Contents

- What is ovarian cancer

- Female reproductive system

- Ovarian cancer types

- Ovarian cancer signs and symptoms

- Can ovarian cancer be found early?

- Ovarian cancer causes

- Ovarian cancer risk factors

- Getting older

- Being overweight or obese

- Having children later or never having a full-term pregnancy

- Using fertility treatment

- Taking hormone therapy after menopause

- Having a family history of ovarian cancer, breast cancer, or colorectal cancer

- Having a family cancer syndrome

- Having had breast cancer

- Endometriosis or diabetes

- Smoking and alcohol use

- Asbestos

- Factors with unclear effects on ovarian cancer risk

- Factors that can lower risk of ovarian cancer

- Ovarian cancer prevention

- Ovarian cancer diagnosis

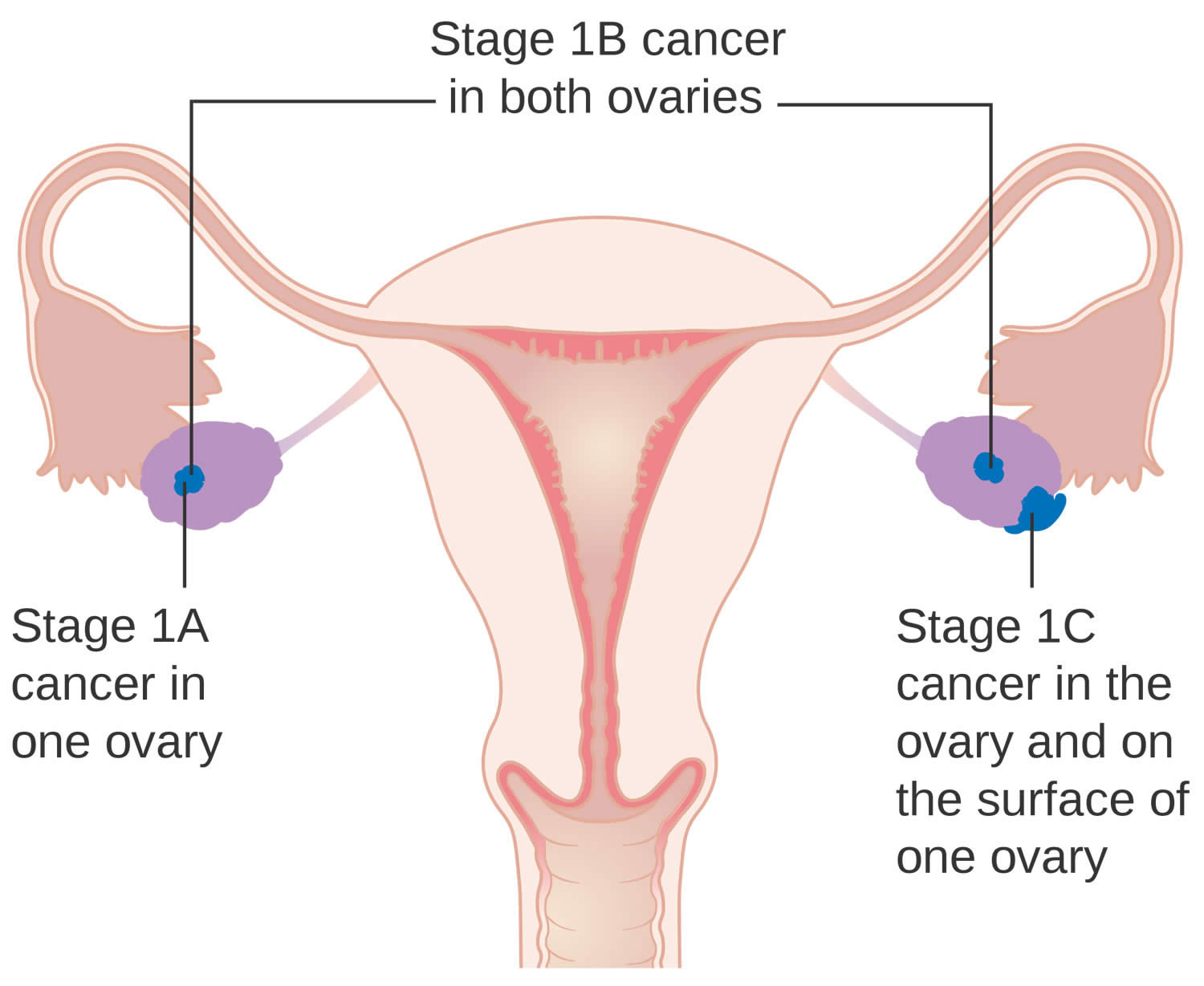

- Ovarian cancer stages

- Ovarian cancer treatment

- Surgery

- Chemotherapy

- Targeted Drug Therapy for Ovarian Cancer

- Radiotherapy

- Hormone therapy

- Immunotherapy

- Supportive (palliative) care

- Ovarian cancer treatment and fertility

- Stage 1 ovarian cancer treatment

- Stage 2 ovarian cancer treatment

- Stage 3 ovarian cancer treatment

- Stage 4 ovarian cancer treatment

- Coping and support

- Ovarian cancer prognosis

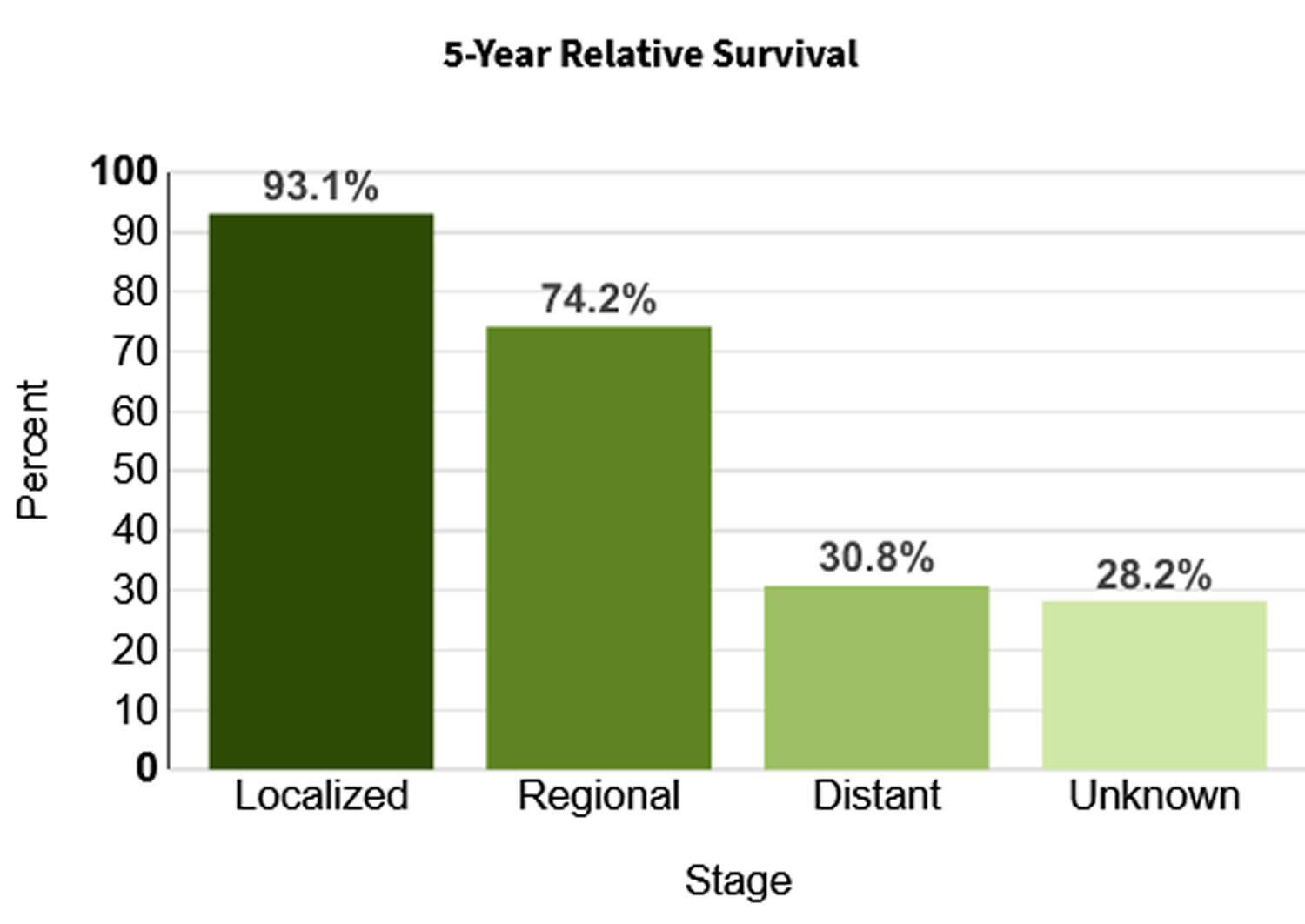

- Ovarian cancer survival rate

What is ovarian cancer

Ovarian cancer is cancer that forms in tissues of the ovary (one of a pair of female reproductive glands in which the eggs or ova, are formed). The ovaries are a pair of small organs in the female reproductive system that contain and release an egg once a month in women of menstruating age. This is known as ovulation. Ovarian cancers were previously believed to begin only in the ovaries, but recent evidence suggests that many ovarian cancers may actually start in the cells in the far (distal) end of the fallopian tubes.

Most ovarian cancers are either ovarian epithelial cancers (cancer that begins in the cells on the surface of the ovary) or malignant germ cell tumors (cancer that begins in egg cells). Fallopian tube cancer and primary peritoneal cancer are similar to ovarian epithelial cancer and are staged and treated the same way.

In general, cancer begins when a cell develops errors (mutations) in its DNA. The mutations tell the cell to grow and multiply quickly, creating a mass (tumor) of abnormal cells. The abnormal cells continue living when healthy cells would die. They can invade nearby tissues and break off from an initial tumor to spread elsewhere in the body (metastasize).

There are several types of ovarian cancer. They include:

- Epithelial ovarian cancer, which affects the outer surface layers of the ovary; it is by far the most common type. About 90 percent of ovarian cancers are epithelial tumors.

- Germ cell ovarian cancer, which originate in the cells that make the eggs. These rare ovarian cancers tend to occur in younger women.

- Stromal tumors, which develop within the cells that release female hormones. Stromal tumors are usually diagnosed at an earlier stage than other ovarian cancers. About 7 percent of ovarian tumors are stromal.

It is also possible to have borderline epithelial tumors which are not as aggressive as other epithelial tumors. These are sometimes called ‘low malignant potential’ or LMP tumors.

Ovarian cancer mainly develops in older women who have experienced menopause (usually over the age of 50), but it can affect women of any age. About half of the women who are diagnosed with ovarian cancer are 63 years or older. It is more common in white women than African-American women 1.

Ovarian cancer can spread to other parts of the reproductive system and the surrounding areas, including the womb (uterus), vagina and abdomen.

The symptoms of ovarian cancer can be difficult to recognize, particularly in the early stages of the disease. They are often the same as the symptoms of other, less serious, conditions, such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or premenstrual syndrome (PMS). The symptoms of ovarian cancer can be similar to other conditions making them difficult to recognize. However, there are early symptoms to look out for such as pain in the pelvis and lower stomach, persistent bloating and difficulty eating. Consult your doctor if you are experiencing any of these symptoms.

The most common symptoms of ovarian cancer are:

- Pain. You might have pain or discomfort in:

- your belly (abdomen)

- the area between your hip bones (pelvis)

- your back – although this is less common

- Swollen belly. Feeling bloated or an increase in the size of your abdomen that doesn’t go away can be a symptom of ovarian cancer.

- Loss of appetite. You might feel full quickly when you eat. Or you may not feel like eating.

- Urinary changes. You may need to pee more often, or have to go more urgently.

You may also have some other symptoms including:

- Tiredness. You might feel extremely tired for no obvious reason if you have ovarian cancer.

- Bowel changes. You might have loose poop or need to poop more often (diarrhea). Or you may go less often or have hard poop (constipation).

- Weight loss and feeling sick. You might lose weight even if you aren’t trying to. This might be due to feeling sick.

- Indigestion. Indigestion causes heartburn, bloating and sickness. It is a common problem in the general population, and for most people it isn’t a sign of cancer.

- Vaginal bleeding. You might notice bleeding in between your periods. Or you could have bleeding from your vagina after your menopause.

Ovarian cancer often goes undetected until it has spread within the pelvis and abdomen. At this late stage, ovarian cancer is more difficult to treat and is frequently fatal. Early-stage ovarian cancer, in which the disease is confined to the ovary, is more likely to be treated successfully.

Surgery and chemotherapy are generally used to treat ovarian cancer. The amount and type of surgery you have depends on how far your cancer has spread and on your general health. For women of childbearing age who have certain kinds of tumors and whose cancer is in the earliest stage, it may be possible to treat the disease without removing both ovaries and the uterus.

Some women with ovarian cancer might have:

- Targeted cancer drugs

- Hormone therapy

- Radiotherapy (radiation therapy)

The American Cancer Society estimates for ovarian cancer in the United States for 2025 are 1, 2:

- New cases: About 20,890 women will receive a new diagnosis of ovarian cancer. The rate at which women are diagnosed with ovarian cancer has been slowly falling over the past 20 years. The incidence rate declined by 1% to 2% per year from 1990 to the mid-2010s and by almost 2% per year from 2012 to 2021. This trend is likely due at least in part to increased oral contraceptive use in the latter half of the past century and decreased menopausal hormone therapy use during the 2000s, both of which can lower risk.

- Deaths: About 12,730 women will die from ovarian cancer. Ovarian cancer ranks fifth in cancer deaths among women, accounting for more deaths than any other cancer of the female reproductive system. Ovarian cancer mortality has declined from 2% annually during the 2000s and early 2010s to more than 3% annually from 2016 to 2020, reflecting both decreased incidence and improved treatment.

- 5-Year Relative Survival: 50.9%. Relative survival is an estimate of the percentage of patients who would be expected to survive the effects of their cancer. It excludes the risk of dying from other causes. Because survival statistics are based on large groups of people, they cannot be used to predict exactly what will happen to an individual patient. No two patients are entirely alike, and treatment and responses to treatment can vary greatly.

- Ovarian cancer deaths as a percentage of All Cancer Deaths: 2.1%.

- Rate of New Cases and Deaths per 100,000: The rate of new cases of ovarian cancer was 10.2 per 100,000 women per year. The death rate was 6.0 per 100,000 women per year. These rates are age-adjusted and based on 2017–2021 cases and 2018–2022 deaths.

- Lifetime Risk of Developing Ovarian Cancer: Approximately 1.1 percent of women will be diagnosed with ovarian cancer at some point during their lifetime, based on 2018–2021 data.

- In 2021, there were an estimated 238,484 women living with ovarian cancer in the United States.

A woman’s risk of getting ovarian cancer during her lifetime is about 1 in 91. Her lifetime chance of dying from ovarian cancer is about 1 in 143. These statistics don’t count low malignant potential ovarian tumors.

Known risk factors for ovarian cancer include:

- Getting older: women who are over 50 are more likely to develop ovarian cancer than younger women. The risk of ovarian cancer increases steeply from around 45 years. And is greatest in those aged between 75 and 79 years.

- Inheriting a faulty gene called a gene mutation that increases the risk of ovarian cancer. Between 5 and 15 out of 100 ovarian cancers (5 to 15%) are caused by an inherited faulty gene. Mutations in the breast cancer susceptibility genes 1 and 2 (BRCA1 and BRCA2), and those associated with Lynch syndrome, raise ovarian cancer risk.

- Having a strong family history of ovarian cancer, breast cancer, or some other cancers, including colorectal cancer and endometrial cancer

- Having had breast cancer in the past. The risk is higher in women diagnosed with breast cancer at a younger age. And those with estrogen receptor negative (ER negative) breast cancer.

Only around 5-15% of all ovarian cancers are due to inherited factors.

Research suggests that the risk of ovarian cancer is slightly higher for women who:

- have medical conditions such as endometriosis and diabetes. Studies have shown that women with endometriosis or diabetes have an increased risk of ovarian cancer. In diabetics, the increase in risk might be higher in those that use insulin.

- use long-term hormone replacement therapy (HRT). Using HRT (hormone replacement therapy) after the menopause increases the risk of ovarian cancer.

- had early puberty (menstruating before 12) or late menopause (onset after 50)

- smoke cigarettes. Smoking can increase your risk of certain types of ovarian cancer such as mucinous ovarian cancer. The longer you have smoked, the greater the risk.

- are overweight or obese. Having excess body fat is linked to an increase in risk of ovarian cancer.

Women have a lower risk of developing ovarian cancer if:

- they had a baby before the age of 26

- they used oral contraceptives (the pill) for at least 3 months

- they have had a hysterectomy (removal of the uterus) and tubal ligation (tubes tied)

Make an appointment with your doctor if you have any signs or symptoms that worry you.

If you have a family history of ovarian cancer or breast cancer, talk to your doctor about your risk of ovarian cancer. Your doctor may refer you to a genetic counselor to discuss testing for certain gene mutations that increase your risk of breast and ovarian cancers.

Female reproductive system

The female reproductive system includes parts of the female body that are involved in sexual activity, fertility, pregnancy and childbirth. The female reproductive system is made up of female body parts that include the following:

- Ovaries — There are 2 ovaries, which are about the size and shape of almonds, 1 ovary on each side of the uterus where female hormones (estrogen and progesterone) are produced, and eggs (ova) are stored to mature. Every month, an egg (ovum) is released. This is called ovulation. All the other female reproductive organs are there to transport, nurture and otherwise meet the needs of the egg or developing fetus.

- Fallopian tubes are 2 thin tubes that connect your ovaries to your uterus (womb), allowing the egg (ovum) to travel to your uterus (womb).

- The fallopian tubes are about 10 cm long and begin as funnel-shaped passages next to the ovary. They have a number of finger-like projections known as fimbriae on the end near the ovary. When an egg is released by the ovary it is ‘caught’ by one of the fimbriae and transported along the fallopian tube to the uterus. The egg is moved along the fallopian tube by the wafting action of cilia — hairy projections on the surfaces of cells at the entrance of the fallopian tube — and the contractions made by the tube. It takes the egg about 5 days to reach the uterus and it is on this journey down the fallopian tube that fertilisation may occur if a sperm penetrates and fuses with the egg. The egg, however, is usually viable for only 24 hours after ovulation, so fertilization usually occurs in the top one-third of the fallopian tube.

- Uterus (the womb) — Your uterus also known as the womb is a hollow muscular organ about the size of a pear (in women who have never been pregnant) that exists to house a developing fertilized egg (zygote). The main part of the uterus which sits in the pelvic cavity is called the body of the uterus, while the rounded region above the entrance of the fallopian tubes is the fundus and its narrow outlet, which protrudes into the vagina, is the cervix. The thick wall of your uterus is composed of 3 layers. The inner layer is known as the endometrium. The inner lining of your uterus (endometrium) thickens with blood and other substances every month. If an egg (ovum) has been fertilized (zygote), pregnancy occurs, the fertilized egg (zygote) will burrow into the endometrium in your uterus, where it will stay for the rest of its growth, growing into a fetus and then a baby. Your uterus (womb) will expand during a pregnancy to make room for the growing fetus. A part of the wall of the fertilized egg (zygote), which has burrowed into the endometrium, develops into the placenta. If an egg has not been fertilized, the endometrial lining is shed at the end of each menstrual cycle, this lining flows out of your body. This is known as menstruation or your period.

- The myometrium is the large middle layer of your uterus, which is made up of interlocking groups of muscle. It plays an important role during the birth of a baby, contracting rhythmically to move the baby out of the body via the birth canal (vagina).

- Cervix is the lower part of your uterus, that connects your uterus to your vagina.

- Vagina is a muscular tube connecting your cervix to the outside of your body (the vestibule of the vulva). Your vagina receives the penis and semen during sexual intercourse and also provides a passageway for menstrual blood flow to leave the body.

The female reproductive system also plays an important part in pregnancy and birth.

Figure 1. Female reproductive system (normal female reproductive system anatomy)

Figure 2. Female reproductive system

What are the ovaries?

Ovaries are female reproductive glands found only in females (women). The 2 ovaries (one ovary is on each side of your uterus or womb) produce female hormones (estrogen and progesterone) and eggs (ova) for reproduction. The eggs travel from your ovaries through the fallopian tubes into your uterus (womb) where the fertilized egg settles in and develops into a fetus (unborn baby).

Your ovaries are held in place by various ligaments which anchor them to your uterus and the pelvis. The ovary contains ovarian follicles, in which eggs develop. Once a follicle is mature, it ruptures and the developing egg is ejected from the ovary into the fallopian tubes. This is called ovulation. Ovulation occurs in the middle of the menstrual cycle and usually takes place every 28 days or so in a mature female. It takes place from either the right or left ovary at random.

Your ovaries are mainly made up of 3 kinds of cells. Each type of cell can develop into a different type of tumor:

- Epithelial tumors start from the cells that cover the outer surface of the ovary. Most ovarian tumors are epithelial cell tumors.

- Germ cell tumors start from the cells that produce the eggs (ova).

- Stromal tumors start from structural tissue cells that hold the ovary together and produce the female hormones estrogen and progesterone.

Some of these tumors are benign (non-cancerous) and never spread beyond the ovary. Malignant (cancerous) or borderline (low malignant potential) ovarian tumors can spread (metastasize) to other parts of the body and can be fatal.

Figure 3. The ovaries lie in shallow depressions in the lateral wall of the pelvic cavity

Figure 4. Ovary blood supply

Figure 5. Ovary anatomy

Ovarian cancer types

Your ovaries are made up of different types of cells. The type of ovarian cancer you have depends on the type of cell it starts in.

The main types of ovarian cancer are 3:

- Epithelial ovarian cancers which start in the surface layer which covers the ovary, fallopian tube or peritoneum.

- Germ cell ovarian cancer which begins in the cells that develop into eggs.

- Sex cord stromal cancers which begin in the tissues that support your ovaries and produce hormones.

Knowing which type of ovarian cancer you have helps your doctors decide what treatment you need.

Epithelial ovarian tumors

Epithelial ovarian tumors start in the outer surface of the ovaries. These tumors can be benign (not cancer), borderline (low malignant potential), or malignant (cancer).

Benign epithelial ovarian tumors

Epithelial ovarian tumors that are benign don’t spread and usually don’t lead to serious illness. There are several types of benign epithelial tumors including serous cystadenomas, mucinous cystadenomas, and Brenner tumors.

Borderline epithelial tumors

When looked at in the lab, some ovarian epithelial tumors don’t clearly appear to be cancerous and are known as borderline epithelial ovarian cancer. Around 15 out of 100 ovarian tumors (15%) are borderline tumors. They are sometimes called atypical proliferative tumors or tumors of low malignant potential.

Borderline epithelial ovarian tumors are different to ovarian cancer because they don’t grow into the supportive tissue of the ovary (the stroma). They usually grow slowly and in a more controlled way than cancer cells.

Borderline epithelial ovarian tumors usually affect women aged between 20 and 40. They are usually diagnosed at an early stage. This means the abnormal cells are still within the ovary.

Sometimes abnormal cells break away from the tumor and settle elsewhere in the body. This is usually in the belly (abdomen). Very rarely, these cells start to grow into the underlying tissue.

There are different types of borderline ovarian tumors. The two most common types are atypical proliferative serous carcinoma and atypical proliferative mucinous carcinoma. These tumors were previously called tumors of low malignant potential (LMP tumors). These are different from typical ovarian cancers because they don’t grow into the supporting tissue of the ovary called the ovarian stroma. If they do spread outside the ovary, for example, into the abdominal cavity (belly), they might grow on the lining of the abdomen but not into it.

These tumors grow slowly and are less life-threatening than most ovarian cancers.

Malignant epithelial ovarian tumors

Cancerous epithelial tumors are called carcinomas. About 85% to 90% of malignant ovarian cancers are epithelial ovarian carcinomas. These tumor cells have several features (when looked at in the lab) that can be used to classify epithelial ovarian carcinomas into different types. The serous type is by far the most common, and can include high grade and low grade tumors. The other main types include mucinous, endometrioid, and clear cell.

- Serous carcinomas (52%)

- High grade serous carcinoma is the most common type of epithelial ovarian cancer. It can affect the ovaries, fallopian tubes or the peritoneum. Doctors think that most high grade serous carcinomas start in the cells at the end of the fallopian tube (fimbriae). These early cancer cells then spread to the ovary and grow. So they might sometimes be called fallopian tube cancer or tubo ovarian cancer.

- Low grade serous ovarian cancers are rare. They are usually diagnosed in younger people and are slow growing. Chemotherapy doesn’t tend to work as well as it does for other types of epithelial ovarian cancer.

- Endometroid carcinoma (10%)

- Endometrioid ovarian cancer is the 2nd most common type of epithelial ovarian cancer. It can be linked to endometriosis. Most cases of endometrioid ovarian cancer are diagnosed at an early stage and are low grade. Some women have endometroid ovarian cancer at the same time as a separate womb (endometrial) cancer.

- Clear cell carcinoma (6%)

- Clear cell ovarian cancer can also be linked to endometriosis. The treatment is the same as for high grade serous ovarian cancer. But chemotherapy doesn’t tend to work as well as it does for other types of epithelial ovarian cancer.

- Mucinous carcinoma (6%)

- Mucinous ovarian cancer is rare. It can be difficult to diagnose. The doctor does tests to check if the cancer started to grow in the ovary. Or if it spread there from somewhere else in your digestive system. Chemotherapy doesn’t tend to work as well for mucinous ovarian cancer. Mucinous tumors can be one of the following:

- non-cancerous (benign)

- borderline (contain abnormal cells but are not a cancer)

- cancerous (malignant)

- Mucinous ovarian cancer is rare. It can be difficult to diagnose. The doctor does tests to check if the cancer started to grow in the ovary. Or if it spread there from somewhere else in your digestive system. Chemotherapy doesn’t tend to work as well for mucinous ovarian cancer. Mucinous tumors can be one of the following:

- Undifferentiated or unclassifiable

- Some epithelial ovarian cancers are undifferentiated or unclassifiable. These cancers have cells that are very undeveloped. So it is not possible to tell which type of cell the cancer started from.

Each ovarian cancer is given a grade, based on how much the tumor cells look like normal tissue:

- Grade 1 epithelial ovarian carcinomas look more like normal tissue and tend to have a better prognosis (outlook).

- Grade 3 epithelial ovarian carcinomas look less like normal tissue and usually have a worse outlook.

Other traits are also taken into account, such as how fast the cancer cells grow and how well they respond to chemotherapy, to come up with the tumor’s type:

- Type 1 tumors tend to grow slowly and cause fewer symptoms. These tumors also seem not to respond well to chemotherapy. Low grade (grade 1) serous carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma, mucinous carcinoma and endometroid carcinoma are examples of type 1 tumors.

- Type 2 tumors grow fast and tend to spread sooner. These tumors tend to respond better to chemotherapy. High grade (grade 3) serous carcinoma is an example of a type 2 tumor.

Other cancers that are similar to epithelial ovarian cancer

Primary peritoneal carcinoma

Primary peritoneal carcinoma is a rare cancer closely related to epithelial ovarian cancer. At surgery, it looks the same as an epithelial ovarian cancer that has spread through the abdomen. In the lab, primary peritoneal carcinoma also looks just like epithelial ovarian cancer. Other names for this cancer include extra-ovarian (meaning outside the ovary) primary peritoneal carcinoma and serous surface papillary carcinoma.

Primary peritoneal carcinoma appears to start in the cells lining the inside of the fallopian tubes.

Like ovarian cancer, primary peritoneal carcinoma tends to spread along the surfaces of the pelvis and abdomen, so it is often difficult to tell exactly where the cancer first started. This type of cancer can occur in women who still have their ovaries, but it is of more concern for women who have had their ovaries removed to prevent ovarian cancer. This cancer does rarely occur in men.

Symptoms of primary peritoneal carcinoma are similar to those of ovarian cancer, including abdominal pain or bloating, nausea, vomiting, indigestion, and a change in bowel habits. Also, like ovarian cancer, primary peritoneal carcinoma may elevate the blood level of a tumor marker called CA-125.

Women with primary peritoneal carcinoma usually get the same treatment as those with widespread ovarian cancer. This could include surgery to remove as much of the cancer as possible (a process called debulking that is discussed in the section about surgery), followed by chemotherapy like that given for ovarian cancer. Its outlook is likely to be similar to widespread ovarian cancer.

Fallopian tube cancer

This is another rare cancer that is similar to epithelial ovarian cancer. It begins in the tube that carries an egg from the ovary to the uterus (the fallopian tube). Like primary peritoneal carcinoma, fallopian tube cancer and ovarian cancer have similar symptoms. The treatment for fallopian tube cancer is much like that for ovarian cancer, but the outlook (prognosis) is slightly better.

Ovarian germ cell tumors

Germ cells usually form the ova or eggs in females and the sperm in males. Germ cell ovarian tumors begin in the ovarian cells that develop into eggs (germ cells). They are rare and usually affect people up to their early 30s. Less than 2% of ovarian cancers are germ cell tumors. Most ovarian germ cell tumors are benign, but some are cancerous and may be life threatening. Overall, they have a good outlook, with more than 9 out of 10 patients surviving at least 5 years after diagnosis. You usually have surgery to remove the tumor. You might have chemotherapy if your tumor is cancerous. Treatment usually works well and most women are cured.

There are several subtypes of germ cell tumors. They can be non cancerous (benign) or cancerous (malignant).

Benign germ cell ovarian tumors

- Mature teratomas also called ovarian dermoid cysts are the most common type of ovarian germ cell tumor. They are non cancerous (benign). They are most common in women during their teens to their forties.

Malignant germ cell ovarian tumors

- These tumors contain cancer cells. There are different types including:

- immature teratomas

- dysgerminoma

- yolk sac tumor

- non gestational choriocarcinoma

- embryonal carcinoma

The most common germ cell tumors are teratomas, dysgerminomas, endodermal sinus tumors, and choriocarcinomas. Germ cell tumors can also be a mix of more than a single subtype.

Teratoma

Teratomas are germ cell tumors with areas that, when seen under the microscope, look like each of the 3 layers of a developing embryo: the endoderm (innermost layer), mesoderm (middle layer), and ectoderm (outer layer). This germ cell tumor has a benign form called mature teratoma and a cancerous form called immature teratoma.

The mature teratoma is by far the most common ovarian germ cell tumor. It is a benign tumor that usually affects women of reproductive age (teens through forties). It is often called a dermoid cyst because its lining is made up of tissue similar to skin (dermis). These tumors or cysts can contain different kinds of benign tissues including, bone, hair, and teeth. The patient is cured by surgical removal of the cyst, but sometimes a new cyst develops later in the other ovary.

Immature teratomas are a type of cancer. They occur in girls and young women, usually younger than 18. These are rare cancers that contain cells that look like those from embryonic or fetal tissues such as connective tissue, respiratory passages, and brain. Tumors that are relatively more mature (called grade 1 immature teratoma) and haven’t spread beyond the ovary are treated by surgical removal of the ovary. When they have spread beyond the ovary and/or much of the tumor has a very immature appearance (grade 2 or 3 immature teratomas), chemotherapy is recommended in addition to surgery.

Dysgerminoma

This type of cancer is rare, but it is the most common ovarian germ cell cancer. It usually affects women in their teens and twenties. Dysgerminomas are considered malignant (cancerous), but most don’t grow or spread very rapidly. When they are limited to the ovary, more than 75% of patients are cured by surgically removing the ovary, without any further treatment. Even when the tumor has spread further (or if it comes back later), surgery, radiation therapy, and/or chemotherapy are effective in controlling or curing the disease in about 90% of patients.

Endodermal sinus tumor (yolk sac tumor) and choriocarcinoma

These very rare tumors typically affect girls and young women. They tend to grow and spread rapidly but are usually very sensitive to chemotherapy. Choriocarcinoma that starts in the placenta (during pregnancy) is more common than the kind that starts in the ovary. Placental choriocarcinomas usually respond better to chemotherapy than ovarian choriocarcinomas do.

Ovarian stromal tumors

About 1% of ovarian cancers are ovarian stromal cell tumors. More than half of stromal tumors are found in women older than 50, but about 5% of stromal tumors occur in young girls.

The most common symptom of these tumors is abnormal vaginal bleeding. This happens because many of these tumors produce female hormones (estrogen). These hormones can cause vaginal bleeding (like a period) to start again after menopause. In young girls, these tumors can also cause menstrual periods and breast development to occur before puberty.

Less often, stromal tumors make male hormones (like testosterone). If male hormones are produced, the tumors can cause normal menstrual periods to stop. They can also make facial and body hair grow. If the stromal tumor starts to bleed, it can cause sudden, severe abdominal pain.

Types of malignant (cancerous) stromal tumors include granulosa cell tumors (the most common type), granulosa-theca tumors, and Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors, which are usually considered low-grade cancers. Thecomas and fibromas are benign stromal tumors. Cancerous stromal tumors are often found at an early stage and have a good outlook, with more than 75% of patients surviving long-term.

Ovarian cysts

An ovarian cyst is a collection of fluid inside an ovary. Most ovarian cysts occur as a normal part of the process of ovulation (egg release) — these are called functional cysts. These cysts usually go away within a few months without any treatment. If you develop a cyst, your doctor may want to check it again after your next menstrual cycle (period) to see if it has gotten smaller.

An ovarian cyst can be more concerning in a female who isn’t ovulating (like a woman after menopause or a girl who hasn’t started her periods), and the doctor may want to do more tests. The doctor may also order other tests if the cyst is large or if it does not go away in a few months. Even though most of these cysts are benign (not cancer), a small number of them could be cancer. Sometimes the only way to know for sure if the cyst is cancer is to take it out with surgery. Cysts that appear to be benign (based on how they look on imaging tests) can be observed (with repeated physical exams and imaging tests), or removed with surgery.

Ovarian cancer signs and symptoms

Early-stage ovarian cancer rarely causes any symptoms. Advanced-stage ovarian cancer may cause few and nonspecific symptoms that are often mistaken for more common benign conditions.

Signs and symptoms of ovarian cancer may include:

- Abdominal bloating or swelling

- Quickly feeling full when eating

- Weight loss

- Discomfort in the pelvis area

- Changes in bowel habits, such as constipation

- A frequent need to urinate

These symptoms are also commonly caused by benign (non-cancerous) diseases and by cancers of other organs. When they are caused by ovarian cancer, they tend to be persistent and a change from normal − for example, they occur more often or are more severe. These symptoms are more likely to be caused by other conditions, and most of them occur just about as often in women who don’t have ovarian cancer. But if you have these symptoms more than 12 times a month, see your doctor so the problem can be found and treated if necessary.

Others symptoms of ovarian cancer can include:

- Fatigue (extreme tiredness)

- Upset stomach

- Back pain

- Pain during sex

- Constipation

- Changes in a woman’s period, such as heavier bleeding than normal or irregular bleeding

- Abdominal (belly) swelling with weight loss

Early symptoms of ovarian cancer

The symptoms of ovarian cancer can be difficult to recognize, particularly in the early stages of the disease. They are often the same as the symptoms of other, less serious, conditions, such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or premenstrual syndrome (PMS). However, the most common symptoms that may indicate ovarian cancer are:

- abdominal bloating or feeling full

- abdominal or back pain

- appetite loss or feeling full quickly

- changes in toilet habits

- needing to urinate more often

- unexplained weight loss or weight gain

- indigestion or heartburn

- fatigue

- bleeding in-between periods or after menopause

- indigestion or nausea

- pain during intercourse

If any of these symptoms are unusual for you, and they persist, it’s important to see your doctor. Many of these symptoms may be the result of other conditions in the pelvic area.

If you have any of these symptoms, keep a symptom diary to see how many of these symptoms you have over a longer period. Bear in mind that ovarian cancer is rare in women under 40 years of age. If you regularly have any of these symptoms, talk to your doctor. It’s unlikely that they are being caused by a serious problem, but it’s best to be checked.

If you’ve already seen your doctor and the symptoms continue or get worse, it is important to go back and explain this, as you know your body better than anyone.

Can ovarian cancer be found early?

Only about 20% of ovarian cancers are found at an early stage. When ovarian cancer is found early, about 94% of patients live longer than 5 years after diagnosis.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends that if you (especially if 50 or over) have the following symptoms on a persistent or frequent basis – particularly more than 12 times per month, your doctor should arrange tests – especially if you’re are over 50 4:

- persistent swollen tummy (abdomen) or bloating

- feeling full (early satiety) and/or loss of appetite

- pelvic or abdominal pain

- increased urinary urgency and/or frequency.

First tests:

- Measure serum cancer antigen 125 (CA125) in primary care in women with symptoms that suggest ovarian cancer

- If serum CA125 is 35 IU/ml or greater, arrange an ultrasound scan of the abdomen and pelvis.

- For any woman who has normal serum CA125 (less than 35 IU/ml), or CA125 of 35 IU/ml or greater but a normal ultrasound:

- assess her carefully for other clinical causes of her symptoms and investigate if appropriate

- if no other clinical cause is apparent, advise her to return to her doctor if her symptoms become more frequent and/or persistent.

Ways to find ovarian cancer early

Regular women’s health exams

During a pelvic exam, the health care professional feels the ovaries and uterus for size, shape, and consistency. A pelvic exam can be useful because it can find some female cancers at an early stage, but most early ovarian tumors are difficult or impossible to feel. Pelvic exams may, however, help find other cancers or female conditions. Women should discuss the need for these exams with their doctor.

The Pap test is effective in early detection of cervical cancer, but it isn’t a test for ovarian cancer. Rarely, ovarian cancers are found through Pap tests, but usually they are at an advanced stage.

See a doctor if you have symptoms

Early cancers of the ovaries often cause no symptoms. Symptoms of ovarian cancer can also be caused by other, less serious conditions. By the time ovarian cancer is considered as a possible cause of these symptoms, it usually has already spread. Also, some types of ovarian cancer can rapidly spread to nearby organs. Prompt attention to symptoms may improve the odds of early diagnosis and successful treatment. If you have symptoms similar to those of ovarian cancer almost daily for more than a few weeks, report them right away to your health care professional.

Screening tests for ovarian cancer

Screening tests and exams are used to detect a disease, like cancer, in people who don’t have any symptoms. (For example, a mammogram can often detect breast cancer in its earliest stage, even before a doctor can feel the cancer.)

There has been a lot of research to develop a screening test for ovarian cancer, but there hasn’t been much success so far. The 2 tests used most often (in addition to a complete pelvic exam) to screen for ovarian cancer are transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) and the CA-125 blood test.

- TVUS (transvaginal ultrasound) is a test that uses sound waves to look at the uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries by putting an ultrasound wand into the vagina. It can help find a mass (tumor) in the ovary, but it can’t actually tell if a mass is cancer or benign. When it is used for screening, most of the masses found are not cancer.

- CA-125 blood test measures the amount of a protein called CA-125 in your blood. Many women with ovarian cancer have high levels of CA-125. This test can be useful as a tumor marker to help guide treatment in women known to have ovarian cancer, because a high level often goes down if treatment is working. But checking CA-125 levels has not been found to be as useful as a screening test for ovarian cancer. The problem with using this test for ovarian cancer screening is that high levels of CA-125 is more often caused by common conditions such as endometriosis and pelvic inflammatory disease. Also, not everyone who has ovarian cancer has a high CA-125 level. When someone who is not known to have ovarian cancer has an abnormal CA-125 level, the doctor might repeat the test (to make sure the result is correct) and may consider ordering a transvaginal ultrasound test.

Better ways to screen for ovarian cancer are being researched but currently there are no reliable screening tests. Hopefully, improvements in screening tests will eventually lead to fewer deaths from ovarian cancer.

If you’re at average risk

There are no recommended screening tests for ovarian cancer for women who do not have symptoms and are not at high risk of developing ovarian cancer. In studies of women at average risk of ovarian cancer, using transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) and CA-125 for screening led to more testing and sometimes more surgeries, but did not lower the number of deaths caused by ovarian cancer. For that reason, no major medical or professional organization recommends the routine use of transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) or the CA-125 blood test to screen for ovarian cancer in women at average risk.

If you’re at high risk

Some organizations state that transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) and CA-125 may be offered to screen women who have a high risk of ovarian cancer due to an inherited genetic syndrome such as Lynch syndrome, BRCA gene mutations or a strong family history of breast and ovarian cancer. Still, even in these women, it has not been proven that using these tests for screening lowers their chances of dying from ovarian cancer.

Screening tests for germ cell tumors/stromal tumors

There are no recommended screening tests for germ cell tumors or stromal tumors. Some germ cell cancers release certain protein markers such as human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) into the blood. After these tumors have been treated by surgery and chemotherapy, blood tests for these markers can be used to see if treatment is working and to determine if the cancer is coming back.

Ovarian cancer causes

Scientists don’t yet know exactly what causes most ovarian cancers. Scientists do know some risk factors that make a woman more likely to develop epithelial ovarian cancer. Much less is known about risk factors for germ cell and stromal tumors of the ovaries.

The most recent and important finding about the cause of ovarian cancer is that it starts in cells at the tail ends of the fallopian tubes and not necessarily in the ovary itself. This new information may open more research studies looking at preventing and screening for this type of cancer.

There are many theories about the causes of ovarian cancer. Some of them came from looking at the things that change the risk of ovarian cancer. For example, pregnancy and taking birth control pills both lower the risk of ovarian cancer. Since both of these things reduce the number of times the ovary releases an egg (ovulation), some researchers think that there may be some relationship between ovulation and the risk of developing ovarian cancer.

Also, experts know that tubal ligation and hysterectomy lower the risk of ovarian cancer. One theory to explain this is that some cancer-causing substances may enter the body through the vagina and pass through the uterus and fallopian tubes to reach the ovaries. This would explain how removing the uterus or blocking the fallopian tubes affects ovarian cancer risk.

Another theory is that male hormones (androgens) can cause ovarian cancer.

Researchers have made great progress in understanding how certain mutations (changes) in DNA can cause normal cells to become cancerous. DNA is the chemical that carries the instructions for nearly everything your cells do. You usually look like your parents because they are the source of your DNA. However, DNA affects more than the way you look. Some genes (parts of your DNA) contain instructions for controlling when our cells grow and divide. Mutations in these genes can lead to the development of cancer.

Inherited genetic mutations

Between 5 and 15 out of 100 ovarian cancers (5 to 15%) are caused by an inherited faulty gene. Inherited genes that increase the risk of ovarian cancer include faulty versions of BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. Faults in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes also increase the risk of breast cancer.

Other inherited faulty genes such as PTEN (PTEN tumor hamartoma syndrome), STK11 (Peutz-Jeghers syndrome), MUTYH (MUTYH-asociated polyposis, and the many genes that can cause hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer (MLH1, MLH3, MSH2, MSH6, TGFBR2, PMS1, and PMS2) are related to other family cancer syndromes and linked to an increased risk of ovarian cancer.

Besides the gene mutations mentioned above, there are other genes linked to ovarian cancer. These include ATM, BRIP1, RAD51C, RAD51D, and PALB2. Some of these genes are also associated with cancers such as breast and pancreas.

Having relatives with ovarian cancer does not necessarily mean that you have a faulty inherited gene in the family. The cancers could have happened by chance. But women with a mother or sister diagnosed with ovarian cancer have around 3 times the risk of ovarian cancer. This is compared to women without a family history.

Genetic tests can detect mutations associated with these inherited syndromes. If you have a family history of cancers linked to these syndromes, such as breast and ovarian cancers, thyroid and ovarian cancer, and/or colorectal and endometrial (uterine) cancer, you might want to ask your doctor about genetic counseling and testing. The American Cancer Society recommends discussing genetic testing with a qualified cancer genetics professional before any genetic testing is done.

Resources for locating a genetics professional in your community are available online:

- The National Society of Genetic Counselors (https://findageneticcounselor.nsgc.org) offers a searchable directory of genetic counselors in the United States and Canada. You can search by location, name, area of practice/specialization, and/or ZIP Code.

- The American Board of Genetic Counseling (https://abgc.learningbuilder.com/Search/Public/MemberRole/Verification) provides a searchable directory of certified genetic counselors worldwide. You can search by practice area, name, organization, or location.

- The Canadian Association of Genetic Counselors (https://www.cagc-accg.ca/index.php?page=225) has a searchable directory of genetic counselors in Canada. You can search by name, distance from an address, province, or services.

- The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (https://www.acmg.net/ACMG/Directories.aspx) has a searchable database of medical genetics clinic services in the United States.

Acquired genetic changes

Most mutations related to ovarian cancer are not inherited but instead occur during a woman’s life and are called acquired mutations. In some cancers, these types of mutations leading to the development of cancer may result from radiation or cancer-causing chemicals, but there is no evidence for this in ovarian cancer. So far, studies haven’t been able to specifically link any single chemical in the environment or in our diets to mutations that cause ovarian cancer. The cause of most acquired mutations remains unknown.

Most ovarian cancers have several acquired mutations. Research has suggested that tests to identify acquired mutations in ovarian cancers, like the TP53 tumor suppressor gene or the HER2 oncogene, can help predict a woman’s prognosis. The role of these tests is still not certain, and more research is needed.

Ovarian cancer risk factors

A risk factor is anything that increases your chance of getting a disease like cancer. Generally, it’s not possible to say what causes ovarian cancer in an individual woman. However, some features are more common among women who have developed ovarian cancer. These features are called risk factors. Having certain risk factors increases a woman’s chance of developing ovarian cancer.

Having one or more risk factors for ovarian cancer doesn’t mean a woman will definitely develop ovarian cancer. In fact, many women with ovarian cancer have no obvious risk factors.

Factors that increase your risk of ovarian cancers

Getting older

The risk of developing ovarian cancer gets higher with age. Ovarian cancer is rare in women younger than 40. The risk of ovarian cancer increases steeply from around 45 years. Most ovarian cancers develop after menopause. And is greatest in those aged between 75 and 79 years. Half of all ovarian cancers are found in women 63 years of age or older.

Being overweight or obese

Obesity has been linked to a higher risk of developing many cancers. The current information available for ovarian cancer risk and obesity is not clear. Obese women (those with a body mass index [BMI] of at least 30) may have a higher risk of developing ovarian cancer, but not necessarily the most aggressive types, such as high grade serous cancers. Obesity may also affect the overall survival of a woman with ovarian cancer.

Having children later or never having a full-term pregnancy

Women who have their first full-term pregnancy after age 35 or who never carried a pregnancy to term have a higher risk of ovarian cancer.

Using fertility treatment

Fertility treatment with in vitro fertilization (IVF) seems to increase the risk of the type of ovarian tumors known as “borderline” or “low malignant potential” (LMP tumors). Other studies, however, have not shown an increased risk of invasive ovarian cancer with fertility drugs. If you are taking fertility drugs, you should discuss the potential risks with your doctor.

Taking hormone therapy after menopause

Women using estrogens after menopause have an increased risk of developing ovarian cancer. The risk seems to be higher in women taking estrogen alone (without progesterone) for many years (at least 5 or 10). The increased risk is less certain for women taking both estrogen and progesterone.

Having a family history of ovarian cancer, breast cancer, or colorectal cancer

Ovarian cancer can run in families. Your ovarian cancer risk is increased if your mother, sister, or daughter has (or has had) ovarian cancer. The risk also gets higher the more relatives you have with ovarian cancer. Increased risk for ovarian cancer can also come from your father’s side.

A family history of some other types of cancer such as colorectal and breast cancer is linked to an increased risk of ovarian cancer. This is because these cancers can be caused by an inherited mutation (change) in certain genes that cause a family cancer syndrome that increases the risk of ovarian cancer.

Having a family cancer syndrome

About 5 to 10% of ovarian cancers are a part of family cancer syndromes resulting from inherited changes (mutations) in certain genes.

Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome

This syndrome is caused by inherited mutations in the genes BRCA1 and BRCA2, as well as possibly some other genes that have not yet been found. This syndrome is linked to a high risk of breast cancer as well as ovarian, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal cancers. The risk of some other cancers, such as pancreatic cancer and prostate cancer, are also increased.

Mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 are also responsible for most inherited ovarian cancers. Mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 are about 10 times more common in those who are Ashkenazi Jewish than those in the general U.S. population.

The lifetime ovarian cancer risk for women with a BRCA1 mutation is estimated to be between 35% and 70%. This means that if 100 women had a BRCA1 mutation, between 35 and 70 of them would get ovarian cancer. For women with BRCA2 mutations the risk has been estimated to be between 10% and 30% by age 70. These mutations also increase the risks for primary peritoneal carcinoma and fallopian tube carcinoma.

In comparison, the ovarian cancer lifetime risk for the women in the general population is less than 2%.

PTEN tumor hamartoma syndrome

In this syndrome, also known as Cowden disease, people are primarily affected with thyroid problems, thyroid cancer, and breast cancer. Women also have an increased risk of endometrial and ovarian cancer. It is caused by inherited mutations in the PTEN gene.

Hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer

Women with this syndrome have a very high risk of colon cancer and also have an increased risk of developing cancer of the uterus (endometrial cancer) and ovarian cancer. Many different genes can cause this syndrome. They include MLH1, MLH3, MSH2, MSH6, TGFBR2, PMS1, and PMS2. The lifetime risk of ovarian cancer in women with hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer (Lynch syndrome) is about 10%. Up to 1% of all ovarian epithelial cancers occur in women with hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer (Lynch syndrome).

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome

People with this rare genetic syndrome develop polyps in the stomach and intestine while they are teenagers. They also have a high risk of cancer, particularly cancers of the digestive tract (esophagus, stomach, small intestine, colon). Women with this syndrome have an increased risk of ovarian cancer, including both epithelial ovarian cancer and a type of stromal tumor called sex cord tumor with annular tubules (SCTAT). This syndrome is caused by mutations in the gene STK11.

MUTYH-associated polyposis

People with this syndrome develop polyps in the colon and small intestine and have a high risk of colon cancer. They are also more likely to develop other cancers, including cancers of the ovary and bladder. This syndrome is caused by mutations in the gene MUTYH.

Having had breast cancer

If you have had breast cancer, you might also have an increased risk of developing ovarian cancer. There are several reasons for this. Some of the reproductive risk factors for ovarian cancer may also affect breast cancer risk. The risk of ovarian cancer after breast cancer is highest in those women with a family history of breast cancer. A strong family history of breast cancer may be caused by an inherited mutation in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes and hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome, which is linked to an increased risk of ovarian cancer.

Endometriosis or diabetes

Studies have shown that women with endometriosis or diabetes have an increased risk of ovarian cancer. In diabetics, the increase in risk might be higher in those that use insulin.

Smoking and alcohol use

Smoking doesn’t increase the risk of ovarian cancer overall, but it is linked to an increased risk for the mucinous ovarian cancer. The longer you have smoked, the greater your risk.

Drinking alcohol is not linked to ovarian cancer risk.

Asbestos

Asbestos is an insulating material that’s heat and fire resistant. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classify asbestos as a cause of ovarian cancer. The use of asbestos was banned in the late 1990s in the US. Asbestos was widely used in:

- building industry

- shipbuilding

- manufacturing of household appliances

- motor industry

- power stations

- telephone exchanges

There are 3 main types of asbestos – blue, brown and white.

Asbestos is made up of tiny fibers. You can breathe these fibers in when you come into contact with asbestos.

Factors with unclear effects on ovarian cancer risk

Androgens

Androgens, such as testosterone, are male hormones. There appears to be a link between certain androgens and specific types of ovarian cancer, but further studies of the role of androgens in ovarian cancer are needed.

Talcum powder

It has been suggested that talcum powder might cause cancer in the ovaries if the powder particles (applied to the genital area or on sanitary napkins, diaphragms, or condoms) were to travel through the vagina, uterus, and fallopian tubes to the ovary.

Many studies in women have looked at the possible link between talcum powder and cancer of the ovary. Findings have been mixed, with some studies reporting a slightly increased risk and some reporting no increase. Many case-control studies have found a small increase in risk. But these types of studies can be biased because they often rely on a person’s memory of talc use many years earlier. One prospective cohort study, which would not have the same type of potential bias, has not found an increased risk. A second found a modest increase in risk of one type of ovarian cancer.

For any individual woman, if there is an increased risk, the overall increase is likely to very be small. Still, talc is widely used in many products, so it is important to determine if the increased risk is real. Research in this area continues.

Diet

Some studies have shown a reduced rate of ovarian cancer in women who ate a diet high in vegetables or a low fat diet, but other studies disagree. The American Cancer Society recommends eating a variety of healthful foods, with an emphasis on plant sources. Eat at least 2 ½ cups of fruits and vegetables every day, as well as several servings of whole grain foods from plant sources such as breads, cereals, grain products, rice, pasta, or beans. Limit the amount of red meat and processed meats you eat. Even though the effect of these dietary recommendations on ovarian cancer risk remains uncertain, following them can help prevent several other diseases, including some other types of cancer.

Factors that can lower risk of ovarian cancer

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

Women who have been pregnant and carried it to term before age 26 have a lower risk of ovarian cancer than women who have not. The risk goes down with each full-term pregnancy. Breastfeeding may lower the risk even further.

Birth control

Women who have used oral contraceptives also known as birth control pills or the pill have a lower risk of ovarian cancer. The risk is lower the longer the pills are used. This lower risk continues for many years after the pill is stopped. Other forms of birth control such as tubal ligation (having fallopian tubes tied) and short use of IUDs (intrauterine devices) have also been associated with a lower risk of ovarian cancer.

Having a hysterectomy or having your tubes tied

Having your tubes tied because you don’t want any more pregnancies is called sterilization. Studies have found that having your fallopian tubes tied reduces your risk of ovarian cancer.

Until recently, most research has shown that having your womb removed (hysterectomy) may also reduce your risk of ovarian cancer. But this has become less clear in recent years. It might depend on several factors including your age when you had the operation. Any reduction in risk may be greater for younger women. Researchers continue to study this area.

A hysterectomy (removing the uterus without removing the ovaries) also seems to reduce the risk of getting ovarian cancer by about one-third.

Ovarian cancer prevention

Most women have one or more risk factors for ovarian cancer. But most of the common factors only slightly increase your risk, so they only partly explain the frequency of the disease. So far, what is known about risk factors has not translated into practical ways to prevent most cases of ovarian cancer.

There are several ways you can reduce your risk of developing the most common type of ovarian cancer, epithelial ovarian cancer. Much less is known about ways to lower the risk of developing germ cell and stromal tumors of the ovaries, so this information does not apply to those types. It is important to realize that some of these strategies lower your risk only slightly, while others lower it much more. Some strategies are easily followed, and others require surgery. If you are concerned about your risk of ovarian cancer, talk to your health care professionals. They can help you consider these ideas as they apply to your own situation.

Avoiding certain risk factors

Some risk factors for ovarian cancer, like getting older or having a family history, cannot be changed. But women might be able to lower their risk slightly by avoiding other risk factors, for example, by staying at a healthy weight, or not taking hormone replacement therapy after menopause.

Oral contraceptives

Using oral contraceptives (birth control pills) decreases the risk of developing ovarian cancer for average risk women and BRCA mutation carriers , especially among women who use them for several years. Women who used oral contraceptives for 5 or more years have about a 50% lower risk of developing ovarian cancer compared with women who never used oral contraceptives. Still, birth control pills do have some serious risks and side effects such as slightly increasing breast cancer risk. Women considering taking these drugs for any reason should first discuss the possible risks and benefits with their doctor.

Gynecologic surgery

Both tubal ligation and hysterectomy may reduce the chance of developing certain types of ovarian cancer, but experts agree that these operations should only be done for valid medical reasons — not for their effect on ovarian cancer risk.

If you are going to have a hysterectomy for a valid medical reason and you have a strong family history of ovarian or breast cancer, you may want to consider having both ovaries and fallopian tubes removed called a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy as part of that procedure.

Even if you don’t have an increased risk of ovarian cancer, some doctors recommend that the ovaries be removed with the uterus if a woman has already gone through menopause or is close to menopause. If you are older than 40 and you are going to have a hysterectomy, you should discuss the potential risks and benefits of having your ovaries removed with your doctor.

Another option for average risk women who do not wish to have their ovaries removed because they don’t want to lose ovarian function (and go through menopause early) is to have just the fallopian tubes removed (a bilateral salpingectomy) along with the uterus (a hysterectomy). They may choose to have their ovaries removed later. This has not been studied as well as removing both the ovaries and fallopian tubes at the same time, but there is enough information that it may be considered an option to reduce ovarian cancer risk in average risk women.

Prevention strategies for women with a family history of ovarian cancer or BRCA mutation

If your family history suggests that you (or a close relative) might have a syndrome linked with a high risk of ovarian cancer, you might want to consider genetic counseling and testing. During genetic counseling (by a genetic counselor or other health care professional with training in genetic risk evaluation), your personal medical and family history is reviewed. This can help predict whether you are likely to have one of the gene mutations associated with an increased ovarian cancer risk.

The counselor will also discuss the benefits and potential drawbacks of genetic testing with you. Genetic testing can help determine if you or members of your family carry certain gene mutations that cause a high risk of ovarian cancer. Still, the results are not always clear, and a genetic counselor can help you sort out what the results mean to you.

For some women with a strong family history of ovarian cancer, knowing they do not have a mutation that increases their ovarian cancer risk can be a great relief for them and their children. Knowing that you do have such a mutation can be stressful, but many women find this information very helpful in making important decisions about certain prevention strategies for them and their children.

Using oral contraceptives is one way that high risk women (women with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations) can reduce their risk of developing ovarian cancer. But birth control pills can increase breast cancer risk in women with or without these mutations. This increased risk appears highest while women are actively taking birth control pills but can continue even after stopping them. Research is continuing to find out more about the risks and benefits of oral contraceptives for women at high ovarian and breast cancer risk.

Tubal ligation may also effectively reduce the risk of ovarian cancer in women who have BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. Usually this type of surgery is not done alone and is typically done for reasons other than ovarian cancer prevention.

Sometimes a woman may want to consider having both ovaries and fallopian tubes removed (called a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy) to reduce her risk of ovarian cancer before cancer is even suspected. If the ovaries are removed to prevent ovarian cancer, the surgery is called risk-reducing or prophylactic. Generally, salpingo-oophorectomy may be recommended for high-risk women after they have finished having children. This operation lowers ovarian cancer risk a great deal but does not entirely eliminate it. That’s because some women who have a high risk of ovarian cancer already have a cancer at the time of surgery. These cancers can be so small that they are only found when the ovaries and fallopian tubes are looked at in the lab after they are removed. Also, women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutations have an increased risk of primary peritoneal carcinoma. Although the risk is low, this cancer can still develop after the ovaries and fallopian tubes are removed.

The risk of fallopian tube cancer is also increased in women with mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2. Sometimes early fallopian tube cancers are found unexpectedly when the fallopian tubes are removed as a part of a risk-reducing surgery. In fact, some cancers that were thought to be ovarian or primary peritoneal cancers may have actually started in the fallopian tubes. That is why experts recommend that women at high risk of ovarian cancer who are having their ovaries removed should have their fallopian tubes completely removed as well (salpingo-oophorectomy).

Research has shown that premenopausal women who have BRCA gene mutations and have had their ovaries removed reduce their risk of breast cancer as well as their risk of ovarian cancer. The risk of ovarian cancer is reduced by 85% to 95%, and the risk of breast cancer cut by 50% or more.

Some women who have a high risk of ovarian cancer due to BRCA gene mutations feel that having their ovaries and fallopian tubes removed is not right for them. Often doctors recommend that those women have screening tests to try to find ovarian cancer early.

Ovarian cancer diagnosis

If your doctor finds something suspicious during a pelvic exam, or if you have symptoms that might be due to ovarian cancer, your doctor, will recommend exams and tests to find the cause.

Medical history and physical exam

Your doctor will ask about your medical history to learn about possible risk factors, including your family history. You will also be asked if you’re having any symptoms, when they started, and how long you’ve had them. Your doctor will likely do a pelvic exam to check for an enlarged ovary or signs of fluid in the abdomen (which is called ascites). During a pelvic exam, your doctor inserts gloved fingers into your vagina and simultaneously presses a hand on your abdomen in order to feel (palpate) your pelvic organs. The doctor also visually examines your external genitalia, vagina and cervix.

If there is reason to suspect you have ovarian cancer based on your symptoms and/or physical exam, your doctor will order some tests to check further.

Surgery

Sometimes your doctor can’t be certain of your diagnosis until you undergo surgery to remove an ovary and have it tested for signs of cancer.

Consultation with a specialist

If the results of your pelvic exam or other tests suggest that you have ovarian cancer, you will need a doctor or surgeon who specializes in treating women with this type of cancer. A gynecologic oncologist is an obstetrician/gynecologist who is specially trained in treating cancers of the female reproductive system. Treatment by a gynecologic oncologist helps ensure that you get the best kind of surgery for your cancer. It has also has been shown to help patients with ovarian cancer live longer. Anyone suspected of having ovarian cancer should see this type of specialist before having surgery.

Ovarian cancer tests

Imaging tests

Doctors use imaging tests to take pictures of the inside of your body. Imaging tests can show whether a pelvic mass is present, but they cannot confirm that the mass is a cancer. These tests are also useful if your doctor is looking to see if ovarian cancer has spread (metastasized) to other tissues and organs.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound (ultrasonography) uses sound waves to create an image on a video screen. Sound waves are released from a small probe placed in the woman’s vagina and a small microphone-like instrument called a transducer gives off sound waves and picks up the echoes as they bounce off organs. A computer turns these echoes into an image on the screen.

Ultrasound is often the first test done if a problem with the ovaries is suspected. It can be used to find an ovarian tumor and to check if it is a solid mass (tumor) or a fluid-filled cyst. It can also be used to get a better look at the ovary to see how big it is and how it looks inside. This helps the doctor decide which masses or cysts are more worrisome.

Computed tomography (CT) scans

The CT scan is an x-ray test that makes detailed cross-sectional images of your body. The test can help tell if ovarian cancer has spread to other organs.

CT scans do not show small ovarian tumors well, but they can see larger tumors, and may be able to see if the tumor is growing into nearby structures. A CT scan may also find enlarged lymph nodes, signs of cancer spread to liver or other organs, or signs that an ovarian tumor is affecting your kidneys or bladder.

CT scans are not usually used to biopsy an ovarian tumor (see biopsy in the section “Other tests”), but they can be used to biopsy a suspected metastasis (area of spread). For this procedure, called a CT-guided needle biopsy, the patient stays on the CT scanning table, while a radiologist moves a biopsy needle toward the mass. CT scans are repeated until the doctors are confident that the needle is in the mass. A fine needle biopsy sample (tiny fragment of tissue) or a core needle biopsy sample (a thin cylinder of tissue about ½ inch long and less than 1/8 inch in diameter) is removed and examined in the lab.

Barium enema x-ray

A barium enema is a test to see if the cancer has invaded the colon (large intestine) or rectum. This test is rarely used for women with ovarian cancer. Colonoscopy may be done instead.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans

MRI scans also create cross-section pictures of your insides. But MRI uses strong magnets to make the images – not x-rays. A contrast material called gadolinium may be injected into a vein before the scan to see details better.

MRI scans are not used often to look for ovarian cancer, but they are particularly helpful to examine the brain and spinal cord where cancer could spread.

Chest x-ray

An x-ray might be done to determine whether ovarian cancer has spread (metastasized) to the lungs. This spread may cause one or more tumors in the lungs and more often causes fluid to collect around the lungs. This fluid, called a pleural effusion, can be seen with chest x-rays as well as other types of scans.

Positron emission tomography (PET) scan

For a PET scan, radioactive glucose (sugar) is given to look for the cancer. PET scans can help find cancer when it has spread, but are not used often to look for ovarian cancer. Body cells take in different amounts of the sugar, depending on how fast they are growing. Cancer cells, which grow quickly, are more likely to take up larger amounts of the sugar than normal cells. A special camera is used to create a picture of areas of radioactivity in the body.

The picture from a PET scan is not as detailed as a CT or MRI scan, but it provides helpful information about whether abnormal areas seen on these other tests are likely to be cancer or not.

If you have already been diagnosed with cancer, your doctor may use this test to see if the cancer has spread to lymph nodes or other parts of the body. A PET scan can also be useful if your doctor thinks the cancer may have spread but doesn’t know where.

PET/CT scan: Some machines can do both a PET and CT scan at the same time. This lets the doctor compare areas of higher radioactivity on the PET scan with the more detailed picture of that area on the CT scan.

Other tests

Laparoscopy

This procedure uses a thin, lighted tube through which a doctor can look at the ovaries and other pelvic organs and tissues in the area. The tube is inserted through a small incision (cut) in the lower abdomen and sends the images of the pelvis or abdomen to a video monitor. Laparoscopy provides a view of organs that can help plan surgery or other treatments and can help doctors confirm the stage (how far the tumor has spread) of the cancer. Also, doctors can manipulate small instruments through the laparoscopic incision(s) to perform biopsies.

Colonoscopy

A colonoscopy is a way to examine the inside of the large intestine (colon). The doctor looks at the entire length of the colon and rectum with a colonoscope, a thin, flexible, lighted tube with a small video camera on the end. It is inserted through the anus and into the rectum and the colon. Any abnormal areas seen can by biopsied. This procedure is more commonly used to look for colorectal cancer.

Biopsy

The only way to determine for certain if a growth is cancer is to remove a piece of it and examine it in the lab. This procedure is called a biopsy. For ovarian cancer, the biopsy is most commonly done by removing the tumor during surgery.

In rare cases, a suspected ovarian cancer may be biopsied during a laparoscopy procedure or with a needle placed directly into the tumor through the skin of the abdomen. Usually the needle will be guided by either ultrasound or CT scan. This is only done if you cannot have surgery because of advanced cancer or some other serious medical condition, because there is concern that a biopsy could spread the cancer.

If you have ascites (fluid buildup inside the abdomen), samples of the fluid can also be used to diagnose the cancer. In this procedure, called paracentesis, the skin of the abdomen is numbed and a needle attached to a syringe is passed through the abdominal wall into the fluid in the abdominal cavity. Ultrasound may be used to guide the needle. The fluid is taken up into the syringe and then sent for analysis to see if it contains cancer cells.

In all these procedures, the tissue or fluid obtained is sent to the lab. There it is examined by a pathologist, a doctor who specialize in diagnosing and classifying diseases by examining cells under a microscope and using other lab tests.

Blood tests

Your doctor will order blood count tests to make sure you have enough red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets (cells that help stop bleeding). There will also be tests to measure your kidney and liver function as well as your general health. The doctor will also order a CA-125 test. Women who have a high CA-125 level are often referred to a gynecologic oncologist, but any woman with suspected ovarian cancer should see a gynecologic oncologist, as well.

Some germ cell cancers can cause elevated blood levels of the tumor markers human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG), alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), and/or lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). These may be checked if your doctor suspects that your ovarian tumor could be a germ cell tumor.

Some ovarian stromal tumors cause the blood levels of a substance called inhibin and hormones such as estrogen and testosterone to go up. These levels may be checked if your doctor suspects that you have this type of tumor.

Lab tests for gene or protein changes

In some ovarian cancers, doctors might look for specific gene or protein changes in the cancer cells that could mean certain targeted or immunotherapy drugs might help treat the cancer. These tests can be done on a piece of the cancer taken during a biopsy or surgery for ovarian cancer.

- BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations: BRCA genes are normally involved in DNA repair, and mutations in these genes can cause cells to grow out of control and turn into cancer. Ovarian cancers with BRCA gene mutations are more likely to be helped by treatment with targeted drugs called PARP inhibitors.

- Folate receptor-alpha (FR-alpha) testing: In many ovarian cancers, the cells have high levels of the FR-alpha protein on their surfaces. Testing for FR-alpha levels can show if the cancer is more likely to respond to treatment with a targeted drug such as mirvetuximab soravtansine (Elahere).

- NTRK gene mutations: Some ovarian cancers might be tested for changes in one of the NTRK genes. Cells with these gene changes can lead to abnormal cell growth and cancer. Larotrectinib (Vitrakvi) and entrectinib (Rozlytrek) are targeted drugs that stop the proteins made by the abnormal NTRK genes. The number of ovarian cancers that have this mutation is very small, but this may be an option for some women.

- MSI and MMR gene testing: Women who have clear cell, endometrioid, or mucinous ovarian cancer might have their tumor tested to see if it shows high levels of gene changes called microsatellite instability (MSI). Testing might also be done to see if the cancer cells have changes in any of the mismatch repair (MMR) genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2). Changes in MSI or in MMR genes (or both) are often seen in people with Lynch syndrome (HNPCC). Up to 10% of all ovarian epithelial cancers have changes in these genes.

There are 2 possible reasons to test ovarian cancers for MSI or for MMR gene changes:

- To identify patients who should be tested for Lynch syndrome. A diagnosis of Lynch syndrome can help determine if a person should have screenings for other types of cancer, such as endometrial or colon cancer. If a person does have Lynch syndrome, their relatives could also have it, and may want to be tested for it.

- To determine treatment options for ovarian cancer. Ovarian cancers that have certain MSI or MMR gene changes might be treated with certain immunotherapy drugs known as checkpoint inhibitors.

Genetic counseling and testing if you have ovarian cancer

If you have been diagnosed with an epithelial ovarian cancer, your doctor will likely recommend that you get genetic counseling to help you decide if you should be tested for certain inherited gene changes, such as a mutation in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene. Some ovarian cancers are linked to mutations in these or other genes.

Genetic testing to look for inherited mutations can be helpful in several ways:

- If you are found to have a gene mutation, you might be more likely to get other types of cancer as well, so you might benefit from doing what you can to lower your risk of these cancers, as well as having tests to find them early.

- If you have a gene mutation, your family members (blood relatives) might also have it, so they can decide if they want to be tested to learn more about their cancer risk.

- If you have a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation, at some point you might benefit from treatment with targeted drugs called PARP inhibitors.

You may have heard about some home-based genetic tests. There is a concern that these tests are promoted by companies without giving full information. For example, a test for a small number of BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations has been approved by the FDA. However, there are more than 1,000 known BRCA mutations, and the ones included in the approved test are not the most common ones. This means there are many BRCA mutations that would not be detected by this test.

A genetic counselor or other qualified medical professional can help you understand the pros, cons, and possible limits of what genetic testing can tell you. This can help you decide if testing is right for you, and which testing is best.

Resources for locating a genetics professional in your community are available online: