Contents

- Rubella

- What cause rubella?

- Rubella prevention

- Rubella vaccine

- Rubella in pregnancy

- Congenital rubella syndrome

- Rubella symptoms

- Rubella complications

- Rubella diagnosis

- Rubella treatment

- Rubella prognosis

Rubella

Rubella also called “German measles” or “3-day measles” is an infection caused by the Rubella virus 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. Rubella is usually mild with fever and a rash. It typically begins with low-grade fever, a general feeling of being unwell (malaise) and swollen lymph nodes (lymphadenopathy), followed by a brief generalized erythematous maculopapular rash 2, 3. About half of the people who get rubella do not have symptoms. If you do get them, symptoms may include:

- A rash that starts on the face and spreads to the body

- Mild fever

- Aching joints, especially in young women

- Swollen glands. Swollen glands caused by rubella are usually found at the back of your neck and behind your ears

Rubella spreads when an infected person coughs or sneezes and usually causes a rash that first appears on the face. People without symptoms can still spread rubella. A person with rubella may spread the disease to others up to 1 week before the rash appears; they can remain contagious up to 7 days after. About 25 to 50% of people infected with rubella will not develop a rash or experience any symptoms, but they can still spread the infection to others.

Rubella is usually not dangerous. However, rubella is very dangerous during pregnancy and for a pregnant woman’s baby. Rubella can cause miscarriage, stillbirth or birth defects. And babies of mothers who catch rubella during pregnancy, can be seriously affected by congenital rubella syndrome.

Although rubella was declared eliminated from the United States in 2004, cases can occur when unvaccinated people are exposed to infected people. This mostly happens through international travel. Rubella can be prevented with measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine.

You should see your doctor if you think you or your child may have rubella. It is important to get a diagnosis from a doctor, as many other illnesses have symptoms like rubella. Your doctor will ask you about your symptoms and examine your rash. Your doctor may also ask if you think you have had contact with anyone who has rubella. Your doctor will ask you about your vaccination history.

If your doctor suspects that you may have rubella, he/she may refer you for a blood test to confirm the diagnosis. They may also refer you for other tests to rule out illnesses with similar symptoms.

There is no specific medicine to treat rubella or make the disease go away faster. In many cases, symptoms are mild. Most people recover from rubella by themselves without medical treatment. For others, mild symptoms can be managed with bed rest and medicines for fever, such as acetaminophen (paracetamol). If you are concerned about your symptoms or your child’s symptoms, contact your doctor.

Figure 1. Rubella

Figure 2. Forchheimer spots (petechiae on the soft palate)

Footnotes: Petechiae on the soft palate (Forchheimer spots) can also be observed in approximately 20% of the patients. Forchheimer spots are not specific to rubella and can be seen in cases of measles, scarlet fever, and other systemic infections 6. However, in combination with clinical information, the presence of Forchheimer spots supports a diagnosis of rubella.

[Source 7 ]What cause rubella?

Rubella also known as “German measles” or “3-day measles” is an infection caused by the Rubella virus. Rubella virus is a positive sense, single-stranded RNA virus acquired via inhalation of infectious large particle aerosols during close and prolonged contact with infected individuals 4, 5. Humans are the only known reservoir for rubella. Rubella virus initially replicates in the nasopharyngeal cells and regional lymph nodes. Viremia occurs 5 to 7 days after inoculation, allowing the infection to spread throughout the body. Rubella virus is sensitive to heat (temperature >56°C), ultraviolet light, and extremes of pH (pH <6.8 or >8.1) 2.

The Rubella virus genome encodes five proteins, two non-structural proteins (p90 and p150) and three structural proteins (two glycoproteins [E1 and E2] and the capsid protein [CP]) 8. The E1 glycoprotein contains the antigenic determinants that induce major immune responses through hemagglutination-neutralizing epitopes and is responsible for receptor-mediated endocytosis 9, 10, 11, 12. A single serotype of the wild-type Rubella virus and several genotypes circulate globally 13.

Rubella virus spreads when an infected person coughs or sneezes. Rubella can also be spread by person-to person contact. A person with rubella can infect others (be contagious) from 1 week before the rash appears; they can remain contagious up to 7 days after. However, 25% to 50% of people with rubella do not develop any symptoms but they can still spread it to others.

If you are pregnant and infected with rubella, you can pass the rubella virus to your developing baby which cause serious harm. This may cause congenital rubella syndrome.

Rubella remains a problem in other parts of the world. It can still be brought into the United States by people who get infected in other countries. The new Global Vaccine Action Plan has goals of establishing regional elimination of measles and rubella in at least five WHO regions by 2020 14. In 2015, the World Health Organization Region of the Americas became the first in the world to be declared free of endemic rubella virus transmission. Rubella virus continues to circulate widely, especially in Africa, East Asia, and South Asia; ≈49,000 cases were reported worldwide in 2019, and ≈10,000 cases were reported in 2020 15, 16.

How do babies and children catch rubella?

Rubella spreads through:

- person-to person contact

- exposure to the droplets released when an infected person coughs or sneezes

A child with rubella can infect others from 1 week before their rash appears. They remain contagious up until 2 weeks after the rash appears.

How can I prevent the spread of rubella?

If your child has rubella, do not send them to childcare, kindergarten or school where they could infect others. Make sure that you and your family are observing good hygiene practices, including washing hands both properly and frequently.

Try and teach your child the importance of sneezing and coughing into their elbow. This helps prevent the spread of the rubella virus, and other illnesses.

It’s especially important to keep your child away from pregnant woman. This is because the virus can be very dangerous for their unborn baby.

Rubella prevention

Vaccination is the best way to prevent rubella. The rubella vaccine is a combination vaccine for measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) or measles, mumps, rubella and varicella [chickenpox) (MMRV). Both are very effective and have similar side effects. Your doctor can advise which vaccine is right for you.

What can travelers do to prevent rubella?

Getting vaccinated is the best way to protect yourself against rubella. Rubella vaccine is routinely given to children in the United States. The vaccine is given in two doses: children usually get the first dose when they are 12 to 15 months old and the second dose when they are 4 to 6 years old. Rubella vaccine is a combination vaccine that also protects against measles and mumps (MMR vaccine) or measles, mumps, and varicella (MMRV vaccine).

If you were born after 1956 and do not have evidence of immunity, you should get vaccinated with two doses of MMR vaccine before you travel. The second dose is given at least 28 days after the first dose. People born before 1957 do not need to be vaccinated with the MMR vaccine.

Infants 6 to 11 months old traveling internationally should get one dose of MMR vaccine before travel. This dose does not count as part of the routine childhood vaccination series.

Rubella vaccine

Rubella can be prevented with the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine. MMR vaccine protects against three diseases: measles, mumps, and rubella. The rubella vaccine contains live attenuated (weakened) rubella virus. Live vaccines are whole-cell vaccines, meaning the entire virion is used to create the vaccine 17. An attenuated vaccine is a vaccine that reduces the virulence of the pathogen while still keeping it viable 17. The rubella vaccine induces both humoral and cell-mediated immune responses. It produces an IgG humoral immune response in individuals, as well as a cell-mediated immune response by rubella-specific activation of CD4+ T-helper and CD 8+ T-lymphocyte cells. Therefore, the immune response to a live attenuated rubella vaccine is almost identical to one seen during a natural infection 18.

In many places, including the United States, the rubella vaccine is only available as part of the combined measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine (MMR), and the MMR combined with varicella [chickenpox] (MMRV). Both formulations are live attenuated vaccines, meaning that the pathogen has been weakened in the laboratory to decrease its pathogenicity while maintaining its capability to replicate in the vaccinated individual to stimulate an immune response 18.

United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that children get 2 doses of MMR vaccine to protect against rubella 19. Teens and adults should also be up to date on MMR vaccinations. MMR vaccine is very safe and effective. One dose of the MMR vaccine is about 97% effective at preventing rubella.

The MMR or MMRV is given subcutaneously in 2 doses: one at 12 to 15 months and one at 4 to 6 years 20.

Before the introduction of the rubella vaccine, outbreaks of rubella occurred at variable intervals of 3 to 7 years, with the highest incidence among school children. During the last major rubella epidemic in the United States from 1964 to 1965, an estimated 21:

- 12.5 million people got rubella

- 11,000 pregnant people lost their babies

- 2,100 newborns died

- 20,000 babies were born with congenital rubella syndrome.

The rubella vaccine became available in 1969 and the combined measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccination program started in 1971. Once the rubella vaccine became widely used, the number of people infected with rubella in the United States dropped dramatically. Rubella was eliminated in the United States in 2004, but can be brought into the United States by people who get infected in other countries 22. Today, fewer than 10 people in the United States are reported as having rubella each year 21. Since 2012, most rubella cases had evidence that they were infected when they were living or traveling outside the United States 21.

MMR (measles, mumps, and rubella) vaccine

- Contains a combination of measles, mumps, and rubella vaccines.

- Two MMR vaccines are available for use in the United States: M-M-R II and PRIORIX. Both are recommended similarly and considered interchangeable.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that people get MMR vaccine to protect against measles, mumps, and rubella 23.

- Children should get 2 doses of MMR vaccine, starting with the first dose at 12 to 15 months of age, and the second dose at 4 through 6 years of age.

- Teens and adults should also be up to date on their MMR vaccination.

- Older children, adolescents, & adults—Also need 1 or 2 doses of MMR vaccine if they don’t have evidence of immunity. Doses should be separated at least 28 days apart.

- Anyone traveling internationally—Should be fully vaccinated before traveling. Infants 6–11 months old should get 1 dose of the MMR vaccine before travel. Then they should get 2 more doses after their first birthday.

- People at increased risk for mumps during a mumps outbreak—An additional dose of MMR may be needed. Public health authorities will notify you if you are at increased risk and should receive this extra dose. If you already have 2 doses of MMR, it’s not necessary to seek out vaccination; unless the authorities tell you that you are part of this group.

- After exposure to measles, mumps, or rubella

- If you don’t have immunity against these diseases and become exposed to them, talk with your doctor about getting MMR vaccine. It is not harmful to get MMR vaccine after being exposed to measles, mumps, or rubella. Doing so may possibly prevent later disease.

- If you get MMR vaccine within 72 hours of initially being exposed to measles, you may get some protection; or have milder illness. In other cases, you may be given a medicine called immunoglobulin (IG) within 6 days of being exposed to measles. This provides some protection against the disease or illness is milder.

- Unlike with measles, MMR has not been shown to be effective at preventing mumps or rubella in people already infected.

Who should not get MMR vaccine?

Some people should not get MMR vaccine or should wait.

Tell your vaccine provider if the person getting the MMR vaccine 24:

- Has any severe, life-threatening allergies. A person who has ever had a life-threatening allergic reaction after a dose of MMR vaccine, or has a severe allergy to any part of this vaccine, may be advised not to be vaccinated. Ask your doctor if you want information about vaccine components.

- Is pregnant or thinks she might be pregnant. Pregnant women should wait to get MMR vaccine until after they are no longer pregnant. Women should avoid getting pregnant for at least 1 month after getting MMR vaccine.

- Has a weakened immune system due to disease (such as cancer or HIV/AIDS) or medical treatments (such as radiation, immunotherapy, steroids, or chemotherapy).

- Has a parent, brother, or sister with a history of immune system problems.

- Has ever had a condition that makes them bruise or bleed easily.

- Has recently had a blood transfusion or received other blood products. You might be advised to postpone MMR vaccination for 3 months or more.

- Has tuberculosis.

- Has gotten any other vaccines in the past 4 weeks. Live vaccines given too close together might not work as well.

- Is not feeling well. A mild illness, such as a cold, is usually not a reason to postpone a vaccination. Someone who is moderately or severely ill should probably wait. Your doctor can advise you.

MMRV (measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella) vaccine

- MMRV vaccine contains a combination of measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella (chickenpox) vaccines.

- MMRV vaccine can prevent measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella.

- One MMRV vaccine is available for use in the United States: ProQuad is a combination measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella (MMRV) vaccine 25.

- MMRV vaccine (ProQuad) is only licensed for use in children who are 12 months through 12 years of age 23, 26:

- First dose at age 12 through 15 months

- Second dose at age 4 through 6 years (second dose can also be given 3 months after 1st dose)

- CDC recommends that children get one dose of MMRV vaccine at 12 through 15 months of age, and the second dose at 4 through 6 years of age. Children can receive the second dose of MMRV vaccine earlier than 4 through 6 years. This second dose of MMRV vaccine can be given 3 months after the first dose. A doctor can help parents decide whether to use this vaccine or MMR vaccine.

MMRV vaccine common side effects:

- Sore arm from the injection, redness where the shot is given, fever, and a mild rash can happen after MMRV vaccination.

- Swelling of the glands in the cheeks or neck or temporary pain and stiffness in the joints sometimes occur after MMRV vaccination.

- Mild rash. If a person develops a rash after MMRV vaccination, it could be related to either the measles or the varicella component of the vaccine. The varicella vaccine virus could be spread to an unprotected person. Anyone who gets a rash should stay away from infants and people with a weakened immune system until the rash goes away. Talk with your health care provider to learn more.

- Fever.

- Seizures, often associated with fever, can happen after MMRV vaccine. The risk of seizures is higher after MMRV than after separate MMR and varicella vaccines when given as the first dose of the two-dose series in younger children. Your doctor can advise you about the appropriate vaccines for your child.

- People sometimes faint after medical procedures, including vaccination. Tell your doctor if you feel dizzy or have vision changes or ringing in the ears.

- More serious reactions happen rarely, including temporary low platelet count (thrombocytopenia), which can cause unusual bleeding or bruising.

- In people with serious immune system problems, this vaccine may cause an infection that may be life-threatening. People with serious immune system problems should not get MMRV vaccine.

Some children who get MMRV vaccine may have a febrile seizure after getting the shot 27. A personal or family history of seizures is a precaution for MMRV vaccination; this is because a recent study found an increased risk for febrile seizures in children 12-23 months who receive MMRV compared with MMR and varicella vaccine 28. However, these seizures are not common and have not been associated with any long-term problems.

Rarely, the MMRV vaccine can cause swelling of neck or cheeks or a temporary low platelet count. Extremely rarely, the vaccine’s ingredients cause severe allergic (anaphylactic) reactions 29. Children should not get MMRV vaccine if they have ever had a life-threatening allergic reaction to any component of the vaccine, including gelatin or the antibiotic neomycin 30.

Who should not get MMRV vaccine?

Some people should not get MMRV vaccine or should wait.

Tell your vaccine provider if the person getting the MMRV vaccine 31:

- Has had an allergic reaction after a previous dose of MMRV, MMR, or varicella vaccine, or has any severe, life-threatening allergies

- Is pregnant or thinks they might be pregnant—pregnant people should not get MMRV vaccine

- Has a weakened immune system, or has a parent, brother, or sister with a history of hereditary or congenital immune system problems

- Has ever had a condition that makes him or her bruise or bleed easily

- Has a history of seizures, or has a parent, brother, or sister with a history of seizures

- Is taking or plans to take salicylates (such as aspirin)

- Has recently had a blood transfusion or received other blood products

- Has tuberculosis

- Has gotten any other vaccines in the past 4 weeks

Additionally, you should wait to get the MMRV vaccine and tell their doctor if you:

- Have a history of seizures, or has a parent, brother, or sister with a history of seizures.

- Are taking or plans to take salicylates (such as aspirin).

In some cases, your health care provider may decide to postpone MMRV vaccination until a future visit or may recommend that the child receive separate MMR and varicella (chickenpox) vaccines instead of MMRV.

People with minor illnesses, such as a cold, may be vaccinated. Children who are moderately or severely ill should usually wait until they recover before getting MMRV vaccine.

I’m planning a pregnancy — should I be vaccinated?

If you are planning pregnancy, speak to your doctor about the rubella screening test. This is a simple blood test called the rubella antibody screening. It checks to see if you have rubella antibodies. Rubella antibodies are a type of protein that helps your body fight rubella. In most cases, previous rubella infection or vaccination will make you immune to rubella, meaning that you can’t be infected again.

If you don’t have rubella antibodies, you may be offered MMR vaccine to protect you and any future pregnancies.

If you are vaccinated with the MMR vaccine, you should avoid falling pregnant for at least 28 days.

If you are pregnant and are not vaccinated, you should wait to get MMR vaccine until after you have given birth.

It’s safe to have the MMR vaccine after your baby is born, even if you are breastfeeding.

Should I get vaccinated after being exposed to measles, mumps, or rubella?

Anyone who is not vaccinated against measles, mumps, or rubella is at risk of getting measles, mumps, or rubella. If you do not have immunity against measles, mumps, and rubella and are exposed to someone with one of these diseases, talk with your doctor about getting MMR vaccine. It is not harmful to get MMR vaccine after being exposed to measles, mumps, or rubella, and doing so may possibly prevent later disease 23.

If you get MMR vaccine within 72 hours of initially being exposed to measles, you may get some protection against the disease, or have milder illness 23. In other cases, you may be given a medicine called immunoglobulin (IG) within six days of being exposed to measles, to provide some protection against the disease, or have milder illness.

Unlike with measles, MMR has not been shown to be effective at preventing mumps or rubella in people already infected with the virus (i.e., post-exposure vaccination is not recommended) 23.

During outbreaks of measles or mumps, everyone without presumptive evidence of immunity should be brought up to date on their MMR vaccination. And some people who are already up to date on their MMR vaccination may be recommended to get an additional dose of MMR for added protection against disease 23.

Rubella vaccine near me

Vaccines may be available at private doctor offices, pharmacies, workplaces, community health clinics, health departments or other community locations, such as schools and religious centers. If your primary healthcare provider does not stock all the vaccines recommended for you, ask for a referral. Getting a vaccine at a doctor’s office or health department does not require a patient-specific prescription from another health care provider.

Many local pharmacies offer most recommended vaccines for adults, as well as some travel vaccines. If you plan on getting vaccinated at a pharmacy, consider calling the pharmacy ahead to find out if you need a prescription. The laws governing which vaccines a pharmacist can prescribe or administer vary by state. Some states allow pharmacists to independently administer vaccine without a patient-specific prescription from another health care provider and others do not. Laws governing patient-specific prescription can also vary by patient age or the vaccine needed.

You can also contact your state health department to learn more about where to get vaccines in your community.

Rubella vaccine cost

Most health insurance plans cover the cost of vaccines. However, you may want to check with your insurance provider before going to the doctor. If you don’t have health insurance or if your insurance does not cover vaccines for your child, the Vaccines for Children Program (https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/vfc/index.html) may be able to help. This program helps families of eligible children who might not otherwise have access to vaccines. To find out if your child is eligible, visit the VFC website or ask your child’s doctor. You can also contact your state VFC coordinator here (https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/awardee-imz-websites.html).

Rubella in pregnancy

Rubella is very dangerous for developing babies and can cause congenital rubella syndrome 3. Congenital rubella syndrome can affect almost everything in the developing baby’s body and cause complications after birth.

Congenital rubella syndrome can cause serious problems for your baby, such as:

- intellectual disability

- cataracts (cloudy vision)

- deafness

- heart problems

If you get rubella during pregnancy (first 20 weeks of pregnancy), you are at risk for miscarriage or stillbirth. Your developing baby is at risk for severe birth defects with devastating, lifelong consequences. Infection with rubella virus causes the most severe damage during early in pregnancy, especially in the first 12 weeks (first trimester). The risk of damage to your baby is lower after 16 weeks of pregnancy.

If you are pregnant and have been in contact with someone with rubella, speak to your doctor. Your doctor will arrange a blood test for you.

The best way to protect yourself from catching rubella is through vaccination.

The rubella vaccine is given as a combined vaccination, either as:

- measles-mumps-rubella (MMR)

- measles-mumps-rubella-varicella (MMRV)

You should make sure you are vaccinated against rubella before you get pregnant. However, if you are pregnant, you should NOT get MMR vaccine. MMR vaccine contain a weakened (attenuated) live virus vaccine. There are concerns that if MMR vaccine is given during pregnancy, they may affect the health of your baby. If you are pregnant and are not vaccinated, you should wait to get MMR vaccine until after you have given birth.

Figure 3. Rubella in pregnancy diagnostic algorithm

Footnote: Diagnostic algorithm for the follow-up of women in contact with suspected rubella cases or exposed to rash during pregnancy.

[Source 32 ]Rubella in pregnancy diagnosis

The clinical diagnosis of maternal rubella infection is difficult and unreliable because of its inconsistent and non-specific clinical symptoms. Clinical diagnosis of Rubella is even less reliable in industrialized countries as it has become a rare disease 33, 34. Laboratory diagnosis is essential to confirm a recent rubella infection and is based on the observation of a seroconversion, on the kinetics of rubella virus-IgG, rubella virus-IgM and rubella virus-IgG avidity and on the detection of rubella virus in nasopharyngeal secretions by reverse transcription/polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) 35, 36.

In cases in which a pregnant woman has contact with a suspected rubella case, a serum sample should be tested for rubella virus-IgG as soon as possible (<12 days) to determine her immune status. Rubella virus-IgG-positive result could reassure the patient. If the patient is susceptible, a determination of rubella virus-IgG and rubella virus-IgM titers is recommended 3 weeks later to exclude an asymptomatic primary rubella infection 32. Doctors must be aware that following the primary rubella infection, depending on the patient tested and on the assays used, rubella virus-IgG could reach a steady state in a few days or a few weeks after the onset of the rubella infection. Consequently, a woman seropositive at the first screening test may have been infected a few weeks earlier. Therefore, in case of ultrasound abnormalities (including intrauterine growth retardation), extra serological investigations should be performed on the earliest serum available (especially rubella virus-IgM and rubella virus-IgG avidity testing), and rubella reverse transcription/polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) in amniotic fluid should be discussed even in countries that tend to rubella elimination, and especially if the woman was born in a country that did not implement routine rubella vaccination in childhood 32.

In countries in which the rubella virus has almost disappeared, even in the context of a clinical presentation of the rash, seroconversion and positive rubella virus-IgM assessments must be interpreted with caution, and further testing (rubella virus-IgG avidity and/or immunoblot) in specialized laboratories should be performed 32. Rubella virus-IgM is almost always detected after the primary infection (if sampling is performed in the 2 months following the onset of infection) using the most sensitive technique; therefore, it could be detected in other situations 32. In countries in which rubella vaccination is recommended, a positive rubella virus-IgM result is typically from vaccination or non-specific stimulation of the immune system 32. Low concentrations of rubella virus-IgM could be detected for months and even years after vaccination 37. Rubella virus-IgM could reappear during a re-infection 38 and false-positive reactivity has been reported 39, 40. In countries in which rubella is endemic, a positive rubella virus-IgM has a good predictive value 32.

Rubella virus-specific immunoglobulin G avidity has been shown to benefit the dating of primary rubella infections 32. Different methods are used to measure the avidity index, and they are typically based on the use of a denaturing agent to prevent the binding of a low-avidity antibody to the antigen 41, 42, 43. A low rubella virus-IgG avidity index is frequently measured in recent primary infections (<1–3 months); a high rubella virus-IgG avidity index excludes a recent primary infection (<3 months). Rubella virus-IgG avidity should be interpreted with caution in cases in which the rubella virus-IgG titer is excessively low. After vaccination, the rubella virus-IgG avidity index matures slowly and frequently stabilizes to a moderate value 37.

Ultrasound findings

The most common ultrasound abnormalities are heart septal defects and eye cataracts and one or both of a baby’s eyes are small (microphthalmia) 33. Microcephaly, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly and intrauterine growth retardation are found less frequently 44. No descriptive series of fetal ultrasound findings has been reported that could determine the frequency of these abnormalities. Epidemics frequently occur in developing countries in which fetal ultrasound is not widely practiced. A preliminary study analyzed the role of ultrasonography in the prenatal diagnosis of congenital infection and defined the specificity of ultrasound at 100% and the sensitivity at 11%; however, the series was small 45.

Figure 4. Complications of rubella in pregnancy

Footnote: Fetal face at 19 weeks gestation (coronal view): microphthalmia and hyperechoic lens (arrow)

[Source 32 ]Figure 5. Complications of rubella in pregnancy

Footnote: Fetal face at 19 weeks gestation (coronal view): ophthalmic asymmetry and microphthalmia.

[Source 32 ]Complications of rubella in pregnancy

Complications of rubella in pregnancy and congenital rubella syndrome after maternal rubella infection depend on the gestational age at infection. When infection with rubella occurs before 10 weeks of gestation, it may cause multiple fetal defects in up to 90% of cases. The risk of congenital defects declines with infection later in gestation 1. Miller et al. 46 showed that before 11 weeks gestation, the congenital infection rate approaches 90%, decreases to 30% between 24 and 26 weeks gestation and increases to nearly 100% beyond 36 WG. During the first 12 WG, the risk of major fetal defects nears 85%, with approximately 20% of the cases resulting in spontaneous abortions in the first 8 weeks gestation. The risk declines rapidly and fluctuates between 11 and 18 weeks gestation, approaching 0% after 18 weeks gestation 46.

The risk of fetal infection in cases in which conception occurs after the rash is most likely very low, and the rash is concomitant with the appearance of antibodies and the end of viremia 32. No intrauterine infection has been detected in the children or fetuses whose mothers had a rash before or within 11 days after the last menstrual period 32. Teratogenic infections could occur in pregnancies in which the rubella rash appears 3 to 6 weeks after the last menstrual period 47.

A viral rubella infection during embryogenesis leads to the classic triad of cataracts, cardiac abnormalities and sensorineural deafness, and many other defects might be observed 32. These abnormalities are classified as transient, permanent or late onset 48. The transient defects in newborns include low birth weight, thrombocytopenic purpura, hemolytic anemia, hepatosplenomegaly and meningoencephalitis. Permanent defects include ophthalmic abnormalities (microphthalmia, cataracts and retinopathy), auditory impairment (sensorineural deafness), cardiac defects (patent ductus arteriosus and pulmonary artery hypoplasia), central nervous system manifestations (mental or psychomotor retardation and language delay) and craniofacial malformations (microcephaly) 49. Deafness is the most common defect and could be the only defect observed, particularly in cases in which infection occurs at 12 to 18 weeks gestation. Late-onset manifestations include endocrine, cardiovascular and neurological abnormalities. A review of 125 adults with congenital rubella in United States reported eye damage as the most common disorder (78%), followed by sensorineural deafness (66%), psychomotor retardation (62%) and cardiac defects (58%), and 88% of the cases included other organ defects 50. Additionally, congenital rubella syndrome is associated with autoimmunity diseases, and several studies have reported an increased risk for diabetes and thyroid diseases 51, 52, 53, 54.

Rubella in pregnancy treatment

The management of rubella infection in pregnancy depends on the gestational age at the onset of infection 32:

- Infection before 18 weeks gestation: The fetus is at high risk for infection and severe symptoms. Termination of pregnancy could be discussed and accepted, according to local legislation, particularly if the infection presented before 12 weeks gestation. A detailed ultrasound examination and assessment of amniotic fluid viral RNA are recommended, particularly for infections occurring between 12 and 18 weeks gestation. If a prenatal diagnosis is not performed, a specific pediatric examination must be performed in newborns, including rubella virus-IgM assays.

- Infection after 18 weeks gestation: The pregnancy could be continued with simple ultrasound monitoring. A specific pediatric examination of the newborn and testing for rubella virus-IgM are recommended.

Congenital rubella syndrome

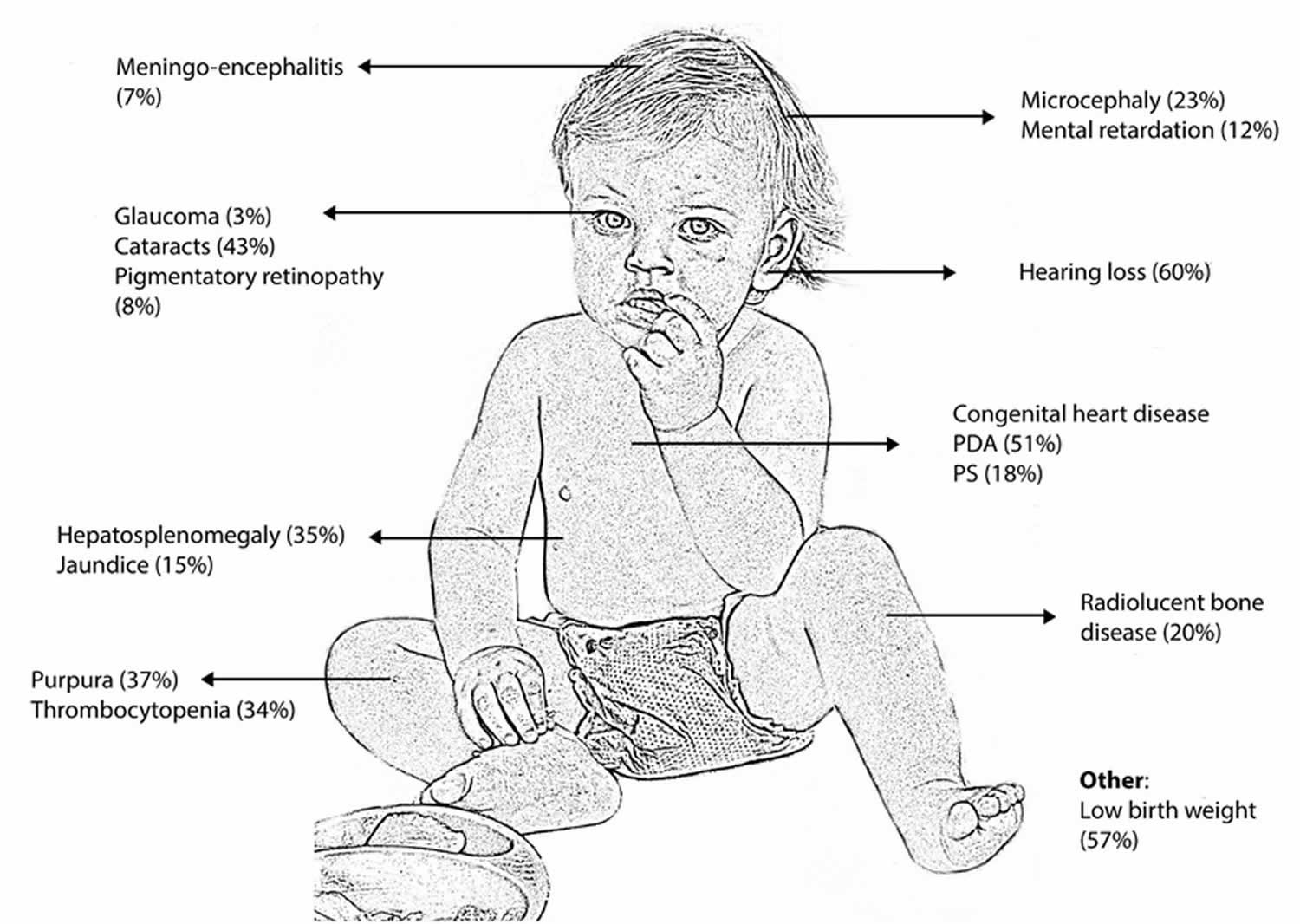

Congenital rubella syndrome is a rare fetal malformation syndrome (group of birth defects) with lifelong consequences that occur in an infant whose mother is infected with the Rubella virus that causes rubella (German measles) during the first trimester of pregnancy. Congenital rubella syndrome occurs when the rubella virus in the mother affects the developing baby in the first 3 months of pregnancy. After the fourth month, if the mother has a rubella infection, it is less likely to harm the developing baby 55. Congenital means the condition is present at birth. Classically congenital rubella syndrome leads to the triad of deafness (80%), congenital cardiac disease (50- 70%, most commonly patent ductus arteriosus or pulmonary stenosis) and cataracts (30%), but many other defects involving almost every organ have been described (Figure 1) 56. The most common problems in congenital rubella syndrome are hearing loss due to damage to the nerve pathways from the inner ear to the brain (sensorineural hearing loss), ocular abnormalities (cataract, infantile glaucoma, and pigmentary retinopathy) and heart problems. Other symptoms and signs may include intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR), prematurity, stillbirth, miscarriage, neurological problems (intellectual disability, low muscle tone, very small head), liver and spleen enlargement (hepatosplenomegaly), jaundice, skin problems, anemia, hormonal problems, and other issues 57.

Congenital rubella syndrome risk is highest if the mother is infected in the first trimester of her pregnancy. Infection during this time carries a risk of congenital rubella syndrome that can be as high as 90%, although spontaneous miscarriage is common 58. Sensorineural deafness can occur with infection right up to the 19th week of gestation and may only become evident later in childhood 59. More severe complications include acute meningo-encephalitis (10 – 20%) and late onset progressive panencephalitis. The risk of intellectual disability, behavioral problems and autism are all increased in children with congenital rubella syndrome. Studies have shown that affected adults also have an increased risk of developing endocrinopathies such as diabetes mellitus and thyroid problems 56. Although congenital rubella syndrome is a disease with a variable spectrum of clinical presentation and outcome, many patients require lifelong care.

There is no cure for congenital rubella syndrome. So, it is important to get vaccinated before you get pregnant.

Support of an infant born with congenital rubella syndrome varies depending on the extent of the infant’s problems. Children who have multiple complications may require early treatment from a team of specialists.

Congenital rubella syndrome has no cure, but it is almost completely preventable by an effective MMR (measles, mumps and rubella vaccine) immunization program. The number of babies born with congenital rubella is much less since the rubella vaccine was developed. Pregnant women who are not vaccinated for rubella and who have not had the disease in the past risk infecting themselves and their unborn baby. One dose of the MMR vaccine is about 97% effective at preventing rubella 60. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends children get two doses of MMR vaccine, starting with the first dose at 12 through 15 months of age, and the second dose at 4 through 6 years of age. Teens and adults also should also be up to date on their MMR vaccination. MMR vaccine is a live attenuated vaccine, and due to its theoretical teratogenic risk, women who are pregnant and not vaccinated should wait to get MMR until after they have given birth 61. Pregnant women should wait to get MMR vaccine until after they are no longer pregnant. Women should avoid getting pregnant for at least 1 month after getting MMR vaccine. Although, several publications have reported the absence of congenital rubella syndrome after vaccination during pregnancy.

Congenital rubella syndrome is a global public health concern with more than 100,000 cases reported annually worldwide 62. Natural rubella infection during pregnancy is one of the few known causes of autism. As many as 8%–13% of children with congenital rubella syndrome developed autism during the rubella epidemic of the 1960s compared to the background rate of about 1 new case per 5000 children 63.

Before the availability of rubella vaccines in the United States in 1969, rubella was a common disease that occurred primarily among young children. The last major epidemic in the United States occurred during 1964 to 1965, when there was an estimated 12.5 million rubella cases in the United States. Because of successful vaccination programs, rubella has been eliminated from the United States since 2004. Since elimination, fewer than 10 congenital rubella syndrome cases have been reported annually in the United States, and most cases were imported from outside the country 64. Unvaccinated people can get rubella while abroad and bring the disease to the United States and spread it to others.

Rubella continues to be a commonly transmitted infection in many parts of the world. Many rubella cases are not recognized, as the rash resembles many other illnesses and up to half of all infections may be subclinical.

Humans are the only source of rubella infection. Transmission is through direct or droplet contact from nasopharyngeal secretions. Once inhaled, the virus replicates in the respiratory mucosa and cervical lymph nodes before reaching the target organs via systemic circulation. The infectious period extends approximately 8 days before to 8 days after the rash onset 65.

Maternal rubella during pregnancy can cause miscarriage, fetal death or congenital rubella syndrome 65. Few infants with congenital rubella continue to spread the virus in nasopharyngeal secretions and urine for a year or more. Rubella virus also has been recovered from lens aspirates in children with congenital cataracts for several years.

Figure 6. Congenital rubella syndrome

Footnote: Common clinical manifestations of congenital rubella syndrome.

[Source 66 ]Figure 7. Congenital rubella (eye cataracts)

Footnote: Eye cataracts (arrows) in case-patient with congenital rubella syndrome.

Congenital rubella syndrome causes

Congenital rubella occurs when the rubella virus in the mother affects the developing baby in the first 3 months of pregnancy. After the fourth month, if the mother has a rubella infection, it is less likely to harm the developing baby.

The number of babies born with congenital rubella is much smaller since the rubella vaccine was developed.

Pregnant women and their unborn babies are at risk if:

- They are not vaccinated for rubella

- They have not had the disease in the past.

Most people who get rubella usually have mild illness, with symptoms that can include a low-grade fever, sore throat, and a rash that starts on the face and spreads to the rest of the body. Some people may also have a headache, pink eye, and general discomfort before the rash appears. Rubella can cause a miscarriage or serious birth defects in an unborn baby if a woman is infected while she is pregnant.

- Congenital rubella infection – Congenital rubella infection encompasses all outcomes associated with intrauterine rubella infection (eg, miscarriage, stillbirth, combinations of birth defects, asymptomatic infection) 67.

- Congenital rubella syndrome – Congenital rubella syndrome refers to variable constellations of birth defects (eg, hearing impairment, congenital heart defects, cataracts/congenital glaucoma, pigmentary retinopathy, etc)

Pathogenesis of congenital rubella syndrome is multifactorial and include the following 65:

- Non-inflammatory necrosis of chorionic epithelium and in endothelial cells which are then transported to fetal circulation and fetal organs.

- Intracellular actin assembly is inhibited by rubella infection, leading to inhibition of mitosis and restricted development of precursor cells.

- Upregulation of cytokines and interferon in infected cells which could contribute to congenital defects.

Congenital rubella syndrome pathophysiology

The pathogenesis of congenital rubella syndrome is multifactorial and not well understood 68, 2.

- Non-inflammatory necrosis in the epithelium of the chorion and in the endothelial cells is observed. These cells are transported to the fetal circulation and fetal organs such as eyes, heart, brain and ears, prompting thrombosis and ischemic lesions.

- Actin assembly is inhibited directly or indirectly in rubella infection, leading to the inhibition of cell mitosis and development of organ precursor cells.

- The immune system might play a role because interferon and cytokines appear to be upregulated in rubella-infected human fetal cells, which could disrupt developing and differentiating cells and thus contribute to congenital defects 69.

In children with congenital rubella syndrome, the rubella virus persists and is detected in urine, saliva and cerebrospinal fluid for several months 70, which could be explained by a defect in cell-mediated immunity 71. T-cell abnormalities have been observed in young adults with congenital rubella syndrome, possibly leading to organ-specific autoimmunity disorders 72.

Congenital rubella syndrome symptoms

Few or no obvious clinical manifestations occur at birth with mild forms of the disease. The incidence of congenital infection with rubella is high during the early and late weeks of gestation (U-shaped distribution), with chances of birth defects much higher if the infection occurs early in pregnancy.

Congenital defects occur in up to 85% of neonates if maternal infection occurs during the first 12 weeks of gestation, in 50% of neonates if infection occurs during the first 13 to 16 weeks of gestation, and 25% if infection occurs during the latter half of the second trimester.

Congenital rubella syndrome include the following 73:

- Congenital heart defects (patent ductus arteriosus, peripheral pulmonary artery stenosis, ventricular septal defects, atrial septal defects)

- Auditory (sensorineural hearing impairment)

- Ophthalmologic (cataracts, pigmentary retinopathy, microphthalmos, chorioretinitis)

- Neurologic (microcephaly, cerebral calcifications, meningoencephalitis, behavioral disorders, mental retardation)

- Hematologic (thrombocytopenia, hemolytic anemia, petechiae/purpura, dermal erythropoiesis causing “blueberry muffin” rash)

- Neonatal manifestations (low birth weight, interstitial pneumonitis, radiolucent bone disease leading to “celery stalking” of long bone metaphyses, hepatosplenomegaly)

- Delayed onset of insulin-dependent diabetes and thyroid disease.

Symptoms in infant with congenital rubella syndrome may include:

- Cloudy corneas or white appearance of pupil (cataracts)

- Deafness

- Developmental delay

- Excessive sleepiness

- Irritability

- Low birth weight

- Below average mental functioning (intellectual disability)

- Seizures

- Small head size

- Liver and spleen damage

- Skin rash at birth

- Glaucoma

- Brain damage

- Thyroid and other hormone problems

- Inflammation of the lungs.

Congenital rubella syndrome diagnosis

Maternal screening with rubella titers in early pregnancy is considered standard of care in the United States 62. Rubella-like illness in early pregnancy should be evaluated to confirm the diagnosis. Laboratory diagnosis is based on observation of seroconversion with use of rubella-specific-IgG and IgM antibody in the cord blood or in the neonatal serum collected within the first 6 months of life 74, 75. In infants older than 3 months, a negative rubella-specific IgM does not exclude a congenital rubella infection although a positive test does support the diagnosis 76. Congenital rubella infection can also be confirmed by demonstrating persistent or increasing serum concentrations of rubella-specific IgG over the first 7 to 11 months of life 74. Detection of rubella virus RNA by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) in nasopharyngeal swab or urine provides laboratory evidence of congenital rubella syndrome.

Prenatal fetal diagnosis is based on detection of viral genome in amniotic fluid, fetal blood or chorionic villus biopsies.

Postnatal diagnosis of congenital rubella infection is done by detecting rubella virus-IgG antibodies in neonatal serum using ELISA. This approach has sensitivity and specificity of nearly 100% in infants less than three months of age. Confirmation of infection is made by detection of rubella virus in nasopharyngeal swabs, urine and oral fluid using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) 65.

Congenital infection can also be confirmed by stable or increasing serum concentrations of rubella-specific IgG over the first year of life. Maternal counseling and termination of pregnancy are options in such cases. It is difficult to diagnose congenital rubella in children older than one year of age.

Postnatal confirmation of congenital infection is important despite the absence of clinical features of congenital rubella syndrome. This is to develop a specific follow-up care plan for early detection of long-term neurological and ocular complications 77.

Prenatal diagnosis of congenital infection

A prenatal diagnosis of congenital infection is recommended when a maternal infection is diagnosed and is based on the detection of rubella-specific-IgM in fetal blood or on the detection of the viral genome in amniotic fluid, fetal blood or chorionic villus biopsies 70, 78. The detection of rubella virus in chorionic villus biopsies reflects an infection of the villi, not a fetal infection.

The specificity of a prenatal diagnosis is approximately 100%, and the sensitivity is greater than 90% if the following conditions are met 78:

- At least a 6-week period passes between the infection and sampling;

- A sample collection is performed after 21 weeks gestation; and

- The samples for reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) are stored and transported frozen (fetal blood for rubella virus-IgM detection is stored and transported at 4 °C).

Postnatal diagnosis of congenital infection

A postnatal diagnosis of congenital infection is based on the detection of a specific rubella virus-IgM by immunocapture ELISA, which has sensitivity and specificity that approach 100% in infected newborns (<3 months of age) 79. In cases in which the rubella virus-IgM test is positive, a congenital infection might be confirmed by isolating the rubella virus or by detecting the viral genome in nasopharyngeal swabs, urine and oral fluid using reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) 80.

Performing a postnatal diagnosis of a congenital infection is important, regardless of whether a clinical manifestation of congenital rubella syndrome is observed, to provide a specific follow-up care plan if an infection is discovered (including neurological and hearing monitoring) 70.

A child infected in utero could excrete the virus in saliva and urine for several months or years.

Congenital rubella syndrome treatment

Although symptoms associated with congenital rubella syndrome can be treated, there is no cure for the congenital rubella syndrome; hence, prevention should be the goal. There is no treatment is available for congenital rubella syndrome, it is important for women to get vaccinated before they get pregnant.

Congenital rubella syndrome is a chronic disease, and these children need to be followed up to detect progression and the emergence of new problems. A multidisciplinary team approach is required, involving pediatric, ophthalmologic, cardiac, audiological, neurodevelopmental evaluation, educational and rehabilitative management. Long-term follow up is needed to monitor for delayed manifestations 2.

Prenatal management of the mother and fetus depends on gestational age at onset of infection. If infection happens before 18 weeks gestation, the fetus is at high risk for infection and severe symptoms. Termination of pregnancy could be discussed based on local legislation. Detailed ultrasound examination and assessment of viral RNA in amniotic fluid is recommended.

For infections after 18 weeks of gestation, pregnancy could be continued with ultrasound monitoring followed by neonatal physical examination and testing for rubella virus-IgG 65.

Limited data suggest a benefit of intramuscular immune globulin (Ig) for maternal rubella infection leading to decrease in viral shedding and risk of fetal infection.

Control measures

Children with congenital rubella syndrome should be considered contagious until at least one year of age unless two negative cultures are obtained one month apart after 3 months of age. Neonates should be isolated. Hand hygiene is of utmost importance for reducing disease transmission from the urine of children with congenital rubella infection 81.

Congenital rubella syndrome long term effects

Children with congenital rubella syndrome prognosis varies depending on the severity and number of organs affected. The risk of mortality risk is high in infants with thrombocytopenia, interstitial pneumonia, hepatosplenomegaly, and pulmonary hypertension 2. Also, individuals with congenital rubella syndrome are at risk of long-term complications, including blindness, cardiac failure, developmental delays, and reduced life expectancy 82.

Rubella symptoms

Rubella is usually mild, with few noticeable symptoms. For children who do have symptoms, a pink or red rash appearing on the face is typically the first sign.

Most adults who get rubella usually have a mild illness with:

- Low-grade fever

- Sore throat

- Headache

- Conjunctivitis (redness or swelling of the white of the eye)

- Nausea

- Fever

- Generally feeling unwell

- Swollen glands. Swollen glands caused by rubella are usually found at the back of your neck and behind your ears

- A rash that starts on the face and spreads to the rest of the body (neck, upper body, arms and legs). The rash itself may appear as small dots which form a larger, reddened area. The rash can last up to 5 days and may or may not be itchy.

Petechiae on the soft palate (Forchheimer spots) can also be observed in approximately 20% of the patients 7.

Up to 70% of women may experience arthritis as a rubella complication; this is rare in children and men.

The joints most affected are the:

- fingers

- wrists

- knees

Joint symptoms usually start at the same time as the rash appears. These symptoms may persist for weeks.

Symptoms of rubella will generally begin to show about 14 days after infection. However, as many as 1 in 2 people who have the rubella virus do not feel unwell.

Rubella in children

For children with rubella who do have symptoms, a pink or red rash is typically the first sign. The rash generally first appears on the face and then spreads to the rest of the body, lasting about 3 to 4 days. The rash may appear in the form of many small dots which together form a larger, reddened area. Sometimes the rash is itchy.

Other symptoms that may occur 1 to 5 days before the rash appears include:

- Low-grade fever

- Headache

- Mild pink eye (redness or swelling of the white of the eye)

- General discomfort or feeling unwell

- Swollen and enlarged lymph nodes (especially at the back of a child’s neck and behind their ears)

- Sore throat and a runny nose

- Cough

- Runny nose

Symptoms generally begin to show about 14 days after a child has been infected with rubella.

Rubella in adults

Most adults who get rubella usually have a mild illness, with:

- Low-grade fever

- Sore throat

- A rash that starts on the face and spreads to the rest of the body

Some adults may also have a headache, pink eye, and general discomfort before the rash appears.

Up to 70% of women who get rubella may experience arthritis. This is rare in children and men.

Rubella complications

In rare cases, rubella can cause serious problems, including brain infections and bleeding problems.

The most serious complication from rubella infection is the harm it can cause a developing baby. This can happen in the womb and after birth.

If an unvaccinated person gets infected with rubella during pregnancy they can have a miscarriage; or the baby can die just after birth. They can pass the virus to the developing baby who can develop serious birth defects, such as:

- Heart problems

- Loss of hearing and eyesight

- Intellectual disability

- Liver or spleen damage

Serious birth defects are more common if a woman is infected early in her pregnancy, especially in the first trimester. These severe birth defects are known as congenital rubella syndrome.

About 9 out of 10 babies, born to people who catch rubella during the first trimester of pregnancy, become affected by congenital rubella syndrome.

Birth defects associated with congenital rubella syndrome include:

- low birthweight

- cognitive impairment

- hearing loss

- heart problems

- eye problems, such as cataracts

Rubella diagnosis

Your doctor may be able to diagnose rubella from your symptoms and history of possible exposure to rubella.

Your doctor may confirm the diagnosis with a blood test.

Rubella is a notifiable disease. This means that if your child has rubella, your doctor will notify your local public health unit. They may ask to talk with you to try and find out:

- where you or your child caught rubella

- who you or your child has spent time with (contact tracing)

This helps limit the spread of rubella and protects your community.

Generally, clinical diagnosis of rubella is unreliable because the clinical signs and symptoms of rubella can be mild and non-specific especially in young children 2. In addition, there are many other viral infections having similar clinical features. Laboratory confirmation of rubella virus infection is therefore essential. The diagnosis of a recent postnatal rubella infection can be based on a positive serological test for rubella-specific immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibody in a single sample or a four-fold or greater increase in rubella-specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) titers between acute and convalescent sera drawn 2 to 3 weeks apart 1, 83, 84, 85. Among all the serologic tests available, enzyme linked immunoassays (ELISA) are most commonly used to measure rubella-specific IgG and IgM because they are very sensitive, highly specific, technically easy to perform, rapid, and relatively inexpensive 84, 86. Rubella-specific IgM antibody is present in approximately 50% of patients on the day of appearance of the rash but in almost all the cases 5 days after the onset of rash; the IgM antibody tends to persist ≥8 weeks 1. As such, rubella-specific IgM antibody might be falsely negative if the test is conducted early. In contrast, false positive results may rarely occur in patients with heterophile antibodies, rheumatoid factors, parvovirus B19 infection, and cytomegalovirus infection 74. The use of IgM-capture ELISA rather than indirect IgM ELISA may reduce the occurrence of false positive results 74. When the first serum sample was collected months after clinical symptoms, avidity (strength of antigen-antibody binding) test of rubella-specific IgG antibody, if available, can be used to differentiate a recent primary infection from a past infection or reinfection 87, 1. Low avidity anti-rubella IgG suggests recent primary rubella infection while high avidity is consistent with previous rubella vaccination, past rubella infection, or reinfection 87, 1, 3.

Although rubella virus can be isolated most consistently from nasopharyngeal and throat specimens, viral culture is generally not necessary because viral culture is expensive, time-consuming, and not readily available. Rubella virus culture is done mainly for academic and epidemiological purposes to facilitate surveillance during outbreaks 86. Rubella virus RNA testing by real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), if available, may be performed for diagnosis and genotype identification 74.

Natural immunity

The accurate diagnosis of rubella infection depends on an understanding of antibody kinetics. Rubella specific-IgM appear within 3 days after the rash and generally disappear in 4 to 12 weeks (the levels are divided by 2 every 3 weeks), primarily depending on the assay used. Rubella specific-IgG detected by ELISA appear slightly later (5–8 days after the onset of the rash) and persist throughout life. Rubella specific-IgG reach a steady state at any time from a few days to a few weeks, and the maximal and residual Rubella specific-IgG rates are extremely variable, depending on the patient tested and the assay used. A high Rubella specific-IgG titer is not necessarily a marker of a recent primary infection.

Rubella immunity status

In developed countries, women of childbearing age are routinely screened for rubella antibodies to identify and vaccinate susceptible women 88, 89.

In France, the 2009 national recommendations stated, ‘Given the current epidemiological situation, it is recommended that rubella serology is offered upon the first prenatal visit, unless there is written evidence of immunity or two doses of rubella vaccine documented’. If a patient is initially seronegative, another serology is performed at 20 weeks of gestation; women who remain seronegative at 20 weeks of gestation are offered vaccination after delivery 90.

Immunity to rubella is normally determined by measuring the rubella virus-IgG with enzyme immunoassays that provide quantitative results in international units (IU) per milliliter. The rubella virus-IgG results and interpretation may be discordant, depending on the assay used, although the results are expressed in IU per milliliter and all the immunoassays are calibrated with the identical international standard (RUB-1-94). Preliminary studies indicate that the women are typically immune in cases in which discrepant results are observed. Specific assays such as immunoblots are used in these cases. Latex agglutination tests, which are qualitative or semi-quantitative assays, are no longer recommended 88, 91.

Rubella treatment

There’s no specific treatment for rubella and the disease is usually very mild. Antibiotics will not help you recover from rubella faster because a virus, and not bacteria, causes rubella. Antibiotics are for treating infections caused by bacteria.

Most people recover from rubella by themselves without medical treatment.

Strategies to try to relieve your symptoms at home include:

- getting plenty of rest

- drinking lots of fluids

- taking acetaminophen (paracetamol) to relieve fever

Rubella prognosis

Postnatal infection with rubella is generally mild, self-limited, and has an excellent prognosis. However, the prognosis of children with congenital rubella syndrome is less favorable and varies depending on the severity and number of organs affected. The risk of mortality risk is high in infants with thrombocytopenia, interstitial pneumonia, hepatosplenomegaly, and pulmonary hypertension 2. Also, individuals with congenital rubella syndrome are at risk of long-term complications, including blindness, cardiac failure, developmental delays, and reduced life expectancy 82.

- Lambert N, Strebel P, Orenstein W, Icenogle J, Poland GA. Rubella. Lancet. 2015 Jun 6;385(9984):2297-307. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60539-0[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Leung AKC, Hon KL, Leong KF. Rubella (German measles) revisited. Hong Kong Med J. 2019 Apr;25(2):134-141. https://www.hkmj.org/abstracts/v25n2/134.htm[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Bouthry E, Picone O, Hamdi G, Grangeot-Keros L, Ayoubi JM, Vauloup-Fellous C. Rubella and pregnancy: diagnosis, management and outcomes. Prenat Diagn. 2014 Dec;34(13):1246-53. doi: 10.1002/pd.4467[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- McLean HQ, Fiebelkorn AP, Temte JL, Wallace GS; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention of measles, rubella, congenital rubella syndrome, and mumps, 2013: summary recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2013 Jun 14;62(RR-04):1-34. Erratum in: MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015 Mar 13;64(9):259.[↩][↩]

- Yazigi A, De Pecoulas AE, Vauloup-Fellous C, Grangeot-Keros L, Ayoubi JM, Picone O. Fetal and neonatal abnormalities due to congenital rubella syndrome: a review of literature. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017 Feb;30(3):274-278. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2016.1169526[↩][↩]

- Sherilyn S. Infections characterized by fever and rash. In: Nelson Essentials of Pediatrics. 6th ed. Karen M, Robert K, Hal J, Richard B, Eds. Saunders, Philadelphia, 2010: 390.[↩]

- Fukuda M, Harada T, Shimizu T, Hiroshige J. Forchheimer Spots in Rubella. Intern Med. 2020 Jul 1;59(13):1673. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.4368-19[↩][↩]

- Frey TK. Molecular biology of rubella virus. Adv Virus Res. 1994;44:69-160. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(08)60328-0[↩]

- Pukuta E, Waku-Kouomou D, Abernathy E, Illunga BK, Obama R, Mondonge V, Dahl BA, Maresha BG, Icenogle J, Muyembe JJ. Genotypes of rubella virus and the epidemiology of rubella infections in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2004-2013. J Med Virol. 2016 Oct;88(10):1677-84. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24517[↩]

- Dominguez G, Wang CY, Frey TK. Sequence of the genome RNA of rubella virus: evidence for genetic rearrangement during togavirus evolution. Virology. 1990 Jul;177(1):225-38. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90476-8[↩]

- Chaye H, Chong P, Tripet B, Brush B, Gillam S. Localization of the virus neutralizing and hemagglutinin epitopes of E1 glycoprotein of rubella virus. Virology. 1992 Aug;189(2):483-92. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90572-7[↩]

- Ho-Terry L, Terry GM, Cohen A, Londesborough P. Immunological characterisation of the rubella E 1 glycoprotein. Brief report. Arch Virol. 1986;90(1-2):145-52. doi: 10.1007/BF01314152[↩]

- Best JM, Thomson A, Nores JR, O’Shea S, Banatvala JE. Rubella virus strains show no major antigenic differences. Intervirology. 1992;34(3):164-8. doi: 10.1159/000150277[↩]

- World Health Organization; Global measles and rubella strategic plan: 2012–2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012.[↩]

- World Health Organization. Rubella vaccines: WHO position paper. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2020;95(27):306–24.[↩]

- Vynnycky E, Adams EJ, Cutts FT, Reef SE, Navar AM, Simons E, Yoshida LM, Brown DW, Jackson C, Strebel PM, Dabbagh AJ. Using Seroprevalence and Immunisation Coverage Data to Estimate the Global Burden of Congenital Rubella Syndrome, 1996-2010: A Systematic Review. PLoS One. 2016 Mar 10;11(3):e0149160. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149160[↩]

- Mahmood R, Gerriets V, Tadi P. Rubella Vaccine. [Updated 2023 Jul 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560845[↩][↩]

- Strikas RA; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP); ACIP Child/Adolescent Immunization Work Group. Advisory committee on immunization practices recommended immunization schedules for persons aged 0 through 18 years–United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015 Feb 6;64(4):93-4.[↩][↩]

- Rubella Vaccination. https://www.cdc.gov/rubella/vaccines/index.html[↩]

- Marin M, Broder KR, Temte JL, Snider DE, Seward JF; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Use of combination measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010 May 7;59(RR-3):1-12.[↩]

- Impact of U.S. MMR Vaccination Program. https://www.cdc.gov/rubella/vaccine-impact/index.html[↩][↩][↩]

- Al Hammoud R, Murphy JR, Pérez N. Imported Congenital Rubella Syndrome, United States, 2017. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018 Apr;24(4):800-801. doi: 10.3201/eid2404.171540[↩]

- Measles, Mumps, and Rubella (MMR) Vaccination: What Everyone Should Know. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/mmr/public/index.html#what-is-mmr[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- MMR (Measles, Mumps, and Rubella) VIS. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/vis/vis-statements/mmr.html[↩]

- PROQUAD. https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/vaccines/proquad[↩]

- https://www.fda.gov/media/75203/download[↩]

- Measles, Mumps, Rubella, Varicella (MMRV) Vaccine Safety. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccine-safety/vaccines/mmrv.html#cdc_generic_section_2-available-vaccine-manufacturer-package-insert[↩]

- Marin M, Broder KR, Temte JL, Snider DE, Seward JF; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Use of combination measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010 May 7;59(RR-3):1-12. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5903a1.htm[↩]

- Vaccine Recommendations and Guidelines of the ACIP. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/acip-recs/general-recs/contraindications.html[↩]

- Measles, Mumps, and Rubella (MMR) Vaccination: What Everyone Should Know. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/mmr/public/index.html[↩]

- MMRV (Measles, Mumps, Rubella & Varicella) VIS. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/vis/vis-statements/mmrv.html[↩]

- Bouthry E., Picone O., Hamdi G., Grangeot-Keros L., Ayoubi J.-M., and Vauloup-Fellous C. (2014), Rubella and pregnancy: diagnosis, management and outcomes, Prenat Diagn, 34, 1246–1253, doi: 10.1002/pd.4467[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Cordier AG, Vauloup-Fellous C, Grangeot-Keros L, Pinet C, Benachi A, Ayoubi JM, Picone O. Pitfalls in the diagnosis of congenital rubella syndrome in the first trimester of pregnancy. Prenat Diagn. 2012 May;32(5):496-7. doi: 10.1002/pd.2943[↩][↩]

- Best JM, O’Shea S, Tipples G, Davies N, Al-Khusaiby SM, Krause A, Hesketh LM, Jin L, Enders G. Interpretation of rubella serology in pregnancy–pitfalls and problems. BMJ. 2002 Jul 20;325(7356):147-8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7356.147[↩]

- Best JM, Enders G. Chapter 3 Laboratory diagnosis of rubella and congenital rubella. Perspect Med Virol 2006; 15: 39–77. [↩]

- Manual for the Laboratory Diagnosis of Measles and Rubella Virus Infection ( 2nd edn). Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO), 2007.[↩]

- Vauloup-Fellous C, Grangeot-Keros L. Humoral immune response after primary rubella virus infection and after vaccination. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2007 May;14(5):644-7. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00032-07[↩][↩]

- Grangeot-Keros L, Nicolas JC, Bricout F, Pillot J. Rubella reinfection and the fetus. N Engl J Med. 1985 Dec 12;313(24):1547. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198512123132418[↩]

- Thomas HI, Barrett E, Hesketh LM, Wynne A, Morgan-Capner P. Simultaneous IgM reactivity by EIA against more than one virus in measles, parvovirus B19 and rubella infection. J Clin Virol. 1999 Oct;14(2):107-18. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(99)00051-7[↩]

- Kurtz JB, Anderson MJ. Cross-reactions in rubella and parvovirus specific IgM tests. Lancet. 1985 Dec 14;2(8468):1356. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)92647-9[↩]

- Grangeot-Keros L. L’avidité des IgG: implications en infectiologie. Immuno-Anal Biol Spéc 2001; 16: 87–91.[↩]

- Mubareka S, Richards H, Gray M, Tipples GA. Evaluation of commercial rubella immunoglobulin G avidity assays. J Clin Microbiol. 2007 Jan;45(1):231-3. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01243-06[↩]

- Vauloup-Fellous C, Ursulet-Diser J, Grangeot-Keros L. Development of a rapid and convenient method for determination of rubella virus-specific immunoglobulin G avidity. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2007 Nov;14(11):1416-9. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00312-07[↩]

- Callen P. Ultrasound in Obstetric and Gynaecology ( 4th edn). Philadelphia: Saunders Company, 2000.[↩]

- Migliucci A, Di Fraja D, Sarno L, Acampora E, Mazzarelli LL, Quaglia F, Mallia Milanes G, Buffolano W, Napolitano R, Simioli S, Maruotti GM, Martinelli P. Prenatal diagnosis of congenital rubella infection and ultrasonography: a preliminary study. Minerva Ginecol. 2011 Dec;63(6):485-9.[↩]

- Miller E, Cradock-Watson JE, Pollock TM. Consequences of confirmed maternal rubella at successive stages of pregnancy. Lancet. 1982 Oct 9;2(8302):781-4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)92677-0[↩][↩]

- Enders G, Nickerl-Pacher U, Miller E, Cradock-Watson JE. Outcome of confirmed periconceptional maternal rubella. Lancet. 1988 Jun 25;1(8600):1445-7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)92249-0[↩]

- Cooper LZ, Alford CA Jr. Chapter 28 – rubella. In Infectious Diseases of the Fetus and Newborn Infant ( 6th edn). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 2006; 893–926.[↩]

- Oster ME, Riehle-Colarusso T, Correa A. An update on cardiovascular malformations in congenital rubella syndrome. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2010 Jan;88(1):1-8. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20621[↩]

- Givens KT, Lee DA, Jones T, Ilstrup DM. Congenital rubella syndrome: ophthalmic manifestations and associated systemic disorders. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993 Jun;77(6):358-63. doi: 10.1136/bjo.77.6.358[↩]

- Ginsberg-Fellner F, Witt ME, Fedun B, Taub F, Dobersen MJ, McEvoy RC, Cooper LZ, Notkins AL, Rubinstein P. Diabetes mellitus and autoimmunity in patients with the congenital rubella syndrome. Rev Infect Dis. 1985 Mar-Apr;7 Suppl 1:S170-6. doi: 10.1093/clinids/7.supplement_1.s170[↩]

- Takasu N, Ikema T, Komiya I, Mimura G. Forty-year observation of 280 Japanese patients with congenital rubella syndrome. Diabetes Care. 2005 Sep;28(9):2331-2. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.9.2331[↩]

- Forrest JM, Turnbull FM, Sholler GF, Hawker RE, Martin FJ, Doran TT, Burgess MA. Gregg’s congenital rubella patients 60 years later. Med J Aust. 2002 Dec 2-16;177(11-12):664-7. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb05003.x[↩]

- Clarke WL, Shaver KA, Bright GM, Rogol AD, Nance WE. Autoimmunity in congenital rubella syndrome. J Pediatr. 1984 Mar;104(3):370-3. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(84)81097-5[↩]

- Congenital rubella. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/001658.htm[↩]

- Remington JS, Klein JO, Wilson CB, Nizet V, Maldonado YA. Infectious Diseases of the Fetus and Newborn Infant. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2011:861-898.[↩][↩]

- Pediatric Rubella Clinical Presentation. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/968523-clinical#showall[↩]

- Best JM, O’Shea S, Tipples G, et al. Interpretation of rubella serology in pregnancy – pitfalls and problems. BMJ 2002;325:147-148.[↩]

- Cooper LZ. The history and medical consequences of rubella. Reviews of Infectious Diseases 1985;7(1):S2-S10.[↩]

- Rubella (German Measles) Vaccination. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/rubella/index.html[↩]

- MMR (Measles, Mumps, & Rubella) Vaccine Information Statements. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/vis/vis-statements/mmr.html[↩]

- Shukla S, Maraqa NF. Congenital Rubella. [Updated 2019 Jun 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507879[↩][↩]

- Mawson AR, Croft AM. Rubella Virus Infection, the Congenital Rubella Syndrome, and the Link to Autism. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(19):3543. Published 2019 Sep 22. doi:10.3390/ijerph16193543 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6801530[↩]

- Al Hammoud R, Murphy JR, Pérez N. Imported Congenital Rubella Syndrome, United States, 2017. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24(4):800–801. doi:10.3201/eid2404.171540 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5875265[↩]

- Bouthry E, Picone O, Hamdi G, Grangeot-Keros L, Ayoubi JM, Vauloup-Fellous C. Rubella and pregnancy: diagnosis, management and outcomes. Prenat. Diagn. 2014 Dec;34(13):1246-53.[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Boshoff, L & Tooke, Lloyd. (2012). Congenital rubella: Is it nearly time to take action?. South African Journal of Child Health. 6. 10.7196/sajch.461[↩]

- Reef SE, Plotkin S, Cordero JF, et al. Preparing for elimination of congenital Rubella syndrome (CRS): summary of a workshop on CRS elimination in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31(1):85–95. doi:10.1086/313928[↩]

- Lee JY, Bowden DS. Rubella virus replication and links to teratogenicity. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000 Oct;13(4):571-87. doi: 10.1128/CMR.13.4.571[↩]

- Adamo MP, Zapata M, Frey TK. Analysis of gene expression in fetal and adult cells infected with rubella virus. Virology. 2008 Jan 5;370(1):1-11. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.08.003[↩]

- Best JM, Enders G. Chapter 3 Laboratory diagnosis of rubella and congenital rubella. Perspect Med Virol 2006; 15: 39–77.[↩][↩][↩]

- Buimovici-Klein E, Lang PB, Ziring PR, Cooper LZ. Impaired cell-mediated immune response in patients with congenital rubella: correlation with gestational age at time of infection. Pediatrics. 1979 Nov;64(5):620-6.[↩]

- Rabinowe SL, George KL, Loughlin R, Soeldner JS, Eisenbarth GS. Congenital rubella. Monoclonal antibody-defined T cell abnormalities in young adults. Am J Med. 1986 Nov;81(5):779-82. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(86)90344-x[↩]

- Kaushik A, Verma S, Kumar P. Congenital rubella syndrome: A brief review of public health perspectives. Indian J Public Health. 2018 Jan-Mar;62(1):52-54.[↩]

- Kimberlin DW, Brady MT, Jackson MA, Long SS, editors. Red Book: 2018 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 31st ed. Itasca: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2018: 705-11.[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Dobson SR. Congenital rubella syndrome: clinical features and diagnosis. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/congenital-rubella-syndrome-clinical-features-and-diagnosis[↩]

- Banatvala JE, Brown DW. Rubella. Lancet. 2004 Apr 3;363(9415):1127-37. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15897-2[↩]

- Vauloup-Fellous C. Standardization of rubella immunoassays. J. Clin. Virol. 2018 May;102:34-38.[↩]

- Macé M, Cointe D, Six C, Levy-Bruhl D, Parent du Châtelet I, Ingrand D, Grangeot-Keros L. Diagnostic value of reverse transcription-PCR of amniotic fluid for prenatal diagnosis of congenital rubella infection in pregnant women with confirmed primary rubella infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2004 Oct;42(10):4818-20. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.10.4818-4820.2004[↩][↩]

- Thomas HI, Morgan-Capner P, Cradock-Watson JE, Enders G, Best JM, O’Shea S. Slow maturation of IgG1 avidity and persistence of specific IgM in congenital rubella: implications for diagnosis and immunopathology. J Med Virol. 1993 Nov;41(3):196-200. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890410305[↩]

- Bosma TJ, Corbett KM, Eckstein MB, O’Shea S, Vijayalakshmi P, Banatvala JE, Morton K, Best JM. Use of PCR for prenatal and postnatal diagnosis of congenital rubella. J Clin Microbiol. 1995 Nov;33(11):2881-7. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.11.2881-2887.1995[↩]

- Obam Mekanda FM, Monamele CG, Simo Nemg FB, Sado Yousseu FB, Ndjonka D, Kfutwah AKW, Abernathy E, Demanou M. First report of the genomic characterization of rubella viruses circulating in Cameroon. J. Med. Virol. 2019 Jun;91(6):928-934.[↩]

- Dammeyer J. Congenital rubella syndrome and delayed manifestations. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010 Sep;74(9):1067-70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2010.06.007[↩][↩]

- Tyor W, Harrison T. Mumps and rubella. Handb Clin Neurol. 2014;123:591-600. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53488-0.00028-6[↩]

- Edwards MS. Rubella. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/rubella[↩][↩]

- Dontigny L, Arsenault MY, Martel MJ. No. 203-Rubella in Pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2018 Aug;40(8):e615-e621. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2018.05.009[↩]

- Riley LE. Rubella in pregnancy. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/rubella-in-pregnancy[↩][↩]

- Drutz JE. Rubella. Pediatr Rev. 2010 Mar;31(3):129-30; discussion 130. doi: 10.1542/pir.31-3-129[↩][↩]

- HPA Rash Guidance Working Group. Guidance on Viral Rash in Pregnancy. Investigation, Diagnosis and Management of Viral Rash Illness or Exposure to Viral Rash Illness in Pregnancy. London: Health Protection Agency, 2011.[↩][↩]

- Infectious Diseases in Pregnancy Screening Programme. Programme Standards. UK National Screening Committee, 2010.[↩]

- Recommandations en santé publique. Surveillance sérologique et prévention de la toxoplasmose et de la rubéole au cours de la grossesse. Haute Autorité de Santé, 2009.[↩]

- Infectious Diseases in Pregnancy Screening Programme. Handbook for laboratories. UK National Screening Committee, 2012.[↩]