Sclerosing mesenteritis

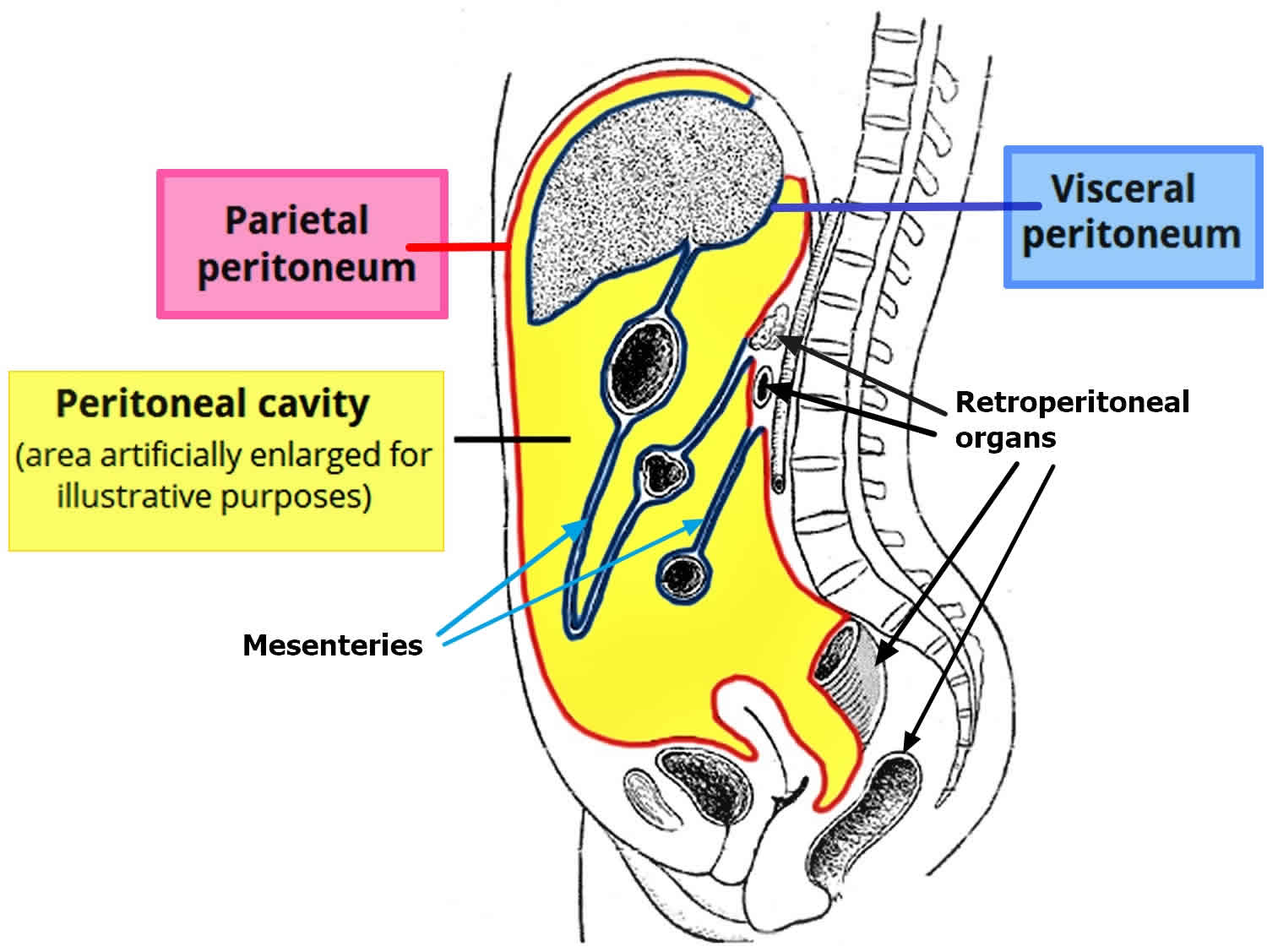

Sclerosing mesenteritis is a rare condition causing inflammation, fat necrosis, scarring (fibrosis) of the mesentery, a fold of membrane (a fan-shaped fold of the peritoneum [two layers of peritoneum fused to form a mesentery]) that attaches the jejunum and the ileum of your small intestine to the back wall of your abdomen and holds it in place 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15. Various terms have been used for sclerosing mesenteritis including “misty mesentery”, mesenteric lipodystrophy, mesenteric panniculitis, Weber-Christian disease, liposclerotic mesenteritis, retractile mesenteritis, mesenteric fibrosis, xanthogranulomatous mesenteritis, idiopathic mesenteric fibrosis, inflammatory pseudotumor, and systemic nodular panniculitis 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 1. These terms likely represent a continuum of the same disease with differing ratios of scarring (fibrosis), fat necrosis, and inflammation, and thus the unifying term of “sclerosing mesenteritis” has been proposed 20. Sclerosing mesenteritis is a chronic inflammatory condition that affects your mesentery, a double layer of folded peritoneum with a layer of fatty tissue in between that attaches parts of your small intestines to the back wall of your abdomen. “Mesenteritis” means inflammation of the mesentery and the fat layer (adipose tissue), and “sclerosing” means scarring. Sclerosing mesenteritis causes chronic inflammation of the mesentery. Over time, chronic inflammation causes scarring or “fibrosis” of the tissues, making them harden, usually in one or several spots, which can look like masses on radiology images. You may have symptoms of abdominal pain and swelling. You may be diagnosed with sclerosing mesenteritis while you are receiving care for another condition. Up to 60% of patients with sclerosing mesenteritis findings on CT are asymptomatic, but this is likely an underestimate, given that asymptomatic persons do not all undergo imaging 22. Among those with symptoms, abdominal pain is most common (up to 75%), with bloating (10% to 25%), diarrhea or constipation (10% to 25%), nausea and vomiting (5% to 15%), and weight loss (20%) 23. A palpable abdominal mass is often not found.

The cause of sclerosing mesenteritis is unclear (idiopathic), but it may be associated with trauma, autoimmune diseases, or cancer. People with sclerosing mesenteritis do not have a higher prevalence of autoimmunity, but may have increased rates of metabolic syndrome, obesity, coronary artery disease, and urinary tract stones (urolithiasis) 24.

An older autopsy study of sclerosing mesenteritis suggests that the prevalence of this condition is 1.26% based on histopathologic features 25. However, a multitude of newer studies focusing on CT diagnosis of sclerosing mesenteritis have been conducted, suggesting that the overall prevalence may be greater with a range of 0.18% to 3.14% of the population 26, 27, 28, 29. The variability in the reported prevalence appears to be partially due to the radiographic criteria used for diagnosis. The largest of these studies analyzed the abdominal CT of 65,278 patients and discovered the prevalence of sclerosing mesenteritis, specifically mesenteric panniculitis, to be 1.1% 29. While the number of reported sclerosing mesenteritis cases has notably increased since 1980, it is unclear whether this is confounded by greater awareness of the condition and/or improved as well as more frequent imaging 3, 27.

Sclerosing mesenteritis is most commonly diagnosed in the fifth or sixth decade of life, as exemplified in a systematic review of 192 cases, where people with a history of abdominal surgery and/or autoimmune disease may be at higher risk 30, 31, 29. The prevalence of sclerosing mesenteritis in male and female patients is variable; some studies report a male predominance, whereas others report a female majority 30, 31, 29, 27. Although most investigations of sclerosing mesenteritis were conducted on White individuals, a systematic review of 192 cases suggests that sclerosing mesenteritis is most common in White individual and least common in Hispanics 31.

Sclerosing mesenteritis has been associated with other medical conditions including 32, 27, 33, 34:

- Cancer

- Lymphoma (up to 10% risk of developing lymphoma)

- Lung cancer

- Melanoma

- Colon cancer

- Kidney cancer

- Myeloma

- Stomach carcinoma

- Recent abdominal surgery

- Systemic inflammatory conditions

- Retroperitoneal fibrosis

- sclerosing cholangitis

- Riedel thyroiditis

- Orbital pseudotumor

- Autoimmune conditions (may be related to IgG4-related disease)

- May be related to Weber-Christian disease, a rare, recurrent inflammatory condition that causes painful, tender lumps in the fatty tissue just beneath the skin, known as panniculitis. These nodules are often accompanied by systemic symptoms like fever, malaise, and joint pain, and they heal by leaving behind depressed, atrophic scars. While typically affecting the subcutaneous fat, it can also involve visceral fat, making it potentially serious

Some patients with sclerosing mesenteritis are asymptomatic and others can present with various nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms 30, 31.

Across numerous studies, the most common symptom is abdominal pain, affecting 70% or more of the cases 30, 31. Other common symptoms based on larger studies include weight loss (∼23%), diarrhea (19.3% to 25%), nausea or vomiting (18.2% to 21%), anorexia or loss of appetite (13.5% to 16%), abdominal bloating or distention (9.4% to 26%), and constipation (10.9% to 15%) 30, 31.

With respect to physical examination, the most common finding is abdominal tenderness (24% to 38%); other typical features are a palpable abdominal mass (15% to 34.4%), abdominal distention (14% to 15.1%), and fever (6% to 26%) 30, 31.

Conversely, a significant proportion of sclerosing mesenteritis cases are discovered incidentally on imaging or during abdominal surgery in asymptomatic patients or in patients with symptoms attributed to another condition 2. Whereas Sharma et al 31 found that 1.6% of sclerosing mesenteritis cases in their series were incidentally discovered. A large retrospective study of 92 patients with sclerosing mesenteritis reported sclerosing mesenteritis to be an incidental finding in 10% of their cohort with no symptoms attributable to mesenteric disease 30. The number of sclerosing mesenteritis cases diagnosed incidentally is likely to rise, given improved quality and frequency of imaging.

Sclerosing mesenteritis features suggesting a more severe clinical course include 20, 31, 35, 36:

- Omental, retroperitoneal, pelvic fat, or colonic mesentery involvement;

- Associated bowel obstruction or ischemia, venous thrombosis or thromboembolism, sepsis, protein losing enteropathy, or kidney failure;

- Marked C-reactive protein (CRP) or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) elevations;

- Coexisting autoimmune disease;

- Arterial narrowing; and/or ascites.

Tests and procedures used to diagnose sclerosing mesenteritis include:

- Physical exam. During a physical exam, a member of your healthcare team looks for clues that may help find a diagnosis. For instance, sclerosing mesenteritis often forms a mass in the upper abdomen that can be felt during a physical exam.

- Imaging tests. Imaging tests of the abdomen may show sclerosing mesenteritis. Imaging tests may include computerized tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

- Biopsy (removing a sample of tissue for testing). If you’re experiencing sclerosing mesenteritis symptoms, a biopsy may be needed to rule out other diseases and to make a definitive diagnosis. A biopsy sample may be collected during surgery or by inserting a long needle through the skin. Before starting treatment, a biopsy can confirm the diagnosis and rule out other possibilities, including certain cancers such as lymphoma and carcinoid.

As sclerosing mesenteritis has a strong inflammatory component, inflammatory markers including erythrocyte sedimentation rate (14% to 88.4%) and C-reactive protein (86.5%) are often elevated 30, 31. In addition, serum IgG4 may be high in sclerosing mesenteritis, but this is less commonly reported 37.

Sclerosing mesenteritis was historically diagnosed by imaging with confirmatory histopathologic evaluation, but now practice has shifted away from histopathologic evaluation to limit invasive unnecessary biopsies unless there is strong clinical suspicion of malignant disease affecting the mesentery31. The most commonly accepted diagnostic modality is currently CT of the abdomen with contrast enhancement using certain radiographic criteria to make the diagnosis of sclerosing mesenteritis. While the literature varies in these radiographic criteria, the Coulier classification is often utilized 38, 27.

Coulier CT diagnostic criteria for sclerosing mesenteritis 38, 27:

- A hazy mesenteric fat mass displacing intestine;

- Higher attenuation in the mesenteric fat mass than adjacent mesentery, but no enhancement with intravenous contrast;

- The presence of lymph nodes <1 cm;

- A hypoattenuated halo sign around central vessels; and

- A thin surrounding fibrotic pseudocapsule.

CT images with these diagnostic features are shown in Figure 6 below.

Briefly, the diagnosis of sclerosing mesenteritis can be made if 3 or more signs are observed: 1) A well-defined mesenteric fatty mass lesion causing mass effect on neighboring structures; 2) Composed of mesenteric fatty tissue with higher attenuation than adjacent adipose tissue; 3) Small soft tissue lymph nodes in the mesenteric fat; 4) Halo sign (lymph nodes or mesenteric vessels surrounded by a hypoattenuated fatty ring); and 5) Mesenteric fat surrounded by a hyperattenuating pseudocapsule.

Currently, there are no official guidelines for the management of sclerosing mesenteritis, and recommendations are largely based on expert opinion. Asymptomatic patients can be observed without treatment as the risks may outweigh the benefits in this population 30. Medical management should be offered to symptomatic patients with the goal of the treatment being symptom resolution rather than changes on imaging, which may remain stable despite symptom improvement 30, 8, 39. Given this, in the absence of considerable clinical decline, the literature recommends against serial CT scans on follow-up 30, 8. Based on expert opinion, in patients presenting solely with abdominal pain, neuromodulators can be considered primary treatment. For those with more severe symptoms or complications of sclerosing mesenteritis, the first-line medication for sclerosing mesenteritis is a combination of tamoxifen 10 mg twice daily and prednisone 40 mg daily that is tapered during 3 months, with the tamoxifen being continued indefinitely 30. This is based on a large retrospective study of 92 patients with sclerosing mesenteritis in which the median follow-up was 20.5 months in patients who received treatment 30. In this investigation, of the 32/92 cases that received any drug management, the combination of tamoxifen and prednisone taper at varying doses was used in 20 cases. Sixty percent of these patients had symptom improvement within 12 to 16 weeks, and only 10% had symptom progression 30. For the remaining patients, only 1 improved after receiving a regimen that did not include tamoxifen 30. However, this combination of tamoxifen and prednisone has not been studied in randomized controlled trials.

In the setting in which tamoxifen is contraindicated, such as in a patient with a condition where a blood clot forms in a vein (venous thromboembolism), the adverse effects are intolerable, or the patient is not responsive to treatment, other agents including azathioprine, colchicine, and thalidomide can be trialed. However, evidence for these agents in sclerosing mesenteritis is scarce and mainly based on case reports, small series, or pilot studies, all of which lack a control group 30, 39.

Surgery is reserved for patients with persistent mechanical bowel obstruction that is refractory to medical management 30. Akram et al 30 reported that of the 12 patients who underwent surgical management alone, only 2 had symptom improvement. In addition, surgery is not always feasible, depending on the location of inflammation and degree of vascular involvement. Medical management can be trialed if sclerosing mesenteritis is refractory to surgical management.

Disease-related complications develop in approximately 21% to 24% of patients with sclerosing mesenteritis. Based on 2 of the largest studies on this topic, the most common are small bowel obstruction, ileus, or ischemia (24%); chylous ascites (14%); and mesenteric vessel thrombosis (3%) 30, 31. Other complications associated with sclerosing mesenteritis are treatment related 30, 31. For example, in a large retrospective study of 92 cases, the adverse effects of tamoxifen ranged from mild to severe, with patients experiencing hot flashes and vaginal dryness (57%) to venous thromboembolism (16%) 30. Although rare, possible treatment-associated fatalities have been reported 30.

Figure 1. Mesentery

Figure 2. Mesentery anatomy

Footnotes: Anterior and sagittal sections of the abdominal cavity. The mesentery is a double fold of the peritoneum. There are true and specialized mesenteries. The true mesenteries connect to the posterior peritoneal wall. These are small bowel mesentery, transverse mesocolon and sigmoid mesentery (or mesosigmoid). The specialized mesenteries do not connect to the posterior peritoneal wall. These are greater omentum, lesser omentum and mesoappendix. The omentum is divided into the greater and lesser omentum. The greater omentum is subdivided into: gastrocolic ligament, gastrosplenic ligament and gastrophrenic ligament. The lesser omentum is subdivided into gastrohepatic ligament and hepatoduodenal ligament.

Figure 4. Sclerosing mesenteritis CT scan (“misty mesentery” sign)

Footnotes: 55 years woman with abdominal pain and tenderness on physical exam. CT features are well-demarcated or ill-defined mesenteric mass-like lesion with surrounding “misty” attenuation or “misty” soft-tissue attenuation. Smudging of the fat planes surrounding the superior mesenteric vessels and their branches within the root of the small bowel mesentery, accompanied by multiple prominent mesenteric lymph nodes, is compatible with the “misty mesentery sign”. In addition, a 25-mm unilocular mesenteric cyst is seen in the right lower quadrant. The hepatic attenuation value is less than the spleen’s, suggesting a fatty liver. Degenerative changes, such as osteophytosis, are seen in the lumbar spine. The L5 vertebra is sacralized. Grade I spondylolisthesis of L4 on L5 is present with bilateral spondylolysis.

[Source 40 ]Figure 5. Sclerosing mesenteritis diagnostic algorithm

Footnote: Algorithm for the evaluation and treatment of patients with sclerosing mesenteritis.

Abbreviation: MRI = magnetic resonance imaging.

[Source 1 ]A frequent concern of patients regarding sclerosing mesenteritis is whether the imaging findings are warning signs of an increased risk of intra-abdominal cancer. Although some have suggested that sclerosing mesenteritis may be a paraneoplastic syndrome (a set of signs and symptoms that can occur when you have cancer, where the malignant tumors release substances that cause your body’s organs and body systems to behave abnormally or your body’s attempt to destroy a tumor can cause unintended damage to healthy tissue; the damage can cause symptoms of a paraneoplastic syndrome) 22, 41. However, current evidence does not support this assumption that sclerosing mesenteritis may be a paraneoplastic syndrome 42, 28, 31, 43. Moreover, there does seem to be an overlap with sclerosing mesenteritis findings and certain types of cancer, including lymphoma, gynecologic cancers, and carcinoid tumors 44, 45.

The presence of a mesenteric mass or intra-abdominal lymph node >10 mm in size should raise suspicion for an underlying cancer 44, 46. In 1 prospective study of more than 400 patients with sclerosing mesenteritis, the rate of subsequent cancer was 1%; all were B-cell lymphomas, and had either a soft tissue nodule >10 mm or abdominopelvic enlarged lymph node 44. Use of positron-emission tomography (PET) has been investigated in these cases, with favorable diagnostic performance 45, 47.

In addition, sclerosing mesenteritis (often asymptomatic) has also been reported following cancer therapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors 48.

Published recommendations for follow-up imaging because of concerns about associated cancer vary widely, from no repeat imaging, to annual repeating examinations up to 5 years 44, 46, 41, 49. In a meta-analysis of 4 case-control studies, an increased risk of cancer was not detectable 42, but another study reported a small long-term increased risk of lymphoma in those without initial features of malignancy, with 80% detectable in the first year 44. The second reason for repeat imaging is to assess progression of inflammation. Although the data are limited, except in the most severe cases, most patients—requiring treatment or not—achieve stable disease without radiologic progression after 2 years 50. During follow-up imaging, if any sclerosing mesenteritis features concerning for cancer occur, including significant growth in the mesenteric mass or new enlarged lymph node (lymphadenopathy), biopsy should be performed 45. For asymptomatic cases without initial features concerning for associated cancer, the American Gastroenterological Association suggest that patients be followed with annual CT scans for 2 years to ensure stability, and thereafter performed for concerning symptoms 1.

Is sclerosing mesenteritis a cancer?

Sclerosing mesenteritis is not a cancer in itself, although sclerosing mesenteritis is often associated with cancer. Cancer is one possible cause of chronic inflammation. Infectious diseases and autoimmune disease are another possible causes. Research suggests that people who’ve experienced inflammation from one of these causes are more likely to develop sclerosing mesenteritis. It’s as if their mesentery “catches” the inflammation and continues to keep it alive.

Scar tissue doesn’t multiply the way that cancer does, but it can appear to “spread,” and it can look like cancer on radiologic studies. Sclerosing mesenteritis is often characterized by a solid, focal “mass” of scar tissue in your mesentery, resembling a tumor. The two conditions can also present with similar symptoms. It can take some time and testing for your doctor to definitively tell them apart.

Is sclerosing mesenteritis the same thing as mesenteric panniculitis?

Most doctors use the term sclerosing mesenteritis and mesenteric panniculitis interchangeably 30, 8, 31, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 1. These terms likely represent a continuum of the same disease with differing ratios of scarring (fibrosis), fat necrosis, and inflammation, and thus the unifying term of “sclerosing mesenteritis” has been proposed 20. They’re both described as “idiopathic” inflammation of the mesentery, which means that the inflammation appears to occur spontaneously. These terms likely represent a continuum of the same disease with differing ratios of scarring (fibrosis), fat necrosis, and inflammation, and thus the unifying term of “sclerosing mesenteritis” has been proposed 20. However, some have suggested that “sclerosing mesenteritis” should be used to describe a more advanced stage of the disease, or a more severe form, when it lasts longer or the symptoms are worse.

“Mesenteric panniculitis” literally means inflammation of the fat tissue of the mesentery. Since the name doesn’t reference sclerosis, some argue that mesenteric panniculitis should be used to describe an earlier stage of inflammation, before scarring takes place. They argue that when sclerosis sets in, it means the disease has progressed a long way and may be more complicated or more difficult to treat.

Is sclerosing mesenteritis a chronic condition?

By definition, sclerosing mesenteritis is a chronic condition and a progressive one. Because it takes consistent inflammation over a long period of time to cause scarring (fibrosis). It happens in stages: first, the fat begins to break down, then different types of cells begin to infiltrate the tissue, and finally, scar tissue develops. But that being said, sclerosing mesenteritis doesn’t always continue to progress, and it often goes away on its own.

Sclerosing mesenteritis causes

The cause of sclerosing mesenteritis is not known. Risk factors for and comorbidities associated with sclerosing mesenteritis, predominantly based on case series and retrospective studies, include history of abdominal surgery, history of abdominal trauma, concurrent intra-abdominal disease, chronic infection or ischemia, medications, and autoimmune conditions 30, 31. Two of the largest studies on sclerosing mesenteritis reported that 28.6% to 35% of patients have a history of abdominal surgery or trauma; the most common were cholecystectomy (a surgical procedure to remove the gallbladder), appendectomy (a surgical procedure to remove the appendix), and cesarean section or hysterectomy (a surgical procedure to remove the uterus or womb) 30, 31. Other frequent associations were intra-abdominal disease or malignant neoplasia (8.9% to 18%) and autoimmune disease (5.7% to 10%); the most common autoimmune diseases included retroperitoneal fibrosis, Sjögren syndrome, ankylosing spondylitis, rheumatoid arthritis, and sarcoidosis 30, 31. Other autoimmune diseases associated with sclerosing mesenteritis include primary sclerosing cholangitis, Riedel thyroiditis, systemic lupus erythematous, and IgG4 disease 30, 37, 51, 52.

While IgG4 disease has been implicated in sclerosing mesenteritis given cases with elevations in serum IgG4, cases with no such elevation but IgG4-positive plasma cell infiltration on histopathologic evaluation have been reported 30, 37.

Lastly, the role of autoimmunity as a risk factor for sclerosing mesenteritis is also supported by treatment regimens involving corticosteroids or immunosuppressants that result in symptom improvement 30, 31. Association with chronic infections such as HIV, Mycobacterium, Schistosomiasis, and Cryptococcus, and medications,including pergolide and paroxetine, is scarce in the literature and largely based on case reports 31, 53, 54, 55.

There has been much debate in the literature on cancerous tumor as a risk factor for sclerosing mesenteritis or sclerosing mesenteritis being a paraneoplastic condition 30, 31, 27. For example, a retrospective study by Daskalogiannaki et al 27 reported that 69.4% of patients with sclerosing mesenteritis had coexisting malignant disease, such as non-Hodgkin lymphoma, lung cancer, colorectal cancer, and genitourinary malignant neoplasms. Many of these studies that suggest an association between cancer and sclerosing mesenteritis or indicate sclerosing mesenteritis as a paraneoplastic syndrome are case series or retrospective studies. Conversely, a systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies reported that sclerosing mesenteritis does not confer an increased risk for cancers 42. That study of 415 patients with sclerosing mesenteritis and 1132 matched controls also found that patients with sclerosing mesenteritis were not at increased risk for specific types of malignant disease 42. Taken together, this suggests that the proposed relationship between malignant disease and sclerosing mesenteritis was primarily based on lower quality data 2.

Sclerosing mesenteritis signs and symptoms

Some patients with sclerosing mesenteritis are asymptomatic and others can present with various nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms 30, 31. Many people with sclerosing mesenteritis have no symptoms at all and are unaware they have the condition. The most common symptoms people report are abdominal pain and bloating. Severe inflammation may trigger diarrhea or fever. You may be able to feel a palpable mass when you touch your abdomen. In rare cases, a mass may obstruct your small intestine, causing additional symptoms of nausea, vomiting and weight loss.

Across numerous studies, the most common symptom is abdominal pain, affecting 70% or more of the cases 30, 31. Other common symptoms based on larger studies include weight loss (∼23%), diarrhea (19.3% to 25%), nausea or vomiting (18.2% to 21%), anorexia or loss of appetite (13.5% to 16%), abdominal bloating or distention (9.4% to 26%), and constipation (10.9% to 15%) 30, 31.

With respect to physical examination, the most common finding is abdominal tenderness (24% to 38%); other typical features are a palpable abdominal mass (15% to 34.4%), abdominal distention (14% to 15.1%), and fever (6% to 26%) 30, 31.

Conversely, a significant proportion of sclerosing mesenteritis cases are discovered incidentally on imaging or during abdominal surgery in asymptomatic patients or in patients with symptoms attributed to another condition 2. Whereas Sharma et al 31 found that 1.6% of sclerosing mesenteritis cases in their series were incidentally discovered. A large retrospective study of 92 patients with sclerosing mesenteritis reported sclerosing mesenteritis to be an incidental finding in 10% of their cohort with no symptoms attributable to mesenteric disease 30. The number of sclerosing mesenteritis cases diagnosed incidentally is likely to rise, given improved quality and frequency of imaging.

Severe disease

Sclerosing mesenteritis features suggesting a more severe clinical course include 20, 31, 35, 36:

- Omental, retroperitoneal, pelvic fat, or colonic mesentery involvement;

- Associated bowel obstruction or ischemia, venous thrombosis or thromboembolism, sepsis, protein losing enteropathy, or kidney failure;

- Marked C-reactive protein (CRP) or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) elevations;

- Coexisting autoimmune disease;

- Arterial narrowing; and/or ascites.

Sclerosing mesenteritis diagnosis

Tests and procedures used to diagnose sclerosing mesenteritis include:

- Physical exam. During a physical exam, a member of your healthcare team looks for clues that may help find a diagnosis. For instance, sclerosing mesenteritis often forms a mass in the upper abdomen that can be felt during a physical exam.

- Imaging tests. Imaging tests of the abdomen may show sclerosing mesenteritis. Imaging tests may include computerized tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

- Biopsy (removing a sample of tissue for testing). If you’re experiencing sclerosing mesenteritis symptoms, a biopsy may be needed to rule out other diseases and to make a definitive diagnosis. A biopsy sample may be collected during surgery or by inserting a long needle through the skin. Before starting treatment, a biopsy can confirm the diagnosis and rule out other possibilities, including certain cancers such as lymphoma and carcinoid.

As sclerosing mesenteritis has a strong inflammatory component, inflammatory markers including erythrocyte sedimentation rate (14% to 88.4%) and C-reactive protein (86.5%) are often elevated 30, 31. In addition, serum IgG4 may be high in sclerosing mesenteritis, but this is less commonly reported 37.

Sclerosing mesenteritis was historically diagnosed by imaging with confirmatory histopathologic evaluation, but now practice has shifted away from histopathologic evaluation to limit invasive unnecessary biopsies unless there is strong clinical suspicion of malignant disease affecting the mesentery31. The most commonly accepted diagnostic modality is currently CT of the abdomen with contrast enhancement using certain radiographic criteria to make the diagnosis of sclerosing mesenteritis. While the literature varies in these radiographic criteria, the Coulier classification is often utilized 38, 27.

Coulier CT diagnostic criteria for sclerosing mesenteritis 38, 27:

- A hazy mesenteric fat mass displacing intestine;

- Higher attenuation in the mesenteric fat mass than adjacent mesentery, but no enhancement with intravenous contrast;

- The presence of lymph nodes <1 cm;

- A hypoattenuated halo sign around central vessels; and

- A thin surrounding fibrotic pseudocapsule.

CT images with these diagnostic features are shown in Figure 5 below.

Briefly, the diagnosis of sclerosing mesenteritis can be made if 3 or more signs are observed: 1) A well-defined mesenteric fatty mass lesion causing mass effect on neighboring structures; 2) Composed of mesenteric fatty tissue with higher attenuation than adjacent adipose tissue; 3) Small soft tissue lymph nodes in the mesenteric fat; 4) Halo sign (lymph nodes or mesenteric vessels surrounded by a hypoattenuated fatty ring); and 5) Mesenteric fat surrounded by a hyperattenuating pseudocapsule.

However, the Coulier classification has not been validated. Although abdominal ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging can also detect sclerosing mesenteritis, CT of the abdomen is the preferred imaging modality, given that it has been the most extensively studied 56, 57. Similarly, positron emission tomography (PET) or CT is less frequently used but may have a role in differentiating sclerosing mesenteritis from malignant involvement of the mesentery in oncologic patients, including lymphoma 58.

Taken together, sclerosing mesenteritis should be considered in patients in the fifth or sixth decade of life, with a history of abdominal surgery or autoimmune disease, presenting with abdominal pain, weight loss, diarrhea, and an abdominal mass on examination with various other nonspecific gastrointestinal signs and symptoms. Given this overall nonspecific presentation, on evaluation of patients for sclerosing mesenteritis, the differential diagnoses are broad but important conditions to consider include mesenteric edema/hemorrhage and infiltration of the mesentery by inflammatory cells or tumor as they can mimic increased mesenteric fat density on CT 59.

Mesenteric edema can be seen with hypoalbuminemia or ascites due to conditions such as cirrhosis, portal hypertension, congestive heart failure, and kidney disease 59. The patient’s history is vital in excluding this condition. Similarly, the history is important to rule out mesenteric hemorrhage, which can be seen with abdominal trauma, anticoagulation use, and iatrogenic instrumentation. Whereas pancreatitis is the most common, many inflammatory conditions affecting the gastrointestinal tract, such as inflammatory bowel disease, cholecystitis, appendicitis, diverticulitis, and infections like tuberculosis peritonitis, can cause inflammation of the nearby mesentery 59. Patient history, clinical features, and appropriate work-up, such as peritoneal fluid analysis in cases of ascites, are vital in excluding these other conditions.

Most important but perhaps most challenging is to rule out mesenteric tumor. The solid tumor most frequently affecting the mesentery is lymphoma 59, 60. Early-stage lymphoma is difficult to distinguish from sclerosing mesenteritis on imaging, given that lymph nodes may be slightly enlarged and the halo sign can be present in both 61. Flow cytometry may be helpful in diagnosis of lymphoma. In addition, positron emission tomography (PET) or CT may be of utility in differentiating between sclerosing mesenteritis and mesenteric involvement of lymphoma as the enlarged lymph nodes would not be hypermetabolic in sclerosing mesenteritis 58. However, if there is high clinical suspicion of lymphoma or other malignant involvement of the mesentery or findings on work-up are equivocal, a biopsy should be done for definitive diagnosis.

Other common neoplastic mimics of sclerosing mesenteritis include metastatic carcinoid tumors, desmoid tumors (mesenteric fibromatosis), and mesenteric carcinomatosis (secondary metastases to the mesentery) 60. Metastatic carcinoid tumors are often difficult to distinguish from the fibrotic stage of sclerosing mesenteritis, given the desmoplastic reaction that can be seen with carcinoid tumors 60. However, sclerosing mesenteritis most commonly affects the root of the small bowel mesentery, whereas metastatic carcinoid tumors more commonly are located at the right lower quadrant or ileum 60. Evidence of the primary carcinoid lesion, liver metastases, or carcinoid syndrome and nuclear medicine studies with octreotide are also helpful in distinguishing the two conditions 60. Mesenteric desmoid tumors can be seen in genetic disorders such as familial adenomatous polyposis, and therefore family history may help distinguish this from sclerosing mesenteritis 60. Lastly, mesenteric carcinomatosis may arise from various primary sources, such as breast, lung, genitourinary, gastrointestinal, and melanoma.8 Supplementing the medical history, the presence of multiple lesions or metastatic disease elsewhere is more suggestive of mesenteric carcinomatosis 60.

Imaging tests

CT diagnostic criteria for sclerosing mesenteritis were established by Coulier are 38, 27:

- A hazy mesenteric fat mass displacing intestine;

- Higher attenuation in the mesenteric fat mass than adjacent mesentery, but no enhancement with intravenous contrast;

- The presence of lymph nodes <1 cm;

- A hypoattenuated halo sign around central vessels; and

- A thin surrounding fibrotic pseudocapsule.

CT images with these diagnostic features are shown in Figure 5 below.

The presence of 3 or more of these CT features is suggestive of sclerosing mesenteritis 1. A hazy mesentery without nodes, halo sign, or pseudocapsule is therefore not diagnostic for sclerosing mesenteritis and, without other symptoms, typically does not require follow-up 1. Although definitive diagnosis requires biopsy, in patients with characteristic findings on imaging and no alarm features (fever, night sweats, unintentional weight loss), the risk of cancer is very low and a presumptive diagnosis can be made without a biopsy in most cases 24. Calcifications and retraction of the surrounding bowel, characteristic of more severe disease and possible cancer (Figure B and C), typically warrants biopsy, unless an association with IgG4 disease can be established.

Figure 6. Sclerosing mesenteritis CT

Footnotes: CT images of patients with sclerosing mesenteritis. (A) CT with classic diagnostic findings including central vessels with halos (asterisks) and surrounding pseudocapsule (arrows). (B) Calcified mesenteric mass with bowel retraction. (C) “Misty mesentery” in a patient with sclerosing mesenteritis. (D) Calcified mesenteric mass with retraction and bowel thickening.

[Source 1 ]Laboratory findings

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) may be elevated, but not in all cases. There is scant literature on these biomarkers and their role in management or follow-up is uncertain at this time.

IgG4

Rarely, patients with sclerosing mesenteritis have IgG4-related disease, which often has an atypical presentation 22, 41. On CT, the inflammation can appear unlike sclerosing mesenteritis, with malignant features (indistinct margins, apparent invasion of adjacent organs, multiple enlarged lymph nodes). Only half have elevated serum IgG4 levels to suggest the diagnosis 37. A surgical biopsy with IgG4 staining may be required if the IgG4 level is normal and the imaging is not diagnostic for sclerosing mesenteritis 1.

Biopsy

If the imaging study is classic for sclerosing mesenteritis (Figure 5) and there are no concerns for cancer, then biopsy is unnecessary before initiating treatment 1.

Biopsy should be considered if there are sclerosing mesenteritis features that look like cancer, including 44, 46, 47:

- Associated lymph nodes >1 cm;

- Lymph nodes with SUVmax ≥3.0 on 18FDG PET/CT;

- Lymphadenopathy in another intra-abdominal location; and/or

- Spiculated, necrotic, calcified, or invasive appearance, including absence of central halo sign.

In patients with features that look like cancer, 18FDG-PET/CT is helpful for characterization and to identify all potentially accessible nodes for biopsy. IgG4-related sclerosing mesenteritis disease can appear invasive and have accompanying lymphadenopathy. Biopsy is generally required to make this diagnosis and to exclude cancer.

Sclerosing mesenteritis differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for sclerosing mesenteritis includes other mesenteric conditions, usually distinctly different on imaging.

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) can present with mesenteric infiltration or a mass lesion that is difficult to distinguish from sclerosing mesenteritis on imaging alone. It also can cause enlargement of lymph nodes in the mesentery, with or without enlarged nonmesenteric lymph nodes or splenomegaly 44.

- Peritoneal carcinomatosis is usually associated with abnormal buildup of fluid in the abdomen (ascites) and multiple enhancing mesenteric, peritoneal, and/or omental nodules, although occasionally a poorly defined infiltrating mass is mistaken for sclerosing mesenteritis 62. A desmoplastic reaction (the growth of dense fibrous connective tissue that occurs around a tumor) may occur with some mesenteric cancers, with fibrotic retractions and deformity.

- Carcinoid tumor is often associated with focal bowel and liver lesions, but atypical cases with only mesenteric lesions have been seen.

- Mesenteric fibromatosis (desmoid tumors) are tumor-like fibromatoses, commonly seen in familial adenomatous polyposis 63. Desmoid tumors tend to be multifocal, have a noninflamed, mass-like and/or infiltrative appearance in the mesentery, and can encase vessels and intestine. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the preferred diagnostic test 64.

- Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis is a rare and serious complication of long-term peritoneal dialysis, although it can sometimes be idiopathic, where a fibrous layer thickens and encases the intestines, causing partial or complete bowel obstruction, malnutrition, and other gastrointestinal symptoms like pain, nausea, and vomiting 65. Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis is also associated with recurrent episodes of peritonitis. Diagnosis involves clinical signs, imaging, and a decline in dialysis efficiency. A cauliflower appearance of compressed bowel loops is a classic finding of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis, with the encasing and contrast-enhancing peritoneum creating a “cocoon” appearance. Pockets of ascites occur in 90%, and peritoneal calcifications in 70%. Intraperitoneal strands may cause the thickened bowel wall to appear trilaminar 65, 66. Treatment options include corticosteroids, tamoxifen, and, in severe cases, surgery.

- Retroperitoneal fibrosis is a rare condition where fibrous tissue builds up in the space behind the abdominal cavity from the distal aorta between L4 and L5 to the iliac arteries, leading to compression of organs like the kidneys, ureters, and major blood vessels 67. The most common form, idiopathic retroperitoneal fibrosis, has no clear cause, but other cases are linked to medications, infections, or cancer. Hydronephrosis and medial deviation of the proximal two-thirds of the ureters are common 68. Symptoms include lower back or flank pain (distinct from the focal abdominal pain seen in sclerosing mesenteritis), fatigue, weight loss, and difficulty urinating, while complications can involve kidney problems or impaired blood flow. Retroperitoneal fibrosis can look like sclerosing mesenteritis histologically, and patients can have both processes. Treatment may involve medications, surgery, or stents, and long-term monitoring is often necessary.

- Pseudomyxoma peritonei is a rare tumor that causes a buildup of jelly-like mucus in the abdomen and pelvis, with fluid loculated along peritoneal surfaces, leading to symptoms like abdominal swelling, pain, and constipation 69, 70. This classically results in a scalloped appearance of coated organs 71. Pseudomyxoma peritonei typically originates from a polyp in the appendix but can also start in other organs like the ovary or large intestine. The primary treatments are surgery to remove the tumors, often combined with chemotherapy called cytoreductive surgery (CRS) with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC).

- Other mesenteric processes that usually do not have the typical appearance of sclerosing mesenteritis include gastrointestinal stromal tumors, sarcomas, mesenteric edema (hypoalbuminemia, cirrhosis, congestive heart failure, trauma) and certain infections (mycobacteria, cryptococcus, schistosomiasis, HIV, and cholera) 31, 8

Sclerosing mesenteritis treatment

Currently, there are no official guidelines for the management of sclerosing mesenteritis, and recommendations are largely based on expert opinion. Sclerosing mesenteritis management is based on your signs and symptoms, with treatment generally reserved for individuals with symptoms.

Therapy of sclerosing mesenteritis is generally aimed toward symptom relief, because there is limited evidence that treatment can improve imaging or prevent complications 1. Accordingly, patients without symptoms are usually not treated 1. In several studies, only 1% to 6% of patients who presented with imaging findings of sclerosing mesenteritis required treatment 27, 8, 32. However, this figure may be higher in referral centers; in 2 large observational studies, approximately 50% received treatment initially, with more requiring treatment over time 50, 30. According to the American Gastroenterological Association, most patients with sclerosing mesenteritis are referred to gastroenterologists, and checkpoint inhibitor–associated sclerosing mesenteritis is divided between gastroenterologists and oncologists 1. Because the immune response is unknown and controlled trials are unavailable, drug selection in sclerosing mesenteritis is based on open-label studies or case reports. The American Gastroenterological Association suggested approach is shown in Figure 4 above. General measures include treating accompanying gastrointestinal disorders if present, such as constipation, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and/or irritable bowel syndrome. One of the American Gastroenterological Association associates routinely uses tricyclic antidepressants for the mild pain associated with sclerosing mesenteritis 72.

Medications

Medicines for sclerosing mesenteritis are used to control inflammation. Medicines may include:

- Corticosteroids. Corticosteroids such as prednisone control inflammation. Corticosteroids can be used alone but are usually combined with other medicines. They are not generally used for more than 3 to 4 months because of side effects.

- Hormone therapy. Hormone treatments such as tamoxifen (Soltamox)may slow the growth of scar tissue. Tamoxifen is typically combined with corticosteroids or other medicines and may be used long term. Tamoxifen increases the risk of blood clots and is typically combined with a daily aspirin to reduce this risk. Progesterone (Prometrium) may be used as an alternative to tamoxifen, but it also has significant side effects.

- Other medicines. Several other medicines have been used to treat sclerosing mesenteritis, such as azathioprine (Imuran, Azasan), colchicine (Colcrys, Mitigare), cyclophosphamide and thalidomide (Thalomid).

Corticosteroids

Prednisone monotherapy (30mg to 40 mg a day) may improve short-term symptoms, but long-term treatment is not advised because of side effects 30. In a large retrospective series of prednisone-treated patients, treatment was typically started at 40 mg a day, continued for 3 to 4 months, then tapered 5 mg/week 50. Any benefit is typically lost after drug discontinuation.

Tamoxifen

Tamoxifen is the most commonly used therapy for sclerosing mesenteritis at 10 mg twice daily, alone or together with prednisone 30mg to 40 mg daily 30. Initially chosen for its antifibrotic activity against transforming growth factor-beta because mesenteric fibrosis is the hallmark of more advanced disease, the actual tamoxifen mechanism of action is unknown. With combination therapy, prednisone is usually tapered after 3 months, and tamoxifen continued for maintenance, although how long to continue has not been determined 1.

Maximal response to prednisone and tamoxifen occurs around 4 to 6 months, with 50% to 60% of patients responding 30, 50. Tamoxifen side effects include antiestrogenic symptoms (hot flashes, sweating, vaginal bleeding), alopecia, fatigue, thrombosis, and laboratory abnormalities (thrombocytopenia, elevated liver enzymes). In responders with mild tamoxifen side effects, 10 mg daily may maintain response and improve tolerance 1. Contraindications to tamoxifen include a history of venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, or significant cerebrovascular, cardiovascular, or peripheral vascular disease 1. Active tobacco use is considered a relative contraindication 1.

Colchicine

Colchicine with prednisone has been used successfully, with a response rate of around 50% in a small series 30, 50, 73. Colchicine is prescribed at 0.6 mg twice a day with prednisone 40 mg daily, tapering prednisone after 3 months 50. Gastrointestinal side effects may limit colchicine use, and is contraindicated in kidney insufficiency 1.

Azathioprine

Azathioprine is typically dosed similar to inflammatory bowel disease (2 to 2.5 mg/kg/day) in patients who are normal thiopurine methyltransferase metabolizers 36, 74. A major limitation of azathioprine is a slow onset of action, so coadministration with prednisone is used early in therapy 1.

Other Immunosuppressants

Drugs with limited data include rituximab, thalidomide, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, infliximab, and ustekinumab 30, 50, 75, 39, 74, 76, 77, 78, 79. All of these agents have the potential for significant side effects, and thus are typically reserved as second-line therapies for severe, refractory disease 1.

Sclerosing mesenteritis surgery

There is no surgical cure for sclerosing mesenteritis 1. You may need surgery if the scar tissue blocks food from moving through your digestive tract (bowel obstruction) 80, 81, 82, 83, 84. In most, complete resection is impossible because of vascular compromise and disease extent.

Patients with chronic ischemia caused by mesenteric vascular obstruction are considered for revascularization. Few are candidates for endovascular revascularization because of the long length or distal location of the blood vessel 1. Surgical mesenteric revascularization is rarely feasible because of the extensive inflammatory disease 1.

Radiation therapy has had indefinite success 85, 86. Surgery does not cure sclerosing mesenteritis. In 1 study, only 10% of patients who underwent surgery required no additional treatment 30. Recurrent disease can be detected by radiologic findings or new clinical symptoms. In patients with persistent or recurrent symptoms following surgery, the American Gastroenterological Association suggest medical management similar to patients with nonobstructive symptoms 1.

Follow-up Imaging

Published recommendations for follow-up imaging because of concerns about associated cancer vary widely, from no repeat imaging, to annual repeating examinations up to 5 years 44, 46, 41, 49. In a meta-analysis of 4 case-control studies, an increased risk of cancer was not detectable 42, but another study reported a small long-term increased risk of lymphoma in those without initial features of malignancy, with 80% detectable in the first year 44. The second reason for repeat imaging is to assess progression of inflammation. Although the data are limited, except in the most severe cases, most patients—requiring treatment or not—achieve stable disease without radiologic progression after 2 years 50. During follow-up imaging, if any sclerosing mesenteritis features concerning for cancer occur, including significant growth in the mesenteric mass or new enlarged lymph node (lymphadenopathy), biopsy should be performed 45. For asymptomatic cases without initial features concerning for associated cancer, the American Gastroenterological Association suggest that patients be followed with annual CT scans for 2 years to ensure stability, and thereafter performed for concerning symptoms 1.

Sclerosing mesenteritis prognosis

Sclerosing mesenteritis prognosis is generally good, as it often has a benign and stable course, especially for asymptomatic individuals who may require no treatment 2. However, it can vary, and some cases may have a prolonged, debilitating, or even fatal outcome. Symptoms like abdominal pain can be managed with medical therapy, and surgery is typically reserved for severe cases of bowel obstruction that don’t respond to medication 1.

Sclerosing mesenteritis prognosis and course:

- Generally good: Many cases follow a benign or stable pattern, especially if asymptomatic.

- Variable course: Symptoms can range from mild to severe and can last from days to years.

- Fatal outcomes possible: While rare, disease progression and fatal outcomes have been reported.

- Spontaneous remission: In some cases, sclerosing mesenteritis can resolve on its own, which is considered the most favorable outcome.

Factors influencing sclerosing mesenteritis prognosis:

- Asymptomatic cases: Patients with no symptoms often have a very good prognosis and may not need any treatment.

- Symptomatic cases: Those with symptoms, such as chronic pain or complications, have a more variable prognosis and may benefit from medical or surgical intervention.

- Associated conditions: Sclerosing mesenteritis can be associated with other conditions like metabolic syndrome, obesity, and heart disease.

Whereas data are limited on the natural history of sclerosing mesenteritis, a systematic review of 192 sclerosing mesenteritis cases suggests that most cases (78.6%) have resolution of symptoms at follow-up (median of 10 months), but the all-cause mortality rate may be as high as 7.3% 31. It is unclear how many of these patients received treatment. Conversely, in the series with 92 cases, of the cohort that did not receive treatment, at a median 21-month follow-up, 26% remained asymptomatic and 74% had persistent but mild abdominal symptoms 30. However, of the 18 total deaths, 12 were patients who received no treatment 30. Taken together, the natural history of sclerosing mesenteritis is not well understood but may have an overall benign course for most cases.

- Worthington MT, Wolf JL, Crockett SD, Pardi DS. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Sclerosing Mesenteritis: Commentary. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025 May;23(6):902-907.e1. https://www.cghjournal.org/article/S1542-3565(25)00143-0/fulltext[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Saha B, Tome J, Wang XJ. Sclerosing Mesenteritis: A Concise Clinical Review for Clinicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2024 May;99(5):812-820. https://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org/article/S0025-6196(24)00083-1/fulltext[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Green MS, Chhabra R, Goyal H. Sclerosing mesenteritis: a comprehensive clinical review. Ann Transl Med. 2018 Sep;6(17):336. doi: 10.21037/atm.2018.07.01[↩][↩]

- Stephanie Ryan, Michelle McNicholas, Stephen J. Eustace. Anatomy for Diagnostic Imaging. (2011) Pages 208. ISBN: 9780702029714[↩]

- Expert tips for diagnosing and treating sclerosing mesenteritis. https://gastro.org/news/expert-tips-for-diagnosing-and-treating-sclerosing-mesenteritis/[↩]

- https://gastro.org/clinical-guidance/diagnosing-and-treating-sclerosing-mesenteritis/[↩]

- Bukiej, Aleksandra, A Case of Sclerosing Mesenteritis during Etanercept Therapy for Psoriatic Arthritis, Case Reports in Rheumatology, 2020, 8899658, 3 pages, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8899658[↩]

- Danford CJ, Lin SC, Wolf JL. Sclerosing Mesenteritis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019 Jun;114(6):867-873. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000167[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Avincsal, M. O., Otani, K., Kanzawa, M., Fujikura, K., Jimbo, N., Morinaga, Y., Hirose, T., Itoh, T., and Zen, Y. (2016) Sclerosing mesenteritis: A real manifestation or histological mimic of IgG4-related disease?. Pathology International, 66: 158–163. doi: 10.1111/pin.12386[↩]

- Nobili, C., Degrate, L., Caprotti, R., Franciosi, C., Leone, B. E., Romano, F., Dinelli, M., Uggeri, Fr., Extensive Sclerosing Mesenteritis of the Rectosigmoid Colon Associated with Erosive Colitis, Gastroenterology Research and Practice, 2009, 176793, 4 pages, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1155/2009/176793[↩]

- Minato, H., Shimizu, J., Arano, Y., Saito, K., Masunaga, T., Sakashita, T. and Nojima, T. (2012), IgG4-related sclerosing mesenteritis: A rare mesenteric disease of unknown etiology. Pathology International, 62: 281-286. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1827.2012.02805.x[↩]

- Ghanem, N., Pache, G., Bley, T., Kotter, E. and Langer, M. (2005), MR findings in a rare case of sclerosing mesenteritis of the mesocolon. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging, 21: 632-636. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.20280[↩]

- White, B., Kong, A. and Chang, A.-L. (2005), Sclerosing mesenteritis. Australasian Radiology, 49: 185-188. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1673.2005.01400.x[↩]

- Sharma, V., Martin, P. and Marjoniemi, V.-M. (2006), Idiopathic orbital inflammation with sclerosing mesenteritis: a new association?. Clinical & Experimental Ophthalmology, 34: 190-192. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-9071.2006.01182.x[↩]

- Bala, Anand, Coderre, Sylvain P, Johnson, Douglas RE, Nayak, V, Treatment of Sclerosing Mesenteritis with Corticosteroids and Azathioprine, Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 15, 462823, 3 pages, 2001. https://doi.org/10.1155/2001/462823[↩]

- Herrington JL, Jr, Edwards WH, Grossman LA. Mesenteric manifestations of Weber-Christian disease. Ann Surg 1961;154:949-55. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/instance/1465939/pdf/annsurg00860-0077.pdf[↩][↩]

- Ogden WW, 2nd, Bradburn DM, Rives JD. Pannicultis of the mesentery. Ann Surg 1960;151:659-68. 10.1097/00000658-196005000-00006[↩][↩]

- DeCastro JA, Calem WS, Papadakis L. Liposclerotic mesenteritis. Arch Surg. 1967 Jan;94(1):26-9. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1967.01330070028007[↩][↩]

- Jura V. Sulla mesenterite retratile e sclerosante. Policlinico (Sez Chir) 1924;31:575.[↩][↩]

- Emory TS, Monihan JM, Carr NJ, Sobin LH. Sclerosing mesenteritis, mesenteric panniculitis and mesenteric lipodystrophy: a single entity? Am J Surg Pathol. 1997 Apr;21(4):392-8. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199704000-00004[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Wat SY, Harish S, Winterbottom A, Choudhary AK, Freeman AH. The CT appearances of sclerosing mesenteritis and associated diseases. Clin Radiol. 2006 Aug;61(8):652-8. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2006.02.012[↩][↩]

- Badet N, Sailley N, Briquez C, Paquette B, Vuitton L, Delabrousse É. Mesenteric panniculitis: still an ambiguous condition. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2015 Mar;96(3):251-7. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2014.12.002[↩][↩][↩]

- Badet N, Sailley N, Briquez C, Paquette B, Vuitton L, Delabrousse É. Mesenteric panniculitis: still an ambiguous condition. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2015 Mar;96(3):251-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diii.2014.12.002[↩]

- Gunes SO, Akturk Y, Guldogan ES, Yilmaz KB, Ergun O, Hekimoglu B. Association between mesenteric panniculitis and non-neoplastic disorders. Clin Imaging. 2021 Nov;79:219-224. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2021.05.006[↩][↩]

- Kuhrmeier A. Mesenteriale Lipodystrophie [Mesenteric lipodystrophy]. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1985 Sep 7;115(36):1218-24. German.[↩]

- Sahin A, Artas H, Eroglu Y, Tunc N, Demirel U, Bahcecioglu IH, Yalniz M. An Overlooked Potentially Treatable Disorder: Idiopathic Mesenteric Panniculitis. Med Princ Pract. 2017;26(6):567-572. doi: 10.1159/000484605[↩]

- Daskalogiannaki M, Voloudaki A, Prassopoulos P, Magkanas E, Stefanaki K, Apostolaki E, Gourtsoyiannis N. CT evaluation of mesenteric panniculitis: prevalence and associated diseases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000 Feb;174(2):427-31. doi: 10.2214/ajr.174.2.1740427[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Protin-Catteau L, Thiéfin G, Barbe C, Jolly D, Soyer P, Hoeffel C. Mesenteric panniculitis: review of consecutive abdominal MDCT examinations with a matched-pair analysis. Acta Radiol. 2016 Dec;57(12):1438-1444. doi: 10.1177/0284185116629829[↩][↩]

- Atacan H, Erkut M, Değirmenci F, Akkaya S, Fidan S, Coşar AM. A Single Tertiary Center 14-year Experience With Mesenteric Panniculitis in Turkey: A Retrospective Study of 716 Patients. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2023 Feb;34(2):140-147. doi: 10.5152/tjg.2023.22514[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Akram S, Pardi DS, Schaffner JA, Smyrk TC. Sclerosing mesenteritis: clinical features, treatment, and outcome in ninety-two patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007 May;5(5):589-96; quiz 523-4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.02.032[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Sharma P, Yadav S, Needham CM, Feuerstadt P. Sclerosing mesenteritis: a systematic review of 192 cases. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2017 Apr;10(2):103-111. doi: 10.1007/s12328-017-0716-5[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Horton KM, Lawler LP, Fishman EK. CT findings in sclerosing mesenteritis (panniculitis): spectrum of disease. Radiographics. 2003 Nov-Dec;23(6):1561-7. doi: 10.1148/rg.1103035010[↩][↩]

- Patel N, Saleeb SF, Teplick SK. General case of the day. Mesenteric panniculitis with extensive inflammatory involvement of the peritoneum and intraperitoneal structures. Radiographics. 1999 Jul-Aug;19(4):1083-5. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.19.4.g99jl221083[↩]

- Kaya C, Bozkurt E, Yazıcı P, İdiz UO, Tanal M, Mihmanlı M. Approach to the diagnosis and treatment of mesenteric panniculitis from the surgical point of view. Turk J Surg. 2018 Jul 1;34(2):121-124. doi: 10.5152/turkjsurg.2018.3881[↩]

- Rajendran B, Duerksen DR. Retractile mesenteritis presenting as protein-losing gastroenteropathy. Can J Gastroenterol. 2006 Dec;20(12):787-9. doi: 10.1155/2006/507923[↩][↩]

- Nyberg L, Björk J, Björkdahl P, Ekberg O, Sjöberg K, Vigren L. Sclerosing mesenteritis and mesenteric panniculitis – clinical experience and radiological features. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017 Jun 13;17(1):75. doi: 10.1186/s12876-017-0632-7[↩][↩][↩]

- Liu Z, Jiao Y, He L, Wang H, Wang D. A rare case report of immunoglobulin G4-related sclerosing mesenteritis and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020 Oct 9;99(41):e22579. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000022579[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Coulier B. Mesenteric panniculitis. Part 1: MDCT–pictorial review. JBR-BTR. 2011 Sep-Oct;94(5):229-40. doi: 10.5334/jbr-btr.658[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Ginsburg PM, Ehrenpreis ED. A pilot study of thalidomide for patients with symptomatic mesenteric panniculitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002 Dec;16(12):2115-22. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01383.x[↩][↩][↩]

- Misty mesentery sign. https://radiopaedia.org/cases/misty-mesentery-sign#image-64522986[↩]

- van Putte-Katier N, van Bommel EF, Elgersma OE, Hendriksz TR. Mesenteric panniculitis: prevalence, clinicoradiological presentation and 5-year follow-up. Br J Radiol. 2014 Dec;87(1044):20140451. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20140451[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Hussain I, Ishrat S, Aravamudan VM, Khan SR, Mohan BP, Lohan R, Abid MB, Ang TL. Mesenteric panniculitis does not confer an increased risk for cancers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022 Apr 29;101(17):e29143. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000029143[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Gögebakan Ö, Albrecht T, Osterhoff MA, Reimann A. Is mesenteric panniculitis truely a paraneoplastic phenomenon? A matched pair analysis. Eur J Radiol. 2013 Nov;82(11):1853-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2013.06.023[↩]

- Grégory J, Dana J, Yang I, Chong J, Drevon L, Ronot M, Vilgrain V, Reinhold C, Gallix B. CT features associated with underlying malignancy in patients with diagnosed mesenteric panniculitis. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2022 Sep;103(9):394-400. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2022.06.009[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Ehrenpreis ED, Roginsky G, Gore RM. Clinical significance of mesenteric panniculitis-like abnormalities on abdominal computerized tomography in patients with malignant neoplasms. World J Gastroenterol. 2016 Dec 28;22(48):10601-10608. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i48.10601[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Corwin MT, Smith AJ, Karam AR, Sheiman RG. Incidentally detected misty mesentery on CT: risk of malignancy correlates with mesenteric lymph node size. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2012 Jan-Feb;36(1):26-9. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e3182436c4d[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Nakatani K, Nakamoto Y, Togashi K. FDG-PET/CT assessment of misty mesentery: feasibility for distinguishing viable mesenteric malignancy from stable conditions. Eur J Radiol. 2013 Aug;82(8):e380-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2013.03.016[↩][↩]

- Kuang AG, Sperling G, Liang TZ, Lu Y, Tan D, Bollin K, Johnson DB, Manzano JM, Shatila M, Thomas AS, Thompson JA, Zhang HC, Wang Y. Sclerosing mesenteritis following immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023 Sep;149(11):9221-9227. doi: 10.1007/s00432-023-04802-2[↩]

- Smith ZL, Sifuentes H, Deepak P, Ecanow DB, Ehrenpreis ED. Relationship between mesenteric abnormalities on computed tomography and malignancy: clinical findings and outcomes of 359 patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013 May-Jun;47(5):409-14. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3182703148[↩][↩]

- Cortés P, Ghoz HM, Mzaik O, Alhaj Moustafa M, Bi Y, Brahmbhatt B, Daoud N, Pang M. Colchicine as an Alternative First-Line Treatment of Sclerosing Mesenteritis: A Retrospective Study. Dig Dis Sci. 2022 Jun;67(6):2403-2412. doi: 10.1007/s10620-021-07081-4[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Nomura S, Shimojima Y, Yoshizawa E, Kondo Y, Kishida D, Sekijima Y. Mesenteric panniculitis in systemic lupus erythematosus showing characteristic computed tomography findings. Lupus. 2021 Jul;30(8):1358-1359. doi: 10.1177/09612033211020363[↩]

- Chawla S, Yalamarthi S, Shaikh IA, Tagore V, Skaife P. An unusual presentation of sclerosing mesenteritis as pneumoperitoneum: case report with a review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2009 Jan 7;15(1):117-20. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.117[↩]

- Borde JP, Offensperger WB, Kern WV, Wagner D. Mycobacterium genavense specific mesenteritic syndrome in HIV-infected patients: a new entity of retractile mesenteritis? AIDS. 2013 Nov 13;27(17):2819-22. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000433820.25415.17[↩]

- Alonso Socas MM, Valls RA, Gómez Sirvent JL, López Lirola A, Aix SP, Higuera AC, Santolaria F. Mesenteric panniculitis by cryptococcal infection in an HIV-infected man without severe immunosuppression. AIDS. 2006 Apr 24;20(7):1089-90. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000222093.05400.bb[↩]

- Rozin A, Bishara B, Ben-Izhak O, Fischer D, Carter A, Edoute Y. Fibrosing omental panniculitis and polyserositis associated with long-term treatment by paroxetine. Isr Med Assoc J. 2000 Sep;2(9):714-6. https://www.ima.org.il/FilesUploadPublic/IMAJ/0/63/31618.pdf[↩]

- Rosón N, Garriga V, Cuadrado M, Pruna X, Carbó S, Vizcaya S, Peralta A, Martinez M, Zarcero M, Medrano S. Sonographic findings of mesenteric panniculitis: correlation with CT and literature review. J Clin Ultrasound. 2006 May;34(4):169-76. doi: 10.1002/jcu.20214[↩]

- Fujiyoshi F, Ichinari N, Kajiya Y, Nishida H, Shimura T, Nakajo M, Matsunaga Y, Furoi A, Imaguma M. Retractile mesenteritis: small-bowel radiography, CT, and MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997 Sep;169(3):791-3. doi: 10.2214/ajr.169.3.9275898[↩]

- Zissin R, Metser U, Hain D, Even-Sapir E. Mesenteric panniculitis in oncologic patients: PET-CT findings. Br J Radiol. 2006 Jan;79(937):37-43. doi: 10.1259/bjr/29320216[↩][↩]

- McLaughlin PD, Filippone A, Maher MM. The “misty mesentery”: mesenteric panniculitis and its mimics. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013 Feb;200(2):W116-23. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.8493[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Ezhapilli SR, Moreno CC, Small WC, Hanley K, Kitajima HD, Mittal PK. Mesenteric masses: approach to differential diagnosis at MRI with histopathologic correlation. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2014 Oct;40(4):753-69. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24690[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- McLaughlin PD, Filippone A, Maher MM. The “misty mesentery”: mesenteric panniculitis and its mimics. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013 Feb;200(2):W116-23. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.8493). To distinguish the two, it is important to look for characteristics more specific to lymphoma: diffuse, larger size, or extra-mesenteric lymphadenopathy; hepatosplenomegaly; cytopenias; and evidence of a paraneoplastic syndrome, such as hypercalcemia ((Ezhapilli SR, Moreno CC, Small WC, Hanley K, Kitajima HD, Mittal PK. Mesenteric masses: approach to differential diagnosis at MRI with histopathologic correlation. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2014 Oct;40(4):753-69. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24690[↩]

- Veron Sanchez A, Bennouna I, Coquelet N, Cabo Bolado J, Pinilla Fernandez I, Mullor Delgado LA, Pezzullo M, Liberale G, Gomez Galdon M, Bali MA. Unravelling Peritoneal Carcinomatosis Using Cross-Sectional Imaging Modalities. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023 Jul 3;13(13):2253. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics13132253[↩]

- Nieuwenhuis MH, Lefevre JH, Bülow S, Järvinen H, Bertario L, Kernéis S, Parc Y, Vasen HF. Family history, surgery, and APC mutation are risk factors for desmoid tumors in familial adenomatous polyposis: an international cohort study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011 Oct;54(10):1229-34. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e318227e4e8[↩]

- Lee JC, Thomas JM, Phillips S, Fisher C, Moskovic E. Aggressive fibromatosis: MRI features with pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006 Jan;186(1):247-54. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.1674[↩]

- Danford CJ, Lin SC, Smith MP, Wolf JL. Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2018 Jul 28;24(28):3101-3111. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i28.3101[↩][↩]

- López Grove R, Heredia Martínez A, Aineseder M, de Paula JA, Ocantos JA. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis: imaging findings in an uncommon entity. Radiologia (Engl Ed). 2019 Sep-Oct;61(5):388-395. English, Spanish. doi: 10.1016/j.rx.2019.02.005[↩]

- Engelsgjerd JS, Leslie SW, LaGrange CA. Retroperitoneal Fibrosis. [Updated 2024 Aug 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482409[↩]

- Peisen F, Thaiss WM, Ekert K, Horger M, Amend B, Bedke J, Nikolaou K, Kaufmann S. Retroperitoneal Fibrosis and its Differential Diagnoses: The Role of Radiological Imaging. Rofo. 2020 Oct;192(10):929-936. English, German. doi: 10.1055/a-1181-9205[↩]

- Askar A, Arpat A, Durgun V. Pseudomyxoma peritonei: The struggle of a lifetime and the hope of a cure – a rare diagnosis with review of the literature. North Clin Istanb. 2024 Jun 28;11(3):261-268. doi: 10.14744/nci.2023.50374[↩]

- Morera-Ocon FJ, Navarro-Campoy C. History of pseudomyxoma peritonei from its origin to the first decades of the twenty-first century. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2019 Sep 27;11(9):358-364. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v11.i9.358[↩]

- Vicens RA, Patnana M, Le O, Bhosale PR, Sagebiel TL, Menias CO, Balachandran A. Multimodality imaging of common and uncommon peritoneal diseases: a review for radiologists. Abdom Imaging. 2015 Feb;40(2):436-56. doi: 10.1007/s00261-014-0224-8[↩]

- Pardi, D.S. Tricyclic antidepressant use for mild pain in sclerosing mesenteritis personal communication, 2024[↩]

- Iwanicki-Caron I, Savoye G, Legros JR, Savoye-Collet C, Herve S, Lerebours E. Successful management of symptoms of steroid-dependent mesenteric panniculitis with colchicine. Dig Dis Sci. 2006 Jul;51(7):1245-9. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-8044-5[↩]

- Bala A, Coderre SP, Johnson DR, Nayak V. Treatment of sclerosing mesenteritis with corticosteroids and azathioprine. Can J Gastroenterol. 2001 Aug;15(8):533-5. doi: 10.1155/2001/462823[↩][↩]

- Archer S, Pereira-Guedes T, Fonseca T, Carvalho Sá D, Pedroto I. A Rare Cause of Abdominal Pain: IgG4-Related Sclerosing Mesenteritis. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2023 Jun 22;32(2):141. doi: 10.15403/jgld-4921[↩]

- Viswanathan V, Murray KJ. Idiopathic sclerosing mesenteritis in paediatrics: Report of a successfully treated case and a review of literature. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2010 Jan 21;8:5. doi: 10.1186/1546-0096-8-5[↩]

- Rothlein LR, Shaheen AW, Vavalle JP, Smith SV, Renner JB, Shaheen NJ, Tarrant TK. Sclerosing mesenteritis successfully treated with a TNF antagonist. BMJ Case Rep. 2010 Dec 20;2010:bcr0720103145. doi: 10.1136/bcr.07.2010.3145[↩]

- Byriel B, Walker M, Fischer M. Sclerosing Mesenteritis Complicated With Mesenteric Lymphoma Responsive to Ustekinumab. ACG Case Rep J. 2022 May 25;9(5):e00757. doi: 10.14309/crj.0000000000000757[↩]

- Bush RW, Hammar SP, Rudolph RH. Sclerosing Mesenteritis: Response to Cyclophosphamide. Arch Intern Med. 1986;146(3):503–505. doi:10.1001/archinte.1986.00360150113013[↩]

- Durst AL, Freund H, Rosenmann E, Birnbaum D. Mesenteric panniculitis: review of the leterature and presentation of cases. Surgery. 1977 Feb;81(2):203-11.[↩]

- Kipfer RE, Moertel CG, Dahlin DC. Mesenteric lipodystrophy. Ann Intern Med. 1974 May;80(5):582-8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-80-5-582[↩]

- Monahan DW, Poston WK Jr, Brown GJ. Mesenteric panniculitis. South Med J. 1989 Jun;82(6):782-4. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198906000-00029[↩]

- Parra-Davila E, McKenney MG, Sleeman D, Hartmann R, Rao RK, McKenney K, Compton RP. Mesenteric panniculitis: case report and literature review. Am Surg. 1998 Aug;64(8):768-71.[↩]

- Soergel KH, Hensley GT. Fatal mesenteric panniculitis. Gastroenterology. 1966 Oct;51(4):529-36.[↩]

- Han SY, Koehler RE, Keller FS, Ho KJ, Zornes SL. Retractile mesenteritis involving the colon: pathologic and radiologic correlation (case report). AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1986 Aug;147(2):268-70. doi: 10.2214/ajr.147.2.268[↩]

- OGDEN WW 2nd, BRADBURN DM, RIVES JD. MESENTERIC PANNICULITIS: REVIEW OF 27 CASES. Ann Surg. 1965 Jun;161(6):864-75. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/instance/1409094/pdf/annsurg00933-0050.pdf[↩]