Contents

- What is varicella

- Chickenpox in pregnancy

- Congenital varicella syndrome

- My due date is in 3 weeks, and I have just been exposed to chickenpox. Is there any risk to my baby if I develop chickenpox at this stage of pregnancy?

- Does getting chickenpox in pregnancy cause long-term problems in behavior or learning for the baby?

- Can I breastfeed while sick with chickenpox?

- What is the cause of chickenpox?

- Chickenpox prevention

- Chickenpox vaccine

- What are the side effects of the chickenpox vaccine (varicella vaccine)?

- How effective is the varicella vaccine?

- Who should NOT get chickenpox vaccine

- Duration of chickenpox vaccine protection

- Varicella vaccine cost

- Chickenpox vaccine near me

- My daughter had chickenpox at 10 months old, but now that she is 1 year old, her doctor said she should still get the chickenpox vaccine. Is this really necessary?

- If we immunize children against chickenpox, will they be more likely to develop shingles later in life?

- If we immunize children with the varicella vaccine, won’t they be more likely to get chickenpox as adults?

- Should teenagers and adults get the varicella vaccine?

- I got the chickenpox vaccine as an adult, but I got a fever and a rash, so should I get the second dose of chickenpox vaccine?

- Chickenpox signs and symptoms

- Chickenpox stages

- Complications of chickenpox

- Chickenpox diagnosis

- Chickenpox treatment

- Chickenpox prognosis

What is varicella

Varicella also known as chickenpox is a highly contagious viral infection caused by the first time infection (primary infection) with the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) of the herpes family 1. The varicella-zoster virus (VZV) is sometimes called herpesvirus type 3 and is a member of the alpha herpesviridiae order of double-stranded DNA viruses 2. Most chickenpox cases are in children under age 10, but older children and adults of all races and sex can get it. Adult with chickenpox are more likely to have life-threatening complications than children with chickenpox, such as thrombocytopenia (low blood platelets), viral pneumonia, disseminated primary varicella infection with inflammation of the internal organs of the body such as liver inflammation (hepatitis), lung inflammation (pneumonitis) and brain inflammation (encephalitis), Reye syndrome and Guillain-Barré syndrome, which could be life-threatening especially in adults with weakened immune system 3. Careful follow-up is required when an adult is diagnosed with adult chickenpox 4.

Varicella–zoster virus (VZV) causes 2 distinct syndromes 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10:

- First time infection also known as “primary infection” with the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) presents as varicella or chickenpox, a highly contagious and usually benign illness that occurs in epidemics among susceptible children where the symptoms in most children usually cease within one or two weeks as a result of host immunity. After the first-time infection (primary infection) with the varicella-zoster virus (VZV), the virus lies dormant in dorsal root or cranial nerve ganglia of nearly all individuals after the chickenpox resolves 11. However, in some people with uncommon severe infections, the complications could result in inflammation of the internal organs of the body, including liver inflammation (hepatitis), lung inflammation (pneumonitis) and brain inflammation (encephalitis), which could be life-threatening, especially in immunocompromised individuals 12, 13. Despite that most global populations are vaccinated in childhood with varicella (chickenpox) vaccine, approximately 1.5 million hospitalizations and 30,000 deaths due to varicella-zoster virus (VZV)-related diseases are estimated to occur worldwide annually 14.

- Reactivation of latent varicella–zoster virus (VZV) in dorsal-root ganglia (clusters of sensory nerve cell bodies that transmit sensory information from your body to your spinal cord) or in the cranial nerve (especially in older adults and individuals with weak immune systems) results in a localized skin eruption termed “herpes zoster” or “shingles” 10, 15. A typical history for herpes zoster (shingles) might include nerve (neuropathic) pain for around three days followed by a vesicular rash (small fluid-filled blisters) in a dermatomal distribution (areas of skin whose sensory distribution is innervated by a specific afferent nerve fibers from the dorsal root of a specific single spinal nerve) 16, 6. The rash takes around two weeks to resolve and can scar. It is not clear why herpes zoster (shingles) affects a particular nerve fiber. Triggering factors are sometimes recognized, such as: pressure on the nerve roots, radiation therapy at the level of the affected nerve root, spinal surgery, an infection, an injury (not necessarily to the spine) or contact with someone with varicella or herpes zoster. The overall lifetime risk of herpes zoster (shingles) is 32.2% 17 and postherpetic neuralgia affects 13–25% of patients with herpes zoster 18. Post-herpetic neuralgia (PHN) is the most common complication and is more likely in older people, where it can take six months or more to resolve. Post-herpetic neuralgia is a type of nerve (neuropathic) pain that occurs after a shingles (herpes zoster) outbreak. Post-herpetic neuralgia is a burning, sharp, or aching pain that lasts for at least 90 days after the shingles rash appears. The pain is usually limited to the area where the shingles rash was located, such as around the chest or abdomen. Post-herpetic neuralgia (PHN) can also cause itching, numbness, tiredness, trouble sleeping, decreased appetite, and poor concentration. The risk of developing post-herpetic neuralgia increases with age, and people with weakened immune systems are also at higher risk. Many people with post-herpetic neuralgia make a full recovery within a year, but symptoms can sometimes last for several years or be permanent.

People develop symptoms about 7-21 days after being exposed to chickenpox. The classic symptom of chickenpox is an uncomfortable, itchy rash. The rash turns into fluid-filled blisters (vesicles) and eventually into scabs. It usually shows up on the face, chest, and back and then spreads to the rest of the body. Other symptoms include:

- Fever

- Headache

- Tiredness

- Loss of appetite

Sometimes children who have been vaccinated develop chickenpox. In these children, the rash is typically milder, fever is less common, and the illness is shorter. However, contact with the sores can spread the infection.

When exposed to the rash, a person can develop the disease in 14-21 days. Generally, the symptoms that are seen are an itchy rash with vesicular (fluid filled) lesions. Prior to chickenpox vaccine, the average was 250-500 lesions in varying stages of development during the course of illness. The lesions go though papules (flattened lesions) to vesicles (fluid filled), and then to resolution (crusting). Generally, these are seen with a low grade fever. The lesions put the person at higher risk for local infection to the affected areas on their skin. People can develop more symptoms that affect the whole body and can cause major illness. Prior to widespread vaccinating, each year, chickenpox caused about 4 million cases, about 10,600 hospitalizations and 100 to 150 deaths in the US from varicella. During the first 25 years of the U.S. chickenpox vaccination program, the vaccine has prevented an estimated 91 million cases, 238,000 hospitalizations, and 2,000 deaths.

In otherwise healthy children, chickenpox typically needs no medical treatment. Chickenpox in children is usually mild and lasts 5 to 10 days. Children should not scratch the blisters because it could lead to secondary bacterial infections. Keep fingernails short to decrease the likelihood of scratching. Calamine lotions and oatmeal baths can help with itching. Your doctor may prescribe an antihistamine to relieve itching. Acetaminophen (paracetamol) can treat the fever. Children with chickenpox should NEVER be given aspirin; that combination can cause Reye syndrome.

Treatment for chickenpox may include:

- Acetaminophen (to reduce fever). Children with chickenpox should NEVER be given aspirin.

- Skin lotion (to relieve itchiness) e.g. Calamine lotion

- Antiviral drugs (for severe cases)

- Bed rest

- Drinking plenty of fluids (to prevent dehydration)

- Cool baths with baking soda (to relieve itching)

Chickenpox can sometimes cause serious problems. Adults, babies, teenagers, pregnant women, and those with weak immune systems tend to get sicker from it. For people who are at high risk of complications from chickenpox, doctors sometimes prescribe antiviral medicines to shorten the length of the infection and to help reduce the risk of complications.

Complications from chickenpox are more common in adults and people with weak immune systems. Complications may include:

- Secondary bacterial infections

- Pneumonia (lung infections)

- Encephalitis (inflammation of the brain)

- Cerebellar ataxia (defective muscular coordination)

- Transverse myelitis (inflammation along the spinal cord)

- Reye syndrome. This is a serious condition marked by a group of symptoms that may affect all major systems or organs. Do not give aspirin to children with chickenpox. It increases the risk for Reye syndrome.

- Death

If you or your child are at high risk of complications, your doctor may suggest an antiviral drug such as acyclovir (Zovirax, Sitavig). This medication might lessen the severity of chickenpox when given within 24 hours after the rash first appears. Other antiviral drugs, such as valacyclovir (Valtrex) and famciclovir, also may lessen the severity of the disease, but might not be approved or appropriate for everyone.

In some instances, your doctor may recommend getting the chickenpox vaccine within three to five days after you’ve been exposed to the virus. This can prevent the disease or lessen its severity.

If complications develop, your doctor will determine the appropriate treatment. He or she may prescribe antibiotics for skin infections and pneumonia. Brain inflammation (encephalitis) is usually treated with antiviral drugs. You may need to be hospitalized.

Once you catch chickenpox, the virus usually stays in your body. You probably will not get chickenpox again, but the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) can cause shingles (herpes zoster) in adults. A chickenpox vaccine can help prevent most cases of chickenpox, or make it less severe if you do get it.

Figure 1. Chickenpox rash (varicella rash) on a child

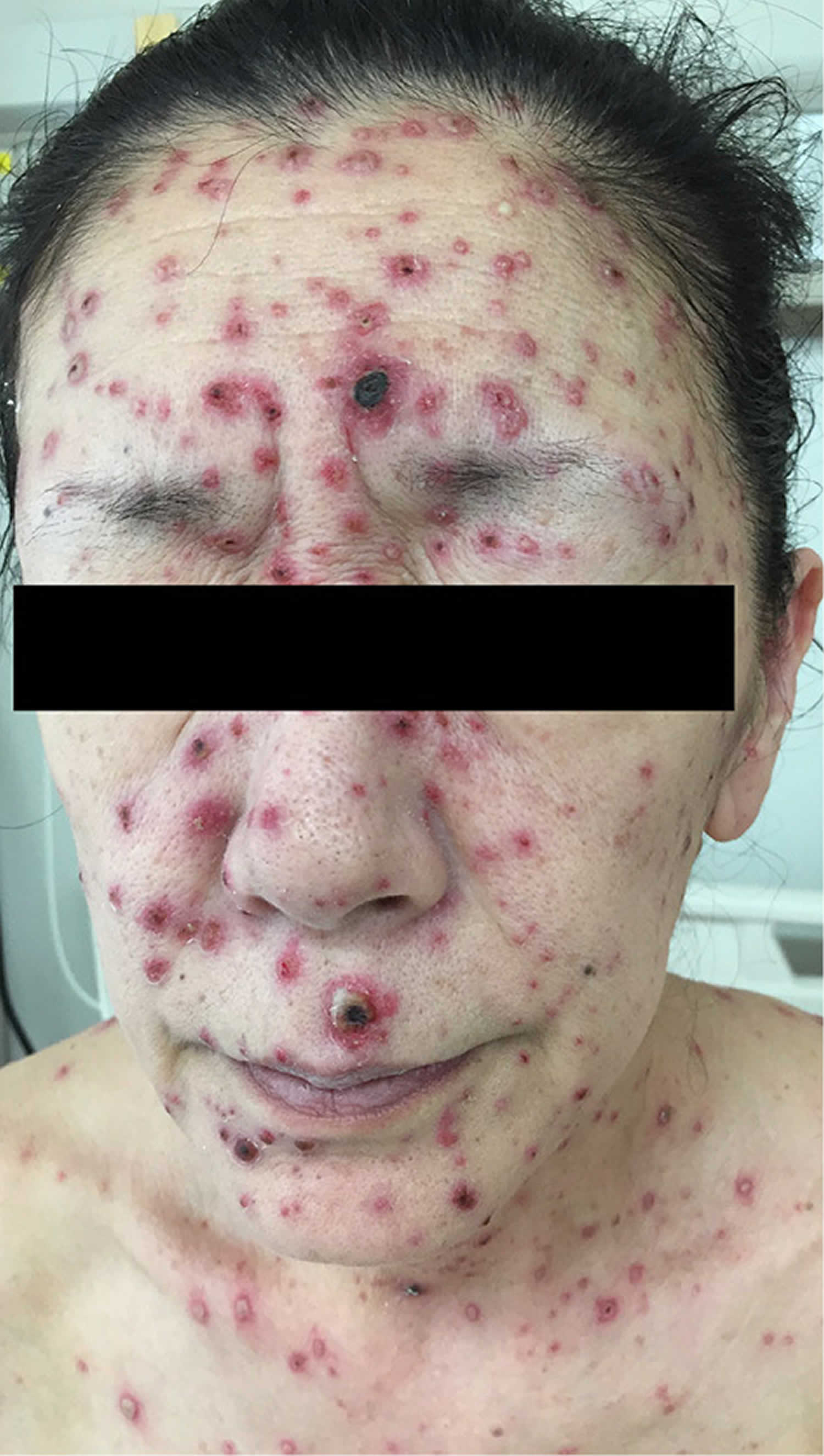

Figure 2. Chickenpox in adults

[Source 4 ]Figure 3. Shingles (herpes zoster)

Footnotes: Shingles also called herpes zoster is caused by reactivation of a primary infection with varicella zoster virus (VZV) that resides in the sensory ganglia and dorsal nerve roots after primary infection with varicella zoster virus (VZV), especially in older adults and immunocompromised individuals. Shingles (herpes zoster) primarily manifests as a painful skin rash and blisters occurring in specific dermatomes (areas of skin that connect to a specific nerve root on your spine), which are called “zoster” herpes. Panel A shows herpes zoster in the ophthalmic (V1) branch of the trigeminal ganglia. Panel B shows vesicles and pustules in a patient with herpes zoster.

[Source 10 ]Figure 4. Herpes zoster (shingles)

Footnotes: Herpes zoster also called shingles is caused by reactivation of a primary infection with varicella zoster virus (VZV).

[Source 19 ]Figure 5. Ophthalmic herpes zoster

Footnote: Vesicular lesions developed over the V1 distribution of the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve 5) in this patient with acute herpes zoster. Lesions on the tip of her nose suggest involvement of the nasociliary nerve that supplies the globe.

How contagious is chickenpox?

Chickenpox is very contagious. If 100 people are sitting in a room together for several hours talking and one of them has chickenpox and the other 99 have never been infected with chickenpox or vaccinated with the chickenpox vaccine, about 85 of the remaining 99 will get chickenpox.

Chicken pox incubation period

The incubation period for varicella-zoster virus (VZV) is typically between 10 to 21 days. Patients with chickenpox are considered contagious from 1 to 2 days before developing the rash until all skin lesions have crusted over. This may take 5–10 days. Varicella infection in pregnant women can spread via the placenta and infect the fetus 20, 21.

Chickenpox contagious period

A person with chickenpox is contagious 1–2 days before the rash appears and until all the blisters have formed scabs. This may take 5–10 days. Children should stay away from school or childcare facilities throughout this contagious period. Adults with chickenpox who work among children should also remain home.

It can take 10–21 days after contact with an infected person for someone to develop chickenpox. This is how long it takes for the virus to replicate and come out in the characteristic rash in the new host.

As chickenpox may cause complications in immunocompromised individuals and pregnant women, these people should avoid visiting friends or family when there is a known case of chickenpox. In cases of inadvertent contact, see your doctor who may prescribe special preventive treatment.

If I had chickenpox can I get shingles?

Yes. Anyone who has had chickenpox or varicella may subsequently develop shingles 13. Shingles also called herpes zoster is a localized, blistering and painful rash caused by reactivation of varicella-zoster virus (VZV). Shingles (herpes zoster) often affects people with weak immunity. Shingles can occur in childhood but is much more common in adults, especially older people. People with various kinds of cancer have a 40% increased risk of developing shingles. The overall lifetime risk of shingles (herpes zoster) is 32.2% 17 and postherpetic neuralgia affects 13–25% of patients with herpes zoster 18. People who have had shingles rarely get it again; the chance of getting a second episode is about 1%.

If you never had chickenpox can you get shingles?

No. Shingles or herpes zoster is caused by reactivation of latent varicella–zoster virus (VZV) in the dorsal-root ganglia (clusters of sensory nerve cell bodies that transmit sensory information from your body to your spinal cord) or in the cranial nerve especially in older adults and individuals with weak immune systems 22, 23, 10, 15. Varicella zoster virus (VZV) causes chickenpox and can remain inactive in your nerve cells for many years. After primary infection (first-time infection) with varicella–zoster virus (VZV), the virus remains dormant in dorsal root ganglia nerve cells in your spine for years. The virus can reactivate, travel through the nerve to your skin, and produce blisters along the nerve path. This condition is called shingles (herpes zoster), and mostly affects people with low immunity, such as older people. Before blisters appear, symptoms may include itching, numbness, tingling, or local pain. Shingles causes nerve inflammation and severe pain that can affect quality of life. The incidence rate of herpes zoster ranges from 2.08 cases to 6.20 cases per 1000 person‐years (i.e. the number of new cases per population at risk, in a given time period). This number is increasing, due in part to people living longer 24.

How can I find out if I am infected with varicella?

Your doctor can do a blood test to find out if you have a current infection with chickenpox. They can also test to see if you have ever had chickenpox in the past. When a person has chickenpox, they make antibodies to the virus. These antibodies usually last a long time and keep a person from getting chickenpox again. (The person becomes immune.) People who are immune are not likely to develop chickenpox if they are exposed to the virus again.

The most sensitive method for confirming a diagnosis of varicella is the use of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to detect varicella-zoster virus (VZV) in skin lesions (vesicles, scabs, maculopapular lesions). Vesicular lesions or scabs, if present, are the best for sampling. Adequate collection of specimens from maculopapular lesions in vaccinated people can be challenging. However, one study comparing a variety of specimens from the same patients vaccinated with one dose suggests that maculopapular lesions collected with proper technique can be highly reliable specimen types for detecting varicella-zoster virus (VZV). Other sources such as nasopharyngeal secretions, saliva, urine, bronchial washings, and cerebrospinal fluid are less likely to provide an adequate sample and can often lead to false negative results.

Other viral isolation techniques for confirming varicella are direct fluorescent antibody assay (DFA) and viral culture. However, these techniques are generally not recommended because they are less sensitive than PCR and, in the case of viral culture, will take longer to generate results.

IgM serologic testing is considerably less sensitive than PCR testing of skin lesions. IgM serology can provide evidence for a recent active varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infection, but cannot discriminate between a primary infection and reinfection or reactivation from latency since specific IgM antibodies are transiently produced on each exposure to varicella-zoster virus (VZV). IgM tests are also inherently prone to poor specificity.

Paired acute and convalescent sera showing a four-fold rise in IgG antibodies have excellent specificity for varicella, but are not as sensitive as PCR of skin lesions for diagnosing varicella. People with prior history of vaccination or disease history may have very high baseline titers, and may not achieve a four-fold increase in the convalescent sera. The usefulness of this method for diagnosing varicella is further limited as it requires two office visits. A single positive IgG ELISA result cannot be used to confirm a varicella case.

If you have recently been around someone with chickenpox and you do not have immunity, talk to your doctor about what steps you can take to avoid getting chickenpox, or to reduce the severity of the symptoms.

Chickenpox in pregnancy

Non-immune pregnant women should take care to avoid contact with people who have chickenpox and to wash their hands frequently when handling food, animals, and children. Exposure to the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) in pregnancy (chickenpox in the first half of pregnancies) may cause viral pneumonia, premature labor and preterm delivery (delivery before 37 weeks of pregnancy) and rarely maternal death. About 2% of babies (1 in 50) of a pregnant person with chickenpox will have 1 or more birth defects due to the infection 25. 1% (1/100) of pregnancies that are infected with chickenpox in the first trimester have birth defects related to chickenpox (and 99% do not). When chickenpox occurs between 13 and 20 weeks of pregnancy, the chance for birth defects related to the chickenpox infection is to 2% (98% of pregnancies do not have related birth defects) 25. The chance for birth defects is greatest when chickenpox develops between 7 and 20 weeks of pregnancy 25.

Babies with birth defects from exposure to chickenpox in pregnancy are said to have congenital varicella syndrome. The birth defects include scars on the skin, eye problems (fetal chorioretinitis & cataracts), poor growth, underdevelopment of an arm or leg (limb atrophy), small head size (microcephaly), or delayed development and/or intellectual disability. Some babies may have only one of these problems while others have some or all. However, most babies born to women who have chickenpox in pregnancy are healthy 25.

If a mother develops chickenpox just before delivery or during the 28 days after delivery, her baby is at risk of severe infection. Chickenpox infection in this time period is called neonatal varicella. For infants with neonatal varicella infection, if untreated, the mortality rate is as high as 31%. Death typically occurs from varicella pneumonia. The mortality rate decreases to 7% when varicella-zoster immune globulin (VariZIG) is administered 20, 26.

Approximately 25% of fetuses of mothers with chickenpox become infected. It is harmless to most of them. Offspring may remain asymptomatic, or develop herpes zoster (shingles) at a young age without a previous history of primary chickenpox infection. They may also develop congenital varicella syndrome, one of the TORCH infections.

Congenital varicella syndrome

Congenital varicella syndrome occurs in up to 2% of fetuses exposed to varicella-zoster virus (VZV) in the first 20 weeks of gestation. It can result in spontaneous abortion, fetal chorioretinitis, cataracts, limb atrophy (underdevelopment of an arm or leg), cerebral cortical atrophy and microcephaly (small head size), skin scars, and delayed development and/or intellectual disability. The overall prognosis of infants born with congenital varicella syndrome is poor, often fatal in roughly 30% of infected babies within the first month of life 27. Death in infancy often results from intractable gastrointestinal reflux, severe recurrent aspiration pneumonia, and respiratory failure 21, 28.

My due date is in 3 weeks, and I have just been exposed to chickenpox. Is there any risk to my baby if I develop chickenpox at this stage of pregnancy?

If you already had chickenpox or had the varicella vaccine, your past infection or vaccine should protect you. If you have not had chickenpox or the varicella vaccine, talk to your healthcare provider right away. If you develop chickenpox 5 days or less before delivery or 1-2 days after delivery, there is a 20-25% chance your newborn could also develop chickenpox. Chickenpox infection in this time period is called neonatal varicella. For infants with neonatal varicella infection, if untreated, the mortality rate is as high as 31%. Death typically occurs from varicella pneumonia. The mortality rate decreases to 7% when varicella-zoster immune globulin (VariZIG) is administered 20, 26.

If you develop chickenpox between 6 and 21 days before delivery, there is still a chance your newborn could develop neonatal varicella. However, because your baby will get some of your newly-made chickenpox antibodies, the neonatal varicella is more likely to be mild.

Does getting chickenpox in pregnancy cause long-term problems in behavior or learning for the baby?

Most babies born to a person who had chickenpox in pregnancy are healthy. However, some children could have eye problems, small head size, or delayed development and/or intellectual disability.

Can I breastfeed while sick with chickenpox?

The chickenpox virus has not been found in breast milk of people with a chickenpox infection. Breast milk might contain antibodies that can help to protect your baby from getting chickenpox. However, because chickenpox is very contagious, talk to your child’s pediatrician right away if you come down with chickenpox. It is important to prevent your baby from coming into direct contact with the rash or the affected areas in order lower the chances of your baby from getting the virus. If you suspect your baby has any symptoms that could be due to chickenpox, contact your child’s healthcare provider.

What is the cause of chickenpox?

Chickenpox is caused by primary infection with the varicella-zoster virus (VZV), of the Herpesviridae family. The varicella-zoster virus (VZV) is sometimes called herpesvirus type 3. Humans are the only source of this disease. Chickenpox is highly contagious and the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) spreads very easily from person to person by breathing in airborne respiratory droplets from an infected person’s coughing or sneezing or through direct contact with the fluid from the open sores or fluid from shingles lesions. Chickenpox is acquired through contact with respiratory droplets or fluid from shingles lesions. A person who is not immune to the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) has a 70–80% chance of being infected with the virus if exposed to someone in the early stages of the disease.

The varicella-zoster virus (VZV) is a human alphaherpesvirus with worldwide distribution and is highly contagious 29. The varicella-zoster virus (VZV) is responsible for chickenpox (primary varicella infection) and herpes zoster or shingles infection (which is a reactivation of latent varicella infection).

Initially, viral replication occurs in the respiratory tract. The varicella-zoster virus (VZV) then invades local lymph nodes, leading to viremia and widespread dissemination. As the viremia increases, new skin vesicular lesions erupt, with individuals typically having 250 to 500 lesions in varying evolution stages 27.

The incubation period for varicella-zoster virus (VZV) is typically between 10 to 21 days. Individuals with primary varicella infection (chickenpox) may also experience a prodrome of fever, malaise, abdominal pain, and headaches. Patients with chickenpox are considered contagious from 1 to 2 days before developing the rash until all skin lesions have crusted over. Varicella infection in pregnant women can spread via the placenta and infect the fetus 20, 21.

After chickenpox (primary varicella infection), the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) becomes latent in the dorsal root ganglia (a collection of neuronal cell bodies of sensory neurons) 30. It can later reactivate as herpes zoster or shingles (reactivation of latent varicella infection). The specific mechanisms of varicella-zoster virus (VZV) reactivation are not fully understood 31. Scientists theorized that when the varicella-zoster virus (VZV)-specific immunity decreases, the latent virus in the ganglions reactivates, replicates, and then various herpes zoster (shingles) symptoms appear 32. Many factors affecting cellular immunity may cause the reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) 33. These risk factors for varicella-zoster virus (VZV) reactivation include old age, cellular immunodeficiency, genetic susceptibility, trauma, systemic diseases (such as diabetes, kidney disease, fever, hypertension, etc.), mental stress and fatigue 34, 35, 36.

The clinical manifestation of herpes zoster (shingles) includes a painful vesicular rash in a dermatomal distribution, followed by postherpetic neuralgia. Typically, a single dermatome is involved, although two or three adjacent dermatomes may be affected 37. The lesions usually do not cross the midline 37. Direct contact with the vesicles may be contagious, especially in non-immune or immunocompromised hosts. Herpes zoster (shingles) does not pose a risk to a developing fetus due to circulating protective maternal antibodies transmitted through placental transfer 28.

Chickenpox prevention

Chickenpox is highly preventable by vaccination with live attenuated varicella vaccine. Chickenpox vaccine became available in the United States in 1995. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends two doses of chickenpox (varicella) vaccine for children, adolescents, and adults who have never had chickenpox and were never vaccinated 38. Children are routinely recommended to receive the first dose at 12 through 15 months of age and the second dose at 4 through 6 years of age. During the first 25 years of the U.S. chickenpox vaccination program, the vaccine has prevented an estimated 91 million cases, 238,000 hospitalizations, and 2,000 deaths 39.

Chickenpox vaccination is especially important for:

- Healthcare professionals

- People who care for or are around other people whose body is less able to fight germs and sickness (weakened immune system)

- Teachers

- Childcare workers

- Residents and staff in nursing homes and other residential settings

- College students

- Inmates and staff of correctional institutions

- Military personnel

- Non-pregnant women of child-bearing age

- Premature infants born to susceptible mothers

- Infants born at less than 28 weeks gestation or who weigh ≤1000 grams, regardless of maternal immune status

- Immunocompromised people, including those who are undergoing immunosuppressive therapy, have malignant disease, or are immunodeficient

- Pregnant women

- Adolescents and adults living with children

- International travelers

Some people with a weakened immune system who do not have immunity against chickenpox may be considered for vaccination after talking with their doctor, including:

- People with HIV infection

- People with cancer, but whose disease is in remission

- People on low dose steroids

Two doses of varicella vaccine are recommended for all children, adolescents, and adults without evidence of immunity to varicella. Those who previously received one dose of varicella vaccine should receive their second dose for best protection against the disease.

Chickenpox vaccine

Two vaccines containing varicella virus are licensed for use in the United States 40.

- Varivax® is the single-antigen varicella vaccine 41.

- Contains only chickenpox vaccine.

- Is licensed for use in people 12 months of age or older.

- Can be given to children for their routine 2 doses of chickenpox vaccine at 12 through 15 months old and age 4 through 6 years old.

- ProQuad® is a combination measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella (MMRV) vaccine 42.

- Contains a combination of measles, mumps, rubella (German measles), and varicella (chickenpox) vaccines, which is also called MMRV.

- Is only licensed for use in children 12 months through 12 years of age.

Both vaccines contain live, attenuated varicella-zoster virus derived from the Oka strain.

Children 12 months through 12 years old

- 2 doses (0.5 ml each) of varicella vaccine should be given subcutaneously, separated by at least 3 months.

- Measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella (MMRV) vaccine is approved for healthy children in this age group.

Single-antigen vaccine and MMRV vaccine can be used for the routine 2-dose varicella vaccination.

- First dose: age 12 through 15 months

- Second dose: age 4 through 6 years

For the first dose, CDC recommends that MMR and varicella (MMRV) vaccines be given separately in children 12 through 47 months old unless the parent or caregiver expresses a preference for MMRV vaccine. For the second dose of measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella (MMRV) vaccines at any age (15 months–12 years) and for the first dose at age ≥48 months, use of MMRV vaccine generally is preferred over separate injections of MMR and varicella vaccines.

Both vaccines may be given at the same time as other vaccines for children age 12 through 15 months and age 4 through 6 years.

People 13 years or older

- 2 doses (0.5 ml each) of the single-antigen varicella vaccine subcutaneously 4 to 8 weeks apart

Measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella (MMRV) vaccine is NOT approved for people in this age group.

Post exposure chickenpox vaccination

Getting vaccinated after you are exposed to someone with chickenpox can:

- Prevent the disease or make it less serious.

- Protect you from chickenpox if you are exposed again in the future.

A healthcare provider can also prescribe a medicine to make chickenpox less severe if you:

- Are exposed to chickenpox.

- Do not have immunity against the disease.

- Are not eligible for vaccination.

What are the side effects of the chickenpox vaccine (varicella vaccine)?

Side effects of the chickenpox vaccine (varicella vaccine) include tenderness in the local area of the shot and occasionally a low-grade fever. A rash occurs in about 4 of 100 children who get the vaccine, generally around the area of the shot. A rash can also occur on parts of the body other than the area of the shot. There are usually fewer than 30 blisters that are a consequence of varicella vaccine. If someone develops blisters, they can, on rare occasions, infect someone who is susceptible (i.e., a person who has not previously been immunized against or infected with varicella virus). The blisters contain viruses that can spread to a susceptible person who comes into contact with them before they crust over. As such, if a vaccinated person develops a rash, susceptible people should not be exposed to the blisters.

Because the chickenpox vaccine contains gelatin, people who are severely allergic to gelatin cannot get the vaccine. Gelatin is also contained in foods, like Jell-O, so a child’s allergy may already be known before it is time to get the vaccine. People with severe allergic reactions to previous doses of varicella vaccine or to other ingredients in the vaccine should not get it.

People who are severely immune compromised, pregnant, or who have a parent or sibling with an inherited immune deficiency or one they were born with should not get chickenpox vaccine. In the latter situation, once chickenpox vaccine recipient is known to be immune competent, they can get vaccinated.

How effective is the varicella vaccine?

One dose varicella vaccine

- 1 dose of single-antigen varicella vaccine is:

- 82% effective at preventing any form of varicella

- Almost 100% effective against severe varicella

Two doses of varicella vaccine

- In a pre-licensure clinical trial, 2 doses of vaccine were:

- 98% effective at preventing any form of varicella

- 100% effective against severe varicella

- In post-licensure studies, two doses of vaccine were:

- 92% (range 88% to 98%) effective at preventing all varicella

In children with HIV-infection

- 1 dose of single-antigen varicella vaccine is:

- 82% effective at preventing any form of varicella

Who should NOT get chickenpox vaccine

You do not need to get the chickenpox vaccine if you have evidence of immunity against the disease.

Some people should NOT get chickenpox vaccine or they should wait.

- People should check with their doctor about whether they should get chickenpox vaccine if they:

- Have HIV and AIDS or another disease that affects the immune system.

- Are being treated with drugs that affect the immune system, such as steroids, for 2 weeks or longer.

- Have any kind of cancer.

- Are getting cancer treatment with radiation or drugs.

- Recently had a transfusion or were given other blood products.

- Are pregnant or may be pregnant.

Duration of chickenpox vaccine protection

It is not known how long a vaccinated person is protected against varicella. But, live vaccines in general provide long-lasting immunity.

- Several studies have shown that people vaccinated against varicella had antibodies for at least 10 to 20 years after vaccination. But, these studies were done before the vaccine was widely used and when infection with wild-type varicella was still very common.

- A case-control study conducted from 1997 to 2003 showed that 1 dose of varicella vaccine was 97% effective in the first year after vaccination and 86% effective in the second year. From the second to eighth year after vaccination, the vaccine effectiveness remained stable at 81 to 86%. Most vaccinated children who developed varicella during the 8 years after vaccination had mild disease 43.

- A clinical trial showed that children with 2 doses of varicella vaccine were protected 10 years after being vaccinated. Fewer people had breakthrough varicella after 2 doses compared with 1 dose. The risk of breakthrough varicella did not increase over time 44.

- A meta-analysis that included 1-dose vaccine effectiveness reported through 2015 found a pooled estimate of 82% within the first decade. Considering the age of participants in the studies and vaccine recommendations in each country, the median time since vaccination is likely lower than 10 years. Four studies reported decline in vaccine effectiveness with time since vaccination; however, the differences did not reach statistical significance 45.

- Two doses of varicella vaccine add improved protection, with a pooled estimate of 92% (assessed ~5 years after vaccination).

Varicella vaccine cost

Most health insurance plans cover the cost of vaccines. However, you may want to check with your insurance provider before going to the doctor. If you don’t have health insurance or if your insurance does not cover vaccines for your child, the Vaccines for Children Program (https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/vfc/index.html) may be able to help. This program helps families of eligible children who might not otherwise have access to vaccines. To find out if your child is eligible, visit the VFC website or ask your child’s doctor. You can also contact your state VFC coordinator here (https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/awardee-imz-websites.html).

Chickenpox vaccine near me

Vaccines may be available at private doctor offices, pharmacies, workplaces, community health clinics, health departments or other community locations, such as schools and religious centers. If your primary healthcare provider does not stock all the vaccines recommended for you, ask for a referral. Getting a vaccine at a doctor’s office or health department does not require a patient-specific prescription from another health care provider.

Many local pharmacies offer most recommended vaccines for adults, as well as some travel vaccines. If you plan on getting vaccinated at a pharmacy, consider calling the pharmacy ahead to find out if you need a prescription. The laws governing which vaccines a pharmacist can prescribe or administer vary by state. Some states allow pharmacists to independently administer vaccine without a patient-specific prescription from another health care provider and others do not. Laws governing patient-specific prescription can also vary by patient age or the vaccine needed.

You can also contact your state health department to learn more about where to get vaccines in your community.

My daughter had chickenpox at 10 months old, but now that she is 1 year old, her doctor said she should still get the chickenpox vaccine. Is this really necessary?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends vaccination of all children at 12 months of age who do not have evidence of immunity. Evidence of immunity can include:

- A diagnosis of chickenpox or shingles made by a doctor

- Laboratory confirmation of disease

- Laboratory evidence of immunity (blood test)

Because many rashes are misclassified, the CDC states that “if there is any doubt that the illness was actually varicella [chickenpox], the child should be vaccinated” 38, 46, 47

While you could get your daughter tested for evidence of antibodies to chickenpox, the test will require a blood draw and if it is negative, she will still need to get the vaccine. Furthermore, a dose of chickenpox vaccine even if she has had chickenpox will not hurt her; it will make her immunity stronger.

If we immunize children against chickenpox, will they be more likely to develop shingles later in life?

Shingles is a rash with extremely painful blisters that occur along a nerve, usually on the face, chest or abdomen. Shingles usually affects people 45 years old or older and occurs when the varicella virus reawakens (or reactivates). Although children usually completely recover from a chickenpox infection, the virus never really goes away. It lives silently in the nervous system and, when we get older, it can occasionally reawaken, causing shingles.

Like the natural virus, the varicella vaccine virus can also live silently in the nervous system. However, it has been shown that the varicella vaccine virus is much less likely to reawaken and, that when it reawakens, it is much less likely to cause severe shingles compared with natural varicella virus 48. This makes sense because the varicella vaccine virus is much, much weaker than the natural varicella virus.

The important question to ask yourself is: Would you rather have the more destructive, “wild type” varicella virus reawaken later in life, or the weakened varicella virus contained in the vaccine? Also, since the introduction of the varicella vaccine in 1996, the incidence of shingles in the United States has decreased.

If we immunize children with the varicella vaccine, won’t they be more likely to get chickenpox as adults?

Chickenpox is much more likely to cause severe disease in adults than in children. Adults are 10 times more likely to be hospitalized when they have chickenpox than are children. Therefore, one thing that you would never want the vaccine to do is shift the disease from childhood to adulthood. However, for a number of reasons, this is unlikely to happen:

- Several studies have shown that immunity to chickenpox lasts at least 20 years and is probably life-long.

- The varicella vaccine is made in a manner similar to the rubella vaccine. Experts immunize little girls with the rubella vaccine to protect them from catching rubella when they become pregnant as adults — an event that occurs 20, 30, or even 40 years later. And it works. The incidence of birth defects from rubella has decreased from as high as 20,000 cases per year to fewer than five cases per year.

- Measles vaccine, also made in a similar way, has been successfully used for more than 40 years without seeing a similar shift in age of disease.

Therefore, fading immunity, and a consequent shift of chickenpox infections from childhood to adulthood, is extremely unlikely to occur.

Should teenagers and adults get the varicella vaccine?

Any teenager or adult who has not had chickenpox or the chickenpox vaccine should receive chickenpox vaccine. Adults are 10 times more likely than children to be hospitalized with the severe consequences of chickenpox. These consequences include pneumonia and encephalitis (inflammation of the brain).

I got the chickenpox vaccine as an adult, but I got a fever and a rash, so should I get the second dose of chickenpox vaccine?

About 4 of every 100 adults who get chickenpox vaccine will develop a rash, usually with less than 10 blisters. You should still get your second dose of chickenpox vaccine in one to two months as recommended. Your reaction to the first dose indicates that your body has made an immune response to the chickenpox vaccine, so you are less likely to have the same thing happen after the second dose. However, the second dose will strengthen your immunity, so that if you are exposed to the chickenpox virus, you will be better protected.

Chickenpox signs and symptoms

In children, chickenpox usually begins as itchy small inflamed bumps (red papules) progressing to fluid filled blisters (vesicles) on the stomach, back and face, and then spreading to other parts of the body. Blisters can also arise inside the mouth. The itchy blister rash caused by chickenpox infection appears 7 to 21 days after exposure to the virus and usually lasts about five to 10 days.

Once the chickenpox rash appears, it goes through three phases:

- Raised pink or red bumps (papules), which break out over several days. About 24 to 36 hours after the first symptoms begin, a rash of small, flat, red spots appears. The spots usually begin on the trunk and face, later appearing on the arms and legs. Some people have only a few spots. Others have them almost everywhere, including on the scalp and inside the mouth.

- Small fluid-filled blisters (vesicles), which form in about one day and then break and leak. Within 6 to 8 hours, each spot becomes raised. It forms an itchy, round, fluid-filled blister against a red background and finally crusts. Spots continue to develop and crust for several days. A hallmark of chickenpox is that the rash develops in crops so that the spots are in various forms of development at any affected area. Very rarely, the spots become infected by bacteria, which can cause a severe skin infection (cellulitis or necrotizing fasciitis).

- Crusts and scabs, which cover the broken blisters and take several more days to heal. New spots usually stop appearing by the fifth day, the majority are crusted by the sixth day, and most disappear in fewer than 20 days.

New bumps continue to appear for several days, so you may have all three stages of the rash — bumps, blisters and scabbed lesions — at the same time. You can spread the virus to other people for up to 48 hours before the rash appears, and the virus remains contagious until all broken blisters have crusted over.

The rash spread pattern can vary from child to child. There may be only a scattering of vesicles, or the entire body may be covered with up to 500 vesicles. In severe cases, the rash can cover the entire body, and lesions may form in the throat, eyes, and mucous membranes of the urethra, anus and vagina. The vesicles tend to be very itchy and uncomfortable.

Some children may also experience additional symptoms such as high fever, headache, cold-like symptoms, loss of appetite, vomiting and diarrhea and tiredness and a general feeling of being unwell (malaise). Younger children often do not have these symptoms, but symptoms are often severe in adults.

Spots in the mouth quickly rupture and form raw sores (ulcers), which often make swallowing painful. Raw sores may also occur on the eyelids and in the upper airways, rectum, and vagina. The worst part of the illness usually lasts 4 to 7 days.

Chickenpox symptoms in adults

Chickenpox is usually more severe in adults and can be life-threatening in complicated cases. Most adults who get chickenpox experience prodromal symptoms for up to 48 hours before breaking out in the rash. These include fever, malaise, headache, loss of appetite and abdominal pain. Chickenpox is usually more severe in adults and can be life-threatening in complicated cases.

The blisters clear up within one to three weeks but may leave a few scars. These are most often depressed (anetoderma), but they may be thickened (hypertrophic scars). Scarring is prominent when the lesions get infected with bacteria.

Congenital varicella syndrome (fetal varicella syndrome)

Maternal chickenpox infection within the first 20 weeks of pregnancy can cause congenital varicella syndrome also called fetal varicella syndrome 49, 50, 51. Congenital varicella syndrome or fetal varicella syndrome affects <2% of babies born to mothers infected with chickenpox between 7 and 28 weeks of pregnancy, especially during 13 to 20 weeks 52. Congenital varicella syndrome is caused by the same varicella-zoster virus (VZV) as the chickenpox, a common childhood disease 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 21. The risk of a mother passing the varicella virus onto her baby is extremely low and affects 1% to 3% of fetuses 59, 60. Only a primary varicella infection can cause congenital varicella syndrome (fetal varicella syndrome) and most adults and children have already had chicken pox or have been vaccinated against it 61. Even if a mother does contract chicken pox while pregnant, there is only a 2 percent chance that the baby will develop congenital varicella syndrome 57, 62. The estimated prevalence of congenital varicella syndrome is one to five in 10,000 pregnancies, where primary infection in the first 20 weeks has been documented 60.

If you’re pregnant and haven’t ever had chicken pox, be very careful because varicella is highly contagious, there is a 90 percent chance that an infected person will spread chickenpox to a household member who has not had chicken pox before. A baby may contract a varicella infection in the uterus when the mother catches chicken pox and carries it through her bloodstream to the baby. The developing fetus is especially vulnerable to illness because its immune system is not yet strong enough to permanently fight off infection. Since a baby in utero cannot completely get rid of an infection, the varicella virus remains in the body, and can lead to congenital varicella syndrome, which may prevent the child’s vulnerable organs from developing correctly. The mechanism of congenital varicella syndrome (fetal varicella syndrome) is thought to be a consequence of the reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) in the uterus, akin to the mechanism of herpes zoster development, rather than being due to the primary chickenpox infection 63.

The infection rate of fetuses has been reported to range from 12%–30% 51. Congenital varicella syndrome (fetal varicella syndrome) has a 30% mortality and miscarriage rate of 3-8% 64. Only 1%–2% of cases of maternal chickenpox may result in congenital varicella syndrome, which is associated with severe, lifelong disabilities 56, 65.

According to literature, the most common clinical features of congenital varicella syndrome (fetal varicella syndrome) are 66, 67, 68 :

- Skin lesions that resemble scars, burns or present with hemangiomatous characteristics with a dermatomal distribution (72%);

- Central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) and peripheral nervous system abnormalities (62%) such as cortical atrophy, microcephaly, seizures and mental retardation;

- Eye abnormalities (52%) like chorioretinitis, cataract, Horner syndrome, and nystagmus;

- Limb hypoplasia (46%);

- Low birth weight (23%).

Babies born with congenital varicella syndrome may have may have some or all of the following symptoms 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78:

- Skin lesions that resemble scars, burns (mostly on arms and legs)

- thickened, overgrown scar tissue

- hardened, red and inflamed skin

- Central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) and peripheral nervous system abnormalities

- ventriculomegaly — enlarged ventricles of the brain

- hydrocephalus

- cortical atrophy — degeneration of outer portion of brain

- cerebellar atrophy

- microcephaly — abnormally small head

- intracranial calcifications

- facial nerve palsy,

- phrenic nerve palsy,

- recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy,

- bulbar palsy,

- brachial plexus palsy,

- autonomic nervous system dysfunction that controls involuntary functions e.g., Horner syndrome, neurogenic bladder, dysphagia, and anal sphincter dysfunction

- psychomotor skills — motor movements caused by mental process

- learning disabilities

- intellectual disabilities

- Eye abnormalities

- cataracts — clouding over the lens of the eye

- abnormally small eye(s) (microphthalmia)

- rapid, involuntary eye movement (nystagmus)

- chorioretinitis — inflammation of the choroids layer behind the retina

- optic nerve atrophy

- Limb hypoplasia — limb deficiencies, malformations and underdevelopment (e.g., talipes equinovarus or calcaneovalgus deformity, hypoplasia/atrophy of the limb, rudimentary digit, hypoplasia of ribs, and scoliosis)

- Gastrointestinal anomalies (e.g., duodenal stenosis, jejunoileal atresia, Meckel diverticulum, colonic atresia, colonic stricture, small left colon syndrome, and sigmoid atresia)

- Genitourinary anomalies (e.g., hydronephrosis, hydroureter, renal dysplasia, renal agenesis, and undescended testes)

- Low birth weight

You don’t have to worry about congenital varicella syndrome at all if you have already had chicken pox or been vaccinated against it. However, if you are pregnant and have not had chicken pox before, the following steps can help prevent congenital varicella syndrome:

- Avoid contact with anybody who has chicken pox. The greatest risk of developing congenital varicella syndrome is apparent when a nonimmune pregnant woman is infected during the 13th to 20th week of pregnancy 51.

- Susceptible people who are living with a pregnant woman should get the varicella vaccine.

- If you are already pregnant, do NOT get the varicella vaccine, as it contains a live version of the virus. Get vaccinated at least a month before your pregnancy or after giving birth.

- Evidence from prospective cohort studies suggests high rates of protection against fetal infection and congenital varicella syndrome in mothers with chicken pox who received varicella-zoster immune globulin (VZIG) (a specific immunoglobulin G antibody) 56, 51, 49.

If you contract chicken pox during your pregnancy, fetal ultrasounds can monitor your baby to determine if chicken pox affects your baby’s development.

If your baby is born with congenital varicella syndrome, doctors administer varicella-zoster immune globin (VZIG) against varicella-zoster virus, immediately after birth, in order to lessen the severity of the disease.

Figure 6. Congenital varicella syndrome baby with upper limb hypoplasia

Footnote: Linear, irregular, atrophic scar over the lateral aspect of the left lower half of arm, elbow and upper two thirds forearm associated with bridging erythematous cicatricial scar across elbow.

[Source 76 ]Chickenpox stages

Chickenpox happens in 3 stages. But new spots can appear while others are becoming blisters or forming a scab.

An itchy, spotty rash is the main symptom of chickenpox. It can be anywhere on the body. Once the chickenpox rash appears, it goes through three phases:

- Raised pink or red bumps (papules), which break out over several days. About 24 to 36 hours after the first symptoms begin, a rash of small, flat, red spots appears. The spots usually begin on the trunk and face, later appearing on the arms and legs. Some people have only a few spots. Others have them almost everywhere, including on the scalp and inside the mouth.

- Small fluid-filled blisters (vesicles), which form in about one day and then break and leak. Within 6 to 8 hours, each spot becomes raised. It forms an itchy, round, fluid-filled blister against a red background and finally crusts. Spots continue to develop and crust for several days. A hallmark of chickenpox is that the rash develops in crops so that the spots are in various forms of development at any affected area. Very rarely, the spots become infected by bacteria, which can cause a severe skin infection (cellulitis or necrotizing fasciitis).

- Crusts and scabs, which cover the broken blisters and take several more days to heal. New spots usually stop appearing by the fifth day, the majority are crusted by the sixth day, and most disappear in fewer than 20 days.

Stage 1 small spots appear

The pink or red spots (papules) can:

- be anywhere on the body, including inside the mouth and around the genitals, which can be painful

- spread or stay in a small area

- be red, pink, darker or the same colour as surrounding skin, depending on your skin tone

- be harder to see on brown and black skin

Figure 7. Chickenpox stage 1

Stage 2 small fluid-filled blisters (vesicles)

- The spots fill with fluid and become blisters. The blisters are very itchy and may burst.

- The blisters are pink and shiny. The skin around some spots appears slightly pink.

Figure 8. Chickenpox stage 2

Stage 3 crusts and scabs

- The spots form a scab. Some scabs are flaky while others leak fluid.

- Most of the spots have scabs over them. The scabs are pink, purple or grey. There are also a few spots without scabs, which look like small blisters. These are slightly darker in colour than the surrounding skin.

Figure 9. Chickenpox stage 3

Complications of chickenpox

In healthy children, chickenpox infection is usually an uncomplicated, self-limiting disease. Risk of complications from chickenpox is increased for newborns, adults, and people who have a weakened immune system or certain disorders.

Pregnant women who get varicella are at risk of serious complications, such as pneumonia, and may die as a result. Chickenpox can also be transmitted to the fetus, especially if chickenpox develops during the 1st or early 2nd trimester. Such an infection can result in scars on the skin, birth defects, and a low birth weight.

Chickenpox complications may include:

- Secondary bacterial infection of skin lesions caused by scratching

- Infection may lead to abscess, cellulitis, necrotizing fasciitis and gangrene

- Dehydration from vomiting and diarrhea

- Worsening of asthma

- Viral pneumonia. Lung infection (pneumonia) occurs in about 1 out of 400 adults, resulting in cough and difficulty breathing. Pneumonia rarely develops in young children who have a normal immune system.

- Chickenpox lesions may heal with scarring.

Some complications are more commonly seen in immunocompromised and adult patients with chickenpox:

- Disseminated primary varicella infection; this carries high morbidity

- Central nervous system complications such as Reye syndrome, Guillain-Barré syndrome and encephalitis

- Brain infection (encephalitis) is less common and causes unsteadiness in walking, headache, dizziness, confusion, and seizures. In adults, encephalitis can be life threatening. It occurs in 1 to 2 of 1,000 cases of chickenpox.

- Reye syndrome is a rare but very severe complication that occurs almost only in those younger than 18 following the use of aspirin. Therefore, aspirin should not be given to children with chickenpox. Reye syndrome may begin 3 to 8 days after the rash begins.

- Thrombocytopenia and purpura.

- Inflammation of the liver (hepatitis) and bleeding problems may also occur.

Shingles (herpes zoster)

- The varicella-zoster virus (VZV) remains dormant in sensory ganglia after infection.

- It may reactivate after many years as shingles. Shingles presents with grouped vesicular lesions, which usually affect a single dermatome.

- Other infections occurring as a result of reactivation of virus include post-herpetic neuralgia, vasculopathy (any disease affecting the blood vessels), myelopathy (injury to the spinal cord), acute retinal necrosis (inflammatory condition of the retina), meningitis or meningoencephalitis, cerebellitis and zoster sine herpete (pain without rash) 79, 80, 81, 82, 83. Among them, varicella-zoster virus (VZV) cerebrovasculopathy is caused by viral infection of the arteries, leading to pathological vascular remodeling and an ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, with a mortality rate of 25%, and one-third of patients with virology-proven varicella-zoster virus (VZV) vascular disease had no previous rash 84. In addition, by reactivating and infecting the meninges, brain parenchyma, and nerve roots, the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) can cause varicella-zoster meningitis, varicella-zoster encephalitis, and varicella-zoster radiculitis 85. Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) meningoencephalitis can manifest as mild aseptic meningitis but also as severe encephalitis with edema, brain necrosis, and demyelination 81. The mortality rate of varicella-zoster virus (VZV) encephalitis is as high as 9% 86. Besides, varicella-zoster virus (VZV) meningoradiculitis can be lethal as reported 87. Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) myelopathy can present as a fatal myelitis, mostly in immunocompromised individuals. Postmortem analyses of the spinal cord from fatal cases have revealed a apparent invasion of the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) in the parenchyma with associated inflammation and, in some instances, spread of the virus to adjacent nerve roots 88.

- Evidence suggests that persistent radicular pain from herpes zoster can be caused by chronic activation of the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) and ganglionitis. In a patient who had experienced chronic trigeminal neuralgia for more than 1 year, the trigeminal ganglionic mass was removed and the pathological and virological analyses discovered active varicella-zoster virus (VZV) ganglionitis 89. In another study, active varicella-zoster virus (VZV) ganglionitis was found in the trigeminal ganglia of a patient who experienced chronic trigeminal neuralgia for months before death 90. Using human dorsal root ganglia xenografts in immunodeficient mice, Zerboni and Arvin 91 demonstrated varicella-zoster virus (VZV) replication in mechanoreceptive neurons; They also found that the VZV in the dorsal root ganglia triggers release of pro-inflammatory cytokines that cause neuronal damage. These findings may help to explain the neurologic sequelae in herpes zoster, zoster sine herpete (pain without rash) and post-herpetic neuralgia patients.

Chickenpox diagnosis

Diagnosis of chickenpox is usually made on the presence of its characteristic rash and the presence of different stages of lesions simultaneously. A clue to the diagnosis is in knowing that the patient has been exposed to an infected contact within the 10–21 day incubation period. Patients may also have prodromal signs and symptoms.

If there’s any doubt about the diagnosis, chickenpox can be confirmed with lab tests, including blood tests or a culture of lesion samples.

Laboratory tests are often undertaken to confirm the diagnosis:

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) detects the varicella virus in skin lesions and is the most accurate method for diagnosis.

- The culture of blister fluid is time-consuming and is less frequently performed.

- Serology (IgM and IgG) is most useful in pregnant women, or before prescribing immune suppression medication to determine the need for pre-treatment immunization.

Figure 10. Varicella recommended testing

[Source 92 ]Figure 11. Varicella tests

[Source 92 ]Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is the most useful laboratory test for confirming suspected varicella (chickenpox) and shingles (herpes zoster). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) can detect varicella-zoster virus (VZV) DNA rapidly and sensitively in skin lesions (vesicles, scabs, maculopapular lesions).

Specimens for PCR testing 93:

- Vesicular lesions or scabs, if present, are the best for sampling.

- Adequate collection of specimens from maculopapular lesions in vaccinated people can be a challenge. However, one study 94 that compares a variety of specimens from the same patients vaccinated with one dose of varicella vaccine (chickenpox vaccine) suggests that maculopapular lesions collected with proper technique are a highly reliable specimen types for the detection of varicella-zoster virus (VZV).

- Other sources, such as nasopharyngeal secretions, saliva, urine, bronchial washings, and cerebrospinal fluid are less likely to provide an adequate sample; they often lead to false negative results.

Other viral isolation techniques for the confirmation of varicella are direct fluorescent antibody assay (DFA) and viral culture 93. However, these techniques are generally not recommended because they are less sensitive than polymerase chain reaction (PCR) 93. In the case of viral culture, these techniques take longer to generate results.

Like direct fluorescent antibody assay (DFA), a Tzanck smear has a rapid turnaround time but is not recommended because of its limited sensitivity and is not specific for varicella-zoster virus 93. Moreover, real-time PCR (RT-PCR) protocols can be completed within one day.

Serologic tests

Serologic methods have limited use for laboratory confirmation of herpes zoster and should only be used when suitable specimens for PCR testing are not available 93.

IgM serologic testing is considerably less sensitive than PCR testing of skin lesions. IgM serology provides evidence for a recent active varicella-zoster virus infection. However, it cannot distinguish between primary infection and reinfection or reactivation from latent varicella-zoster virus (VZV) 93. This is because specific IgM antibodies are produced with each exposure to varicella-zoster virus (VZV). IgM tests are also inherently prone to poor specificity 93.

Specimens for serologic testing

Measuring acute and convalescent sera also has limited value, since it is difficult to detect an increase in IgG for laboratory diagnosis of herpes zoster 93.

Paired acute and convalescent sera showing a four-fold rise in IgG antibodies have excellent specificity for varicella 93. However, they are not as sensitive as PCR of skin lesions for the diagnosis of varicella 93. People with a prior history of varicella vaccination or disease may have very high baseline titers and may not achieve a four-fold increase in the convalescent sera 93. The usefulness of this method for diagnosing varicella is further limited as it requires two office visits. A single positive IgG ELISA result cannot confirm a varicella case 93.

Chickenpox treatment

For most healthy patients with chickenpox, symptomatic therapy is usually all that is required.

- Trim children’s fingernails to minimize scratching.

- Take a warm bath and apply moisturizing cream.

- Acetaminophen (paracetamol) can reduce fever and pain

- Avoid non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others) use outside of hospital settings due to the increased risk of severe cutaneous complications such as invasive group A streptococcal superinfections.

- Do not use aspirin in children as this is associated with Reye syndrome.

- Calamine lotion and oral antihistamines may relieve itching.

- Consider oral aciclovir (antiviral agent) in people older than 12 years, which reduces the number of days with a fever.

Immunocompromised patients with chickenpox need intravenous treatment with the antiviral aciclovir.

In cases of unintentional exposure to the varicella-zoster virus (VZV), varicella-zoster immune globulin if given within 96 hours of initial contact can reduce the severity of the disease though not prevent it. This is used where there is no previous history of chickenpox (or the patient has no antibodies to the varicella-zoster virus on blood testing) in pregnancy, in the first 28 days after delivery, and in immune deficient or immune-suppressed patients.

Varicella-zoster immune globulin

For people exposed to varicella or herpes zoster who cannot receive varicella vaccine, varicella-zoster immune globulin can prevent varicella from developing or lessen the severity of the disease 95. Varicella-zoster immune globulin is recommended for people who cannot receive the vaccine and 1) who lack evidence of immunity to varicella, 2) whose exposure is likely to result in infection, and 3) are at high risk for severe varicella 95.

The varicella-zoster immune globulin product licensed for use in the United States is VariZIG. Varicella-zoster immune globulin (VariZIG) should be given as soon as possible after exposure to varicella-zoster virus (VZV); it can be given within 10 days of exposure. VariZIG is commercially available from a broad network of specialty distributors in the United States (list available at https://varizig.com).

Timing of varicella-zoster immune globulin (VariZIG) administration. CDC recommends administration of VariZIG as soon as possible after exposure to varicella-zoster virus and within 10 days 96.

Patient groups for whom varicella-zoster immune globulin (VariZIG) is recommended. Patients without evidence of immunity to varicella who are at high risk for severe varicella and complications, who have been exposed to varicella or herpes zoster, and for whom varicella vaccine is contraindicated, should receive varicella-zoster immune globulin (VariZIG). Patient groups recommended by CDC to receive VariZIG include the following 96, 97:

- Immunocompromised patients without evidence of immunity.

- Newborn infants whose mothers have signs and symptoms of varicella around the time of delivery (i.e., 5 days before to 2 days after).

- Hospitalized premature infants born at ≥28 weeks of gestation whose mothers do not have evidence of immunity to varicella.

- Hospitalized premature infants born at <28 weeks of gestation or who weigh ≤1,000 g at birth, regardless of their mothers’ evidence of immunity to varicella.

- Pregnant women without evidence of immunity.

Varicella-zoster immune globulin administration

Varicella-zoster immune globulin (VariZIG) is supplied in 125-IU vials and should be administered intramuscularly as directed by the manufacturer. The recommended dose is 125 IU/10 kg of body weight, up to a maximum of 625 IU (five vials). The minimum dose is 62.5 IU (0.5 vial) for patients weighing ≤2.0 kg and 125 IU (one vial) for patients weighing 2.1–10.0 kg 98.

Unchanged from previous recommendations 97, for patients who become eligible for vaccination, varicella vaccine should be administered ≥5 months after VariZIG administration. Because varicella zoster immune globulin might prolong the incubation period by ≥1 week, any patient who receives VariZIG should be observed closely for signs and symptoms of varicella for 28 days after exposure. Antiviral therapy should be instituted immediately if signs or symptoms of varicella occur. Most common adverse reactions following VariZIG administration were pain at injection site (2%) and headache (2%) 98.

Contraindications for varicella-zoster immune globulin (VariZIG) administration include a history of anaphylactic or severe systemic reactions to human immune globulins and IgA-deficient patients with antibodies against IgA and a history of hypersensitivity 98.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends that certain groups at increased risk for moderate to severe varicella be considered for oral acyclovir or valacyclovir treatment. These high risk groups include:

- Healthy people older than 12 years of age

- People with chronic skin disorders such as eczema or pulmonary disorders

- People receiving long-term salicylate therapy

- People receiving short, intermittent, or aerosolized courses of corticosteroids

Some healthcare providers may elect to use oral acyclovir or valacyclovir for secondary cases within a household. For maximum benefit, oral acyclovir or valacyclovir therapy should be given within the first 24 hours after the varicella rash starts.

Oral acyclovir or valacyclovir therapy is not recommended by American Academy of Pediatrics for use in otherwise healthy children experiencing typical varicella without complications. Acyclovir is a category B drug based on the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Drug Risk Classification in pregnancy. Some experts recommend oral acyclovir or valacyclovir for pregnant women with varicella, especially during the second and third trimesters. Intravenous acyclovir is recommended for the pregnant patient with serious, viral-mediated complications of varicella, such as pneumonia.

Intravenous acyclovir therapy is recommended for severe disease (e.g., disseminated varicella-zoster virus (VZV) such as pneumonia, encephalitis, thrombocytopenia, severe hepatitis) and for varicella in immunocompromised patients (including patients being treated with high-dose corticosteroid therapy for >14 days).

Famciclovir is available for treatment of varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infections in adults, but its efficacy and safety have not been established for children. In cases of infections caused by acyclovir-resistant varicella-zoster virus (VZV) strains, which usually occur in immunocompromised people, Foscarnet should be used to treat the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infection, but consultation with an infectious disease specialist is recommended.

Chickenpox treatment at home

To help ease the symptoms of an uncomplicated case of chickenpox, follow these self-care measures.

Avoid scratching

Scratching can cause scarring, slow healing and increase the risk that the sores will become infected. If your child can’t stop scratching:

- Put gloves on his or her hands, especially at night

- Trim his or her fingernails

Relieve the itch and other symptoms

The chickenpox rash can be very itchy, and broken vesicles sometimes sting. These discomforts, along with fever, headache and fatigue, can make anyone miserable. For relief, try:

- A cool bath with added baking soda, aluminum acetate (Domeboro, others), uncooked oatmeal or colloidal oatmeal — a finely ground oatmeal that is made for soaking.

- Calamine lotion dabbed on the spots.

- A soft, bland diet if chickenpox sores develop in the mouth.

- Antihistamines such as diphenhydramine (Benadryl, others) for itching. Check with your doctor to make sure your child can safely take antihistamines.

- Acetaminophen (Tylenol, others) for a mild fever.

If fever lasts longer than four days and is higher than 102, call your doctor. And don’t give aspirin to children and teenagers who have chickenpox because it can lead to a serious condition called Reye’s syndrome.

Chickenpox prognosis

Healthy children nearly always recover from chickenpox without problems. Before routine immunization, about 4 million people developed chickenpox annually in the United States, and about 100 to 150 of them died each year because of complications of chickenpox 99.

In adults, chickenpox is more severe, and the risk of dying is higher.

Chickenpox is particularly severe in people with a weakened immune system.

When people who have been vaccinated develop chickenpox, the disease is less severe, and fewer of these people die.

- Chickenpox/Varicella Vaccination. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/varicella/index.html[↩]

- Gershon A.A., Breuer J., Cohen J.I., Cohrs R.J., Gershon M.D., Gilden D., Grose C., Hambleton S., Kennedy P.G.E., Oxman M.N., et al. Varicella zoster virus infection. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2015;1:15016. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.16[↩]

- Bernal JL, Hobbelen P, Amirthalingam G. Burden of varicella complications in secondary care, England, 2004 to 2017. Euro Surveill. 2019 Oct;24(42):1900233. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2019.24.42.1900233[↩]

- Yokota K, Tamiya A, Sahara T, Nakamura-Uchiyama F. Adult Chickenpox. Intern Med. 2020 Aug 1;59(15):1923. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.4478-20[↩][↩]

- Sun, J., Liu, C., Peng, R. et al. Cryo-EM structure of the varicella-zoster virus A-capsid. Nat Commun 11, 4795 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18537-y[↩]

- Gnann JW Jr, Whitley RJ. Clinical practice. Herpes zoster. N Engl J Med. 2002 Aug 1;347(5):340-6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp013211[↩][↩]

- Heininger U, Seward JF. Varicella. Lancet. 2006 Oct 14;368(9544):1365-76. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69561-5. Erratum in: Lancet. 2007 Feb 17;369(9561):558[↩]

- Pergam SA, Limaye AP; AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Varicella zoster virus (VZV) in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2009 Dec;9 Suppl 4(Suppl 4):S108-15. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02901.x[↩]

- Rosamilia, L.L. Herpes Zoster Presentation, Management, and Prevention: A Modern Case-Based Review. Am J Clin Dermatol 21, 97–107 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40257-019-00483-1[↩]

- Cohen JI. Clinical practice: Herpes zoster. N Engl J Med. 2013 Jul 18;369(3):255-63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1302674[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Yamaoka-Tojo M, Tojo T. Herpes Zoster and Cardiovascular Disease: Exploring Associations and Preventive Measures through Vaccination. Vaccines (Basel). 2024 Feb 28;12(3):252. doi: 10.3390/vaccines12030252[↩]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Varicella-related deaths among adults–United States, 1997. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1997 May 16;46(19):409-12. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00047618.htm[↩]

- Gilden DH, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, LaGuardia JJ, Mahalingam R, Cohrs RJ. Neurologic complications of the reactivation of varicella-zoster virus. N Engl J Med. 2000 Mar 2;342(9):635-45. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003023420906. Erratum in: N Engl J Med 2000 Apr 6;342(14):1063.[↩][↩]

- Kawai K, Gebremeskel BG, Acosta CJ. Systematic review of incidence and complications of herpes zoster: towards a global perspective. BMJ Open. 2014 Jun 10;4(6):e004833. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-004833[↩]

- Dworkin RH, Johnson RW, Breuer J, et al. Recommendations for the management of herpes zoster. Clin Infect Dis. 2007 Jan 1;44 Suppl 1:S1-26. doi: 10.1086/510206[↩][↩]

- Yawn BP, Itzler RF, Wollan PC, Pellissier JM, Sy LS, Saddier P. Health care utilization and cost burden of herpes zoster in a community population. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009 Sep;84(9):787-94. doi: 10.4065/84.9.787. Erratum in: Mayo Clin Proc. 2010 Jan;85(1):102.[↩]

- Lin Y.H., Huang L.M., Chang I.S., Tsai F.Y., Lu C.Y., Shao P.L., Chang L.Y., Varicella-Zoster Working Group, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, Taiwan Disease burden and epidemiology of herpes zoster in pre-vaccine Taiwan. Vaccine. 2010;28:1217–1220. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.11.029[↩][↩]

- Yawn BP, Saddier P, Wollan PC, St Sauver JL, Kurland MJ, Sy LS. A population-based study of the incidence and complication rates of herpes zoster before zoster vaccine introduction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007 Nov;82(11):1341-9. doi: 10.4065/82.11.1341. Erratum in: Mayo Clin Proc. 2008 Feb;83(2):255.[↩][↩]

- Le P, Rothberg M. Herpes zoster infection. BMJ. 2019 Jan 10;364:k5095 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k5095[↩]

- Cobelli Kett J. Perinatal varicella. Pediatr Rev. 2013 Jan;34(1):49-51. doi: 10.1542/pir.34-1-49[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Smith CK, Arvin AM. Varicella in the fetus and newborn. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009 Aug;14(4):209-17. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2008.11.008[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Patil A, Goldust M, Wollina U. Herpes zoster: A Review of Clinical Manifestations and Management. Viruses. 2022 Jan 19;14(2):192. doi: 10.3390/v14020192[↩]

- Moffat J, Ku CC, Zerboni L, et al. VZV: pathogenesis and the disease consequences of primary infection. In: Arvin A, Campadelli-Fiume G, Mocarski E, et al., editors. Human Herpesviruses: Biology, Therapy, and Immunoprophylaxis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2007. Chapter 37. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK47382[↩]

- de Oliveira Gomes J, Gagliardi AM, Andriolo BN, Torloni MR, Andriolo RB, Puga MEDS, Canteiro Cruz E. Vaccines for preventing herpes zoster in older adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023 Oct 2;10(10):CD008858. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008858.pub5[↩]

- Mother To Baby | Fact Sheets [Internet]. Brentwood (TN): Organization of Teratology Information Specialists (OTIS); 1994-. Varicella Infection (Chickenpox) 2021 Apr. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK583011[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Miller E, Cradock-Watson JE, Ridehalgh MK. Outcome in newborn babies given anti-varicella-zoster immunoglobulin after perinatal maternal infection with varicella-zoster virus. Lancet. 1989 Aug 12;2(8659):371-3. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90547-3[↩][↩]