Contents

- What is ovarian pain?

- Female reproductive system

- Ovarian pain causes

- Ovarian pain symptoms

- Ovarian pain diagnosis

- Ovarian pain treatment

- Ovarian cysts

- Ovarian torsion

- Ovarian cancer

- Ovarian cancer types

- Ovarian cancer causes

- Ovarian cancer risk factors

- Getting older

- Being overweight or obese

- Having children later or never having a full-term pregnancy

- Using fertility treatment

- Taking hormone therapy after menopause

- Having a family history of ovarian cancer, breast cancer, or colorectal cancer

- Having a family cancer syndrome

- Having had breast cancer

- Endometriosis or diabetes

- Smoking and alcohol use

- Asbestos

- Ovarian cancer signs and symptoms

- Can ovarian cancer be found early?

- Ovarian cancer diagnosis

- Ovarian cancer stages

- Grades of ovarian cancer

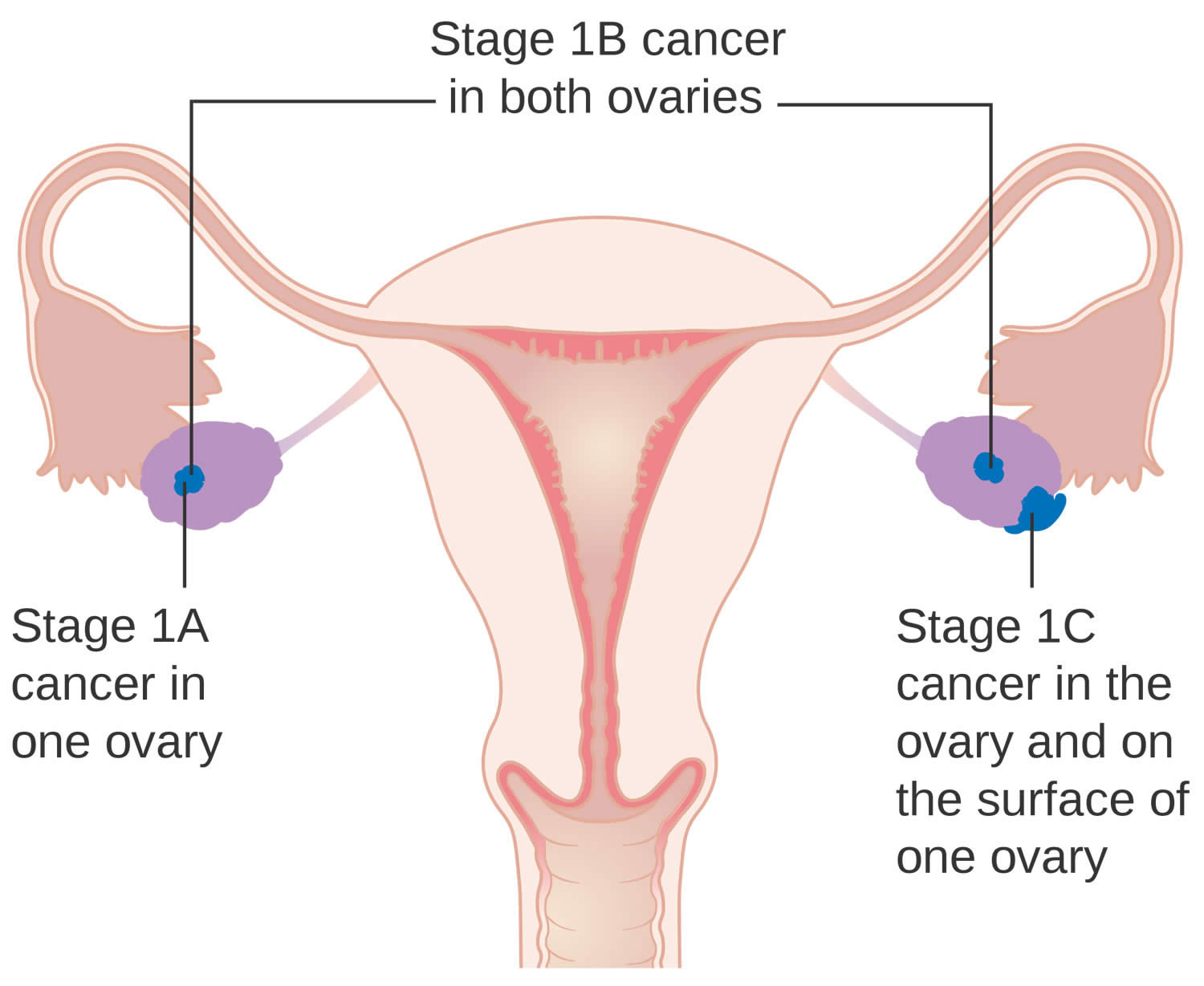

- Stage 1 ovarian cancer

- Stage 2 ovarian cancer

- Stage 3 ovarian cancer

- Stage 4 ovarian cancer

- Ovarian cancer treatment

- Ovarian cancer prognosis

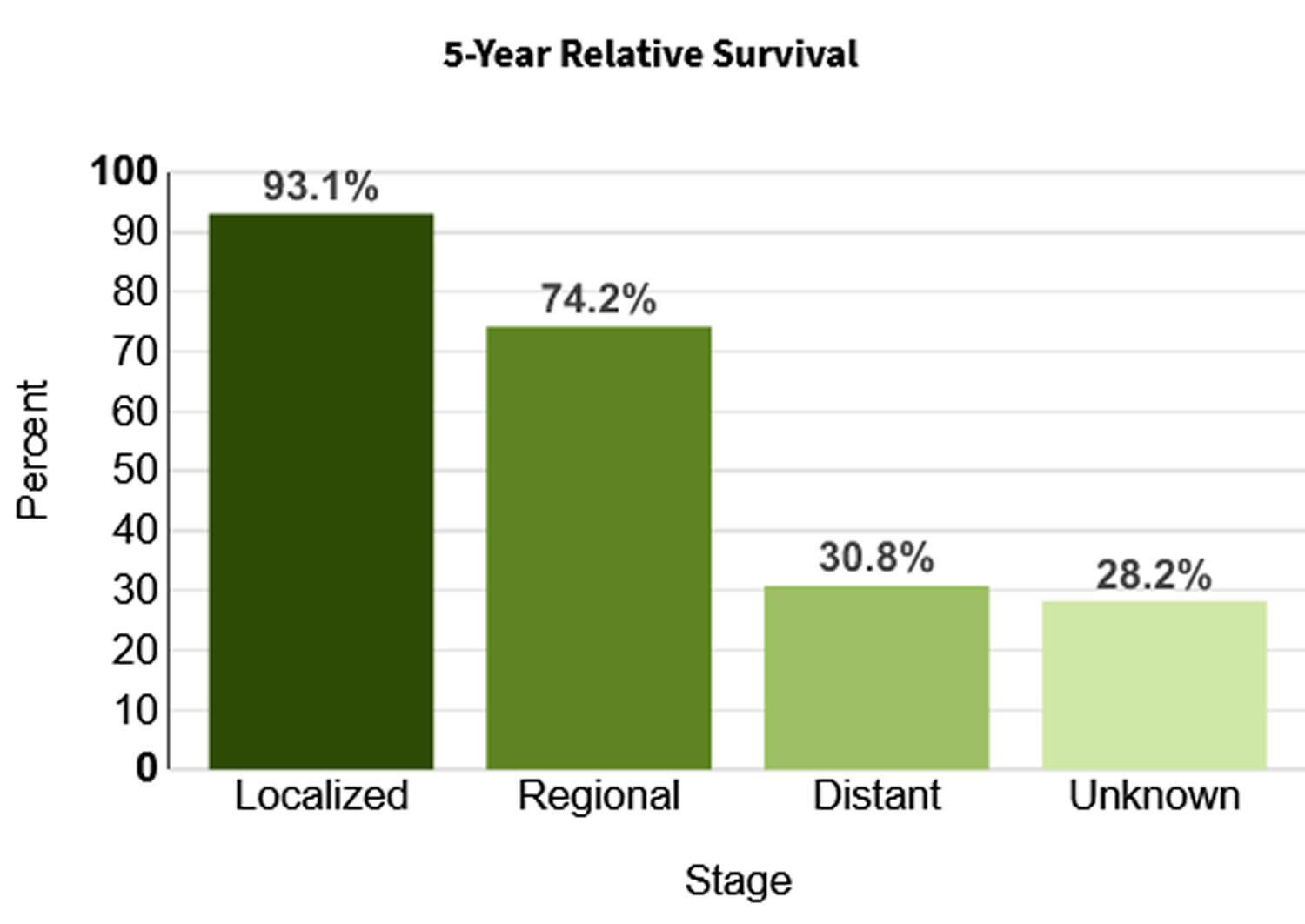

- Ovarian cancer survival rate

- Endometriosis

- Pelvic inflammatory disease

- How common is pelvic inflammatory disease in the United States?

- Can pelvic inflammatory disease be cured?

- What can happen if pelvic inflammatory disease is not treated?

- Can I get pregnant if I have had pelvic inflammatory disease?

- Who gets pelvic inflammatory disease?

- How do you get pelvic inflammatory disease?

- Can women who have sex with women get pelvic inflammatory disease?

- Pelvic inflammatory disease causes

- Risk factors for developing pelvic inflammatory disease

- Pelvic inflammatory disease prevention

- Pelvic inflammatory disease signs and symptoms

- Pelvic inflammatory disease diagnosis

- Pelvic inflammatory disease treatment

- Ectopic pregnancy

What is ovarian pain?

Ovarian pain also called pelvic pain is a general term to describe pain women feel in their lower abdomen below their belly button or in their pelvis. The pelvic region includes the lower stomach, lower back, buttocks, and genital area 1. Your pelvis contains your ovaries, uterus and fallopian tubes and also include many muscles, joints, and your bowel (intestines) and urine bladder. Ovarian pain can have many causes including ovarian cysts, ovarian cancer, endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease (a sexually transmitted disease [STD] or sexually transmitted infection [STI] caused by bacterial infection that are passed on through sexual contact infecting the female reproductive system that can affect your uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries), ovarian torsion (a medical emergency that occurs when an ovary twists on its supporting ligaments cutting off the blood supply to the ovary, which can cause tissue death if not treated promptly), ectopic pregnancy (when a fertilized egg implants and grows outside the main cavity of your uterus or womb) or other female related health issues. Your current physical factors (such as your physical health conditions, inflammation and your hormones), psychological factors (such as how pain affects your mood and sleep and how you think about your pain) and social factors (such as your relationships, your workplace and your social connections) can all contribute to you developing ovarian pain. In other words, many conditions can cause your ovarian pain or pelvic pain. Some are serious requiring emergency care, while others aren’t a cause for concern. Therefore, you should see your doctor for any ovary or pelvic pain. Moreover, not all causes of ovary pain are serious. In most cases, ovary pain isn’t cancer. Less serious conditions and diseases are more likely to be the cause of ovary pain. In any event, your doctor is the best person to evaluate your symptoms and determine an underlying cause of your ovary pain.

Be sure to get pelvic pain checked by your doctor if it’s new, it disrupts your daily life or it gets worse over time. Because your reproductive health is an important part of your overall physical, mental and emotional health and wellbeing. Having a healthy reproductive system allows you to have a safe and healthy sex life, the choice to have a child if you wish, a healthy pregnancy, and maternity care. Keeping up with your annual health and gynecological exams can be helpful because these visits help your doctor spot potential problems before they become something more serious.

How bad your pain is does not always reflect the seriousness of the condition causing your pain. Women describe pelvic pain in many ways. Ovarian pain may be constant or come and go (recurrent pain). It can be a sharp and stabbing pain felt in a specific spot, or a dull pain that is spread out. Ovarian pain can be short-lived also known as acute pelvic pain. It also may occur over weeks, months or years, also known as chronic pelvic pain or persistent pelvic pain. Ovarian pain can feel like cramping, bloating, or constipation pain in your abdomen. Some women have pain that occurs only during their menstrual periods. Some women feel pain when they need to use the bathroom, and some feel pain when lifting something heavy. Because ovarian pain is non-specific term to describe anything that can cause pelvic pain, you’ll need to see your doctor right away if you have pelvic pain so severe that you can’t move without causing more pain. Also see your doctor if you can’t sit still or find a comfortable position.

Having a healthy reproductive system requires you knowing when to ask for help from your doctor. To help prevent reproductive health problems, it is important to reach out to health services when you need them, including:

- family planning services

- health care, including preventive screening, diagnosis and treatment of reproductive issues, abortion services, and pregnancy and delivery care

- contraception

- prevention and treatment of sexually transmissible infection (STI) or sexually transmitted disease (STD)

- health care and support in cases of family, domestic and sexual violence.

To diagnose your pain, your doctor will ask you about your symptoms and do a physical examination. Your doctor may recommend having an ultrasound or other imaging scan to look at your pelvic area. Sometimes, your doctor may recommend an operation to check possible causes. A laparoscopy (keyhole surgery) uses a camera to look inside your pelvis, while a cystoscopy uses a small camera to look inside your bladder. You may need to see a gynecologist, pain specialist, physical therapist or a psychologist as part of investigating and treating your pain.

Treatment for pelvic pain is tailored to each patient, depending on the underlying causes of the pain, how bad the pain is, and how often it occurs:

- For ovarian cysts, monitoring is often the first step because many go away on their own.

- For uterine fibroids, over-the-counter medications like ibuprofen or naproxen can help with mild pain.

- Antibiotics if your doctor suspects pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) or a sexually transmitted infection (STI).

- Hormones for conditions such as endometriosis or heavy menstrual bleeding.

- Some people experience pain in the area around their ovaries just before or when they get their period. Like ovulation pain, it’s not a cause for concern. It happens because your uterus is contracting in order to shed your uterine lining. Taking over-the-counter pain relievers or using a heating pad can help.

- Treatment for ovulation pain usually involves over-the-counter (OTC) pain medication like ibuprofen. Some people find relief by taking birth control pills because they prevent ovulation from happening. Luckily, ovulation pain usually lasts just a few days and doesn’t cause any long-term complications.

- Surgery for some women with adhesions, adenomyosis or endometriosis.

- Physical therapy and biofeedback for women with myofascial (connective tissue) or muscle pain.

- Psychological therapy, medication, or both to help you cope with chronic pain. A therapist can offer support and tools to handle living with chronic pain, and can also help you and your partner cope with the relationship and sexual issues that can arise as a result of chronic pain.

- Healthy nutrition such as a diet rich in fruits, vegetables and grains is important for constipation and diverticulitis. Avoiding foods that can increase inflammation and increasing foods that decrease inflammation can be useful.

- For severe pain, seek medical advice.

Figure 1. Gastrointestinal tract (human digestive system)

Figure 2. Pelvic cavity

If you have any persistent ovary or pelvic pain, it’s best to see a doctor right away. Sudden and severe pelvic pain could be a medical emergency. You should also call your local emergency number and ask for an ambulance if you have sudden pelvic pain, you’re unable to stand up straight, nausea, severe vaginal bleeding, and are feeling faint.

See your doctor if you have the following symptoms:

- pain in your lower abdomen, upper thighs or back

- painful, heavy or irregular periods, or no periods at all

- irregular bleeding or bleeding between your periods

- periods that last more than 8 days or are more than 2 to 3 months apart

- pain during or after sex

- infertility

- there’s blood in your urine or poop

- bowel problems (such as constipation, diarrhea)

- bleeding between periods

- bleeding after intercourse

- fever

- bleeding after menopause

- you’re pregnant or have been pregnant in the last six months.

Also see your doctor if there is any change in your menstrual cycle that worries you.

Pelvic pain may be serious if your symptoms develop suddenly or if the discomfort is severe. If you have pelvic pain that lasts for more than two weeks, schedule an appointment with a doctor.

Female reproductive system

The female reproductive system includes parts of the female body that are involved in sexual activity, fertility, pregnancy and childbirth. The female reproductive system is made up of female body parts that include the following:

- Ovaries — There are 2 ovaries, which are about the size and shape of almonds, 1 ovary on each side of the uterus where female hormones (estrogen and progesterone) are produced, and eggs (ova) are stored to mature. Every month, an egg (ovum) is released. This is called ovulation. All the other female reproductive organs are there to transport, nurture and otherwise meet the needs of the egg or developing fetus.

- Fallopian tubes are 2 thin tubes that connect your ovaries to your uterus (womb), allowing the egg (ovum) to travel to your uterus (womb).

- The fallopian tubes are about 10 cm long and begin as funnel-shaped passages next to the ovary. They have a number of finger-like projections known as fimbriae on the end near the ovary. When an egg is released by the ovary it is ‘caught’ by one of the fimbriae and transported along the fallopian tube to the uterus. The egg is moved along the fallopian tube by the wafting action of cilia — hairy projections on the surfaces of cells at the entrance of the fallopian tube — and the contractions made by the tube. It takes the egg about 5 days to reach the uterus and it is on this journey down the fallopian tube that fertilisation may occur if a sperm penetrates and fuses with the egg. The egg, however, is usually viable for only 24 hours after ovulation, so fertilization usually occurs in the top one-third of the fallopian tube.

- Uterus (the womb) — Your uterus also known as the womb is a hollow muscular organ about the size of a pear (in women who have never been pregnant) that exists to house a developing fertilized egg (zygote). The main part of the uterus which sits in the pelvic cavity is called the body of the uterus, while the rounded region above the entrance of the fallopian tubes is the fundus and its narrow outlet, which protrudes into the vagina, is the cervix. The thick wall of your uterus is composed of 3 layers. The inner layer is known as the endometrium. The inner lining of your uterus (endometrium) thickens with blood and other substances every month. If an egg (ovum) has been fertilized (zygote), pregnancy occurs, the fertilized egg (zygote) will burrow into the endometrium in your uterus, where it will stay for the rest of its growth, growing into a fetus and then a baby. Your uterus (womb) will expand during a pregnancy to make room for the growing fetus. A part of the wall of the fertilized egg (zygote), which has burrowed into the endometrium, develops into the placenta. If an egg has not been fertilized, the endometrial lining is shed at the end of each menstrual cycle, this lining flows out of your body. This is known as menstruation or your period.

- The myometrium is the large middle layer of your uterus, which is made up of interlocking groups of muscle. It plays an important role during the birth of a baby, contracting rhythmically to move the baby out of the body via the birth canal (vagina).

- Cervix is the lower part of your uterus, that connects your uterus to your vagina.

- Vagina is a muscular tube connecting your cervix to the outside of your body (the vestibule of the vulva). Your vagina receives the penis and semen during sexual intercourse and also provides a passageway for menstrual blood flow to leave the body.

The female reproductive system also plays an important part in pregnancy and birth.

Figure 3. Female reproductive system (normal female reproductive system anatomy)

Figure 4. Female reproductive system

What are the ovaries?

Ovaries are female reproductive glands found only in females (women). The 2 ovaries (one ovary is on each side of your uterus or womb) produce female hormones (estrogen and progesterone) and eggs (ova) for reproduction. The eggs travel from your ovaries through the fallopian tubes into your uterus (womb) where the fertilized egg settles in and develops into a fetus (unborn baby).

Your ovaries are held in place by various ligaments which anchor them to your uterus and the pelvis. The ovary contains ovarian follicles, in which eggs develop. Once a follicle is mature, it ruptures and the developing egg is ejected from the ovary into the fallopian tubes. This is called ovulation. Ovulation occurs in the middle of the menstrual cycle and usually takes place every 28 days or so in a mature female. It takes place from either the right or left ovary at random.

Your ovaries are mainly made up of 3 kinds of cells. Each type of cell can develop into a different type of tumor:

- Epithelial tumors start from the cells that cover the outer surface of the ovary. Most ovarian tumors are epithelial cell tumors.

- Germ cell tumors start from the cells that produce the eggs (ova).

- Stromal tumors start from structural tissue cells that hold the ovary together and produce the female hormones estrogen and progesterone.

Some of these tumors are benign (non-cancerous) and never spread beyond the ovary. Malignant (cancerous) or borderline (low malignant potential) ovarian tumors can spread (metastasize) to other parts of the body and can be fatal.

Figure 5. The ovaries lie in shallow depressions in the lateral wall of the pelvic cavity

Figure 6. Ovary anatomy

Figure 7. Normal ovary

Figure 8. Ovary blood supply

What is menstruation and the menstrual cycle?

Each menstrual cycle prepares you for a possible pregnancy. The lining of your uterus thickens and once a month during ovulation, an egg releases from one of your ovaries to the endometrium (internal lining of the uterus).

During sex, the egg can be fertilized when sperm travels to the uterus. If a sperm fertilises an egg, the endometrium will thicken and grow to support the pregnancy.

If the egg isn’t fertilized, the lining which is mostly blood, breaks down from the uterus and leaves the body from the vagina as a period also known as menstruation, menses or the menstrual flow.

Menopause is when you stop having your period. This usually happens between the ages of 45 and 55 years. The average age of menopause in Western countries is 51 to 52 year of age. At menopause, your ovaries stop making hormones and eggs are no longer ripened or released.

Ovarian pain causes

Many types of diseases and health conditions that can cause pelvic pain and it may be difficult to figure out the specific cause or causes 2. Pelvic pain can start in your digestive, reproductive or urinary systems. Some pelvic pain also can come from certain muscles or ligaments within your pelvis, for example, pulling a muscle in your hip or your pelvic floor. Pelvic pain also might be caused by irritation of nerves in your pelvis. A woman’s pelvic pain may result from multiple causes occurring all at the same time 3. In many cases, pelvic pain indicates a problem with one or more of the organs in the pelvic area, such as the uterus, vagina, intestine, or bladder.

Pelvic pain might be caused by problems linked with organs in the female reproductive system. These problems include:

- Adenomyosis — when tissue that lines the inside of the uterus grows into the wall of the uterus.

- Endometriosis — when tissue that’s similar to the tissue that lines your uterus grows outside your uterus such as your fallopian tubes or ovaries. Endometriosis can cause symptoms like severe pain and cramping in your ovaries. Untreated endometriosis can make it difficult for you to get pregnant. Your doctor may perform a pelvic ultrasound, MRI or laparoscopy to get a better look at your pelvic region. There isn’t one treatment for endometriosis. Hormonal medications like birth control can help with pain and bleeding. Surgery to remove scarring from endometriosis can also help with painful symptoms.

- Ovarian tumors are solid masses that grow in your ovary. They can be cancerous or noncancerous. Ovarian germ cell tumors and granulosa cell tumors are examples of tumors that can cause painful ovaries. Some examples of noncancerous tumors include a dermoid tumor or teratoma. Doctors diagnose ovarian tumors with ultrasound and imaging tests like computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Treatment for ovarian tumors usually involves surgery to remove the tumors.

- Ovarian cancer is cancer that starts in your ovaries. There are several types of ovarian cancer, and the treatment and outlook (prognosis) for each are different. Symptoms of ovarian cancer also vary. Cancer in your ovaries can cause ovary pain that’s severe or different from typical menstrual cycle pain. You may also feel bloated or full. It’s important to catch cancer early and begin treatment as soon as possible. Remember, ovary pain is rarely cancer, but you should see your doctor just in case. Your doctor may recommend a blood test called a CA-125 test that checks for proteins commonly found in people with ovarian cancer.

- Ovarian cysts are fluid-filled sacs that form in or on your ovaries and are usually noncancerous. However, ovarian cysts can cause unpleasant symptoms, like pain in your ovaries, pain during sex and irregular menstrual bleeding. Ovarian cysts can rupture (burst) and cause internal bleeding and severe abdominal pain. Your doctor can diagnose ovarian cysts with a pelvic exam and ultrasound. A lot of ovarian cysts go away on their own or with the help of hormonal birth control pills. If you need surgery, your doctor can remove an ovarian cyst with a minimally invasive procedure called laparoscopy. This involves removing the cyst through a small incision.

- Ovarian torsion is when your ovary twists around the ligaments that hold it in place. It most often occurs due to a cyst, tumor or from polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). You’re also at higher risk for ovarian torsion if you’re undergoing fertility treatments to get pregnant. Ovarian torsion can cause severe and sudden pain in your ovaries and pelvis. It’s a medical emergency and requires surgery to untwist your ovary.

- Ovarian remnant syndrome (ORS) occurs when ovarian tissue is left over from surgery to remove your ovaries (oophorectomy) and fallopian tubes (salpingectomy). This tissue can cause pelvic pain, pain during sex or problems when you urinate or poop.

- Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is an infection of the female reproductive organs. Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) affects the organs in your pelvis, including your ovaries. Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) can lead to permanent damage and affect your ability to get pregnant. Symptoms of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) are similar to other conditions involving your reproductive organs, such as pain in your abdomen, painful sex and irregular bleeding. Doctors diagnose pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) through a pelvic exam and other tests that check your vaginal fluid for infection (including sexually transmitted infections, or STIs). Antibiotics treat pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). Because it can cause long-term complications, getting prompt treatment for pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is important.

- Uterine fibroids are noncancerous growths that develop within the muscle lining of your uterus. They can cause pain in your pelvic area, including around your ovaries. Another common symptom of fibroids is heavy or abnormal vaginal bleeding. Doctors treat uterine fibroids with medication or with a surgical procedure called a myomectomy.

- Vulvodynia — chronic pain around the opening of the vagina or the surrounding lips (vulva). The cause of vulvodynia is unknown. It’s thought that the nerves, muscles and tissues in the area are inflamed, so treatment is focused on addressing these factors. Women with vulvodynia may find it painful to insert a tampon, have sexual intercourse or even wear tight pants. Symptoms include burning, stinging, stabbing, irritation and rawness. The pain may be constant or intermittent, localized or diffuse.

Pregnancy complications might lead to pelvic pain, including:

- Ectopic pregnancy — when a fertilized egg grows outside your uterus, usually in your fallopian tubes. It causes severe pain in your ovaries and is a medical emergency. The early symptoms of an ectopic pregnancy can be very similar to typical pregnancy symptoms. Some of these include vaginal bleeding, pain in your abdomen and feeling tired or weak. Doctors usually diagnose ectopic pregnancies in the first trimester (up to 12 weeks of pregnancy) using ultrasound.

- Miscarriage — the loss of a pregnancy before 20 weeks.

- Placental abruption — when the organ that brings oxygen and nutrients to the baby called the placenta separates from the inner wall of the uterus.

- Preterm labor — when the body gets ready to give birth too early.

- Stillbirth — the loss of a pregnancy after 20 weeks.

Pelvic pain also may be caused by symptoms tied to the menstrual cycle, such as:

- Menstrual cramps also called dysmenorrhea, are throbbing or cramping pains in the lower abdomen. Many women have menstrual cramps just before and during their menstrual periods.

- Mittelschmerz is a German word for “middle pain”, which is ovulation pain that occurs midway through your menstrual cycle around the time an ovary releases an egg and about 14 days before your next menstrual period. Ovary pain during ovulation typically feels like a dull ache on just one side of your pelvis. This is because only one ovary releases an egg at a time. Other symptoms of ovulation pain may include vaginal discharge or light bleeding.

Other health conditions may cause pelvic pain. Many of these problems start in or affect your digestive system:

- Appendicitis — is inflammation of the appendix, a small tube in the lower right abdomen. It’s a medical emergency that can lead to serious complications if left untreated.

- Colon cancer — cancer that starts in the part of your large intestine called the colon.

- Constipation — which can be chronic and last for weeks or longer.

- Crohn’s disease — is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) that affects your digestive tract. It can cause inflammation, diarrhea, weight loss, and abdominal pain.

- Diverticulitis — is an inflammation or infection of abnormal pouches in your large intestine. It can cause sudden lower abdominal pain, fever, nausea, vomiting, bloating, and changes in stool.

- Intestinal obstruction — when something blocks food or liquid from moving through the small or large intestine.

- Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) — is a digestive condition that causes abdominal pain and changes in bowel movements. Symptoms include cramping, belly pain, bloating, gas, and diarrhea or constipation, or both. Stress and diet can aggravate the condition. IBS is an ongoing condition that needs long-term management.

- Pelvic adhesions. Adhesions are bands of scar tissue that form between internal tissues and organs binding these organs together. Adhesions can form as a result of previous pelvic or abdominal surgery or previous infections, such as appendicitis or pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) or by endometriosis 2, 4. There is disagreement about whether adhesions can cause pain. It has been proposed that pain may occur when adhesions prevent normal movement of internal organs, such as the bowel (intestine) 5. Symptoms from adhesions include generalized pelvic discomfort or localized pain. Adhesions can be difficult to diagnose, but in some cases the uterus and ovaries feel bound together on pelvic examination. A definitive diagnosis of adhesions is usually made during surgical exploration, frequently via laparoscopy. Surgery to cut bands of scar tissue can relieve pain. However, sometimes the adhesions re-form.

- Ulcerative colitis — is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) that affects your large intestine (colon) and rectum. It can cause ulcers, inflammation, and bleeding.

Some problems in your urinary system may also cause pelvic pain:

- Interstitial cystitis also called painful bladder syndrome, is a chronic bladder condition that causes pain and discomfort in your bladder and sometimes causes pelvic pain. This pain may be a burning or sharp pain in the bladder or at the opening where urine leaves the body (urethra), and it is often relieved by emptying the bladder 6. This and other bladder symptoms, such as the need to urinate frequently or urgently, may need to be evaluated by a urologist.

- Kidney infection — which can affect one or both kidneys.

- Kidney stones also called nephrolithiasis are hard deposits of minerals and salts that form in your kidneys. Kidney stones can cause sharp pain in your side, back, lower abdomen, or groin and blood in your urine.

- Urinary tract infection (UTI) — when any part of your urinary system (the bladder, urethra, and kidneys) gets infected. Symptoms include pain or burning when urinating, frequent urination, and cloudy urine.

Pelvic pain also might be due to other health issues such as:

- Fibromyalgia — a chronic condition that causes widespread pain and tenderness throughout your body. It can also cause fatigue, sleep issues, and cognitive problems.

- Inguinal hernia also known as a groin hernia is a bulge in your groin that occurs when tissue pushes through a weak spot in the abdominal muscles.

- Musculoskeletal causes of pelvic pain are very common but are often overlooked. The muscles, joints and nerves in your pelvis can be injured just like any other part of your body. For instance, tissues can be overstretched, torn or cut in childbirth or surgery; muscles can weaken or tighten from disuse and injury; and habitual postures and movements can slowly stretch or compress structures in the pelvis, leading to pain and dysfunction. The pelvic muscles, joints and nerves may be the sole cause of pain or just a piece of the problem.

- Injury to a nerve in the pelvis that leads to ongoing pain, called pudendal neuralgia. Pudendal neuralgia occurs when the pudendal nerve is injured, irritated, or compressed. Symptoms include burning pain (often unilateral), tingling, or numbness in any of the following areas: buttocks, genitals, or perineum (area between the buttocks and genitals). Symptoms are typically present when a person is sitting but often go away when the person is standing or lying down. The pain tends to increase as the day progresses. Additional symptoms include pain during sex and needing to urinate frequently and/or urgently. Damage to the pudendal nerve can result from surgical procedures, childbirth, trauma, spasms of the pelvic floor muscles, or tumors. Pudendal Neuralgia may also result from certain infections (such as herpes simplex infections) or certain activities (such as cycling and squatting exercises). There are no imaging studies that diagnose Pudendal Neuralgia; however, MRI and CT may help to exclude other causes of the pain.

- Past physical or sexual abuse. If you have been the victim of sexual abuse, you are more likely to experience chronic pelvic pain.

- Pelvic floor muscle spasms. The muscles in your lower back and abdominal wall form the front and back borders of your pelvis, and the pelvic floor muscles around your vagina and rectum, supports the contents of your pelvis. This “sling” of muscles, along with connective tissue called fascia, lift and support the pelvic organs including the bladder, uterus and rectum. Each muscle in your body is surrounded by a strong fibrous tissue called fascia and muscles attach to bones with ligaments. These muscles, fascia, ligaments and bones share some of the same nerves as your pelvic organs. The tension, trigger points, and soft tissue restrictions can cause problems with how these muscles work which can lead to movement dysfunction, pain with movement, pain with intercourse/sex, frequent urination/peeing, problems getting urine stream started (hesitancy), constipation, bloating, and vaginal, rectal, scrotal, and low back pain. Spasms in your pelvic floor muscles — known as pelvic floor tension myalgia or levator ani syndrome — may cause pain locally. Tight bands of muscle, known as trigger points, may be tender to the touch, and they may refer pain to other areas of the pelvis, abdomen and low back. A thorough examination of your abdomen and pelvis can uncover these sources of pain, which can be treated with physical therapy and biofeedback. Some studies show physical therapy helps 60 percent of women with chronic pelvic pain and levator ani syndrome (pelvic floor tension myalgia). Physical therapy helps to align bone or muscular imbalances, decrease abnormal muscle tension and soft tissue, and strengthen your core muscles to prevent further injury. A physical therapist can also help identify other factors that may contribute to your pain, such as poor posture, positioning and habits.

- Physical factors such as your physical health conditions, inflammation and hormones.

- Psychological factors such as how pain affects your mood and sleep and how you think about your pain.

- Social factors such as your relationships, your workplace and your social connections.

Ovarian pain symptoms

Every female experiences ovarian pain differently, especially because ovarian pain can have many different causes. The area you have the pain and the type of pain you feel may not always be the same. Pelvic pain can be severe enough that it interferes with your normal activities, such as going to work, exercising, or having sex. Some women have pain in the vulva (the external genitals), which is called vulvodynia, during sex or when inserting a tampon 4, 7.

Depending on the cause of your ovarian pain or pelvic pain, you may feel:

- dull ache or aching

- sharp pain or stabbing

- burning

- cramping

- pressure or heaviness

- tingling or pins and needles.

You may feel the pain at any time, and it may be triggered at specific times such as:

- during your period

- when you sit on the toilet

- when you sit or stand for a long time

- with certain movements or activities

- during sex

- when you insert a tampon

Your pain may radiate (travel upwards) from your pelvis to your abdomen or down towards your legs.

Ovarian pain diagnosis

When diagnosing the cause of pelvic pain, your doctor will review your symptoms and medical history including your pain history, sexual history and mental health. A physical exam or other tests might also help in determining the cause of pelvic pain.

The physical exam will thoroughly assess the many possible sources of pelvic pain discussed under “causes of pelvic pain” with particular attention to the musculoskeletal system including the back, abdomen and pelvis. A Q-tip test may be performed to test the nerves outside and near the vagina.

If needed, your doctor may order other diagnostic tests such as blood work, urine tests, a pelvic ultrasound or laproscopy.

Some diagnostic tools might include:

- Blood and urine tests.

- Pregnancy tests.

- Vaginal or penile cultures to check for sexually transmitted infections like gonorrhea and chlamydia.

- Abdominal and pelvic X-rays.

- Laparoscopy (a procedure allowing a direct look at the structures in your pelvis and abdomen).

- Hysteroscopy (a procedure to examine your uterus).

- Stool sample to check for signs of blood in your poop.

- Lower endoscopy (insertion of a lighted tube to examine the inside of your rectum and colon).

- Ultrasound (a test that uses sound waves to provide images of internal organs).

- CT scan of your abdomen and pelvis (a scan that uses X-rays and computers to produce cross-sectional images of your body).

You may be referred to a urogynecologist if you have bladder symptoms, or a gastroenterologist if you have gastrointestinal symptoms. If you have a musculoskeletal component to your pelvic pain, your doctor may refer you to a physical therapist for further evaluation and treatment.

Ovarian pain treatment

The treatment of pelvic pain depends on several factors, including the underlying cause, intensity (how bad the pain is) and frequency (how often it occurs) of pain. Common pelvic pain treatments include:

- For ovarian cysts, monitoring is often the first step because many go away on their own.

- For uterine fibroids, over-the-counter medications like ibuprofen or naproxen can help with mild pain.

- Antibiotics if your doctor suspects pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) or a sexually transmitted infection (STI).

- Hormones for conditions such as endometriosis or heavy menstrual bleeding.

- Some people experience pain in the area around their ovaries just before or when they get their period. Like ovulation pain, it’s not a cause for concern. It happens because your uterus is contracting in order to shed your uterine lining. Taking over-the-counter pain relievers or using a heating pad can help.

- Treatment for ovulation pain usually involves over-the-counter (OTC) pain medication like ibuprofen. Some people find relief by taking birth control pills because they prevent ovulation from happening. Luckily, ovulation pain usually lasts just a few days and doesn’t cause any long-term complications.

- Surgery for some women with adhesions, adenomyosis or endometriosis.

- Physical therapy and biofeedback for women with myofascial (connective tissue) or muscle pain.

- Psychological therapy, medication, or both to help you cope with chronic pain. A therapist can offer support and tools to handle living with chronic pain, and can also help you and your partner cope with the relationship and sexual issues that can arise as a result of chronic pain.

- Healthy nutrition such as a diet rich in fruits, vegetables and grains is important for constipation and diverticulitis. Avoiding foods that can increase inflammation and increasing foods that decrease inflammation can be useful.

- For severe pain, seek medical advice.

Ovarian cysts

An ovarian cyst is a fluid-filled sac inside or on the surface of an ovary 8, 9, 10, 11. Most ovarian cysts occur as a normal part of the ovulation process (egg release) of your menstrual cycle, these are called functional ovarian cysts. Functional ovarian cysts usually go away within a few months without any treatment. If you develop an ovarian cyst, your doctor may want to check it again after your next menstrual cycle (period) to see if it has gotten smaller. Other types of ovarian cysts are much less common.

Ovarian cysts can occur at any age but are more common in reproductive years due to endogenous hormone production 12. An ovarian cyst can be more concerning in a female who isn’t ovulating (like a woman after menopause or a girl who hasn’t started her periods), and your doctor may want to do more tests. Your doctor may also order other tests if the ovarian cyst is large or if it does not go away in a few months. Even though most of ovarian cysts are benign (not cancer) and go away on their own without treatment, a small number of them could be cancer 11. Age is the most important independent risk factor, and post-menopausal women with any type of ovarian cyst should have proper follow-up and treatment due to a higher risk for cancer (malignancy) 13, 14. Sometimes the only way to know for sure if the ovarian cyst is cancer is to take it out with surgery. Ovarian cysts that appear to be benign (based on how they look on imaging tests) can be observed (with repeated physical exams and imaging tests), or removed with surgery.

Women have two ovaries — each about the size and shape of an almond — on each side of the uterus. Ovaries are a pair of small organs in the female reproductive system that contain and release an egg once a month in women of menstruating age. This is known as ovulation.

Many women have ovarian cysts at some time and usually form during ovulation. Ovulation happens when the ovary releases an egg each month. Many women with ovarian cysts don’t have symptoms. Most ovarian cysts present little or no discomfort and are harmless 15. The majority disappears without treatment within a few months 8.

Ovarian cysts are common in women with regular periods. In fact, most women make at least one follicle or corpus luteum cyst every month. You may not be aware that you have a cyst unless there is a problem that causes the cyst to grow or if multiple cysts form 16. Ovarian cysts — especially those that have ruptured or twisted— can cause serious symptoms 17, 18, 19. To protect your health, get regular pelvic exams and know the symptoms that can signal a potentially serious problem 19.

About 8% of premenopausal women develop large ovarian cysts that need treatment 20, 21.

Ovarian cysts are less common after menopause. Postmenopausal women with ovarian cysts are at higher risk for ovarian cancer.

At any age, see your doctor if you think you have an ovarian cyst. See your doctor also if you have symptoms such as bloating, needing to urinate more often, pelvic pressure or pain, or abnormal (unusual) vaginal bleeding. These can be signs of an ovarian cyst or other serious problem.

Most ovarian cysts occur naturally and are benign (not cancer) and go away on their own without needing any treatment 11. However, some ovarian cysts can be malignant (cancer), and large cysts greater than 5 cm can increase the risk of ovarian torsion or rupture 16, 22, 23. In these cases, surgical intervention may be indicated to avoid complications 8.

Ovarian cyst key points 24:

- Ovarian cysts are common. Most are variations of normal ovulatory function (functional ovarian cysts). Regardless of age, the likelihood of cancer is significantly less than the likelihood of a benign lesion.

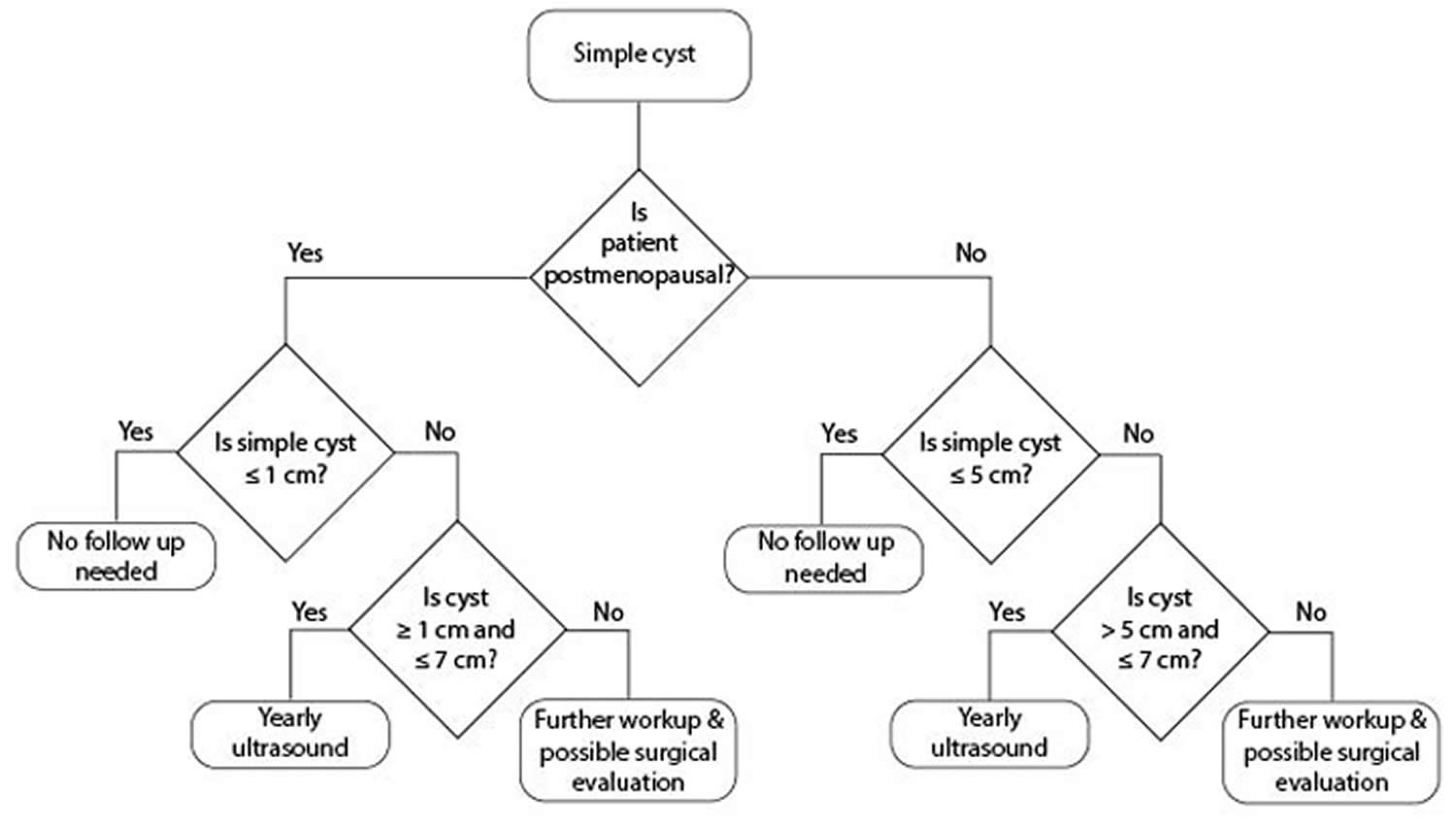

- Patients with ovarian cysts with benign characteristics (round or oval, anechoic, smooth, thin walls, no solid component, no internal flow, no or single thin septation, posterior acoustic enhancement) may be followed by your primary care doctor according to the algorithm in Figures 12 and 13 below, until resolution or stability of the ovarian cyst has been ascertained.

- Women with symptomatic ovarian cysts, those with cysts over 6 cm in diameter, or those with an uncertain, but likely benign diagnosis, can be managed by a general gynecologist.

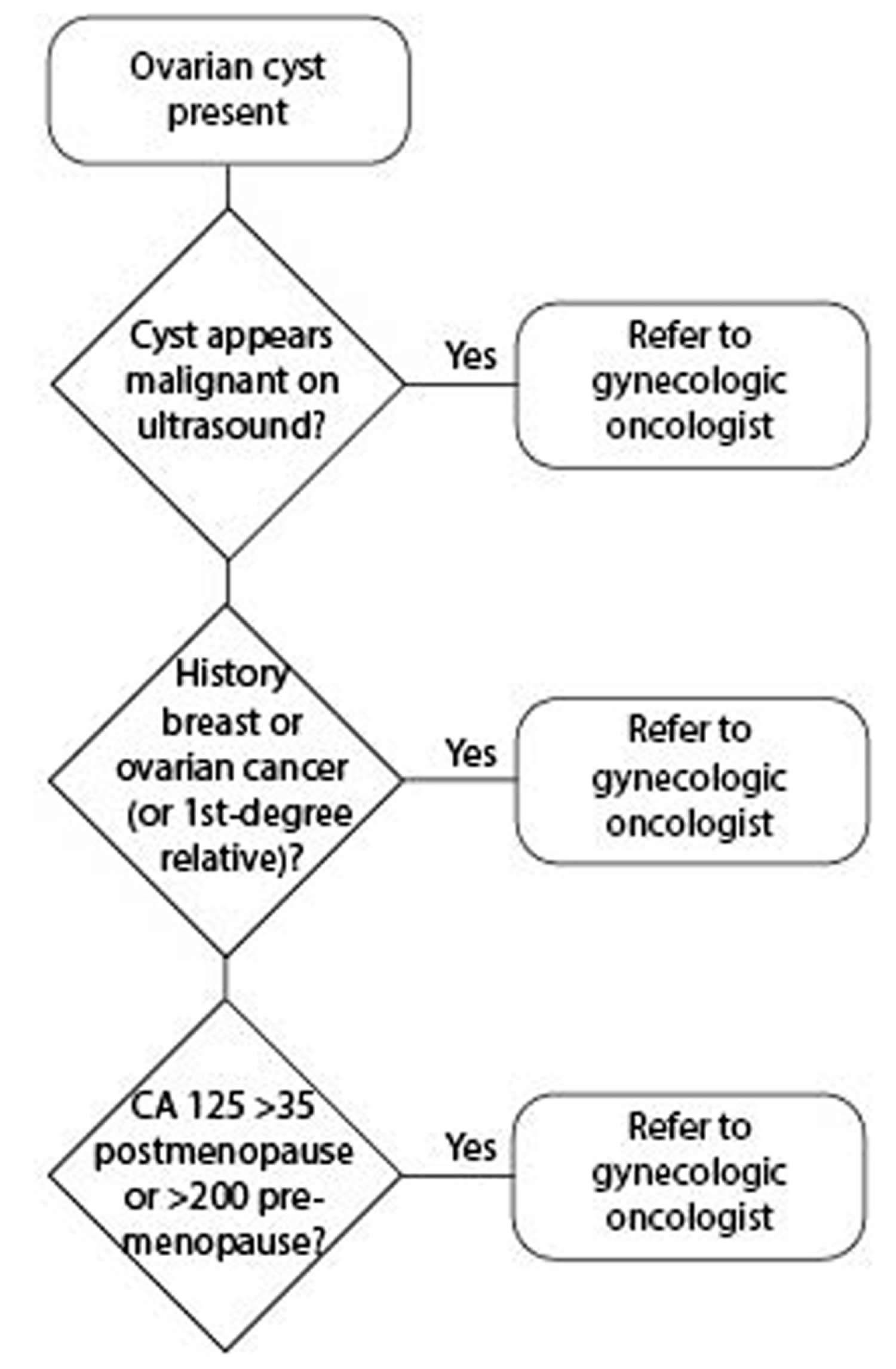

- Patients with ovarian cysts with frankly malignant characteristics (complex structure with thick >3mm septations, nodules or excrescences, especially if multiple or with internal blood flow, solid areas, or ascites) should be referred directly to a gynecologic oncologist. Referral should also be made to gynecologic oncology if the patient has an elevated CA 125 value, a personal or family history of breast or ovarian cancer in a first degree relative, or evidence of metastases.

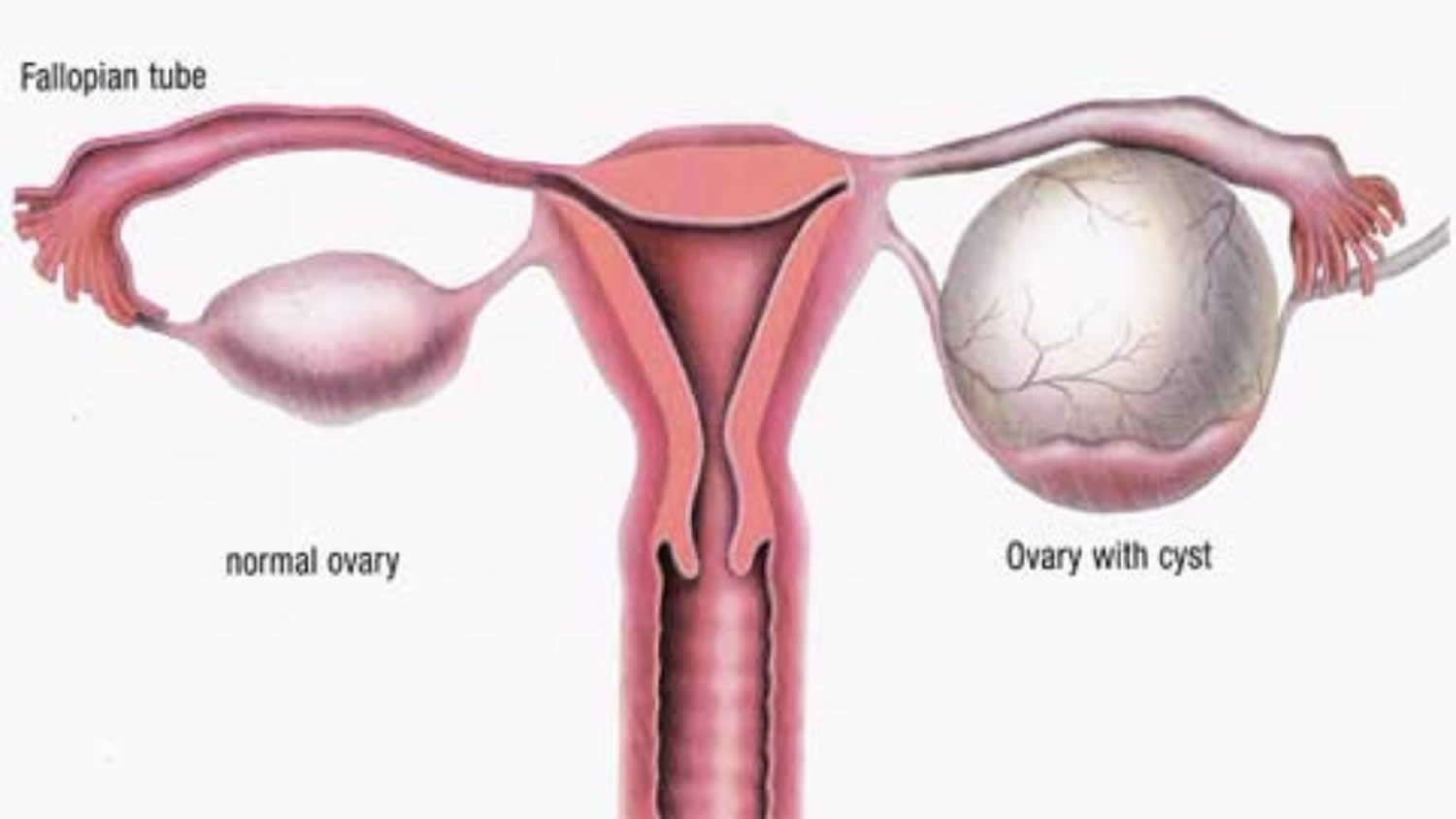

Figure 9. Ovarian cyst

Get immediate medical help if you have:

- Sudden, severe abdominal or pelvic pain.

- Pain with fever or vomiting.

- Signs of shock. These include cold, clammy skin; rapid breathing; and lightheadedness or weakness.

Are ovarian cysts ever an emergency?

Yes, sometimes 15. If your doctor told you that you have an ovarian cyst and you have any of the following symptoms, get medical help right away:

- Pain with fever and vomiting

- Sudden, severe abdominal pain

- Faintness, dizziness, or weakness

- Rapid breathing

These symptoms could mean that your cyst has broken open, or ruptured. Sometimes, large, ruptured cysts can cause heavy bleeding 15.

Can ovarian cysts lead to cancer?

Yes, some ovarian cysts can become cancerous 15. But most ovarian cysts are not cancerous 15.The risk for ovarian cancer increases as you get older. Women who are past menopause with ovarian cysts have a higher risk for ovarian cancer. Talk to your doctor about your risk for ovarian cancer. Screening for ovarian cancer is not recommended for most women 25. This is because testing can lead to “false positives.” A false positive is a test result that says a woman has ovarian cancer when she does not.

Ovarian cancer risk factors

Generally, it’s not possible to say what causes ovarian cancer in an individual woman. However, some features are more common among women who have developed ovarian cancer. These features are called risk factors. Having certain risk factors increases a woman’s chance of developing ovarian cancer.

Having one or more risk factors for ovarian cancer doesn’t mean a woman will definitely develop ovarian cancer. In fact, many women with ovarian cancer have no obvious risk factors.

Factors that increase your risk of ovarian cancers:

- Getting older. The risk of developing ovarian cancer gets higher with age. Ovarian cancer is rare in women younger than 40. Most ovarian cancers develop after menopause. Half of all ovarian cancers are found in women 63 years of age or older.

- Being overweight or obese. Obesity has been linked to a higher risk of developing many cancers. The current information available for ovarian cancer risk and obesity is not clear. Obese women (those with a body mass index [BMI] of at least 30) may have a higher risk of developing ovarian cancer, but not necessarily the most aggressive types, such as high grade serous cancers. Obesity may also affect the overall survival of a woman with ovarian cancer.

- Having children later or never having a full-term pregnancy. Women who have their first full-term pregnancy after age 35 or who never carried a pregnancy to term have a higher risk of ovarian cancer.

- Using fertility treatment. Fertility treatment with in vitro fertilization (IVF) seems to increase the risk of the type of ovarian tumors known as “borderline” or “low malignant potential” (LMP tumors). Other studies, however, have not shown an increased risk of invasive ovarian cancer with fertility drugs. If you are taking fertility drugs, you should discuss the potential risks with your doctor.

- Taking hormone therapy after menopause. Women using estrogens after menopause have an increased risk of developing ovarian cancer. The risk seems to be higher in women taking estrogen alone (without progesterone) for many years (at least 5 or 10). The increased risk is less certain for women taking both estrogen and progesterone.

- Having a family history of ovarian cancer, breast cancer, or colorectal cancer. Ovarian cancer can run in families. Your ovarian cancer risk is increased if your mother, sister, or daughter has (or has had) ovarian cancer. The risk also gets higher the more relatives you have with ovarian cancer. Increased risk for ovarian cancer can also come from your father’s side. A family history of some other types of cancer such as colorectal and breast cancer is linked to an increased risk of ovarian cancer. This is because these cancers can be caused by an inherited mutation (change) in certain genes that cause a family cancer syndrome that increases the risk of ovarian cancer.

- Having a family cancer syndrome. Up to 25% of ovarian cancers are a part of family cancer syndromes resulting from inherited changes (mutations) in certain genes.

- Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome. The hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome is caused by inherited mutations in the genes BRCA1 and BRCA2, as well as possibly some other genes that have not yet been found. The hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome is linked to a high risk of breast cancer as well as ovarian, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal cancers. The risk of some other cancers, such as pancreatic cancer and prostate cancer, are also increased. Mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 are also responsible for most inherited ovarian cancers. Mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 are about 10 times more common in those who are Ashkenazi Jewish than those in the general U.S. population. The lifetime ovarian cancer risk for women with a BRCA1 mutation is estimated to be between 35% and 70%. This means that if 100 women had a BRCA1 mutation, between 35 and 70 of them would get ovarian cancer. For women with BRCA2 mutations the risk has been estimated to be between 10% and 30% by age 70. These mutations also increase the risks for primary peritoneal carcinoma and fallopian tube carcinoma. In comparison, the ovarian cancer lifetime risk for the women in the general population is less than 2%.

- PTEN tumor hamartoma syndrome. In this syndrome, also known as Cowden disease, people are primarily affected with thyroid problems, thyroid cancer, and breast cancer. Women also have an increased risk of endometrial and ovarian cancer. It is caused by inherited mutations in the PTEN gene.

- Lynch syndrome, also known as hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC). Women with this syndrome have a very high risk of colon cancer and also have an increased risk of developing cancer of the uterus (endometrial cancer) and ovarian cancer. Many different genes can cause hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC). They include MLH1, MLH3, MSH2, MSH6, TGFBR2, PMS1, and PMS2. The lifetime risk of ovarian cancer in women with hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer (Lynch syndrome) is about 10%. Up to 1% of all ovarian epithelial cancers occur in women with hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer (Lynch syndrome).

- Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. People with this rare genetic syndrome develop polyps in the stomach and intestine while they are teenagers. They also have a high risk of cancer, particularly cancers of the digestive tract (esophagus, stomach, small intestine, colon). Women with this syndrome have an increased risk of ovarian cancer, including both epithelial ovarian cancer and a type of stromal tumor called sex cord tumor with annular tubules (SCTAT). This syndrome is caused by mutations in the gene STK11.

- MUTYH-associated polyposis. People with this syndrome develop polyps in the colon and small intestine and have a high risk of colon cancer. They are also more likely to develop other cancers, including cancers of the ovary and bladder. This syndrome is caused by mutations in the gene MUTYH.

- Having had breast cancer. If you have had breast cancer, you might also have an increased risk of developing ovarian cancer. There are several reasons for this. Some of the reproductive risk factors for ovarian cancer may also affect breast cancer risk. The risk of ovarian cancer after breast cancer is highest in those women with a family history of breast cancer. A strong family history of breast cancer may be caused by an inherited mutation in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes and hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome, which is linked to an increased risk of ovarian cancer.

- Smoking and alcohol use. Smoking doesn’t increase the risk of ovarian cancer overall, but it is linked to an increased risk for the mucinous type. Drinking alcohol is not linked to ovarian cancer risk.

Can ovarian cysts make it harder to get pregnant?

Typically, no 15. Most ovarian cysts do not affect your chances of getting pregnant 15. Sometimes, though, the illness causing the ovarian cyst can make it harder to get pregnant.

Two conditions that cause ovarian cysts and affect fertility are 15:

- Endometriosis, which happens when the lining of the uterus (womb) grows outside of the uterus. Cysts caused by endometriosis are called endometriomas.

- Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), one of the leading causes of infertility (problems getting pregnant). Women with PCOS often have many small cysts on their ovaries.

If you need an operation to remove your cysts, your surgeon will aim to preserve your fertility whenever possible.

This may mean removing just the cyst and leaving the ovaries intact, or only removing 1 ovary.

In some cases, surgery to remove both your ovaries may be necessary, in which case you’ll no longer produce any eggs.

Make sure you talk to your surgeon about the potential effects on your fertility before your operation.

How do ovarian cysts affect pregnancy?

Ovarian cysts are common during pregnancy 15. Typically, these cysts are benign (not cancerous) and harmless 26. Ovarian cysts that continue to grow during pregnancy can rupture or twist or cause problems during childbirth. Your doctor will monitor any ovarian cyst found during pregnancy.

Can you prevent ovarian cysts?

No, you cannot prevent functional ovarian cysts if you are ovulating 15. If you get ovarian cysts often, your doctor may prescribe hormonal birth control to stop you from ovulating. This will help lower your risk of getting new cysts.

Ovarian cyst complications

Some women develop less common types of ovarian cysts that a doctor finds during a pelvic exam. Cystic ovarian masses that develop after menopause might be cancerous (malignant). That’s why it’s important to have regular pelvic exams.

Infrequent complications associated with ovarian cysts include:

- Ovarian torsion. Cysts that enlarge can cause the ovary to move, increasing the chance of painful twisting of your ovary (ovarian torsion). Symptoms can include an abrupt onset of severe pelvic pain, nausea and vomiting. Ovarian torsion can also decrease or stop blood flow to the ovaries.

- Ovarian cyst rupture. All ovarian cyst types can potentially rupture, spilling fluid into the pelvis, which is often painful. An ovarian cyst that ruptures can cause severe pain and internal bleeding. If the contents are from a dermoid or abscess, surgical lavage may be indicated. The larger the cyst, the greater the risk of rupture. Vigorous activity that affects the pelvis, such as vaginal intercourse, also increases the risk.

- Bleeding into the ovarian cyst. In the case of hemorrhagic ovarian cysts, the management of hemorrhage depends on the hemodynamic stability of the patient, but is most often expectantly managed.

The fifth most common gynecological emergency is ovarian torsion, defined as the complete or partial twisting of the ovarian vessels resulting in obstruction of blood flow to the ovary. The diagnosis is made clinically with the assistance of a history and physical examination, bloodwork, and imaging and is confirmed by diagnostic laparoscopy. The latest evidence supports a conservative approach during diagnostic laparoscopy, and detorsion of the ovary with or without cystectomy is recommended to preserve fertility.

Ovarian cysts can also rupture or hemorrhage, with most of these being physiological. Most cases are uncomplicated with mild to moderate symptoms, and those with stable vital signs can be managed expectantly. Occasionally, this can be complicated by significant blood loss resulting in hemodynamic instability requiring admission to the hospital, surgical evacuation, and blood transfusion 16.

Ruptured ovarian cyst

Ruptured ovarian cysts and hemorrhagic ovarian cysts are the most common causes of acute pelvic pain in an afebrile, premenopausal woman presenting to the emergency room 27. Rebound tenderness from the pain is possible and the bleeding from a cyst can rarely be severe enough to cause shock 28. It is a common cause of physiological pelvic intraperitoneal fluid.

Ovarian cysts may rupture during pregnancy (if a very early pregnancy, this may cause diagnostic confusion with ectopic pregnancy).

Although rupture of an ovarian follicle is a physiologic event (mittelschmerz (German for ‘middle pain’)), the rupture of an ovarian cyst (>3 cm) may cause more dramatic clinical symptoms.

The sonographic appearance depends on whether a simple or hemorrhagic ovarian cyst ruptures, and whether the cyst has completely collapsed. The most important differential consideration is a ruptured ectopic pregnancy 29.

Ruptured ovarian cyst symptoms

Ruptured ovarian cysts and hemorrhagic ovarian cysts are the most common causes of acute pelvic pain in an afebrile, premenopausal woman presenting to the emergency room 27. The pain from a ruptured ovarian cyst may come from stretching the capsule of the ovary, torquing of the ovarian pedicle, or leakage of cyst contents (serous fluid/blood) which can cause peritoneal irritation 28.

Ruptured ovarian cyst treatment

Ruptured ovarian cyst is treated conservatively in a premenopausal woman unless evidence of hypovolemic shock (tachycardia and postural drop in blood pressure) 29.

A ruptured hemorrhagic cyst in a perimenopausal woman should be viewed more suspiciously and followed up appropriately 29. A hemorrhagic cyst or ruptured cyst in a postmenopausal woman deserves surgical evaluation 29.

Ovarian torsion

Ovarian torsion is caused by twisting of the ligaments that support the ovary, cutting off the blood flow to the ovary and represents a true surgical emergency that can lead to necrosis, loss of ovary, and infertility if not identified early 30, 31. Ovarian torsion is characterized by a twisted ovary with or without the involvement of the fallopian tube 32. When fallopian tube also twists with the ovary it is known as adnexal torsion 33. The diagnosis of ovarian torsion can only be confirmed by surgery 32. Furthermore, the female reproductive function may be negatively affected by delayed treatment because of uncertainty in the preoperative diagnosis.

The ovary has dual blood supply from the ovarian arteries and uterine arteries. The ovary is supported by multiple structures in the pelvis. One ligament it is suspended by is the infundibulopelvic ligament, also called the suspensory ligament of the ovary, which connects the ovary to the pelvic sidewall. This ligament also contains the main ovarian vessels. The ovary is also connected to the uterus by the utero-ovarian ligament 34. Twisting of these ligaments can lead to venous congestion, edema, compression of arteries, and, eventually, loss of blood supply to the ovary. This can cause a constellation of symptoms, including severe pain when blood supply is compromised.

The main risk factor for ovarian torsion is an ovarian mass that is 5 cm in diameter or larger 30. The mass increases the chance that the ovary could rotate on the axis of the two ligaments holding it in suspension. This torsion impedes venous outflow and eventually, arterial inflow.

In a study of torsions confirmed by surgery, 46% were associated with tumors, and 48% were associated with cysts. Of these masses, 89% were benign, and 80% of patients were under age 50. Therefore, reproductive-age females are at greatest risk of torsion 35. However, torsion can still occur in normal ovaries, especially in children and adolescents. Pregnancy, as well as patients undergoing fertility treatments, are high risk due to enlarged follicles on the ovary 34.

The clinical symptoms of ovarian torsion are variable and nonspecific 32. Classic clinical symptoms of ovarian torsion include the sudden onset of severe pelvic pain and a palpable adnexal mass (a lump in tissue near the uterus, usually in the ovary or fallopian tube) 36. Moreover, nausea, vomiting, and fever are present in some cases 37. Reproductive age is the peak period of incidence of ovarian torsion, and approximately 70% of cases occur during this period 38. It is estimated that 12% to 18% of patients with ovarian torsion are pregnant 39, 40, 41. However, whether pregnancy is a risk factor of ovarian torsion is still controversial 42, 43.

Physical exam in the patient is variable. The patient may have abdominal tenderness focally in the lower abdomen, pelvic area, diffusely, or not at all. Up to one-third of patients were found to have no abdominal tenderness. There could also be an abdominal mass. If the patient has guarding, rigidity, or rebound, there may already be necrosis of the ovary. Every patient should also have a pelvic exam to better evaluate for masses, discharge, and cervical motion tenderness.

Pelvic ultrasonic examination is the most frequently performed preoperative examination, but ultrasonic findings are nonspecific, despite the ultrasonic features of ovarian torsion being well-characterized 31, 44, 45.

Ovarian torsion is the fifth most common gynecological emergency requiring surgery, with an estimated prevalence of about 2.7% to 3% 46. Urgent surgery is required to prevent ovarian necrosis. Most ovaries are not salvageable, in which case a salpingo-oophorectomy is required. If not removed, the necrotic ovary can become infected and cause an abscess or peritonitis. In the case of a non-infarcted adnexa, surgical untwisting can be performed. Mortality resulting from ovarian torsion is rare. Spontaneous detorsion has also been reported.

Ovarian torsion symptoms

The clinical symptoms of ovarian torsion are variable and nonspecific 32. Most patients will present with lower abdominal pain or pelvic pain. Pain can be sharp, dull, constant, or intermittent. Pain may radiate to the abdomen, back, or flank 47. One study showed that post-menopausal women commonly presented with dull, constant pain when compared to premenopausal, who more commonly had sharp stabbing pain. Symptoms may or may not be intermittent if the ovary is torsing and detorsing.

The patient may also have associated nausea and vomiting. In one study of children and adolescents with lower abdominal pain, vomiting was found to be an independent risk factor for ovarian torsion 48. The patient may or may not already have a known ovarian mass, which predisposes them to torsion.

Fever may be present if the ovary is already necrotic. The patient could also have abnormal vaginal bleeding, or discharge if torsion involves a tubo-ovarian abscess. Infants with ovarian torsion may present with feeding intolerance or inconsolability.

Ovarian torsion treatment

Ovarian torsion requires urgent surgery to prevent ovarian necrosis 30. The treatment of ovarian torsion is surgical detorsion, preferably by a gynecologist 30.

In reproductive age females, salvage of the ovary should be attempted, and the surgeon must evaluate the ovary for viability 30. Most often, the approach to surgery should be laparoscopic and involves direct visualization of a twisted ovary. The evaluation of viability is mostly by visualization. A dark, enlarged ovary with hemorrhagic lesions may have compromised blood flow but is often salvageable 40.

After detorsion, ovaries were found to be functional in greater than 90% of patients who underwent detorsion 30. This was assessed by the appearance of the adnexa on ultrasound, including follicular development on the ovaries 49. Therefore, surgery with sparing of the ovary is the management of choice 30. Rarely, if the ovary appears necrotic and gelatinous beyond possible salvage, the surgeon may choose to perform a salpingo-oophorectomy 30. The surgeon may also perform cystectomy if a benign ovarian cyst is present. If the ovarian cyst appears to be malignant, or if the woman is post-menopausal, salpingo-oophorectomy is the preferred management 30.

Ovarian torsion prognosis

Ovarian torsion is not usually life-threatening, but it is organ threatening. In premenopausal women, surgery with sparing of the ovary is now the preferred treatment, and the majority of women had normal-appearing ovary on ultrasound after surgery 50. Ovarian salvage is increased in patients with less time from the onset of symptoms to surgical intervention. In postmenopausal women, salpingo-oophorectomy is done to prevent reoccurrence. This approach is also used in women with a mass suspicious for malignancy. The majority of ovarian masses are benign. Some case reports show less than 2% of torsions involving a malignant lesion. However, the chances of a malignant lesion involved in ovarian torsion are increased in the postmenopausal women 34.

The main complication of ovarian torsion is the inability to salvage the ovary and the need for salpingo-oophorectomy. This may affect fertility in a woman of childbearing age. Other complications of ovarian torsion include abnormal pelvic anatomy that may contribute to infertility, such as adhesions, or atrophied ovaries 51. There may be complications from the surgery itself, such as infection or venous thromboembolism. The risk of post-operative infection is increased when necrotic tissue is already present 52.

Ovarian cyst types

The most common types of ovarian cysts are called functional cysts, they form during the menstrual cycle and they happen if you have not been through the menopause (see Figure 4. Normal ovary) 53, 15. Functional ovarian cysts are usually benign (not cancerous) 15. Functional ovarian cysts are usually harmless, rarely cause pain, and often disappear on their own within two or three menstrual cycles.

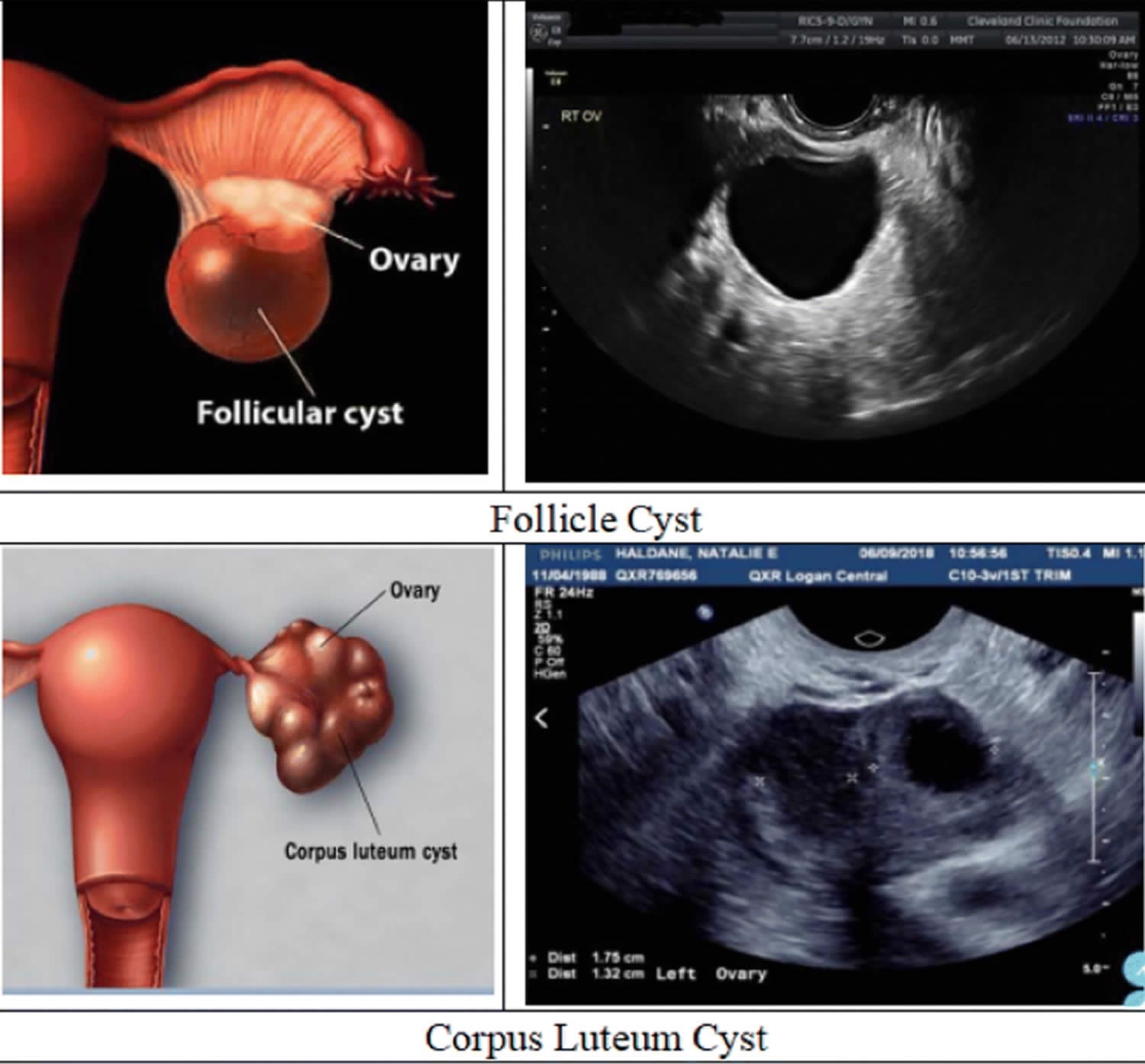

The two most common types of functional cysts are 15:

- Follicle cysts. In a normal menstrual cycle, an ovary releases an egg each month. The egg grows inside a tiny sac called a follicle. When the egg matures, the follicle breaks open to release the egg. Around the midpoint of your menstrual cycle, an egg bursts out of its follicle and travels down the fallopian tube. Follicle cysts form when the follicle doesn’t break open to release the egg. This causes the follicle to continue growing into a cyst. Follicular cysts can appear smooth, thin-walled, and unilocular. Follicle cysts may form because of a lack of physiological release of the egg due to excessive follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) stimulation or the absence of the usual luteinizing hormone (LH) surge at mid-cycle just before ovulation. These cysts continue to grow because of hormonal stimulation. Follicular cysts are usually larger than 2.5 cm in diameter. Follicle cysts often have no symptoms and go away in one to three months.

- Corpus luteum cysts. Once the follicle breaks open and releases the egg, the empty follicle sac shrinks into a mass of cells called corpus luteum. Corpus luteum makes hormones estrogen and progesterone to prepare for the next egg for the next menstrual cycle. Without pregnancy, the life span of the corpus luteum is 14 days. Corpus luteum cysts form if the sac doesn’t shrink. Instead, the sac reseals itself after the egg is released, and then fluid builds up inside. Most corpus luteum cysts go away after a few weeks. But, they can grow to almost four inches wide. They also may bleed or twist the ovary and cause pain. Some medicines used to cause ovulation can raise the risk of getting these cysts. Corpus luteal cysts can appear complex or simple, thick-walled, or contain internal debris. Corpus luteum cysts are always present during pregnancy and usually resolve by the end of the first trimester.

Both follicular and corpus luteal cysts can turn into hemorrhagic cysts. They are generally asymptomatic and spontaneously resolve without treatment 54.

Other types of benign ovarian cysts are less common:

- Theca lutein cysts. Theca lutein cysts are luteinized follicle cysts that form as a result of overstimulation in elevated human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) levels. Theca lutein cysts can occur in pregnant women, women with gestational trophoblastic disease, multiple gestation, and ovarian hyperstimulation.

- Endometriomas are caused by endometriosis. Endometriosis happens when the lining of the uterus (womb) grows outside of the uterus. Some of the lining of the uterus tissue can attach to your ovary and form a growth. Endometriomas (common in endometriosis) arise from ectopic growth of endometrial tissue and are often referred to as chocolate cysts because they contain dark, thick, gelatinous aged blood products. They appear as a complex mass on ultrasound and are described as having “ground glass” internal echoes. Endometriomas can be classified into two types. Type 1 endometrioma consists of small primary endometriomas that develop from surface endometrial implants. Type 2 endometrioma arises from functional cysts that have been invaded by ovarian endometriosis or type 1 endometriomas. Although the overall risk of malignant transformation is low, endometriomas increase this risk in women with endometriosis 55, 56, 57.

- Dermoids also called teratomas come from cells present from birth and do not usually cause symptoms. Dermoid cysts (teratomas) can contains different kinds of tissues that make up the body, such as hair, skin or teeth, because they form from embryonic cells. Although mostly benign, dermoid cysts (teratomas) can undergo a malignant transformation in 1 to 2% of cases 58, 59, 60.

- Cystadenomas develop on the surface of an ovary and might be filled with a watery or a mucous material. These tumors can grow very large even though they usually are benign.

- Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a disorder affecting 5 to 10% of women of reproductive age and is one of the primary causes of infertility. It is associated with diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease. Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) appears as enlarged ovaries with multiple small follicular cysts. The ovaries appear enlarged due to excess androgen hormones in the body, which cause the ovaries to form cysts and increase in size 61.

- Pregnancy ovarian cyst. Ovarian cysts in pregnancy are usually benign. Benign cystic teratomas (dermoid cysts) are the most common ovarian tumor during pregnancy, accounting for one-third of all benign ovarian tumors in pregnancy. The second most common benign ovarian cyst is a cystadenoma. In caring for pregnant women with ovarian cysts, a multidisciplinary approach and referral to a perinatologist and gynecologic oncologist is advised.

- Neonates and prepubertal children ovarian cyst. Ovarian cysts in the neonate are exceedingly rare. It is estimated that 5% of all abdominal masses in the first month of life are ovarian cysts. While there are no precise guidelines for the monitoring and management of neonatal ovarian cysts, it is generally agreed that cysts >2 cm are considered pathologic. The majority of neonatal ovarian cysts are benign and self-limiting. Ovarian malignancy becomes more common in the second decade of life than in the neonatal period. In one small study, approximately 33% of adnexal masses were malignant in children >8 years whereas 2.9% of adnexal masses were malignant in children <8 years 62.

Dermoid cysts and cystadenomas can become large, causing the ovary to move out of position. This increases the chance of painful twisting of your ovary, called ovarian torsion. Ovarian torsion may also result in decreasing or stopping blood flow to the ovary.

In some women, the ovaries make many small cysts. This is called polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). PCOS can cause problems with the ovaries and with getting pregnant.

Malignant (cancerous) ovarian cysts are rare 15. They are more common in older women. Cancerous cysts are ovarian cancer. For this reason, ovarian cysts should be checked by your doctor. Most ovarian cysts are not cancerous.

Ovarian cyst causes

The most common causes of ovarian cysts include 15:

- Hormonal problems. Functional cysts usually go away on their own without treatment. They may be caused by hormonal problems or by drugs used to help you ovulate.

- Endometriosis. Women with endometriosis can develop a type of ovarian cyst called an endometrioma. The endometriosis tissue may attach to the ovary and form a growth. These cysts can be painful during sex and during your period.

- Pregnancy. An ovarian cyst normally develops in early pregnancy to help support the pregnancy until the placenta forms. Sometimes, the cyst stays on the ovary until later in the pregnancy and may need to be removed.

- Severe pelvic infections. Infections can spread to the ovaries and fallopian tubes and cause cysts to form.

- A previous ovarian cyst. If you’ve had one, you’re likely to develop more.

Risk factors of developing ovarian cyst

Risk factors for ovarian cyst formation include:

- Infertility treatment. Patients treated with gonadotropins or other ovulation induction agents, for example clomiphene or letrozole (Femara), may develop ovarian cysts as part of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome 63

- Pregnancy. Sometimes, the follicle that forms when you ovulate stays on your ovary throughout pregnancy. In pregnancy, ovarian cysts may form in the second trimester when hCG levels peak 64. It can sometimes grow larger.

- Endometriosis. Some of the tissue can attach to your ovary and form a cyst.

- Severe pelvic infection. If the infection spreads to the ovaries, it can cause cysts.

- Previous ovarian cysts. If you’ve had one ovarian cyst, you’re likely to develop more.

- Tamoxifen therapy 12. Tamoxifen is widely used as hormonal therapy in both, pre- and postmenopausal women with breast cancer and effectively reduces the risk of recurrence and mortality 65, 66.

- Underactive thyroid (hypothyroidism) 67

- Maternal gonadotropins. The transplacental effects of maternal gonadotropins may lead to the development of fetal ovarian cysts 68.

- Cigarette smoking 69.

- Tubal ligation. Functional ovarian cysts have been associated with tubal ligation sterilizations 70.

Ovarian cyst prevention

Oral contraceptives may prevent new functional cysts from forming 71, 72. However, oral contraceptives do not hasten the resolution of preexisting ovarian cysts. Some doctors will, nevertheless, prescribe oral contraceptives in an attempt to prevent new cysts from confusing the picture. Oral contraceptives are also protective against ovarian cancer 73.

In addition, getting regular pelvic exams ensure that changes in your ovaries are diagnosed as early as possible. Be alert to changes in your monthly cycle. Make a note of unusual menstrual symptoms, especially ones that go on for more than a few cycles. Talk to your doctor about changes that concern you.

Bilateral oophorectomy (surgical removal of both ovaries) protects against ovarian and breast cancer but is associated with an increase in the all-cause mortality rate 74. Current research suggests that removal of the fallopian tubes is protective against ovarian cancer 75.

Early-stage ovarian cancer rarely causes any symptoms or the symptoms can be very vague. Advanced-stage ovarian cancer may cause few and nonspecific symptoms that are often mistaken for more common benign conditions.

Signs and symptoms of ovarian cancer may include roughly 12 or more times a month of having:

- Abdominal bloating or swelling

- Pain or tenderness in your abdomen or the area between the hips (pelvis)

- No appetite or feeling full quickly after eating

- An urgent need to urinate or needing to urinate more often

These symptoms are also commonly caused by benign (non-cancerous) diseases and by cancers of other organs. When they are caused by ovarian cancer, they tend to be persistent and a change from normal − for example, they occur more often or are more severe. These symptoms are more likely to be caused by other conditions, and most of them occur just about as often in women who don’t have ovarian cancer. But if you have these symptoms more than 12 times a month, see your doctor so the problem can be found and treated if necessary.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends that if you (especially if 50 or over) have the following symptoms on a persistent or frequent basis – particularly more than 12 times per month, your doctor should arrange tests – especially if you’re are over 50 76:

- persistent swollen tummy (abdomen) or bloating

- feeling full (early satiety) and/or loss of appetite

- pelvic or abdominal pain

- increased urinary urgency and/or frequency.

First tests:

- Measure serum cancer antigen 125 (CA125) in primary care in women with symptoms that suggest ovarian cancer

- If serum CA125 is 35 IU/ml or greater, arrange an ultrasound scan of the abdomen and pelvis.

- For any woman who has normal serum CA125 (less than 35 IU/ml), or CA125 of 35 IU/ml or greater but a normal ultrasound:

- assess her carefully for other clinical causes of her symptoms and investigate if appropriate

- if no other clinical cause is apparent, advise her to return to her doctor if her symptoms become more frequent and/or persistent.

Ovarian cyst symptoms

Most ovarian cysts are small and don’t cause symptoms. Many ovarian cysts are found during a routine pelvic exam or imaging test done for another reason. Some ovarian cysts may cause a dull or sharp ache in the abdomen and pain during certain activities. Larger ovarian cysts may cause twisting of the ovary. This twisting may cause pain on one side that comes and goes or can start suddenly. Cysts that bleed or burst also may cause sudden, severe pain.

If an ovarian cyst does cause symptoms, you may have pressure, bloating, swelling, or pain in the lower abdomen on the side of the cyst 15. This pain may be sharp or dull and may come and go 15.

If an ovarian cyst ruptures, it can cause sudden, severe pain 15.

If an ovarian cyst causes twisting of an ovary, you may have pain along with nausea and vomiting 15.

Less common symptoms include:

- Pelvic pain that may come and go. You may feel a dull ache or a sharp pain in the area below your bellybutton toward one side.

- Dull ache in the lower back and thighs

- Fullness, pressure or heaviness in your belly (abdomen)

- Feeling very full after only eating a little

- Bloating and a swollen tummy

- Problems emptying your bladder or bowel completely

- Pain during sex

- Unexplained weight gain

- Pain during your period

- Unusual (not normal) vaginal bleeding

- Heavy periods, irregular periods or lighter periods than normal

- Breast tenderness

- Needing to urinate more often

- Difficulty getting pregnant – although fertility is usually unaffected by ovarian cysts.

Ovarian cyst diagnosis

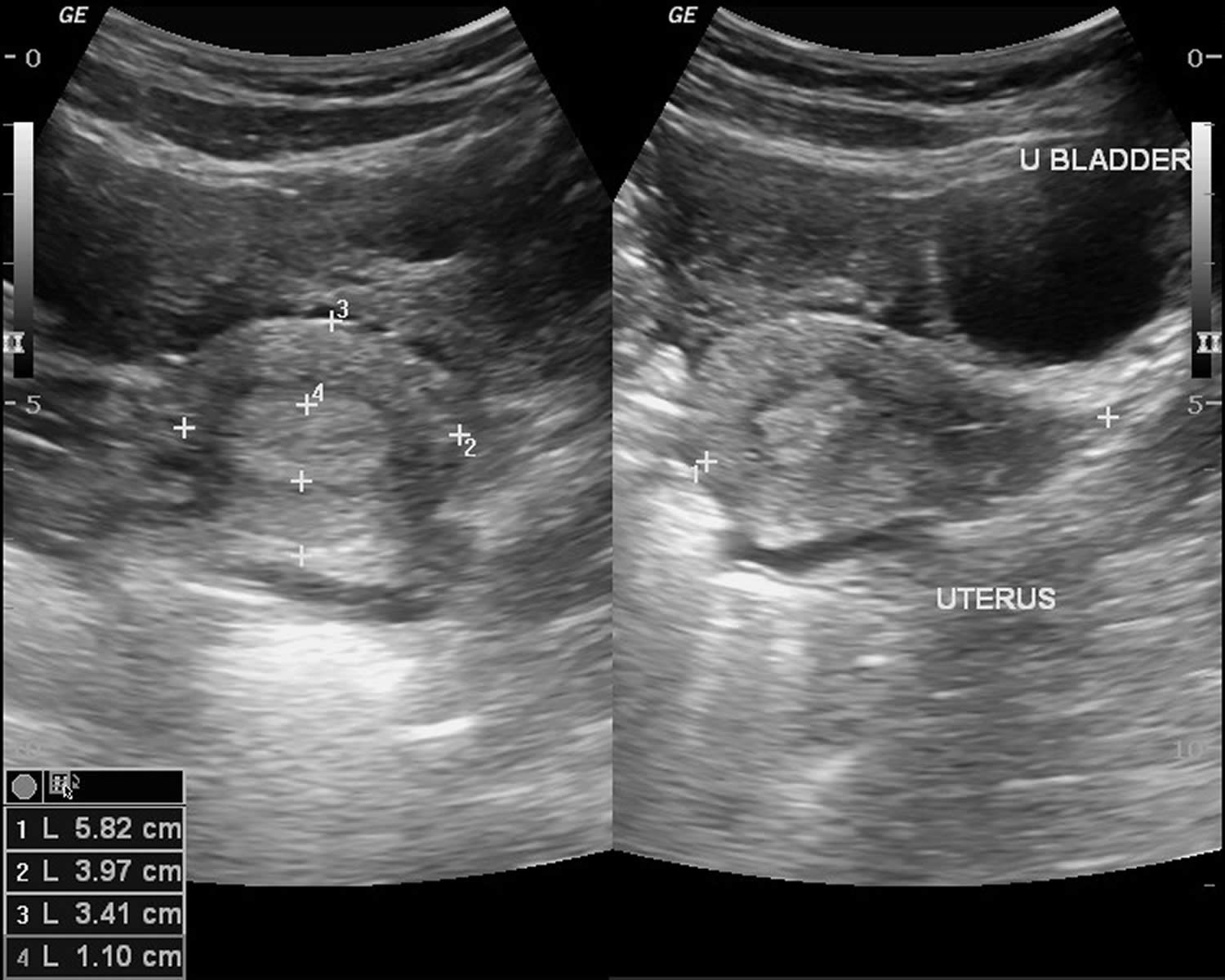

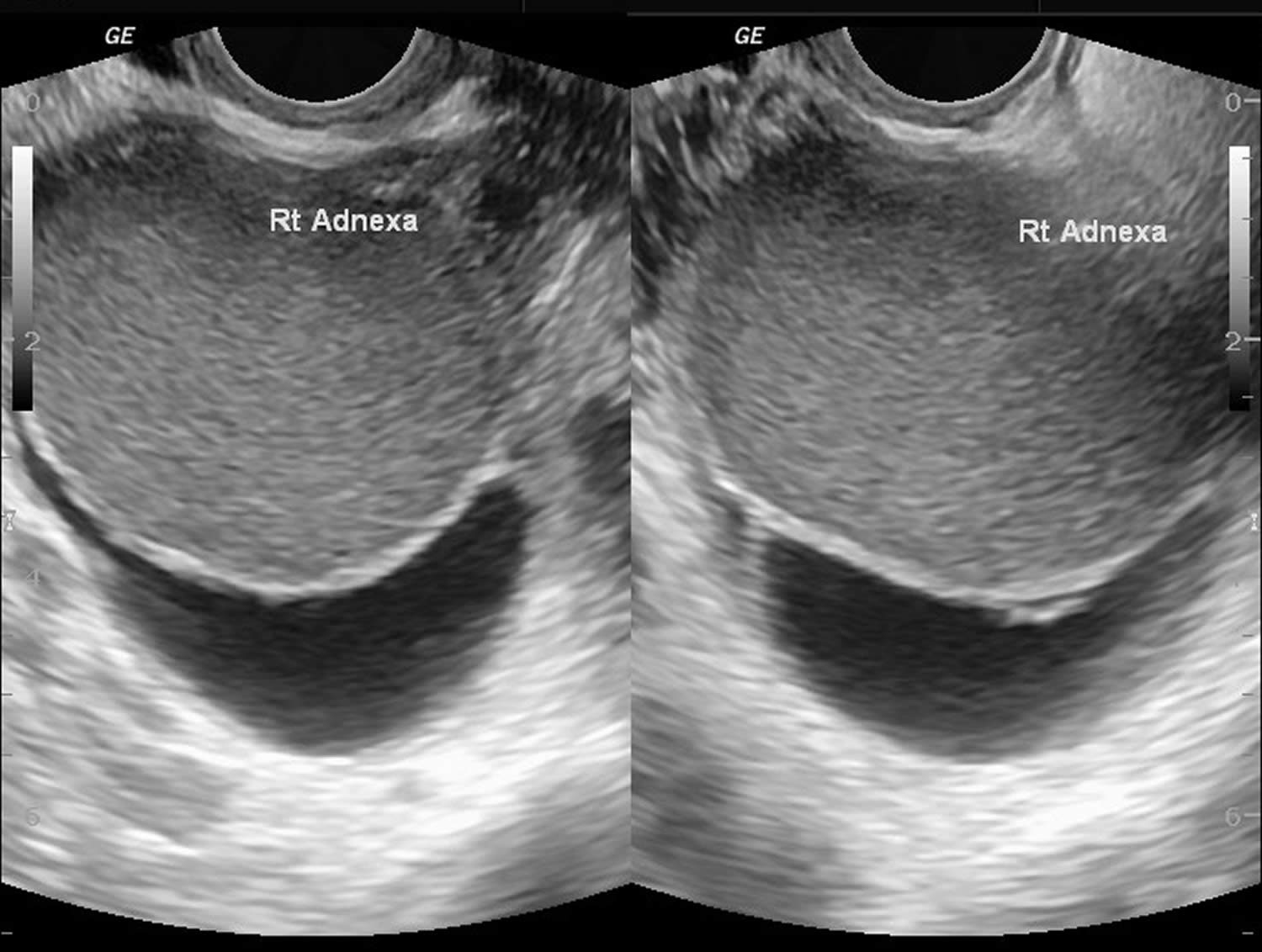

If you have symptoms of ovarian cysts, talk to your doctor. Your doctor may do a pelvic exam to feel for swelling of a cyst on your ovary.

A cyst on your ovary can also be found during a routine pelvic exam. Depending on its size and whether it’s fluid filled, solid or mixed, your doctor likely will recommend tests to determine its type and whether you need treatment.

Tests include:

- Pelvic ultrasound. This test uses sound waves to create images of the body. With ultrasound, your doctor can see the cyst’s: Shape / Size / Location / Mass (whether it is fluid-filled, solid, or mixed). If a cyst is identified during the ultrasound scan, you may need to have this monitored with a repeat ultrasound scan in a few weeks, or your doctor may refer you to a doctor who specializes in female reproductive health (obstetrician–gynecologist).

- Pregnancy test to rule out pregnancy. A positive test might suggest that you have a corpus luteum cyst.

- Hormone level tests to see if there are hormone-related problems

- Tumor marker tests. If you are past menopause, your doctor may give you a test to measure the amount of cancer-antigen 125 (CA-125) in your blood. The amount of CA-125 is higher with ovarian cancer. If your ovarian cyst is partially solid and you’re at high risk of ovarian cancer, your doctor might order this test. In premenopausal women, many other illnesses or diseases besides cancer can cause higher levels of CA-125. Elevated CA 125 levels can also occur in noncancerous conditions, such as endometriosis, uterine fibroids and pelvic inflammatory disease (PID).

- Laparoscopy. Using a laparoscope — a slim, lighted instrument inserted into your abdomen through a small incision — your doctor can see your ovaries and remove the ovarian cyst. This is a surgical procedure that requires anesthesia.

Sometimes, less common types of cysts develop that a health care provider finds during a pelvic exam. Solid ovarian cysts that develop after menopause might be cancerous (malignant). That’s why it’s important to have regular pelvic exams.

It is almost never appropriate to aspirate an ovarian cyst for diagnostic purposes. False negative results are common and leakage of cyst contents into the peritoneal cavity potentially increases the stage of any cancer found, decreasing patient survival.

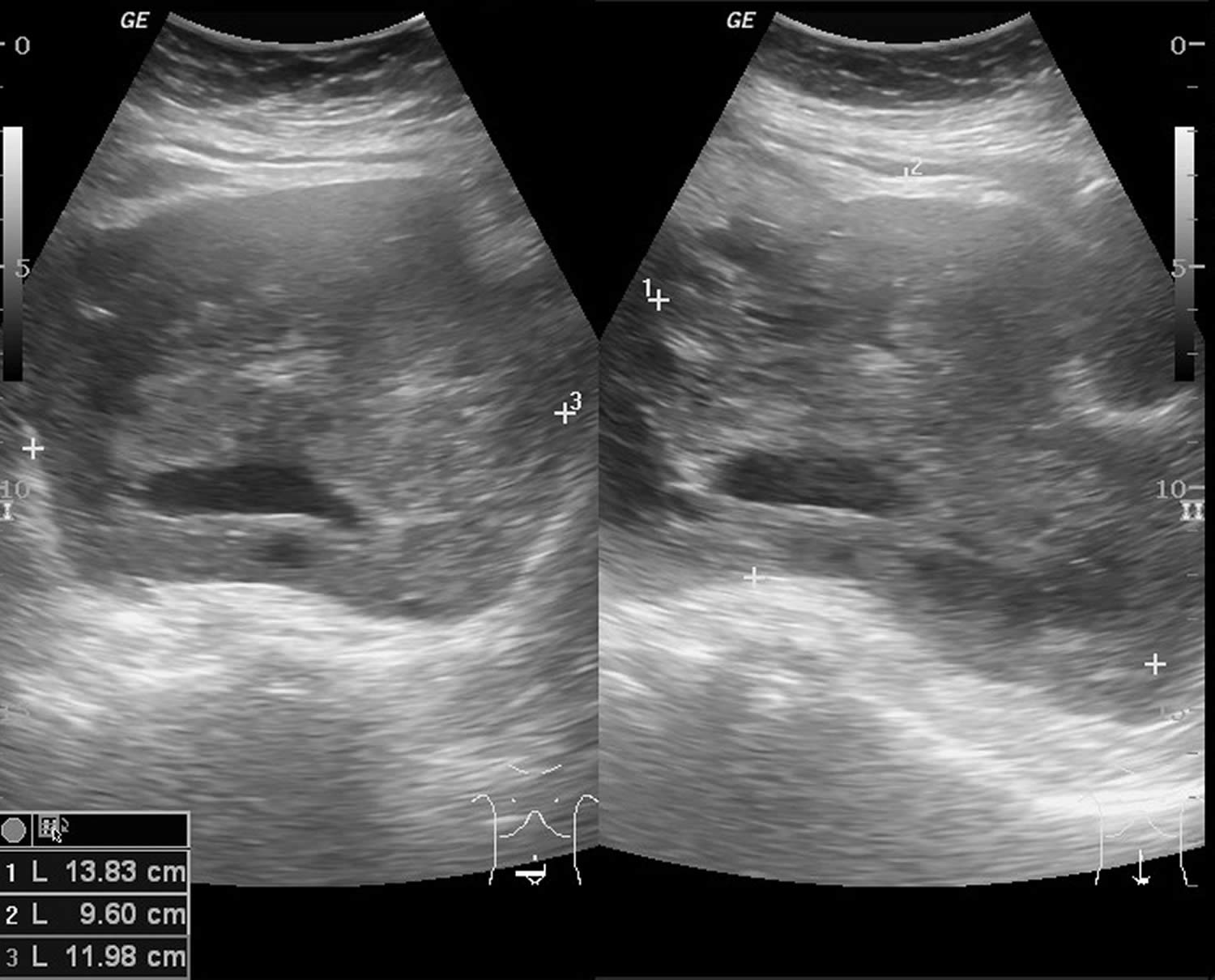

Ovarian cyst ultrasound