Contents

- Heroin

- Heroin mechanism of action

- Heroin and pregnancy

- Heroin dependence and addiction

- Heroin withdrawal

- Heroin overdose

- Naloxone

- How to use and give naloxone

- Naloxone injection instructions

- Naloxone nasal spray instructions

- After giving a dose of naloxone

- How is naloxone given?

- What if I’m not sure if someone has an opioid overdose?

- Is naloxone safe?

- What are the different types of naloxone?

- Is there a preferable naloxone delivery system?

- Where can I get naloxone?

- How much does naloxone cost?

- How does naloxone work?

- Naloxone

Heroin

Heroin also known as diacetylmorphine, diamorphine, ‘smack’, ‘gear’, ‘horse’, ‘big H’, ‘junk’, ‘TNT’ or ‘hammer’ is an illegal and very addictive opioid drug, a depressant drug that is made from morphine, which slows down certain functions of your brain and nervous system 1. Heroin comes from the sap of the opium poppy plants (Papaver somniferum). The opium poppy plants grow in Southeast and Southwest Asia, Mexico, and Colombia. Heroin can be a white or brown powder, or a black sticky substance known as black tar heroin. Heroin is highly addictive and people who use heroin can become dependent and experience cravings. Heroin is one of the most commonly used drugs among those who misuse intravenous drugs. Heroin initial effects include feelings of well-being and relief from physical pain. With increased heroin usage, there is a corresponding increase in heroin overdose-related deaths, because heroin dealers usually ‘mix’ or ‘cut’ heroin with other substances such as sugar, starch, powdered milk, acetaminophen (paracetamol), quinine, fentanyl or caffeine to boost their profits 2. This means that the person using heroin has no idea if the dose will be strong or weak 3, 4. Fentanyl, a prescription opioid that is 100 times more powerful than morphine, is sometimes used to cut heroin or other street drugs. It may also be made into tablets that look like prescription medication. Many overdoses have occurred because people did not know that what they were taking was contaminated with fentanyl.

Heroin generally comes in the form of granules or powder, and can range in color from white to brown. Pure heroin is a white powder with a bitter taste that predominantly originates in South America and, to a lesser extent, from Southeast Asia, and dominates U.S. markets east of the Mississippi River 5. “Black tar” heroin is sticky like roofing tar or hard like coal and is predominantly produced in Mexico and sold in U.S. areas west of the Mississippi River 5. The dark color associated with black tar heroin results from crude processing methods that leave behind impurities. Users generally inject it intravenously (into a vein), but they can also sniff, snort or smoke heroin. Some people mix heroin with crack cocaine, which is called “speedballing”. All these ways of taking heroin send it to the brain very quickly, which makes heroin highly addictive.

The effects of heroin depend on:

- Strength of the heroin dose

- Size, weight, general health and state of mind of the person taking the heroin

- Effects of other drugs and medication that the person taking the heroin might have taken at the same time or even in the last two days. If you have taken other central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) depressants such as sleeping pills, tranquilizers, methadone or alcohol, the effects of heroin are increased. This can result in coma or even death.

People who use heroin report feeling a “rush” (a surge of pleasure). And then they may feel other effects, such as a warm flushing of their skin, dry mouth, and a heavy feeling in their arms and legs. They may also have severe itching, nausea, and vomiting. After these first effects, they will usually be drowsy for several hours, and their breathing will slow down.

Some of the immediate effects of taking heroin include:

- a rush of pleasurable feelings called a “rush” (euphoria) and relief from physical pain

- feeling sick or vomiting

- shallow breathing, drowsiness and sleepiness

- a drop in body temperature

- small (‘pinpoint’) pupils

- loss of sex drive.

People who use heroin over the long term may develop many different health and lifestyle problems. These problems could include liver, kidney, and lung disease, mental disorders, and abscesses.

People who inject heroin also risk getting infectious diseases such as various blood-borne viruses like HIV, hepatitis B and hepatitis C, and bacterial infections of the skin, bloodstream, and heart (endocarditis). They can also get collapsed veins. When a vein collapses, the blood cannot flow through it.

Using heroin on a regular basis can lead to major health and lifestyle problems including:

- collapsed veins and skin abscesses

- risk of contracting various blood-borne viruses, such as HIV, hepatitis B and hepatitis C, or blood poisoning from sharing needles and other injecting equipment, or using dirty or contaminated equipment

- chronic constipation

- increased risk of contracting pneumonia and other lung problems

- fertility problems

- disturbances of the menstrual cycle for women

- impotence for men (impotence is where a man can’t get or keep an erection firm enough for sexual intercourse)

- poor nutrition and reduced immunity

- loss of relationships, career and home as the person’s need for the drug becomes all-consuming

- damage to the blood vessels that lead to the lungs, liver, kidneys and brain due to the additives mixed with heroin

- risk of overdose.

People who use heroin daily must use every six to 12 hours to avoid symptoms of withdrawal. Repeated use of heroin can lead to tolerance. This means users need more and more of the drug to have the same effect. At higher doses over time, the body becomes dependent on heroin. If someone who is dependent on heroin stops using it, they have withdrawal symptoms. These symptoms can include restlessness, muscle and bone pain, diarrhea, vomiting, and cold flashes with goose bumps.

Repeated use of heroin often leads to heroin use disorder, sometimes called heroin addiction. This is more than physical dependence. It’s a chronic (long-lasting) brain disorder. When someone has it, they continue to use heroin even though it causes problems in their life. Some examples include health problems and not being able to meet responsibilities at work, school, or home. Getting and using heroin becomes their main purpose in life. The greatest increase in heroin use is seen in young adults aged 18-25. Among people aged 12 or older in 2021, an estimated 0.4% (or about 1.0 million people) had a heroin addiction in the past 12 months 6. In 2022, an estimated 0.3% of 8th graders, 0.2% of 10th graders, and 0.3% of 12th graders reported using heroin in the past 12 months 7.

Signs of heroin addiction include:

- using over a longer period or using more than planned

- wanting to quit or cut down, or trying unsuccessfully to quit

- spending a lot of time and effort getting, using and recovering from opioids

- experiencing cravings

- failing to fulfil responsibilities at work, school or home as a result of opioid use

- continuing to use opioids despite the negative social consequences caused by opioid use

- giving up activities that were once enjoyable

- using opioids in dangerous situations

- needing to take more of the drug to get the same effect (tolerance, a sign of physical dependence)

- feeling ill when opioid use suddenly stops (withdrawal, a sign of physical dependence)

- showing signs of opioid intoxication (e.g., nodding off, pinpoint pupils).

Once someone is dependent on heroin, stopping heroin use can be extremely difficult. People who have used heroin for a long time often report that they no longer experience any pleasure from the drug. They continue to use heroin to avoid the symptoms of withdrawal and to control their craving for the drug.

Heroin withdrawal symptoms can start after a matter of hours without a dose of heroin. Symptoms of heroin withdrawal may include:

- Alertness

- Cravings

- Diarrhea and vomiting

- Stomach cramps

- Goose bumps

- Sweating

- Bone, joint and muscle pain and twitching

- Dilated pupils

- Mood swings and crying

- Insomnia

- Yawning

Heroin withdrawal symptoms are not life-threatening, like alcohol or benzodiazepine withdrawal 8. Some or all of these symptoms may be seen; the patient does not need all to be diagnosed with heroin withdrawal 8.

One of the most dangerous effects of heroin use is the risk of overdose. The symptoms of heroin overdose include 9, 8:

- Dangerously low body temperature

- Slowed breathing

- Blue lips, gums or fingertips

- Limp body

- Pale, cold, clammy face and skin

- Vomiting or gurgling sounds

- Inability to speak or be awakened

- Slow and shallow breathing

- Slow or irregular heartbeat or pulse

- Small pupils

- Vomiting

- Unresponsiveness (doesn’t wake up when shaken or called)

- Unconsciousness

- Convulsions and coma.

Heroin overdose is a dangerous and deadly consequence of heroin use. A large dose of heroin depresses heart rate and breathing to such an extent that a user cannot survive without medical help. Heroin overdose danger is primarily due to hypoxia from hypoventilation (breathing at an abnormally slow rate, resulting in an increased amount of carbon dioxide in the blood), making airway management and adequate oxygenation the mainstay of therapy in the heroin overdose patient. Many deaths are caused by heroin overdoses throughout the world each year. In 2021, approximately 9,173 Americans died from a heroin overdose 10, 11, 12.

A medicine called naloxone (e.g., Narcan®, Kloxxado®) can treat a heroin or other opioid overdose if it is given in time 13. Naloxone is a opioid antagonist that works by attaching to opioid receptors and therefore reverses and blocks the effects of other opioids. Naloxone can quickly restore normal breathing to a person if their breathing has slowed or stopped because of an opioid overdose. But, naloxone has no effect on someone who does not have opioids in their system, and it is not a treatment for opioid use disorder. Sometimes more than one dose of the medicine is needed.

There are two forms of naloxone that anyone can use without medical training: nasal spray and injectable. In April 2015, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a Narcan nasal spray that is sprayed directly into one nostril. In 2021, the FDA approved a higher dose naloxone nasal spray KLOXXADO® 14. Since Narcan® and Kloxxado® can be used by family members or caregivers, it greatly expands access to naloxone. People at risk of an overdose are encouraged to carry naloxone with them. They can buy naloxone at a pharmacy.

Naloxone that can be used by nonmedical personnel has been shown to be cost-effective and save lives 15.

Figure 1. Heroin

Figure 2. Heroin and its metabolites

Footnotes: Molecular structure of heroin and its metabolites. Schematic representation of the metabolic pathway of heroin with the sequential breakdown into the main metabolites. The involved enzimatic processes are listed in italics.

[Source 1 ]Figure 3. Effects of heroin

Heroin mechanism of action

Heroin is synthesized from morphine by acetylation at both 3 and 6 positions and broken down in the human body to active opioid compounds first by deacetylation to 6 mono acetyl morphine (6MAM) and then by further deacetylation to morphine 17, 18, 8. Heroin is a central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) depressant. This means heroin slows down your brain function and affects your breathing which can slow down or even stop. Your body temperature and blood pressure can drop, and your heartbeat can become irregular. You may lose consciousness or lapse into a coma.

6 mono acetyl morphine (6MAM) metabolite is a specific byproduct of heroin metabolism. 6 mono acetyl morphine (6MAM) is eliminated in the urine quickly and is detected for less than 8 hours after heroin abuse 19.

Heroin and/or its metabolites (substances the body produces as it processes drugs) bind to and activate opioid receptors in the brain. Recent classification scheme identifies 3 major classes of opioid receptors, with several minor classes 20, 21.. The 3 most clinically relevant opioid receptors are the mu (μ), kappa (κ), and delta (δ) opioid receptors 8. Stimulation of central mu (μ) opioid receptors causes respiratory depression, pain relieve (supraspinal and peripheral), and euphoria (a feeling or state of intense excitement, well-being and happiness) 8. Kappa (κ) and delta (δ) opioid receptors also have potent pain relieving effects, with the kappa (κ) opioid receptors being known for causing disassociation, hallucinations, and dysphoria (a state of feeling uneasy, unhappy or unwell) 8. Delta (δ) opioid receptors also modulate mu (μ) receptors and are thought to influence mood.

Heroin has effects on the mu (μ) opioid receptor. Heroin also has effects on the kappa (κ), and delta (δ) opioid receptors. Your body contain naturally occurring chemicals called neurotransmitters that bind to these receptors throughout your brain and body to regulate pain, hormone release, and feelings of well-being 21. When mu (μ) opioid receptors are activated in the reward center of your brain, they stimulate the release of the neurotransmitter dopamine, causing a reinforcement of drug taking behavior 22. The consequences of activating opioid receptors with externally administered opioids, versus naturally occurring chemicals within your body, depend on a variety of factors: how much of a drug is used, where in the brain or rest of the body they bind, how rapidly they get there, how strong and persistent is that interaction it binds, how strongly it binds and for how long, how quickly it gets there, and what happens afterward.

Once heroin enters your brain, it is converted to morphine and binds rapidly to opioid receptors 23.

Opioids act on many places in your brain and nervous system:

- Opioids can depress breathing by changing neurochemical activity in the brain stem, where automatic body functions such as breathing and heart rate are controlled.

- Opioids can reinforce drug taking behavior by altering activity in the limbic system, which controls emotions.

- Opioids can block pain messages transmitted through the spinal cord from the body.

People who use heroin typically report feeling a surge of pleasurable sensation called a “rush”. The intensity of the rush is a function of how much drug is taken and how rapidly the drug enters the brain and binds to the opioid receptors. With heroin, the rush is usually accompanied by a warm flushing of the skin, dry mouth, and a heavy feeling in the extremities. Nausea, vomiting, and severe itching may also occur. After the initial effects, users usually will be drowsy for several hours; mental function is clouded; heart function slows; and breathing is also severely slowed, sometimes enough to be life-threatening. Slowed breathing can also lead to coma and permanent brain damage 24.

Heroin has a short half-life, requiring drug users to use heroin several times per day to maintain the effect. There is an evolving body of knowledge that the intensity and quality of response to heroin and other opioids can vary significantly between patients, which can be unrelated to tolerance 25, 26.

Heroin also produces profound degrees of tolerance and physical dependence. Tolerance occurs when more and more of the drug is required to achieve the same effects. With physical dependence, the body adapts to the presence of the drug, and withdrawal symptoms occur if use is reduced abruptly.

Withdrawal may occur within a few hours after the last time the drug is taken. Symptoms of withdrawal include restlessness, muscle and bone pain, insomnia, diarrhea, vomiting, cold flashes with goose bumps (“cold turkey”), and leg movements. Major withdrawal symptoms peak between 24–48 hours after the last dose of heroin and subside after about a week. However, some people have shown persistent withdrawal signs for many months.

Heroin use long-term effects

Repeated heroin use changes the physical structure and physiology of the brain, creating long-term imbalances in neuronal and hormonal systems that are not easily reversed 27, 28, 29. Studies have shown some deterioration of the brain’s white matter due to heroin use, which may affect decision-making abilities, the ability to regulate behavior, and responses to stressful situations 30, 31, 32.

Repeated heroin use often results in heroin use disorder also called heroin addiction, a chronic relapsing disease that goes beyond physical dependence and is characterized by uncontrollable drug-seeking, no matter the consequences 33. Heroin is extremely addictive no matter how it is administered, although routes of administration that allow it to reach the brain the fastest (i.e., injection and smoking) increase the risk of developing heroin addiction. Once a person has heroin addiction, seeking and using the drug becomes their primary purpose in life.

No matter how people ingest the drug, chronic heroin users experience a variety of medical complications, including insomnia and constipation. Lung complications including various types of pneumonia and tuberculosis may result from the poor health of the user as well as from heroin’s effect of depressing breathing. Many users experience mental disorders, such as depression and antisocial personality disorder. Men often experience sexual dysfunction and women’s menstrual cycles often become irregular. There are also specific consequences associated with different routes of administration. For example, people who repeatedly snort heroin can damage the mucosal tissues in their noses as well as perforate the nasal septum (the tissue that separates the nasal passages).

Medical consequences of chronic heroin injection use include scarred and/or collapsed veins, bacterial infections of the blood vessels and heart valves, abscesses (boils), and other soft-tissue infections. Many of the additives in street heroin may include substances that do not readily dissolve and result in clogging the blood vessels that lead to the lungs, liver, kidneys, or brain. This can cause infection or even death of small patches of cells in vital organs. Immune reactions to these or other contaminants can cause arthritis or other rheumatologic problems.

Heroin use increases the risk of being exposed to HIV, hepatitis B and C, other blood-borne viruses and other infectious agents through contact with infected blood or body fluids (e.g., semen, saliva) that results from the sharing of syringes and injection paraphernalia that have been used by infected individuals or through unprotected sexual contact with an infected person. Snorting or smoking does not eliminate the risk of infectious disease like hepatitis and HIV/AIDS because people under the influence of drugs still engage in risky sexual and other behaviors that can expose them to these diseases, which drug users can then pass on to their sexual partners and children.

Heroin and pregnancy

Using heroin during pregnancy can be dangerous, even deadly. Using heroin during pregnancy may cause serious problems, including:

- Birth defects. These are health conditions that are present at birth. Birth defects change the shape or function of one or more parts of the body. They can cause problems in overall health, how the body develops, or in how the body works.

- Placental abruption. This is a serious condition in which the placenta separates from the wall of the uterus before birth. The placenta supplies the baby with food and oxygen through the umbilical cord. Placental abruption can cause very heavy bleeding and can be deadly for both mother and baby.

- Preterm birth. This is birth that happens too early, before 37 weeks of pregnancy.

- Low birthweight. This is when a baby is born weighing less than 5 pounds, 8 ounces.

- Neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS). Neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) happens when a baby is exposed to a drug in the womb before birth causing the baby to become dependent, along with the mother and then goes through withdrawal after birth. Neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) symptoms include excessive crying, fever, irritability, seizures, slow weight gain, tremors, diarrhea, vomiting, and possibly death. NAS requires hospitalization and treatment with medication (often morphine) to relieve symptoms; the medication is gradually tapered off until the baby adjusts to being opioid-free. Methadone maintenance combined with prenatal care and a comprehensive drug treatment program can improve many of the outcomes associated with untreated heroin use for both the infant and mother, although infants exposed to methadone during pregnancy typically require treatment for NAS as well.

- Stillbirth. This is when a baby dies in the womb before birth, but after 20 weeks of pregnancy.

- Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). This is the unexplained death of a baby younger than 1 year old.

If you’re pregnant and using heroin, don’t stop taking it without getting treatment from your doctor first. Quitting suddenly sometimes called cold turkey can cause severe problems for your baby, including death. Your doctor or a drug-treatment center can treat you with drugs like methadone or buprenorphine. These drugs can help you gradually reduce your dependence on heroin in a way that’s safe for your baby.

Heroin dependence and addiction

As with some other drugs, a person can build up a tolerance to heroin. Tolerance means users need more and more heroin to have the same effect. After only a short time, the person using heroin will need to take larger doses to achieve the same effect. Soon their body will start to depend on heroin in order to function ‘normally’. For some people who are dependent on heroin, nothing else in life matters except the heroin. A person who is dependent on heroin may ignore his or her career, relationships and even basic needs like eating. Financial, legal and other personal problems may be related to heroin use. If someone who is dependent on heroin stops using it, they have withdrawal symptoms. These symptoms can include restlessness, muscle and bone pain, diarrhea, vomiting, and cold flashes with goose bumps. The person craves the heroin and this psychological dependence makes him or her panic if he or she cannot have it, even temporarily.

Repeated use of heroin often leads to heroin use disorder, sometimes called heroin addiction. Heroin addiction is more than physical dependence. Heroin addiction is a long-lasting brain disorder. When someone has it, they continue to use heroin even though it causes problems in their life. Some examples include health problems and not being able to meet responsibilities at work, school, or home. Getting and using heroin becomes their main purpose in life.

Treatment for heroin addiction

A variety of effective treatments are available for heroin addiction, including medicines to treat withdrawal symptoms, medicine to block the effects of opioids, and behavioral treatments. Often, a combination of medicine and behavioral treatment works best to restore a degree of normalcy to brain function and behavior, resulting in increased employment rates and lower risk of HIV and other diseases and criminal behavior. Although behavioral and medicine treatments can be extremely useful when utilized alone, research shows that for many people, integrating both types of treatments is the most effective approach.

Treatment options for heroin addiction include 34:

- Medications for opioid use disorder. The medicines used to treat opioid misuse and addiction are methadone (long-acting opioid), buprenorphine or naltrexone.

- Counseling and behavioral therapies.

- Medication-assisted therapy (MAT), which includes medication for opioid addiction, counseling, and behavioral therapies. This offers a “whole patient” approach to treatment, which can increase your chance of a successful recovery.

- Residential and hospital-based treatment.

- Residential programs combine housing and treatment services. You are living with your peers, and you can support each other to stay in recovery.

- Inpatient hospital-based programs combine health care and addiction treatment services for people with medical problems. Hospitals may also offer intensive outpatient treatment. All these types of treatments are very structured, and usually include several different kinds of counseling and behavioral therapies. They also often include medicines.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved opioid use disorder medications for the treatment of opioid use disorder include buprenorphine (often combined with naloxone), methadone, and naltrexone.

- Buprenorphine

- Partial mu-opioid receptor agonist.

- Suppresses and reduces cravings for opioids.

- Can be prescribed by any clinician with a current, standard Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) registration with Schedule 3 authority, in any clinical setting.

- The following buprenorphine products are FDA approved for the treatment of opioid use disorder:

- Generic Buprenorphine/naloxone sublingual tablets

- Buprenorphine sublingual tablets (Subutex)

- Buprenorphine/naloxone sublingual films (Suboxone)

- Buprenorphine/naloxone) sublingual tablets (Zubsolv)

- Buprenorphine/naloxone buccal film (Bunavail)

- Buprenorphine implants (Probuphine)

- Buprenorphine extended-release injection (Sublocade)

- Methadone

- Full mu-opioid receptor agonist.

- Reduces opioid cravings and withdrawal and blunts or blocks the effects of opioids.

- Can only be provided for opioid use disorder through a Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)-certified opioid treatment program (https://dpt2.samhsa.gov/treatment/directory.aspx)

- Naltrexone

- Opioid receptor antagonist.

- Blocks the euphoric and sedative effects of opioids and prevents feelings of euphoria.

- Should be started after a minimum of 7 to 10 days free of opioids to avoid precipitation of severe opioid withdrawal.

- Can be prescribed by any clinician with an active license to prescribe medications.

People getting treatment for heroin addiction should work with their doctor to come up with a treatment plan that fits their needs.

Buprenorphine

Buprenorphine is a partial opioid agonist at the mu-opioid receptor, meaning that it binds to those same opioid receptors but activates them less strongly than full opioid agonists do. Buprenorphine is the first medication to treat opioid use disorder that can be prescribed or dispensed in physician offices (with a current standard DEA registration with Schedule 3 authority), significantly increasing access to treatment 35. As with all medications used in opioid use disorder treatment, buprenorphine should be prescribed as part of a comprehensive treatment plan that includes counseling and other services to provide patients with a whole-person approach.

Buprenorphine is a partial opioid agonist. Like methadone, it can reduce cravings and withdrawal symptoms in a person with an opioid use disorder without producing euphoria, and patients tend to tolerate it well. Research has found buprenorphine to be similarly effective as methadone for treating opioid use disorders, as long as it is given at a sufficient dose and for sufficient duration 36. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved buprenorphine in 2002, making it the first medication eligible to be prescribed by certified physicians through the Drug Addiction Treatment Act 37. This approval eliminates the need to visit specialized treatment clinics, thereby expanding access to treatment for many who need it. Additionally, the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act (CARA), which was signed into law in July 2016, temporarily expands eligibility to prescribe buprenorphine-based drugs for medication-assisted treatment (MAT) to qualifying nurse practitioners and physician assistants through October 1, 2021 37. Buprenorphine has been available for opioid use disorders since 2002 as a tablet and since 2010 as a sublingual film 38. The FDA approved a 6-month subdermal buprenorphine implant in May 2016 and a once-monthly buprenorphine injection in November 2017 37. These formulations are available to patients stabilized on buprenorphine and will eliminate the treatment barrier of daily dosing for these patients.

When taken as prescribed, buprenorphine is safe and effective.

Buprenorphine has unique pharmacological properties that help:

- Diminish the effects of physical dependency to opioids, such as withdrawal symptoms and cravings

- Increase safety in cases of overdose

- Lower the potential for misuse

The following buprenorphine products are FDA approved for the treatment of opioid use disorder:

- Generic Buprenorphine/naloxone sublingual tablets

- Buprenorphine sublingual tablets (Subutex)

- Buprenorphine/naloxone sublingual films (Suboxone)

- Buprenorphine/naloxone) sublingual tablets (Zubsolv)

- Buprenorphine/naloxone buccal film (Bunavail)

- Buprenorphine implants (Probuphine)

- Buprenorphine extended-release injection (Sublocade)

To begin treatment with buprenorphine, an opioid use disorder patient must abstain from using opioids for at least 12 to 24 hours and be in the early stages of opioid withdrawal. Patents with opioids in their bloodstream or who are not in the early stages of withdrawal, may experience acute withdrawal. Long acting opioids, such as methadone, require at least 48-72 hours since last use before initiating buprenorphine. Short acting opioids (for example, heroin) require approximately 12 hours since last use for sufficient withdrawal to occur in order to safely initiate buprenorphine treatment. Some opioid such as fentanyl may require greater than 12 hours. Clinical presentation should guide this decision as individual presentations will vary.

After a patient has discontinued or greatly reduced their opioid use, no longer has cravings, and is experiencing few, if any, side effects, if needed, the dose of buprenorphine may be adjusted. Due to the long-acting agent of buprenorphine, once patients are stabilized, it may be possible to switch from every day to alternate-day dosing.

The dose of buprenorphine depends on the severity of withdrawal symptoms, and the history of last opioid use (see Figure 2 flowchart for dosing advice).

The length of time a patient receives buprenorphine is tailored to meet the needs of each patient, and in some cases, treatment can be indefinite. To prevent possible relapse, individuals can engage in on-going treatment—with or without medication for opioid use disorder.

Common side effects of buprenorphine include 39:

- Constipation, headache, nausea, and vomiting

- Dizziness

- Drowsiness and fatigue

- Sweating

- Dry mouth

- Tooth decay

- Muscle aches and cramps

- Inability to sleep

- Fever

- Blurred vision or dilated pupils

- Tremors

- Palpitations

- Disturbance in attention

Serious side effects of buprenorphine include 39:

- Respiratory distress

- Overdose

- Adrenal insufficiency

- Dependence

- Withdrawal

- Itching, pain, swelling, and nerve damage (implant)

- Pain at injection site (injection)

- Neonatal abstinence syndrome (in newborns)

Figure 4. Buprenorphine quick start guide

[Source 35 ]Methadone

Methadone is a medication used to treat opioid use disorder as well as for pain management 40. Methadone is a long-acting full opioid agonist that eliminates withdrawal symptoms and relieves drug cravings by acting on opioid receptors in the brain—the same receptors that other opioids such as heroin, morphine, and opioid pain medications activate. Although it occupies and activates these opioid receptors, it does so more slowly than other opioids and, in an opioid-dependent person, treatment doses do not produce euphoria. Methadone has been used successfully for more than 40 years to treat opioid use disorder and must be dispensed through a Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) certified opioid treatment programs 41. Taken daily, it is available in liquid, powder and diskettes forms.

Methadone is one component of a comprehensive treatment plan, which includes counseling and other behavioral health therapies to provide patients with a whole-person approach. Methadone helps individuals achieve and sustain recovery and to reclaim active and meaningful lives.

Patients taking methadone to treat opioid use disorder must receive the medication under the supervision of a practitioner. After a period of stability (based on progress and proven, consistent compliance with the medication dosage), patients may be allowed to take methadone at home between program visits 40.

The length of time a person receives methadone treatment varies 40. According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse publication Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment: A Research-Based Guide (Third Edition), the length of methadone treatment should be a minimum of 12 months 42. Some patients may require long-term maintenance. Patients must work with their practitioner to gradually reduce their methadone dosage to prevent withdrawal.

When taken as prescribed, methadone is safe and effective.

Methadone medication is specifically tailored for the individual patient (and doses are often adjusted and readjusted) and is never to be shared with or given to others. This is particularly important for patients who take methadone at home and are not required to take medication under direct supervision at a Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) certified opioid treatment program.

Other medications may interact with methadone and cause heart conditions. Even after the effects of methadone wear off, the medication’s active ingredients remain in the body for much longer. Unintentional overdose is possible if patients do not take methadone as prescribed.

The following tips can help you achieve the best treatment results:

- Never use more than the amount prescribed, and always take at the times prescribed. If a dose is missed, or if it feels like it’s not working, do not take an extra dose of methadone

- Do not consume alcohol while taking methadone.

- Be careful driving or operating machinery on methadone.

- Call your local emergency services number if too much methadone is taken or if an overdose is suspected.

- Prevent children and pets from accidental ingestion by storing it out of reach.

- Store methadone at room temperature and away from light.

- Do not shared your methadone with anyone even if they have similar symptoms or suffer from the same condition.

- Dispose of unused methadone safely.

Common side effects of methadone include:

- Restlessness

- Nausea or vomiting

- Slow breathing

- Itchy skin

- Heavy sweating

- Constipation

- Sexual problems

Serious side effects of methadone include:

- Experience difficulty breathing or shallow breathing

- Feel lightheaded or faint

- Experience hives or a rash; swelling of the face, lips, tongue, or throat

- Feel chest pain

- Experience a fast or pounding heartbeat

- Experience hallucinations or confusion.

Naltrexone

Naltrexone is a medication approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat both alcohol use disorder and opioid use disorder 43. Naltrexone is an opioid antagonist, which means that it works by blocking the activation of opioid receptors 37. Naltrexone works differently than methadone and buprenorphine. Instead of controlling withdrawal symptoms and cravings, naltrexone treats opioid use disorder by preventing any opioid drug from producing rewarding effects such as euphoria. Naltrexone blocks the euphoric and sedative effects of opioids such as heroin, morphine, and codeine. Because of this, you would take naltrexone to prevent a relapse, not to try to get off opioids. You have to be off opioids for at least 7 days after you last use of short-acting opioids and 10 to 14 days for long-acting opioids, before starting naltrexone. Otherwise you could have bad withdrawal symptoms.

Naltrexone is not an opioid, is not addictive, and does not cause withdrawal symptoms with stop of use. There is no abuse and diversion potential with naltrexone.

Naltrexone use for ongoing opioid use disorder treatment has been somewhat limited because of poor adherence and tolerability by patients. However, in 2010, an injectable, long-acting form of naltrexone (Vivitrol), originally approved for treating alcohol use disorder, was FDA-approved for treating opioid use disorder 37. Because the long-acting form of naltrexone effects last for weeks, Vivitrol is a good option for patients who do not have ready access to health care or who struggle with taking their medications regularly.

While the oral naltrexone formulation will also block opioid receptors, only the long acting injectable naltrexone formulation (Vivitrol) is FDA approved as a medication for opioid use disorder and requires Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) 43.

Patients on naltrexone, who discontinue use or relapse after a period of abstinence, may have a reduced tolerance to opioids. Therefore, taking the same, or even lower doses of opioids used in the past can cause life-threatening consequences 43.

You should not take naltrexone if you:

- Currently use or have a physical dependence on opioid-containing medicines or opioid drugs, such as heroin, or currently experiencing opioid withdrawal symptoms

- Experience opioid withdrawal symptoms. Withdrawal symptoms may happen when a patient was taking opioid-containing medicines or opioid drugs regularly and then stopped.

- Symptoms of opioid withdrawal may include: anxiety, sleeplessness, yawning, fever, sweating, teary eyes, runny nose, goose bumps, shakiness, hot or cold flushes, muscle aches, muscle twitches, restlessness, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, or stomach cramps.

Common side effects of naltrexone may include:

- nausea

- sleepiness

- headache

- dizziness

- vomiting

- decreased appetite

- painful joints

- muscle cramps

- cold symptoms

- trouble sleeping

- toothache

Serious side effects of naltrexone may include:

- Severe reactions at the site of injection:

- intense pain

- tissue death, surgery may be required

- swelling, lumps, or area feels hard

- scabs, blisters, or open wounds

- Liver damage or hepatitis is possible:

- stomach area pain lasting more than a few days

- dark urine

- yellowing of the whites of your eyes

- tiredness

- Serious allergic reactions

- skin rash

- swelling of face, eyes, mouth, or tongue

- trouble breathing or wheezing

- chest pain

- feeling dizzy or faint

- Pneumonia

- Depressed mood

- Risk of Opioid Overdose. Patients should tell family and the people they are closest to about the increased sensitivity to opioids and the risk of overdose. Accidental overdose can happen in two ways:

- Naltrexone blocks the effects of opioids, such as heroin or opioid pain medicines. Patients who try to overcome this blocking effect by taking large amounts of opioids may experience serious injury, coma, or death.

- After receiving a dose of naltrexone, the blocking effect slowly decreases and completely goes away over time. Patients who are taking naltrexone for an opioid use disorder can become more sensitive to the effects of opioids at the dose used before, or even lower amounts. Using opioids while on naltrexone can lead to overdose and death.

Behavior therapy

As part of a drug treatment program, behavior therapy — a form of psychotherapy or counseling — can be done by a psychologist or psychiatrist, or you may receive counseling from a licensed alcohol and drug counselor. Therapy and counseling may be done with an individual, a family or a group. The therapist or counselor can:

- Help you develop ways to cope with your drug cravings

- Suggest strategies to avoid drugs and prevent relapse

- Change your attitudes and behaviors related to drug use

- Offer suggestions on how to deal with a relapse if it occurs

- Talk about issues regarding your job, legal problems, and relationships with family and friends

- Include family members to help them develop better communication skills and be supportive

- Address other mental health conditions

- Build healthy life skills

There are different types of counseling to treat opioid use disorder, including:

- Individual counseling, which may include setting goals, talking about setbacks, and celebrating progress. You may also talk about legal concerns and family problems. Counseling often includes specific behavioral therapies, such as:

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) helps you recognize and stop negative patterns of thinking and behavior. It teaches you coping skills, including how to manage stress and change the thoughts that cause you to want to misuse opioids.

- Motivational enhancement therapy helps you build up motivation to stick with your treatment plan

- Contingency management focuses on giving you incentives for positive behaviors such as staying off the opioids

- Group counseling, which can help you feel that you are not alone with your issues. You get a chance to hear about the difficulties and successes of others who have the same challenges. This can help you to learn new strategies for dealing with the situations you may come across.

- Family counseling includes partners or spouses and other family members who are close to you. It can help to repair and improve your family relationships.

Counselors can also refer you to other resources that you might need, such as:

- Peer support groups, including 12-step programs like Narcotics Anonymous (https://na.org) or SMART Recovery (https://www.smartrecovery.org)

- Spiritual and faith-based groups

- HIV testing and hepatitis screening

- Case or care management

- Employment or educational supports

- Organizations that help you find housing or transportation

Self-help groups

Self-help support groups, such as Narcotics Anonymous (https://na.org) or SMART Recovery (https://www.smartrecovery.org), help people who are addicted to drugs. The self-help support group message is that addiction is an ongoing disorder with a danger of relapse. Self-help support groups can decrease the sense of shame and isolation that can lead to relapse.

You can also find help and treatment resources by visiting the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website (https://www.samhsa.gov) or by calling the helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

Your therapist or licensed counselor can help you locate a self-help support group. You may also find support groups in your community or on the internet.

Ongoing treatment

Even after you’ve completed initial treatment, ongoing treatment and support can help prevent a relapse. Follow-up care can include periodic appointments with your counselor, continuing in a self-help program or attending a regular group session. Seek help right away if you relapse.

Relapse prevention

Once you’ve been addicted to a drug, you’re at high risk of falling back into a pattern of addiction. If you do start using the drug, it’s likely you’ll lose control over its use again — even if you’ve had treatment and you haven’t used the drug for some time.

- Follow your treatment plan. Monitor your cravings. It may seem like you’ve recovered and you don’t need to keep taking steps to stay drug-free. But your chances of staying drug-free will be much higher if you continue seeing your therapist or counselor, going to support group meetings and taking prescribed medicine.

- Avoid high-risk situations. Don’t go back to the neighborhood where you used to get your drugs. And stay away from your old drug crowd.

- Get help immediately if you use the drug again. If you start using the drug again, talk to your doctor, your mental health provider or someone else who can help you right away.

Studies show that people with opioid use disorder who follow detoxification with complete abstinence are very likely to relapse, or return to using the drug 44. While relapse is a normal step on the path to recovery, it can also be life threatening, raising the risk for a fatal overdose 45. Therefore, an important way to support recovery from heroin or prescription opioid use disorder is to maintain abstinence from those drugs. Someone in recovery can also use medications that reduce the negative effects of withdrawal and cravings without producing the euphoria that the original drug of abuse caused. For example, the FDA recently approved lofexidine, a non-opioid medicine designed to reduce opioid withdrawal symptoms 37. Methadone and buprenorphine are other medications approved for this purpose.

Heroin withdrawal

Heroin withdrawal symptoms can start after a matter of hours without a dose of heroin. Symptoms of heroin withdrawal may include:

- Alertness

- Cravings

- Diarrhea and vomiting

- Stomach cramps

- Goose bumps

- Sweating

- Bone, joint and muscle pain and twitching

- Dilated pupils

- Mood swings and crying

- Insomnia

- Yawning

Heroin withdrawal symptoms are not life-threatening, like alcohol or benzodiazepine withdrawal 8. Some or all of these symptoms may be seen; the patient does not need all to be diagnosed with heroin withdrawal 8.

Heroin withdrawal treatment

When people addicted to opioids like heroin first quit, they undergo withdrawal symptoms (pain, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting), which may be severe. Medications can be helpful in this detoxification stage to ease craving and other physical symptoms that can often prompt a person to relapse. The FDA approved lofexidine, a non-opioid medicine designed to reduce opioid withdrawal symptoms. While not a treatment for addiction itself, detoxification is a useful first step when it is followed by some form of evidence-based treatment.

Medications developed to treat opioid use disorders work through the same opioid receptors as the addictive drug, but are safer and less likely to produce the harmful behaviors that characterize a substance use disorder. 3 types of medications include: (1) agonists, which activate opioid receptors; (2) partial agonists, which also activate opioid receptors but produce a smaller response; and (3) antagonists, which block the receptor and interfere with the rewarding effects of opioids. A particular medication is used based on a patient’s specific medical needs and other factors.

Medications developed to treat opioid use disorders include:

- Methadone (Dolophine® or Methadose®) is a slow-acting opioid agonist. Methadone is taken orally so that it reaches the brain slowly, dampening the “high” that occurs with other routes of administration while preventing withdrawal symptoms. Methadone has been used since the 1960s to treat heroin use disorder and is still an excellent treatment option, particularly for patients who do not respond well to other medications. Methadone is only available through approved outpatient treatment programs, where it is dispensed to patients on a daily basis.

- Buprenorphine (Subutex®) is a partial opioid agonist. Buprenorphine relieves drug cravings without producing the “high” or dangerous side effects of other opioids. Suboxone is a novel formulation of buprenorphine that is taken orally or sublingually and contains naloxone (an opioid antagonist) to prevent attempts to get high by injecting the medication. If a person with a heroin use disorder were to inject Suboxone, the naloxone would induce withdrawal symptoms, which are averted when taken orally as prescribed. FDA approved buprenorphine in 2002, making it the first medication eligible to be prescribed by certified physicians through the Drug Addiction Treatment Act. This approval eliminates the need to visit specialized treatment clinics, thereby expanding access to treatment for many who need it. Additionally, the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act (CARA), which was signed into law in July 2016, temporarily expands prescribing eligibility to prescribe buprenorphine-based drugs for medication-assisted treatment to qualifying nurse practitioners and physician assistant through October 1, 2021. In February 2013, FDA approved two generic forms of Suboxone, making this treatment option more affordable. The FDA approved a 6-month subdermal buprenorphine implant in May 2016 and a once-monthly buprenorphine injection in November 2017, which eliminates the treatment barrier of daily dosing.

- Naltrexone (Vivitrol®) is an opioid antagonist. Naltrexone blocks the action of opioids, is not addictive or sedating, and does not result in physical dependence; however, patients often have trouble complying with the treatment, and this has limited its effectiveness. In 2010, the injectable long-acting formulation of naltrexone (Vivitrol) received FDA approval for a new indication for the prevention of relapse to opioid dependence following opioid detoxification. Administered once a month, Vivitrol may improve compliance by eliminating the need for daily dosing.

Heroin overdose

It’s possible to overdose on heroin. This happens when a person uses so much heroin that it causes a life-threatening reaction or death. All heroin users are at risk of an overdose because they never know the actual strength of the drug they are taking or what may have been added to it. And people often use heroin along with other drugs or alcohol. This can increase the risk of an overdose.

When people overdose on heroin, their heart rate and breathing slow down to such an extent that a user cannot survive without medical help. Their breathing may slow do so much that not enough oxygen reaches the brain. This condition is called hypoxia. Hypoxia can lead to a coma, permanent brain damage, or death.

The symptoms of heroin overdose include:

- Dangerously low body temperature

- Slowed breathing

- Blue lips, gums or fingertips

- Limp body

- Pale, cold, clammy face and skin

- Vomiting or gurgling sounds

- Inability to speak or be awakened

- Slow and shallow breathing

- Slow or irregular heartbeat or pulse

- Small pupils

- Vomiting

- Unresponsiveness (doesn’t wake up when shaken or called)

- Unconsciousness

- Convulsions and coma.

If someone who has taken heroin or other drugs does not respond when you talk to them, is snoring loudly or making gurgling noises, they may be in a coma and having trouble breathing. Do not assume that they are just ‘sleeping off’ the effects. Their airway may be blocked by their tongue falling back or other blockages. This is a medical emergency. If you can’t wake them, dial your local emergency services number to call an ambulance immediately. Ambulance officers, family and friends can give the medication naloxone (Narcan) to reverse the effects of heroin overdose. Naloxone (Narcan) is a drug that can temporarily reverse heroin overdose. It works by blocking opioid drugs from attaching to opioid receptors in the brain.

Basic Life Support and Advanced Cardiac Life Support principles should be followed during the resuscitation of a heroin overdose 46. Adequate intravenous (IV) access is necessary so enough fluids and medication can be administered. An initial intravenous dose of 0.4 to 0.8 mg of naloxone will usually quickly reverse neurologic and cardiorespiratory symptoms if the overdose is pure heroin and not contaminated by carfentanyl and similar substances 47. Frequent monitoring of vital signs and cardiorespiratory status is needed to make sure heroin is cleared from the patient system. Patients treated with naloxone after heroin overdose may be safely released without transport to the hospital or emergency room if they have normal mentation and vital signs 8. In the absence of co-intoxicants and further opioid use, there is a very low risk of death from rebound heroin toxicity 48.

Naloxone

Naloxone is a US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved medicine used to quickly reverse an opioid or narcotic overdose 49. Naloxone is available as a nasal spray (Narcan 4mg, Kloxxado 8mg) or an injection (Zimhi 5 mg/0.5 mL). Naloxone is a opioid antagonist that works by attaching to opioid receptors and therefore reverses and blocks the effects of other opioids. Naloxone can quickly restore normal breathing to a person if their breathing has slowed or stopped because of an opioid overdose. But, naloxone has no effect on someone who does not have opioids in their system, and it is not a treatment for opioid use disorder. Examples of opioids sometimes called narcotics are buprenorphine, heroin, fentanyl, oxycodone (OxyContin), hydrocodone (Vicodin, Lortab), codeine, morphine, hydromorphone, meperidine, methadone, oxymorphone, and tramadol. There are no age restrictions on the use of naloxone; it can be used for suspected overdose in infants and children through elderly people. Naloxone saves lives. From 1996 to 2014, at least 26,500 opioid overdoses in the United States were reversed by laypersons using naloxone. Naloxone does not cause physical or psychological dependence and has virtually no effect in a healthy non-dependent person 50.

Naloxone should be used as soon as possible to treat a known or suspected opioid overdose emergency, if there are signs of slowed breathing, severe sleepiness or the person is not able to respond (loss of consciousness) 13. Once naloxone has been given the patient must receive emergency medical care straight away, even if they wake up.

First, recognize signs of an opioid overdose:

- Limp body

- Pale, clammy face

- Blue lips, gums or fingertips

- Vomiting or gurgling sounds

- Inability to speak or be awakened

- Slow and shallow breathing

- Slow or irregular heartbeat or pulse

- Small pupils

- Vomiting

- Unresponsiveness (doesn’t wake up when shaken or called)

- Unconsciousness

If you see these symptoms, call your local emergency services number immediately and consider the use of naloxone if available. If the person has stopped breathing or if breathing is very weak, begin CPR (best performed by someone who has training).

Naloxone is a prescription medicine but in many states, naloxone is available from a pharmacist without a prescription from your doctor, under state Naloxone Access Laws or alternate arrangements. Furthermore, naloxone is not a controlled substance, according to the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).

Naloxone works to reverse opioid overdose in the body for only 30 to 90 minutes. But many opioids remain in the body longer than that. Because of this, it is possible for a person to still experience the effects of an overdose after a dose of naloxone wears off. Also, some opioids are stronger and might require multiple doses of naloxone. Therefore, one of the most important steps to take is to call your local emergency services number for an ambulance so the individual can receive immediate medical attention.

People who are given naloxone should be observed constantly until emergency care arrives. They should be monitored for another 2 hours after the last dose of naloxone is given to make sure breathing does not slow or stop.

People with physical dependence on opioids may have opioid withdrawal symptoms within minutes after they are given naloxone.

Opioid withdrawal symptoms might include:

- headaches,

- changes in blood pressure,

- rapid heart rate,

- sweating,

- nausea,

- vomiting,

- feeling nervous, restless, or irritable

- tremors.

- body aches

- dizziness or weakness

- diarrhea, stomach pain, or nausea

- fever, chills, or goose bumps

- sneezing or runny nose in the absence of a cold

While this is uncomfortable, it is usually not life threatening. The risk of death for someone overdosing on opioids is worse than the risk of having a bad reaction to naloxone.

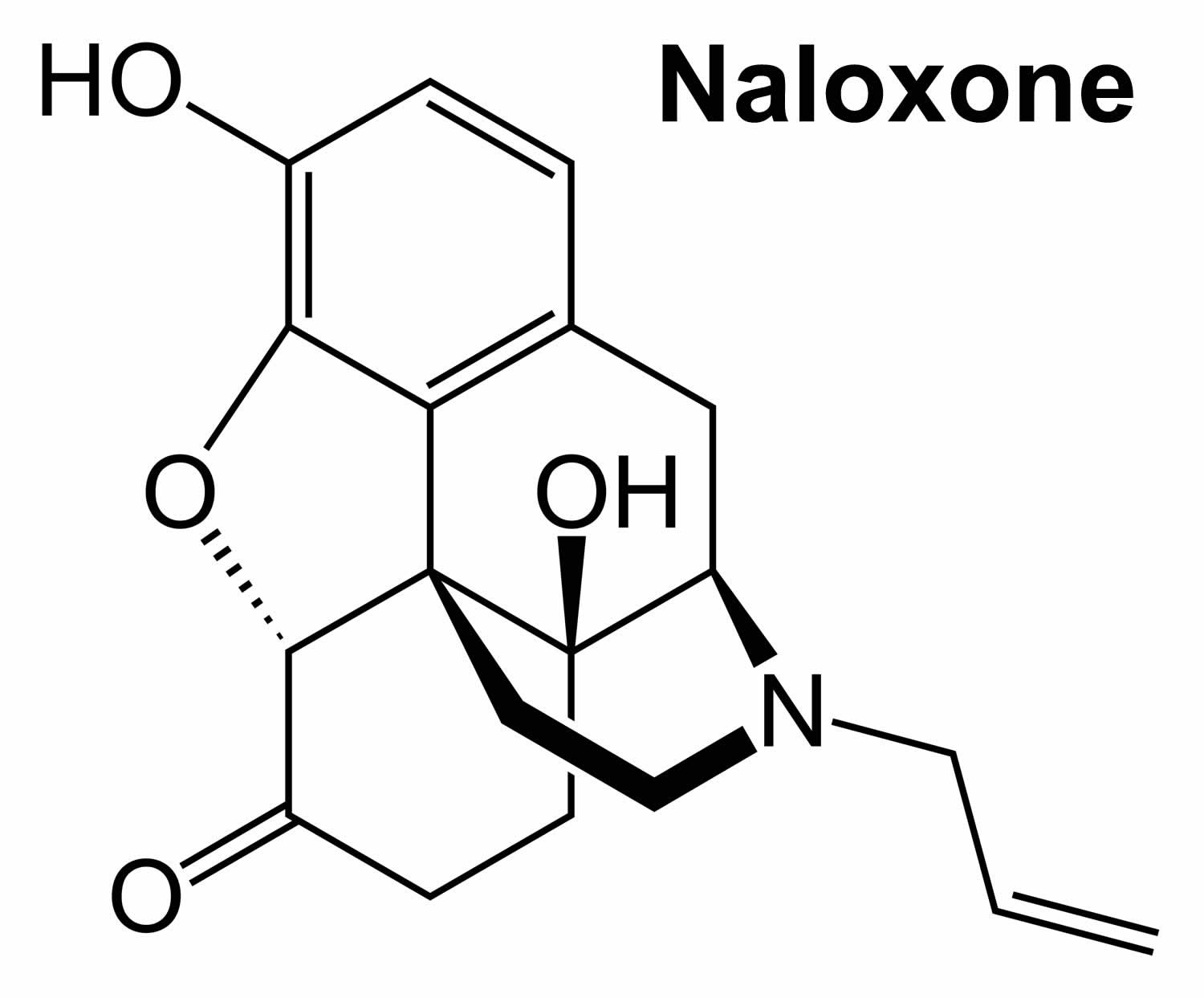

Figure 5. Naloxone chemical structure

How to use and give naloxone

Home preparations include a naloxone nasal spray (Narcan 4mg, Kloxxado 8mg) given to someone while they lie on their back or a device that automatically injects naloxone (Zimhi 5 mg/0.5 mL) into the thigh. Sometimes more than one dose is needed. You may need another naloxone injection every 2 to 3 minutes until emergency help arrives.

The person’s breathing also needs to be monitored. If the person stops breathing, consider rescue breaths and CPR if you are trained until first responders arrive.

Naloxone works to reverse opioid overdose in the body for only 30 to 90 minutes. But many opioids remain in the body longer than that. Because of this, it is possible for a person to still experience the effects of an overdose after a dose of naloxone wears off. Also, some opioids are stronger and might require multiple doses of naloxone. Therefore, one of the most important steps to take is to call your local emergency services number for an ambulance so the individual can receive immediate medical attention.

People who are given naloxone should be observed constantly until emergency care arrives. They should be monitored for another 2 hours after the last dose of naloxone is given to make sure breathing does not slow or stop.

People with physical dependence on opioids may have withdrawal symptoms within minutes after they are given naloxone. Withdrawal symptoms might include headaches, changes in blood pressure, rapid heart rate, sweating, nausea, vomiting, and tremors. While this is uncomfortable, it is usually not life threatening. The risk of death for someone overdosing on opioids is worse than the risk of having a bad reaction to naloxone.

Naloxone injection instructions

- Each naloxone injection contains only one dose of medicine and cannot be reused.

- Place the patient on their back and when you are ready to inject, pull off cap to expose needle.

- Do not put your finger on top of the device. For a child under the age of 1 years old, pinch the thigh muscle while administering the dose.

- Hold naloxone injection by finger grips only and slowly insert the needle into the thigh.

- After needle is in thigh you should push the plunger all the way down until it clicks and then hold for 2 seconds.

- Right after the injection, using one hand with fingers behind the needle, slide the safety guard over the needle. You should not use two hands to activate the safety guard. Put the used syringe into the blue case and close the case.

Naloxone nasal spray instructions

To give naloxone nasal spray, follow these steps:

- Lay the person on their back to give the medication. Support their neck with your hand and allow the head to tilt back before giving the nasal spray.

- Remove the naloxone nasal spray from the box. Peel back the tab to open the spray.

- Do not prime the nasal spray before using it.

- Hold the naloxone nasal spray with your thumb on the bottom of the plunger and your first and middle fingers on either side of the nozzle.

- Gently insert the tip of the nozzle into one nostril, until your fingers on either side of the nozzle are against the bottom of the person’s nose. Provide support to the back of the person’s neck with your hand to allow the head to tilt back.

- Press the plunger firmly to release the medication.

- Remove the nasal spray nozzle from the nostril after giving the medication.

- Turn the person on their side (recovery position) and call for emergency medical assistance immediately after giving the first naloxone dose.

- If the person does not respond by waking up, to voice or touch, or breathing normally or responds and then relapses, give another dose. If needed, give additional doses (repeating steps 2 through 7) every 2 to 3 minutes in alternate nostrils with a new nasal spray each time until emergency medical assistance arrives.

- Put the used nasal spray(s) back in the container and out of reach of children until you can safely dispose of it.

Ask your pharmacist or doctor for a copy of the manufacturer’s information for the patient.

After giving a dose of naloxone

- You need to get emergency medical help as soon as you have given the injection or nasal spray.

- Tell the healthcare provider that you have given a dose of naloxone.

- Turn the patient on their side to place them in the recovery position after giving them the naloxone.

- If symptoms continue or return after using the naloxone, an additional dose may be needed.

- If you are giving additional doses, use a new naloxone nasal spray or new naloxone injection every 2 to 3 minutes and continue to closely watch the person until emergency help has arrived.

- You may need to perform CPR (cardiopulmonary resuscitation) on the person while you are waiting for emergency help to arrive.

- Using naloxone does not take the place of emergency medical care.

Figure 6. Recovery position

How is naloxone given?

Naloxone should be given to any person who shows signs of an opioid overdose or when an opioid overdose is suspected. Naloxone can be given as a nasal spray (Narcan 4mg, Kloxxado 8mg) or it can be injected (Zimhi 5 mg/0.5 mL) into the muscle, under the skin, or into the veins. Sometimes more than one dose is needed. You may need another naloxone injection every 2 to 3 minutes until emergency help arrives.

The person’s breathing also needs to be monitored. If the person stops breathing, consider rescue breaths and CPR if you are trained until first responders arrive.

Naloxone works to reverse opioid overdose in the body for only 30 to 90 minutes. But many opioids remain in the body longer than that. Because of this, it is possible for a person to still experience the effects of an overdose after a dose of naloxone wears off. Also, some opioids are stronger and might require multiple doses of naloxone. Therefore, one of the most important steps to take is to call your local emergency services number for an ambulance so the individual can receive immediate medical attention.

People who are given naloxone should be observed constantly until emergency care arrives. They should be monitored for another 2 hours after the last dose of naloxone is given to make sure breathing does not slow or stop.

People with physical dependence on opioids may have withdrawal symptoms within minutes after they are given naloxone. Withdrawal symptoms might include headaches, changes in blood pressure, rapid heart rate, sweating, nausea, vomiting, and tremors. While this is uncomfortable, it is usually not life threatening. The risk of death for someone overdosing on opioids is worse than the risk of having a bad reaction to naloxone.

What if I’m not sure if someone has an opioid overdose?

Giving someone naloxone, who is suspected to have an opioid overdose, in an emergency won’t hurt them, but it could save their life! Naloxone will not harm someone who does not have opioids in their system. Naloxone is a opioid antagonist that works in the brain only at the opioid receptor, binding to the receptors and blocking the opioids and the effects of opioids. If someone is having a different medical emergency – such as a diabetic coma or cardiac arrest – and you give them naloxone, the drug won’t have any effect or harm them.

Naloxone is being used more by police officers, emergency medical technicians, and non-emergency first responders than before. In most states, people who are at risk or who know someone at risk for an opioid overdose can be trained on how to give naloxone. Families can ask their pharmacists or health care provider how to use the naloxone devices.

Is naloxone safe?

Yes. There is no evidence of significant adverse reactions to naloxone 51. Administering naloxone in cases of opioid overdose can cause withdrawal symptoms when the person is dependent on opioids; this is uncomfortable without being life threatening 52, 53. The risk that someone overdosing on opioids will have a serious adverse reaction to naloxone is far less than their risk of dying from overdose 54, 55, 56, 57. Naloxone works if a person has opioids in their system and has no harmful effect if opioids are absent. Naloxone should be given to any person who shows signs of an opioid overdose or when an opioid overdose is suspected 58.

What are the different types of naloxone?

Naloxone comes in two FDA-approved forms: injectable naloxone (Zimhi 5 mg/0.5 mL) and prepackaged nasal spray naloxone (Narcan 4mg, Kloxxado 8mg). No matter what dosage form you use, it’s important to receive training on how and when to use naloxone. You should also read the product instructions and check the expiration date.

- Injectable brands of naloxone (Zimhi 5 mg/0.5 mL). Typically, the proper dose must be drawn up from a vial. Usually, it is injected with a needle into muscle, although it also may be administered into a vein or under the skin. The FDA recently approved Zimhi, a single-dose, prefilled syringe that can be injected into the muscle or under the skin.

- Note: Some people use an improvised nasal spray emergency kit not approved by the FDA that combines injectable naloxone with an attachment designed to deliver naloxone through the nose. However, this improvised intranasal device is not easy to assemble, especially when under pressure in an emergency, and requires training beforehand. Additionally, the FDA-approved naloxone devices have been shown to produce substantially higher blood levels of naloxone than the improvised nasal spray. These outcomes suggest that the approved prepackaged nasal spray technology is preferable over non-FDA-approved forms.

- Prepackaged Nasal Spray (generic naloxone, Narcan 4mg, Kloxxado 8mg), is an FDA-approved prefilled, needle-free device that requires no assembly and is sprayed into one nostril while the person lays on their back. This device can also be easier for loved ones and bystanders without formal training to use. (In Europe, Nalscue 1 mg, Nyxoid 2 mg, Ventizolve 1.4 mg).

Is there a preferable naloxone delivery system?

All FDA-approved forms: injectable naloxone (Zimhi 5 mg/0.5 mL) and prepackaged nasal spray naloxone (Narcan 4mg, Kloxxado 8mg) used by first responders deliver the stated dose of naloxone and can be highly effective in reversing an opioid overdose. Study findings released in March 2019 59 suggests that the FDA-approved naloxone devices deliver higher blood levels of naloxone than the improvised nasal devices.

Where can I get naloxone?

Many pharmacies carry naloxone. In some states, you can get naloxone from a pharmacist even if your doctor did not write you a prescription for it. It is also possible to get naloxone from community-based distribution programs, local public health groups, or local health departments, free of charge.

To find naloxone in your area, go to the Naloxone Finder (https://www.getnaloxonenow.org/#getnaloxone)

How much does naloxone cost?

The cost varies depending on where you get the naloxone, how you get it, and what type you get. Patients with insurance should check with their insurance company to see if this medicine is covered. Patients without insurance can check the retail costs at their local pharmacies. Some drug companies have cost assistance programs for patients unable to pay for it.

How does naloxone work?

Naloxone is an opioid antagonist, which means that it binds to opioid receptors and reverses or blocks the effects of other opioids. Naloxone is so strongly attracted to the receptors that it knocks other opioids off. When opioids are sitting on their receptors, they change the activity of the cell.

Opioid receptors are found on nerve cells all around the body:

- In the brain, opioids produce feelings of comfort and sleepiness.

- In the brainstem, opioids relax breathing and reduce cough.

- In the spinal cord and peripheral nerves, opioids slow down pain signals.

- In the gastrointestinal tract, opioids are constipating.

These opioid actions can be helpful. The body actually produces its own opioids called “endorphins,” which help calm the body in times of stress. Endorphins help produce the “runner’s high” that helps marathon runners get through grueling races. But opioid drugs, like prescription pain medications or heroin, have much stronger opioid effects. And they are more dangerous.

Over time, frequent opioid use makes the body dependent on the drugs. When the opioids are taken away, the body reacts with withdrawal symptoms such as headache, racing heart, soaking sweats, vomiting, diarrhea, and tremors. For many, the symptoms feel unbearable.

Over time, opioid receptors also become less responsive and the body develops tolerance to the drugs. More drugs are needed to produce the same effects, which makes overdose more likely.

Opioid overdose is dangerous especially for its effect in the brainstem, relaxing breathing. Breathing can be relaxed so much that it stops, leading to death.

Naloxone knocks opioids off their receptors all around the body. In the brainstem, naloxone can restore the drive to breathe. And save a life.

But even if naloxone is successful, opioids are still floating around, so expert medical care should be sought as soon as possible. Naloxone works for 30-90 minutes before the opioids return to their receptors.

Naloxone may promote withdrawal because it knocks opioids off their receptors so quickly. But otherwise naloxone is safe and unlikely to produce side effects.

- Milella MS, D’Ottavio G, De Pirro S, Barra M, Caprioli D, Badiani A. Heroin and its metabolites: relevance to heroin use disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2023 Apr 8;13(1):120. doi: 10.1038/s41398-023-02406-5[↩][↩]

- Jones JD, Campbell A, Metz VE, Comer SD. No evidence of compensatory drug use risk behavior among heroin users after receiving take-home naloxone. Addict Behav. 2017 Aug;71:104-106. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.03.008[↩]

- Fiorentin TR, Krotulski AJ, Martin DM, Browne T, Triplett J, Conti T, Logan BK. Detection of Cutting Agents in Drug-Positive Seized Exhibits within the United States. J Forensic Sci. 2019 May;64(3):888-896. doi: 10.1111/1556-4029.13968[↩]

- Lucas P, Baron EP, Jikomes N. Medical cannabis patterns of use and substitution for opioids & other pharmaceutical drugs, alcohol, tobacco, and illicit substances; results from a cross-sectional survey of authorized patients. Harm Reduct J. 2019 Jan 28;16(1):9. doi: 10.1186/s12954-019-0278-6[↩]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Epidemiologic Trends in Drug Abuse, in Proceedings of the Community Epidemiology Work Group, January 2012. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse, 66.[↩][↩]

- NIDA. 2023, December 14. What is the scope of heroin use in the United States?. Retrieved from https://nida.nih.gov/publications/research-reports/heroin/scope-heroin-use-in-united-states[↩]

- Miech, R. A., Johnston, L. D., Patrick, M. E., & O’Malley, P. M. (2024). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2023: Overview and detailed results for secondary school students. Monitoring the Future Monograph Series. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan. https://monitoringthefuture.org/results/annual-reports/[↩]

- Oelhaf RC, Azadfard M. Heroin Toxicity. [Updated 2023 May 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430736[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Pavarin RM, Fioritti A, Sanchini S. Mortality trends among heroin users treated between 1975 and 2013 in Northern Italy: Results of a longitudinal study. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017 Jun;77:166-173. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.02.009[↩]

- Drug Overdose Deaths: Facts and Figures. https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates[↩]

- Jones CM, Christensen A, Gladden RM. Increases in prescription opioid injection abuse among treatment admissions in the United States, 2004-2013. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017 Jul 1;176:89-95. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.03.011[↩]

- Irwin A, Jozaghi E, Weir BW, Allen ST, Lindsay A, Sherman SG. Mitigating the heroin crisis in Baltimore, MD, USA: a cost-benefit analysis of a hypothetical supervised injection facility. Harm Reduct J. 2017 May 12;14(1):29. doi: 10.1186/s12954-017-0153-2[↩]

- Boyer EW. Management of opioid analgesic overdose. N Engl J Med. 2012 Jul 12;367(2):146-55. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1202561[↩][↩]

- FDA Approves Higher Dosage of Naloxone Nasal Spray to Treat Opioid Overdose. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-higher-dosage-naloxone-nasal-spray-treat-opioid-overdose[↩]

- Coffin PO, Sullivan SD. Cost-effectiveness of distributing naloxone to heroin users for lay overdose reversal. Ann Intern Med. 2013 Jan 1;158(1):1-9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-1-201301010-00003. Erratum in: Ann Intern Med. 2017 May 2;166(9):687. doi: 10.7326/M17-0652[↩]

- What is Heroin? https://positivechoices.org.au/teachers/heroin-factsheet[↩]

- Gutstein HB, Akil H, in Goodman and Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics 10th edn, (eds Hardman JG & Limbird LE) Ch. 23 (McGraw-Hill, New York, 2001).[↩]

- Oldendorf WH, Hyman S, Braun LOS. Blood-brain barrier: penetration of morphine, codeine, heroin, and methadone after carotid injection. Science (80-) 1972;178:984–7.. doi: 10.1126/science.178.4064.984[↩]

- Ellis AD, McGwin G, Davis GG, Dye DW. Identifying cases of heroin toxicity where 6-acetylmorphine (6-AM) is not detected by toxicological analyses. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 2016 Sep;12(3):243-7. doi: 10.1007/s12024-016-9780-2[↩]

- Stein C. Opioid Receptors. Annu Rev Med. 2016;67:433-51. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-062613-093100[↩]

- Waldhoer M, Bartlett SE, Whistler JL. Opioid receptors. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:953-90. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073940[↩][↩]

- Johnson SW, North RA. Opioids excite dopamine neurons by hyperpolarization of local interneurons. J Neurosci. 1992 Feb;12(2):483-8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-02-00483.1992[↩]

- Goldstein A. Heroin addiction: neurobiology, pharmacology, and policy. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1991 Apr-Jun;23(2):123-33. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1991.10472231[↩]

- Cerebral hypoxia. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/001435.htm[↩]

- LaForge KS, Yuferov V, Kreek MJ. Opioid receptor and peptide gene polymorphisms: potential implications for addictions. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000 Dec 27;410(2-3):249-268. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00819-0. Erratum in: Eur J Pharmacol 2001 Aug 24;426(1-2):145.[↩]

- Kreek MJ, Bart G, Lilly C, LaForge KS, Nielsen DA. Pharmacogenetics and human molecular genetics of opiate and cocaine addictions and their treatments. Pharmacol Rev. 2005 Mar;57(1):1-26. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.1.1[↩]

- Wang X, Li B, Zhou X, Liao Y, Tang J, Liu T, Hu D, Hao W. Changes in brain gray matter in abstinent heroin addicts. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012 Dec 1;126(3):304-8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.05.030[↩]

- Ignar DM, Kuhn CM. Effects of specific mu and kappa opiate tolerance and abstinence on hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis secretion in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990 Dec;255(3):1287-95. https://jpet.aspetjournals.org/content/255/3/1287.long[↩]

- Kreek MJ, Ragunath J, Plevy S, Hamer D, Schneider B, Hartman N. ACTH, cortisol and beta-endorphin response to metyrapone testing during chronic methadone maintenance treatment in humans. Neuropeptides. 1984 Dec;5(1-3):277-8. doi: 10.1016/0143-4179(84)90081-7[↩]

- Li W, Li Q, Zhu J, Qin Y, Zheng Y, Chang H, Zhang D, Wang H, Wang L, Wang Y, Wang W. White matter impairment in chronic heroin dependence: a quantitative DTI study. Brain Res. 2013 Sep 19;1531:58-64. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.07.036[↩]

- Qiu Y, Jiang G, Su H, Lv X, Zhang X, Tian J, Zhuo F. Progressive white matter microstructure damage in male chronic heroin dependent individuals: a DTI and TBSS study. PLoS One. 2013 May 1;8(5):e63212. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063212[↩]

- Liu J, Qin W, Yuan K, Li J, Wang W, Li Q, Wang Y, Sun J, von Deneen KM, Liu Y, Tian J. Interaction between dysfunctional connectivity at rest and heroin cues-induced brain responses in male abstinent heroin-dependent individuals. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e23098. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023098[↩]

- Kreek MJ, Levran O, Reed B, Schlussman SD, Zhou Y, Butelman ER. Opiate addiction and cocaine addiction: underlying molecular neurobiology and genetics. J Clin Invest. 2012 Oct;122(10):3387-93. doi: 10.1172/JCI60390[↩]

- Volkow ND, Jones EB, Einstein EB, Wargo EM. Prevention and Treatment of Opioid Misuse and Addiction: A Review. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019 Feb 1;76(2):208-216. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3126[↩]

- Buprenorphine Quick Start Guide. https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/quick-start-guide.pdf[↩][↩]

- Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, Davoli M. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(2):CD002207. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002207.pub4[↩]

- How do medications to treat opioid use disorder work? https://nida.nih.gov/publications/research-reports/medications-to-treat-opioid-addiction/how-do-medications-to-treat-opioid-addiction-work[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Clinical Guidelines for the Use of Buprenorphine in the Treatment of Opioid Addiction. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); 2004. (Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 40.) Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK64245[↩]