Contents

- Coronary artery disease

- Coronary artery disease symptoms

- Coronary artery disease complications

- Coronary artery disease causes

- Coronary artery disease prevention

- Coronary artery disease diagnosis

- Coronary artery disease treatment

- Living with coronary artery disease

- Coronary artery disease prognosis

Coronary artery disease

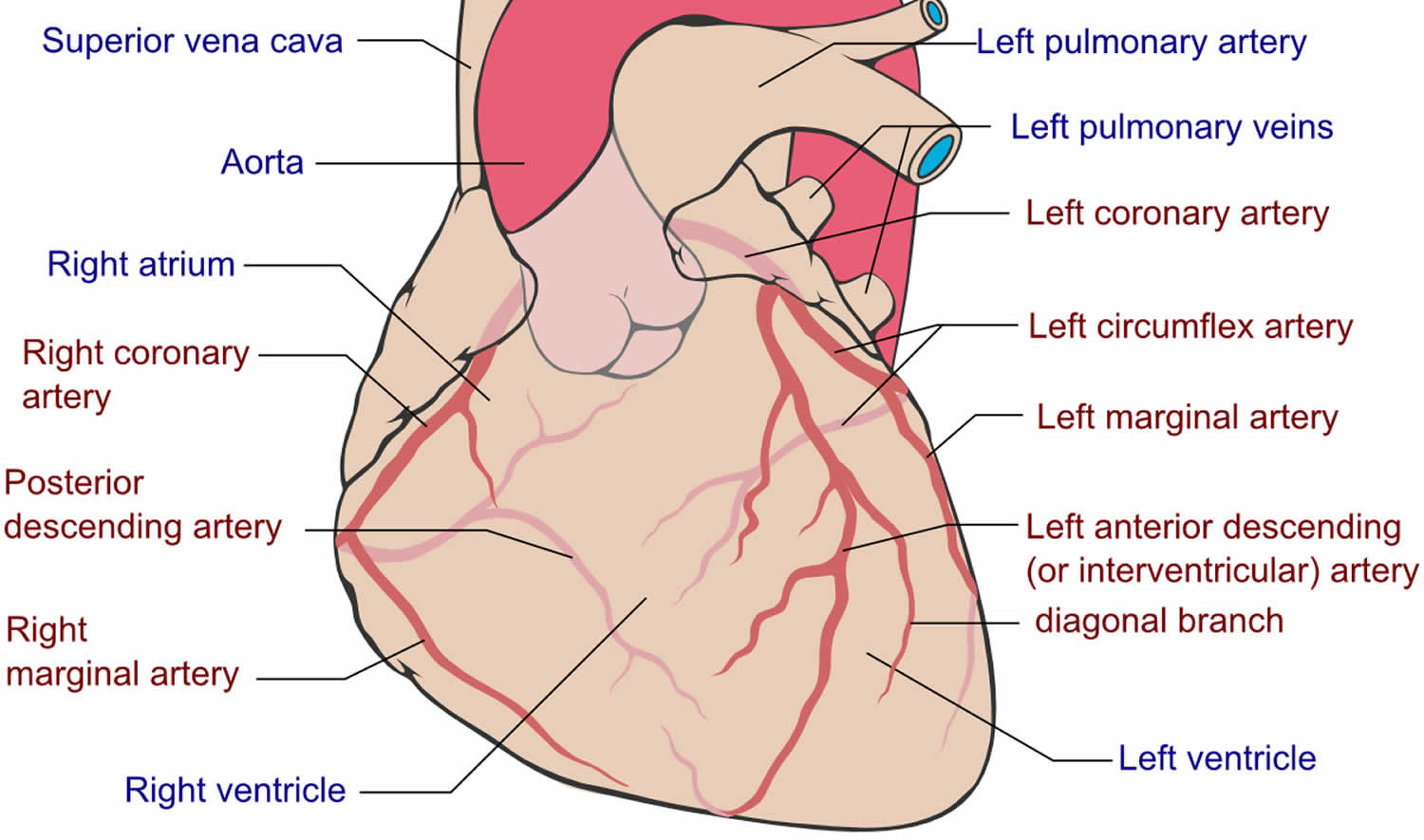

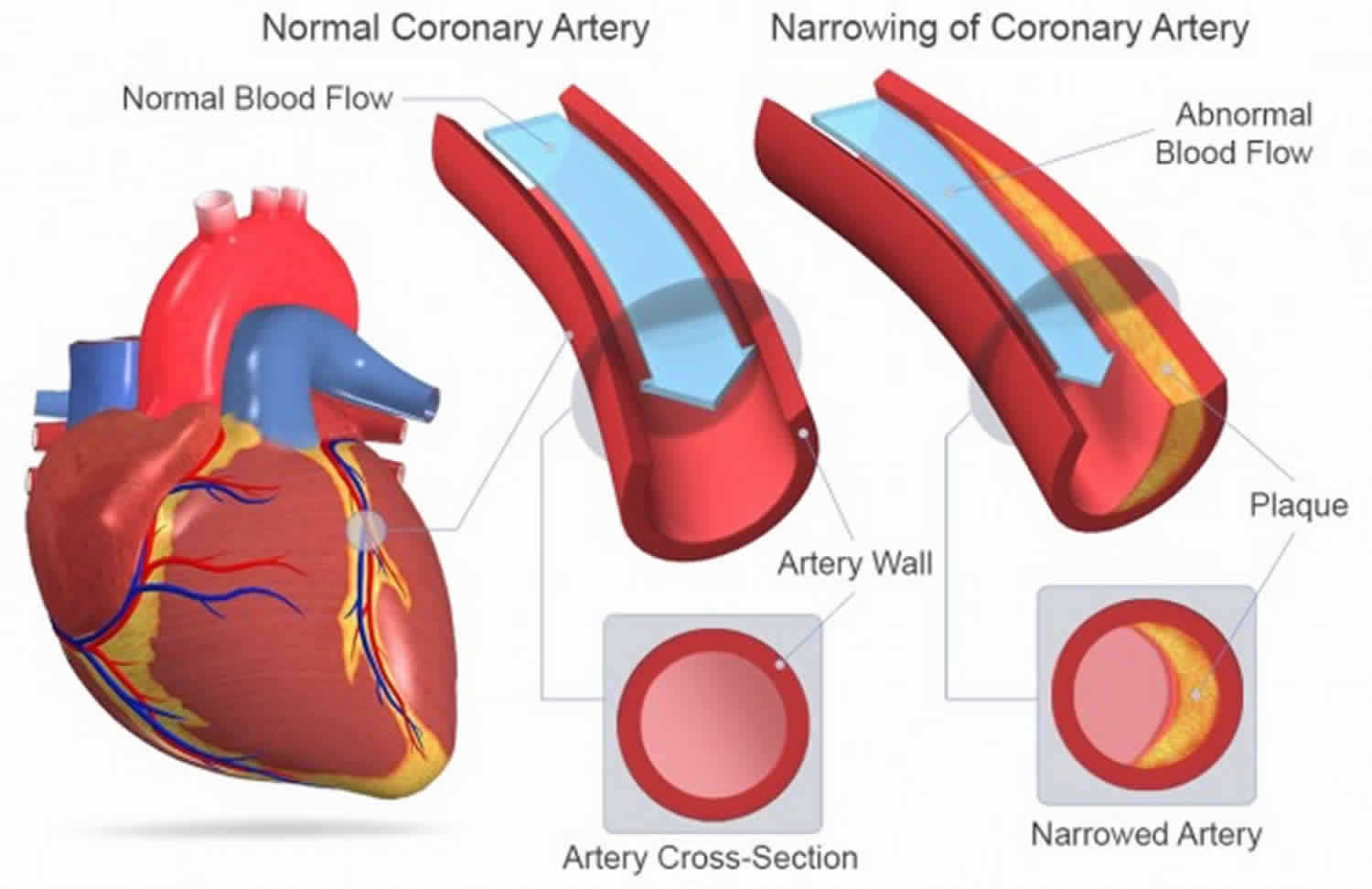

Coronary artery disease (CAD) also called coronary heart disease (CHD) or ischemic heart disease, is a type of heart disease where the coronary arteries that supply oxygen and blood to your heart become hardened and narrowed due to the buildup of fatty substances, cholesterol, cellular waste products, calcium, and fibrin, called plaque (atheroma), on their inner walls. This buildup is called atherosclerosis. As it grows, less blood can flow through the coronary arteries. As a result, the heart muscle can’t get the blood or oxygen it needs. This can lead to chest pain (angina) or a heart attack. Angina is a symptom of coronary heart disease (coronary artery disease), where you experience chest pain, pressure or discomfort when there is not enough blood flowing to your heart muscle that occurs if an area of heart muscle is starved of oxygen-rich blood. A heart attack happens when blood flow to the heart suddenly becomes blocked. Without the blood coming in, the heart can’t get oxygen. If not treated quickly, the heart muscle begins to die. Most heart attacks happen when a blood clot suddenly cuts off the hearts’ blood supply, causing permanent heart damage. Over time, coronary artery disease can also weaken your heart muscle and contribute to heart failure and arrhythmias (irregular heartbeats). Heart failure means the heart can’t pump blood well to the rest of the body. Arrhythmias are changes in the normal beating rhythm of the heart.

Other names for coronary heart disease 1:

- Atherosclerosis

- Coronary artery disease

- Hardening of the arteries

- Heart disease

- Ischemic heart disease

- Narrowing of the arteries

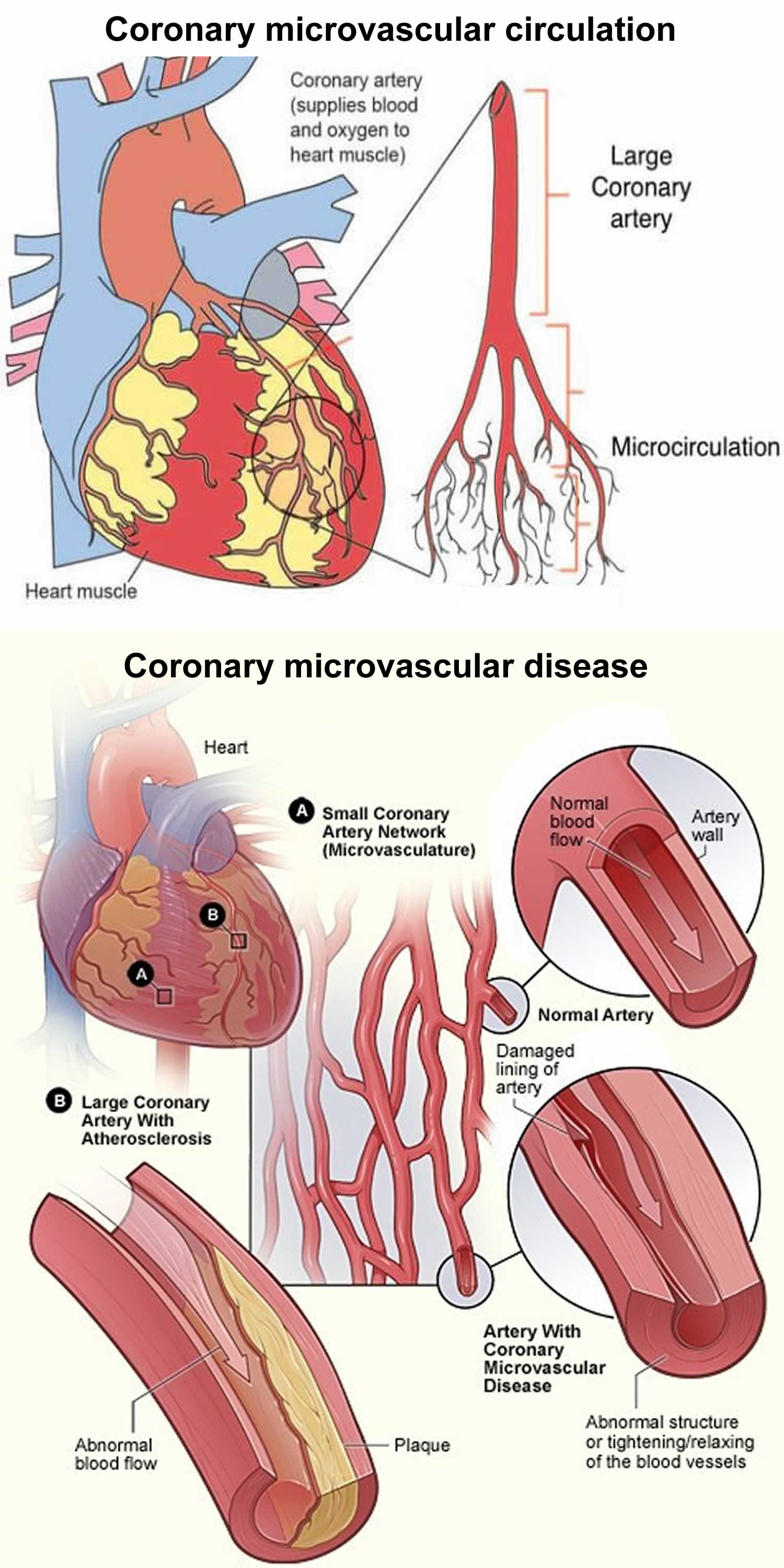

Coronary artery disease (coronary heart disease) affects the larger coronary arteries on the surface of your heart. Another type of coronary heart disease is called coronary microvascular disease, which affects the tiny arteries in the heart muscle. Coronary microvascular disease is more common in women and it’s theorized to be due to the heart’s tiny blood vessels not working normally.

Coronary heart disease (coronary artery disease) and its complications, like arrhythmia (irregular heartbeats), angina pectoris, and heart attack (also called myocardial infarction), are the leading causes of death in the United States, which peaked in the mid-1960s and then decreased, however, it still is the leading cause of death worldwide 2. In one study, it was estimated that coronary artery disease represented 2.2% of the overall global burden of disease and 32.7% of cardiovascular diseases 3. About 18.2 million American adults have coronary artery disease (coronary heart disease), making it the most common type of heart disease in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 4, 5. About 366,000 Americans die from coronary heart disease each year 6. More women than men have died annually from ischemic heart disease since 1984, and coronary artery disease (coronary heart disease) is the cause of over 250,000 deaths in women each year 7.

The cause of coronary artery disease depends on the type. Coronary artery disease is often caused by cholesterol, a waxy substance that builds up inside the lining of the coronary arteries forming plaque. This buildup can partially or totally block blood flow in the large arteries of the heart.

Smoking or having high blood pressure, high cholesterol, diabetes, obesity or a strong family history of heart disease makes you more likely to get coronary artery disease (coronary heart disease). If you’re at high risk of coronary artery disease, talk to your doctor. You may need tests to check for narrowed arteries and coronary artery disease. For most people, coronary heart disease is preventable with a heart-healthy lifestyle.

Coronary heart disease is largely preventable. Studies show that heart-healthy living — never smoking or quitting smoking if you do smoke, eating healthy, and being physically active — throughout life can prevent coronary heart disease and its complications. A heart-healthy lifestyle is important for people of all ages. But it is especially important for anyone who has other risk factors for heart disease. Work with your healthcare provider to set up a plan that works for you based on your lifestyle, your home and neighborhood environments, and your culture. This may mean taking steps to improve your diet, get physically active, manage other medical conditions, and help you quit smoking.

Symptoms of coronary heart disease may be different from person to person even if they have the same type of coronary heart disease. However, because many people have no symptoms, they do not know they have coronary heart disease until they have chest pain, blood flow to the heart is blocked causing a heart attack, or the heart suddenly stops working, also known as cardiac arrest.

If you have coronary heart disease, you may need heart-healthy lifestyle changes, medicines, surgery, or a combination of these approaches to your condition and prevent serious problems.

Figure 1. Coronary arteries supplying blood, oxygen & nutrients to your heart

Figure 2. Atherosclerosis blocking the coronary artery in the heart

Figure 3. Coronary microvascular disease

Angina is also called angina pectoris, is a heart condition that causes chest pain, pressure or discomfort you feel when there is not enough blood flowing to your heart muscle. You may also feel the discomfort in your neck, jaw, shoulder, back, arms or stomach. People sometimes describe the feeling as a dull ache. Angina symptoms are not the same for everyone. Some people may feel the pain or tightness only in their arm, neck, stomach or jaw. For some people the chest pain or tightness is severe, while others may feel nothing more than a mild discomfort or pressure. Angina usually happens during activities like walking, climbing stairs, exercising, or cleaning or when someone is upset. Angina can be a symptom of coronary artery disease (coronary heart disease).

Angina can be a warning sign that you are at increased risk of a heart attack. If your chest pain lasts longer than a few minutes and doesn’t go away when you rest or take your angina medications, it may be a sign you’re having a heart attack. Call your local emergency services number or emergency medical help. Only drive yourself to the hospital if there is no other transportation option.

If chest discomfort is a new symptom for you, it’s important to see your doctor to determine the cause and to get proper treatment. If you’ve been diagnosed with stable angina and it gets worse or changes, seek medical help immediately.

The chest pain that occurs with angina can make doing some activities, such as walking, uncomfortable. However, the most dangerous angina complication is a heart attack.

Warning signs and symptoms of a heart attack include:

- Pressure, fullness or a squeezing pain in the center of the chest that lasts for more than a few minutes

- Pain extending beyond the chest to the shoulder, arm, back, or even to the teeth and jaw

- Fainting

- Impending sense of doom

- Increasing episodes of chest pain

- Nausea and vomiting

- Continued pain in the upper belly area (abdomen)

- Shortness of breath

- Sweating

If you have any of these symptoms, seek emergency medical attention immediately.

What is angina?

Angina is also called angina pectoris, is a heart condition that causes chest pain, pressure or discomfort you feel when there is not enough blood flowing to your heart muscle. You may also feel the discomfort in your neck, jaw, shoulder, back, arms or stomach. People sometimes describe the feeling as a dull ache. Angina symptoms are not the same for everyone. Some people may feel the pain or tightness only in their arm, neck, stomach or jaw. For some people the chest pain or tightness is severe, while others may feel nothing more than a mild discomfort or pressure. Angina usually happens during activities like walking, climbing stairs, exercising, or cleaning or when someone is upset. Angina can be a symptom of coronary artery disease (coronary heart disease). This occurs when the coronary arteries that carry blood to your heart become narrowed and blocked because of atherosclerosis (thickening or hardening of the arteries caused by a buildup of plaque, which are made up of deposits of fatty substances, cholesterol, cellular waste products, calcium, and fibrin) or a blood clot. Angina pectoris can also occur because of unstable plaques, poor blood flow through a narrowed heart valve, a decreased pumping function of the heart muscle, as well as a coronary artery spasm. The amount of pain or discomfort you feel does not always reflect how badly your coronary arteries are affected. Angina goes away after a few minutes. However, you should go to the emergency room if you have chest pain that won’t go away. If your chest pain lasts longer than 5 minutes, call your local emergency services number and ask for an ambulance.

Angina symptoms may include:

- Chest pain, dull ache or discomfort often described as squeezing, pressure or tightness

- Intense sweating

- Difficulty catching your breath or shortness of breath

- Pain in your arms, neck, jaw, shoulder or back, even if you don’t have pain in the chest

- Nausea

- Fatigue (feeling overly tired)

- Dizziness

- The feeling of gas or indigestion

- Pain that comes and goes

If you have any of these symptoms, see your doctor. Although angina is relatively common, it can still be hard to distinguish from other types of chest pain, such as the discomfort of indigestion or muscular pain. If you have unexplained chest pain, it’s very important you seek medical help right away, so that your doctor can assess you to find out why you are getting the pain.

- If you have any symptoms of angina, immediately stop, sit down and rest. If your symptoms are still there once you’ve stopped, take your usual angina medication, if you have some.

- If the symptoms are still there in 5 minutes, repeat the dose. Tell someone how you’re feeling, whether that’s by phone or simply the nearest person.

- If the symptoms are getting worse, or are still there in 5 more minutes, call your local emergency services number and ask for an ambulance.

- Chew an adult aspirin tablet (300mg) if there is one easily available, unless you’re allergic to aspirin or have been told not to take it. If you don’t have an aspirin next to you, or if you don’t know if you’re allergic to aspirin, just stay resting until the ambulance arrives.

The chest pain that occurs with angina can make doing some activities, such as walking, uncomfortable. However, the most dangerous angina complication is a heart attack. A heart attack is when a part of the heart muscle suddenly loses its blood supply. This is usually due to coronary heart disease.

Warning signs and symptoms of a heart attack include:

- Pressure, fullness or a squeezing pain in the center of the chest that lasts for more than a few minutes

- Pain extending beyond the chest to the shoulder, arm, back, or even to the teeth and jaw

- Fainting

- Impending sense of doom

- Increasing episodes of chest pain

- Nausea and vomiting

- Continued pain in the upper belly area (abdomen)

- Shortness of breath

- Sweating

If you have any of these symptoms, seek emergency medical attention immediately.

To diagnose angina, your doctor will ask you about your signs and symptoms and may run blood tests, take an X-ray, or order tests, such as an electrocardiogram (EKG or ECG), an exercise stress test, or cardiac catheterization, to determine how well your heart is working.

With some types of angina, you may need emergency medical treatment to try to prevent a heart attack. To control your condition, your doctor may recommend heart-healthy lifestyle changes, medicines (glyceryl trinitrate or GTN), medical procedures, and cardiac rehabilitation.

Types of angina

There are three types of angina. The type depends on the cause and whether rest or medication relieve symptoms:

- Stable angina or angina pectoris. Stable angina is the most common type of angina. The term angina pectoris is derived from Latin, meaning “strangling of the chest” 8. Stable angina (angina pectoris) occurs when your heart muscle is not getting enough blood flow during periods of physical activity. Stable angina has a regular pattern. Stable angina is usually treated over a longer period. Treatment includes medicines as well as a gradual reintroduction to exercise. This is offered as part of a cardiac rehabilitation program. This improves your heart’s activity and can reduce risk factors that help the condition progress.

- Unstable angina. Unstable angina is the most serious angina and it’s a medical emergency. Unstable angina can be a warning of a heart attack. Unstable angina is when you have symptoms that you have developed for the first time, or angina which was previously stable but has recently got worse or changed in pattern. Unstable angina can occur without warning—even when you are not being physically active or with less stress than usual, and may even come on while you are resting. And it does not follow a pattern. Unstable angina lasts longer than stable angina. Rest and medicine do not relieve unstable angina.

- Variant angina or Prinzmetal’s angina. Variant angina (Prinzmetal’s angina) is rare. Variant angina (Prinzmetal’s angina) typically happens during the night or early morning when you are at rest. Variant angina can cause severe pain. Medicines can help.

- Refractory angina. Refractory angina episodes are frequent despite a combination of medications and lifestyle changes.

Stable angina

Stable angina also known as angina pectoris, is a type of chest pain, pressure or discomfort you feel when blood flow to your heart is reduced, preventing the heart muscle from receiving enough oxygen. The reduced blood flow is usually the result of a partial or complete blockage of your heart’s arteries (coronary arteries). Stable angina (angina pectoris) usually occurs in individuals with atherosclerosis (thickening or hardening of the arteries caused by a buildup of plaque, which are made up of deposits of fatty substances, cholesterol, cellular waste products, calcium, and fibrin) whose coronary arteries have been narrowed as a result. The chest pain is typically brought on physical activity (exertion) or emotional stress and does not occur at rest. For example, chest pain, pressure or discomfort that comes on when you’re walking uphill or in the cold weather may be angina. Stable angina pain is predictable and usually similar to previous episodes of chest pain. The chest pain typically lasts a short time, perhaps five minutes or less.

Stable angina is completely relieved by rest or the administration of sublingual nitroglycerine.

There are 2 other forms of angina pectoris. They are:

- Variant angina pectoris or Prinzmetal’s angina

- Microvascular angina or nonobstructive coronary heart disease

Unstable angina

Unstable angina sometimes referred to as acute coronary syndrome causes unexpected chest pain, and usually occurs while resting. Unstable angina is the most serious angina and it’s a medical emergency, since it can progress to a heart attack 9. Medical attention may be needed right away to restore blood flow to the heart muscle. Unstable angina is unpredictable and occurs at rest. Unstable angina may be new or occur more often and be more severe than stable angina. Unstable angina can also occur with or without physical exertion or occurs with less physical effort. Unstable angina is chest pain that is sudden and often gets worse over a short period of time. It’s typically severe and lasts longer than stable angina, maybe 20 minutes or longer. The pain doesn’t go away with rest or the usual angina medications. If the blood flow doesn’t improve, the heart is starved of oxygen and a heart attack occurs. Unstable angina is dangerous and requires emergency treatment.

You may be developing unstable angina if your chest pain:

- Starts to feel different, is more severe, comes more often, or occurs with less activity or while you are at rest

- Lasts longer than 15 to 20 minutes

- Occurs without cause (for example, while you are asleep or sitting quietly)

- Does not respond well to a medicine called nitroglycerin (especially if this medicine worked to relieve chest pain in the past)

- Occurs with a drop in blood pressure or shortness of breath

Unstable angina is a warning sign that a heart attack may happen soon and needs to be treated right away. See your health care provider if you have any type of chest pain.

Coronary artery disease due to atherosclerosis is the most common cause of unstable angina 10. Atherosclerosis is the buildup of fatty material, called plaque, along the walls of the arteries. This causes arteries to become narrowed and less flexible. The narrowing can reduce blood flow to the heart, causing chest pain. The most common cause of unstable angina is due to coronary artery narrowing due to a blood clots that block an artery partially or totally that develops on a disrupted atherosclerotic plaque and is nonocclusive 10. Blood clots may form, partially dissolve, and later form again and angina can occur each time a clot blocks blood flow in an artery.

Rare causes of angina are 9:

- Abnormal function of tiny branch arteries without narrowing of larger arteries (called microvascular dysfunction or cardiac syndrome X)

- Coronary artery spasm (Prinzmetal’s angina). Endothelial or vascular smooth dysfunction causes vasospasm of a coronary artery 11

Unstable angina results when the blood flow is impeded to the heart muscle (myocardium). Most commonly, this block can be from intraluminal plaque formation, intraluminal thrombosis, vasospasm, and elevated blood pressure. Often a combination of these is the provoking factor.

Unstable angina is a sign of more severe heart disease. Unstable angina may lead to:

- Abnormal heart rhythms (arrhythmias)

- A heart attack

- Heart failure

How well you do depends on many different things, including:

- How many and which arteries in your heart are blocked, and how severe the blockage is

- If you have ever had a heart attack

- How well your heart muscle is able to pump blood out to your body

Abnormal heart rhythms and heart attacks can cause sudden death.

If you have unstable angina, you may need to check into the hospital to get some rest, have more tests, and prevent complications.

First, your healthcare provider will need to find the blocked part or parts of the coronary arteries by performing a cardiac catheterization or coronary angiography. In this procedure, a catheter is guided through an artery in your arm or leg and into the coronary arteries, then injected with a liquid dye through the catheter. High-speed X-ray movies record the course of the dye as it flows through the arteries, and doctors can identify blockages by tracing the flow. An evaluation of how well your heart is working also can be done during cardiac catheterization.

Next, based on the extent of the coronary artery blockage(s) your doctor will discuss with you the following treatment options:

- Blood thinners (anticoagulants) are used to treat and prevent unstable angina. You will receive these drugs as soon as possible if you can take them safely.

- Antiplatelet agents include aspirin and the prescription drug clopidogrel or something similar (ticagrelor, prasugrel). These medicines may be able to reduce the chance of a heart attack or the severity of a heart attack that occurs. Dual therapy with aspirin and either clopidogrel (Plavix), prasugrel (Effient) and ticagrelor (Brilinta) decreases the risk of cardiovascular events in patients with acute coronary syndromes, acute myocardial infarction (heart attack), cardiovascular death, and stroke 12, 13.

- During an unstable angina event:

- You may get heparin (or another blood thinner) and nitroglycerin (under the tongue or through an IV). Anticoagulants (blood thinners) – reduce mortality by decreasing re-infarction rates in combination with antiplatelet agents. Used intravenously for acute treatment of unstable angina 12.

- Other treatments may include medicines to control blood pressure, anxiety, abnormal heart rhythms, and cholesterol (such as a statin drug).

- A procedure called percutaneous coronary intervention (coronary angioplasty) and stenting can often be done to open a blocked or narrowed coronary artery.

- Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) also called coronary angioplasty, is a nonsurgical but invasive procedure that improves blood flow to our heart. Doctors use percutaneous coronary intervention (coronary angioplasty) to open coronary arteries to the heart that are narrowed or blocked by plaque buildup. It is commonly used to open a blocked artery in patients suffering a heart attack due to a blocked coronary artery. Coronary angioplasty requires cardiac catheterization. A cardiologist, the doctor who specializes in the heart, performs percutaneous coronary intervention (coronary angioplasty) in a hospital cardiac catheterization laboratory. Live X-rays help your doctor guide a catheter through your blood vessels into your heart, where special contrast dye is injected to highlight any blockage. To open a blocked artery, your doctor will insert another catheter with a small inflatable balloon at the tip of that catheter over a guidewire. The balloon is inflated, squeezing open the fatty plaque deposit located on the inner lining of the coronary artery. Then the balloon is deflated and the catheter is withdrawn. Your doctor may also put a small mesh tube called a stent in your artery to help keep the artery open to allow for improved blood flow to the heart muscle. You may develop a bruise and soreness where the catheters were inserted. It also is common to have discomfort or bleeding where the catheters were inserted. You will recover in a special unit of the hospital for a few hours or overnight. You will get instructions on how much activity you can do and what medicines to take. You will need a ride home because of the medicines and anesthesia you received. Your doctor will check your progress during a follow-up visit. If a stent is implanted, you will have to take certain anticlotting medicines exactly as prescribed, usually for at least 3 to 12 months, but sometimes longer. Serious complications during or after a percutaneous coronary intervention (coronary angioplasty) procedure or as you are recovering after one are rare, but they can happen. This might include:

- Bleeding

- Blood vessel damage

- Treatable allergic reaction to the contrast dye

- Need for emergency coronary artery bypass grafting during the procedure

- Arrhythmias, or irregular heartbeats

- Kidney damage

- Heart attack

- Stroke

- Blood clots

- Sometimes chest pain can occur during percutaneous coronary intervention (coronary angioplasty) because the balloon briefly blocks blood supply to the heart. Restenosis, when tissue regrows where the artery was treated, may occur in the months after percutaneous coronary intervention (coronary angioplasty). This may cause the artery to become narrow or blocked again. The risk of complications from this procedure is higher if you are older, have chronic kidney disease, are experiencing heart failure at the time of the procedure, or have extensive heart disease and more than one blockage in your coronary arteries.

- A coronary artery stent is a small, metal mesh tube that opens up (expands) inside a coronary artery. A stent is often placed after coronary angioplasty. It helps prevent the artery from closing up again. The most common complication after a stenting procedure is a blockage or blood clot in the stent. A drug-eluting stent has medicine in it that helps prevent the artery from closing over time. You may need to take certain medicines, such as aspirin and other anti-clotting or anti-platelet medicines, for a year or longer after receiving a stent in an artery, to prevent serious complications such as blood clots.

- Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) also called coronary angioplasty, is a nonsurgical but invasive procedure that improves blood flow to our heart. Doctors use percutaneous coronary intervention (coronary angioplasty) to open coronary arteries to the heart that are narrowed or blocked by plaque buildup. It is commonly used to open a blocked artery in patients suffering a heart attack due to a blocked coronary artery. Coronary angioplasty requires cardiac catheterization. A cardiologist, the doctor who specializes in the heart, performs percutaneous coronary intervention (coronary angioplasty) in a hospital cardiac catheterization laboratory. Live X-rays help your doctor guide a catheter through your blood vessels into your heart, where special contrast dye is injected to highlight any blockage. To open a blocked artery, your doctor will insert another catheter with a small inflatable balloon at the tip of that catheter over a guidewire. The balloon is inflated, squeezing open the fatty plaque deposit located on the inner lining of the coronary artery. Then the balloon is deflated and the catheter is withdrawn. Your doctor may also put a small mesh tube called a stent in your artery to help keep the artery open to allow for improved blood flow to the heart muscle. You may develop a bruise and soreness where the catheters were inserted. It also is common to have discomfort or bleeding where the catheters were inserted. You will recover in a special unit of the hospital for a few hours or overnight. You will get instructions on how much activity you can do and what medicines to take. You will need a ride home because of the medicines and anesthesia you received. Your doctor will check your progress during a follow-up visit. If a stent is implanted, you will have to take certain anticlotting medicines exactly as prescribed, usually for at least 3 to 12 months, but sometimes longer. Serious complications during or after a percutaneous coronary intervention (coronary angioplasty) procedure or as you are recovering after one are rare, but they can happen. This might include:

- Coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG or bypass surgery) may be done for some people depending on the extent of coronary artery blockages and medical history. In this procedure, the surgeon creates new paths for blood to flow to the heart when the coronary arteries that supply blood to the heart itself are narrowed or blocked. The surgeon attaches a healthy piece of blood vessel from another part of the body on either side of a coronary artery blockage to bypass it. This surgery may lower the risk of serious complications for people who have obstructive coronary artery disease, which can cause chest pain or even heart failure. It may also be used in an emergency, such as a severe heart attack, to restore blood flow. Heart bypass surgery may be done for some people. The decision to have this surgery depends on:

- Which arteries are blocked

- How many arteries are involved

- Which parts of the coronary arteries are narrowed

- How severe the narrowings are

Variant angina or Prinzmetal’s angina

Variant angina also known as Prinzmetal’s angina, variant angina pectoris or vasospastic angina, is caused by spasm of the coronary artery that temporarily reduces blood flow to the heart muscles 14, 15. The coronary arteries may develop spasm as a result of exposure to cold weather, cold water, exercise, or a substance that promotes vasoconstriction as alpha-agonists (pseudoephedrine and oxymetazoline). Recreational drug use, for example, cocaine, amphetamines, alcohol, and marijuana use, is associated with the development of vasospastic angina, especially when used concurrently with cigarette smoking 16. Valsalva maneuver, hyperventilation, and coronary manipulation through cardiac catheterization also can produce hyperreactivity of the coronaries. Typical cardiovascular risk factors have not directly been associated with the presence of vasospastic angina, except for cigarette smoking and inflammatory states determined by high high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) levels 17. A metabolic disorder such as insulin resistance has also been associated with vasospastic angina 17.

Variant angina pectoris or Prinzmetal’s angina occurs almost only when you are at rest, with transient ischemic electrocardiographic changes in the ST segment, with a prompt response to nitrates 17. Severe chest pain is the main symptom of variant angina (Prinzmetal’s angina). Variant angina pectoris or Prinzmetal’s angina often doesn’t follow a period of physical exertion or emotional stress.

Variant angina pectoris or Prinzmetal’s angina is more common in women. Some studies show that the Japanese population has an increased risk of developing variant angina (Prinzmetal’s angina) when compared with Caucasian populations 18. The difference between the Japanese population and the Caucasian population is that the former has a three times higher risk. The average age of presentation of vasospastic angina is around the fifth decade of life. Females are more likely within the Japanese population to experience vasospastic angina 19.

Patients with vasospastic angina or Prinzmetal’s angina may present with the following:

- Variant angina pectoris or Prinzmetal’s angina can be very painful and usually occurs in cycles, typically at rest and overnight between midnight and 8 a.m.

- A chronic pattern of episodes of chest pain at rest that last 5 to 15 minutes, from midnight to early morning.

- Chest pain decreases with the use of short-acting nitrates.

- Typically, these patients have ischemic ST-segment changes on an electrocardiogram during an episode of chest discomfort, which returns to baseline on symptom resolution.

- Typically, the chest pain is not triggered by exertion or alleviated with rest as is typical angina.

- Often, the patient is younger with few or no classical cardiovascular risk factors.

Other vasospastic disorders, like Raynaud phenomenon or a migraine, can be associated with this subset of patients. Patients may complain of recent or past episodes with some symptom-free periods.

The international study group of coronary vasomotion disorders (COVADIS), created a diagnostic criterion to determine the presence of Prinzmetal angina. Vasospastic angina diagnostic criteria elements 20:

- Nitrate-responsive angina — during spontaneous episode, with at least one of the following:

- (a) Rest angina—especially between night and early morning

- (b) Marked diurnal variation in exercise tolerance—reduced in morning

- (c) Hyperventilation can precipitate an episode

- (d) Calcium channel blockers (but not β-blockers) suppress episodes

- Transient ischemic ECG charges — during spontaneous episode, including any of the following in at least two contiguous leads:

- (a) ST segment elevation ≥ 0.1 mV

- (b) ST segment depression ≥ 0.1 mV

- (c) New negative U waves

- Coronary artery spasm — defined as transient total or subtotal coronary artery occlusion (>90% constriction) with angina and ischemic ECG changes either spontaneously or in response to a provocative stimulus (typically acetylcholine ergot, or hyperventilation)

Footnotes:

- ‘Definitive vasospastic angina’ is diagnosed if nitrate-responsive angina is evident during spontaneous episodes and either transient ischemic ECG changes during the spontaneous episodes or coronary artery spasm criteria are fulfilled.

- ‘Suspected vasospasic angina’ is diagnosed if nitrate-responsive angina is evident during spontaneous episodes but transient ischemic ECG changes are equivocal or unavailable and coronary artery spasm criteria are equivocal.

Variant angina pectoris or Prinzmetal’s angina pain may be relieved by medicines such as calcium channel blockers. These medicines help dilate the coronary arteries and prevent spasm 17.

- Calcium channel blockers (calcium antagonists) play an important role in the management of vasospastic angina. It is a first-line treatment due to a vasodilation effect in the coronary vasculature. Calcium antagonist is effective in alleviating symptoms in 90% of patients. Moreover, one study demonstrated that the use of calcium channel blocker therapy was an independent predictor of myocardial infarct-free survival in vasospastic angina patients.

- The use of a long-acting calcium channel blocker (calcium antagonist) is recommended to be given at night as the episodes of vasospasm are more frequent at midnight and early in the morning. A high dose of long-acting calcium antagonists like diltiazem, amlodipine, nifedipine, or verapamil are recommended, and titration should be done on an individual basis with an adequate response and minimal side effects. In some cases, the use of a two-calcium antagonist (dihydropyridine and non-dihydropyridine) can be effective in patients with poor response to one agent.

- The use of long-acting nitrates are also effective in preventing vasospastic events, but chronic use is associated with tolerance. In patients on calcium antagonist without an adequate response to treatment, long-acting nitrates can be added.

- Nicorandil, a nitrate, and K-channel activator also suppress vasospastic attacks.

- The use of beta-blockers, especially those with nonselective adrenoceptor blocking effects, should be avoided because these drugs can aggravate the symptoms.

- Treatment with guanethidine, clonidine, or cilostazol has been reported to be beneficial in patients taking calcium channel antagonists. However, these drugs are not well-studied in this setting.

- The use of fluvastatin has been shown to be effective in preventing coronary spasm and may exert benefits via endothelial nitric oxide or direct effects on the vascular smooth muscle.

Microvascular angina

Microvascular angina also known as “cardiac syndrome X” or nonobstructive coronary heart disease, is more common in women particularly in perimenopausal and postmenopausal females 21, 22. Doctors have found that the pain of microvascular angina results from poor function of tiny blood vessels nourishing the heart (coronary microvascular disease), as well as the arms and legs. The prevalence of microvascular angina is estimated to be up to 30% of stable angina patients with non-obstructive coronary arteries 23. Classic microvascular angina is defined as a disease entity with (1) effort angina; (2) findings compatible with myocardial ischemia/coronary microvascular dysfunction upon diagnostic investigation; (3) the appearance of normal or near normal coronary arteries on angiography; and (4) absence of any other specific cardiac disease, such as variant angina, cardiomyopathy, or valvular disease 24. Findings compatible with myocardial ischemia include: (1) diagnostic ST segment depression during spontaneous or stress-induced typical chest pain; (2) reversible perfusion defects on stress myocardial scintigraphy; (3) documentation of stress-related coronary blood flow abnormalities using more advanced diagnostic techniques, such as cardiac magnetic resonance (MR), positron emission tomography (PET) or Doppler ultrasound; (4) metabolic evidence of transient myocardial ischemia (cardiac PET or MR, invasive assessment) 23.

The causes of microvascular angina aren’t fully known, although there different mechanisms and theories of the condition have been reported 25. These include problems with the inner lining of the small blood vessels, changes in the size and number of these vessels, problems with these vessels expanding to allow more blood to the heart during exercise or when you feel stressed or spasms within the walls of these very small arterial blood vessels causing reduced blood flow to the heart muscle. Another commonly hypothesized cause is heightened cardiac pain sensitivity, termed “hyperalgesia.” Microvascular angina is considered in patients with typical anginal chest pain and microvascular dysfunction of the coronary vessels after stressors such as exercise, which did not exhibit any evidence of ischemia of the myocardium by angiography 22. Patients with established microvascular angina often tend to have unfavorable cardiovascular events, leading to recurring hospitalizations, decreased quality of life, and poor prognostic outcomes. The challenge of achieving therapeutic efficacy from pharmacotherapy also poses additional barriers as traditional therapy for managing anginal chest pain is often unsuccessful. This often prolongs microvascular angina symptoms, prompts hospital admissions, restraining daily activities, and inability to attend work.

Subjects who have established microvascular angina have a 30% greater probability of presenting with underlying metabolic comorbid conditions when compared to the general population (8%). Potential contributing factors to the pathogenesis of microvascular angina and coronary microvascular dysfunction include insulin resistance and hyperglycemia, enhanced sodium-hydrogen exchange in red blood cells, chronic inflammation with elevated C-reactive protein levels (CRP), and vascular or nonvascular smooth muscle dysfunction 26.

Research shows that people with microvascular angina may be at increased risk of a heart attack or other heart problems. If you have been diagnosed with microvascular angina and you feel chest pain that does not go away after around 15 minutes, you should still call your local emergency services number immediately and ask for an ambulance.

Coronary microvascular disease sometimes called small artery disease or small vessel disease, is heart disease that affects the walls and inner lining of tiny coronary artery blood vessels that branch off from the larger coronary arteries 27. Coronary heart disease (coronary artery disease) involves plaque formation that can block blood flow to the heart muscle. In contrast, coronary microvascular disease, the heart’s coronary artery blood vessels don’t have plaque, but damage to the inner walls of the blood vessels can lead to spasms and decrease blood flow to the heart muscle. In addition, abnormalities in smaller arteries that branch off of the main coronary arteries may also contribute to coronary microvascular disease. People with microvascular angina have chest pain but have no apparent coronary artery blockages. Microvascular angina can be treated with some of the same medicines used for stable angina (angina pectoris).

Angina that occurs in coronary microvascular disease may differ from the typical angina that occurs in heart disease in that the chest pain usually lasts longer than 10 minutes, and it can last longer than 30 minutes. If you have been diagnosed with coronary microvascular disease, follow the directions from your healthcare provider regarding how to treat your symptoms and when to seek emergency assistance.

Microvascular angina chest pain or discomfort:

- May be more severe and last longer than other types of angina pain

- May occur with shortness of breath, sleep problems, fatigue, and lack of energy

- Often people who experience coronary microvascular disease symptoms often first notice them during their routine daily activities and times of mental stress. They occur less often during physical activity or exertion. This differs from disease of the major coronary arteries and main branches, in which symptoms usually first appear during physical activity.

The risk factors for coronary microvascular disease are the same as for coronary artery disease, including diabetes, high blood pressure and high cholesterol.

Many researchers think some of the risk factors that cause atherosclerosis may also lead to coronary microvascular disease. Atherosclerosis is a disease in which plaque builds up inside the arteries. Risk factors for atherosclerosis include:

- Unhealthy blood cholesterol levels

- High blood pressure

- Smoking

- Diabetes

- Overweight and obesity

- Lack of physical activity

- Unhealthy diet

- Older age

- Family history of heart disease

No studies have been done on how to prevent coronary microvascular disease. Researchers don’t yet know how or in what way preventing coronary microvascular disease differs from preventing heart disease.

Knowing your family history of heart disease, making the following lifestyle changes and ongoing care can help you lower your risk for heart disease.

- Manage blood pressure

- Control cholesterol

- Reduce blood sugar

- Get active

- Eat better

- Lose or manage weight

- Stop smoking

Microvascular angina is primarily a diagnosis of occlusion, which further prompts extensive workup and assessment that can be costly and time-consuming 25. Patients present with typical or atypical anginal chest pain, ST depression, and no evidence of coronary vessel obstruction greater than 50% on angiography 25.

Research to identify better ways to detect and diagnose coronary microvascular disease is ongoing. Diagnosing coronary microvascular disease was previously a challenge. Standard tests for coronary artery disease may not be able to detect coronary coronary microvascular disease. These tests look for blockages in the large coronary arteries. Coronary microvascular disease affects the tiny coronary arteries. If you have angina but tests show your coronary arteries are normal, you could still have coronary microvascular disease. PET scans and MRI imaging are now available which measure blood flow through the coronary arteries and can detect coronary coronary microvascular disease in very small blood vessels.

Newer tests to assess small vessel function in the heart include:

- Using small guidewires, about the thickness of a human hair, passed into a coronary artery during an angiogram in order to measure blood vessel function.

- A test using a drug called acetylcholine.

The Coronary Vasomotion Disorders International Study (COVADIS) Group define microvascular angina as symptoms of myocardial ischemia with proven coronary microvascular dysfunction (e.g. index of microcirculatory resistance (IMR) ≥25, coronary flow reserve (CFR) <2.0 or abnormal microvascular constriction during acetylcholine infusion), with unobstructed epicardial coronary arteries 28.

Microvascular angina clinical diagnostic criteria 29:

- Symptoms of myocardial ischemia

- a) Effort and/or rest angina

- b) Angina equivalents (i.e. shortness of breath)

- Absence of obstructive coronary artery disease (<50% diameter reduction and/or Fractional Flow Reserve [FFR] by >0.80) by

- a) Coronary CT angiography

- b) Invasive coronary angiography

- Objective evidence of myocardial ischemia

- a) Ischemic ECG changes during an episode of chest pain

- b) Stress-induced chest pain and/or ischemic ECG changes in the presence or absence of transient/reversible abnormal myocardial perfusion and/or wall motion abnormality

- Evidence of impaired coronary microvascular function

- a) Impaired coronary flow reserve (cut-off values depending on methodology use between ≤2.0 and ≤2.5)

- b) Abnormal coronary microvascular resistance indices (e.g. index of microvascular resistance (IMR) > 25) 30

- c) Coronary microvascular spasm, defined as reproduction of symptoms, ischemic ECG shifts but no epicardial spasm during acetylcholine testing.

- d) Coronary slow flow phenomenon, defined as TIMI frame count (TFC) >25.

Additional testing can confirm the diagnosis.

Coronary microvascular disease symptoms often first occur during routine daily tasks. Because of this, you may be asked to fill out a questionnaire called the Duke Activity Status Index (DASI). The Duke Activity Status Index (DASI) is a patient-reported estimate of functional capacity, maximal oxygen consumption (VO2 max) and maximum metabolic equivalent of tasks (METs) 31. The Duke Activity Status Index (DASI) includes questions about how well you’re able to do daily activities, such as shopping, cooking and going to work. The Duke Activity Status Index (DASI) results can help determine what additional tests are needed to make the diagnosis of coronary microvascular disease 32.

The Duke Activity Status Index (DASI) is a self-administered questionnaire that measures a person’s functional capacity. The Duke Activity Status Index (DASI) questionnaire produces a score between 0 and 58.2 points, which is linearly correlated with a patient’s maximal oxygen consumption (VO2 max) and maximum metabolic equivalent of tasks (METs), as measured from cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET).

The Duke Activity Status Index Questionnaire 31:

- Can you take care of yourself (eating, dressing, bathing or using the toilet)?

- Yes (+ 2.75)

- No (+ 0.0)

- Can you walk indoors, such as around your house?

- Yes (+ 1.75)

- No (+ 0.0)

- Can you walk a block or two on level ground?

- Yes (+ 2.75)

- No (+ 0.0)

- Can you climb a flight of stairs or walk up a hill?

- Yes (+ 5.50)

- No (+ 0.0)

- Can you run a short distance?

- Yes (+ 8.0)

- No (+ 0.0)

- Can you do light work around the house, such as dusting or washing dishes?

- Yes (+ 2.75)

- No (+ 0.0)

- Can you do moderate work around the house, such as vacuuming, sweeping floors or carrying in groceries?

- Yes (+ 3.0)

- No (+ 0.0)

- Can you do heavy work around the house, such as scrubbing floors or lifting and moving heavy furniture?

- Yes (+ 8.0)

- No (+ 0.0)

- Can you do yard work, such as raking leaves, weeding or pushing a power mower?

- Yes (+ 4.5)

- No (+ 0.0)

- Can you have sexual relations?

- Yes (+ 5.25)

- No (+ 0.0)

- Can you participate in moderate recreational activities, such as golf, bowling, dancing, doubles tennis or throwing a baseball or football?

- Yes (+ 6.0)

- No (+ 0.0)

- Can you participate in strenuous sports, such as swimming, singles tennis, football, basketball or skiing?

- Yes (+ 7.50)

- No (+ 0.0)

Duke Activity Status Index (DASI) = sum of “Yes” replies ___________ (the higher the score (maximum 58.2), the higher the functional status.)

VO2max (in mL/kg/min) = (0.43 x DASI) + 9.6

VO2max = ___________ ml/kg/min ÷ 3.5 ml/kg/min = __________ METS (maximum metabolic equivalent of tasks)

The management of patients suspected of having microvascular angina is challenging and complex as its cause is not entirely understood. To date, there are no specific guidelines to treat microvascular angina, and management should be initiated on a case by case basis.

Treatment of coronary microvascular disease involves pain relief, controlling risk factors and other symptoms.

Microvascular angina treatments may include medicines such as:

- Cholesterol medication to improve cholesterol levels.

- Blood pressure medications to lower high blood pressure and decrease the heart’s workload.

- Antiplatelet medication to help prevent blood clots.

- Medications to relax blood vessels including beta blockers, calcium channel blockers and nitroglycerin.

- Nitroglycerin to treat chest pain.

Pharmacologic management of microvascular angina can be initiated by conventional anti-ischemic agents such as beta-blockers, nitrates, and calcium channel blockers. Additional agents like angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, statins, and antianginals such as ranolazine may also be used. Calcium channel blockers (nifedipine, verapamil, diltiazem) may be an alternative therapy to beta-blockers if a therapeutic response is not achieved 33. Although calcium channel blockers increase exercise tolerance and minimize the episodes of angina, they are reported to be not as effective as beta-blockers in patients with microvascular angina. Ranolazine, a recent antianginal indicated for chronic angina used in patients with refractory angina, has also been reported to be an effective alternative for therapy. Ranolazine’s function to regulate neuronal voltage-gated sodium channels plays a role in managing potential neuropathic pain in patients with microvascular angina. A Seattle Angina Questionnaire reported ranolazine as a beneficial agent in females with anginal symptoms and no reported evidence of coronary artery obstruction 34.

Statins enhance the endothelium’s vasodilatory effects and may be effective in patients with microvascular angina. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors have also been reported to be beneficial. They impede endothelial bradykinin degradation, which results in vasodilatory effects 33. These effects may further regulate the microvascular tone of the coronary vessels.

Based on the hypothesis of altered pain perception in patients with microvascular angina, analgesic pharmacotherapy may be effective. Pain management with agents like tricyclic antidepressants (TCA), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and xanthine derivatives (adenosine receptor blockers) have been reported to show effectiveness.

Agents such as xanthine derivatives (adenosine receptor blockers), aminophylline, and imipramine have been proposed in select patients. Imipramine has been reported to decrease the frequency of chest pain by roughly 50% 25. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) action of serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibition exerts analgesic action; hence their proposed benefits in patients with microvascular angina. Imipramine is also advised by the American College of Cardiology for microvascular angina patients unresponsive to beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, and nitrates. Imipramine, used in the management of microvascular angina, has been controversial due to its adverse effects.

Lifestyle changes or improvements are also recommended, other treatment modalities such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and neural electrical stimulation may be considered in select patients 35. Neural electrical stimulation procedures target increased pain sensitivity in microvascular angina and are utilized in subjects resistant to pharmacotherapy. Procedures include spinal cord stimulation and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS). The therapeutic effects reportedly enhance parasympathetic activity, further improving endothelial dysfunction and pain sensitivity. Other reported actions include increasing blood flow in the coronary vessels by spinal cord stimulation.

The intensity of microvascular angina symptoms is reported to reduce in 30% of subjects but may progressively worsen in approximately 20% of patients over time 36, 22. A study conducted on a cohort of female subjects reported 45% of individuals with chest pain and no evidence of coronary artery obstruction by imaging (angiography) reported ongoing typical or atypical chest pain persisting greater than 12 months. The study also reported subjects to have twice the risk for adverse cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction [heart attack], stroke, heart failure, and cardiovascular mortality).

Progressive disease comprises regular and lengthy anginal chest pains that manifest at decreased exertion levels and may even occur at rest. Some subjects may also experience a disease course resistant to pharmacological management, which further diminishes the quality of life. Patients with a progressive disease course may require drastic diagnostics that could lead to functional disability 22.

What’s the difference between angina and a heart attack?

It can be very difficult to tell if your chest pain or symptoms are angina or if they are due to a heart attack, as the symptoms can be similar. If it’s angina, your symptoms usually ease or go away after a few minutes’ rest, or after taking the medicines your doctor has prescribed for you, such as nitrates. A heart attack happens when blood flow to the heart suddenly becomes blocked. Without the blood coming in, the heart can’t get oxygen. If not treated quickly, the heart muscle begins to die. Most heart attacks happen when a blood clot suddenly cuts off the hearts’ blood supply, causing permanent heart damage. The most common cause of heart attacks is coronary artery disease (coronary heart disease). A less common cause of heart attack is a severe spasm (tightening) of a coronary artery. The spasm cuts off blood flow through the coronary artery. If you’re having a heart attack, your symptoms are less likely to ease or go away after resting or taking medicines.

At the hospital, doctors make a diagnosis of angina or a heart attack based on your symptoms, blood tests, and different heart health tests. Treatments may include medicines and medical procedures such as coronary angioplasty. After a heart attack, cardiac rehabilitation and lifestyle changes can help you recover.

Why does coronary heart disease affect women differently?

Hormonal changes affect a woman’s risk for coronary heart disease. Before menopause, the hormone estrogen provides women with some protection against coronary artery disease. Estrogen raises levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol (sometimes called “good” cholesterol) and helps keep the arteries flexible so they can widen to deliver more oxygen to the tissues of the heart in response to chemical and electrical signals. After menopause, estrogen levels drop, increasing a woman’s risk for coronary heart disease.

The size and structure of the heart is different for women and men. A woman’s heart and blood vessels are smaller, and the muscular walls of women’s hearts are thinner.

Women are also more likely to have heart disease in the smaller arteries of their heart, called coronary microvascular disease. This can make it harder to diagnose and cause delays in treatment.

Coronary artery disease symptoms

Coronary artery disease (coronary heart disease) signs and symptoms occur when your heart doesn’t get enough oxygen-rich blood. If you have coronary artery disease, reduced blood flow to your heart can cause chest pain (angina) and shortness of breath. A complete blockage of blood flow can cause a heart attack. Furthermore, coronary artery disease (coronary heart disease) symptoms can be different for everyone and some people don’t know they have coronary heart disease before they have a heart attack.

Coronary artery disease (coronary heart disease) often develops over decades. Symptoms may go unnoticed until a significant blockage causes problems or a heart attack occurs.

At first your symptoms may go unrecognized or they may only occur when your heart is beating hard like during exercise. As the coronary arteries continue to narrow, less and less blood gets to the heart and symptoms can become more severe or frequent.

Coronary artery disease (coronary heart disease) signs and symptoms can include:

- Chest pain (angina). You may feel pressure or tightness in your chest. Some people say it feels like someone is standing on their chest. The chest pain usually occurs on the middle or left side of the chest. Activity or strong emotions can trigger angina. The pain usually goes away within minutes after the triggering event ends. In some people, especially women, the pain may be brief or sharp and felt in the neck, arm or back.

- Shortness of breath. You may feel like you can’t catch your breath.

- Fatigue. If the heart can’t pump enough blood to meet your body’s needs, you may feel unusually tired.

- Feeling pain throughout your body

- Feeling faint

- Feeling sick (nausea)

- Sweating

- Heart attack. A completely blocked coronary artery will cause a heart attack. The classic signs and symptoms of a heart attack include crushing chest pain or pressure, shoulder or arm pain, shortness of breath, and sweating. Women may have less typical symptoms, such as neck or jaw pain, nausea and fatigue. Some heart attacks don’t cause any noticeable signs or symptoms.

But not everyone has the same symptoms and some people may not have any before coronary heart disease is diagnosed.

Heart Attack Warning Signs

Coronary heart disease raises your risk for a heart attack. Learn the signs and symptoms of a heart attack, and call your local emergency number if you have any of these symptoms:

- Chest pain or discomfort. This involves uncomfortable pressure, squeezing, fullness, or pain in the center or left side of the chest that can be mild or strong. This pain or discomfort often lasts more than a few minutes or goes away and comes back.

- Upper body discomfort in one or both arms, the back, neck, jaw, or upper part of the stomach.

- Shortness of breath, which may occur with or before chest discomfort.

- Nausea (feeling sick to your stomach), vomiting, light-headedness or fainting, or breaking out in a cold sweat.

Symptoms also may include sleep problems, fatigue (tiredness), and lack of energy.

The symptoms of angina can be similar to the symptoms of a heart attack. Angina pain usually lasts for only a few minutes and goes away with rest.

Chest pain or discomfort that doesn’t go away or changes from its usual pattern (for example, occurs more often or while you’re resting) can be a sign of a heart attack. If you don’t know whether your chest pain is angina or a heart attack, call your local emergency number.

Let the people you see regularly know you’re at risk for a heart attack. They can seek emergency care for you if you suddenly faint, collapse, or have other severe symptoms.

Coronary artery disease complications

Coronary artery disease can cause serious complications. Coronary artery disease can lead to:

- Chest pain (angina). When the coronary arteries narrow, the heart may not get enough blood when it needs it most — like when exercising. This can cause chest pain (angina) or shortness of breath.

- Heart attack. A heart attack can happen if a cholesterol plaque breaks open and causes a blood clot to form. A clot can block blood flow. The lack of blood can damage the heart muscle. The amount of damage depends in part on how quickly you are treated.

- Heart failure. Narrowed arteries in the heart or high blood pressure can slowly make the heart weak or stiff so it’s harder to pump blood. Heart failure is when the heart doesn’t pump blood as it should.

- Irregular heart rhythms (arrhythmias). Not enough blood to the heart can alter normal heart signaling, causing irregular heartbeats.

- Dying suddenly from heart problems.

Arrhythmias, acute coronary syndrome, congestive heart failure, mitral regurgitation, ventricular free wall rupture, pericarditis, aneurysm formation, and mural thrombi are the main complication associated with coronary artery disease 37, 38.

Coronary artery disease causes

Scientists think coronary artery disease starts when the very inner lining of the coronary artery (the endothelium) is damaged. High blood pressure, high levels of cholesterol and triglycerides in the blood, and smoking are believed to lead to the development of plaque (atheroma). This process is called atherosclerosis. Plaque can cause the arteries to narrow, blocking blood flow. If a piece of atheroma (plaque) breaks off, it can cause a blood clot form. This clot can block your coronary artery and cut off the supply of blood and oxygen to your heart muscle. This is known as a heart attack. Small amounts of plaque can also develop in the small blood vessels in the heart, causing coronary microvascular disease.

Besides high cholesterol, damage to the coronary arteries may be caused by:

- Diabetes or insulin resistance

- High blood pressure

- Not getting enough exercise (sedentary lifestyle)

- Smoking or tobacco use

Problems with how the heart’s blood vessels work can cause of coronary heart disease. For example, the blood vessels may not respond to signals that the heart needs more oxygen-rich blood. Normally, the blood vessels widen to allow more blood flow when a person is physically active or under stress. If you have coronary heart disease, the size of these blood vessels may not change, or the blood vessels may even narrow.

The cause of these problems is not fully clear. But it may involve damage or injury to the walls of the arteries or tiny blood vessels from chronic inflammation, high blood pressure, or diabetes, all of which can cause blood vessels to narrow over time.

Damage to the inner walls of the larger coronary arteries can cause them to spasm (suddenly tighten). This is called vasospasm. The spasm causes the arteries to narrow temporarily and blocks blood flow to the heart.

Coronary artery disease risk factors

A risk factor is something about you that increases your chance of getting a disease or having a certain health condition.

Coronary artery disease risk factors include:

- Your age. Risk of heart disease increases with age. In the diagnostic and interventional cardiac catheterization registry by the French Society of Cardiology (ONACI), the incidence of coronary artery disease was about 1% in the 45 to 65 age group, which increased to about 4% as the age group reached 75 to 84 years 39.

- Your sex. Coronary heart disease affects men and women. Men have a higher risk of getting heart disease than women who are still menstruating. After menopause, the risk for women gets closer to the risk for men. Microvascular angina most often begins in women around the time of menopause. Since microvascular angina is harder to diagnose, women may not be diagnosed and treated as quickly as men. If you are a woman having chest discomfort or shortness of breath during physical activity, ask your doctor about tests to check for non-obstructive coronary artery disease or coronary microvascular disease.

- Your genes or race. If your parents had heart disease, you are at higher risk. African Americans, Mexican Americans, American Indians, Hawaiians, and some Asian Americans also have a higher risk for heart problems. For Hispanics, Asian Americans or Pacific Islanders, and American Indians or Alaska Natives, heart disease is second only to cancer. People of South Asian ancestry are at higher risk of developing coronary heart disease and serious complications than other Asian Americans. Research shows that some genes are linked with a higher risk for coronary heart disease.

- Family history. A family history of heart disease makes you more likely to get coronary artery disease. This is especially true if a close relative (parent, sibling) developed heart disease at an early age. The risk is highest if your father or a brother had heart disease before age 55 or if your mother or a sister developed it before age 65.

- Tobacco use. Smoking, chewing tobacco and long-term exposure to secondhand smoke can damage the lining of the arteries, allowing deposits of cholesterol to collect and block blood flow. If you smoke, quit.

- High blood pressure. Uncontrolled high blood pressure can make arteries hard and stiff (arterial stiffness). The coronary arteries may become narrow, slowing blood flow. You can control high blood pressure through diet, exercise, and medicines, if needed.

- High cholesterol. Too much bad cholesterol in the blood can increase the risk of atherosclerosis. Bad cholesterol is called low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and triglycerides. Not enough good cholesterol — called high-density lipoprotein (HDL) — also leads to atherosclerosis. You can control your cholesterol through diet, exercise, and medicines.

- Diabetes. Diabetes increases the risk of coronary artery disease. Type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease share some risk factors, such as obesity and high blood pressure. You can control diabetes through diet, exercise, and medicines, if needed.

- Overweight or obesity. Excess body weight is bad for overall health. Obesity can lead to type 2 diabetes and high blood pressure. Keeping to a healthy weight by eating healthy foods, eating less, and joining a weight loss program, if you need to lose weight. Ask your health care provider what a healthy weight is for you.

- Other medical conditions. There are also several medical conditions that are not directly related to your heart and blood vessels that may increase your risk for coronary heart disease, such as:

- Autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, such as Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, psoriasis, lichen planus, pemphigus, histiocytosis, lupus erythematosus, and rheumatoid arthritis.

- Chronic kidney disease. Having long-term kidney disease increases the risk of coronary artery disease.

- Diabetes.

- HIV/AIDS, especially among older adults. Part of the risk might be due to side effects of HIV treatments.

- Mental health conditions, including anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

- Metabolic syndrome.

- Sleep disorders, such as sleep apnea or sleep deprivation and deficiency

- Not getting enough exercise. Physical activity is important for good health. A lack of exercise (sedentary lifestyle) is linked to coronary artery disease and some of its risk factors. Try to exercise at least 30 minutes a day.

- A lot of stress. Emotional stress may damage the arteries and worsen other risk factors for coronary artery disease. Learn healthy ways to cope with stress through special classes or programs, or things like meditation or yoga.

- Unhealthy diet. Eating foods with a lot of saturated fat, trans fat, salt and sugar can increase the risk of coronary artery disease.

- Alcohol use. Heavy alcohol use can lead to heart muscle damage. It can also worsen other risk factors of coronary artery disease. Limit how much alcohol you drink to 1 drink a day for women and 2 a day for men.

- Amount of sleep. Too little and too much sleep have both been linked to an increased risk of heart disease.

- Environment and occupation factors. Air pollution in the environment can put you at higher risk of coronary heart disease. The increase in risk may be higher in older adults, women, and people who have diabetes or obesity. Air pollution may cause or worsen other conditions that are known to increase your risk of coronary heart disease, such as atherosclerosis and high blood pressure. Your work can raise your risk if you:

- Are exposed to toxins, radiation, or other hazards

- Have a lot of stress at work

- Sit for long periods

- Work more than 55 hours a week, or work long, irregular, or night shifts that affect your sleep

Risk factors often occur together. One risk factor may trigger another. When grouped together, certain risk factors make you even more likely to develop coronary artery disease. For example, metabolic syndrome — a cluster of conditions that includes high blood pressure, high blood sugar, excess body fat around the waist and high triglyceride levels — increases the risk of coronary artery disease.

Sometimes coronary artery disease develops without any classic risk factors.

Other possible risk factors for coronary artery disease may include:

- Breathing pauses during sleep (obstructive sleep apnea). Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) causes breathing to stop and start during sleep. It can cause sudden drops in blood oxygen levels. The heart must work harder. Blood pressure goes up.

- High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP). High-sensitivity C-reactive (hs-CRP) protein appears in higher-than-usual amounts when there’s inflammation somewhere in the body. High hs-CRP levels may be a risk factor for heart disease. It’s thought that as coronary arteries narrow, the level of hs-CRP in the blood goes up.

- High triglycerides. This is a type of fat (lipid) in the blood. High levels may raise the risk of coronary artery disease, especially for women.

- Homocysteine. Homocysteine is an amino acid the body uses to make protein and to build and maintain tissue. But high levels of homocysteine may increase the risk of coronary artery disease.

- Preeclampsia. This pregnancy complication causes high blood pressure and increased protein in the urine. It can lead to a higher risk of heart disease later in life.

- Other pregnancy complications. Diabetes or high blood pressure during pregnancy are also known risk factors for coronary artery disease.

- Certain autoimmune diseases. People who have conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and lupus (and other inflammatory conditions) have an increased risk of atherosclerosis.

Coronary artery disease prevention

The same lifestyle habits used to help treat coronary artery disease can also help prevent it. Good nutrition is important to your heart health and will help control some of your risk factors.

To improve heart health, follow these tips:

- Choose a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains.

- Choose lean proteins, such as chicken, fish, beans and legumes.

- Choose low-fat dairy products, such as 1% milk and other low-fat items.

- Avoid sodium (salt) and fats found in fried foods, processed foods, and baked goods.

- Eat fewer animal products that contain cheese, cream, or eggs.

- Read labels, and stay away from “saturated fat” and anything that contains “partially-hydrogenated” or “hydrogenated” fats. These products are usually loaded with unhealthy fats.

- Quit smoking.

- Control high blood pressure, high cholesterol and diabetes.

- Exercise often.

- Maintain a healthy weight.

- Reduce and manage stress.

Follow these guidelines and the advice of your health care provider to lower your chances of developing coronary heart disease.

Coronary artery disease diagnosis

Your doctor will be able to tell whether you have coronary heart disease if you’re experiencing symptoms of angina. To help diagnose coronary artery disease, your doctor will talk to you about your symptoms and examine you. You’ll also be asked about any risk factors, including whether you have a family history of heart disease. Blood tests are usually done to check your overall health.

Tests used to diagnose and confirm coronary artery disease include:

- Electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG). Electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG) is a quick and painless test that measures the electrical activity of the heart. Sticky patches (electrodes) are placed on the chest and sometimes the arms and legs. Wires connect the electrodes to a computer, which displays the test results. An ECG can show if the heart is beating too fast, too slow or not at all. Your health care provider also can look for patterns in the heart rhythm to see if blood flow through the heart has been slowed or interrupted.

- Hyperventilation testing. Hyperventilation testing can help diagnose variant angina. Rapid breathing under controlled conditions with careful medical monitoring may bring on electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG) changes that help your doctor diagnose variant angina.

- A blood test called troponin that measures damage to the heart muscle. Troponin is a protein found in the muscles of the heart. Normally, troponin levels are close to undetectable in the blood. When heart muscles are injured or damaged, troponin is released into the bloodstream and, as heart damage progresses, greater amounts of troponin may be detected. Doctors commonly test troponin levels several times over a 24-hour period when a person is suspected of having had a heart attack. Testing may also be ordered to evaluate heart injury related to certain medical procedures. A troponin test requires a blood sample and is typically performed in an emergency room, hospital, or similar medical setting.

- Chest X-ray. A chest X-ray shows the condition of the heart and lungs. A chest X-ray may be done to determine if other conditions are causing chest pain symptoms and to see if the heart is enlarged.

- Exercise stress test, which measures blood pressure and heart activity during exercise. Sometimes angina is easier to diagnose when the heart is working harder. A stress test typically involves walking on a treadmill or riding a stationary bike while the heart is monitored. Other tests may be done at the same time as a stress test. If you can’t exercise, you may be given drugs that mimic the effect of exercise on the heart.

- Nuclear stress test also known as a radionuclide scan, myocardial perfusion scintigraphy, myoview or thallium scan. A nuclear stress test helps measure blood flow to the heart muscle at rest and during stress. It can show the blood flow to your heart and how your heart functions when it has to work harder – for example, when you’re active. You will be given an injection of a small amount of isotope (a radioactive substance). A large camera is then put in position close to your chest and takes pictures of your heart. These pictures help your doctor to work out if the problem is angina, how much it is affecting the heart, and what treatment would be most helpful.

- Echocardiogram or echo, which uses sound waves to create images of your heart in motion. These images can show how blood flows through the heart. An echocardiogram may be done during a stress test, where it’s called stress echocardiogram. A stress echocardiogram is when the echocardiogram is recorded after the heart has been put under stress – either during exercise or after giving you a particular type of medicine that speeds up the heart to mimic exercise. The test can show if any areas of your heart are getting less blood flow when your heart is working hard. The stress echocardiogram pictures help your doctor to work out if the problem is angina, and how much it is affecting the heart. Your doctor can then decide what treatment might be most helpful.

- Coronary angiography. Coronary angiogram uses X-ray imaging to examine the inside of the heart’s blood vessels. It’s part of a general group of procedures known as cardiac catheterization. A health care provider threads a thin tube (catheter) through a blood vessel in your arm or groin to an artery in your heart and injects dye through the catheter. The dye makes the heart arteries show up more clearly on an X-ray. The dye helps blood vessels show up better on the images and outlines any blockages. Your health care provider might call this type of X-ray an angiogram. If you have an artery blockage that needs treatment, a balloon on the tip of the catheter can be inflated to open the artery. A mesh tube (stent) is typically used to keep the artery open.

- Cardiac computerized tomography (coronary CT). For this test, you typically lie on a table inside a doughnut-shaped machine. An X-ray tube inside the machine rotates around the body and collects images of the heart and chest. A cardiac CT scan can show if the heart is enlarged or if any heart’s arteries are narrowed. Coronary CT can show the blood flow through your coronary arteries and will give you a ‘calcium score’, which is a measure of how much calcium there is in the artery walls. The higher your calcium score is, the higher your risk of having

coronary heart disease. - Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). This test uses magnetic fields and radio waves to create detailed images of the heart. You typically lie on a table inside a long, tubelike machine that produces detailed images of the heart’s structure and blood vessels.

- Cardiac positron emission tomography (PET) scanning assesses blood flow through the small coronary blood vessels and into the heart tissues. This is a type of nuclear heart scan that can diagnose coronary microvascular disease.

Coronary artery disease treatment

Your treatment for coronary artery disease depends on how serious your symptoms are and any other health conditions you have. If you are experiencing a heart attack, for example, you may need emergency treatment. If your healthcare provider diagnoses you with coronary heart disease based on symptoms and tests, your treatment may include heart-healthy lifestyle changes (such as not smoking, eating healthy and exercising more) in combination with medications to prevent a heart attack or other health problems. Your doctor will consider your 10-year risk calculation when deciding how best to treat your coronary heart disease. For example, the Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Estimator (https://tools.acc.org/ASCVD-Risk-Estimator-Plus/#!/calculate/estimate/) considers your cholesterol levels, age, sex, race, and blood pressure. The Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Estimator (ASCVD Risk Estimator Plus) also factors in whether you smoke or take medicines to manage your high blood pressure or cholesterol. However, no single risk calculator is appropriate for all people. Calculators can give you and your doctor a good idea about your risk, but your doctor may consider other factors to estimate your risk more accurately.

Commonly used risk calculators might not accurately estimate risk in certain situations:

- Risk calculators may not account for complications during pregnancy or had early menopause.

- People with metabolic syndrome or an inflammatory or autoimmune condition also need to be aware that common risk calculators may not factor in their condition.

- Family history of heart or blood vessel disease at a young age may also cause an inaccurate estimate.

- People who use statins to manage cholesterol levels will also get an inaccurate estimate of risk from these calculators.

In these cases, your healthcare provider may suggest other tests for coronary heart disease even if the Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Estimator (ASCVD Risk Estimator Plus) or other calculator says you are not at high risk.

Ask about your risk during your annual check-up. Knowing your risk will help you and your provider decide on healthy lifestyle changes and possibly medicines to lower your risk.

Risk assessments should be repeated every 4 to 6 years in adults 20 to 79 years of age who do not have heart or blood vessel disease.

Heart-Healthy Lifestyle Changes