Contents

- What is colon cancer

- What is a polyp in the colon?

- What is an adenoma (adenomatous polyp)?

- What are tubular adenomas, tubulovillous adenomas, and villous adenomas?

- What does it mean if I have an adenoma (adenomatous polyp), such as a sessile serrated adenoma or traditional serrated adenoma?

- What if my report mentions dysplasia?

- How does having an adenoma affect my future follow-up care?

- What if my adenoma was not completely removed?

- What if my report also mentions hyperplastic polyps?

- Colon cancer signs and symptoms

- Colon cancer causes

- Risk factors for colon cancer

- Colon cancer prevention

- Screening Tests for Colorectal Cancer

- People at increased or high risk

- Table 1. Professional society recommendations on when to start and when to stop colorectal cancer screening

- Table 2. American Cancer Society Guidelines on Screening and Surveillance for the Early Detection of Colorectal Adenomas and Cancer in People who have a history of polyps on prior colonoscopy

- Table 3. American Cancer Society Guidelines on Screening and Surveillance for the Early Detection of Colorectal Adenomas and Cancer in People who have had colorectal cancer

- Table 4. American Cancer Society Guidelines on Screening and Surveillance for the Early Detection of Colorectal Adenomas and Cancer in People with a family history of colorectal cancer or adenomatous polyps

- Table 5. American Cancer Society Guidelines on Screening and Surveillance for the Early Detection of Colorectal Adenomas and Cancer in People with familial adenomatous polyposis, Lynch syndrome & inflammatory bowel disease

- The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) colon cancer screening guidelines

- Tests that can find both colorectal polyps and cancer

- Stool-based tests that mainly find colorectal cancer

- Table 6. The pros and cons of colorectal cancer screening tests

- Colon cancer Diagnosis

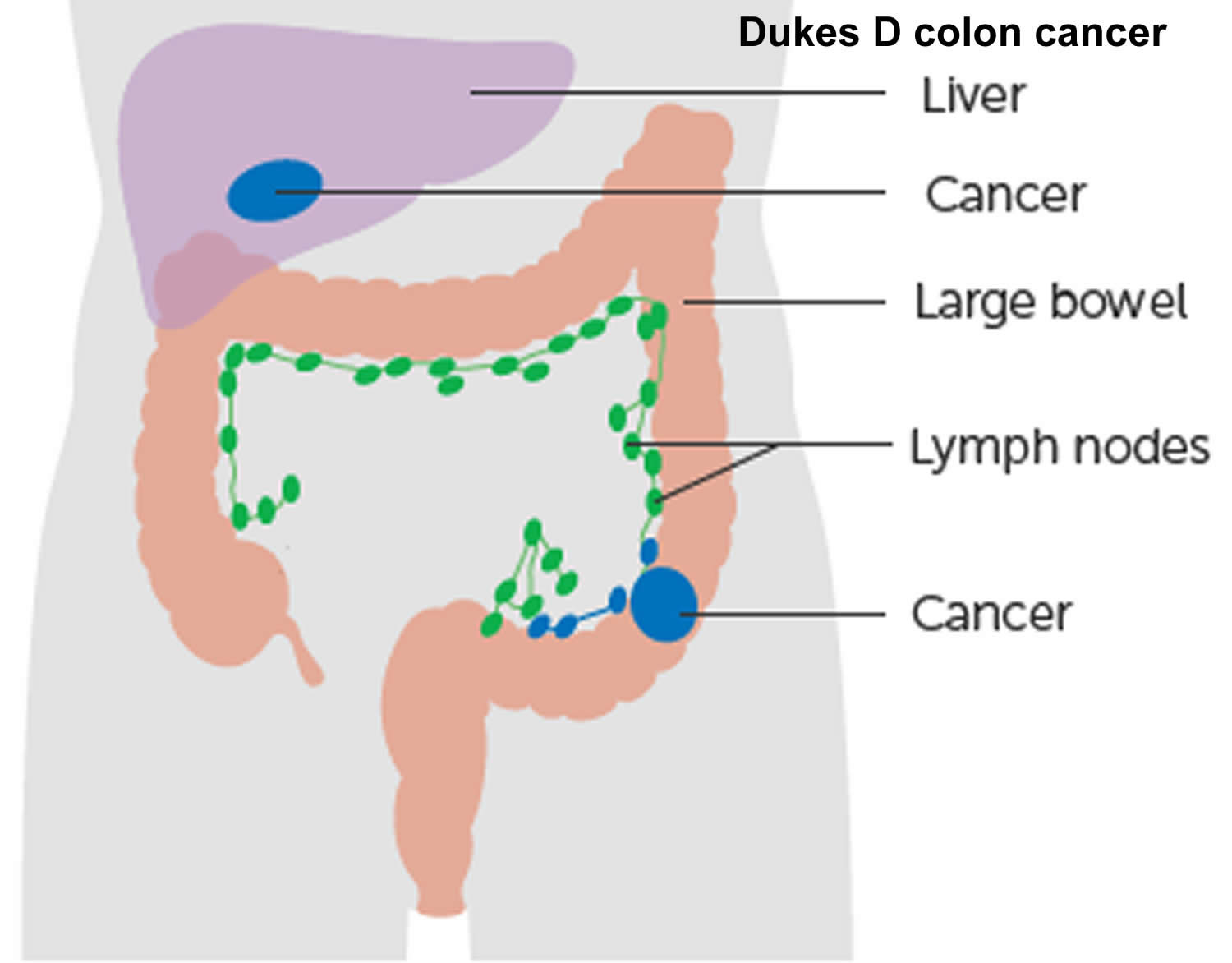

- Colon cancer stages

- Colon cancer survival rate

- Colon cancer treatment

- Colon cancer treatment by Stage

- Rectal cancer treatment by Stage

- Colon cancer prognosis

What is colon cancer

Colon cancer also known as bowel cancer or colorectal cancer (a term that combines colon cancer and rectal cancer which begins in the rectum), is cancer of the large intestine (colon or large bowel), which is the final part of your digestive tract. The colon (large bowel) is the main part of the large intestine and is about 5 feet long. The rectum and anal canal make up the last part of the large intestine and are about 6 to 8 inches long. The anal canal ends at the anus (the opening of the large intestine to the outside of the body). Cancer that begins in the colon is called colon cancer, and cancer that begins in the rectum is called rectal cancer. Cancer that starts in either of these organs may also be called colorectal cancer. Depending on where the cancer starts, colon cancer is sometimes called colon or rectal cancer or colorectal cancer. Colon cancer and rectal cancer are often grouped together because they have many features in common. The large intestine (colon) extends from the distal end of the ileum to the anus, a distance of approximately 1.5 m in adults (5 ft) long and 6.5 cm (2.5 in.) in diameter. Together, the rectum and anal canal make up the last part of the large intestine and are about 6-8 inches long. The anal canal ends at the anus (the opening of the large intestine to the outside of the body). Most cases of colon cancer begin as small, noncancerous (benign) clumps of cells called adenomatous polyps. Over time some of these polyps can become colon cancers. Polyps may be small and produce few, if any, symptoms. For this reason, doctors recommend regular screening tests to help prevent colon cancer by identifying and removing polyps before they turn into cancer.

The chance of changing into a cancer depends on the kind of polyp. The 2 main types of polyps are:

- Adenomatous polyps (adenomas): These polyps sometimes change into cancer. Because of this, adenomas are called a pre-cancerous condition.

- Hyperplastic polyps and inflammatory polyps: These polyps are more common, but in general they are not pre-cancerous.

Other polyp characteristics that can increase the chances a polyp may contain cancer or increase someone’s risk of developing colorectal cancer besides the type include the size (larger than 1 cm), the number found (more than two), and if dysplasia is seen in the polyp after it is removed.

Dysplasia, another pre-cancerous condition, is an area in a polyp or in the lining of the colon or rectum where the cells look abnormal (but not like true cancer cells).

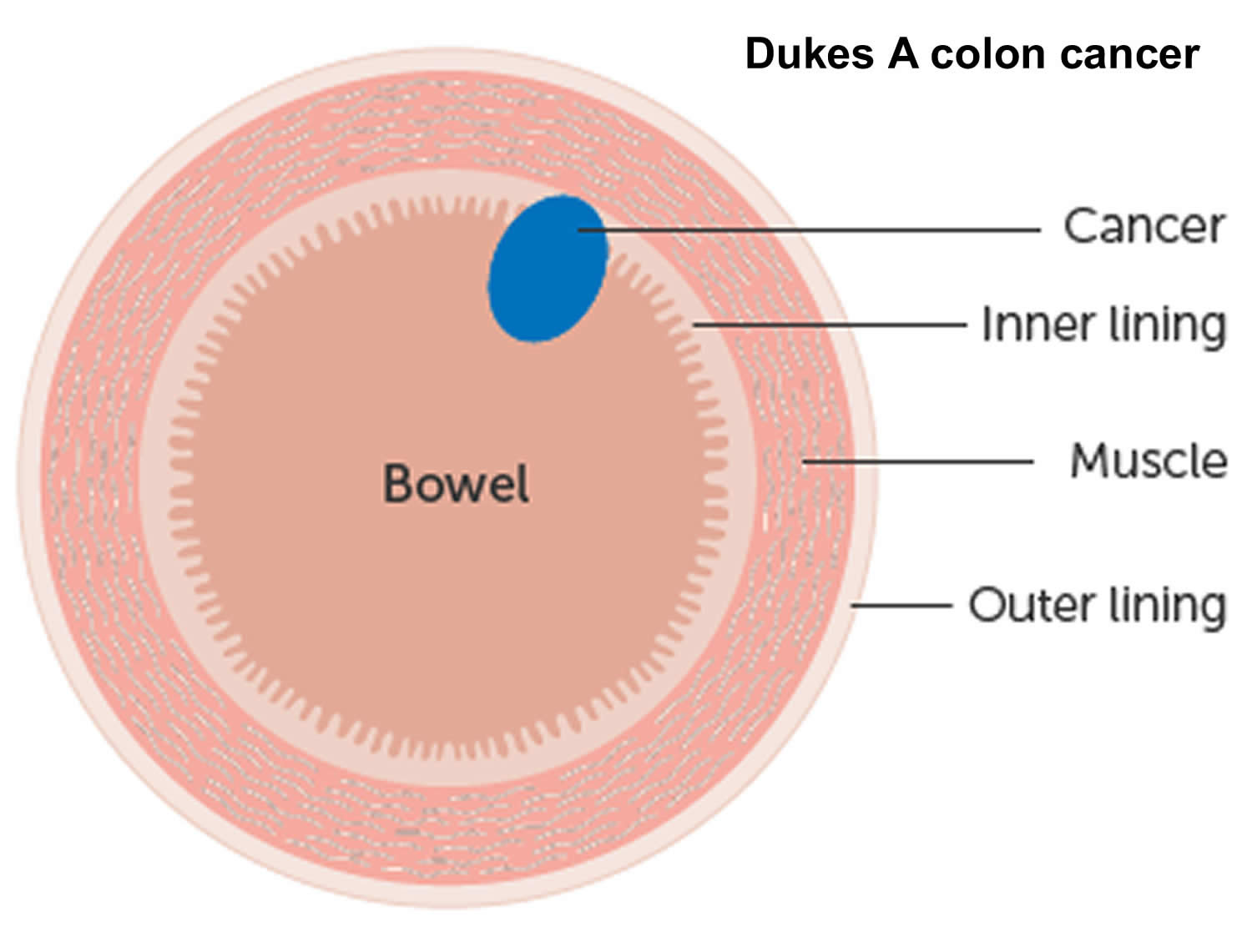

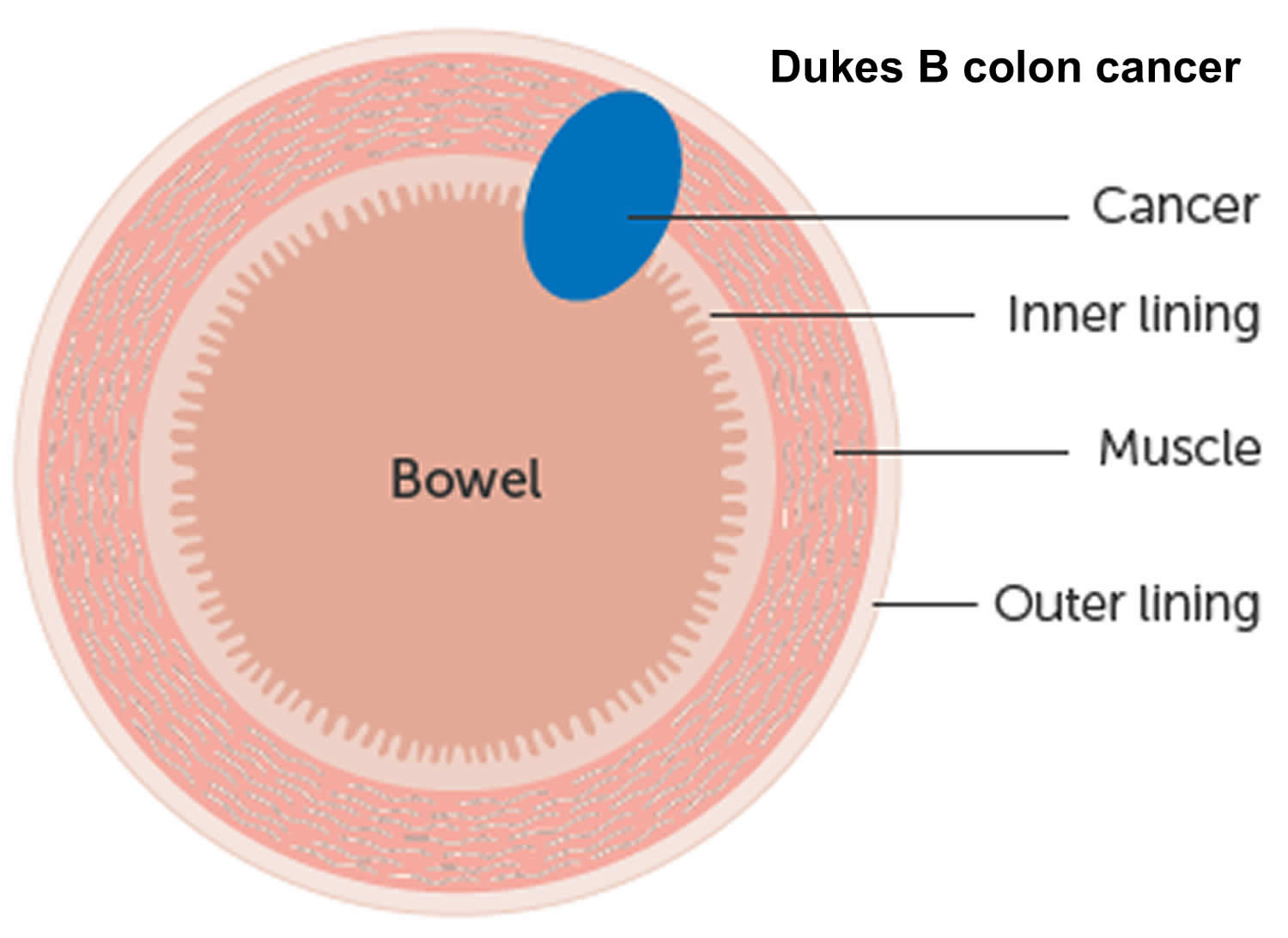

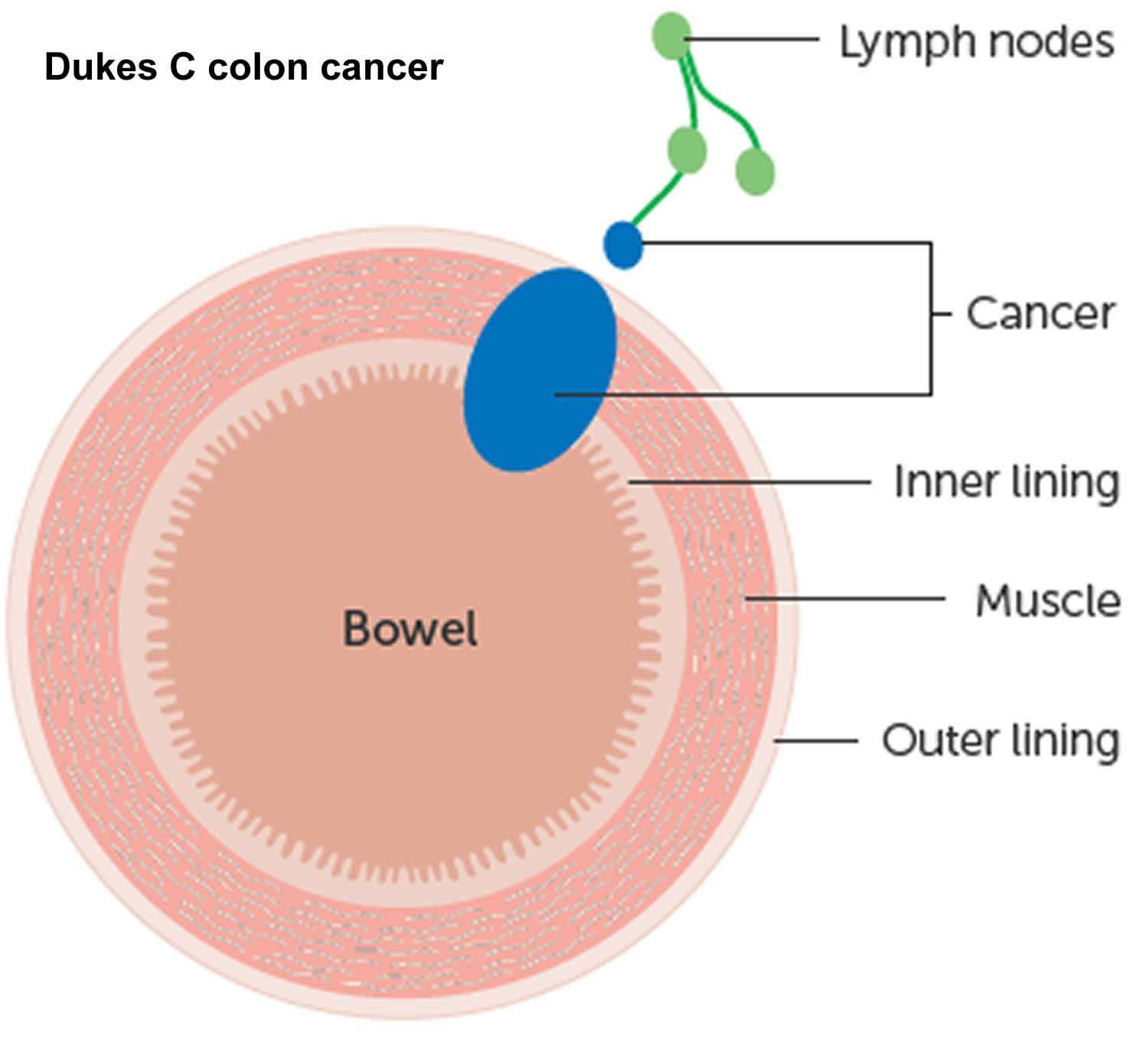

If cancer forms in a polyp, it can eventually begin to grow into the wall of the colon or rectum.

The wall of the colon and rectum is made up of several layers. Colorectal cancer starts in the innermost layer (the mucosa) and can grow outward through some or all of the other layers. When cancer cells are in the wall, they can then grow into blood vessels or lymph vessels (tiny channels that carry away waste and fluid). From there, they can travel to nearby lymph nodes or to distant parts of the body.

The stage (extent of spread) of a colorectal cancer depends on how deeply it grows into the wall and if it has spread outside the colon or rectum.

It can take as many as 10 to 15 years for a polyp to develop into colorectal cancer. Regular screening can often prevent colorectal cancer by finding and removing polyps before they have the chance to turn into cancer. Screening can also often find colorectal cancer early, when it might be easier to treat.

Excluding skin cancers, colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer diagnosed in both men and women in the United States. The American Cancer Society’s estimates for the number of colorectal cancer cases in the United States for 2025 are 1, 2:

- About 107,320 new cases of colon cancer (54,510 in men and 52,810 in women)

- About 46,950 new cases of rectal cancer (27,950 in men and 19,000 in women)

- The rate of people being diagnosed with colon or rectal cancer each year has dropped overall since the mid-1980s, mainly because more people are getting screened and changing their lifestyle-related risk factors. From 2012 to 2021, incidence rates dropped by about 1% each year. But this downward trend is mostly in older adults. In people younger than 50 years of age, rates have increased by 2.4% per year from 2012 to 2021.

- In the United States, colorectal cancer is the third-leading cause of cancer-related deaths in men and the fourth leading cause in women, but it’s the second most common cause of cancer deaths when numbers for men and women are combined. .

- Deaths: Colorectal cancer is expected to cause about 52,900 deaths during 2025 (colon and rectal cancers combined)

- Overall, the lifetime risk of developing colorectal cancer is about 1 in 24 for men (4.2%) and 1 in 26 (3.8%) for women. However, each person’s risk might be higher or lower than this, depending on their risk factors for colorectal cancer.

- About 4.2% of Americans are expected to develop colorectal cancer within their lifetime, and the lifetime risk of dying from colorectal cancer is 1.7% 3. Age-specific incidence and mortality rates show that most colorectal cancer cases are diagnosed after age 54 years and 78% of cases occur in patients aged 55 years and older; about 15% of colorectal cancer cases occur in patients aged 45 to 54 years 2, 4.

- Colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death in the United States. The death rate was 13.4 per 100,000 men and women per year based on 2015–2019 deaths, age-adjusted.

- Colorectal cancer represents 7.9% of all new cancer cases in the U.S.

- Colorectal cancer deaths represents 8.6% of all cancer deaths in the U.S.

- Rate of New Cases and Deaths per 100,000: The rate of new cases of colorectal cancer was 36.5 per 100,000 men and women per year. The death rate was 12.9 per 100,000 men and women per year. These rates are age-adjusted and based on 2017–2021 cases and 2018–2022 deaths.

- Lifetime Risk of Developing colorectal cancer: Approximately 4.0 percent of men and women will be diagnosed with colorectal cancer at some point during their lifetime, based on 2018–2021 data.

- In 2021, there were an estimated 1,392,445 people living with colorectal cancer in the United States.

- 5-Year Relative Survival is 65%. Relative survival is an estimate of the percentage of patients who would be expected to survive the effects of their cancer. It excludes the risk of dying from other causes. Because survival statistics are based on large groups of people, they cannot be used to predict exactly what will happen to an individual patient. No two patients are entirely alike, and treatment and responses to treatment can vary greatly.

Overall, the lifetime risk of developing colorectal cancer is about 1 in 24 (4.2%) for men and 1 in 26 (3.8%) for women. This risk is slightly lower in women than in men. A number of other factors (described in Colorectal Cancer Risk Factors) can also affect your risk for developing colorectal cancer.

Colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death when numbers for both men and women are combined. The death rate (the number of deaths per 100,000 people per year) from colorectal cancer has been dropping in older adults for several decades. It is expected to cause about 52,900 deaths during 2025. One reason for this is that colorectal polyps are now more often found by screening and removed before they can develop into cancers. Screening also results in many colorectal cancers being found earlier, when they are likely to be easier to treat. In addition, treatments for colorectal cancer have improved over the last few decades. In people under 55, however, death rates have been increasing about 1% per year since the mid-2000s.

When colorectal cancer is found at an early stage before it has spread, the 5-year relative survival rate is about 90%. But only about 4 out of 10 colorectal cancers are found at this early stage. When cancer has spread outside the colon or rectum, survival rates are lower.

Unfortunately, only a little more than half of people who should get tested for colorectal cancer get the tests that they should. This may be due to things like lack of public and health care provider awareness of screening options, costs, and health insurance coverage issues.

Cancer of the colon is a highly treatable and often curable disease when localized to the bowel. Surgery is the primary form of treatment and results in cure in approximately 50% of the patients. Recurrence following surgery is a major problem and is often the ultimate cause of death.

The colon and rectum anatomy

To understand colorectal cancer, it helps to know about the normal structure and function of the colon and rectum.

The colon and rectum make up the large intestine (or large bowel), which is part of the digestive system, also called the gastrointestinal (GI) system (see Figure 1 below). The digestive tract includes the mouth, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine, and rectum. The large intestine is approximately 5 feet (1.5 meters) long, making up one-fifth of the length of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract 5. The large intestine is responsible for processing indigestible food material (chyme) after most nutrients are absorbed in the small intestine. The large intestine performs an essential role by absorbing water, vitamins, and electrolytes from waste material 6, 7.

The large intestine is composed of 4 parts. It includes the cecum and ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, and sigmoid colon. The parts of the colon are named by which way the food is traveling through them.

- The first section is called the ascending colon. It starts with a pouch called the cecum, where undigested food is comes in from the small intestine. It continues upward on the right side of the abdomen (belly).

- The second section is called the transverse colon. It goes across the body from the right to the left side.

- The third section is called the descending colon because it descends (travels down) on the left side.

- The fourth section is called the sigmoid colon because of its “S” shape. The sigmoid colon joins the rectum, which then connects to the anus.

The ascending and transverse colon together are called the proximal colon. The descending and sigmoid colon are called the distal colon.

Figure 1. Gastrointestinal tract (human digestive system)

Figure 2. Large intestine (colon)

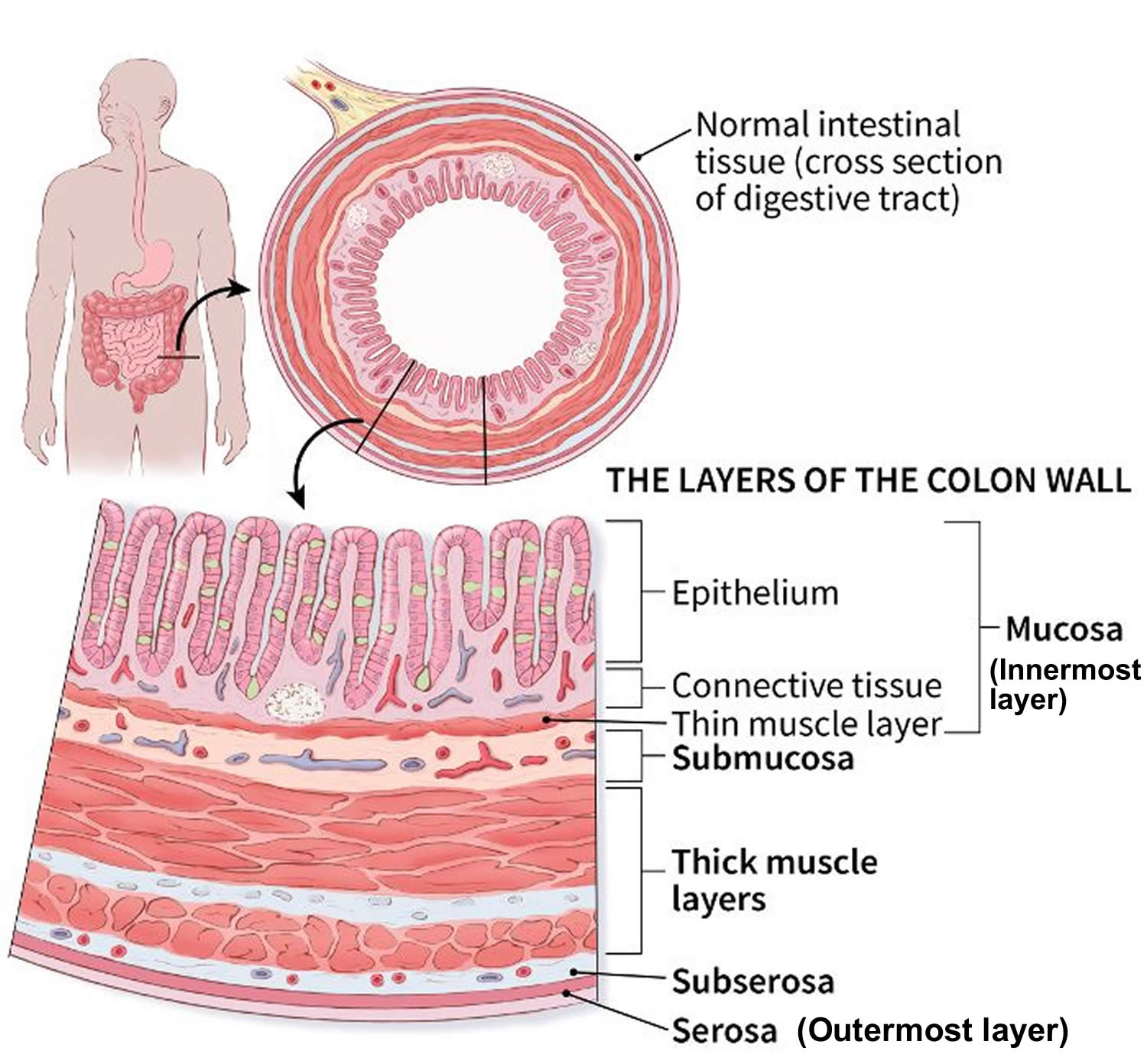

The intestinal wall

The intestinal wall is made up of multiple layers. The 4 layers of the large intestine from the lumen outward are the mucosa, submucosa, muscular layer, and serosa (Figure 2). The muscular layer is made up of 2 layers of smooth muscle, the inner, circular layer, and the outer, longitudinal layer.

Figure 3. Large intestine wall layers

Figure 4. Large intestine anatomy (normal)

What is a polyp in the colon?

A polyp is a projection (growth) of tissue from the inner lining of the colon into the lumen (hollow center) of the colon. Different types of polyps look different under the microscope. Polyps are benign (non-cancerous) growths, but cancer can start in some types of polyps. These polyps can be thought of as pre-cancers, which is why it is important to have them removed.

Polyps that tend to grow as slightly flattened, broad-based polyps are referred to as sessile.

Serrated polyps (serrated adenomas) have a saw-tooth appearance under the microscope. There are 2 types, which look a little different under the microscope:

- Sessile serrated adenomas (also called sessile serrated polyps)

- Traditional serrated adenomas

Both types need to be removed from your colon.

What is an adenoma (adenomatous polyp)?

An adenoma is a polyp made up of tissue that looks much like the normal lining of your colon, although it is different in several important ways when it is looked at under the microscope. In some cases, a cancer can start in the adenoma.

What are tubular adenomas, tubulovillous adenomas, and villous adenomas?

Adenomas can have several different growth patterns that can be seen under the microscope by the pathologist. There are 2 major growth patterns: tubular and villous. Many adenomas have a mixture of both growth patterns, and are called tubulovillous adenomas. Most adenomas that are small (less than ½ inch) have a tubular growth pattern. Larger adenomas may have a villous growth pattern. Larger adenomas more often have cancers developing in them. Adenomas with a villous growth pattern are also more likely to have cancers develop in them.

The most important thing is that your polyp has been completely removed and does not show cancer. The growth pattern is only important because it helps determine when you will need your next colonoscopy to make sure you don’t develop colon cancer in the future.

What does it mean if I have an adenoma (adenomatous polyp), such as a sessile serrated adenoma or traditional serrated adenoma?

These types of polyps are not cancer, but they are pre-cancerous (meaning that they can turn into cancers). Someone who has had one of these types of polyps has an increased risk of later developing cancer of the colon. Most patients with these polyps, however, never develop colon cancer.

What if my report mentions dysplasia?

Dysplasia is a term that describes how much your polyp looks like cancer under the microscope:

- Polyps that are only mildly abnormal (don’t look much like cancer) are said to have low-grade (mild or moderate) dysplasia.

- Polyps that are more abnormal and look more like cancer are said to have high-grade (severe) dysplasia.

The most important thing is that your polyp has been completely removed and does not show cancer. If high-grade dysplasia is found in your polyp, it might mean you need to have a repeat (follow-up) colonoscopy sooner than if high-grade dysplasia wasn’t found, but otherwise you do not need to worry about dysplasia in your polyp.

How does having an adenoma affect my future follow-up care?

Since you had an adenoma, you will need to have another colonoscopy to make sure that you don’t develop any more adenomas. When your next colonoscopy should be scheduled depends on a number of things, like how many adenomas were found, if any were villous, and if any had high-grade dysplasia. The timing of your next colonoscopy should be discussed with your treating doctor, as he or she knows the details of your specific case.

What if my adenoma was not completely removed?

If your adenoma was biopsied but not completely removed, you will need to talk to your doctor about what other treatment you’ll need. Most of the time, adenomas are removed during a colonoscopy. Sometimes, though, the adenoma may be too large to remove during colonoscopy. In such cases you may need surgery to have the adenoma removed.

What if my report also mentions hyperplastic polyps?

Hyperplastic polyps are typically benign (they aren’t pre-cancers or cancers) and are not a cause for concern.

Colon cancer signs and symptoms

Many people with colon cancer experience no symptoms in the early stages of the disease. When symptoms appear, they’ll likely vary, depending on the cancer’s size and location in your large intestine. Many of the symptoms of colon cancer can also be caused by something that isn’t cancer, such as infection, hemorrhoids, irritable bowel syndrome, or inflammatory bowel disease.

Colorectal cancer might not cause symptoms right away, but if it does, it may cause one or more of these symptoms:

- A change in bowel habits, such as diarrhea, constipation, or narrowing of the stool, that lasts for more than a few days

- A feeling that you need to have a bowel movement that’s not relieved by having one

- Rectal bleeding with bright red blood

- Blood in the stool, which might make the stool look dark brown or black

- Persistent abdominal discomfort, such as cramps, gas or pain

- A feeling that your bowel doesn’t empty completely

- Weakness or fatigue

- Unexplained weight loss

Signs of colon cancer include blood in the stool or a change in bowel habits.

These and other signs and symptoms may be caused by colon cancer or by other conditions. Check with your doctor if you have any of the following:

- A change in bowel habits.

- Blood (either bright red or very dark) in the stool.

- Diarrhea, constipation, or feeling that the bowel does not empty all the way.

- Stools that are narrower than usual.

- Frequent gas pains, bloating, fullness, or cramps.

- Weight loss for no known reason.

- Feeling very tired.

- Vomiting.

Colorectal cancers can often bleed into the digestive tract. Sometimes the blood can be seen in the stool or make it look darker, but often the stool looks normal. But over time, the blood loss can build up and can lead to low red blood cell counts (anemia). Sometimes the first sign of colorectal cancer is a blood test showing a low red blood cell count.

Some people may have signs that the cancer has spread to the liver with a large liver felt on exam, jaundice (yellowing of the skin or whites of the eyes), or trouble breathing from cancer spread to the lungs.

Many of these symptoms can be caused by conditions other than colorectal cancer, such as infection, hemorrhoids, or irritable bowel syndrome. Still, if you have any of these problems, it’s important to see your doctor right away so the cause can be found and treated, if needed.

If you notice any persistent symptoms that worry you, make an appointment with your doctor.

Talk with your doctor about when to begin colon cancer screening. Guidelines generally recommend that colon cancer screenings begin around 50. Your doctor may recommend more frequent or earlier screening if you have other risk factors, such as a family history of the disease.

Colon cancer causes

In most cases, it’s not clear what causes colon cancer. Doctors know that colon cancer occurs when healthy cells in the colon develop errors in their genetic blueprint, the DNA. A cell’s DNA contains a set of instructions that tell a cell what to do.

Healthy cells grow and divide in an orderly way to keep your body functioning normally. But when a cell’s DNA is damaged and becomes cancerous, cells continue to divide — even when new cells aren’t needed. As the cells accumulate, they form a tumor.

With time, the cancer cells can grow to invade and destroy normal tissue nearby. And cancerous cells can travel to other parts of the body to form deposits there (metastasis).

Inherited gene mutations that increase the risk of colon cancer

Inherited gene mutations that increase the risk of colon cancer can be passed through families, but these inherited genes are linked to only a small percentage of colon cancers. Inherited gene mutations don’t make cancer inevitable, but they can increase an individual’s risk of cancer significantly.

The most common forms of inherited colon cancer syndromes are:

- Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) also called Lynch syndrome. Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer increases the risk of colon cancer and other cancers. People with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer tend to develop colon cancer before age 50. Lynch syndrome (hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer or HNPCC) is caused by changes in genes that normally help a cell repair damaged DNA. A mutation in one of the DNA repair genes like MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, and EPCAM, can allow DNA errors to go unfixed. These errors will sometimes affect growth-regulating genes, which may lead to the development of cancer.

- Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP). About 1% of all colorectal cancers are caused by familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP). Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) is caused by inherited changes in the APC gene. The APC gene is a tumor suppressor gene; it normally helps keep cell growth in check. In people with inherited changes in the APC gene, this “brake” on cell growth is turned off, causing hundreds of polyps to form in the colon. Over time, cancer will nearly always develop in one or more of these polyps. Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) is a rare disorder that causes you to develop thousands of polyps in the lining of your colon and rectum. In the most common type of FAP, hundreds or thousands of polyps develop in a person’s colon and rectum, often starting at ages 10 to 12 years. Cancer usually develops in 1 or more of these polyps as early as age 20. By age 40, almost all people with FAP will have colon cancer if their colon hasn’t been removed to prevent it. People with FAP also have an increased risk for cancers of the stomach, small intestines, pancreas, liver, and some other organs. There are 3 sub-types of familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP):

- In attenuated FAP (AFAP), patients have fewer polyps (less than 100), and colorectal cancer tends to occur at a later age (40s and 50s).

- Gardner syndrome is a type of FAP that also causes non-cancer tumors of the skin, soft tissue, and bones.

- Turcot syndrome is a rare inherited condition in which people have a higher risk of many adenomatous polyps and colorectal cancer. People with Turcot syndrome who have the APC gene are also at risk of a specific type of brain cancer called medulloblastoma.

- Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is caused by inherited changes in the STK11 (LKB1) gene, a tumor suppressor gene. People with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome tend to have freckles around the mouth (and sometimes on their hands and feet) and a special type of polyp called hamartomas in their digestive tracts. These people are at a much higher risk for colorectal cancer, as well as other cancers, such as breast, ovary, and pancreas. They usually are diagnosed at a younger than usual age.

- MUTYH-associated polyposis (MAP) is caused by mutations in the MUTYH gene, which is involved in how the cell “proofreads” or checks the DNA and fixes errors when cells divide. People with MUTYH-associated polyposis (MAP) develop many colon polyps. These will almost always become cancer if not watched closely with regular colonoscopies. These people also have an increased risk of other cancers of the GI (gastrointestinal) tract and thyroid.

Familial adenomatous polyposis, hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer and other, rarer inherited colon cancer syndromes can be detected through genetic testing. If you’re concerned about your family’s history of colon cancer, talk to your doctor about whether your family history suggests you have a risk of these conditions. You may want to ask your doctor about genetic counseling and genetic testing.

Association between diet and increased colon cancer risk

Studies of large groups of people have shown an association between a typical Western diet and an increased risk of colon cancer. A typical Western diet is high in fat and low in fiber.

A diet that’s high in red meats (such as beef, pork, lamb, or liver) and processed meats (like hot dogs and some luncheon meats) raises your colorectal cancer risk.

Cooking meats at very high temperatures (frying, broiling, or grilling) creates chemicals that might raise your cancer risk. It’s not clear how much this might increase your colorectal cancer risk.

Having a low blood level of vitamin D may also increase your risk.

When people move from areas where the typical diet is low in fat and high in fiber to areas where the typical Western diet is most common, the risk of colon cancer in these people increases significantly. It’s not clear why this occurs, but researchers are studying whether a high-fat, low-fiber diet affects the microbes that live in the colon or causes underlying inflammation that may contribute to cancer risk. This is an area of active investigation and research is ongoing.

Following a healthy eating pattern that includes plenty of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, and that limits or avoids red and processed meats and sugary drinks probably lowers risk.

Risk factors for colon cancer

Anything that increases your chance of getting a disease is called a risk factor. Having a risk factor does not mean that you will get cancer; not having risk factors doesn’t mean that you will not get cancer. Talk to your doctor if you think you may be at risk for colorectal cancer.

Factors that may increase your risk of colon cancer include:

- Older age. The great majority of people diagnosed with colon cancer are older than 50. Colon cancer can occur in younger people, but it occurs much less frequently.

- African-American race. African-Americans have a greater risk of colon cancer than do people of other races in the US.

- Jews of Eastern European descent (Ashkenazi Jews) have one of the highest colorectal cancer risks of any ethnic group in the world.

- Having a personal history of cancer of the colon, rectum, or ovary.

- Having a personal history of high-risk adenomas (colorectal polyps that are 1 centimeter or larger in size or that have cells that look abnormal under a microscope).

- Having a personal history of inflammatory intestinal conditions for 8 years or more. Chronic inflammatory diseases of the colon, such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, can increase your risk of colon cancer.

- Having inherited syndromes that increase colon cancer risk. Genetic syndromes passed through generations of your family can increase your risk of colon cancer. These syndromes include familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer, which is also known as Lynch syndrome.

- Family history of colon or rectal cancer. You’re more likely to develop colon cancer if you have a parent, sibling or child with the disease (first-degree relative). If more than one family member has colon cancer or rectal cancer, your risk is even greater.

- Low-fiber, high-fat diet. Colon cancer and rectal cancer may be associated with a diet low in fiber and high in fat and calories. Research in this area has had mixed results. Some studies have found an increased risk of colon cancer in people who eat diets high in red meat and processed meat.

- A sedentary lifestyle. If you’re inactive, you’re more likely to develop colon cancer. Getting regular physical activity may reduce your risk of colon cancer.

- Diabetes. People with diabetes and insulin resistance have an increased risk of colon cancer. Both type 2 diabetes and colorectal cancer share some of the same risk factors (such as being overweight and physical inactivity). But even after taking these factors into account, people with type 2 diabetes still have an increased risk. They also tend to have a less favorable prognosis (outlook) after diagnosis.

- Obesity. People who are obese have an increased risk of colon cancer and an increased risk of dying of colon cancer when compared with people considered normal weight.

- Smoking. People who smoke may have an increased risk of colon cancer.

- Alcohol. Having three or more alcoholic drinks per day increases your risk of colon cancer.

- Radiation therapy for cancer. Radiation therapy directed at the abdomen to treat previous cancers increases the risk of colon and rectal cancer.

Colon cancer prevention

Get screened for colon cancer

People with an average risk of colon cancer can consider screening beginning at age 50. The American Cancer Society recommends that people at average risk of colorectal cancer start regular screening at age 45 8. But people with an increased risk, such as those with a family history of colon cancer, should consider screening sooner.

People who are in good health and with a life expectancy of more than 10 years should continue regular colorectal cancer screening through the age of 75.

For people ages 76 through 85, the decision to be screened should be based on a person’s preferences, life expectancy, overall health, and prior screening history.

People over 85 should no longer get colorectal cancer screening.

*For screening, people are considered to be at average risk if they do NOT have:

- A personal history of colorectal cancer or certain types of polyps

- A family history of colorectal cancer

- A personal history of inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease)

- A confirmed or suspected hereditary colorectal cancer syndrome, such as familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) or Lynch syndrome (hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer or HNPCC)

- A personal history of getting radiation to the abdomen (belly) or pelvic area to treat a prior cancer

Several screening options exist — each with its own benefits and drawbacks. Talk about your options with your doctor, and together you can decide which tests are appropriate for you. The most important thing is to get screened, no matter which test you choose.

Several screening tests can be divided into 2 main groups:

- Stool-based tests: These tests check the stool (feces) for signs of cancer. These tests are less invasive and easier to have done, but they need to be done more often.

- Visual (structural) exams: These tests look at the structure of the colon and rectum for any abnormal areas. This is done either with a scope (a tube-like instrument with a light and tiny video camera on the end) put into the rectum, or with special imaging (x-ray) tests.

These tests each have different risks and benefits (see below), and some of them might be better options for you than others.

Make lifestyle changes to reduce your risk

You can take steps to reduce your risk of colon cancer by making changes in your everyday life. Take steps to:

- Eat a variety of fruits, vegetables and whole grains. Fruits, vegetables and whole grains contain vitamins, minerals, fiber and antioxidants, which may play a role in cancer prevention. Choose a variety of fruits and vegetables so that you get an array of vitamins and nutrients.

- Drink alcohol in moderation, if at all. If you choose to drink alcohol, limit the amount of alcohol you drink to no more than one drink a day for women and two for men.

- Stop smoking. Talk to your doctor about ways to quit that may work for you.

- Exercise most days of the week. Try to get at least 30 minutes of exercise on most days. If you’ve been inactive, start slowly and build up gradually to 30 minutes. Also, talk to your doctor before starting any exercise program.

- Maintain a healthy weight. If you are at a healthy weight, work to maintain your weight by combining a healthy diet with daily exercise. If you need to lose weight, ask your doctor about healthy ways to achieve your goal. Aim to lose weight slowly by increasing the amount of exercise you get and reducing the number of calories you eat.

Colon cancer prevention for people with a high risk

Some medications have been found to reduce the risk of precancerous polyps or colon cancer. However, not enough evidence exists to recommend these medications to people who have an average risk of colon cancer. These options are generally reserved for people with a high risk of colon cancer.

For instance, some evidence links a reduced risk of polyps and colon cancer to regular use of aspirin or aspirin-like drugs. But it’s not clear what dose and what length of time would be needed to reduce the risk of colon cancer. Taking aspirin daily has some risks, including gastrointestinal bleeding and ulcers, so doctors typically don’t recommend this as a prevention strategy unless you have an increased risk of colon cancer.

Screening Tests for Colorectal Cancer

Doctors recommend certain screening tests for healthy people with no signs or symptoms in order to look for early colon cancer. Finding colon cancer at its earliest stage provides the greatest chance for a cure. Screening (which is a process of looking for cancer in people who have no symptoms) has been shown to reduce your risk of dying of colon cancer.

People with an average risk of colon cancer can consider screening beginning at age 45. But people with an increased risk, such as those with a family history of colon cancer, should consider screening sooner. African-Americans and American Indians may consider beginning colon cancer screening at age 45.

Both men and women should have a colon cancer screening test starting at age 45 (if following the American Cancer Society Guideline). Some doctors recommend that African Americans begin screening at age 45.

With a recent increase in colon cancer in people in their 40s, the American Cancer Society recommends that healthy men and women start screening at age 45. Talk to your doctor if you’re concerned.

Several screening options exist — each with its own benefits and drawbacks. Talk about your options with your doctor, and together you can decide which tests are appropriate for you. If a colonoscopy is used for screening, polyps can be removed during the procedure before they turn into cancer.

There are 3 main types of colorectal cancer screening tests 9:

- Blood-based tests: These tests check a person’s blood for signs of colorectal cancer.

- Stool-based tests: These tests check the stool (feces) for signs of colon cancer. These tests are less invasive and easier to have done, but they need to be done more often.

- Visual (structural) exams: These tests look at the structure of the colon and rectum for any abnormal areas. They are done either with a scope (a tube-like instrument with a light and tiny video camera on the end) put into the rectum, or with special imaging (x-ray) tests.

These tests each have different risks and benefits and some of them might be better options for you than others.

If you choose to be screened with a test other than colonoscopy, any abnormal test result should be followed up with a timely colonoscopy.

Some of these tests might also be used if you have symptoms of colorectal cancer or other digestive diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease.

The American Cancer Society believes that preventing colorectal cancer (and not just finding it early) should be a major reason for getting tested. Having polyps found and removed keeps some people from getting colorectal cancer. You are encouraged to have tests that have the best chance of finding both polyps and cancer if these tests are available to you and you are willing to have them. But the most important thing is to get tested, no matter which test you choose.

For screening, people are considered to be at AVERAGE risk if they DO NOT have:

- A personal history of colorectal cancer or certain types of polyps

- A family history of colorectal cancer

- A personal history of inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease)

- A confirmed or suspected hereditary colorectal cancer syndrome, such as familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) or Lynch syndrome (hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer or HNPCC)

- A personal history of getting radiation to the abdomen (belly) or pelvic area to treat a prior cancer

People who are in good health and with a life expectancy of more than 10 years should continue regular colorectal cancer screening through the age of 75.

For people ages 76 through 85, the decision to be screened should be based on a person’s preferences, life expectancy, overall health, and prior screening history.

People over 85 should no longer get colorectal cancer screening.

When colon cancer is found early, before it has spread, the 5-year relative survival rate is 90%. This means 9 out of 10 people with early-stage cancer survive at least 5 years. But if the cancer has had a chance to spread outside the colon, survival rates are lower.

Starting at age 45, men and women at average risk for developing colorectal cancer should use one of the screening tests below:

Screening is the process of looking for cancer in people who have no symptoms. Several tests can be used to screen for colorectal cancers. These tests can be divided into 8:

Visual (structural) exams of the colon and rectum

- Colonoscopy every 10 years

- CT colonography (virtual colonoscopy) every 5 years

- Sigmoidoscopy every 5 years

Stool-based tests

- Highly sensitive fecal immunochemical test (FIT) every year

- Highly sensitive guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (gFOBT) every year

- Multi-targeted stool DNA test with fecal immunochemical testing (MT-sDNA or sDNA-FIT or FIT-DNA)) every 3 years

Tests that can find both colorectal polyps and cancer are encouraged if they are available and you are willing to have them. But the most important thing is to get tested, no matter which test you choose.

These tests, as well as others, can also be used when people have symptoms of colorectal cancer and other digestive diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease.

People at increased or high risk

If you are at an increased or high risk of colorectal cancer, you might need to start colorectal cancer screening before age 45 and/or be screened more often. The following conditions make your risk higher than average:

- A personal history of colorectal cancer or adenomatous polyps

- A personal history of inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease)

- A personal history of radiation to the abdomen (belly) or pelvic area to treat a prior cancer

- A strong family history of colorectal cancer or polyps

- A known family history of a hereditary colorectal cancer syndrome such as familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) or Lynch syndrome (hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer or HNPCC)

The tables below suggest screening guidelines for people with increased or high risk of colorectal cancer based on specific risk factors. Some people may have more than one risk factor. Refer to the tables below and discuss these recommendations with your doctor. Your doctor can suggest the best screening option for you, as well as any changes in the schedule based on your individual risk.

People at increased risk for colorectal cancer

- People with one or more family members who have had colon or rectal cancer. Screening recommendations for these people depend on who in the family had cancer and how old they were when it was diagnosed. Some people with a family history will be able to follow the recommendations for average risk adults, but others might need to get a colonoscopy (and not any other type of test) more often, and possibly starting before age 45.

- People who have had certain types of polyps removed during a colonoscopy. Most of these people will need to get a colonoscopy again after 3 years, but some people might need to get one earlier (or later) than 3 years, depending on the type, size, and number of polyps.

- People who have had colon or rectal cancer. Most of these people will need to start having colonoscopies regularly about one year after surgery to remove the cancer. Other procedures like MRI or proctoscopy with ultrasound might also be recommended for some people with rectal cancer, depending on the type of surgery they had.

- People who have had radiation to the abdomen (belly) or pelvic area to treat a prior cancer. Most of these people will need to start having colorectal screening (colonoscopy or stool based testing) at an earlier age (depending on how old they were when they got the radiation). Screening often begins 5 years after the radiation was given or at age 30, whichever comes last. These people might also need to be screened more often than normal (such as at least every 3 to 5 years).

People at high risk for colorectal cancer

- People with inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis). These people generally need to get colonoscopies (not any other type of test) starting at least 8 years after they are diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease. Follow-up colonoscopies should be done every 1 to 3 years, depending on the person’s risk factors for colorectal cancer and the findings on the previous colonoscopy.

- People known or suspected to have certain genetic syndromes. These people generally need to have colonoscopy (not any of the other tests). Screening is often recommended to begin at a young age, possibly as early as the teenage years for some syndromes – and needs to be done much more frequently. Specifics depend on which genetic syndrome you have, and other factors. If you’re at increased or high risk of colorectal cancer (or think you might be), talk to your doctor to learn more. Your doctor can suggest the best screening option for you, as well as determine what type of screening schedule you should follow, based on your individual risk.

Note: As of 2022, the American Cancer Society no longer have screening guidelines specifically for people at increased or high risk of colorectal cancer. The tables below were from American Cancer Society prior to them removing their screening guidelines for people at increased or high risk of colorectal cancer. But we have decided to leave them here for your reference.

Table 1. Professional society recommendations on when to start and when to stop colorectal cancer screening

| Colorectal cancer screening start age | Colorectal cancer screening stop age | |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-Society Task Force, 2021 | “We suggest that clinicians offer colorectal cancer screening to all average-risk individuals age 45-49 (weak recommendation; low-quality evidence).” | “We suggest that individuals who are up to date with screening and have negative prior screening tests, particularly high-quality colonoscopy, consider stopping screening at age 75 years or when life expectancy is less than 10 years (weak recommendation, low-quality evidence).” |

| “For average-risk individuals who have not initiated screening before age 50, we recommend that clinicians offer colorectal cancer screening to all average-risk individuals beginning at age 50 (strong recommendation, high-quality evidence).” | “We suggest that persons without prior screening should be considered for screening up to age 85, depending on consideration of their age and comorbidities (weak recommendation, low-quality evidence).” | |

| National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2021 10 | “Average risk: age ≥45. The panel has reviewed existing data for beginning screening of average-risk individuals at age <50 years. Based on their assessment, the panel agrees that the data are stronger to support beginning screening at 50 years but acknowledges that lower-level evidence supports a benefit for screening earlier. When initiating screening for all eligible individuals, the panel recommends a discussion of potential harms/risks and benefits, and the consideration of all recommended colorectal cancer screening options.” | Not provided |

| American College of Gastroenterology, 2021 11 | “We recommend colorectal cancer screening in average-risk individuals between ages 50 and 75 years to reduce incidence of advanced adenoma, colorectal cancer, and mortality from colorectal cancer.” Strong recommendation; moderate-quality evidence “We suggest colorectal cancer screening in average-risk individuals between ages 45 and 49 years to reduce incidence of advanced adenoma, colorectal cancer, and mortality from colorectal cancer.” Conditional recommendation; very low-quality evidence | “We suggest that a decision to continue screening beyond age 75 years be individualized (conditional recommendation strength, very low-Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation quality of evidence).” |

| U.S. Preventative Services Task Force, 2021 12 | Grade A: “The U.S. Preventative Services Task Force recommends screening for colorectal cancer in all adults ages 50 to 75 years.” Grade B: “The U.S. Preventative Services Task Force recommends screening for colorectal cancer in adults aged 45 to 49 years.” | Grade C: “The U.S. Preventative Services Task Force recommends that clinicians selectively offer screening for colorectal cancer in adults aged 76 to 85 years. Evidence indicates that the net benefit of screening all persons in this age group is small. In determining whether this service is appropriate in individual cases, patients and clinicians should consider the patient’s overall health, prior screening history, and preferences.” |

| American College of Physicians, 2019 13 | “Clinicians should screen for colorectal cancer in average-risk adults between the ages of 50 and 75 years.” | “Clinicians should discontinue screening for colorectal cancer in average-risk adults older than 75 years or in adults with a life expectancy of 10 years or less.” |

| American Cancer Society, 2018 14 | “The American Cancer Society recommends that adults aged 45 and older with an average risk of colorectal cancer undergo regular screening with either a high-sensitivity stool-based test or a structural (visual) examination, depending on patient preference and test availability. As a part of the screening process, all positive results on non-colonoscopy screening tests should be followed up with timely colonoscopy.” | “Average-risk adults in good health with a life expectancy of greater than 10 years continue colorectal cancer screening through the age of 75 years (qualified recommendation).” |

| “The recommendation to begin screening at age 45 is a qualified recommendation.” | Clinicians should “individualize colorectal cancer screening decisions for individuals aged 76 through 85 years based on patient preferences, life expectancy, health status, and prior screening history (qualified recommendation).” | |

| “The recommendation for regular screening in adults aged 50 y and older is a strong recommendation.” | Clinicians should “discourage individuals over age 85 years from continuing colorectal cancer screening (qualified recommendation).” |

Table 2. American Cancer Society Guidelines on Screening and Surveillance for the Early Detection of Colorectal Adenomas and Cancer in People who have a history of polyps on prior colonoscopy

| INCREASED RISK – People who have a history of polyps on prior colonoscopy | |||

| Risk category | When to test | Recommended test(s) | Comment |

| People with small rectal hyperplastic polyps | Same age as those at average risk | Colonoscopy, or other screening options at same intervals as for those at average risk | Those with hyperplastic polyposis syndrome are at increased risk for adenomatous polyps and cancer and should have more intensive follow-up. |

| People with 1 or 2 small (no more than 1 cm) tubular adenomas with low-grade dysplasia | 5 to 10 years after the polyps are removed | Colonoscopy | Time between tests should be based on other factors such as prior colonoscopy findings, family history, and patient and doctor preferences. |

| People with 3 to 10 adenomas, or a large (at least 1 cm) adenoma, or any adenomas with high-grade dysplasia or villous features | 3 years after the polyps are removed | Colonoscopy | Adenomas must have been completely removed. If colonoscopy is normal or shows only 1 or 2 small tubular adenomas with low-grade dysplasia, future colonoscopies can be done every 5 years. |

| People with more than 10 adenomas on a single exam | Within 3 years after the polyps are removed | Colonoscopy | Doctor should consider possible genetic syndrome (such as FAP or Lynch syndrome). |

| People with sessile adenomas that are removed in pieces | 2 to 6 months after adenoma removal | Colonoscopy | If entire adenoma has been removed, further testing should be based on doctor’s judgment. |

Table 3. American Cancer Society Guidelines on Screening and Surveillance for the Early Detection of Colorectal Adenomas and Cancer in People who have had colorectal cancer

| INCREASED RISK – People who have had colorectal cancer | |||

| Risk category | When to test | Recommended test(s) | Comment |

| People diagnosed with colon or rectal cancer | At time of colorectal surgery, or can be 3 to 6 months later if person doesn’t have cancer spread that can’t be removed | Colonoscopy to look at the entire colon and remove all polyps | If the tumor presses on the colon/rectum and prevents colonoscopy, CT colonoscopy (with IV contrast) or double-contrast barium enema (DCBE) may be done to look at the rest of the colon. |

| People who have had colon or rectal cancer removed by surgery | Within 1 year after cancer resection (or 1 year after colonoscopy to make sure the rest of the colon/rectum was clear) | Colonoscopy | If normal, repeat in 3 years. If normal then, repeat test every 5 years. Time between tests may be shorter if polyps are found or there’s reason to suspect Lynch syndrome. After low anterior resection for rectal cancer, exams of the rectum may be done every 3 to 6 months for the first 2 to 3 years to look for signs of recurrence. |

Table 4. American Cancer Society Guidelines on Screening and Surveillance for the Early Detection of Colorectal Adenomas and Cancer in People with a family history of colorectal cancer or adenomatous polyps

| INCREASED RISK – People with a family history | |||

| Risk category | Age to start testing | Recommended test(s) | Comment |

| Colorectal cancer or adenomatous polyps in any first-degree relative before age 60, or in 2 or more first-degree relatives at any age (if not a hereditary syndrome). | Age 40, or 10 years before the youngest case in the immediate family, whichever is earlier | Colonoscopy | Every 5 years. |

| Colorectal cancer or adenomatous polyps in any first-degree relative aged 60 or older, or in at least 2 second-degree relatives at any age | Age 40 | Same test options as for those at average risk. | Same test intervals as for those at average risk. |

Table 5. American Cancer Society Guidelines on Screening and Surveillance for the Early Detection of Colorectal Adenomas and Cancer in People with familial adenomatous polyposis, Lynch syndrome & inflammatory bowel disease

| HIGH RISK | |||

| Risk category | Age to start testing | Recommended test(s) | Comment |

| Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) diagnosed by genetic testing, or suspected FAP without genetic testing | Age 10 to 12 | Yearly flexible sigmoidoscopy to look for signs of FAP; counseling to consider genetic testing if it hasn’t been done | If genetic test is positive, removal of colon (colectomy) should be considered. |

| Lynch syndrome (hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer or HNPCC), or at increased risk of Lynch syndrome based on family history without genetic testing | Age 20 to 25 years, or 10 years before the youngest case in the immediate family | Colonoscopy every 1 to 2 years; counseling to consider genetic testing if it hasn’t been done | Genetic testing should be offered to first-degree relatives of people found to have Lynch syndrome mutations by genetic tests. It should also be offered if 1 of the first 3 of the modified Bethesda criteria is met.* |

| Inflammatory bowel disease: -Chronic ulcerative colitis -Crohn’s disease | Cancer risk begins to be significant 8 years after the onset of pancolitis (involvement of entire large intestine), or 12-15 years after the onset of left-sided colitis | Colonoscopy every 1 to 2 years with biopsies for dysplasia | These people are best referred to a center with experience in the surveillance and management of inflammatory bowel disease. |

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) colon cancer screening guidelines

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) colon cancer screening guidelines is in the process of being updated in 2019.

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) colon cancer screening guidelines – 2021 recommendations 16:

- Adults aged 45 to 75 years: The USPSTF recommends screening for colorectal cancer starting at age 50 years and continuing until age 75 years. The risks and benefits of different screening methods vary.

- Adults aged 76 to 85 years: The USPSTF recommends that clinicians selectively offer screening for colorectal cancer in adults aged 76 to 85 years. Evidence indicates that the net benefit of screening all persons in this age group is small. The decision to screen for colorectal cancer in adults aged 76 to 85 years should be an individual one, taking into account the patient’s overall health, prior screening history and preferences.

- Adults in this age group who have never been screened for colorectal cancer are more likely to benefit.

- Screening would be most appropriate among adults who 1) are healthy enough to undergo treatment if colorectal cancer is detected and 2) do not have comorbid conditions that would significantly limit their life expectancy.

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommended screening strategies include 17:

- High-sensitivity guaiac fecal occult blood test (HSgFOBT) or fecal immunochemical test (FIT) every year

- Stool DNA-FIT every 1 to 3 years

- Computed tomography colonography every 5 years

- Flexible sigmoidoscopy every 5 years

- Flexible sigmoidoscopy every 10 years + annual FIT

- Colonoscopy screening every 10 years

Tests that can find both colorectal polyps and cancer

Flexible sigmoidoscopy

During this test, the doctor looks at part of the colon and rectum with a sigmoidoscope (a flexible, lighted tube about the thickness of a finger with a small video camera on the end). It’s put in through the anus and into the rectum and moved into the lower part of the colon. Images from the scope are seen on a video screen.

Using the sigmoidoscope, your doctor can look at the inside of the rectum and part of the colon to detect (and possibly remove) any abnormality. The sigmoidoscope is only 60 centimeters (about 2 feet) long, so the doctor is able to see the entire rectum but less than half of the colon with this procedure.

This test is not widely used as a screening test for colorectal cancer in the United States.

Before the test: Be sure your doctor knows about any medicines you take. You might need to change how you take them before the test. Your insides must be empty and clean so your doctor can see the lining of the sigmoid colon and rectum. You will get specific instructions to follow to clean them out. You may be asked to follow a special diet (such as drinking only clear liquids) or to use enemas or strong laxatives the day before the test to clean out your colon.

During the test: A sigmoidoscopy usually takes about 10 to 20 minutes. Most people don’t need to be sedated for this test, but this might be an option you can discuss with your doctor. Sedation may make the test less uncomfortable, but you’ll need some time to recover from it and you’ll need someone with you to take you home after the test.

You’ll probably be asked to lie on a table on your left side with your knees pulled up near your chest. Before the test, your doctor may put a gloved, lubricated finger into your rectum to examine it. For the test itself, the sigmoidoscope is first lubricated to make it easier to insert into the rectum. The scope may feel cold as it’s put in. Air will be pumped into the colon through the sigmoidoscope so the doctor can see the walls of the colon better.

If you are not sedated during the procedure, you might feel pressure and slight cramping in your lower belly. To ease discomfort and the urge to have a bowel movement, it helps to breathe deeply and slowly through your mouth. You’ll feel better after the test once the air leaves your colon.

If a polyp is found during the test, the doctor may remove it with a small instrument passed through the scope. The polyp will be looked at in the lab. If a pre-cancerous polyp (an adenoma) or colorectal cancer is found, you’ll need to have a colonoscopy (see below) later to look for polyps or cancer in the rest of the colon.

Possible complications and side effects: This test may be uncomfortable because of the air put into the colon, but it should not be painful. Be sure to let your doctor know if you feel pain during the procedure. You might see a small amount of blood in your first bowel movement after the test. More serious bleeding and puncture of the colon are possible complications, but they are very uncommon.

Figure 5. Sigmoidoscopy. A thin, lighted tube is inserted through the anus and rectum and into the lower part of the colon to look for abnormal areas

Colonoscopy

For this test, the doctor looks at the entire length of the colon and rectum with a colonoscope, a thin, flexible, lighted tube with a small video camera on the end. It’s basically a longer version of a sigmoidoscope. It’s put in through the anus and into the rectum and colon. Special instruments can be passed through the colonoscope to biopsy (sample) or remove any suspicious-looking areas such as polyps, if needed.

Before the test: Be sure your doctor knows about any medicines you are taking. You might need to change how you take them before the test. The colon and rectum must be empty and clean so your doctor can see the lining of the entire colon and rectum during the test. This process of cleaning out the colon and rectum is sometimes unpleasant and can keep people from getting this important screening test done. However, newer kits are available to clean out the bowel and may be better tolerated than previous ones. Your doctor can discuss the options with you.

Your doctor will give you specific instructions. It’s important to read them carefully a few days ahead of time, since you may need to follow a special diet for at least a day before the test and to shop for supplies and laxatives. If you’re not sure about any of the instructions, call the doctor’s office and go over them with the nurse.

You will probably also be told not to eat or drink anything after midnight the night before your test. If you normally take prescription medicines in the mornings, talk with your doctor or nurse about how to manage them for that day.

Because a sedative is used during the test, you will need to arrange for someone you know to take you home after the test. You might need someone to help you get into your home if you are sleepy or dizzy, so many centers that do colonoscopies will not discharge people to go home in a cab or a ridesharing service. If transportation might be a problem, talk with your health care provider about the policy at your hospital or surgery center for using one of these services. There may be other resources available for getting home, depending on the situation.

During the test: The test itself usually takes about 30 minutes, but it may take longer if a polyp is found and removed. Before it starts, you’ll be given a sedating medicine (into a vein) to make you feel relaxed and sleepy during the procedure. For most people, this medicine makes them unaware of what’s going on and unable to remember the procedure afterward. You’ll wake up after the test is over, but might not be fully awake until later in the day.

During the test, you’ll be asked to lie on your side with your knees pulled up. A drape will cover you. Your blood pressure, heart rate, and breathing rate will be monitored during and after the test.

Your doctor might insert a gloved finger into the rectum to examine it before putting in the colonoscope. The colonoscope is lubricated so it can be inserted easily into the rectum. Once in the rectum, the colonoscope is passed all the way to the beginning of the colon, called the cecum.

If you’re awake, you may feel an urge to have a bowel movement when the colonoscope is inserted or pushed further up the colon. The doctor also puts air into the colon through the colonoscope to make it easier to see the lining of the colon and use the instruments to perform the test. To ease any discomfort, it may help to breathe deeply and slowly through your mouth.

The doctor will look at the inner walls of the colon as he or she slowly removes the colonoscope. If a small polyp is found, it may be removed and then sent to a lab to be checked if it has any areas that have changed into cancer. This is because some small polyps may become cancer over time.

If your doctor sees a larger polyp or tumor or anything else abnormal, a biopsy may be done. A small piece of tissue is taken out through the colonoscope. The tissue is checked in the lab to see if it’s cancer, a benign (non-cancerous) growth, or inflammation.

Possible side effects and complications: The bowel preparation before the test is unpleasant. The test itself might be uncomfortable, but the sedative usually helps with this, and most people feel normal once the effects of the sedative wear off. Because air is pumped into the colon during the test, people sometimes feel bloated, have gas pains, or have cramping for a while after the test until the air passes out.

Some people may have low blood pressure or changes in heart rhythm from the sedation during the test, but these are rarely serious.

If a polyp is removed or a biopsy is done during the colonoscopy, you might notice some blood in your stool for a day or 2 after the test. Serious bleeding is uncommon, but in rare cases, bleeding might need to be treated or can even be life-threatening.

Colonoscopy is a safe procedure, but in rare cases the colonoscope can puncture the wall of the colon or rectum. This is called a perforation. Symptoms can include severe abdominal (belly) pain, nausea, and vomiting. This can be a major (or even life-threatening) complication, because it can lead to a serious abdominal (belly) infection. The hole may need to be repaired with surgery. Ask your doctor about the risk of this complication.

Figure 6. Colonoscopy

Double-contrast barium enema (DCBE)

This test is also called an air-contrast barium enema or a barium enema with air contrast. It may also be called a lower GI series. It’s basically a type of x-ray test. Barium sulfate, which is a chalky liquid, and air are put into the colon and rectum through the anus to outline the inner lining. This can show abnormal areas on x-rays. If suspicious areas are seen on this test, a colonoscopy will need to be done to explore them further.

This test is not widely used as a screening test for colorectal cancer in the United States.

Before the test: It’s very important that the colon and rectum are empty and clean so they can be seen during the test. You’ll be given specific instructions on how to prepare for the test. For example, you may be asked to clean your bowel the night before with laxatives and/or take enemas the morning of the exam. You’ll probably be asked to follow a clear liquid diet for at least a day before the test. You may also be told to avoid eating or drinking dairy products the day before the test, and to not eat or drink anything after midnight the night before the test.

During the test: The test takes about 30 to 45 minutes, and sedation isn’t needed. You lie on a table on your side in an x-ray room. A small, flexible tube is put into your rectum, and barium sulfate is pumped in to partially fill and open up the colon and rectum. You are then turned on the x-ray table so the barium moves throughout the colon and rectum. Then air is pumped into the colon and rectum through the same tube to expand them. This might cause some cramping and discomfort, and you may feel the urge to have a bowel movement.

X-ray pictures of the lining of your colon and rectum are then taken to look for polyps or cancers. You may be asked to change positions to help move the barium and so that different views of the colon and rectum can be seen on the x-rays.

If polyps or other suspicious areas are seen on this test, you’ll probably need a colonoscopy to remove them or to study them fully.

Possible side effects and complications: You may have bloating or cramping after the test, and will probably feel the need to empty your bowels soon after the test is done. The barium can cause constipation for a few days, and your stool may look grey or white until all the barium is out. There’s a very small risk that inflating the colon with air could injure or puncture it, but this risk is thought to be much less than with colonoscopy. Like other x-ray tests, this test also exposes you to a small amount of radiation.

Figure 7. Barium enema

CT colonography (virtual colonoscopy)

This test is an advanced type of computed tomography (CT or CAT) scan of the colon and rectum. A CT scan uses x-rays, but instead of taking one picture, like a regular x-ray, a CT scanner takes many pictures as it rotates around you while you lie on a table. A computer then combines these pictures into detailed images of the part of your body being studied.

For CT colonography, special computer programs create both 2-dimensional x-ray pictures and a 3-dimensional view of the inside of the colon and rectum, which lets the doctor look for polyps or cancer.

This test may be especially useful for some people who can’t have or don’t want to have more invasive tests such as colonoscopy. It can be done fairly quickly, and sedation isn’t needed. But even though this test is not invasive like a colonoscopy, the same type of bowel prep is needed. Also, a small, flexible tube is put in the rectum to fill the colon with air. Another possible drawback is that if polyps or other suspicious areas are seen on this test, a colonoscopy will still probably be needed to remove them or to explore them fully.

Before the test: It’s important that the colon and rectum are emptied before this test to get the best images. You’ll probably be told to follow a clear liquid diet for at least a day before the test. There are a number of ways to clean out the colon before the test. Often, the evening before the procedure, you drink large amounts of a liquid laxative solution. This often results in spending a lot of time in the bathroom. The morning of the test, sometimes more laxatives or enemas may be needed to make sure the bowels are empty. Newer kits are available to clean out the bowel and may be better tolerated than previous ones. Your doctor can discuss the options with you.

During the test: This test is done in a special room with a CT scanner. It takes about 10 minutes. You may be asked to drink a contrast solution before the test to help “tag” any stool left in the colon or rectum, which helps the doctor when looking at the test images. You’ll be asked to lie on a narrow table that’s part of the CT scanner, and will have a small, flexible tube put into your rectum. Air is pumped through the tube into the colon and rectum to expand them to provide better images. The table then slides into the CT scanner, and you’ll be asked to hold your breath for about 15 seconds while the scan is done. You’ll likely have 2 scans: one while you’re lying on your back and one while you’re on your stomach or side.

Possible side effects and complications: There are usually few side effects after this test. You may feel bloated or have cramps because of the air in the colon and rectum, but this should go away once the air passes from the body. There’s a very small risk that inflating the colon with air could injure or puncture it, but this risk is thought to be much less than with colonoscopy. Like other types of CT scans, this test also exposes you to a small amount of radiation

Stool-based tests that mainly find colorectal cancer

Stool-based tests look at the stool (feces) for possible signs of colorectal cancer or polyps. These tests are typically done at home, so many people find them easier than tests like a colonoscopy. But these tests need to be done more often. And if the result from one of these stool tests is positive (abnormal), you will still need a colonoscopy to see if you have cancer.

Guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (gFOBT)

One way to test for colorectal cancer is to look for occult (hidden) blood in stool. The idea behind guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (gFOBT) is that blood vessels in larger colorectal polyps or cancers are often fragile and easily damaged by the passage of stool. The damaged vessels usually bleed into the colon, but only rarely is there enough bleeding for blood to be seen in the stool.

The guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (gFOBT) detects blood in the stool through a chemical reaction. This test can’t tell if the blood is from the colon or from other parts of the digestive tract (such as the stomach). If the guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (gFOBT) is positive, a colonoscopy will be needed to find the reason for the bleeding. Although blood in the stool can be from cancers or polyps, it can also have other causes, such as ulcers, hemorrhoids, diverticulosis (tiny pouches that form at weak spots in the colon wall), or inflammatory bowel disease (colitis).

Over time, this test has improved so that it’s now more likely to find colorectal cancer. The American Cancer Society recommends the more modern, highly sensitive versions of this test for screening.

The guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (gFOBT) must be done every year, unlike some other tests (like colonoscopy).

This test is done with a kit that you can use in the privacy of your own home that allows you to check more than one stool sample. A FOBT done during a digital rectal exam in the doctor’s office (which only checks one stool sample) is not enough for proper screening.

People having this test will get a kit with instructions from their doctor’s office or clinic. The kit will explain how to take stool samples at home (usually samples from 3 straight bowel movements are smeared onto small squares of paper). The kit is then returned to the doctor’s office or medical lab (usually within 2 weeks) for testing.

Before the test: Some foods or drugs can affect the results, so you may be instructed to avoid the following before this test:

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen (Advil), naproxen (Aleve), or aspirin, for 7 days before testing. (They can cause bleeding, which can lead to a false-positive result.) Note: People should try to avoid taking NSAIDs for minor aches prior to the test. But if you take these medicines daily for heart problems or other conditions, don’t stop them for this test without talking to your health care provider first.

- Vitamin C more than 250 mg a day from either supplements or citrus fruits and juices for 3 to 7 days before testing. (This can affect the chemicals in the test and make the result negative, even if blood is present.)

- Red meats (beef, lamb, or liver) for 3 days before testing. Components of blood in the meat may cause a positive test result.

Some people who are given the test never do it or don’t return it because they worry that something they ate may affect the test. Even if you are concerned that something you ate may alter the test, the most important thing is to get the test done.

Collecting the samples: Have all of your supplies ready and in one place. Supplies typically include a test kit, test cards, either a brush or wooden applicator, and a mailing envelope. The kit will give you detailed instructions on how to collect the stool samples. Be sure to follow the instructions that come with your kit, as different kits might have different instructions. If you have any questions about how to use your kit, contact your doctor’s office or clinic. Once you have collected the samples, return them as instructed in the kit.

If this test finds blood, you will need a colonoscopy to look for the source. It’s not enough to simply repeat the gFOBT or follow up with other types of tests.

Fecal immunochemical test (FIT)

The fecal immunochemical test (FIT) is also called an immunochemical fecal occult blood test (iFOBT). It tests for occult (hidden) blood in the stool in a different way than the guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (gFOBT). This test reacts to part of the human hemoglobin protein, which is found in red blood cells.

The fecal immunochemical test (FIT) is done much like the guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (gFOBT), in that small amounts of stool are collected on cards (or in tubes). Some people may find this test easier because there are no drug or dietary restrictions (vitamins and foods do not affect the FIT), and collecting the samples may be easier. This test is also less likely to react to bleeding from other parts of digestive tract, such as the stomach.

Like the guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (gFOBT), the fecal immunochemical test (FIT) may not detect a tumor that’s not bleeding, so multiple stool samples should be tested. This test must also be done every year. And if the results are positive for hidden blood, a colonoscopy will be needed to investigate further.

Collecting the samples: Have all of your supplies ready and in one place. Supplies typically include a test kit, test cards or tubes, long brushes or other collecting devices, waste bags, and a mailing envelope. The kit will give you detailed instructions on how to collect the samples. Be sure to follow the instructions that come with your kit, as different kits might have different instructions. If you have any questions about how to use your kit, contact your doctor’s office or clinic. Once you have collected the samples, return them as instructed in the kit.

Stool DNA test

A stool DNA test looks for certain abnormal sections of DNA from cancer or polyp cells. Colorectal cancer cells often have DNA mutations (changes) in certain genes. Cells from colorectal cancers or polyps with these mutations often get into the stool, where tests may be able to detect them. Cologuard® is the only test currently available in the United States, tests for both DNA changes and blood in the stool (FIT).

Collecting the samples: You’ll get a kit in the mail to use to collect your entire stool sample. The kit will have a sample container, a bracket for holding the container in the toilet, a bottle of liquid preservative, a tube, labels, and a shipping box. The kit has detailed instructions on how to collect the sample. Be sure to follow the instructions that come with your kit. If you have any questions about how to use your kit, contact your doctor’s office or clinic. Once you have collected the sample, return it as instructed in the kit.

This test should be done every 3 years. If the test is positive (if it finds DNA changes or blood), a colonoscopy will be needed.

Table 6. The pros and cons of colorectal cancer screening tests

| Test | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Flexible sigmoidoscopy | Fairly quick and safe Usually doesn’t require full bowel prep Sedation usually not used Does not require a specialist Done every 5 years | Looks at only about a third of the colon Can miss small polyps Can’t remove all polyps May be some discomfort Very small risk of bleeding, infection, or bowel tear Colonoscopy will be needed if abnormal |

| Colonoscopy | Can usually look at the entire colon Can biopsy and remove polyps Done every 10 years Can help find some other diseases | Can miss small polyps Full bowel prep needed Costs more on a one-time basis than other forms of testing Sedation is usually needed You will need someone to drive you home You may miss a day of work Small risk of bleeding, bowel tears, or infection |

| Double-contrast barium enema (DCBE) | Can usually see the entire colon Relatively safe Done every 5 years No sedation needed | Can miss small polyps Full bowel prep needed Some false positive test results Can’t remove polyps during testing Colonoscopy will be needed if abnormal |

| CT colonography (virtual colonoscopy) | Fairly quick and safe Can usually see the entire colon Done every 5 years No sedation needed | Can miss small polyps Full bowel prep needed Some false positive test results Can’t remove polyps during testing Colonoscopy will be needed if abnormal Still fairly new – may be insurance issues |

| Guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (gFOBT) | No direct risk to the colon No bowel prep Sampling done at home Inexpensive | Can miss many polyps and some cancers Can produce false-positive test results Pre-test diet changes are needed Needs to be done every year Colonoscopy will be needed if abnormal |