Contents

- Mesenteric ischemia

- Mesenteric ischemia causes

- Mesenteric ischemia prevention

- Mesenteric ischemia symptoms

- Mesenteric ischemia complications

- Mesenteric ischemia diagnosis

- Mesenteric ischemia treatment

- Mesenteric ischemia prognosis

Mesenteric ischemia

Mesenteric vascular insufficiency also called mesenteric vascular disease or mesenteric ischemia is a condition that develops when there is a narrowing or blockage of one or more of the 3 major mesenteric arteries (i.e., celiac trunk, superior mesenteric artery [SMA] & inferior mesenteric artery [IMA]) that supply your small and large intestines, the blockage or reduced blood flow to part of your small and large intestines may lead to small or large intestines gangrene and perforation (puncture) 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7. Sudden loss of blood flow to your intestines also known as acute mesenteric ischemia from a blood clot requires immediate surgery 7. Mesenteric ischemia that develops over time also called chronic mesenteric ischemia. Chronic mesenteric ischemia is usually caused by a buildup of fatty deposits or plaque in your arteries. As plaque (fatty deposits) builds up inside your artery walls, the arteries can become hardened and narrowed (a process called atherosclerosis). Atherosclerosis affects up to 35 percent of Americans, and can cause narrowing (also called stenosis) of any of the arteries throughout your body. As atherosclerosis affects the whole body, people with mesenteric artery narrowing often have other heart and blood vessel conditions such as carotid artery disease and heart disease. In mesenteric artery disease, the arteries supplying blood to the intestines are narrowed; people with this condition lose weight and experience severe pain when they eat. Chronic mesenteric ischemia is treated with open surgery or a procedure called angioplasty 6. Untreated, chronic mesenteric ischemia can become acute mesenteric ischemia or lead to severe weight loss and malnutrition. However, chronic mesenteric ischemia often presents with vague abdominal pain that may be difficult to differentiate from other, more common causes of abdominal pain 8, 9, 10, 11.

The most common risk factors for acute mesenteric ischemia include:

- Atrial fibrillation (AF or AFib) — an irregular and often very rapid heart rhythm.

- Congestive heart failure — a condition in which the heart muscle doesn’t pump blood as well as it should.

- Recent vascular surgery.

The most common risk factors for chronic mesenteric ischemia include:

- Type 2 diabetes.

- High cholesterol levels.

- High blood pressure.

- Artery disease.

- Smoking.

- Obesity.

- Older age.

- Family history of atherosclerosis.

- Sedentary lifestyle.

Your doctor diagnoses mesenteric ischemia based on a combination of a physical examination, lab tests and imaging. Mesenteric vascular insufficiency diagnosis is typically made through abdominal duplex ultrasound (a combination of a traditional and Doppler ultrasound that assesses the blood vessels in your abdomen for blockages or aneurysms) or direct imaging of the artery with angiography. Imaging tests include CT scan, magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) or an arteriography, which can be used to determine the location and the extent of the disease.

Treatment of intestinal ischemia involves restoring the blood supply to your digestive tract. Options vary depending on the cause and severity of your condition.

If a blood clot causes a sudden loss of blood flow to your intestines also known as acute mesenteric ischemia, this is a medical emergency, you might require immediate surgery to treat your mesenteric ischemia. Treatment can include medicines to dissolve the blood clots and open up the mesenteric arteries. If the problem is severe, the blockage is removed and the mesenteric arteries are reconnected to the aorta. A bypass around the blockage is another procedure. It is usually done with a plastic tube graft. A stent may be used as an alternative to surgery to enlarge the blockage in the artery or to deliver medicine directly to the affected area. This is a new technique and it should only be done by experienced vascular surgeons. The outcome is usually better with surgery.

At times, a portion of your intestine will need to be removed.

Mesenteric ischemia that develops over time also called chronic mesenteric ischemia might be treated with angioplasty. Balloon angioplasty is a procedure that uses a balloon to open the narrowed artery. In some cases, it may be necessary to place a stent (a wire-mesh tube that expands to hold the artery open). The stent is left permanently in the artery to provide a reinforced channel for blood flow.

People with acute mesenteric ischemia often do poorly because parts of the intestine may die before surgery can be done. This can be fatal. However, with prompt diagnosis and treatment, acute mesenteric ischemia can be treated successfully.

The prognosis for chronic mesenteric ischemia is good after a successful surgery. However, it is important to make lifestyle changes to prevent hardening of your arteries from getting worse. People with hardening of the arteries that supply the intestines often have the same problems in blood vessels that supply the heart, brain, kidneys, or legs.

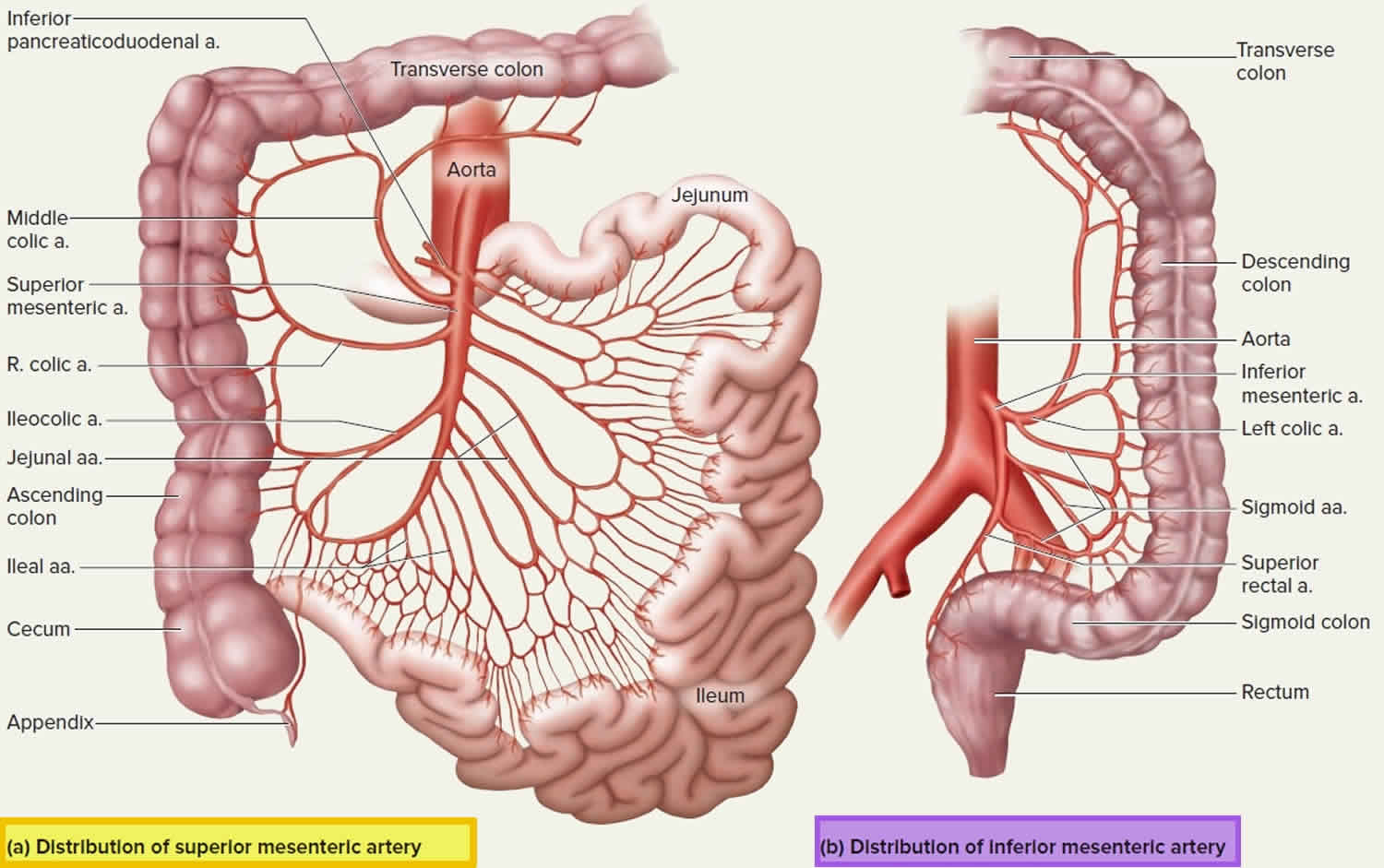

Figure 1. Mesenteric artery

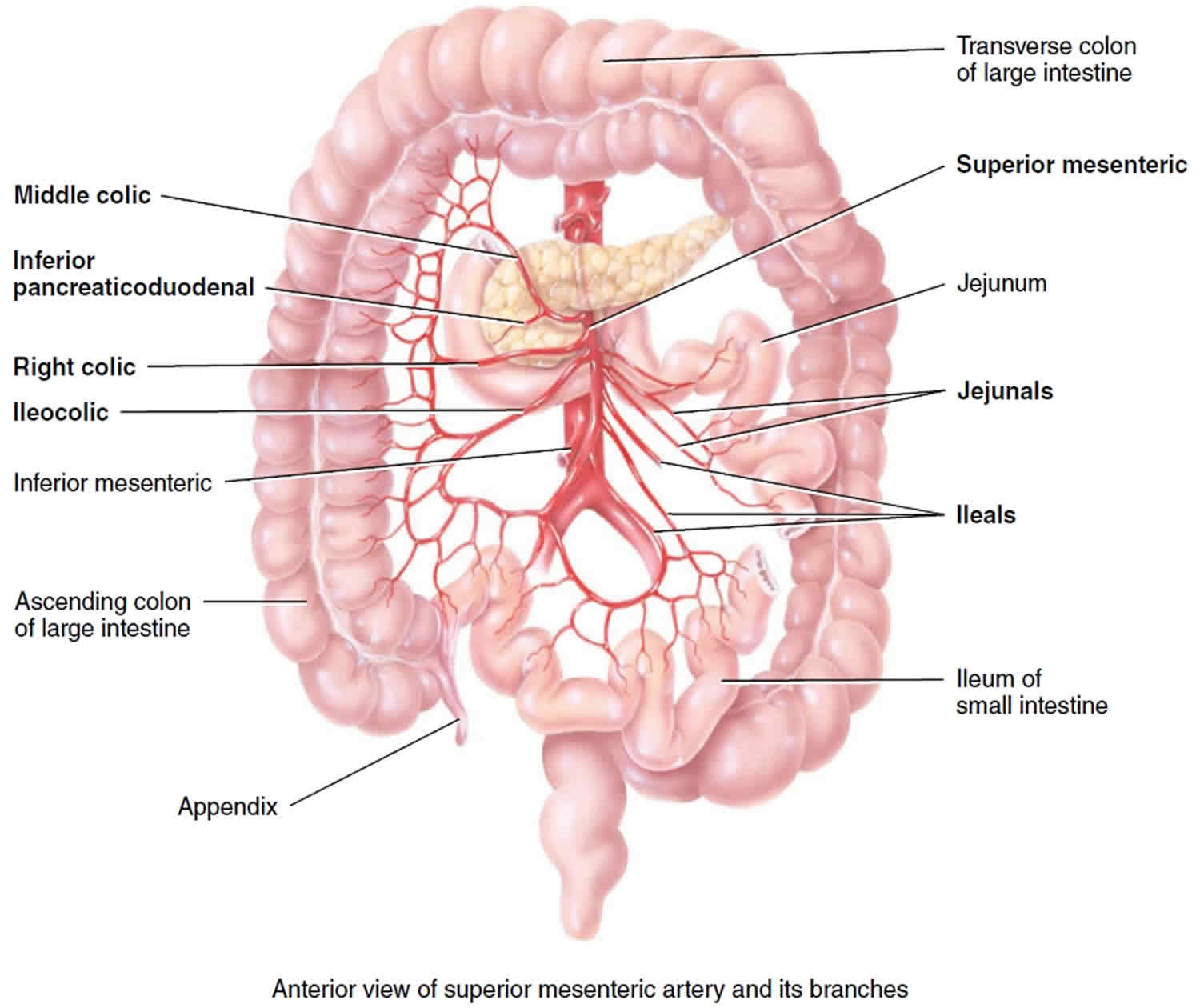

Figure 2. Superior mesenteric artery and its branches

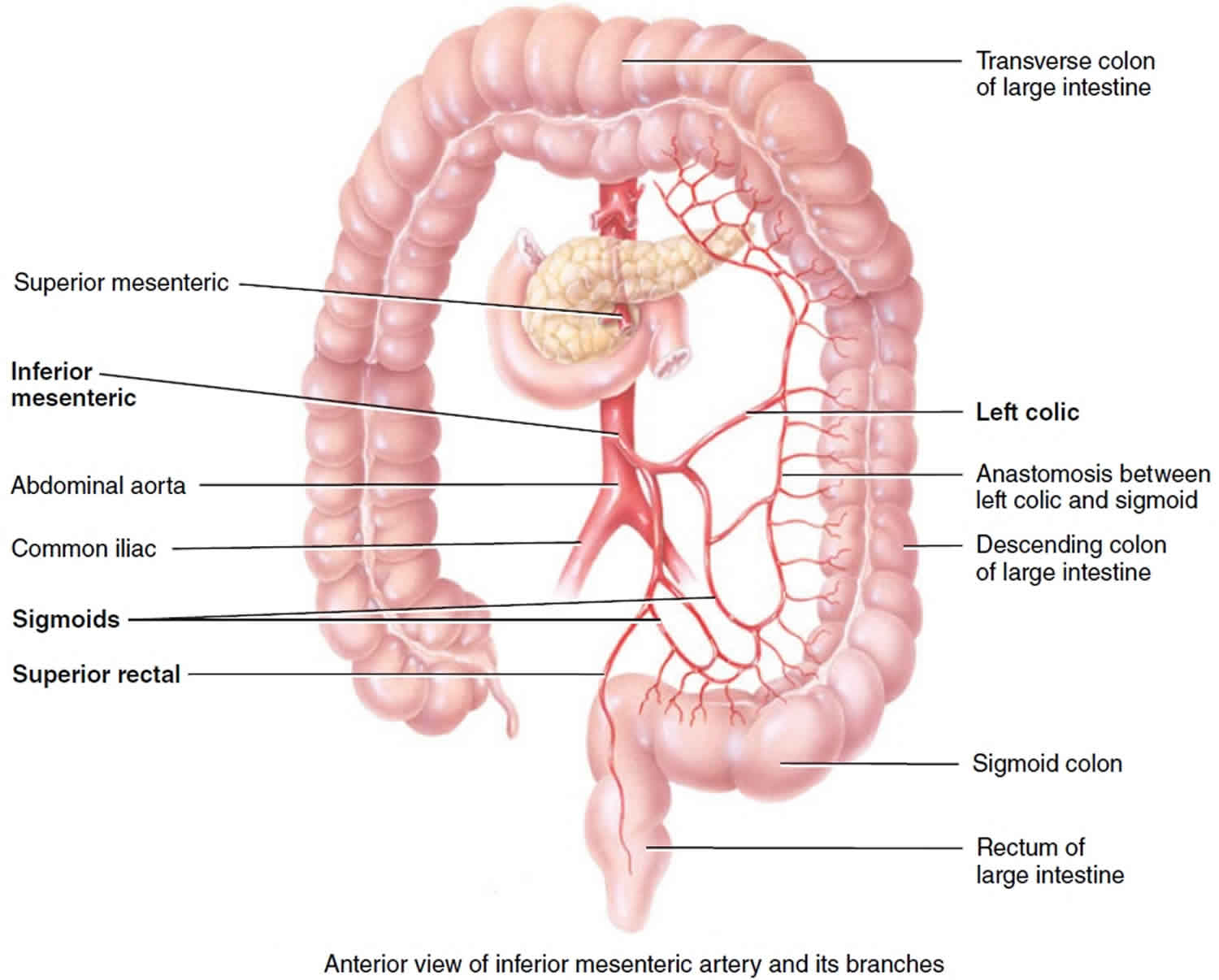

Figure 3. Inferior mesenteric artery and its branches

Is mesenteric ischemia treatable or curable?

Mesenteric ischemia is treatable and reversible when it’s caught early enough.

The first priority is always to restore circulation as quickly as possible. Because mesenteric ischemia becomes more dangerous over time, healthcare providers may recommend surgery more quickly.

After restoring blood flow, the next priority is checking to see if there’s any damaged or dead tissue. In cases where sections of your intestine or colon are dead because they didn’t have enough blood flow, removing those sections is the only way to fix the damage and prevent life-threatening complications.

Mesenteric ischemia causes

Both acute and chronic mesenteric ischemia are caused by a decrease in blood flow to the small and large intestines. Acute mesenteric ischemia is most commonly caused by a blood clot in the main mesenteric artery. The blood clot often starts in the heart. Chronic mesenteric ischemia is most commonly caused by a buildup of fatty deposits, called plaque, that narrows the arteries.

The arteries that supply blood to your intestines run directly from the aorta. The aorta is the main artery from your heart. Hardening of the arteries occurs when fat, cholesterol, and other substances build up in the walls of arteries. This is more common in smokers and in people with high blood pressure or high blood cholesterol. This narrows the blood vessels and reduces blood flow to the intestines. Like every other part of the body, blood brings oxygen to the intestines. When the oxygen supply is slowed, symptoms may occur.

3 major vessels serve the abdominal contents:

- Celiac trunk: Supplies the esophagus, stomach, proximal duodenum, liver, gallbladder, pancreas, and spleen

- Superior mesenteric artery (SMA): Supplies the distal duodenum, jejunum, ileum, and colon to the splenic flexure (see Figures 1 and 2)

- Inferior mesenteric artery (IMA): Supplies the descending colon, sigmoid colon, and rectum (see Figures 1 and 3)

Collateral vessels are abundant in the stomach, duodenum, and rectum; these areas rarely develop ischemia. The splenic flexure is a watershed between the superior mesenteric artery and inferior mesenteric artery and is at particular risk of ischemia. Note that acute mesenteric ischemia is distinct from ischemic colitis, which involves only small vessels and causes mainly mucosal necrosis and bleeding.

Mesenteric blood flow may be disrupted on either the venous or arterial sides. In general, patients > 50 are at greatest risk and have the types of occlusions and risk factors. However, many patients have no identifiable risk factors.

The blood supply to the intestines may be suddenly blocked by a blood clot (embolus). The clots most often come from the heart or aorta. These clots are more commonly seen in people with abnormal heart rhythm.

Both acute and chronic mesenteric ischemia are caused by a decrease in blood flow to your intestines. Acute mesenteric ischemia is most commonly caused by a blood clot in the main mesenteric artery. The blood clot often originates in the heart. The chronic form is most commonly caused by a buildup of plaque that narrows the mesenteric arteries.

Mesenteric ischemia has multiple causes. The most common are:

- Mesenteric Arterial Embolism (> 40%): Arterial embolism is a blood clot or piece of atherosclerotic plaque material (the buildup of cholesterol and other fatty materials in an artery) that travels from its origin in the heart or aorta to lodge in the smaller arteries (in this case those of the intestines). Predisposing factors include cardiomyopathy, atrial fibrillation, recent angiography, underlying vasculitis and valvular disorders.

- Mesenteric Arterial Thrombosis (30%): Arterial thrombus is a blood clot that forms spontaneously in the arteries or veins, including those of the intestines, blocking flow 12. Predisposing factors include patients with atherosclerosis, peripheral arterial disease, hypercoagulability, estrogen therapy, and prolonged hypotension.

- Mesenteric Venous Thrombosis (15%). Mesenteric venous thrombosis causes increases in the resistance of mesenteric venous blood flow. Patients who have local intra-abdominal inflammatory processes (such as inflammatory bowel disease) are at higher risk for this. Patients who are hypercoagulable (in other words those with heritable and acquired thrombophilias and malignancies) are also at a higher risk.

- Nonocclusive Mesenteric Ischemia (NOMI) (15%): Sometimes flow is not blocked completely but is simply too low because of low heart output (as in heart failure or shock), “spasm” of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) or because certain drugs (such as cocaine) narrow the blood vessels 13. In general, people older than 50 years are at greatest risk. Risk factors include peripheral artery disease, septic shock, vasoconstrictive medications (such as digoxin), cocaine abuse, hemodialysis, among many other conditions.

Blockage of blood flow for more than 6 hours can cause the affected area of intestine to die, allowing intestinal bacteria to invade the person’s system. Shock, organ failure, and death are likely if intestinal death occurs.

Risk factors for mesenteric ischemia

- Arterial embolus (> 40%): Coronary artery disease, heart failure, valvular heart disease, atrial fibrillation, history of arterial emboli

- Arterial thrombosis (30%): Generalized atherosclerosis. If you’ve had other conditions caused by atherosclerosis you have an increased risk of intestinal ischemia. These conditions include decreased blood flow to your heart (coronary artery disease), legs (peripheral vascular disease) or the arteries supplying your brain (carotid artery disease).

- Venous thrombosis (15%): Hypercoagulable states, inflammatory conditions (eg, pancreatitis, diverticulitis), trauma, heart failure, renal failure, portal hypertension, decompression sickness

- Nonocclusive ischemia (15%): Low-flow states (eg, heart failure, shock, cardiopulmonary bypass), splanchnic vasoconstriction (eg, vasopressors, cocaine)

- Age. People older than 50 are more likely to develop intestinal ischemia.

- Smoking. Cigarettes and other forms of smoked tobacco increase your risk of intestinal ischemia.

- Heart and blood vessel problems. Your risk of intestinal ischemia is increased if you have congestive heart failure or an irregular heartbeat such as atrial fibrillation. Blood vessel diseases that result in irritation and inflammation of veins and arteries (vasculitis) may also increase risk.

- Medications. Certain medications may increase your risk of intestinal ischemia. Examples include birth control pills and medications that cause your blood vessels to expand or contract, such as some allergy medications and migraine medications.

- Blood-clotting problems. Diseases and conditions that increase your risk of blood clots may increase your risk of intestinal ischemia. Examples include sickle cell anemia and the Factor V Leiden mutation.

- Other health conditions. For example, having high blood pressure, diabetes or high cholesterol can increase the risk of intestinal ischemia.

- Recreational drug use. Cocaine and methamphetamine use have been linked to intestinal ischemia.

Acute mesenteric ischemia

Acute mesenteric ischemia is the result of a sudden loss of blood flow to your intestines. Decreased blood flow can permanently damage the small intestine.

Acute mesenteric ischemia may be due to:

- A blood clot (embolus) that comes loose from your heart and travels through your bloodstream to block an artery. It usually blocks the superior mesenteric artery, which supplies oxygen-rich blood to your intestines. This is the most common cause of acute mesenteric artery ischemia. This type can be brought on by congestive heart failure, an irregular heartbeat (arrhythmia) or a heart attack.

- A blockage that develops within one of the main intestinal arteries and slows or stops blood flow. This often is a result of buildup of fatty deposits in your arteries (atherosclerosis). This type of sudden ischemia tends to occur in people with chronic intestinal ischemia.

- Impaired blood flow resulting from low blood pressure due to shock, heart failure, certain medications or chronic kidney failure. This is more common in people who have other serious illnesses and who have some degree of atherosclerosis. This type of acute mesenteric ischemia is often referred to as nonocclusive ischemia, which means that it’s not due to a blockage in the artery.

The most common risk factors for acute mesenteric ischemia include:

- Atrial fibrillation (AF or AFib) — an irregular and often very rapid heart rhythm.

- Congestive heart failure — a condition in which the heart muscle doesn’t pump blood as well as it should.

- Recent vascular surgery.

Chronic mesenteric ischemia

Chronic mesenteric ischemia results from the buildup of fatty deposits on an artery wall (atherosclerosis). The atherosclerosis process is generally gradual. It’s also known as intestinal angina because it results in decreased blood flow to the intestines after eating. You may not require treatment until at least two of the three major arteries supplying your intestines become severely narrowed or completely blocked.

A possibly dangerous complication of chronic mesenteric ischemia is developing a blood clot within a narrowed artery. This can cause blood flow to be suddenly blocked, resulting in acute mesenteric ischemia.

The most common risk factors for chronic mesenteric ischemia include:

- Type 2 diabetes.

- High cholesterol levels.

- High blood pressure.

- Artery disease.

- Smoking.

- Obesity.

- Older age.

- Family history of atherosclerosis.

- Sedentary lifestyle.

Mesenteric ischemia prevention

The following lifestyle changes can reduce your risk for narrowing of the arteries:

- Get regular exercise.

- Follow a healthy diet.

- Get heart rhythm problems treated.

- Keep your blood cholesterol and blood sugar under control.

- Quit smoking.

Mesenteric ischemia symptoms

Signs and symptoms of intestinal ischemia can develop suddenly (acute) or gradually (chronic). Signs and symptoms may be different from one person to the next, but there are some generally recognized patterns that suggest mesenteric ischemia.

At first, the person has severe abdominal pain, usually developing suddenly, but only mild pain occurs when the doctor presses on the abdomen during the examination (unlike in disorders such as appendicitis or diverticulitis, in which pressing makes the pain much worse). Later, as the intestine starts to die, the doctor’s examination of the abdomen causes more severe pain.

Acute mesenteric ischemia symptoms

Symptoms of sudden acute mesenteric ischemia due to a traveling blood clot include:

- Sudden severe abdominal pain. Sudden severe abdominal pain is the most common, happening in about 75% to 80% of cases. This usually happens after eating, isn’t in a specific place in your belly and can be very severe. In many cases, the pain is much worse than your healthcare provider might expect based on their examination.

- Diarrhea. Diarrhea happens in about 40% of cases, but it may happen off and on rather than consistently. Diarrhea may also be very intense, and severe pain can follow. In the late stages of this condition, bloody diarrhea is more common.

- Nausea and vomiting. Vomiting is especially common, happening in about 70% of cases.

- Urgent need to have a bowel movement

- Frequent, forceful bowel movements

- Abdominal tenderness or bloating (distention)

- Fever. This can be a sign of a dangerous infection.

- Blood in your stool

- Mental confusion in older adults

- Weight loss.This symptom happens often, even in acute cases. It can indicate avoiding food because of pain or other symptoms that happen before this condition reaches a severe level.

Patients with acute mesenteric ischemia may initially present with classic “pain out of proportion to examination”, with an epigastric bruit; many, however, do not 14. Other patients may have tenderness with palpation on examination owing to peritoneal irritation caused by full-thickness bowel injury. This finding may lead the physician to consider diagnoses other than acute mesenteric ischemia 15. In a patient with abdominal pain of acute onset, it is critical to assess the possibility of atherosclerotic disease and potential sources of an embolus, including a history of atrial fibrillation and recent myocardial infarction 16. During the examination, the patient’s description of the history and symptoms can be unclear because of changes in mental status, particularly if he or she is elderly 17.

Differentiation between arterial and venous obstruction is not always simple; however, patients with mesenteric venous thrombosis, as compared with those with acute arterial occlusion, tend to present with a less abrupt onset of abdominal pain 18. Risk factors for venous thrombosis that should be evaluated include a history of deep venous thrombosis, cancer, chronic liver disease or portal-vein thrombosis, recent abdominal surgery, inflammatory disease, and thrombophilia 1.

Chronic mesenteric ischemia symptoms

Symptoms caused by chronic mesenteric ischemia due to gradual hardening of the mesenteric arteries include:

- Abdominal cramps or fullness, usually within 30 minutes after eating. The pain often feels similar to cramps and usually happens in the upper belly area or around your navel (belly button).

- Pain that worsens over an hour

- Pain that goes away within one to three hours

- Diarrhea. Diarrhea in about one-third of people with this condition, and is usually chronic (meaning it happens over a long period of time).

- Nausea and vomiting

- Abdominal pain that gets gradually worse over weeks or months

- Fear of eating because of pain that happens after eating. As chronic mesenteric ischemia gets worse, the pain becomes more intense. That can cause “food fear,” which is when you want to avoid food because you anticipate pain after eating. This usually leads to unintentional weight loss.

- Unintended weight loss

- Bloating

Patients with chronic mesenteric ischemia can present with a variety of symptoms, including abdominal pain, postprandial pain, nausea or vomiting (or both), early satiety, diarrhea or constipation (or both), and weight loss 1. A detailed inquiry into the abdominal pain and its relationship to eating can help with the diagnosis. Abdominal pain 30 to 60 minutes after eating is common 19 and is often self-treated with food restriction, resulting in weight loss and, in extreme situations, fear of eating, or “food fear”. Postprandial pain may, however, be associated with other intraabdominal processes, including biliary disease, peptic ulcer disease, pancreatitis, diverticular disease, gastric reflux, irritable bowel syndrome, and gastroparesis.

An extensive gastroenterologic workup, possibly including cholecystectomy and upper and lower endoscopy — tests that are often negative in patients with chronic mesenteric ischemia — is generally carried out before the diagnosis is made 1. An important distinction is that many of these alternative processes do not involve weight loss, whereas it is common in cases of mesenteric ischemia 19, 20. Since older age and a history of smoking are common in these patients, cancer is often considered, and concern about it may delay the identification of chronic mesenteric ischemia 1. Furthermore, particularly in the case of elderly women with a history of weight loss, dietary changes, and systemic vascular disease, chronic mesenteric ischemia must be seriously considered and evaluated appropriately 1.

Mesenteric ischemia complications

If not treated promptly, acute mesenteric ischemia can lead to:

- Sepsis. This potentially life-threatening condition is caused by the body releasing chemicals into the bloodstream to fight infection. In sepsis, the body overreacts to the chemicals, triggering changes that can lead to multiple organ failure.

- Irreversible bowel damage. Insufficient blood flow to the bowel can cause parts of the bowel to die (gangrene).

- Death. Both of the above complications can lead to death.

People with chronic mesenteric ischemia can develop:

- Fear of eating. This occurs because of the after-meal pain associated with the condition.

- Unintentional weight loss. This can occur as a result of the fear of eating.

- A hole through the wall of the intestines (perforation). A perforation can develop, which can cause the contents of the intestine to leak into the abdominal cavity. This may cause a serious infection (peritonitis).

- Scarring or narrowing of your intestine. Sometimes the intestines can recover from ischemia, but as part of the healing process the body forms scar tissue that narrows or blocks the intestines. This occurs most often in the colon. Rarely this happens in the small intestines.

- Acute-on-chronic mesenteric ischemia. Symptoms of chronic mesenteric ischemia can progress, leading to the acute form of the condition.

Mesenteric ischemia diagnosis

Your doctor diagnoses mesenteric ischemia based on a combination of a physical examination, lab tests and imaging.

If the person has typical symptoms of acute mesenteric ischemia or if the abdomen is very tender, doctors usually take the person to surgery straight away.

If you have pain after eating that causes you to limit food and lose weight, your doctor might suspect that you have chronic mesenteric ischemia.

If the diagnosis of acute mesenteric ischemia is not clear, doctors do CT angiography (a special CT scan using radiopaque dye injected in an arm vein to produce images of blood vessels) to look for swelling of the intestines or blockages in the arteries that supply blood to the intestines 14, 21, 22. In addition to providing information about the vasculature, CT angiography (CTA) can indicate potential sources of emboli, other intraabdominal structures and pathologic processes, and abnormal findings such as the lack of enhancement or the thickening of the bowel wall and mesenteric stranding associated with diminished blood flow. More ominous pathological findings, including pneumatosis, free intraabdominal air, and portal venous gas, may also be noted 23.

Catheter angiography, which was previously considered to be the standard method of diagnosis of mesenteric ischemia, has become a component of initial therapy. Catheter angiography with selective catheterization of mesenteric vessels is now used once a plan for revascularization has been chosen. Single or complementary endovascular therapies, including thrombolysis 24, angioplasty with or without stenting 25 and intraarterial vasodilation 26 are then combined to restore blood flow. Catheter angiography can also be used to confirm the diagnosis before open abdominal exploration is undertaken 14

In some cases, you may need surgery to find and remove damaged tissue. Opening the abdomen allows diagnosis and treatment during one procedure.

Despite the many investigations conducted to date, there are no specific blood tests to indicate intestinal ischemia 27, 28. Tests for markers of nutritional status, such as albumin, transthyretin, transferrin, and C-reactive protein, are the only studies of value in cases of chronic mesenteric ischemia, since they can be used to assess the degree of malnutrition before revascularization is undertaken.

Mesenteric ischemia treatment

If mesenteric ischemia is diagnosed during surgery, the blood vessel blockage can sometimes be removed or bypassed, but other times the affected intestine must be removed.

If mesenteric ischemia is diagnosed during CT angiography, doctors may try to relieve the blockage in the blood vessels using angiography. In angiography, a small flexible tube (catheter) is threaded through the artery in the groin and into the arteries of the intestines. If a blockage is seen during angiography, sometimes it can be opened by injecting certain drugs, suctioning out a blood clot using a special angiography catheter, or inflating a small balloon within the artery to widen it and then placing a small tube or manufactured mesh (stent) to keep it open. If doctors cannot successfully open the blockage using these procedures, the person needs surgery to open the blockage or to remove the affected portion of the intestine.

Patients with acute mesenteric ischemia require intensive care and should be placed in the hospital’s intensive care unit after surgery. Most patients require a “second-look laparotomy” 24 to 48 hours after mesenteric revascularization, as it is important to re-evaluate the bowel. Unless contraindicated, many people need to be on long-term systemic anticoagulation prevent blood clotting after their hospital stay. If a mesenteric artery stent is placed, it is important to have periodic surveillance of the stent (either with duplex ultrasound or CT angiography), although there have been few studies done on specific surveillance intervals.

Early medical therapy

Fluid resuscitation with the use of isotonic crystalloid fluids and blood products as needed is a critical component of initial care. Serial monitoring of electrolyte levels and acid–base status should be performed, and invasive hemodynamic monitoring should be implemented early 14; this is especially true in patients with acute mesenteric ischemia, in whom severe metabolic acidosis and hyperkalemia can develop as a result of infarction 29. These conditions may create the potential for rapid decompensation to a systemic inflammatory response or progression to sepsis.

In patients with hemodynamic instability, it is imperative to carefully adjust fluid volume while avoiding fluid overload and to use pressor agents only as a last resort. The fluid-volume requirement can be very high, especially after revascularization, because of the extensive capillary leakage; as much as 10 to 20 liters of crystalloid fluid may be required during the first 24 hours after the intervention 30.

Heparin treatment should be initiated as soon as possible in patients who have acute mesenteric ischemia or an exacerbation of chronic mesenteric ischemia. Vasodilators may play a role in care, particularly in combating persistent vasospasm in patients with acute ischemia after revascularization 31. Epithelial permeability increases during acute mesenteric ischemia as high bacterial antigen loads trigger inflammatory pathways 32, 33 and the risk of bacterial translocation and sepsis increases 34.

Antibiotics can lead to resistance and alterations in bacterial flora; however, their use has been associated with improved outcomes in critically ill patients 35, 36. In general, the high risk of infection among patients with acute mesenteric ischemia outweighs the risks of antibiotic use, and therefore broad-spectrum antibiotics should be administered early in the course of treatment.

Oral intake should be avoided in patients with acute mesenteric ischemia, since it can exacerbate intestinal ischemia 37. In patients with chronic mesenteric ischemia, in contrast, enteral nutrition (as long as it does not cause pain) or parenteral nutrition should be considered in order to improve perfusion by means of mucosal vasodilation and to provide nutritional and immunologic benefits 38.

Acute mesenteric artery ischemia treatment

The most effective treatment for acute mesenteric ischemia is surgery. Surgery may be necessary to remove a blood clot, to bypass an artery blockage, or to repair or remove a damaged section of intestine. If angiography is done to diagnose the problem, it may be possible to remove a blood clot or to open up a narrowed artery with angioplasty at the same time. Your surgeon can also place a stent, a support frame device that holds a section of blood vessel wide open.

In cases where it isn’t possible to restore blood flow directly, your surgeon can take a section of blood vessel from another place in your body and use it to create a bypass. That bypass restores blood flow by making a detour around a previously blocked area.

After restoring blood flow, your surgeon can check nearby tissue for signs of damage. If they find dead or damaged areas, your surgeon can remove them and repair the surrounding area so it can function normally in the future. In many cases, this involves a second surgery because it can take up to two days before some dead or damaged tissue is visible. If part of your small or large intestine has started to die and can’t be saved, it may need to be removed.

Treatment also may include antibiotics and medications to prevent clots from forming, dissolve clots or dilate blood vessels:

- Intravenous (IV) fluids. These can help in cases where low blood pressure or dehydration are part of the issue.

- Blood transfusions. These are especially important with sufficient blood loss.

- Oxygen. This reduces how hard your body has to work to circulate blood.

- Antibiotics. These are crucial with any kind of intestinal or colon surgery because of the risk of infections from the bacteria normally found in those organs.

- Blood thinners. These medications keep clots from forming, preventing not only a repeat of mesenteric ischemia, but also heart attacks, strokes and pulmonary embolisms. However, people at risk for dangerous bleeding might not receive blood thinners.

Endovascular procedures

Endovascular procedures can theoretically restore perfusion more rapidly than can open repair and may thus prevent progression of mesenteric ischemia to bowel necrosis. Although the use of endovascular techniques is becoming more common, the comparative data on the results with the two approaches in patients with acute mesenteric ischemia are insufficient to show a clear advantage of one approach over the other 39, 40, 41.

The largest review of endovascular interventions involved 70 patients with acute mesenteric ischemia. Treatment was considered to be successful in 87% of the patients, and in-hospital mortality was lower among those who underwent endovascular procedures than among those who underwent open surgery (36% vs. 50%). However, patients who presented with more profound visceral ischemia may have been assigned to open revascularization. These and other data 40, 42 suggest that the use of endovascular procedures for acute mesenteric ischemia is becoming more common; the use of these procedures increased from 12% of cases in 2005 to 30% of cases in 2009 43. These data also show that endovascular intervention may be most appropriate for patients with mesenteric ischemia that is not severe and those who have severe coexisting conditions that place them at high risk for complications and death associated with open surgery.

An acute occlusion can be treated with a combination of endovascular interventions, with initial treatment aimed at rapidly restoring perfusion to the viscera, most often by means of mechanical thrombectomy or angioplasty and stenting. Thrombolysis is safe and very effective as an adjunct procedure to remove the additional burden of thrombus in patients without peritonitis, and it can be especially helpful in restoring perfusion to occluded arterial branches. These techniques can be effective in treating both embolic and thrombotic occlusions 44, 25. Although the use of endovascular therapy for acute mesenteric ischemia precludes direct assessment of bowel viability, 31% of patients who received endovascular therapy in one series were spared laparotomy 25. If endovascular-only therapy is pursued, close monitoring is compulsory, and any evidence of clinical deterioration or peritonitis necessitates operative exploration performed on an emergency basis because 28 to 59% of these patients will ultimately require bowel resection 25, 42.

Open surgical repair

The goals of open surgical repair for acute mesenteric ischemia are to revascularize the occluded vessel, assess the viability of the bowel, and resect the necrotic intestine 45. Emboli that cause acute occlusion typically lodge within the proximal superior mesenteric artery and have a good response to surgical embolectomy. If embolectomy is unsuccessful, arterial bypass may be performed. This procedure is ideally carried out with autologous grafting, typically of a single vessel distal to the occlusion. However, if distal perfusion remains impaired, local intraarterial doses of thrombolytic agents can be administered.

A hybrid option, retrograde open mesenteric stenting, involves local thromboendarterectomy and angioplasty, followed by retrograde stenting 46, 47. This approach reduces the extent of surgery while allowing for direct assessment of the bowel. At this time, however, it is not commonly used, and evidence regarding its outcomes is limited 48.

After revascularization, the bowel and other intraabdominal organs are assessed for viability and evidence of ischemia. Frankly ischemic bowel is resected, whereas areas that suggest the possible presence of ischemia may be left for evaluation at a follow-up, or “second-look,” operation. Up to 57% of patients ultimately require further bowel resection 49, 42, 39, including nearly 40% of patients who undergo a second-look operation 49, 14. Short-term mortality after open revascularization ranges from 26 to 65% and rates are higher among patients with renal insufficiency, older age, metabolic acidosis, a longer duration of symptoms, and bowel resection at the time of a second-look operation 39, 25, 49, 50.

Chronic mesenteric artery ischemia treatment

Treatment requires restoring blood flow to your intestine. Your surgeon can bypass the blocked arteries or widen narrowed arteries with angioplasty or by placing a stent in the artery. Balloon angioplasty and other catheter-based procedures are often considered with chronic mesenteric artery ischemia. In many cases, doctors will recommend catheter-based procedures over surgery whenever possible. That’s because surgery is harder on your body, and it’s easier to recover from a catheter procedure. However, surgery for chronic mesenteric artery ischemia is common, especially when it involves a slow-growing clot or blood vessels that have become too narrow. Surgery is also more likely to happen when a person has internal bleeding, infections or sepsis, or other dangerous complications. Bypass surgery is also possible when other options can’t restore blood flow.

Decisions regarding the most appropriate approach to patients with chronic mesenteric ischemia should weigh the morphologic features of the lesion and the patient’s state of health against the short- and long-term risks and benefits of the procedure. In most centers, endovascular therapy is considered to be first-line therapy, particularly in patients with short, focal lesions. The risks associated with future reintervention may outweigh the immediate risks of open surgery among most patients with chronic mesenteric ischemia. In contrast, open repair may be a preferable option for younger, lower-risk patients with a longer life expectancy or for those whose lesions are not amenable to endovascular techniques.

Open repair, which was formerly considered to be the standard in such cases, has been surpassed in recent years by endovascular repair, which is now used in 70 to 80% of initial procedures 42. Because angioplasty alone has poor patency and is associated with poor long-term symptom relief, stenting is used most often 51, 52. Open repair can be performed with the use of antegrade inflow (from the supraceliac aorta) or retrograde inflow (from the iliac artery), with either a vein or prosthetic conduit to bypass one or more vessels, depending on the extent of disease. Hybrid procedures involving open access to the superior mesenteric artery and retrograde stenting, are also options.

Endovascular repair is a very successful, minimally invasive approach that provides initial relief of symptoms in up to 95% of patients and has a lower rate of serious complications than open repair 52. Despite these advantages, the use of endovascular techniques is associated with lower rates of long-term patency and a shorter time to the return of symptoms 51, 53, 54. Restenosis occurs in up to 40% of patients, and among these patients, 20 to 50% will require reintervention 55, 56. Open repair is associated with slower recovery and longer hospital stays than endovascular repair. Data on mortality are inconsistent; however, patients treated with open repair have improved rates of symptom relief at 5 years and of primary patency (both rates are as high as 92%) and lower rates of reintervention 54, 57, 58, 59.

Mesenteric venous thrombosis treatment

If your intestine shows no signs of damage and unless systemic anticoagulation is contraindicated, you’ll likely need to take anticoagulant medication for about 3 to 6 months. Anticoagulants help prevent clots from forming. In most cases, anticoagulation is the only therapy necessary; rates of recurrence and death are lower among patients who receive anticoagulation than among those who do not 60. The condition of approximately 5% of patients who receive conservative treatment will deteriorate, and further intervention will be required 61. Options for intervention in patients in whom medical treatment alone is unsuccessful include transhepatic and percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy 62, thrombolysis 24 and open intraarterial thrombolysis 63. The few studies of the outcomes of these interventions have shown technical success with low risks of complications and death, although outcomes may be affected by the selection of patients and the timing of the intervention 24.

You might need a procedure to remove the clot. If parts of your intestine show signs of damage, you might need surgery to remove the damaged section. If tests show you have a blood-clotting disorder, you may need to take anticoagulants for the rest of your life.

As in all cases of mesenteric ischemia, any evidence of peritonitis, stricture, or gastrointestinal bleeding should trigger an exploratory laparotomy to assess for the possibility of bowel necrosis and the need for a second-look operation.

Non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia (NOMI) treatment

The initial goal of treatment is to address hemodynamic instability. Additional treatment may include systemic anticoagulation and the use of vasodilators in patients who do not have bowel infarction. Catheter-directed infusion of vasodilatory and antispasmodic agents, most commonly papaverine hydrochloride, can be used 64. Patients should be monitored closely by means of serial abdominal examinations, and open surgical exploration should be performed if there is concern about the possibility of peritonitis.

If there is evidence of severe colonic ischemia, your health care provider may recommend antibiotics to treat or prevent infections. Treating any underlying medical condition, such as congestive heart failure or an irregular heartbeat, is also important.

You’ll likely need to stop medications that constrict your blood vessels, such as migraine drugs, hormone medications and some heart drugs. In most cases, colon ischemia heals on its own.

If your colon has been severely damaged, you may need surgery to remove the dead tissue. In some cases, you may need surgery to bypass a blockage in one of your intestinal arteries. If angiography is done to diagnose the problem, it may be possible to open up a narrowed artery with angioplasty.

Angioplasty involves using a balloon inflated at the end of a catheter to compress the fatty deposits and stretch the artery, making a wider path for the blood to flow. A spring-like metallic tube (stent) also may be placed in your artery to help keep it open. A blood clot may be removed or be treated with medication to dissolve the clot.

How soon after treatment will I feel better and recover?

With quick diagnosis and treatment, most people will start to feel better when blood flow to the affected area improves. Others will likely start to feel better within days or weeks.

For those who undergo surgery, it usually takes longer for them to feel better and recover. That’s because surgery is a more intense procedure and recovery takes time.

When can I go back to work/school?

Your doctor can best explain the likely timeline of your recovery. Depending on the severity of your case and the treatments involved, many people can return to most or all of their usual activities within days or weeks. In more severe cases, especially those involving surgery, it may take longer.

Follow-up care

The long-term care of patients with mesenteric ischemia is focused on managing coexisting conditions and risk factors. Therefore, smoking-cessation measures, blood-pressure control, and statin therapy are recommended. Lifelong preventive treatment with aspirin is recommended in all patients who undergo endovascular or open repair 1. Patients who undergo endovascular repair should also receive clopidogrel for 1 to 3 months after the procedure 1. Regardless of the type of repair performed, in patients with atrial fibrillation, mesenteric venous thrombosis, or inherited or acquired thrombophilia, oral anticoagulant therapy is indicated and should be continued indefinitely or until the underlying cause of embolism or thrombosis has resolved 1.

Nutritional status and body weight should be monitored in all patients who have undergone an intervention for mesenteric ischemia. These patients may have prolonged ileus and food fear, and they may require total parenteral nutrition until full oral intake is possible 1. In patients who require bowel resection, diarrhea and malabsorption may occur. Extensive nutritional support, lifelong total parenteral nutrition, or even evaluation for small-bowel transplantation may be required in patients with persistent short-gut syndrome.

Because the recurrence of symptoms is common in patients with a history of mesenteric ischemia, lifelong repeated assessment of vascular patency is indicated 1. Duplex ultrasonography should be performed every 6 months for the first year after repair, then yearly thereafter 1. All patients should be informed about the risks and warning signs of stenosis, occlusion, and repeated episodes of ischemia. Any recurrence of symptoms should prompt diagnostic imaging. Given the high morbidity and mortality associated with acute mesenteric ischemia, preemptive revascularization is advised if evidence of recurrent stenosis or occlusion is identified 1.

Mesenteric ischemia prognosis

Even though survival of patients following mesenteric artery ischemia has improved over the past 3 decades, mesenteric ischemia still carries a very high morbidity and mortality. Mortality is estimated to be 60% to 80%, especially in those with more than a 24-hour delay in diagnosis. Early recognition of the problem can help reduce the mortality 65, 66. If the doctor can make the diagnosis and begin treatment early, people usually recover well. People with acute mesenteric ischemia often do poorly because parts of the intestine may die before surgery can be done. This can be fatal. However, with prompt diagnosis and treatment, acute mesenteric ischemia can be treated successfully. Depending on the time of presentation and treatment, the mortality can approach 10-80%. Surgical intervention within 6 hours of symptom onset increases survival rates. If the diagnosis is not made or if treatment is not started until some of the affected intestine has died, 70 to 90% of people die. A person cannot survive if almost all the small intestine dies or is removed. Even those who survive are left with a risk of re-thrombosis, short bowel, a colostomy or ileostomy 5. Many patients are left with a short gut and require long-term parenteral nutrition. The outcomes are usually worse in the elderly, those with other comorbidities, sepsis and metabolic acidosis at the time of presentation.

The prognosis for chronic mesenteric ischemia is good after a successful surgery. However, it is important to make lifestyle changes to prevent hardening of the arteries from getting worse.

People with hardening of the arteries that supply the intestines often have the same problems in blood vessels that supply the heart, brain, kidneys, or legs.

The long-term mortality among patients with venous mesenteric ischemia is heavily influenced by the underlying cause of thrombosis; the rate of 30-day survival is 80%, and the rate of 5-year survival is 70% 61.

The outcomes in patients with nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia (NOMI) depend on the management of the underlying cause; overall mortality is 50 to 83% among these patients 67.

- Clair DG, Beach JM. Mesenteric Ischemia. N Engl J Med. 2016 Mar 10;374(10):959-68. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMra1503884[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Scholtz V, Meyer F, Schulz HU, Albrecht R, Halloul Z. Gefäßchirurgische Aspekte in der Viszeralchirurgie : Ergebnisse aus einem tertiären Zentrum über einen Zeitraum von 10 Jahren [Vascular surgical aspects in abdominal surgery : Results from a tertiary care center over a 10-year time period]. Chirurg. 2019 Apr;90(4):307-317. German. doi: 10.1007/s00104-018-0726-y[↩]

- Ehlert BA. Acute Gut Ischemia. Surg Clin North Am. 2018 Oct;98(5):995-1004. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2018.06.002[↩]

- Seong EY, Zheng Y, Winkelmayer WC, Montez-Rath ME, Chang TI. The Relationship between Intradialytic Hypotension and Hospitalized Mesenteric Ischemia: A Case-Control Study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018 Oct 8;13(10):1517-1525. doi: 10.2215/CJN.13891217[↩]

- Gragossian A, Shaydakov ME, Dacquel P. Mesenteric Artery Ischemia. [Updated 2023 Aug 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513354[↩][↩]

- Patel R, Waheed A, Costanza M. Chronic Mesenteric Ischemia. [Updated 2023 Jul 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430748[↩][↩]

- Monita MM, Gonzalez L. Acute Mesenteric Ischemia. [Updated 2023 Jun 26]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431068[↩][↩]

- Prakash VS, Marin M, Faries PL. Acute and Chronic Ischemic Disorders of the Small Bowel. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2019 May 7;21(6):27. doi: 10.1007/s11894-019-0694-5[↩]

- Allain C, Besch G, Guelle N, Rinckenbach S, Salomon du Mont L. Prevalence and Impact of Malnutrition in Patients Surgically Treated for Chronic Mesenteric Ischemia. Ann Vasc Surg. 2019 Jul;58:24-31. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2019.02.009[↩]

- Ben Abdallah I, Cerceau P, Pellenc Q, Huguet A, Corcos O, Castier Y. Laparoscopic Surgery in Chronic Mesenteric Ischemia: Release of the Superior Mesenteric Artery from the Median Arcuate Ligament Using the Transperitoneal Left Retrorenal Approach. Ann Vasc Surg. 2019 Aug;59:313.e5-313.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2019.01.009[↩]

- Robles-Martín ML, Reyes-Ortega JP, Rodríguez-Morata A. A Rare Case of Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury After Mesenteric Revascularization. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2019 Jul;53(5):424-428. doi: 10.1177/1538574419839547[↩]

- Franca E, Shaydakov ME, Kosove J. Mesenteric Artery Thrombosis. [Updated 2023 May 2]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539763[↩]

- Ishii R, Sakai E, Nakajima K, Matsuhashi N, Ohata K. Non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia induced by a polyethylene glycol with ascorbate-based colonic bowel preparation. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2019 Oct;12(5):403-406. doi: 10.1007/s12328-019-00970-2[↩]

- Wyers MC. Acute mesenteric ischemia: diagnostic approach and surgical treatment. Semin Vasc Surg. 2010 Mar;23(1):9-20. doi: 10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2009.12.002[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Kärkkäinen JM, Lehtimäki TT, Manninen H, Paajanen H. Acute Mesenteric Ischemia Is a More Common Cause than Expected of Acute Abdomen in the Elderly. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015 Aug;19(8):1407-14. doi: 10.1007/s11605-015-2830-3[↩]

- Acosta S. Mesenteric ischemia. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2015 Apr;21(2):171-8. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000189[↩]

- Silva JA, White CJ. Ischemic bowel syndromes. Prim Care. 2013 Mar;40(1):153-67. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2012.11.007[↩]

- Hmoud B, Singal AK, Kamath PS. Mesenteric venous thrombosis. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2014 Sep;4(3):257-63. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2014.03.052[↩]

- Biolato M, Miele L, Gasbarrini G, Grieco A. Abdominal angina. Am J Med Sci. 2009 Nov;338(5):389-95. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181a85c3b[↩][↩]

- White CJ. Chronic mesenteric ischemia: diagnosis and management. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2011 Jul-Aug;54(1):36-40. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2011.04.005[↩]

- Hagspiel KD, Flors L, Hanley M, Norton PT. Computed tomography angiography and magnetic resonance angiography imaging of the mesenteric vasculature. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2015 Mar;18(1):2-13. doi: 10.1053/j.tvir.2014.12.002[↩]

- Oliva IB, Davarpanah AH, Rybicki FJ, Desjardins B, Flamm SD, Francois CJ, Gerhard-Herman MD, Kalva SP, Ashraf Mansour M, Mohler ER 3rd, Schenker MP, Weiss C, Dill KE. ACR Appropriateness Criteria ® imaging of mesenteric ischemia. Abdom Imaging. 2013 Aug;38(4):714-9. doi: 10.1007/s00261-012-9975-2. Erratum in: Abdom Imaging. 2014 Aug;39(4):937-9.[↩]

- Kirkpatrick ID, Kroeker MA, Greenberg HM. Biphasic CT with mesenteric CT angiography in the evaluation of acute mesenteric ischemia: initial experience. Radiology. 2003 Oct;229(1):91-8. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2291020991[↩]

- Di Minno MN, Milone F, Milone M, Iaccarino V, Venetucci P, Lupoli R, Sosa Fernandez LM, Di Minno G. Endovascular Thrombolysis in Acute Mesenteric Vein Thrombosis: a 3-year follow-up with the rate of short and long-term sequaelae in 32 patients. Thromb Res. 2010 Oct;126(4):295-8. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2009.12.015[↩][↩][↩]

- Arthurs ZM, Titus J, Bannazadeh M, Eagleton MJ, Srivastava S, Sarac TP, Clair DG. A comparison of endovascular revascularization with traditional therapy for the treatment of acute mesenteric ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2011 Mar;53(3):698-704; discussion 704-5. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.09.049[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Meilahn JE, Morris JB, Ceppa EP, Bulkley GB. Effect of prolonged selective intramesenteric arterial vasodilator therapy on intestinal viability after acute segmental mesenteric vascular occlusion. Ann Surg. 2001 Jul;234(1):107-15. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200107000-00016[↩]

- Evennett NJ, Petrov MS, Mittal A, Windsor JA. Systematic review and pooled estimates for the diagnostic accuracy of serological markers for intestinal ischemia. World J Surg. 2009 Jul;33(7):1374-83. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0074-7[↩]

- Acosta S, Nilsson T. Current status on plasma biomarkers for acute mesenteric ischemia. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2012 May;33(4):355-61. doi: 10.1007/s11239-011-0660-z[↩]

- Corcos O, Nuzzo A. Gastro-intestinal vascular emergencies. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2013 Oct;27(5):709-25. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2013.08.006[↩]

- Oldenburg WA, Lau LL, Rodenberg TJ, Edmonds HJ, Burger CD. Acute mesenteric ischemia: a clinical review. Arch Intern Med. 2004 May 24;164(10):1054-62. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.10.1054[↩]

- Boley SJ, Brandt LJ, Sammartano RJ. History of mesenteric ischemia. The evolution of a diagnosis and management. Surg Clin North Am. 1997 Apr;77(2):275-88. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70548-x[↩]

- Gatt M, Reddy BS, MacFie J. Review article: bacterial translocation in the critically ill–evidence and methods of prevention. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007 Apr 1;25(7):741-57. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03174.x[↩]

- Corcos O, Castier Y, Sibert A, Gaujoux S, Ronot M, Joly F, Paugam C, Bretagnol F, Abdel-Rehim M, Francis F, Bondjemah V, Ferron M, Zappa M, Amiot A, Stefanescu C, Leseche G, Marmuse JP, Belghiti J, Ruszniewski P, Vilgrain V, Panis Y, Mantz J, Bouhnik Y. Effects of a multimodal management strategy for acute mesenteric ischemia on survival and intestinal failure. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 Feb;11(2):158-65.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.10.027[↩]

- Jamieson WG, Pliagus G, Marchuk S, DeRose G, Moffat D, Stafford L, Finley RJ, Sibbald W, Taylor BM, Duff J. Effect of antibiotic and fluid resuscitation upon survival time in experimental intestinal ischemia. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1988 Aug;167(2):103-8.[↩]

- de Smet AM, Kluytmans JA, Cooper BS, et al. Decontamination of the digestive tract and oropharynx in ICU patients. N Engl J Med. 2009 Jan 1;360(1):20-31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800394[↩]

- Silvestri L, van Saene HK, Zandstra DF, Marshall JC, Gregori D, Gullo A. Impact of selective decontamination of the digestive tract on multiple organ dysfunction syndrome: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Crit Care Med. 2010 May;38(5):1370-6. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181d9db8c[↩]

- Kles KA, Wallig MA, Tappenden KA. Luminal nutrients exacerbate intestinal hypoxia in the hypoperfused jejunum. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2001 Sep-Oct;25(5):246-53. doi: 10.1177/0148607101025005246[↩]

- Kozar RA, Hu S, Hassoun HT, DeSoignie R, Moore FA. Specific intraluminal nutrients alter mucosal blood flow during gut ischemia/reperfusion. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2002 Jul-Aug;26(4):226-9. doi: 10.1177/0148607102026004226[↩]

- Park WM, Gloviczki P, Cherry KJ Jr, Hallett JW Jr, Bower TC, Panneton JM, Schleck C, Ilstrup D, Harmsen WS, Noel AA. Contemporary management of acute mesenteric ischemia: Factors associated with survival. J Vasc Surg. 2002 Mar;35(3):445-52. doi: 10.1067/mva.2002.120373[↩][↩][↩]

- Ryer EJ, Kalra M, Oderich GS, Duncan AA, Gloviczki P, Cha S, Bower TC. Revascularization for acute mesenteric ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2012 Jun;55(6):1682-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.12.017[↩][↩]

- Schoots IG, Levi MM, Reekers JA, Lameris JS, van Gulik TM. Thrombolytic therapy for acute superior mesenteric artery occlusion. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2005 Mar;16(3):317-29. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000141719.24321.0B[↩]

- Schermerhorn ML, Giles KA, Hamdan AD, Wyers MC, Pomposelli FB. Mesenteric revascularization: management and outcomes in the United States, 1988-2006. J Vasc Surg. 2009 Aug;50(2):341-348.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.03.004[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Beaulieu RJ, Arnaoutakis KD, Abularrage CJ, Efron DT, Schneider E, Black JH 3rd. Comparison of open and endovascular treatment of acute mesenteric ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2014 Jan;59(1):159-64. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.06.084. Epub 2013 Nov 5. Erratum in: J Vasc Surg. 2014 Jul;60(1):273.[↩]

- Björnsson S, Björck M, Block T, Resch T, Acosta S. Thrombolysis for acute occlusion of the superior mesenteric artery. J Vasc Surg. 2011 Dec;54(6):1734-42. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.07.054[↩]

- Plumereau F, Mucci S, Le Naoures P, Finel JB, Hamy A. Acute mesenteric ischemia of arterial origin: importance of early revascularization. J Visc Surg. 2015 Feb;152(1):17-22. doi: 10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2014.11.001[↩]

- Wyers MC, Powell RJ, Nolan BW, Cronenwett JL. Retrograde mesenteric stenting during laparotomy for acute occlusive mesenteric ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2007 Feb;45(2):269-75. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.10.047[↩]

- Milner R, Woo EY, Carpenter JP. Superior mesenteric artery angioplasty and stenting via a retrograde approach in a patient with bowel ischemia–a case report. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2004 Jan-Feb;38(1):89-91. doi: 10.1177/153857440403800112[↩]

- Blauw JT, Meerwaldt R, Brusse-Keizer M, Kolkman JJ, Gerrits D, Geelkerken RH; Multidisciplinary Study Group of Mesenteric Ischemia. Retrograde open mesenteric stenting for acute mesenteric ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2014 Sep;60(3):726-34. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.04.001[↩]

- Kougias P, Lau D, El Sayed HF, Zhou W, Huynh TT, Lin PH. Determinants of mortality and treatment outcome following surgical interventions for acute mesenteric ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2007 Sep;46(3):467-74. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.04.045[↩][↩][↩]

- Acosta-Merida MA, Marchena-Gomez J, Hemmersbach-Miller M, Roque-Castellano C, Hernandez-Romero JM. Identification of risk factors for perioperative mortality in acute mesenteric ischemia. World J Surg. 2006 Aug;30(8):1579-85. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0560-5[↩]

- Oderich GS, Bower TC, Sullivan TM, Bjarnason H, Cha S, Gloviczki P. Open versus endovascular revascularization for chronic mesenteric ischemia: risk-stratified outcomes. J Vasc Surg. 2009 Jun;49(6):1472-9.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.02.006[↩][↩]

- Oderich GS, Malgor RD, Ricotta JJ 2nd. Open and endovascular revascularization for chronic mesenteric ischemia: tabular review of the literature. Ann Vasc Surg. 2009 Sep-Oct;23(5):700-12. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2009.03.002. Epub 2009 Jun 21. Erratum in: Ann Vasc Surg. 2010 Jan;24(1):151. Sullivan, Timothy M [removed].[↩][↩]

- Cai W, Li X, Shu C, Qiu J, Fang K, Li M, Chen Y, Liu D. Comparison of clinical outcomes of endovascular versus open revascularization for chronic mesenteric ischemia: a meta-analysis. Ann Vasc Surg. 2015 Jul;29(5):934-40. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2015.01.010[↩]

- Atkins MD, Kwolek CJ, LaMuraglia GM, Brewster DC, Chung TK, Cambria RP. Surgical revascularization versus endovascular therapy for chronic mesenteric ischemia: a comparative experience. J Vasc Surg. 2007 Jun;45(6):1162-71. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.01.067[↩][↩]

- Tallarita T, Oderich GS, Macedo TA, Gloviczki P, Misra S, Duncan AA, Kalra M, Bower TC. Reinterventions for stent restenosis in patients treated for atherosclerotic mesenteric artery disease. J Vasc Surg. 2011 Nov;54(5):1422-1429.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.06.002[↩]

- van Petersen AS, Kolkman JJ, Beuk RJ, Huisman AB, Doelman CJ, Geelkerken RH; Multidisciplinary Study Group Of Splanchnic Ischemia. Open or percutaneous revascularization for chronic splanchnic syndrome. J Vasc Surg. 2010 May;51(5):1309-16. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.12.064[↩]

- Cho JS, Carr JA, Jacobsen G, Shepard AD, Nypaver TJ, Reddy DJ. Long-term outcome after mesenteric artery reconstruction: a 37-year experience. J Vasc Surg. 2002 Mar;35(3):453-60. doi: 10.1067/mva.2002.118593[↩]

- Jimenez JG, Huber TS, Ozaki CK, Flynn TC, Berceli SA, Lee WA, Seeger JM. Durability of antegrade synthetic aortomesenteric bypass for chronic mesenteric ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2002 Jun;35(6):1078-84. doi: 10.1067/mva.2002.124377. Erratum in: J Vasc Surg 2002 Sep;36(3):548. Jimenez Javier G [corrected to Jimenez Jesus G].[↩]

- Kruger AJ, Walker PJ, Foster WJ, Jenkins JS, Boyne NS, Jenkins J. Open surgery for atherosclerotic chronic mesenteric ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2007 Nov;46(5):941-5. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.06.036[↩]

- Rhee RY, Gloviczki P, Mendonca CT, Petterson TM, Serry RD, Sarr MG, Johnson CM, Bower TC, Hallett JW Jr, Cherry KJ Jr. Mesenteric venous thrombosis: still a lethal disease in the 1990s. J Vasc Surg. 1994 Nov;20(5):688-97. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(94)70155-5[↩]

- Acosta S, Alhadad A, Svensson P, Ekberg O. Epidemiology, risk and prognostic factors in mesenteric venous thrombosis. Br J Surg. 2008 Oct;95(10):1245-51. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6319[↩][↩]

- Takahashi N, Kuroki K, Yanaga K. Percutaneous transhepatic mechanical thrombectomy for acute mesenteric venous thrombosis. J Endovasc Ther. 2005 Aug;12(4):508-11. doi: 10.1583/04-1335MR.1[↩]

- Ozdogan M, Gurer A, Gokakin AK, Kulacoglu H, Aydin R. Thrombolysis via an operatively placed mesenteric catheter for portal and superior mesenteric vein thrombosis: report of a case. Surg Today. 2006;36(9):846-8. doi: 10.1007/s00595-006-3243-4[↩]

- Boley SJ, Sprayregan S, Siegelman SS, Veith FJ. Initial results from an agressive roentgenological and surgical approach to acute mesenteric ischemia. Surgery. 1977 Dec;82(6):848-55.[↩]

- Luther B, Mamopoulos A, Lehmann C, Klar E. The Ongoing Challenge of Acute Mesenteric Ischemia. Visc Med. 2018 Jul;34(3):217-223. doi: 10.1159/000490318[↩]

- Mohapatra A, Salem KM, Jaman E, Robinson D, Avgerinos ED, Makaroun MS, Eslami MH. Risk factors for perioperative mortality after revascularization for acute aortic occlusion. J Vasc Surg. 2018 Dec;68(6):1789-1795. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2018.04.037[↩]

- Schoots IG, Koffeman GI, Legemate DA, Levi M, van Gulik TM. Systematic review of survival after acute mesenteric ischaemia according to disease aetiology. Br J Surg. 2004 Jan;91(1):17-27. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4459[↩]