 mg orally every 4 hours

- NAS Score 21 to 24: Dose: 0.16 mg orally every 4 hours

- NAS Score greater than 25: Dose: 0.2 mg orally every 4 hours

WEANING: After 48 hours of Clinical Stability

- Reduce dose by 10% every 24 to 48 hours

- Cease therapy when dose is 0.15 mg/kg/day

Dose Adjustments

- Elderly: Due to increased sensitivity to drug effects, start at the lower end of the dosing range, titrate slowly, and closely monitor

- Debilitated patients, and patients with impaired respiratory function: May need to reduce dose initial dose by up to one-half, titrate slowly, and closely monitor

- Dosage reductions may be required with concomitant central nervous system depressant therapy

- Appropriate precaution is necessary if used for postoperative pain; as with all opioids, extreme caution is needed following abdominal surgery.

Kidney Dose Adjustments

Use with caution; start with a lower initial dose, titrate slowly, and monitor closely.

Dialysis: Data not available

Liver Dose Adjustments

Use with caution; start with a lower initial dose, titrate slowly, and monitor closely.

Monitoring

- Cardiovascular: Monitor for signs of hypotension upon initiating therapy and following dose increases, especially those whose blood pressure is compromised

- Respiratory: Monitor for respiratory depression, especially within the first 24 to 72 hours of initiation and with dose increases.

- Gastrointestinal: Monitor for constipation and decreased bowel motility

- General: Monitor routinely for maintenance of pain control and incidence of adverse reactions.

- Psychiatric: Patients should be monitored for the development of addiction, abuse, or misuse.

Discontinuation

- Gradually withdraw dose in the physically dependent patient.

- Taper dose by 25% to 50% every 2 to 4 days, while monitoring for signs and symptoms of withdrawal.

- If signs or symptoms of withdrawal develop, raise the dose to the previous level and taper more slowly.

Morphine side effects

Common morphine side effects include:

- constipation

- feeling confused

- generally feeling unwell

- drowsiness

- headaches

- dizziness

- tiredness

- extreme tiredness and weakness

- anxiety

- nausea

- vomiting

- stomach pain

- sudden jerking of the body due to muscle contractions

- gas

- sweating

- shortness of breath

- low oxygen levels (hypoxia)

- feeling light-headed

- feelings of extreme happiness or sadness

- mood changes

- difficulty urinating

- loss of appetite

- rash or itchy skin

- difficulty sleeping (insomnia).

Some morphine side effects can be serious. If you experience any of these symptoms, see your doctor immediately or get emergency medical treatment:

- seizures

- slowed breathing

- long pauses between breaths

- shortness of breath

- symptoms of serotonin syndrome, such as: agitation, hallucinations (seeing things or hearing voices that do not exist), fever, sweating, shivering, fast heart rate, muscle stiffness, twitching, loss of coordination, nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea

- nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, weakness, or dizziness

- inability to get or keep an erection

- irregular menstruation

- decreased sexual desire

- hives; rash; itching; swelling of the eyes, face, mouth, lips or throat; hoarseness; difficulty breathing or swallowing

Morphine may cause other side effects. See your doctor if you have any unusual problems while you are using morphine.

Morphine withdrawal

As with some other drugs, a person can build up a tolerance to morphine. Tolerance means users need more and more morphine to have the same effect. After only a short time, the person using morphine will need to take larger doses to achieve the same effect. Soon their body will start to depend on morphine in order to function ‘normally’. For some people who are dependent on morphine, nothing else in life matters except the morphine. A person who is dependent on morphine may ignore his or her career, relationships and even basic needs like eating. Financial, legal and other personal problems may be related to morphine use. If someone who is dependent on morphine stops using it, they have withdrawal symptoms. These symptoms can include restlessness, muscle and bone pain, diarrhea, vomiting, and cold flashes with goose bumps. The person craves the morphine and this psychological dependence makes him or her panic if he or she cannot have it, even temporarily.

Repeated use of morphine often leads to morphine use disorder, sometimes called morphine addiction. Morphine addiction is more than physical dependence. Morphine addiction is a long-lasting brain disorder. When someone has it, they continue to use morphine even though it causes problems in their life. Some examples include health problems and not being able to meet responsibilities at work, school, or home. Getting and using morphine becomes their main purpose in life.

Withdrawal from morphine can occur any time long-term use is stopped or cut back.

Early symptoms of morphine withdrawal include:

- Agitation

- Anxiety

- Muscle aches

- Increased tearing

- Insomnia

- Runny nose

- Sweating

- Yawning

Late symptoms of morphine withdrawal include:

- Abdominal cramping

- Diarrhea

- Dilated pupils

- Goosebumps

- Nausea

- Vomiting

These symptoms are very uncomfortable but are not life threatening. Symptoms usually start within 12 hours of last morphine usage and within 30 hours of last methadone exposure.

Withdrawal from either opiates or opioids on your own can be very hard and may be dangerous. Treatment most often involves medicines, counseling, and support and is the same for both opiates and opioids. You and your doctor will discuss your care and treatment goals.

Withdrawal can take place in a number of settings:

- At-home, using medicines and a strong support system. (This method is difficult, and withdrawal should be done very slowly.)

- Using facilities set up to help people with detoxification (detox).

- In a regular hospital, if symptoms are severe.

Morphine Addiction

Addiction to morphine develops for a number of reasons and is often the consequence of consistent abuse. An addiction typically begins with a tolerance — needing larger doses of morphine to feel its effects. Once a tolerance develops, users will experience withdrawal symptoms when they don’t take morphine, making it hard to quit. In many cases, the psychological dependence on morphine develops soon after the physical one.

Someone addicted to morphine will compulsively look for and and abuse it, ignoring the negative consequences. Morphine addiction is similar to heroin addiction and is a very difficult addiction to overcome. Sudden withdrawal from morphine can be extremely uncomfortable and unpleasant; therefore, a medically managed detoxification is the best way to rid the body of the substance. Contact your doctor to discuss available treatment options.

Treatment for morphine addiction

A variety of effective treatments are available for morphine addiction, including medicines to treat withdrawal symptoms, medicine to block the effects of opioids, and behavioral treatments. Often, a combination of medicine and behavioral treatment works best to restore a degree of normalcy to brain function and behavior, resulting in increased employment rates and lower risk of HIV and other diseases and criminal behavior. Although behavioral and medicine treatments can be extremely useful when utilized alone, research shows that for many people, integrating both types of treatments is the most effective approach.

Treatment options for morphine addiction include 23:

- Medications for opioid use disorder. The medicines used to treat opioid misuse and addiction are methadone (long-acting opioid), buprenorphine or naltrexone.

- Counseling and behavioral therapies.

- Medication-assisted therapy (MAT), which includes medication for opioid addiction, counseling, and behavioral therapies. This offers a “whole patient” approach to treatment, which can increase your chance of a successful recovery.

- Residential and hospital-based treatment.

- Residential programs combine housing and treatment services. You are living with your peers, and you can support each other to stay in recovery.

- Inpatient hospital-based programs combine health care and addiction treatment services for people with medical problems. Hospitals may also offer intensive outpatient treatment. All these types of treatments are very structured, and usually include several different kinds of counseling and behavioral therapies. They also often include medicines.

- To date, the most effective form of treatment for a morphine addiction is an inpatient program, usually lasting around 90 days. One of the potential benefits of inpatient rehab is that it typically starts with a safe, medically supervised detox. Inpatient programs allow a recovering addict to focus on treatment without the social and professional pressures of the world outside.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved opioid use disorder medications for the treatment of opioid use disorder include buprenorphine (often combined with naloxone), methadone, and naltrexone.

- Buprenorphine

- Partial mu-opioid receptor agonist.

- Suppresses and reduces cravings for opioids.

- Can be prescribed by any clinician with a current, standard Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) registration with Schedule 3 authority, in any clinical setting.

- The following buprenorphine products are FDA approved for the treatment of opioid use disorder:

- Generic Buprenorphine/naloxone sublingual tablets

- Buprenorphine sublingual tablets (Subutex)

- Buprenorphine/naloxone sublingual films (Suboxone)

- Buprenorphine/naloxone) sublingual tablets (Zubsolv)

- Buprenorphine/naloxone buccal film (Bunavail)

- Buprenorphine implants (Probuphine)

- Buprenorphine extended-release injection (Sublocade)

- Methadone

- Full mu-opioid receptor agonist.

- Reduces opioid cravings and withdrawal and blunts or blocks the effects of opioids.

- Can only be provided for opioid use disorder through a Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)-certified opioid treatment program (https://dpt2.samhsa.gov/treatment/directory.aspx)

- Naltrexone

- Opioid receptor antagonist.

- Blocks the euphoric and sedative effects of opioids and prevents feelings of euphoria.

- Should be started after a minimum of 7 to 10 days free of opioids to avoid precipitation of severe opioid withdrawal.

- Can be prescribed by any clinician with an active license to prescribe medications.

People getting treatment for morphine addiction should work with their doctor to come up with a treatment plan that fits their needs.

Morphine overdose

Morphine can potentially be a deadly medication when not used properly. Morphine overdose occurs when a person intentionally or accidentally takes too much of morphine. It causes a host of symptoms related to depression of the central nervous system. Severe breathing depression is the most feared complication of morphine in cases of an overdose. Immediate injection of naloxone is required to reverse the effects of morphine.

Morphine overdose may include the following signs and symptoms:

- slow, shallow, or irregular breathing

- difficulty breathing

- excessive sleepiness

- extreme drowsiness

- unable to respond or wake up (decreased awareness or responsiveness)

- limp or weak muscles

- cold, clammy skin

- constricted, pinpoint, or small pupils (black part of the eye)

- slow heartbeat

- unusual snoring.

While using morphine injection, you should talk to your doctor about having a rescue medication called naloxone readily available (e.g., home, office). Naloxone is used to reverse the life-threatening effects of an opioid overdose. Naloxone works by blocking the effects of opiates to relieve dangerous symptoms caused by high levels of opiates in the blood. Your doctor may also prescribe you naloxone if you are living in a household where there are small children or someone who has abused street or prescription drugs. Ask your doctor about other ways that you can obtain naloxone (directly from a pharmacy or as part of a community based program). You should make sure that you and your family members, caregivers, or the people who spend time with you know how to recognize an overdose, how to use naloxone, and what to do until emergency medical help arrives. Your doctor or pharmacist will show you and your family members how to use naloxone. Ask your pharmacist for the instructions or visit the manufacturer’s website to get the instructions. If symptoms of a morphine overdose occur, a friend or family member should give the first dose of naloxone, call your local emergency number immediately, and stay with you and watch you closely until emergency medical help arrives. Your symptoms may return within a few minutes after you receive naloxone. If your symptoms return, the person should give you another dose of naloxone. Additional doses may be given every 2 to 3 minutes, if symptoms return before medical help arrives.

Naloxone

Naloxone is a US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved medicine used to quickly reverse an opioid or narcotic overdose 24. Naloxone is available as a nasal spray (Narcan 4mg, Kloxxado 8mg) or an injection (Zimhi 5 mg/0.5 mL). Naloxone is a opioid antagonist that works by attaching to opioid receptors and therefore reverses and blocks the effects of other opioids. Naloxone can quickly restore normal breathing to a person if their breathing has slowed or stopped because of an opioid overdose. But, naloxone has no effect on someone who does not have opioids in their system, and it is not a treatment for opioid use disorder. Examples of opioids sometimes called narcotics are buprenorphine, heroin, fentanyl, oxycodone (OxyContin), hydrocodone (Vicodin, Lortab), codeine, morphine, hydromorphone, meperidine, methadone, oxymorphone, and tramadol. There are no age restrictions on the use of naloxone; it can be used for suspected overdose in infants and children through elderly people. Naloxone saves lives. From 1996 to 2014, at least 26,500 opioid overdoses in the United States were reversed by laypersons using naloxone. Naloxone does not cause physical or psychological dependence and has virtually no effect in a healthy non-dependent person 25.

Naloxone should be used as soon as possible to treat a known or suspected opioid overdose emergency, if there are signs of slowed breathing, severe sleepiness or the person is not able to respond (loss of consciousness) 26. Once naloxone has been given the patient must receive emergency medical care straight away, even if they wake up.

First, recognize signs of an opioid overdose:

- Limp body

- Pale, clammy face

- Blue lips, gums or fingertips

- Vomiting or gurgling sounds

- Inability to speak or be awakened

- Slow and shallow breathing

- Slow or irregular heartbeat or pulse

- Small pupils

- Vomiting

- Unresponsiveness (doesn’t wake up when shaken or called)

- Unconsciousness

If you see these symptoms, call your local emergency services number immediately and consider the use of naloxone if available. If the person has stopped breathing or if breathing is very weak, begin CPR (best performed by someone who has training).

Naloxone is a prescription medicine but in many states, naloxone is available from a pharmacist without a prescription from your doctor, under state Naloxone Access Laws or alternate arrangements. Furthermore, naloxone is not a controlled substance, according to the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).

Naloxone works to reverse opioid overdose in the body for only 30 to 90 minutes. But many opioids remain in the body longer than that. Because of this, it is possible for a person to still experience the effects of an overdose after a dose of naloxone wears off. Also, some opioids are stronger and might require multiple doses of naloxone. Therefore, one of the most important steps to take is to call your local emergency services number for an ambulance so the individual can receive immediate medical attention.

People who are given naloxone should be observed constantly until emergency care arrives. They should be monitored for another 2 hours after the last dose of naloxone is given to make sure breathing does not slow or stop.

People with physical dependence on opioids may have opioid withdrawal symptoms within minutes after they are given naloxone.

Opioid withdrawal symptoms might include:

- headaches,

- changes in blood pressure,

- rapid heart rate,

- sweating,

- nausea,

- vomiting,

- feeling nervous, restless, or irritable

- tremors.

- body aches

- dizziness or weakness

- diarrhea, stomach pain, or nausea

- fever, chills, or goose bumps

- sneezing or runny nose in the absence of a cold

While this is uncomfortable, it is usually not life threatening. The risk of death for someone overdosing on opioids is worse than the risk of having a bad reaction to naloxone.

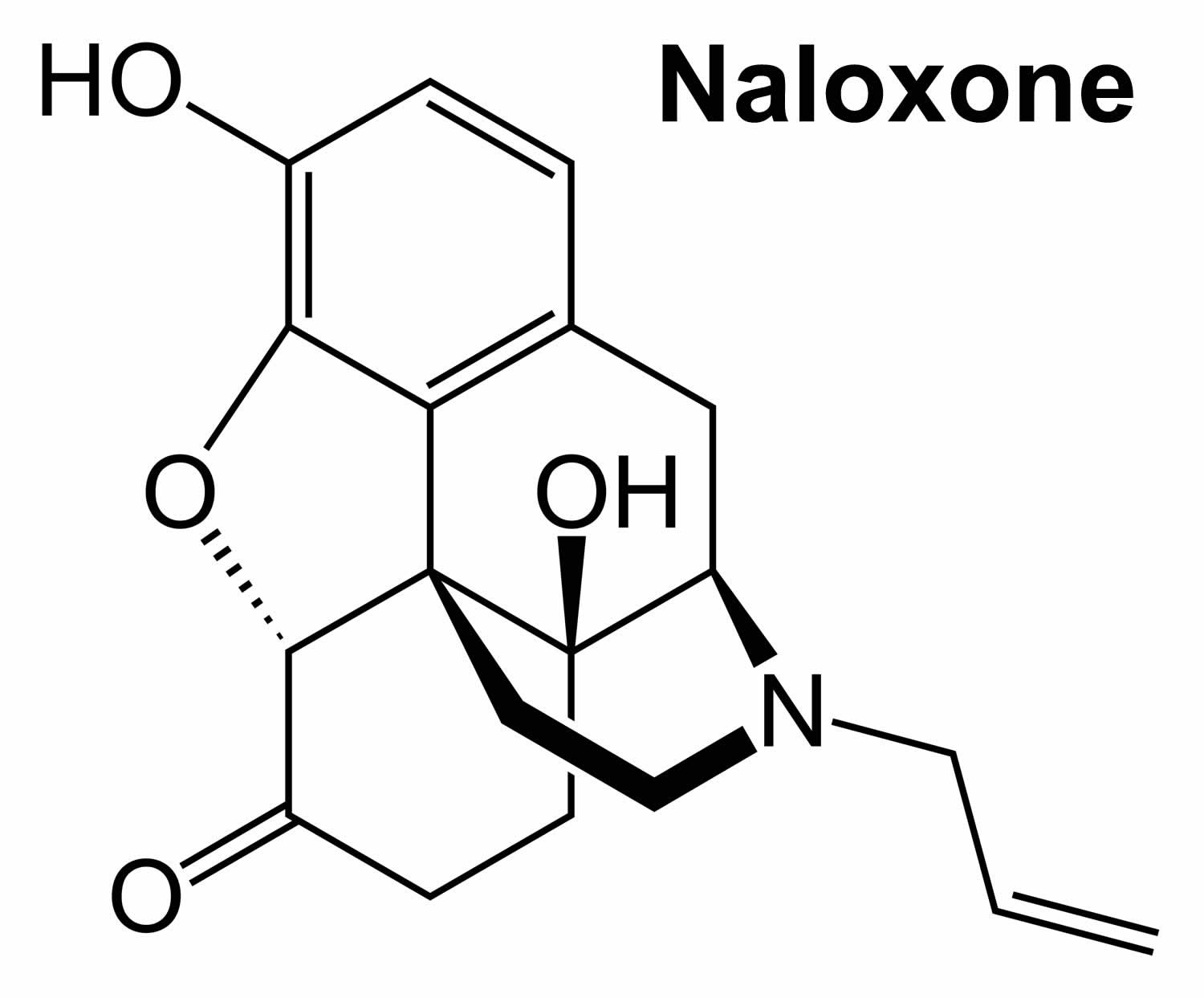

Figure 2. Naloxone chemical structure

How to use and give naloxone

Home preparations include a naloxone nasal spray (Narcan 4mg, Kloxxado 8mg) given to someone while they lie on their back or a device that automatically injects naloxone (Zimhi 5 mg/0.5 mL) into the thigh. Sometimes more than one dose is needed. You may need another naloxone injection every 2 to 3 minutes until emergency help arrives.

The person’s breathing also needs to be monitored. If the person stops breathing, consider rescue breaths and CPR if you are trained until first responders arrive.

Naloxone works to reverse opioid overdose in the body for only 30 to 90 minutes. But many opioids remain in the body longer than that. Because of this, it is possible for a person to still experience the effects of an overdose after a dose of naloxone wears off. Also, some opioids are stronger and might require multiple doses of naloxone. Therefore, one of the most important steps to take is to call your local emergency services number for an ambulance so the individual can receive immediate medical attention.

People who are given naloxone should be observed constantly until emergency care arrives. They should be monitored for another 2 hours after the last dose of naloxone is given to make sure breathing does not slow or stop.

People with physical dependence on opioids may have withdrawal symptoms within minutes after they are given naloxone. Withdrawal symptoms might include headaches, changes in blood pressure, rapid heart rate, sweating, nausea, vomiting, and tremors. While this is uncomfortable, it is usually not life threatening. The risk of death for someone overdosing on opioids is worse than the risk of having a bad reaction to naloxone.

Naloxone injection instructions

- Each naloxone injection contains only one dose of medicine and cannot be reused.

- Place the patient on their back and when you are ready to inject, pull off cap to expose needle.

- Do not put your finger on top of the device. For a child under the age of 1 years old, pinch the thigh muscle while administering the dose.

- Hold naloxone injection by finger grips only and slowly insert the needle into the thigh.

- After needle is in thigh you should push the plunger all the way down until it clicks and then hold for 2 seconds.

- Right after the injection, using one hand with fingers behind the needle, slide the safety guard over the needle. You should not use two hands to activate the safety guard. Put the used syringe into the blue case and close the case.

Naloxone nasal spray instructions

To give naloxone nasal spray, follow these steps:

- Lay the person on their back to give the medication. Support their neck with your hand and allow the head to tilt back before giving the nasal spray.

- Remove the naloxone nasal spray from the box. Peel back the tab to open the spray.

- Do not prime the nasal spray before using it.

- Hold the naloxone nasal spray with your thumb on the bottom of the plunger and your first and middle fingers on either side of the nozzle.

- Gently insert the tip of the nozzle into one nostril, until your fingers on either side of the nozzle are against the bottom of the person’s nose. Provide support to the back of the person’s neck with your hand to allow the head to tilt back.

- Press the plunger firmly to release the medication.

- Remove the nasal spray nozzle from the nostril after giving the medication.

- Turn the person on their side (recovery position) and call for emergency medical assistance immediately after giving the first naloxone dose.

- If the person does not respond by waking up, to voice or touch, or breathing normally or responds and then relapses, give another dose. If needed, give additional doses (repeating steps 2 through 7) every 2 to 3 minutes in alternate nostrils with a new nasal spray each time until emergency medical assistance arrives.

- Put the used nasal spray(s) back in the container and out of reach of children until you can safely dispose of it.

Ask your pharmacist or doctor for a copy of the manufacturer’s information for the patient.

After giving a dose of naloxone

- You need to get emergency medical help as soon as you have given the injection or nasal spray.

- Tell the healthcare provider that you have given a dose of naloxone.

- Turn the patient on their side to place them in the recovery position after giving them the naloxone.

- If symptoms continue or return after using the naloxone, an additional dose may be needed.

- If you are giving additional doses, use a new naloxone nasal spray or new naloxone injection every 2 to 3 minutes and continue to closely watch the person until emergency help has arrived.

- You may need to perform CPR (cardiopulmonary resuscitation) on the person while you are waiting for emergency help to arrive.

- Using naloxone does not take the place of emergency medical care.

Figure 3. Recovery position

How is naloxone given?

Naloxone should be given to any person who shows signs of an opioid overdose or when an opioid overdose is suspected. Naloxone can be given as a nasal spray (Narcan 4mg, Kloxxado 8mg) or it can be injected (Zimhi 5 mg/0.5 mL) into the muscle, under the skin, or into the veins. Sometimes more than one dose is needed. You may need another naloxone injection every 2 to 3 minutes until emergency help arrives.

The person’s breathing also needs to be monitored. If the person stops breathing, consider rescue breaths and CPR if you are trained until first responders arrive.

Naloxone works to reverse opioid overdose in the body for only 30 to 90 minutes. But many opioids remain in the body longer than that. Because of this, it is possible for a person to still experience the effects of an overdose after a dose of naloxone wears off. Also, some opioids are stronger and might require multiple doses of naloxone. Therefore, one of the most important steps to take is to call your local emergency services number for an ambulance so the individual can receive immediate medical attention.

People who are given naloxone should be observed constantly until emergency care arrives. They should be monitored for another 2 hours after the last dose of naloxone is given to make sure breathing does not slow or stop.

People with physical dependence on opioids may have withdrawal symptoms within minutes after they are given naloxone. Withdrawal symptoms might include headaches, changes in blood pressure, rapid heart rate, sweating, nausea, vomiting, and tremors. While this is uncomfortable, it is usually not life threatening. The risk of death for someone overdosing on opioids is worse than the risk of having a bad reaction to naloxone.

What if I’m not sure if someone has an opioid overdose?

Giving someone naloxone, who is suspected to have an opioid overdose, in an emergency won’t hurt them, but it could save their life! Naloxone will not harm someone who does not have opioids in their system. Naloxone is a opioid antagonist that works in the brain only at the opioid receptor, binding to the receptors and blocking the opioids and the effects of opioids. If someone is having a different medical emergency – such as a diabetic coma or cardiac arrest – and you give them naloxone, the drug won’t have any effect or harm them.

Naloxone is being used more by police officers, emergency medical technicians, and non-emergency first responders than before. In most states, people who are at risk or who know someone at risk for an opioid overdose can be trained on how to give naloxone. Families can ask their pharmacists or health care provider how to use the naloxone devices.

Is naloxone safe?

Yes. There is no evidence of significant adverse reactions to naloxone 27. Administering naloxone in cases of opioid overdose can cause withdrawal symptoms when the person is dependent on opioids; this is uncomfortable without being life threatening 28, 29. The risk that someone overdosing on opioids will have a serious adverse reaction to naloxone is far less than their risk of dying from overdose 30, 31, 32, 33. Naloxone works if a person has opioids in their system and has no harmful effect if opioids are absent. Naloxone should be given to any person who shows signs of an opioid overdose or when an opioid overdose is suspected 34.

What are the different types of naloxone?

Naloxone comes in two FDA-approved forms: injectable naloxone (Zimhi 5 mg/0.5 mL) and prepackaged nasal spray naloxone (Narcan 4mg, Kloxxado 8mg). No matter what dosage form you use, it’s important to receive training on how and when to use naloxone. You should also read the product instructions and check the expiration date.