Contents

- Lung cancer

- Types of lung cancer

- Chest anatomy

- Human lungs

- What are Lung Nodules?

- Lung cancer signs and symptoms

- Lung cancer causes

- Lifetime chance of getting lung cancer

- Lung cancer prevention

- Lung cancer screening

- Lung cancer complications

- Lung cancer diagnosis

- Lung cancer staging

- Lung cancer treatment

- Lung cancer prognosis

- Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

- Types of non-small cell lung cancer

- Histopathology of non-small cell lung cancer

- Non-small cell lung cancer causes

- Non-small cell lung cancer prevention

- Non-small cell lung cancer symptoms and signs

- Non-small cell lung cancer diagnosis

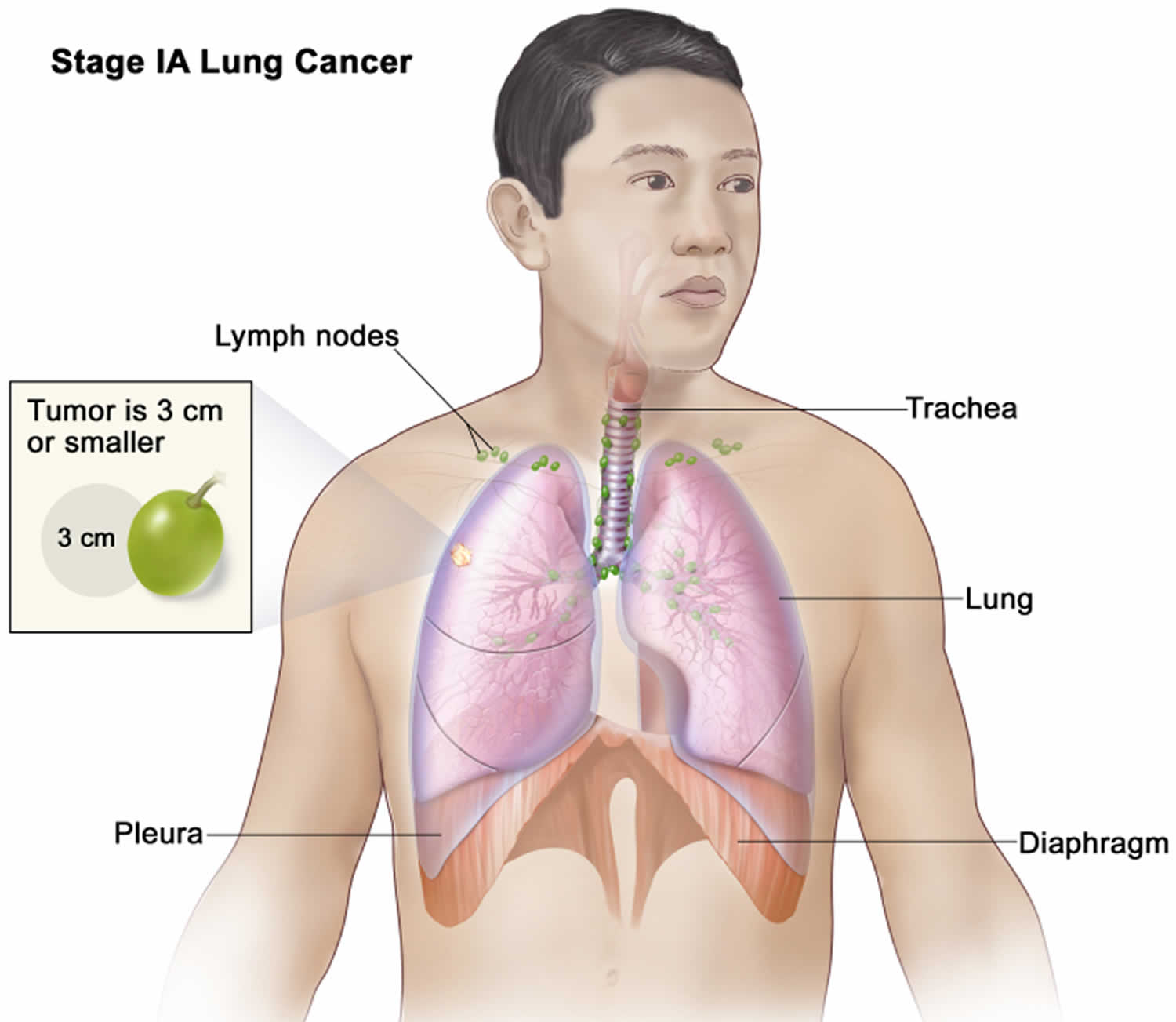

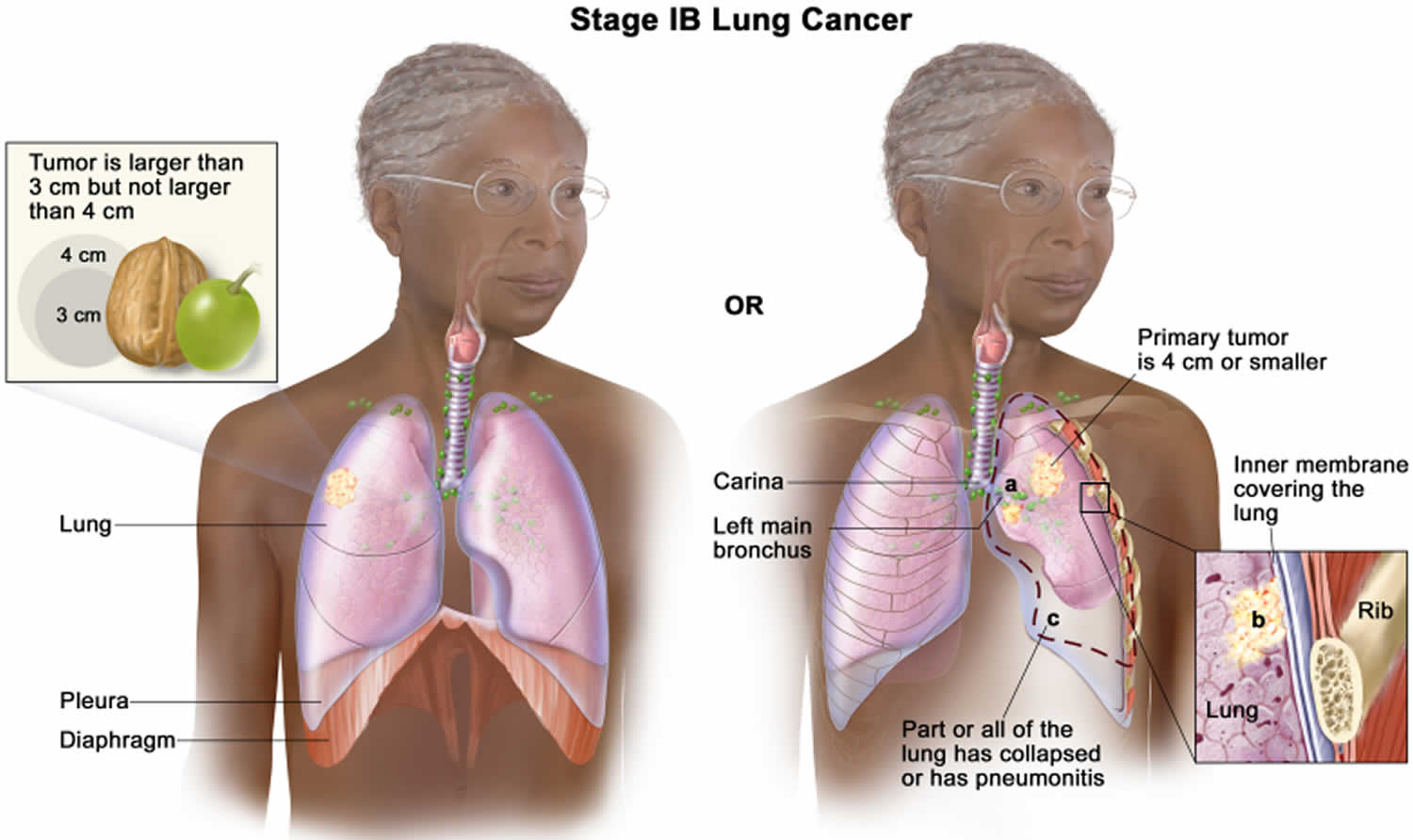

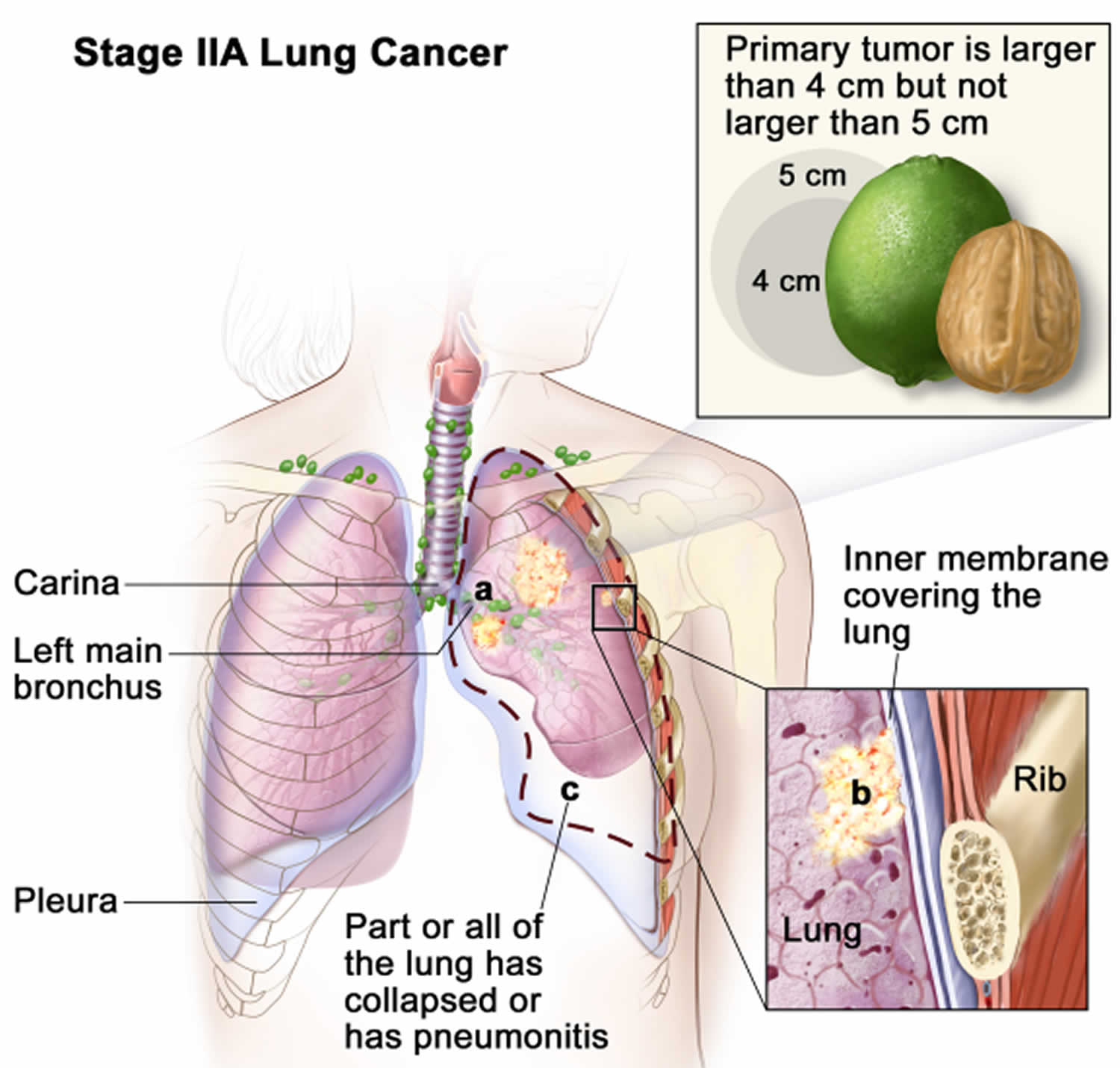

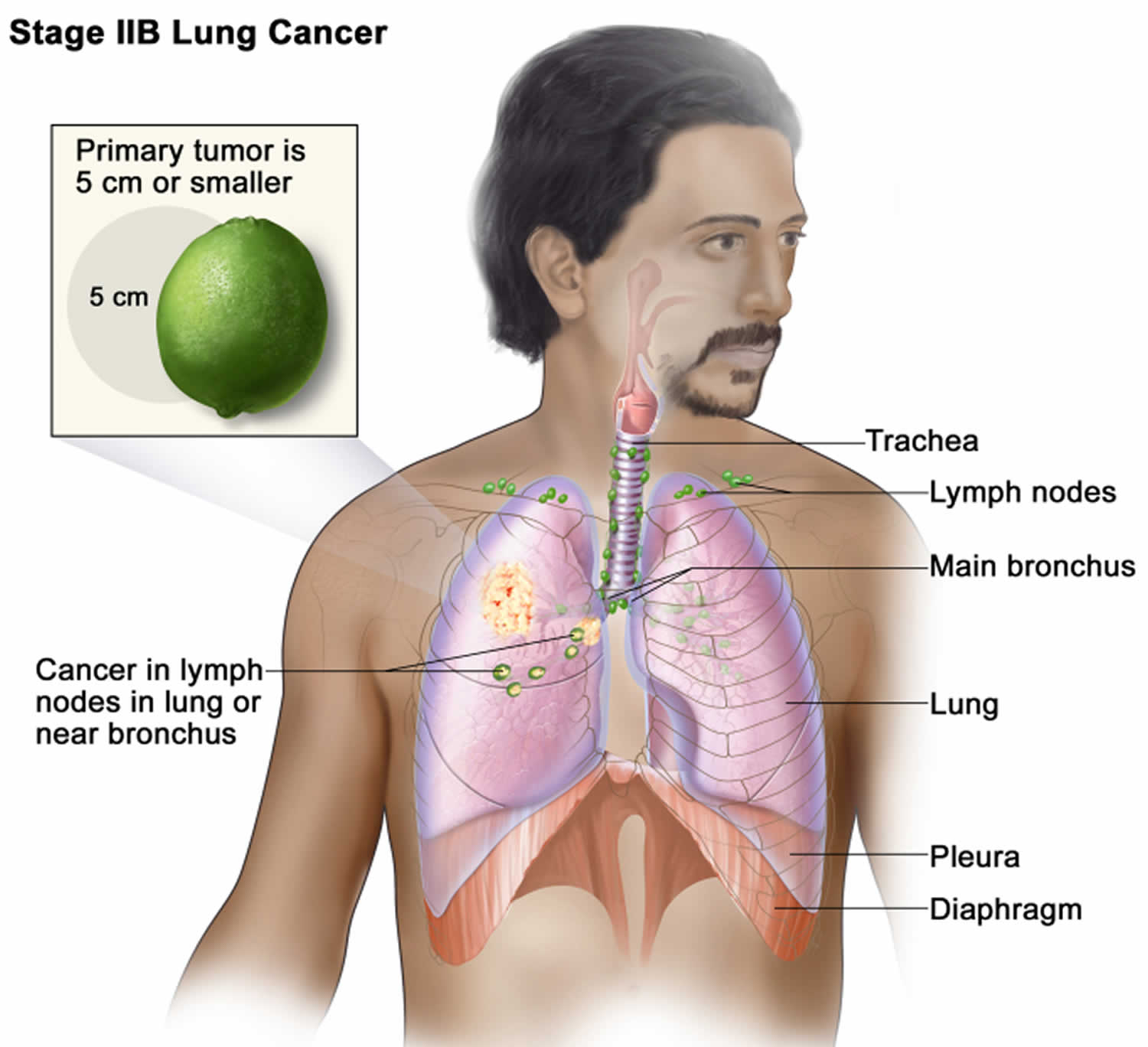

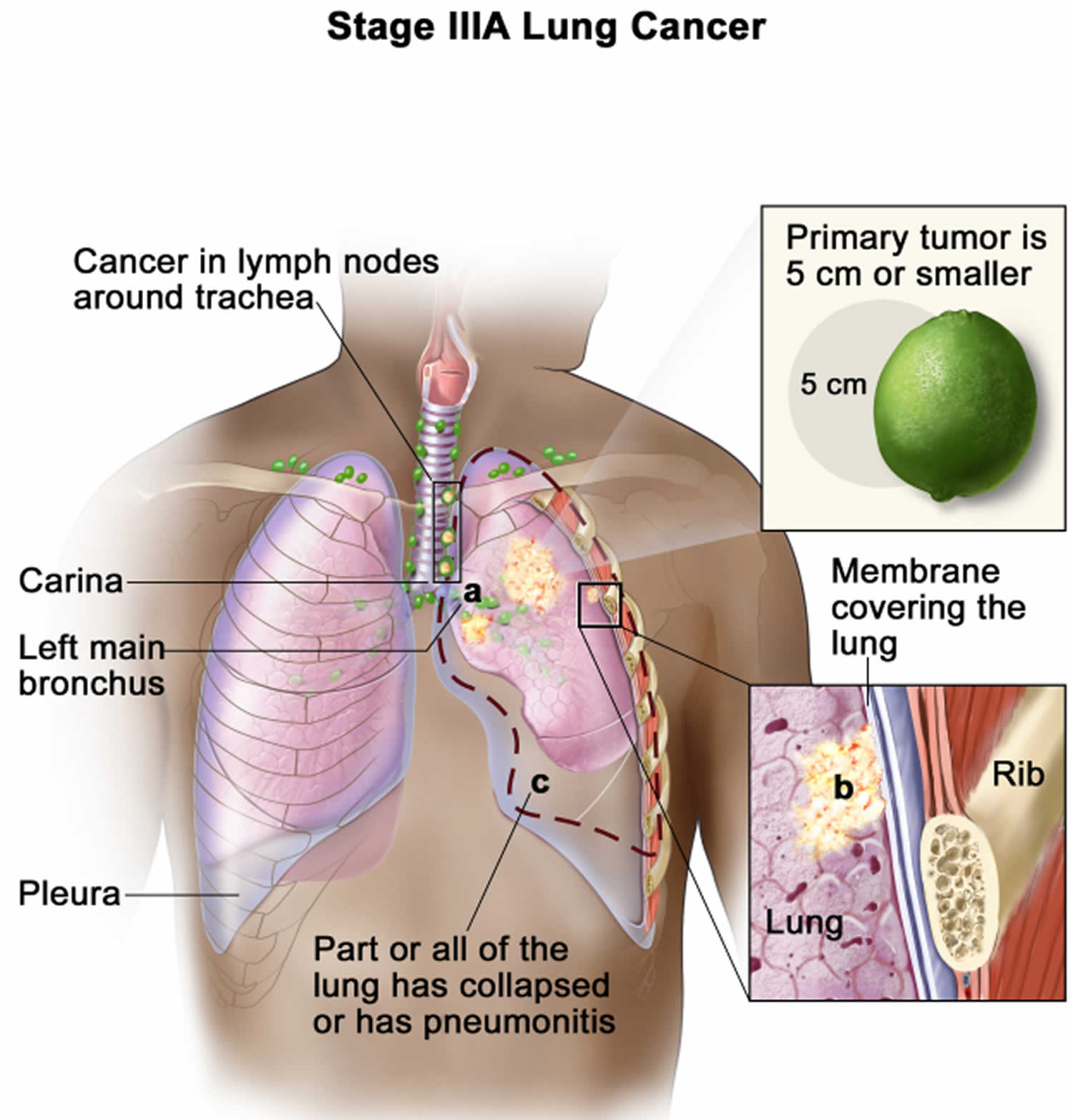

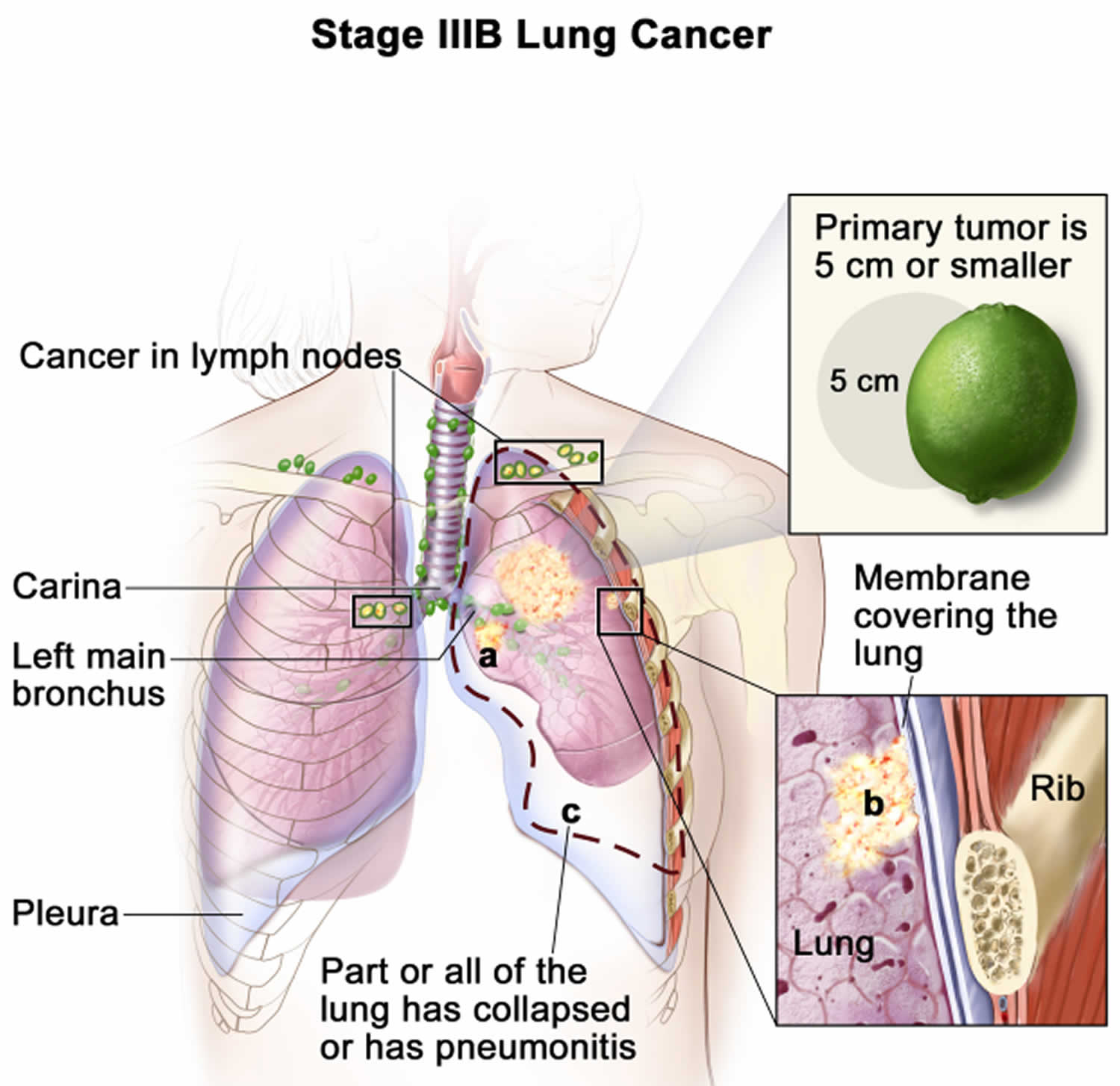

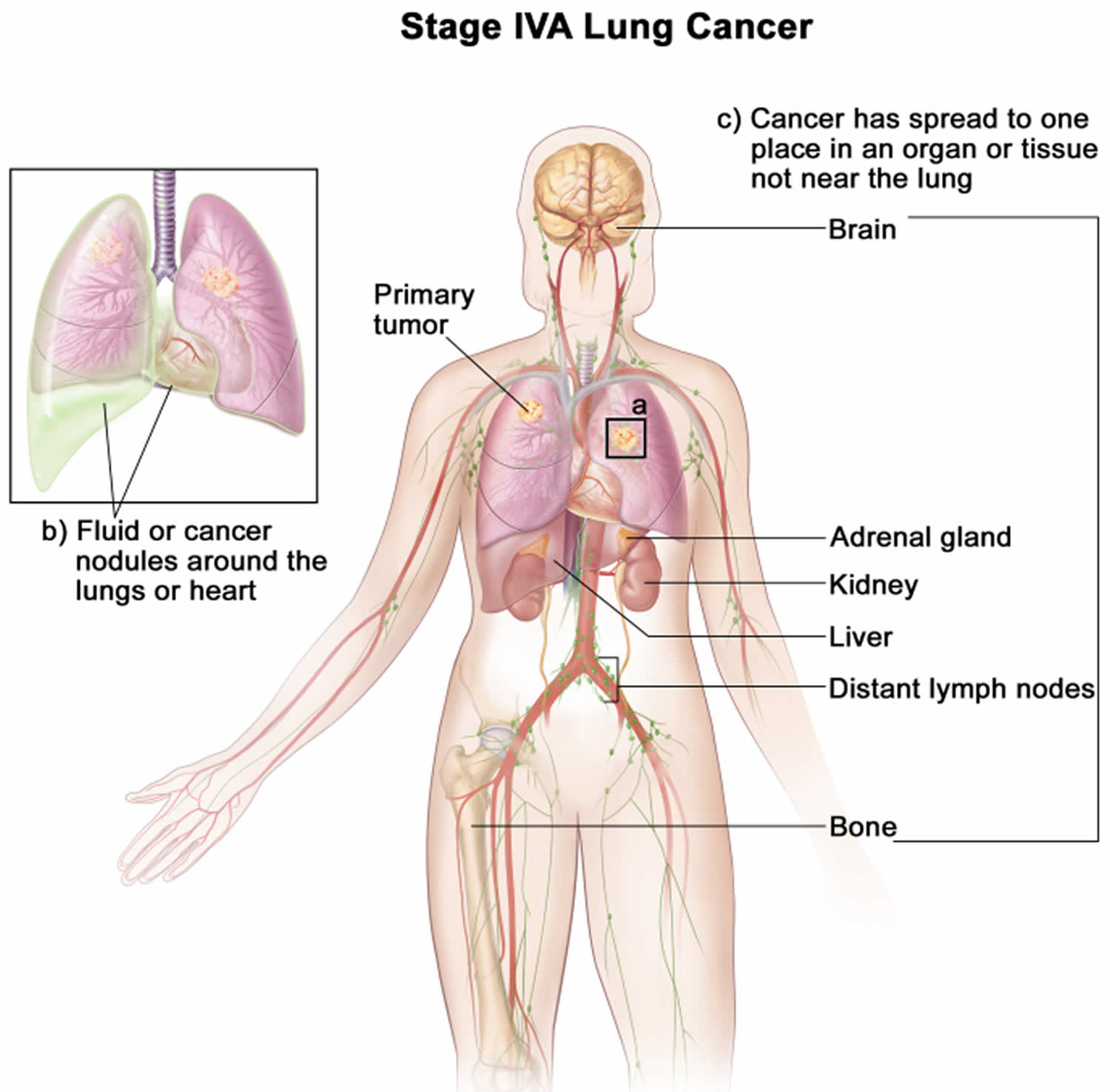

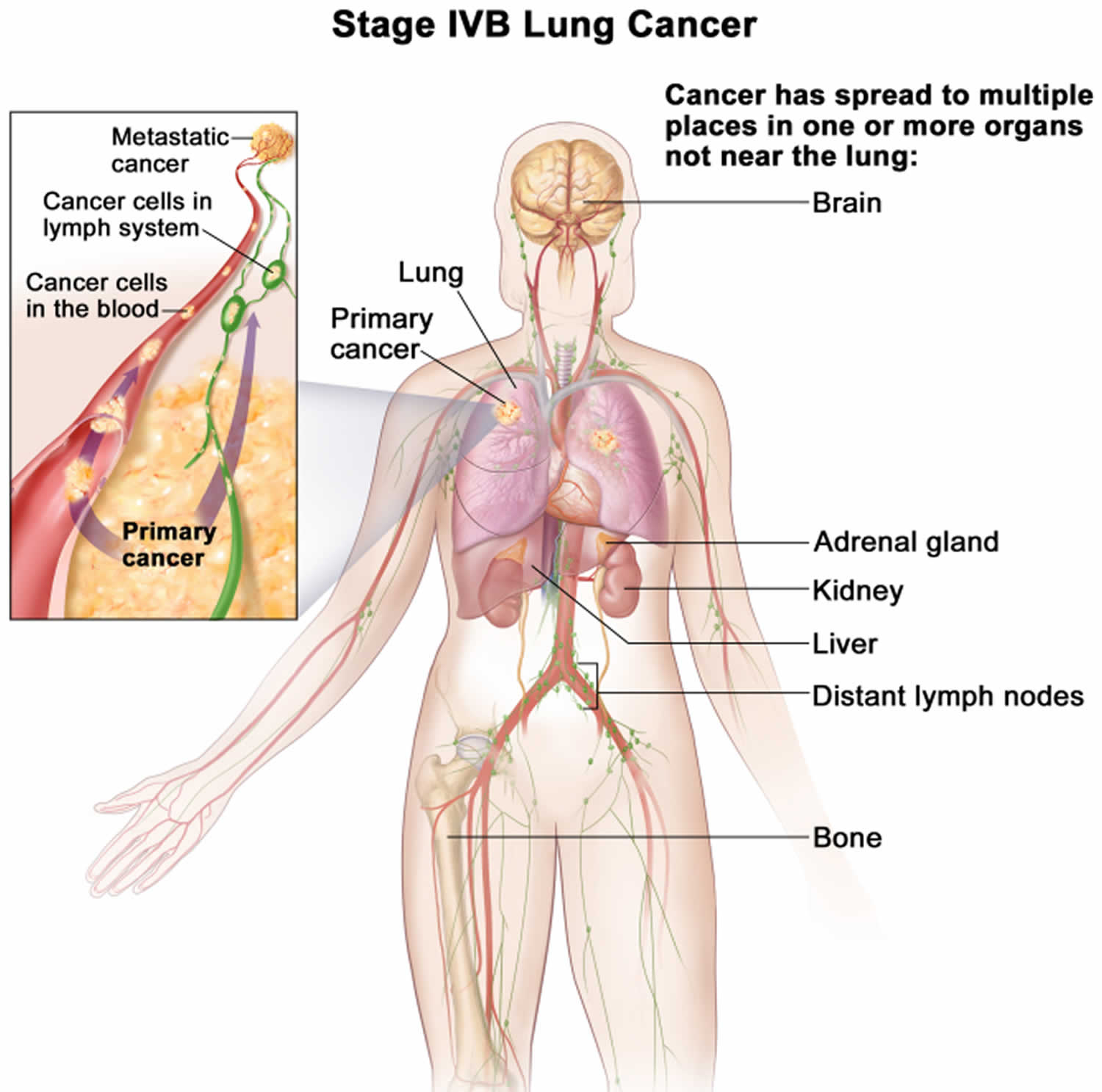

- Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Stages

- Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Survival Rates by Stage

- Non-small cell lung cancer treatment

- Surgery

- Radiation therapy

- Chemotherapy

- Targeted therapy drugs

- Drugs that target tumor blood vessel growth (Angiogenesis inhibitors)

- Drugs that target cells with EGFR changes (EGFR inhibitors)

- Drugs that target cells with ALK gene changes (ALK inhibitors)

- Drugs that target cells with ROS1 gene changes (ROS1 inhibitors)

- Drugs that target cells with BRAF gene changes (BRAF inhibitors)

- Drugs that target cells with RET gene changes (RET inhibitors)

- Drugs that target cells with MET gene changes (MET inhibitors)

- Drugs that target cells with HER2 gene changes (HER2 inhibitors)

- Drugs that target cells with TRK gene changes (TRK inhibitors)

- Radiofrequency Ablation

- Tumor Treating Fields Therapy

- Immunotherapy for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

- Maintenance therapy

- Palliative Procedures for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

- Small cell lung cancer

- Small Cell Lung Cancer causes

- Small Cell Lung Cancer Risk Factors

- Small Cell Lung Cancer prevention

- Small Cell Lung Cancer signs and symptoms

- Small Cell Lung Cancer Diagnosis

- Small Cell Lung Cancer Stages

- Small Cell Lung Cancer Survival Rates by Stage

- Small Cell Lung Cancer Treatment

- Small cell lung cancer prognosis

Lung cancer

Lung cancer is a type of cancer that starts in the windpipe (trachea), the main airway (bronchus) or the lung tissue. Most lung cancer are either small cell lung cancer (SCLC) or non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). In general, about 13% of all lung cancers are small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and about 87% are non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) 1. Lung cancer is one of the most common cancers in the world. Lung cancer is the second most common cancer (not counting skin cancer) and the leading cause of cancer death in the United States 2. In men, prostate cancer is more common, while in women breast cancer is more common 3. About 14% of all new cancers are lung cancers. The most important risk factor and cause for lung cancer is smoking, which results in approximately 85% of all U.S. lung cancer cases 4. The more cigarettes you smoke per day and the earlier you started smoking, the greater your risk of lung cancer. Although the prevalence of smoking has decreased, approximately 37% of U.S. adults are current or former smokers 4. The incidence of lung cancer increases with age and occurs most commonly in persons aged 55 years or older. Increasing age and cumulative exposure to tobacco smoke are the 2 most common risk factors for lung cancer. High levels of pollution, radiation and asbestos exposure may also increase risk.

Lung cancers typically start in the cells lining the bronchi and parts of the lung such as the bronchioles or alveoli. Lung cancer has a poor prognosis, and nearly 90% of persons with lung cancer die of the disease.

There are 2 main types of lung cancer and they are treated very differently:

- Non small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Non-small cell lung cancer is an umbrella term for several types of lung cancers. About 80% to 85% of lung cancers are non small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). The main subtypes of non small cell lung cancer are adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and large cell carcinoma. These subtypes, which start from different types of lung cells are grouped together as non small cell lung cancer because their treatment and prognoses (outlook) are often similar.

- Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) also called oat cell cancer. About 10% to 15% of all lung cancers are small cell lung cancer (SCLC). Small cell lung cancer occurs almost exclusively in heavy smokers. Small cell lung cancer tends to grow and spread faster than non small cell lung cancer. About 70% of people with small cell lung cancer will have cancer that has already spread at the time they are diagnosed. Since this cancer grows quickly, it tends to respond well to chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Unfortunately, for most people, the cancer will return at some point.

- Other types of lung tumors. Along with the main types of lung cancer, other tumors can occur in the lungs.

- Lung carcinoid tumors also known as lung carcinoids: Carcinoid tumors of the lung account for fewer than 5% of lung tumors. Most of these grow slowly. Lung carcinoid tumors start in neuroendocrine cells, a special kind of cell found in the lungs. Neuroendocrine cells are also found in other areas of the body, but only cancers that form from neuroendocrine cells in the lungs are called lung carcinoid tumors.

- There are 2 types of lung carcinoid tumors 5:

- Typical carcinoids tend to grow slowly and rarely spread beyond the lungs. About 9 out of 10 lung carcinoids are typical carcinoids. They also do not seem to be linked with smoking.

- Atypical carcinoids grow a little faster and are somewhat more likely to spread to other organs. They have more cells that are dividing and look more like a fast-growing tumor. They are much less common than typical carcinoids and may be found more often in people who smoke.

- There are 2 types of lung carcinoid tumors 5:

- Other types of lung cancer such as adenoid cystic carcinomas, lymphomas, and sarcomas, as well as benign lung tumors such as hamartomas are rare.

- Cancers that spread to the lungs also known as secondary lung cancer: Cancers that start in other organs (such as the breast, pancreas, kidney, or skin) can sometimes spread (metastasize) to the lungs, but these are not lung cancers. For example, cancer that starts in the breast and spreads to the lungs is still breast cancer, not lung cancer. Treatment for metastatic cancer to the lungs is based on where it started (the primary cancer site).

- Lung carcinoid tumors also known as lung carcinoids: Carcinoid tumors of the lung account for fewer than 5% of lung tumors. Most of these grow slowly. Lung carcinoid tumors start in neuroendocrine cells, a special kind of cell found in the lungs. Neuroendocrine cells are also found in other areas of the body, but only cancers that form from neuroendocrine cells in the lungs are called lung carcinoid tumors.

Cancer that starts in the lung is called primary lung cancer. If cancer spreads to your lungs from somewhere else in your body, this is secondary lung cancer.

Figure 1. Lung cancer types

Footnotes: Overview of non-small cell lung cancer types of cancers that develop from the lung’s epithelial cells, with three main subtypes: adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and large cell carcinoma.

[Source 6 ]People who smoke have the greatest risk of lung cancer 7, though lung cancer can also occur in people who have never smoked. The risk of lung cancer increases with the length of time and number of cigarettes you’ve smoked. Smoking is estimated to account for about 90% of all lung cancer cases 8, with a relative risk of lung cancer approximately 20-fold higher in smokers than in nonsmokers 7. If you quit smoking, even after smoking for many years, you can significantly reduce your chances of developing lung cancer.

Estimated new cases and deaths from lung cancer (non–small cell lung cancer and small cell lung cancer combined) in the United States in 2025 8, 8, 1:

- New cases: About 226,650 new cases of lung cancer (110,680 in men and 115,970 in women). The number of new lung cancer cases continues to decrease, partly because people are quitting smoking 9. However, in developing countries, non-small cell lung cancer cases are rising due to higher smoking rates and growing industrialization 6.

- Deaths: About 124,730 deaths from lung cancer (64,190 in men and 60,540 in women). Death rates for lung cancer are higher among the middle-aged and older populations. Lung and bronchus cancer is the first leading cause of cancer death in the United States. The death rate was 32.4 per 100,000 men and women per year based on 2018–2022 deaths, age-adjusted.

- 5-Year Relative Survival: 26.7%. Relative survival is an estimate of the percentage of patients who would be expected to survive the effects of their cancer. It excludes the risk of dying from other causes. Because survival statistics are based on large groups of people, they cannot be used to predict exactly what will happen to an individual patient. No two patients are entirely alike, and treatment and responses to treatment can vary greatly.

- Percentage of All Cancer Deaths: 20.4%. Lung cancer is by far the leading cause of cancer death, making up almost 20.4% of all cancer deaths. Each year, more people die of lung cancer than of colon, breast, and prostate cancers combined.

- The percent of lung and bronchus cancer deaths is highest among people aged 65–74. With the Median Age At Death 72 years of age.

- Rate of New Lung Cancer Cases and Deaths per 100,000: The rate of new cases of lung and bronchus cancer was 49 per 100,000 men and women per year. The death rate was 32.4 per 100,000 men and women per year. These rates are age-adjusted and based on 2017–2021 cases and 2018–2022 deaths.

- Lifetime Risk of Developing Lung Cancer: Approximately 5.7 percent of men and women will be diagnosed with lung and bronchus cancer at some point during their lifetime, based on 2018–2021 data.

- Prevalence of Lung Cancer: In 2021, there were an estimated 610,816 people living with lung and bronchus cancer in the United States.

Lung cancer mainly occurs in older people. About 2 out of 3 people diagnosed with lung cancer are 65 or older, while less than 2% are younger than 45. The average age at the time of diagnosis is about 70 3.

The 5-year relative survival rate from 2014 to 2020 for patients with lung cancer was 26.7% 8. The 5-year relative survival rate for patients with local-stage (63.7%), regional-stage (35.9%), and distant-stage (8.9%) disease varies markedly, depending on the stage at diagnosis 8. However, early-stage non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has a better prognosis and can be treated with surgical resection.

The type of lung cancer you have tells you the type of cell that the cancer started in. Knowing this helps your doctor decide which treatment you need.

Lung cancer typically doesn’t cause signs and symptoms in its earliest stages. Signs and symptoms of lung cancer typically occur when the disease is advanced. Common symptoms of lung cancer may include 10:

- A cough that doesn’t go away and gets worse over time

- Constant chest pain

- Coughing up blood, even a small amount

- Shortness of breath or wheezing

- Hoarseness of voice

- Repeated problems with pneumonia or bronchitis

- Frequent chest infections

- Swelling of the neck and face

- Difficulty swallowing

- Loss of appetite

- Weight loss without trying

- Fatigue

- Bone pain

- Headache

- Some people have swollen fingers and nails called finger clubbing. They may also have pain and swelling in their joints. This condition is called hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy (HPOA).

You should see your doctor right away if you have new symptoms that concern you, especially those listed above. This is particularly important if you have risk factors for lung cancer such as a history of lung disease, a family history of lung cancer or you are a smoker.

Doctors diagnose lung cancer using a physical exam, imaging, and lab tests. Treatment depends on the type, stage, and how advanced it is. Treatments include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and targeted therapy. Targeted therapy uses substances that attack cancer cells without harming normal cells. Together, you and your medical team can create a cancer treatment plan that contains the goals of your cancer treatment and the steps that these involve.

Treatment for lung cancer usually begins with surgery to remove the cancer. If your lung cancer is very large or has spread to other parts of your body, surgery may not be possible. Treatment might start with medicine and radiation instead. Your medical team considers many factors when creating a treatment plan. These factors may include your overall health, the type and stage of your cancer, and your preferences.

Some people with lung cancer choose not to have treatment. For instance, you may feel that the side effects of treatment will outweigh the potential benefits. When that’s the case, your doctor may suggest comfort care to treat only the symptoms the cancer is causing.

The prognosis of lung cancer depends on how advanced it was at diagnosis (staging), the effectiveness of cancer treatment and your general health. Your doctor can discuss realistic expectations for your own prognosis.

Types of lung cancer

There are 2 main types of lung cancer 11. Knowing which type you have is important because it affects your treatment options and your outlook (prognosis). If you aren’t sure which type of lung cancer you have, ask your doctor so you can get the right information.

- Non small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). About 80% to 85% of lung cancers are non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Non-small cell lung cancer is an umbrella term for several types of lung cancers. The main subtypes of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) are adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and large cell carcinoma. These subtypes, which start from different types of lung cells are grouped together as non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) because their treatment and prognoses (outlook) are often similar.

- Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) also known as oat cell cancer. About 10% to 15% are small cell lung cancer (SCLC). Small cell lung cancers are also classed as neuroendocrine tumors. Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are rare tumors that develop in cells of the neuroendocrine system. In small cell lung cancer, the tumor starts in the neuroendocrine cells of the lung. Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) tends to grow and spread faster than non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). About 70% of people with small cell lung cancer (SCLC) will have cancer that has already spread at the time they are diagnosed. Since this cancer grows quickly, it tends to respond well to chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Unfortunately, for most people, the cancer will return at some point.

Along with the 2 main types of lung cancer (non-small cell lung cancer and small cell lung cancer), other tumors can occur in the lungs.

- Lung carcinoid tumors also known as lung carcinoids: Carcinoid tumors of the lung account for fewer than 5% of lung tumors. Most of these grow slowly. Lung carcinoid tumors start in neuroendocrine cells, a special kind of cell found in the lungs. Neuroendocrine cells are also found in other areas of the body, but only cancers that form from neuroendocrine cells in the lungs are called lung carcinoid tumors.

- There are 2 types of lung carcinoid tumors 5:

- Typical carcinoids tend to grow slowly and rarely spread beyond the lungs. About 9 out of 10 lung carcinoids are typical carcinoids. They also do not seem to be linked with smoking.

- Atypical carcinoids grow a little faster and are somewhat more likely to spread to other organs. They have more cells that are dividing and look more like a fast-growing tumor. They are much less common than typical carcinoids and may be found more often in people who smoke.

- There are 2 types of lung carcinoid tumors 5:

- Other types of lung cancer such as adenoid cystic carcinomas, lymphomas, and sarcomas, as well as benign lung tumors such as hamartomas are rare. These are treated differently from the more common lung cancers.

- Cancers that spread to the lungs: Cancers that start in other organs (such as the breast, pancreas, kidney, or skin) can sometimes spread (metastasize) to the lungs, but these are not lung cancers. For example, cancer that starts in the breast and spreads to the lungs is still breast cancer, not lung cancer. Treatment for metastatic cancer to the lungs is based on where it started (the primary cancer site).

Chest anatomy

Your chest cavity also called the thoracic cavity is formed by the ribs, the muscles of the chest, the sternum (breastbone), and the thoracic portion of the vertebral column. Within your thoracic cavity are 3 smaller cavities: (a) 2 pleural cavities (fluid-filled spaces one around each lung), your left pleural cavity (holds your left lung) and your right pleural cavity (holds your right lung) and (b) a central portion of your thoracic cavity between your lungs called the mediastinum (media- = middle; -stinum = partition). The mediastinum is the central portion of your thoracic cavity between your lungs, extending from the base of your neck (from your first rib and sternum) to the diaphragm. The mediastinum contains your heart (pericardial cavity, peri- = around; -cardial = heart, a fluid-filled space that surrounds your heart), the major blood vessels connected to your heart and lungs, the trachea (windpipe) and bronchi, the esophagus (foodpipe), the thymus, and lymph nodes but not your lungs. Your right and left lungs are on either side of the mediastinum. The diaphragm is a dome-shaped muscle that separates the thoracic cavity from the abdominopelvic cavity.

Your mediastinum is divided into several parts, which researchers call compartments. The traditional or classical model divides your mediastinum into four parts:

- Superior mediastinum: The top part, located superior to (above) your heart.

- Anterior mediastinum: The part anterior to (in front of) your heart, between your heart and your sternum (breastbone).

- Middle mediastinum: The part that contains your heart.

- Posterior mediastinum: The part posterior to (behind) your heart.

A membrane is a thin, pliable tissue that covers, lines, partitions, or connects internal organs (viscera). One example is a slippery, double-layered membrane associated with body cavities that does not open directly to the exterior called a serous membrane. Serous membrane covers your internal organs (viscera) within the thoracic and abdominal cavities and also lines the walls of the thorax and abdomen. The parts of a serous membrane are (1) the parietal layer (outer layer), a thin epithelium that lines the walls of the cavities, and (2) the visceral layer (inner layer), a thin epithelium that covers and adheres to the viscera within the cavities. Between the two layers is a potential space that contains a small amount of lubricating fluid (serous fluid). The fluid allows the internal organs (viscera) to slide somewhat during movements, such as when the lungs inflate and deflate during breathing.

Within the right and left sides of your thoracic cavity (chest cavity), the compartments that contain your lungs, on either side of the mediastinum, are lined with a membrane called the parietal pleura (outer serous membrane) lining the inside of your rib cage (parietal pleura lines the chest wall) and covering the superior surface of the diaphragm. A similar membrane, called the visceral pleura (inner serous membrane), clings to the surface of your lungs forming the external surface of your lung. The visceral (inner) and parietal (outer) pleural membranes are separated only by a thin film of watery fluid called serous fluid, which is secreted by the parietal and visceral pleural membranes. Although no actual space normally exists between the parietal (outer) and visceral (inner) pleural membranes, the potential space between them is called the pleural cavity. The parietal pleura (outer membrane) and visceral pleura (inner membrane) slide with little friction across the cavity walls as your lungs move, expand and collapse during respiration.

Figure 1. Chest cavity

Footnote: The black dashed lines indicate the borders of the mediastinum.

Figure 2. Mediastinum

Human lungs

The lungs are soft, spongy, cone-shaped organs in the thoracic (chest) cavity. The lungs consist largely of air tubes and spaces. The balance of the lung tissue, its stroma, is a framework of connective tissue containing many elastic fibers. As a result, the lungs are light, soft, spongy, elastic organs that each weigh only about 0.6 kg (1.25 pounds). The elasticity of healthy lungs helps to reduce the effort of breathing.

The left and right lungs are situated in the left and right pleural cavities inside the thoracic cavity. They are separated from each other by the heart and other structures of the mediastinum, which divides the thoracic cavity into two anatomically distinct chambers. As a result, if trauma causes one lung to collapse, the other may remain expanded. Below the lungs, a thin, dome-shaped muscle called the diaphragm separates the chest from the abdomen. When you breathe, the diaphragm moves up and down, forcing air in and out of the lungs. The thoracic cage encloses the rest of the lungs.

Each lung occupies most of the space on its side of the thoracic cavity. A bronchus and some large blood vessels suspend each lung in the cavity. These tubular structures enter the lung on its medial surface.

Parietal refers to a membrane attached to the wall of a cavity; visceral refers to a membrane that is deeper—toward the interior—and covers an internal organ, such as a lung. Within the thoracic (chest) cavity, the compartments that contain the lungs, on either side of the mediastinum, are lined with a membrane called the parietal pleura. A similar membrane, called the visceral pleura, covers each lung.

The parietal and visceral pleural membranes are separated only by a thin film of watery fluid (serous fluid), which they secrete. Although no actual space normally exists between these membranes, the potential space between them is called the pleural cavity.

A thin lining layer called the pleura surrounds the lungs. The pleura protects your lungs and helps them slide back and forth against the chest wall as they expand and contract during breathing. A layer of serous membrane, the visceral pleura, firmly attaches to each lung surface and folds back to become the parietal pleura. The parietal pleura, in turn, borders part of the mediastinum and lines the inner wall of the thoracic cavity and the superior surface of the diaphragm.

In certain conditions, the pleural cavities may fill with air (pneumothorax), blood (hemothorax), or pus. Air in the pleural cavities, most commonly introduced in a surgical opening of the chest or as a result of a stab or gunshot wound, may cause the lungs to collapse. This collapse of a part of a lung, or rarely an entire lung, is called atelectasis. The goal of treatment is the evacuation of air (or blood) from the pleural space, which allows the lung to reinflate. A small pneumothorax may resolve on its own, but it is oft en necessary to insert a chest tube to assist in evacuation.

The thoracic (chest) cavity is divided by a thick wall called the mediastinum. This is the region between the lungs, extending from the base of the neck to the diaphragm. It is occupied by the heart, the major blood vessels connected to it, the esophagus, the trachea and bronchi, and a gland called the thymus.

Each lung is a blunt cone with the tip, or apex, pointing superiorly. The apex on each side extends into the base of the neck, superior to the first rib. The broad concave inferior portion, or base, of each lung rests on the superior surface of the diaphragm.

On the medial (mediastinal) surface of each lung is an indentation, the hilum, through which blood vessels, bronchi, lymphatic vessels, and nerves enter and exit the lung. Collectively, these structures attach the lung to the mediastinum and are called the root of the lung. The largest components of this root are the pulmonary artery and veins and the main (primary) bronchus. Because the heart is tilted slightly to the left of the median plane of the thorax, the left and right lungs differ slightly in shape and size.

Within each root and located in the hilum are:

- a pulmonary artery,

- two pulmonary veins,

- a main bronchus,

- bronchial vessels,

- nerves, and

- lymphatics.

Generally, the pulmonary artery is superior at the hilum, the pulmonary veins are inferior, and the bronchi are somewhat posterior in position. On the right side, the lobar bronchus to the superior lobe branches from the main bronchus in the root, unlike on the left where it branches within the lung itself, and is superior to the pulmonary artery.

Figure 3. Lungs anatomy

Figure 4. Hilum (roots) of the lungs

Several deep fissures divide the two lungs into different patterns of lobes.

- The left lung is divided into two lobes, the superior lobe and the inferior lobe, by the oblique fissure. The left lung is somewhat smaller than the right and has a cardiac notch, a deviation in its anterior border that accommodates the heart.

- The right lung is partitioned into three lobes, the superior, middle, and inferior lobes, by the oblique and horizontal fissures.

Each lung lobe is served by a lobar (secondary) bronchus and its branches. Each of the lobes, in turn, contains a number of bronchopulmonary segments separated from one another by thin partitions of dense connective tissue. Each segment receives air from an individual segmental (tertiary) bronchus. There are approximately ten bronchopulmonary segments arranged in similar, but not identical, patterns in each of the two lungs.

The bronchopulmonary segments have clinical significance in that they limit the spread of some diseases within the lung, because infections do not easily cross the connective tissue partitions between them. Furthermore, because only small veins span these partitions, surgeons can neatly remove segments without cutting any major blood vessels.

The smallest subdivision of the lung that can be seen with the naked eye is the lobule. Appearing on the lung surface as hexagons ranging from the size of a pencil eraser to the size of a penny, each lobule is served by a bronchiole and its branches. In most city dwellers and in smokers, the connective tissue that separates the individual lobules is blackened with carbon.

Each lung has a half-cone shape, with a base, apex, two surfaces, and three borders.

- The base sits on the diaphragm.

- The apex projects above rib I and into the root of the neck.

- The two surfaces-the costal surface lies immediately adjacent to the ribs and intercostal spaces of the thoracic wall. The mediastinal surface lies against the mediastinum anteriorly and the vertebral column posteriorly and contains the comma-shaped hilum of the lung, through which structures enter and leave.

- The three borders-the inferior border of the lung is sharp and separates the base from the costal surface. The anterior and posterior borders separate the costal surface from the medial surface. Unlike the anterior and inferior borders, which are sharp, the posterior border is smooth and rounded.

Right lung

The right lung has three lobes and two fissures. Normally, the lobes are freely movable against each other because they are separated, almost to the hilum, by invaginations of visceral pleura. These invaginations form the fissures:

- The oblique fissure separates the inferior lobe (lower lobe) from the superior lobe and the middle lobe of the right lung.

- The horizontal fissure separates the superior lobe (upper lobe) from the middle lobe.

The approximate position of the oblique fissure on a patient, in quiet respiration, can be marked by a curved line on the thoracic wall that begins roughly at the spinous process of the vertebra TIV level of the spine, crosses the fifth interspace laterally, and then follows the contour of rib VI anteriorly.

The horizontal fissure follows the fourth intercostal space from the sternum until it meets the oblique fissure as it crosses rib V.

The orientations of the oblique and horizontal fissures determine where clinicians should listen for lung sounds from each lobe. The largest surface of the superior lobe is in contact with the upper part of the anterolateral wall and the apex of this lobe proj ects into the root of the neck. The surface of the middle lobe lies mainly adjacent to the lower anterior and lateral wall. The costal surface of the inferior lobe is in contact with the posterior and inferior walls.

The medial surface of the right lung lies adjacent to a number of important structures in the mediastinum and the root of the neck. These include the:

- heart,

- inferior vena cava,

- superior vena cava,

- azygos vein, and

- esophagus.

The right subclavian artery and vein arch over and are related to the superior lobe of the right lung as they pass over the dome of the cervical pleura and into the axilla.

Left lung

The left Iung is smaller than the right lung and has two lobes separated by an oblique fissure. The oblique fissure of the left lung is slightly more oblique than the corresponding fissure of the right lung. During quiet respiration, the approximate position of the left oblique fissure can be marked by a curved line on the thoracic wall that begins between the spinous processes of thoracic vertebrae 3 (T3) and thoracic vertebrae 4 (TIV), crosses the fifth interspace laterally, and follows the contour of 6th rib anteriorly.

As with the right lung, the orientation of the oblique fissure determines where to listen for lung sounds from each lobe. The largest surface of the superior lobe is in contact with the upper part of the anterolateral wall, and the apex of this lobe proj ects into the root of the neck. The costal surface of the inferior lobe is in contact with the posterior and inferior walls.

The inferior portion o f the medial surface of the left lung, unlike the right lung, is notched because of the heart’s projection into the left pleural cavity from the middle mediastinum. From the anterior border of the lower part of the superior lobe a tongue-like extension (the lingula of the left lung) projects over the heart bulge.

The medial surface of the left lung lies adjacent to a number of important structures in the mediastinum and root of the neck. These include the:

- heart,

- aortic arch,

- thoracic aorta, and

- esophagus.

The left subclavian artery and vein arch over and are related to the superior lobe of the left lung as they pass over the dome of the cervical pleura and into the axilla.

Bronchial tree

The trachea is a flexible tube that extends from cervical spine C6 (vertebral level C VI) in the lower neck to thoracic spine T4-T5 (vertebral level T4 to T5) in the mediastinum where it bifurcates into a right and a left main bronchus. The trachea is held open by C-shaped transverse cartilage rings embedded in its wall the open part of the C facing posteriorly. The lowest tracheal ring has a hook-shaped structure, the carina, that projects backwards in the midline between the origins of the two main bronchi. The posterior wall of the trachea is composed mainly of smooth muscle. Each main bronchus enters the root of a lung and passes through the hilum into the lung itself. The right main bronchus is wider and takes a more vertical course through the root and hilum than the left main bronchus. Therefore, inhaled foreign bodies tend to lodge more frequently on the right side than on the left.

The bronchial tree consists of branched airways leading from the trachea to the microscopic air sacs in the lungs. Its branches begin with the right and left main (primary) bronchi, which arise from the trachea at the level of the fifth thoracic vertebra. Each bronchus enters its respective lung. A short distance from its origin, each main bronchus divides into lobar (secondary) bronchi. The lobar bronchi branch into segmental (tertiary) bronchi, which supply bronchopulmonary segments. Within each bronchopulmonary segment, the segmental bronchi give rise to multiple generations of divisions of increasingly finer tubes and, ultimately, to bronchioles , which further subdivide to terminal bronchioles, respiratory bronchioles, and finally to very thin tubes called alveolar ducts. These ducts lead to thin-walled outpouchings called alveolar sacs. Alveolar sacs lead to smaller, microscopic air sacs called alveoli (singular, alveolus), which lie within capillary networks (Figure 6). The alveoli are the sites of gas exchange between the inhaled air and the bloodstream.

The structure of a bronchus is similar to that of the trachea, but the tubes that branch from it have less cartilage in their walls, and the bronchioles lack cartilage. As the cartilage diminishes, a layer of smooth muscle surrounding the tube becomes more prominent. This muscular layer persists even in the smallest bronchioles, but only a few muscle cells are associated with the alveolar ducts.

The absence of cartilage in the bronchioles allows their diameters to change in response to contraction of the smooth muscle in their walls, similar to what happens with arterioles of the cardiovascular system. Part of the “fight-or-flight” response, triggered by the sympathetic nervous system, is bronchodilation, in which the smooth muscle relaxes and the airways become wider and allow more airflow. The opposite, bronchoconstriction, occurs when the smooth muscle contracts and it becomes difficult to move air in and out of the lungs. Bronchoconstriction can occur with allergies. Asthma is an extreme example of bronchoconstriction.

The mucous membranes of the bronchial tree continue to filter the incoming air, and the many branches of the tree distribute the air to alveoli throughout the lungs. The alveoli, in turn, provide a large surface area of thin simple squamous epithelial cells through which gases are easily exchanged. Oxygen diffuses from the alveoli into the blood in nearby capillaries, and carbon dioxide diffuses from the blood into the alveoli.

Figure 5. Bronchial tree of the lungs

Bronchopulmonary segments

A bronchopulmonary segment is the area of lung supplied by a segmental bronchus and its accompanying pulmonary artery branch. Tributaries of the pulmonary vein tend to pass intersegmentally between and around the margins of segments. Each bronchopulmonary segment is shaped like an irregular cone, with the apex at the origin of the segmental bronchus and the base projected peripherally onto the surface of the lung.

A bronchopulmonary segment is the smallest functionally independent region of a lung and the smallest area of lung that can be isolated and removed without affecting adjacent regions.

There are ten bronchopulmonary segments in each lung; some of them fuse in the left lung.

Figure 6. Bronchopulmonary segments

Lung Alveoli

Each human lung is a spongy mass composed of 150 million little sacs, the alveoli. These provide about 70 m², per lung, of gas-exchange surface—about equal to the floor area of a handball court or a room about 8.4 m (25 ft) square.

An alveolus is a pouch about 0.2 to 0.5 mm in diameter. Thin, broad cells called squamous (type I) alveolar cells cover about 95% of the alveolar surface area. Their thinness allows for rapid gas diffusion between the air and blood. The other 5% is covered by round to cuboidal great (type II) alveolar cells. Even though they cover less surface area, these considerably outnumber the squamous alveolar cells.

Great (type II) alveolar cells have two functions:

- They repair the alveolar epithelium when the squamous cells are damaged; and

- They secrete pulmonary surfactant, a mixture of phospholipids and protein that coats the alveoli and smallest bronchioles and prevents the bronchioles from collapsing when one exhales.

The most numerous of all cells in the lung are alveolar macrophages (dust cells), which wander the lumens of the alveoli and the connective tissue between them. These cells keep the alveoli free of debris by phagocytizing dust particles that escape entrapment by mucus in the higher parts of the respiratory tract. In lungs that are infected or bleeding, the macrophages also phagocytize bacteria and loose blood cells. As many as 100 million alveolar macrophages perish each day as they ride up the mucociliary escalator to be swallowed and digested, thus ridding the lungs of their load of debris.

Each alveolus is surrounded by a web of blood capillaries supplied by small branches of the pulmonary artery. The barrier between the alveolar air and blood, called the respiratory membrane, consists only of the squamous alveolar cell, the squamous endothelial cell of the capillary, and their shared basement membrane. These have a total thickness of only 0.5 μm, just 1/15 the diameter of a single red blood cell.

It is very important to prevent fluid from accumulating in the alveoli, because gases diffuse too slowly through liquid to sufficiently aerate the blood. Except for a thin film of moisture on the alveolar wall, the alveoli are kept dry by the absorption of excess liquid by the blood capillaries. The mean blood pressure in these capillaries is only 10 mm Hg compared to 30 mm Hg at the arterial end of the average capillary elsewhere. This low blood pressure is greatly overridden by the oncotic pressure that retains fluid in the capillaries, so the osmotic uptake of water overrides filtration and keeps the alveoli free of fluid. The lungs also have a more extensive lymphatic drainage than any other organ in the body. The low capillary blood pressure also prevents rupture of the delicate respiratory membrane.

Figure 7. Lungs alveoli

Note: (a) Clusters of alveoli and their blood supply. (b) Structure of an alveolus. (c) Structure of the respiratory membrane.

How your lungs work

Your lungs have a system of tubes that carry oxygen in and out as you breathe. The windpipe divides into two tubes, the right bronchus and left bronchus. These split into smaller tubes called secondary bronchi. They split again to make smaller tubes called bronchioles. The bronchioles have small air sacs at the end called alveoli.

In the air sacs, oxygen passes into your bloodstream from the air breathed in. Your bloodstream carries oxygen to all the cells in your body. At the same time carbon dioxide passes from your bloodstream into the air sacs. This waste gas is removed from the body as you breathe out.

What are Lung Nodules?

A lung nodule (or mass) is a small abnormal area that is sometimes found during a CT scan of the chest. Most lung nodules seen on CT scans are not cancer. They are more often the result of old infections, scar tissue, or other causes. The risk of developing cancer in very small lung nodules (<5 mm) is very low 12. But tests are often needed to be sure a lung nodule is not cancer.

Most often the next step is to get a repeat CT scan of the chest to see if the lung nodule is growing over time. The time between scans might range anywhere from a few months to a year, depending on how likely your doctor thinks that the lung nodule could be cancer. This is based on the size, shape, and location of the lung nodule, as well as whether it appears to be solid or filled with fluid. If a repeat CT scan of the chest shows that the lung nodule has grown, your doctor might also want to get another type of imaging test called a positron emission tomography (PET) scan, which can often help tell if it is cancer.

If later scans show that the lung nodule has grown, or if the nodule has other concerning features, your doctor will want to get a sample of it to check it for cancer cells. This is called a biopsy. This can be done in different ways:

- The doctor might pass a long, thin tube called a bronchoscope, down your throat and into the airways of your lung to reach the nodule. A small tweezer on the end of the bronchoscope can be used to get a sample of the lung nodule.

- If the lung nodule is in the outer part of the lung, the doctor might pass a thin, hollow needle through the skin of the chest wall with the guidance of a CT scan and into the nodule to get a sample.

- If there is a higher chance that the nodule is cancer or if the nodule can’t be reached with a needle or bronchoscope, surgery might be done to remove the nodule and some surrounding lung tissue. Sometimes larger parts of the lung might be removed as well.

After a biopsy is done, the tissue sample will be looked at closely in the lab by a doctor called a pathologist. The pathologist will check the biopsy for cancer, infection, scar tissue, and other lung problems. If cancer is found, then special tests will be done to find out what kind of cancer it is. If something other than cancer is found, the next step will depend on the diagnosis. Some lung nodules will be followed with a repeat CT scan in 6-12 months for a few years to make sure it does not change. If the lung nodule biopsy shows an infection, you might be sent to a specialist called an infectious disease doctor, for further testing. Your doctor will decide on the next step, depending on the results of the biopsy.

Lung cancer signs and symptoms

Most lung cancers do not cause any symptoms until they have spread, but some people with early lung cancer do have symptoms. If you go to your doctor when you first notice symptoms, your cancer might be diagnosed at an earlier stage, when treatment is more likely to be effective.

Most of these symptoms are more likely to be caused by something other than lung cancer. Still, if you have any of these problems, it’s important to see your doctor right away so the cause can be found and treated, if needed.

The most common symptoms of lung cancer are:

- A cough that does not go away or gets worse

- Coughing up blood or rust-colored sputum (spit or phlegm)

- Chest pain that is often worse with deep breathing, coughing, or laughing

- Hoarseness of voice

- Loss of appetite

- Unexplained weight loss

- Shortness of breath

- Feeling tired or weak

- Infections such as bronchitis and pneumonia that don’t go away or keep coming back

- New onset of wheezing

- Some people have swollen fingers and nails called finger clubbing. They may also have pain and swelling in their joints. This condition is called hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy (HPOA).

If lung cancer spreads to other parts of the body, it may cause:

- Bone pain (like pain in the back or hips)

- Nervous system changes (such as headache, weakness or numbness of an arm or leg, dizziness, balance problems, or seizures), from cancer spread to the brain

- Yellowing of the skin and eyes (jaundice), from cancer spread to the liver

- Swelling of lymph nodes (collection of immune system cells) such as those in the neck or above the collarbone

Some lung cancers can cause syndromes, which are groups of specific symptoms.

Horner syndrome

Cancers of the upper part of the lungs are sometimes called Pancoast tumors. These tumors are more likely to be non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) than small cell lung cancer (SCLC).

Pancoast tumors can affect certain nerves to the eye and part of the face, causing a group of symptoms called Horner syndrome:

- Drooping or weakness of one upper eyelid (ptosis)

- A smaller pupil (dark part in the center of the eye) in the same eye (miosis)

- Little or no sweating on the same side of the face (anhidrosis)

Pancoast tumors can also sometimes cause severe shoulder pain.

Superior vena cava syndrome

The superior vena cava (SVC) is a large vein that carries blood from the head and arms down to the heart. It passes next to the upper part of the right lung and the lymph nodes inside the chest. Tumors in this area can press on the superior vena cava, which can cause the blood to back up in the veins. This can lead to swelling in the face, neck, arms, and upper chest (sometimes with a bluish-red skin color). It can also cause headaches, dizziness, and a change in consciousness if it affects the brain. While superior vena cava syndrome can develop gradually over time, in some cases it can become life-threatening, and needs to be treated right away.

Paraneoplastic syndromes

Some lung cancers make hormone-like substances that enter the bloodstream and cause problems with distant tissues and organs, even though the cancer has not spread to those places. These problems are called paraneoplastic syndromes. Sometimes paraneoplastic syndromes may be the first symptoms of lung cancer. Because the symptoms affect other organs, a disease other than lung cancer may first be suspected as causing them.

Paraneoplastic syndromes can happen with any lung cancer but are more often associated with small cell lung cancer (SCLC). Some common syndromes include:

- SIADH (syndrome of inappropriate anti-diuretic hormone): In this condition, the cancer cells make ADH (anti-diuretic hormone), a hormone that causes the kidneys to hold water. This lowers salt levels in the blood. Symptoms of syndrome of inappropriate anti-diuretic hormone (SIADH) can include fatigue, loss of appetite, muscle weakness or cramps, nausea, vomiting, restlessness, and confusion. Without treatment, severe cases may lead to seizures and coma.

- Cushing syndrome: In this condition, the cancer cells make ACTH, a hormone that causes the adrenal glands to make cortisol. This can lead to symptoms such as weight gain, easy bruising, weakness, drowsiness, and fluid retention. Cushing syndrome can also cause high blood pressure, high blood sugar levels, or even diabetes.

- Nervous system problems: Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) can sometimes cause the body’s immune system to attack parts of the nervous system, which can lead to problems. One example is a muscle disorder called Lambert-Eaton syndrome. In this syndrome, muscles around the hips become weak. One of the first signs may be trouble getting up from a sitting position. Later, muscles around the shoulder may become weak. A less common problem is paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration, which can cause loss of balance and unsteadiness in arm and leg movement, as well as trouble speaking or swallowing. Small cell lung cancer can also cause other nervous system problems, such as muscle weakness, sensation changes, vision problems, or even changes in behavior.

- High levels of calcium in the blood (hypercalcemia), which can cause frequent urination, thirst, constipation, nausea, vomiting, belly pain, weakness, fatigue, dizziness, and confusion

- Blood clots

Again, many of these symptoms are more likely to be caused by something other than lung cancer. Still, if you have any of these problems, it’s important to see your doctor right away so the cause can be found and treated, if needed.

Lung cancer causes

Smoking causes the majority of lung cancers — both in smokers and in people exposed to secondhand smoke. About 80% of lung cancer deaths are caused by smoking, and many others are caused by exposure to secondhand smoke. But lung cancer also occurs in people who never smoked and in those who never had prolonged exposure to secondhand smoke. In these cases, there may be no clear cause of lung cancer. People who smoke and are exposed to other known risk factors such as radon and asbestos are at an even higher risk.

Doctors believe smoking causes lung cancer by damaging the cells that line the lungs. When you inhale cigarette smoke, which is full of cancer-causing substances (carcinogens), changes in the lung tissue begin almost immediately. At first your body may be able to repair this damage. But with each repeated exposure, normal cells that line your lungs are increasingly damaged. Over time, the damage causes cells to act abnormally and eventually cancer may develop.

Workplace exposures to asbestos, diesel exhaust or certain other chemicals can also cause lung cancers in some people who don’t smoke.

A small portion of lung cancers develop in people with no known risk factors for the disease. Some of these might just be random events that don’t have an outside cause, but others might be due to factors that scientists don’t yet know about.

Lung cancers in people who don’t smoke are often different from those that occur in people who do. They tend to develop in younger people and often have certain gene changes that are different from those in tumors found in people who smoke. In some cases, these gene changes can be used to guide treatment.

Inherited gene changes

Some people inherit DNA mutations (changes) from their parents that greatly increase their risk for developing certain cancers. But inherited mutations alone are not thought to cause very many lung cancers. Still, genes do seem to play a role in some families with a history of lung cancer. For example, people who inherit certain DNA changes in a particular chromosome (chromosome 6) are more likely to develop lung cancer, even if they don’t smoke or only smoke a little.

Some people seem to inherit a reduced ability to break down or get rid of certain types of cancer-causing chemicals in the body, such as those found in tobacco smoke. This could put them at higher risk for lung cancer.

Other people inherit faulty DNA repair mechanisms that make it more likely they will end up with DNA changes. People with DNA repair enzymes that don’t work normally might be especially vulnerable to cancer-causing chemicals and radiation.

Some non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLCs) make too much EGFR protein (which comes from an abnormal EGFR gene). This specific gene change is seen more often with adenocarcinoma of the lung in young, non-smoking, Asian women, but the excess EGFR protein has also been seen in more than 60% of metastatic non-small cell lung cancers.

Researchers are developing tests that may help identify such people, but these tests are not yet used routinely. For now, doctors recommend that all people avoid tobacco smoke and other exposures that might increase their cancer risk.

Acquired gene changes

Gene changes related to lung cancer are usually acquired during a person’s lifetime rather than inherited. Acquired mutations in lung cells often result from exposure to factors in the environment, such as cancer-causing chemicals in tobacco smoke. But some gene changes may just be random events that sometimes happen inside a cell, without having an outside cause.

Acquired changes in certain genes, such as the RB1 tumor suppressor gene, are thought to be important in the development of small cell lung cancer (SCLC). Acquired changes in genes such as the p16 tumor suppressor gene and the K-RAS oncogene, are thought to be important in the development of non-small cell lung cancer. Changes in the TP53 tumor suppression gene and to chromosome 3 can be seen in both non-small cell lung cancer and small cell lung cancer. Not all lung cancers share the same gene changes, so there are undoubtedly changes in other genes that have not yet been found.

Risk factors for lung cancer

A number of factors may increase your risk of lung cancer. Some risk factors can be controlled, for instance, by quitting smoking. And other factors can’t be controlled, such as your family history.

Risk factors for lung cancer include:

- Smoking. Your risk of lung cancer increases with the number of cigarettes you smoke each day and the number of years you have smoked. Cigar smoking and pipe smoking are almost as likely to cause lung cancer as cigarette smoking. Smoking low-tar or “light” cigarettes increases lung cancer risk as much as regular cigarettes. Smoking menthol cigarettes might increase the risk even more since the menthol may allow people to inhale more deeply. Quitting at any age can significantly lower your risk of developing lung cancer.

- Exposure to secondhand smoke. Even if you don’t smoke, your risk of lung cancer increases if you’re exposed to secondhand smoke. Secondhand smoke is thought to cause more than 7,000 deaths from lung cancer each year.

- Previous radiation therapy. If you’ve undergone radiation therapy to the chest for another type of cancer, you may have an increased risk of developing lung cancer.

- Exposure to radon gas. Radon is produced by the natural breakdown of uranium in soil, rock and water that eventually becomes part of the air you breathe. Unsafe levels of radon can accumulate in any building, including homes. Homes and other buildings in nearly any part of the United States can have high indoor radon levels (especially in basements). According to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), radon is the second leading cause of lung cancer in this country, and is the leading cause among people who don’t smoke.

- Exposure to asbestos and other carcinogens. Workplace exposure to asbestos and other substances known to cause cancer — such as uranium, beryllium, cadmium, silica, vinyl chloride, nickel compounds, chromium compounds, coal products, mustard gas, chloromethyl ethers and diesel exhaust— can increase your risk of developing lung cancer, especially if you’re a smoker. Government and industry have taken steps in recent years to help protect workers from many of these exposures. But the dangers are still there, so if you work around these agents, be careful to limit your exposure whenever possible.

- Taking certain dietary supplements. Studies looking at the possible role of vitamin supplements in reducing lung cancer risk have had disappointing results. In fact, 2 large studies found that people who smoked who took beta carotene supplements actually had an increased risk of lung cancer. The results of these studies suggest that people who smoke should avoid taking beta carotene supplements.

- Arsenic in drinking water. Studies of people in parts of Southeast Asia and South America with high levels of arsenic in their drinking water have found a higher risk of lung cancer. In most of these studies, the levels of arsenic in the water were many times higher than those typically seen in the United States, even areas where arsenic levels are above normal. For most Americans who are on public water systems, drinking water is not a major source of arsenic.

- Air pollution. In cities, air pollution (especially near heavily trafficked roads) appears to raise the risk of lung cancer slightly. This risk is far less than the risk caused by smoking, but some researchers estimate that worldwide about 5% of all deaths from lung cancer may be due to outdoor air pollution.

- Family history of lung cancer. Brothers, sisters, and children of people who have had lung cancer may have a slightly higher risk of lung cancer themselves, especially if the relative was diagnosed at a younger age. It’s not clear how much of this risk might be due to shared genes among family members and how much might be from shared household exposures (such as tobacco smoke or radon). Researchers have found that genetics seems to play a role in some families with a strong history of lung cancer.

Lifetime chance of getting lung cancer

Overall, the chance that a man will develop lung cancer in his lifetime is about 1 in 17; for a woman, the risk is about 1 in 18 3. These numbers include both smokers and non-smokers. For smokers the risk is much higher, while for non-smokers the risk is lower.

Black men are about 12% more likely to develop lung cancer than White men 3. The rate is about 16% lower in Black women than in White women 3. Both black and white women have lower rates than men, but the gap is closing. The lung cancer rate has been dropping among men over the past few decades, but only for about the last decade in women 3.

Statistics on survival in people with lung cancer vary depending on the type of lung cancer, the stage (extent) of the cancer when it is diagnosed, and other factors.. For survival statistics based on the stage of the cancer, see Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Survival Rates By Stage.

Despite the very serious prognosis (outlook) of lung cancer, some people with earlier stage cancers are cured. More than 430,000 people alive today have been diagnosed with lung cancer at some point 3.

Lung cancer prevention

You can reduce your risk of lung cancer if you:

- Don’t smoke. If you’ve never smoked, don’t start. Talk to your children about not smoking so that they can understand how to avoid this major risk factor for lung cancer. Begin conversations about the dangers of smoking with your children early so that they know how to react to peer pressure.

- Stop smoking. Stop smoking now. Quitting reduces your risk of lung cancer, even if you’ve smoked for years. Talk to your healthcare team about strategies and aids that can help you quit. Options include nicotine replacement products, medicines and support groups.

- Avoid secondhand smoke. If you live or work with a person who smokes, urge them to quit. At the very least, ask them to smoke outside. Avoid areas where people smoke, such as bars. Seek out smoke-free options.

- Avoid carcinogens at work. Take precautions to protect yourself from exposure to toxic chemicals at work. Follow your employer’s precautions. For instance, if you’re given a face mask for protection, always wear it. Ask your healthcare professional what more you can do to protect yourself at work. Your risk of lung damage from workplace carcinogens increases if you smoke.

- Eat a diet full of fruits and vegetables. Choose a healthy diet with a variety of fruits and vegetables. Food sources of vitamins and nutrients are best. Avoid taking large doses of vitamins in pill form, as they may be harmful. For instance, researchers hoping to reduce the risk of lung cancer in people who smoked heavily gave them beta carotene supplements. Results showed the supplements increased the risk of cancer in people who smoke.

- Exercise most days of the week. If you don’t exercise regularly, start out slowly. Try to exercise most days of the week.

Tobacco smoke

Prevention offers the greatest opportunity to fight lung cancer. Although decades have passed since the link between smoking and lung cancers became clear, smoking is still responsible for most lung cancer deaths.

Quitting reduces your risk of lung cancer, even if you’ve smoked for years. Talk to your doctor about strategies and stop-smoking aids that can help you quit. Options include nicotine replacement products, medications and support groups.

Avoid secondhand smoke. If you live or work with a smoker, urge him or her to quit. At the very least, ask him or her to smoke outside. Avoid areas where people smoke, such as bars and restaurants, and seek out smoke-free options.

Environmental causes

Researchers also continue to look into some of the other causes of lung cancer, such as exposure to radon and diesel exhaust. Finding new ways to limit these exposures could potentially save many more lives.

Test your home for radon. Have the radon levels in your home checked, especially if you live in an area where radon is known to be a problem. High radon levels can be remedied to make your home safer. For information on radon testing, contact your local department of public health or a local chapter of the American Lung Association.

Avoid carcinogens at work. Take precautions to protect yourself from exposure to toxic chemicals at work. Follow your employer’s precautions. For instance, if you’re given a face mask for protection, always wear it. Ask your doctor what more you can do to protect yourself at work. Your risk of lung damage from workplace carcinogens increases if you smoke.

Healthy Diet, Nutrition, and Lifestyle

Researchers are looking for ways to use vitamins or medicines to prevent lung cancer in people at high risk, but so far none have been shown to clearly reduce risk.

Some studies have suggested that a diet high in fruits and vegetables may offer some protection, but more research is needed to confirm this. While any protective effect of fruits and vegetables on lung cancer risk is likely to be much smaller than the increased risk from smoking, following the American Cancer Society dietary recommendations (such as staying at a healthy weight and eating a diet high in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains) may still be helpful.

Avoid taking large doses of vitamins in pill form, as they may be harmful. For instance, researchers hoping to reduce the risk of lung cancer in heavy smokers gave them beta carotene supplements. Results showed beta-carotene supplements actually increased the risk of lung cancer in smokers. The Carotene and Retinol Efficacy Trial 13 included 18,314 male and female current and former smokers (with at least a 20 pack-year history [equivalent to smoking 1 pack per day for 20 years or 2 packs per day for 10 years, for example] of cigarette smoking), as well as some men occupationally exposed to asbestos (who also have a higher risk of lung cancer), all aged 45–74 years. The study randomized participants to take supplements containing 30 mg beta-carotene plus 25,000 IU (7,500 mcg RAE) retinyl palmitate or a placebo daily for about 6 years to evaluate the potential effects on lung cancer risk 13. The trial was ended prematurely after a mean of 4 years, partly because the supplements were unexpectedly found to have increased lung cancer risk by 28% and death from lung cancer by 46%; the supplements also increased the risk of all-cause mortality by 17%. A subsequent study followed the Carotene and Retinol Efficacy Trial participants for an additional 6 years after they stopped taking the study supplements 14. During this time, the differences in lung cancer risk between the intervention and placebo groups were no longer statistically significant, with one exception: women in the intervention group had a 33% higher risk of lung cancer 14.

Exercise most days of the week. A meta-analysis of leisure-time physical activity and lung cancer risk revealed that higher levels of physical activity protect against lung cancer 15. The overall evidence for physical activity has been mixed, but several studies have reported that individuals who are more physically active have a lower risk of lung cancer than those who are more sedentary, even after adjustment for cigarette smoking 16, 17. The American Institute for Cancer Research evidence review rated the inverse association between physical activity and lung cancer as limited suggestive evidence 18.

Early detection

As mentioned in lung cancer screening, screening with low dose spiral CT (LDCT) scans in people at high risk of lung cancer (due to smoking history) lowers the risk of death from lung cancer, when compared to chest x-rays 19. Lung cancer screening is generally offered to older adults who have smoked heavily for many years or who have quit in the past 15 years.

Another approach now being studied uses newer, sensitive tests to look for cancer cells in sputum samples 20. Researchers have found several changes often seen in the DNA of lung cancer cells. Studies are looking at tests that can spot these DNA changes to see if they can find lung cancers at an earlier stage.

Lung cancer screening

Screening is meant to find cancer in people who do not have symptoms of the disease. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) makes recommendations about the effectiveness of specific preventive care services for patients without related signs or symptoms 21.

It U.S. Preventive Services Task Force bases its recommendations on the evidence of both the benefits and harms of the service and an assessment of the balance. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force does not consider the costs of providing a service in this assessment.

In 2021, the USPSTF recommends annual screening for lung cancer with low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) in adults aged 50 to 80 years who have a 20 pack-year smoking history and currently smoke or have quit within the past 15 years 22. Screening should be discontinued once a person has not smoked for 15 years or develops a health problem that substantially limits life expectancy or the ability or willingness to have curative lung surgery 22.

For low-dose computed tomography (LDCT), you lie on a thin, flat table that slides back and forth inside the hole in the middle of the CT scanner, which is a large, doughnut-shaped machine. As the table moves into the opening, an x-ray tube rotates within the scanner, sending out many tiny x-ray beams at precise angles. These beams quickly pass through your body and are detected on the other side of the scanner. A computer then converts these results into detailed images of the lungs.

The main benefit of screening is finding the cancer earlier and thus, lowering the chance of dying from lung cancer.

As with any type of screening, it’s important to be aware that, not everyone who gets screened will benefit. Screening with LDCT will not find all lung cancers. Not all of the cancers that are found will be found at an early stage. Some people with lung cancer that is found by screening will still die from that cancer.

Low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) scans can also find things that turn out not to be cancer, but that still have to be checked out with more tests to know what they are. You might need more CT scans, or less often, invasive tests such as a lung biopsy, in which a piece of lung tissue is removed with a needle or during surgery. These tests may lead to serious complications, but they rarely do.

Low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) scans also expose people to a small amount of radiation with each test. It is less than the dose from a standard CT, but it is more than the dose from a chest x-ray. Some people who are screened may end up needing further CT scans, which means more radiation exposure.

American Cancer Society’s guidelines for lung cancer screening

The American Cancer Society has thoroughly reviewed the subject of lung cancer screening and issued guidelines that are aimed at doctors and other health care providers 23:

The American Cancer Society recommends yearly screening for lung cancer with a low-dose CT (LDCT) scan for people ages 50 to 80 years who 24:

- Smoke or used to smoke

- AND

- Have at least a 20 pack-year history of smoking

A pack-year is equal to smoking 1 pack (or about 20 cigarettes) per day for a year. For example, a person could have a 20 pack-year history by smoking 1 pack a day for 20 years, or by smoking 2 packs a day for 10 years.

Before deciding to be screened, people should have a discussion with a health care professional about the purpose of screening and how it is done, as well as the benefits, limits, and possible harms of screening.

People who still smoke should be counseled about quitting and offered interventions and resources to help them.

People should not be screened if they have serious health problems that will likely limit how long they will live, or if they won’t be able to or won’t want to get treatment if lung cancer is found.

To get the most benefit from screening, patients need to be in good health. For example, they need to be able to have surgery and other treatments to try to cure lung cancer if it is found. Patients who need home oxygen therapy probably couldn’t withstand having part of a lung removed, and so are not candidates for screening. Patients with other serious medical problems that would shorten their lives or keep them from having surgery might not benefit enough from screening for it to be worth the risks, and so should also not be screened.

Metal implants in the chest (like pacemakers) or back (like rods in the spine) can interfere with x-rays and lead to poor quality CT images of the lungs. People with these types of implants were also kept out of the National Lung Screening Trial, and so should not be screened with CT scans for lung cancer according to the American Cancer Society guidelines.

Doctors should talk to these patients about the benefits, limitations, and potential harms of lung cancer screening. Screening should only be done at facilities that have the right type of CT scanner and that have a lot of experience using low-dose CT scans for lung cancer screening. The facility should also have a team of specialists that can provide the appropriate care and follow-up of patients with abnormal results on the scans.

If you and your doctor decide that you should be screened, you should get a low-dose CT scan every year until you reach the age of 74, as long as you are still in good health.

Lung cancer complications

Some people with lung cancer will develop symptoms, such as shortness of breath, a cough and/or chest pain, because of how the cancer affects the lung’s function. As it advances, lung cancer may cause other complications. These can include fluid build-up in the space around your lung (pleural effusion). Lung cancer can also affect your appetite and you may lose weight. You may feel very fatigued and/or have difficulty sleeping.

You may also experience these symptoms and others as side effects of lung-cancer treatments.

Your medical team has a lot of experience in treating symptoms and complications of lung cancer and can give you advice and support to manage them.

Even if you are receiving cancer treatment, there is still a chance that your cancer can spread to another part of your body (metastasis). If this happens, you and your medical team may adjust your cancer treatment plan.

Lung cancer can cause complications, such as:

- Shortness of breath. People with lung cancer can experience shortness of breath if cancer grows to block the major airways. Lung cancer can also cause fluid to accumulate around the lungs, making it harder for the affected lung to expand fully when you inhale.

- Coughing up blood. Lung cancer can cause bleeding in the airway, which can cause you to cough up blood (hemoptysis). Sometimes bleeding can become severe. Treatments are available to control bleeding.

- Pain. Advanced lung cancer that spreads to the lining of a lung or to another area of the body, such as a bone, can cause pain. Tell your doctor if you experience pain, as many treatments are available to control pain.

- Fluid in the chest (pleural effusion). Lung cancer can cause fluid to accumulate in the space that surrounds the affected lung in the chest cavity (pleural space). Fluid accumulating in the chest can cause shortness of breath. Treatments are available to drain the fluid from your chest and reduce the risk that pleural effusion will occur again.

- Cancer that spreads to other parts of the body (metastasis). Lung cancer often spreads (metastasizes) to other parts of the body, such as the brain and the bones. Cancer that spreads can cause pain, nausea, headaches, or other signs and symptoms depending on what organ is affected. Once lung cancer has spread beyond the lungs, it’s generally not curable. Treatments are available to decrease signs and symptoms and to help you live longer.

Lung cancer diagnosis

If there’s reason to think that you may have lung cancer, your doctor can order a number of tests to look for cancerous cells and to rule out other conditions.

Tests may include:

- Imaging tests. An X-ray image of your lungs may reveal an abnormal mass or nodule. A CT scan can reveal small lesions in your lungs that might not be detected on an X-ray. MRI scans are most often used to look for possible spread of lung cancer to the brain or spinal cord. Positron emission tomography (PET) scan a slightly radioactive form of sugar (known as FDG) is injected into the blood and collects mainly in cancer cells.

- Sputum cytology. If you have a cough and are producing sputum, looking at the sputum under the microscope can sometimes reveal the presence of lung cancer cells. The best way to do this is to get early morning samples 3 days in a row. This test is more likely to help find cancers that start in the major airways of the lung, such as squamous cell lung cancers. It might not be as helpful for finding other types of lung cancer. If your doctor suspects lung cancer, further testing will be done even if no cancer cells are found in the sputum.

- Tissue sample (biopsy). A sample of abnormal cells may be removed in a procedure called a biopsy. Your doctor can perform a biopsy in a number of ways, including bronchoscopy, in which your doctor examines abnormal areas of your lungs using a lighted tube that’s passed down your throat and into your lungs. Mediastinoscopy, in which an incision is made at the base of your neck and surgical tools are inserted behind your breastbone to take tissue samples from lymph nodes is also an option. Another option is needle biopsy, in which your doctor uses X-ray or CT images to guide a needle through your chest wall and into the lung tissue to collect suspicious cells. A biopsy sample may also be taken from lymph nodes or other areas where cancer has spread, such as your liver.

Careful analysis of your cancer cells in a lab will reveal what type of lung cancer you have. Results of sophisticated testing can tell your doctor the specific characteristics of your cells that can help determine your prognosis and guide your treatment.

Molecular tests for gene changes

In some cases, especially for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), doctors may test for specific gene changes in the cancer cells that could mean certain targeted drugs might help treat the cancer. For example:

- About 20% to 25% of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) have changes in the KRAS gene that cause them to make an abnormal KRAS protein, which helps the cancer cells grow and spread. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with this mutation are often adenocarcinomas, resistant to other drugs such as EGFR inhibitors, and are most often found in people with a smoking history.

- EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor) is a protein that appears in high amounts on the surface of 10% to 20% of NSCLC cells and helps them grow. Some drugs that target EGFR can be used to treat NSCLC with changes in the EGFR gene, which are more common in certain groups, such as those who don’t smoke, women, and Asians. But these drugs don’t seem to be as helpful in patients whose cancer cells have changes in the KRAS gene.

- About 5% of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) have a change in the ALK gene. This change is most often seen in people who don’t smoke (or who smoke lightly) and have the adenocarcinoma subtype of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Doctors may test cancers for changes in the ALK gene to see if drugs that target this change may help them.

- About 1% to 2% of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) have a rearrangement in the ROS1 gene, which might make the tumor respond to certain targeted drugs.

- A small percentage of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) have changes in the RET gene. Certain drugs that target cells with RET gene changes might be options for treating these tumors.

- About 5% of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) have changes in the BRAF gene. Certain drugs that target cells with BRAF gene changes might be an option for treating these tumors.

- A small percentage of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) have certain changes in the MET gene that make them more likely to respond to some targeted drugs.

- In a small percentage of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), the cancer cells have certain changes in the HER2 gene that make them more likely to respond to a targeted drug.

- A small number of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) have changes in one of the NTRK genes that make them more likely to respond to some targeted drugs.

These genetic tests can be done on tissue taken during a biopsy or surgery for lung cancer. If the biopsy sample is too small and all the studies cannot be done, the testing may also be done on blood that is taken from a vein just like a regular blood draw. This blood contains the DNA from dead tumor cells found in the bloodstream of people with advanced lung cancer. Obtaining the tumor DNA through a blood draw is called a “liquid biopsy”. Liquid biopsies are done in cases where a tissue biopsy is not possible or if a tissue biopsy is felt to be too dangerous for the patient.

Tests for certain proteins on tumor cells

Lab tests might also be done to look for certain proteins on the cancer cells. For example, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells might be tested for the PD-L1 (program death ligand 1) protein, which can show if the cancer is more likely to respond to treatment with certain immunotherapy drugs.

Lung cancer grades

Grading is a way of dividing cancer cells into groups based on how the cells look under a microscope. This gives your doctors an idea of how quickly or slowly the cancer might grow and whether it is likely to spread.

For most lung cancers, there isn’t a specific grading system doctors use. But generally:

- Grade 1: The cells look very like normal cells. They tend to be slow growing and are less likely to spread than higher grade cancer cells. They are called low grade.

- Grade 2: The cells look more abnormal and are more likely to spread. This grade is also called moderately well differentiated or moderate grade.

- Grades 3 and 4: The cells look very abnormal and not like normal cells. They tend to grow quickly and are more likely to spread. They are called poorly differentiated or high grade.

Lung cancer staging

Once your lung cancer has been diagnosed, your doctor will work to determine the stage (extent) of your cancer. The stage of a cancer tells you how big it is and whether it has spread. Your cancer’s stage helps you and your doctor decide what treatment is most appropriate. For example, the best treatment for an early-stage cancer may be surgery or radiation, while a more advanced-stage cancer may need treatments that reach all parts of the body, such as chemotherapy, targeted drug therapy, or immunotherapy.